“They taught us to arrest in order to investigate, not to investigate in order to arrest.”

—Interview with a police officer, Mexico CityIntroduction

What restrains police brutality—illegal arrests, coercion of witnesses, fabrication of evidence, and the use of torture to extract confessions? This question is closely related to a classic puzzle in political science: the origin and maintenance of constraints on the state’s exercise of coercive power. As police forces are the institution through which modern states enforce laws in their territories and their repressive capacity constitutes a threat to the livelihoods of civilians, police ought to use force while adhering to the rule of law. These limits are essential to prevent state agents from using their coercive powers to subjugate and oppress. Pinker (Reference Pinker2011) argues that the abolition of inhumane criminal punishments and torture to extract confessions is evidence of humankind’s progress toward a more enlightened, humane, and peaceful order. Yet we know little about how societies achieve this transition in the first place.

Theoretical explanations for the consolidation of a range of related phenomena—from individual rights to democratic transitions to constraints on the state—tend to focus on the actions of elites, the middle class, or the median voter (Ansell and Samuels Reference Ansell and Samuels2010; Boix Reference Boix2003; North and Weingast Reference North and Weingast1989; Weingast Reference Weingast1997). Here, we examine a case of constraints on state transgressions committed by law enforcement agents against accused criminals, a group that typically lacks the political clout to produce changes in the social contract. A large body of work argues that democratic institutions reduce the incidence of torture. Political participation, electoral contestation, and freedom of expression can correct the excesses of state coercion (Cingranelli and Richards Reference Cingranelli and Richards1999; Conrad and Moore Reference Conrad and Moore2010; Davenport Reference Davenport1996; Davenport Reference Davenport1999). Moreover, democracies have more veto players and real judicial independence that enhance human rights protections (Conrad and Moore Reference Conrad and Moore2010; Michel and Sikkink Reference Michel and Sikkink2013; Powell and Staton Reference Powell and Staton2009). But, as this paper demonstrates, the use of torture in criminal prosecutions can be a generalized practice even in democratic societies.

The scholarly literature on Latin American democratic institutions has paid close attention to the evolution of judicial powers and independence as well as the role of courts in an institutional architecture that balances against other branches of government (Domingo Reference Domingo2000; Helmke Reference Helmke2002; Helmke and Ríos-Figueroa Reference Helmke and Ríos-Figueroa2011; Kapiszewski and Taylor Reference Kapiszewski and Taylor2008; Navia and Ríos-Figueroa Reference Navia and Ríos-Figueroa2005; Ríos-Figueroa Reference Ríos-Figueroa2007; Sánchez, Magaloni, and Magar Reference Sánchez, Magaloni, Magar, Helmke and Ríos-Figueroa2011). A related strand of research explores the economic role of courts in protecting property rights (Acemoglu and Johnson Reference Acemoglu and Johnson2005; La Porta et al. Reference La Porta, Lopez de Silanes, Pop-Eleches and Shleifer2004). Less examined, however, is how the judiciary and the body of criminal law operate in concert to constrain the individual agents operating on behalf of the coercive apparatus of the state.

Without limits on the actions of police forces, there can be no democratic citizenship. O’Donnell (Reference O’Donnell1993) captures the failure of universalistic democratic citizenship with his metaphor of “brown areas.” Among scholars focusing on Latin America, Brinks (Reference Brinks2007) was among the first to bring this concept to life with his analysis of the Brazilian and Argentine justice systems’ failures to punish large numbers of police homicides. Other scholars have also emphasized how the legacy of authoritarianism and military control over the criminal justice system represent critical obstacles for democracy and police reform (Cruz Reference Cruz2011; Shirk and Cázares Reference Shirk, Cázares, Cornelius and Shirk2007; Uildriks Reference Uildriks2010; Ungar Reference Ungar2002). Although there have been many attempts to modernize police forces throughout Latin America (Bailey and Dammert Reference Bailey and Dammert2005; Davis Reference Davis2006; Uildriks Reference Uildriks2009), there remains persistent skepticism about whether these reforms have worked. In one of the most comprehensive treatments of police forces in Latin America, González (Reference González2019) argues that undemocratic coercive police institutions persisted well after dictatorships ended and that meaningful police reforms only happen sporadically (i.e., when societal preferences converge and there is robust political opposition). In short, the link between democracy and limits on coercive institutions is, at best, unclear.

This paper explores the obstacles democratic states face in their attempts to restrain one of the most insidious forms of police brutality: torture. We highlight two main factors that allow this ruthless policing practice to persist under democracy. First, we emphasize the role of inquisitorial criminal justice institutions, which Latin American states have retained since colonial times. Few countries reformed these institutions at the time of their transitions to democracy, and others have yet to abandon them. Because of their strong reliance on confessions, the absence of an independent judge to control the phase of investigation and counteract potential biases, and lax standards of due process, inquisitorial criminal justice systems expand opportunities for the police to torture.

A second reason why democratic states might fail to restrain their coercive apparatus relates to the persistence of violent challenges to the state. Transitions to democracy in Latin America coincided with a dramatic increase in crime and insecurity. The region is today the most violent in the world outside of war zones. These high levels of insecurity have often pushed governments to adopt mano dura security strategies, including police militarization and the deployment of the armed forces (Bailey and Dammert Reference Bailey and Dammert2005; Flores-Macías and Zarkin Reference Flores-Macías and Zarkin2019). These security policies have introduced elements of authoritarianism into democracy, subsequently bringing about denials of due process and violations of human rights (Godoy Reference Godoy2006). This part of our argument is consistent with a strand in the human rights literature that argues that democracies generally torture less, but their “good behavior” disappears when they face violent dissent (Davenport and Armstrong Reference Davenport and Armstrong2004). This line of work aims to make sense of why democratic states engage in torture against rebels or terrorists, as in the cases of torture perpetrated by U.S. soldiers at Abu Ghraib in Iraq and Guantánamo Bay (Danner and Fay Reference Danner and Fay2004; Davenport, Moore, and Armstrong Reference Davenport, Moore and Armstrong2007; Greenberg Reference Greenberg2005). When there is a violent threat, the electoral incentives that otherwise restrain officials from resorting to torture might loosen. Following Walzer (Reference Walzer2004), the people are unlikely to hold the executive accountable for “dirtying his hands” with torture if they believe it was conducted to keep them safe. Our paper expands upon this line of argumentation by considering threats to the state by criminal groups. In contrast to the torture democracies use against terrorists that is mostly sporadic and targeted, the form of torture this paper studies is generalized.

To understand the challenges democratic societies face in restraining institutionalized brutality, this paper focuses on Mexico, where prosecutors and police continued to use torture as their modus operandi in criminal prosecution years after the democratic transition, which took place in 2000 when the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) lost power for the first time in over six decades of uninterrupted rule (Langston Reference Langston2017; Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006). During the autocratic period, courts gave confessions full probative value regardless of how they were obtained: it did not matter whether there were indications that the detainee had been beaten, suffocated, electrocuted, subjected to prolonged detention, or denied access to a lawyer. With no capacity to investigate, overworked prosecutors and police officers have traditionally relied on coerced confessions and the intimidation of witnesses as an attractive method to close cases. Moreover, in 2006, the federal government declared a war against drug trafficking syndicates and deployed thousands of soldiers to assist local police forces in fighting organized criminal groups (hereafter OCGs). This paper provides compelling empirical evidence that these security interventions substantially increased torture.

In 2008, the Mexican Congress approved a major criminal justice reform to abandon the inquisitorial criminal justice system. This reform included stronger protections for the rights of suspects and significant judicial oversight over police and prosecutors in the pretrial phase, all of which in theory should constrain torture. The reform was adopted at a time when the federal government had just declared the Drug War. Due to the lack of presidential commitment and the magnitude of the changes required, it would not be implemented until the following administration. This paper leverages the staggered implementation of the reform in nearly 300 judicial districts to causally identify its effects on torture. While our focus is Mexico, this institutional change is part of a broader regional trend of reforms that took place in fifteen Latin American democracies during the last two decades (Hammergren Reference Hammergren2008; Rodrigo de la Barra Cousino Reference Rodrigo de la Barra Cousino1998; Shirk Reference Shirk2010). These criminal justice reforms are, according to Langer (Reference Langer2007), the deepest transformations that Latin American criminal procedures have undergone in nearly two centuries. Although the scholarly literature agrees about the relevance of these reforms, the fundamental question that remains unanswered is whether they work to restrain police brutality.

Empirically, our data comes from the National Survey of the Population Deprived of Liberty (ENPOL) conducted by the Mexican National Statistics Agency (INEGI) in 2016. This survey draws on the responses of a representative sample of 58,127 prisoners to 10 questionnaires covering their backgrounds, experiences with the criminal justice system, and lives in prison. The ENPOL includes an extensive battery of questions, including questions on physical abuse, about how the police and agents of the public prosecutorFootnote 1 treated the prisoner at the time of his or her arrest.

To causally identify how militarized security interventions and criminal justice reform impact torture, our statistical analyses leverage the timing of implementation of “joint operations,” on one hand, and the implementation of the reform, on the other. We consider any individual as “treated” by this security intervention if he was arrested in a state at the time when militarized interventions took place.

Similarly, any individual arrested in a municipality after the new code of criminal procedure took effect is treated by the reform. As this reform was implemented on 65 different dates from 2014 to June 2016, it is unlikely that our findings reflect changes in conditions beyond the criminal justice reform. By including geographic and time fixed effects as well as individual controls, our empirical strategy controls for unobserved characteristics in all treated units that are constant over time, observed individual characteristics, and major events.

Our results compellingly demonstrate that militarized security interventions produce sharp increases in torture and other forms of police brutality. The effects are substantial—in the range of 5 to 10 percentage points—depending on the coercive institution performing the arrest. Moreover, our results also demonstrate that the criminal justice reform significantly restrains these abuses. Depending on the model used and the coercive institution carrying out the arrest, the effects of the criminal justice reform are of a similar magnitude. In relative terms, the models show these are declines of up to 23% from baseline levels of abuse. Lastly, we demonstrate that the justice reform restrained abuses but less so when prisoners are accused of crimes the law classifies as part of the category of “organized crime.” In these cases, weaker procedural protections and the greater likelihood of military involvement open the door to the persistence of torture and abuse.

Inquisitorial Criminal Justice in Latin America

In most ancient, medieval, and early modern societies, judicial torture was legal and formally regulated. In the Middle Ages, the torturer was employed by the King or the Inquisition. His function was to obtain confessions from suspects and heretics. Such confessions served as the “queen of evidence” (Regina probationem), which led to the systematic use of torture as a method of prosecution (Peters Reference Peters1996; Ruthven Reference Ruthven1978).

Beginning with England in 1700, most European nations abolished judicial torture by 1850 (Pinker Reference Pinker2011). Criminal justice was imbued with rationalistic ideas, including that torturing people to extract confessions was an ineffective method of discovering the truth. Instead, the notion that trials should be based on evidence was gradually embraced. Procedural reforms played a critical role to reduce torture in Continental Europe. In 1808, Napoleon introduced his Code d’instruction criminelle, which translated a number of ideas from the English model of criminal procedure to civil law (Langer Reference Langer2007). Its ideas spread across Europe, including Spain. When Latin American countries became independent, they rejected the more liberal European codes and kept the inquisitorial system that had prevailed in the Portuguese and Spanish Americas. The main characteristics of these inquisitorial codes are that the backbone of the criminal process is a written dossier (expediente) that the police and investigating judge compile with all procedural activity; pretrial investigations remain written and secret; the verdict phase is also predominantly written and lacks a jury; and the judge investigates, prosecutes, and adjudicates (Langer Reference Langer2007).

Because of their strong reliance on confessions and weak procedural standards, inquisitorial criminal justice systems expand opportunities for the police to torture. In their empirical cross-sectional study of torture, Conrad and Moore (Reference Conrad and Moore2010) use a dummy variable for civil law countries as a proxy for inquisitorial criminal justice procedures and find that this increases torture. The problem with their approach is that, as the case of Latin America makes explicit, many civil law countries have actually abandoned the inquisitorial model. Hence, to our knowledge, there is no systematic empirical evidence that the inquisitorial model is associated with more torture.

During the last two decades, a major institutional transformation took place as many Latin American countries reformed their inquisitorial criminal justice procedures. The dates of these implementations were as follows: Argentina (1991), Guatemala (1994), El Salvador (1998), Costa Rica (1998), Venezuela (1999), Chile (2000), Paraguay (2000), Ecuador (2001), Bolivia (2001), Honduras (2002), Nicaragua (2001), Dominican Republic (2004), Colombia (2005), Peru (2006), and Mexico (2008) (Biebesheimer and Payne Reference Biebesheimer and Mark Payne2001; Langer Reference Langer2007; Rodrigo de la Barra Cousino Reference Rodrigo de la Barra Cousino1998; Ungar Reference Ungar2002). With a few exceptions, in most of these cases, reforms were adopted years after democratic transitions, which means that democracy in most cases was born with limited human rights protections. Although the new criminal justice procedures implemented in the region vary, most provide for an oral hearing and an adversarial process. Additionally, these new procedures expand judicial oversight over the investigation, institute legal checks on police actions, and add more procedural protections for defendants.

Despite the importance of the reforms, there are basically no empirical investigations about their impact. To our knowledge, the only exception is Kronick and Hausman (Reference Kronick and Hausman2019), who demonstrate that the reforms reduced the number of arrests in Columbia and Venezuela and increased extrajudicial killings in the latter case. Here, we explore how the reforms shaped torture in criminal prosecution in Mexico, the country that has taken longest to adopt them.

The Case of Mexico

The scholarly literature argues that autocrats use repression, including torture, to extract information about potential conspiracies, to dissuade opponents, and to punish acts of dissent (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2018; Davenport and Inman Reference Davenport and Inman2012; Svolik Reference Svolik2012; Wantchekon and Healy Reference Wantchekon and Healy1999). Our paper examines a case of widespread torture that the police and public prosecutors would use in common criminal trials. This does not deny that Mexico’s autocratic regime resorted to torture to repress political dissidents. For example, there is ample evidence that during the Dirty War (1965–1982), torture was used as a way of pursuing political enemies (Aviña Reference Aviña, Herrera and Cedillo2012; Castellanos Reference Castellanos2007; González Villarreal Reference Villarreal and Roberto2014). But torture was not always mandated by the top political leadership. It emerged as the modus operandi in criminal prosecution as coercive institutions liberally used it to extract confessions in criminal trials.

During the autocratic period, courts gave confessions full evidentiary value regardless of how they were obtained or whether the suspect had been given access to a lawyer. Magaloni, Magaloni, and Razu (Reference Magaloni, Magaloni and Razu2018) cite several jurisprudential theses that illustrate this problem. The Supreme Court in this period allowed as admissible confessions even if there was evidence of physical mistreatment or prolonged detention, ignored protests about denials of access to counsel, and placed high probative value on confessions made to the police even if the defendant tried to recant his statements before a judge. In short, the judiciary created a permission structure for police to violate fundamental rights in the administration of justice. Naturally, prosecutors and police came to see coerced confessions, the intimidation of witnesses, and the fabrication of evidence as attractive options for closing cases.

The Militarization of Security

The criminal justice system that democratic Mexico inherited was unprepared to face rising levels of insecurity. Alternation of political power at a local level in the 1990s and when the National Action Party (PAN) won the presidency in 2000 broke down the old ways of negotiating with criminal groups that had previously maintained order (Astorga Reference Astorga2003; Dube, Dube, and García-Ponce Reference Dube, Dube and García-Ponce2013; Osorio Reference Osorio2015; Ríos Reference Ríos2013; Trejo and Ley Reference Trejo and Ley2018;Watt and Zepeda Reference Watt and Zepeda2012). At the same time, crackdowns in Colombia and the Caribbean made drug syndicates shift operations to Mexico (Castillo, Mejía, and Restrepo Reference Castillo, Mejía and Restrepo2020).

In 2006, President Felipe Calderón (PAN) responded to these security challenges by declaring a war against drug syndicates. During this war, the armed forces operated extra-judicially, using killings, arbitrary detention, and disappearances (Anaya Reference Anaya2014; Gonzalbo Reference Gonzalbo2011; Silva Forné, Pérez Correa, and Gutiérrez Rivas Reference Silva Forné, Correa and Rivas2012; Reference Silva Forné, Pérez Correa and Gutiérrez Rivas2017). Magaloni, Magaloni, and Razu (Reference Magaloni, Magaloni and Razu2018) present empirical evidence that the Drug War sharply increased torture in two scenarios: (a) when the armed forces detained a suspect and (b) when suspects were accused of drug trafficking.

Our theoretical approach proposes that militarized security interventions should increase torture by regular police forces as well. The government carried out militarized interventions known as “joint operations” through which the armed forces and federal police were deployed to assist local police forces in fighting organized crime. These security operations, we propose, introduced into law enforcement a combination of equipment, tactics, and culture that centers on violent conflict, a phenomenon commonly referred to as “militarization of policing” (Mummolo Reference Mummolo2018a). Alongside the use of these tactics and equipment comes a military mindset wherein the police treat suspected criminals as though they were enemies of the state, acting as though their job was to occupy a war zone. This process of police militarization is likely to increase the use of extrajudicial force and torture. We test the following hypothesis:

H1:Militarized security interventions known as “joint operations” should result in significant increases in torture, and this increase should not be driven solely by the military.

The 2008 Criminal Justice Reform

In the midst of this violence, the Mexican Congress passed a major reform in 2008 that transformed the inquisitorial criminal system. In response to the aforementioned problems of the use of torture to extract confessions, the reforms make it unlawful to present confessions as evidence in court unless they are obtained in the presence of the suspect’s defense attorney (Shirk Reference Shirk2010). The prosecution of a crime is now handled by a panel of three judges. The controlling judge (juez de control) has the obligation to evaluate the legality of the detention, order the release of individuals whose detention was not carried out in a manner adhering to the provisions of the law, and exclude illegally obtained evidence. The trial itself has the second judge presiding through the sentencing of the defendant. Throughout this judicial process, there are provisions that restrict evidence obtained by violations of due process rights from entering the record. Finally, the third judge oversees the execution of the sentence. The reform further added procedural protections for defendants and instituted oral trials, thus allowing far greater opportunity for the defendant to challenge the prosecution’s evidence. Another important change is the emphasis on the physical presence of judges during all hearings involving the defendant.

The reform would have failed to progress had it not been for substantial opposition to the Calderón administration’s security policies within Congress. The bill that became the basis for the 2008 reforms was championed by the head of the Judicial Committee in the Chamber of Deputies, a member of the PRI (Shirk Reference Shirk2010). This party saw in the criminal justice reform a way to impose stronger oversight over president Calderón’s security policies. Under supporting legislation for these reforms, a new Federal Police would be created in 2009. Although the new Federal Police would have greater power to conduct intelligence and undercover operations, the reform would ensure more checks on their actions.

Additionally, as in other countries across the region, international factors played a role in driving the reforms (Domingo Reference Domingo, Schedler, Diamond and Plattner1999; Reference Domingo2000; Hammergren Reference Hammergren, Jensen and Heller2003; Langer Reference Langer2007). The Calderón government faced significant accusations of human rights violations from international organizations. Moreover, within the new architecture for bilateral security cooperation between the United States and Mexico—the Mérida Initiative—Mexico would receive billions of dollars from the US to fight drug syndicates. Although these funds would mostly be allocated to equipment and training to enhance military and police capacity, Mexico had to commit to enhance the rule of law to get US financial and technical support. After the criminal justice reform was approved, significant resources from the Mérida initiative would go to facilitate Mexico’s transition to the new criminal justice system.Footnote 2 Lastly, during the Calderón administration, civil society in Mexico began to mobilize against public insecurity, forced disappearances, and corruption in the criminal justice system (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2017). Although these protests were mostly against public insecurity, they would bolster support for deeper criminal justice reforms pushed by a small group of activists, human rights groups, and jurists organized around issues of due process, extrajudicial killings, and torture.Footnote 3

The reform effort did not begin to proceed seriously until the Peña Nieto administration, when the new government began doubling its spending on federal grants to states to assist with implementing the reform (Rodríguez Ferreira and Shirk Reference Rodríguez Ferreira and Shirk2015). In 2014, the federal government passed the National Code of Criminal Procedure, which all states were obligated to adopt and is the treatment we examine in this paper.

Judicial Checks on Prosecutions

Our theoretical discussion highlights judicial checks on prosecutors and police as one of the main reasons why the criminal justice reforms restrain torture. The reform introduced new protections like the explicit prohibition of torture and the fact that confessions are inadmissible in court unless they are extracted in the presence of a defense attorney. To be effective, these legal prohibitions require judicial willingness to enforce them. Thanks to the criminal justice reform, for the first time the Mexican judiciary would have an explicit constitutional mandate to impose checks on prosecutors and police. A critical question is the extent to which courts actually have begun to impose these controls.

In order to shed light on this mechanism, we use a structural topic model trained on a corpus of 2,078 Mexican jurisprudential theses. A topic model presents text generation as a hierarchical model in which an author draws a topic at random, then draws a word at random from a distribution over words that is specific to that topic; the model infers topics in a document conditional on the distribution of words in that document and the co-occurrence of words across documents (Blei Reference Blei2012; Blei, Ng, and Jordan Reference Blei, Ng and Jordan2003). Here, we present results from a model with five topics.Footnote 4 The texts were scraped from the website of the Mexican Supreme Court covering the period from 1988Footnote 5 to early 2019 and are those that were classified by the Court as relating to criminal law. Decisions were classified based on whether a given topic was a plurality of the estimates for the thesis. We then plot the proportions of each year’s decisions classified under each topic against the year the decision was published in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Jurisprudential Theses on Criminal Law, 1988–2019

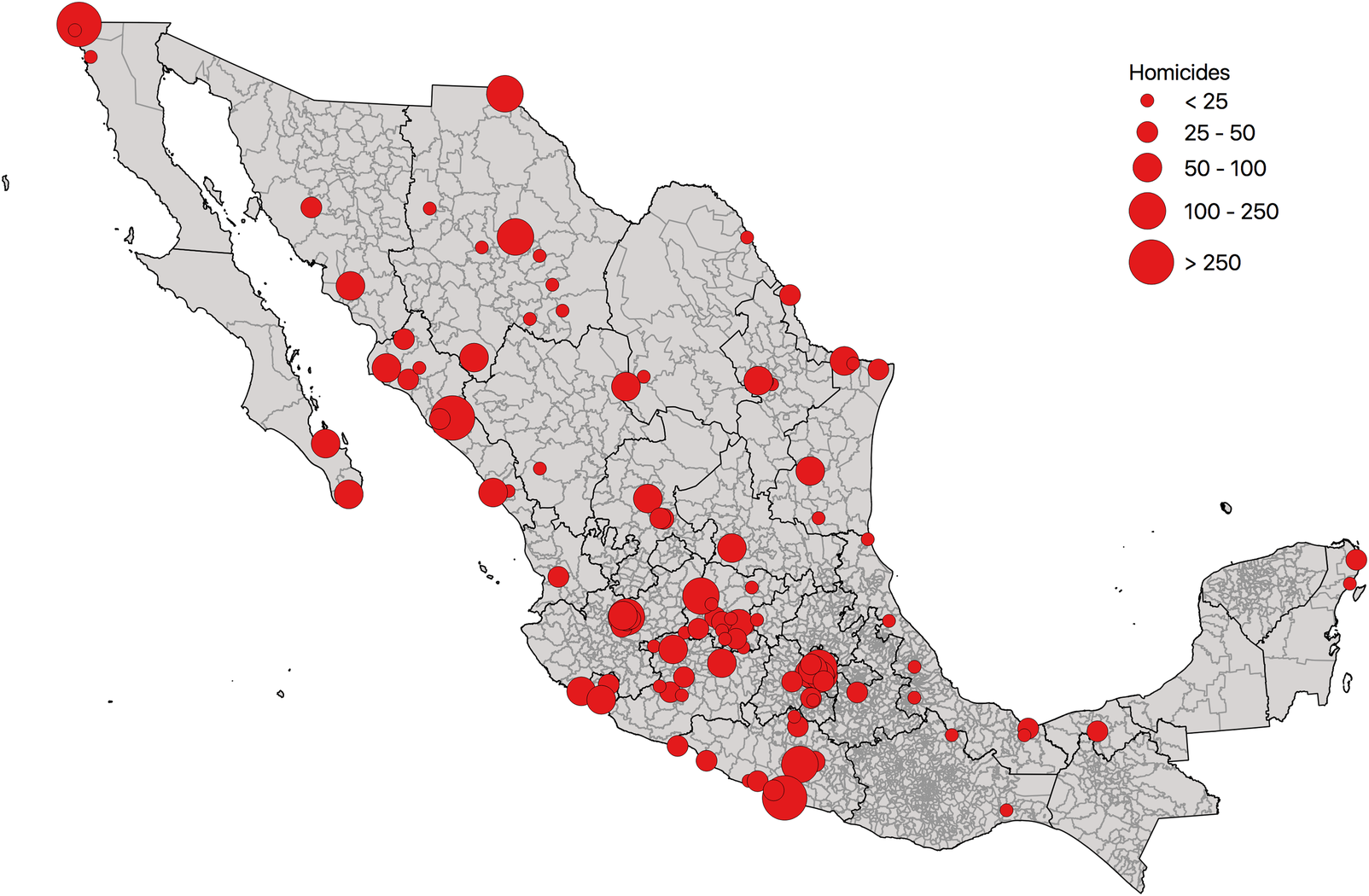

Figure 2. Turf Wars from 2013 to 2018

Topic 4Footnote 6 in this model is closely tied to concerns about basic human and procedural rights, international law, and torture. This topic begins as the least common class of decisions in 1990 and then starts steadily increasing around 2008 when the reform process began. We note that although the reform was not implemented in the states until after 2014, the corpus of law was incorporated into the constitution in 2008, which opened the door for the Supreme Court to begin to interpret it.

Technically, most cases involving violations of due process rights and allegations of torture arrive in federal courts through Amparo trials (a form of habeas corpus). By raising constitutionality issues, cases could reach the Supreme Court even before the implementation of the reform at the local level. After implementation, it stands to reason that more cases related to violations of due process would begin to be heard before lower level courts, whose decisions can be challenged in Collegiate Tribunals. The Supreme Court has a right to take these cases. It goes beyond the scope of this paper to document how lower level courts are enforcing the new legal corpus, but we believe that variation across states in judicial capacityFootnote 7 and willingness to enforce the legal corpus might help explain why the reform is more effective in some states than others. We leave this question for further research.

To illustrate the importance of judicial checks for restraining torture, we discuss two highly visible rulings. The first involves a 2013 decision to release twelve people serving prison terms for a 1997 massacre in the community of Acteal, Chiapas, in which 45 victims were killed. The Court argued that the evidence presented by the Attorney General’s Office was illicit because he used “forged evidence and coerced testimonies”—the main evidence presented against the accused and by which they were all convicted. Another historic decision came in 2018 from the First Collegiate Tribunal of the 19th Circuit against the Attorney General’s Office for its illicit investigative tactics regarding the disappearance in 2014 of 43 students from the rural college of Ayotzinapa. The Tribunal upheld the decision of a lower-level court that ruled in favor of four imprisoned witnesses who said they were tortured by the authorities as part of the federal investigation. Moreover, the tribunal condemned the Attorney General for having used torture as one of the components of a fabricated case.

Exploratory interviews we collected with police officers in Guadalajara, Monterrey, and Mexico City between the fall of 2017 and first six months of 2018, which we discuss in Section 8 of the Online Appendix, reveal that the expectation that judges will release suspects if police violate due process is a major force driving changes in police behavior, also contributing to change in the way police corporations reward officers. Monetary bonuses for the number of arrests or “solved murders per month,” which have been common practices, generate incentives for police to torture and, as some of our interviewees revealed to us, these incentives are “no longer compatible with the criminal justice system.”

Implementation of the Reform

The staggered implementation of the reform is outlined in Table 1. The dates are the unique dates on which the reform was implemented within that state. States with only one date imply that the reform was implemented across the state all at once, while those with multiple dates imply staggered implementation across judicial districts.

Table 1. Reform Implementation Dates Examined

Note: States with only one date imply that the reform was implemented across the state all at once, while those with multiple dates imply staggered implementation across judicial districts. Asterisks refer to states that implemented the reform by category of crime.

There were three ways by which states updated their systems. States (a) created a timetable whereby the reform would take effect in specific geographic units (judicial districts or the entire state) on a certain date, (b) created a timetable whereby the reform would begin covering certain classes of crimes on a given date, or (c) chose some combination of the two. Asterisks indicate jurisdictions that implemented the reform following methods (b) or (c). We obtained the dates of implementation by state through the Supreme Court’s website and state records.

As noted by Shirk (Reference Shirk2010), the scope and scale of change contemplated under the 2008 judicial reforms were enormous. Existing legal codes and procedures needed to be revised both at the federal and state levels; courtrooms needed to be remodeled and outfitted with recording equipment; and judges, court staff, police, and lawyers needed to be retrained to operate under the new system (234). There is likely a great deal of heterogeneity in the way states have adjusted to the reform. On one hand, states might rely more on coerced confessions due to organizational weaknesses and a lack of capacity to investigate crimes, which might partly be driven by absence of adequate personnel, protocols, training, and funding. Institutional corruption might also be driving lack of capacity to investigate crime. In many states, local police are regularly effectively captured by OCGs. Whether they are captured or not might be an important factor in whether they torture and whom they victimize. Moreover, as argued above, local courts’ independence and capacity also matter. Section 4.6 of the Online Appendix presents evidence that bureaucratic and judicial capacities are associated with less torture. In the main body of this paper, we will hold state-level characteristics constant, seeking to identify the causal effects of the abandonment of inquisitorial criminal procedures on torture. We test the following hypothesis:

H2:Torture should decrease with the implementation of the criminal justice reform.

The Reform and “Organized Crime”

Despite the fact that the president approved the reform, it is important to highlight that it was not implemented until after the Calderón presidency was over. Moreover, the reform included loopholes to allow the federal government leeway when prosecuting “organized crime,” which would not fall under many of the protections of the new laws. Organized crime is defined by Federal Law as federal crimes committed by “three or more persons organized permanently or repeatedly” for the purpose of committing serious crimes such as terrorism, drug trafficking, counterfeiting, arms trafficking, human trafficking, organ trafficking, kidnapping, and car theft. In cases involving organized crime, the reform entailed a constitutional amendment to allow for the sequestering of suspects under arraigo (extended pretrial detention) for up to 40 days without criminal charges (with a possible extension of an additional 40 days). Many of these crimes correspond to the federal jurisdiction and hence the loopholes in the law affect more federal prisoners. Prisoners may be held in solitary confinement and placed in special detention centers created explicitly for this purpose.

Given these legal exceptions with respect to organized crime and also in line with the existing literature on “violent dissent” (Davenport, Moore, and Armstrong Reference Davenport, Moore and Armstrong2007), our theoretical approach proposes that high levels of organized criminal threat should increase torture and other forms of police brutality. We test the following hypotheses:

H3:Torture should be likelier when the threat of organized crime is high.

H4:Organized crime threats should mitigate the effects of the reform restraining torture.

H5:Federal prisoners should be subject to more abuse than state prisoners.

H6:The criminal justice reform should constrain abuses against suspects accused of common crimes, but still grant leeway to commit abuses against criminal suspects accused of “organized crime.”

To measure organized crime threats, we focus on turf wars. Existing literature agrees that militarized security policies and the arrest of drug kingpins spread violence (Calderón et al. Reference Calderón, Robles, Díaz-Cayeros and Magaloni2015; Dell Reference Dell2015; Lessing Reference Lessing2015). Turf wars erupted between drug trafficking organizations fighting for control of the most valuable drug trafficking corridors and border cities to smuggle drugs to the US. At the same time, the arrest of drug kingpins had the effect of fragmenting criminal organizations and breaking up chains of command. Drug syndicates began to diversify their portfolio into extortion and other crimes, including human trafficking. To identify turf wars, we focus on extraordinary increases in violence, defined as periods when homicide rates in a municipality increase by more than three standard deviations relative to the municipality’s historic mean. Figure 2 displays the municipalities where there was a turf war during the period of implementation of the reform.

Data

Our data come from the National Survey of the Population Deprived of Liberty (ENPOL), conducted by INEGI. The survey contains 10 questionnaires covering the backgrounds of incarcerated individuals, their experience of the criminal justice system, and their lives in prison. We distinguish between two different kinds of torture derived from the ENPOL. First, we examine what we call “brute force.” To construct our measure of brute force, we use two questions: (a) whether the individual was beaten or kicked and (b) whether the individual was beaten with objects. Responding affirmatively to one of the questions constitutes brute force torture.Footnote 8 We contrast this with what we term institutionalized torture. Following Magaloni, Magaloni, and Razu (Reference Magaloni, Magaloni and Razu2018), we take this as torture that requires a dedicated space, equipment, or training to be carried out effectively. Since this kind of torture requires physical and human resources in the form of space, specialized equipment, and some degree of training to avoid killing the victim,Footnote 9 we believe that it requires some level of institutional endorsement and support to take place, either in the cells of police stations, the prosecutor’s headquarters, or a clandestine detention center. We operationalize this concept by using questions about whether a respondent was crushed with a heavy object, electrocuted, suffocated or submerged in water, burned, or stabbed while in custody. If the prisoner responds that he was subject to one of these five abuses, he is coded as having been subject to institutionalized torture. Finally, we include reports of threats by authorities either to press false charges or to harm a detainee’s family. We thus have the following measures of violence and intimidation:

1. Brute Force

2. Institutionalized torture

3. Threats.

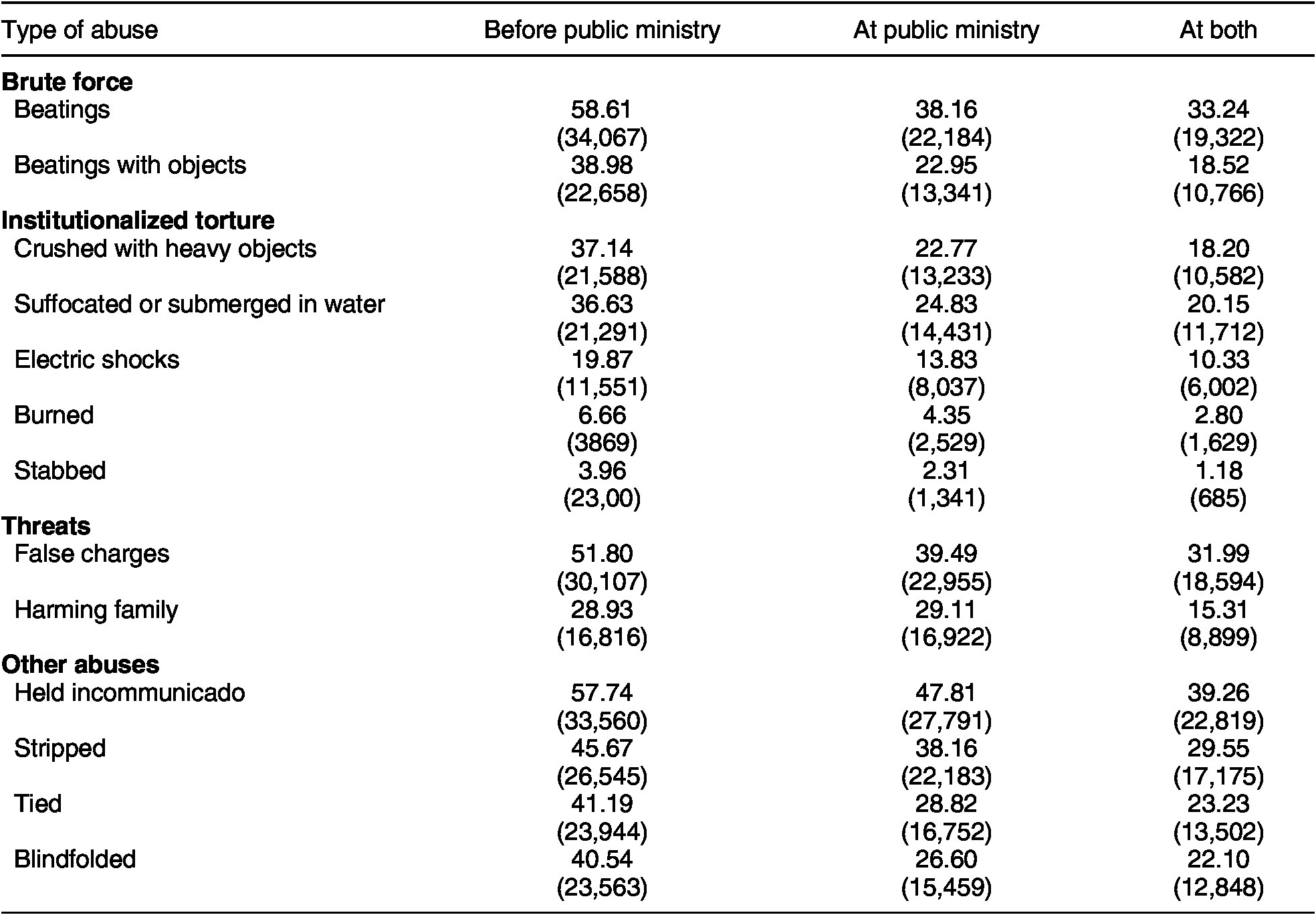

Abuse in the Mexican Criminal Justice System

Table 2 reports the different forms of abuse prisoners experienced. The table distinguishes between reported abuses before the prisoner arrived at the MP and abuses at the MP. It reports the percentage of prisoners experiencing some kind of abuse and the total numbers in parentheses. Notably, violent forms of institutionalized torture are alarmingly common. These forms of institutionalized torture are slightly more common before the suspect arrives at the MP, and they probably take place either in a clandestine detention center or at the police headquarters. Many prisoners report other kinds of abuses, including being held incommunicado, stripped, restrained or tied, or blindfolded. The data also suggest many prisoners are subject to abuses both before and after arriving at the MP.

Table 2. Abuses Reported by Prisoners

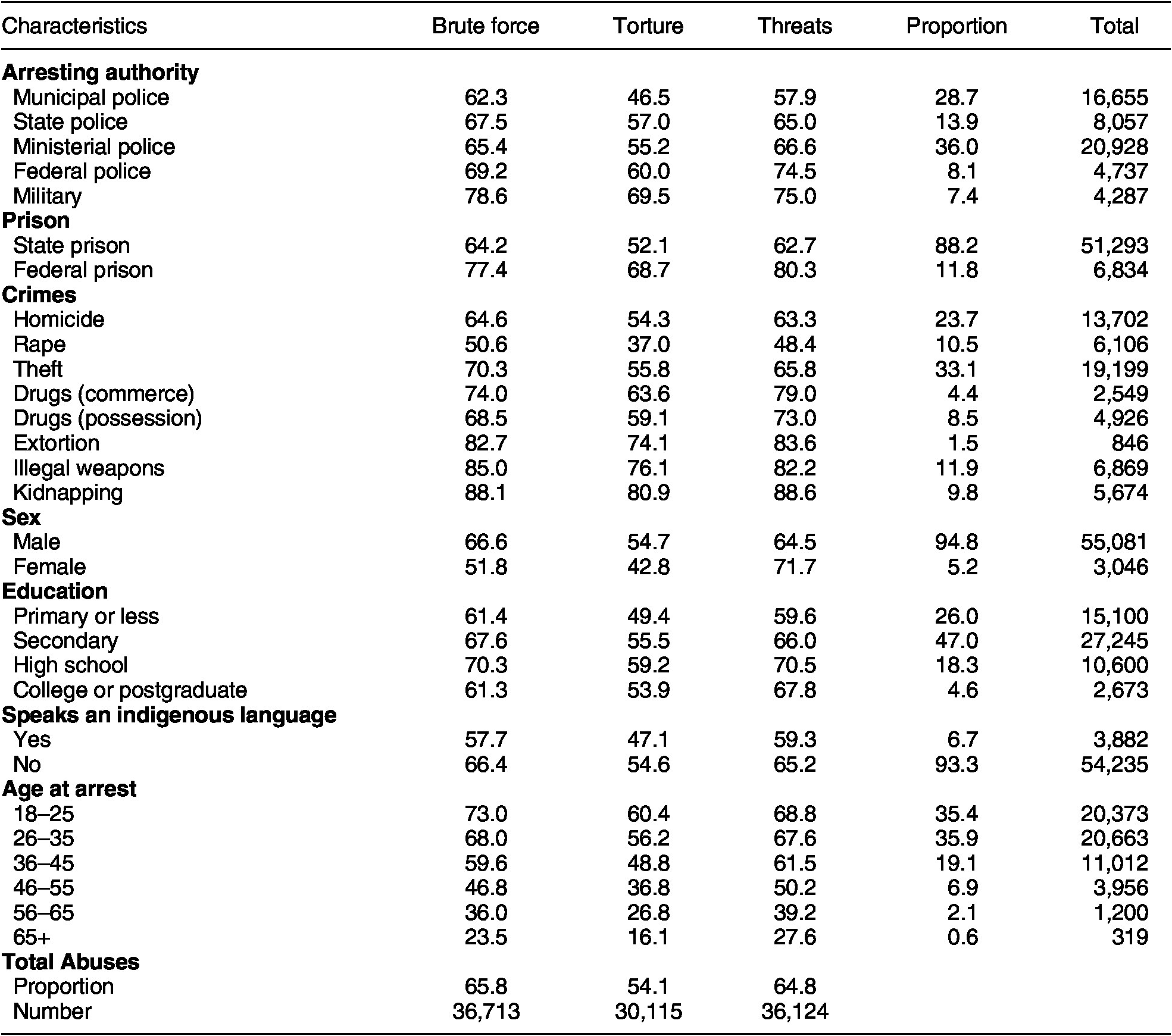

Table 3 classifies abuses into the three categories that will be used for the empirical analyses: brute force, institutionalized torture, and threats. The table also includes basic descriptive statistics that will be relevant for our analysis. The descriptive statistics reveal that abuse is endemic throughout social and demographic subgroups of the data. The data reveal that municipal and ministerial local police forces perform the overwhelming majority of the arrests. As expected, there is a significantly higher incidence of torture for prisoners detained in federal prisons and among those who were detained by the military and federal police. These data reinforce the findings in Magaloni, Magaloni, and Razu (Reference Magaloni, Magaloni and Razu2018), which show that the armed forces are significantly more prone to engage in torture. Although the army, in theory, has better training, better weapons, and may be less corrupt, they deal with more violent threats and engage in more armed combat against OCGs than local police forces do. Moreover, their specialized training, equipment, and culture makes them more prone to use extrajudicial force (Flores-Macías and Zarkin Reference Flores-Macías and Zarkin2019; Pérez Correa, Silva, and Rodrigo Gutiérrez Reference Correa, Catalina and Gutiérrez2015).

Table 3. Covariates of Torture

Note: The rows show the percentage of prisoners in each of the subgroups experiencing abuse. Columns 4–5 report the percentage and total number falling in each category.

Those accused of theft are equally or more likely to be tortured and brutalized than those accused of homicide. These data reveal that the Mexican inquisitorial criminal justice system punished poverty, detaining and torturing thousands of people for petty theft. There is a higher incidence of torture among those accused of kidnapping, possession of illegal weapons, extortion, and drugs commerce. The last rows of the table show that 66% of respondents reported having been subject to brute force, 54% to torture, and 65% to threats.

In terms of how truthful prisoners’ responses might be, it is important to mention that although the majority of respondents had been convicted, those who were in prison waiting for a sentence could have assumed that their answers were consequential for their sentences and might possess more incentives to lie. Table 4 shows the conviction status of the prison population: around 68% had been convicted at the time of the survey, 29% were waiting for a sentence, and 2% were “partially” sentenced. The table also shows the percentage of individuals in each group who reported abuses. Propensities to report abuse are lower among convicted prisoners than among those who had not been convicted, which suggests that the latter group might be giving systematically different responses. The “partially sentenced” group shows a significantly higher propensity to report abuses. We deal with this in the Appendix by matching on sentencing status.

Table 4. Conviction Status and Reported Abuses

Note: Rows 1–3 show reported rates of abuse by conviction status. Row 4 shows total number of prisoners reporting each kind of abuse. Column 4 shows the total number of prisoners in each conviction category.

Trends

Our dependent variables correspond to the three forms of abuse defined above. Each is a binary indicator for whether a respondent reported that kind of abuse. We will use OLS regressions because our models include geographic and time fixed effects, which generate problems in logistic regressions. In Table A3 of the Online Appendix, we present our main models using logits and all of our results hold. To explore time trends, we run the following model:

where ![]() $$ {y}_{ist} $$ is a dichotomous indicator that takes the value of 1 if prisoner

$$ {y}_{ist} $$ is a dichotomous indicator that takes the value of 1 if prisoner ![]() $$ i $$ reports any type of abuse that corresponds to our definition of institutionalized torture, brute force, or threats. The model uses fixed effects for the year and state where the prisoner was detained (

$$ i $$ reports any type of abuse that corresponds to our definition of institutionalized torture, brute force, or threats. The model uses fixed effects for the year and state where the prisoner was detained (![]() $$ {\lambda}_s $$ and

$$ {\lambda}_s $$ and ![]() $$ {\gamma}_t $$, respectively).

$$ {\gamma}_t $$, respectively).

We plot predicted rates of abuses for all prisoners by their year of arrest. As shown in Figure 3, institutionalized torture, brute force, and threats seem to decline gradually until 2006. After that, these abuses increase precipitously until about 2012. These increases coincide with the onset of the Drug War. Abuses then decline with the end of the Calderón presidency. The implementation of criminal justice reform after 2014 appears to accelerate the rate of decline. From these time trends we, of course, cannot infer the causal effects of the Drug War or the reforms. The sections below offer a series of statistical tests to demonstrate causal effects.

Figure 3. Year of Arrest and Types of Abuse

Effects of the Reform

To estimate the effects of the reform, we merged the survey data with the dataset of reform dates described above. To assign prisoners to the treatment, we focus on states that implemented the reform in specific geographic units (judicial districts or the entire state) on a certain date, which are the majority of states.Footnote 10 For states that have multiple implementation dates, each corresponding to defined regions or judicial districts within the state, we examine the municipality where the arrest took place and identify whether that arrest took place before or after the implementation of the reform in that municipality. Any individual arrested on or after the implementation date in a given municipality is considered to have been arrested under the new system.

Table 5 classifies the data in the pre-reform and post-reform periods. The comparison of the entire pre- and post-reform periods shows a dramatic decline in the occurrence of these abuses. Estimating the causal effect of the criminal justice reform on torture is complicated by the fact that unobserved factors may simultaneously lead to the implementation of the reform and affect torture. Our strategy for overcoming this identification challenge relies on a difference-in-difference statistical approach where first, we use judicial district, municipal, or state fixed effects to hold constant time-invariant characteristics of the local police organizations, judges, and authorities. Second, we use fixed effects for the year of the arrest. These are essential to capture national policy effects (e.g., the onset of the Drug War, alternation of political power in office and electoral competition, etc.).

Table 5. Abuses Before and After the Criminal Justice Reform

Note: Percentage of prisoners experiencing each form of abuse in the pre- and post-reform periods. Row 4 indicates the total number of prisoners arrested in each of the periods. The total number of prisoners drops with respect to those reported in Tables 1–3 because we only include prisoners from states that implemented the reform using the geographic criteria.

The model specification is as follows:

where ![]() $$ y $$ is a dichotomous indicator that takes the value of 1 if prisoner

$$ y $$ is a dichotomous indicator that takes the value of 1 if prisoner ![]() $$ i $$ reports any type of abuse that corresponds to our definition of institutionalized torture, brute force, or threats, and

$$ i $$ reports any type of abuse that corresponds to our definition of institutionalized torture, brute force, or threats, and ![]() $$ {T}_i $$ is an indicator variable for treatment. The model also includes

$$ {T}_i $$ is an indicator variable for treatment. The model also includes![]() $$ k $$ individual covariates as well as judicial district and time fixed effects (

$$ k $$ individual covariates as well as judicial district and time fixed effects (![]() $$ {\lambda}_s $$ and

$$ {\lambda}_s $$ and ![]() $$ {\gamma}_t $$, respectively). In terms of individual-level controls, we include age at arrest, gender, education, indigenous language, and income.Footnote 11

$$ {\gamma}_t $$, respectively). In terms of individual-level controls, we include age at arrest, gender, education, indigenous language, and income.Footnote 11

Results of the regression models are provided in Table 6. We find consistent effects of the reform, in the range of 4 to 8 percentage point reductions of different forms of police brutality, depending on type of abuse and model specification. Models 1 to 3 use state fixed effects, models 4 to 6 use judicial district fixed effects, and models 7 to 9 use fixed effects at the municipal level.Footnote 12 In all specifications, we find statistically significant negative effects of the reform.

Table 6. Effects of Criminal Justice Reform: OLS Models

Note: Estimated coefficients for the criminal justice reform from OLS regressions. All models include socioeconomic characteristics and year fixed effects. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered by judicial district. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.10.

In section 4.5 of the Online Appendix, we present evidence of pre-treatment parallel trends. Following Autor (Reference Autor2003) and Angrist and Pischke (Reference Angrist and Pischke2009), we estimate models with monthly leads and lags of the treatment. The models show little evidence of a prior effect, with leads near zero. Additionally, we estimate a stricter model that relaxes the assumption of a common trend by estimating models with unit-specific time trends. These latter models were estimated using state, judicial district, and municipal level time trends. We also estimate this using months, rather than years, as the temporal unit of analysis. We further estimate our main results with state-year fixed effects to avoid assuming linear trends in the data when controlling for changes over time. All 42 models considered in that section of the Online Appendix still pick up the effect of the reform, dramatically bolstering our confidence in our identification strategy.

Confounding Factors

A possible objection to our results is that the decline in torture could result from the fact that, after the reform, police might be arresting fewer criminals for less serious crimes and these persons might be less likely to be tortured. As part of the presumption of innocence, the 2008 reforms seek to limit the use of pretrial detention. Under the new laws, pretrial detention is intended to apply only in cases of violent or serious crimes and for suspects who are considered a flight risk or a danger to society. Although many argue that the law gives too much leeway for interpretation, one of the implications of this law is that we should observe fewer detentions for less serious crimes.

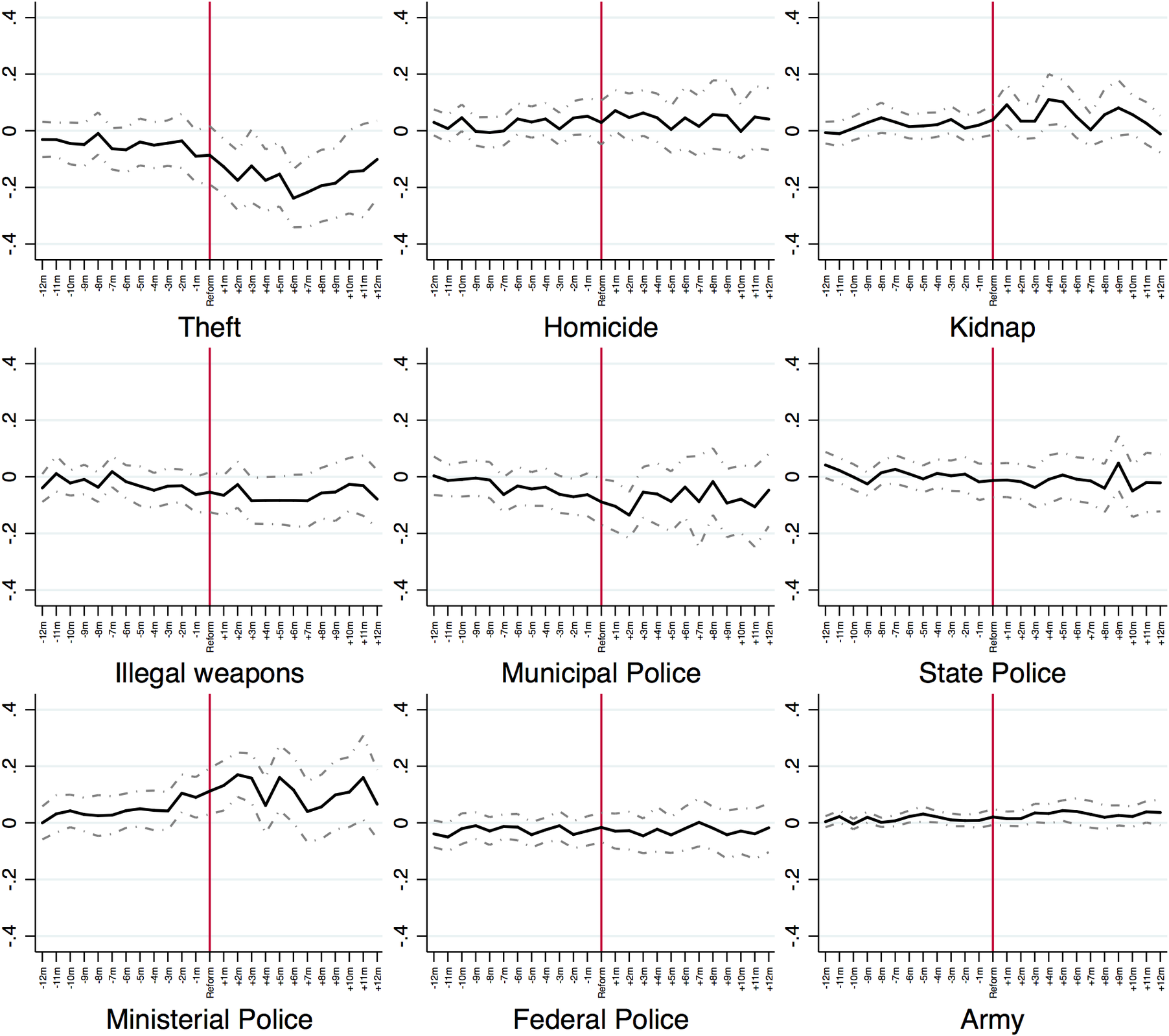

In Figure 4, we present coefficients from OLS models for monthly arrests by crime before and after the reform according to crime. Our sample has fewer arrests for theft after the reform and slightly more prisoners arrested for kidnapping. We also inquire whether the composition of our sample by arresting authority changes with the reform. As shown in Figure 4, our sample’s proportion of arrests by the armed forces, federal, and state police do not change with the reform. We have a slight increase in the proportion of prisoners in our sample arrested by the ministerial police and a decrease in arrests by the municipal police.

Figure 4. Proportion of Arrests around Reform by Crime and Coercive Institution

The fact that the post-reform sample sees declines in arrests for theft and arrests by municipal police poses a problem for our analysis. Table 3 shows that individuals arrested for theft are a substantial portion of our sample and are actually tortured at high rates, though they are far from the most likely to be victims. Moreover, municipal police torture at lower rates than other authorities do and although this would work against our argument that the reform reduces torture, we need to account for this potential confounding factor as well. To deal with this problem we cannot simply run a regression controlling for these covariates, as we have just shown that some of these variables are themselves affected by the treatment of interest. Consequently, we follow the procedure set out in Imai et al. (Reference Imai, Keele, Tingle and Yamamoto2011) and its implementation in Imai and Yamamoto (Reference Imai and Yamamoto2013) to explore whether and how these factors mediate the effect of the reform in reducing torture. They propose a method to estimate both the average causal mediation effect, or the effect of the mediator, and the average direct effect of the treatment. Briefly, we estimate two equations—one for the moderator (M ist) and one for the dependent variable (Y ist):

and

where α is an intercept, τ is the coefficient on the treatment, β is the effect of the moderator, and ![]() $$ \lambda $$ and

$$ \lambda $$ and ![]() $$ \gamma $$ are year and judicial district effects, respectively. Their method then generates predictions for the mediator under treatment and control, and it then uses these values to predict missing values in a potential outcomes model that includes the mediator and the treatment. Their method uses bootstrapping to estimate uncertainty.

$$ \gamma $$ are year and judicial district effects, respectively. Their method then generates predictions for the mediator under treatment and control, and it then uses these values to predict missing values in a potential outcomes model that includes the mediator and the treatment. Their method uses bootstrapping to estimate uncertainty.

The purpose of this exercise is not to identify the causal pathway but rather to see whether, while being generous to the hypothesis that our results are being driven by these imbalances in posttreatment covariates, we find evidence that the mediator explains our effect. We run this for each of our dependent variables twice—once using arrests for theft as the moderator and again using arrests by the municipal police. The results from this test are reported in Table 7; the direct effect remains when accounting for the mediation, which appears to be quite small in substantive terms across all the models.

Table 7. Mediators

Note: Results from a mediation analysis testing whether the pre- and post- treatment imbalance in arrests by the municipal police and arrests for theft is driving our results. All models include socioeconomic characteristics. Bootstrapped standard errors clustered by judicial district are reported in parentheses. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.10.

Robustness tests

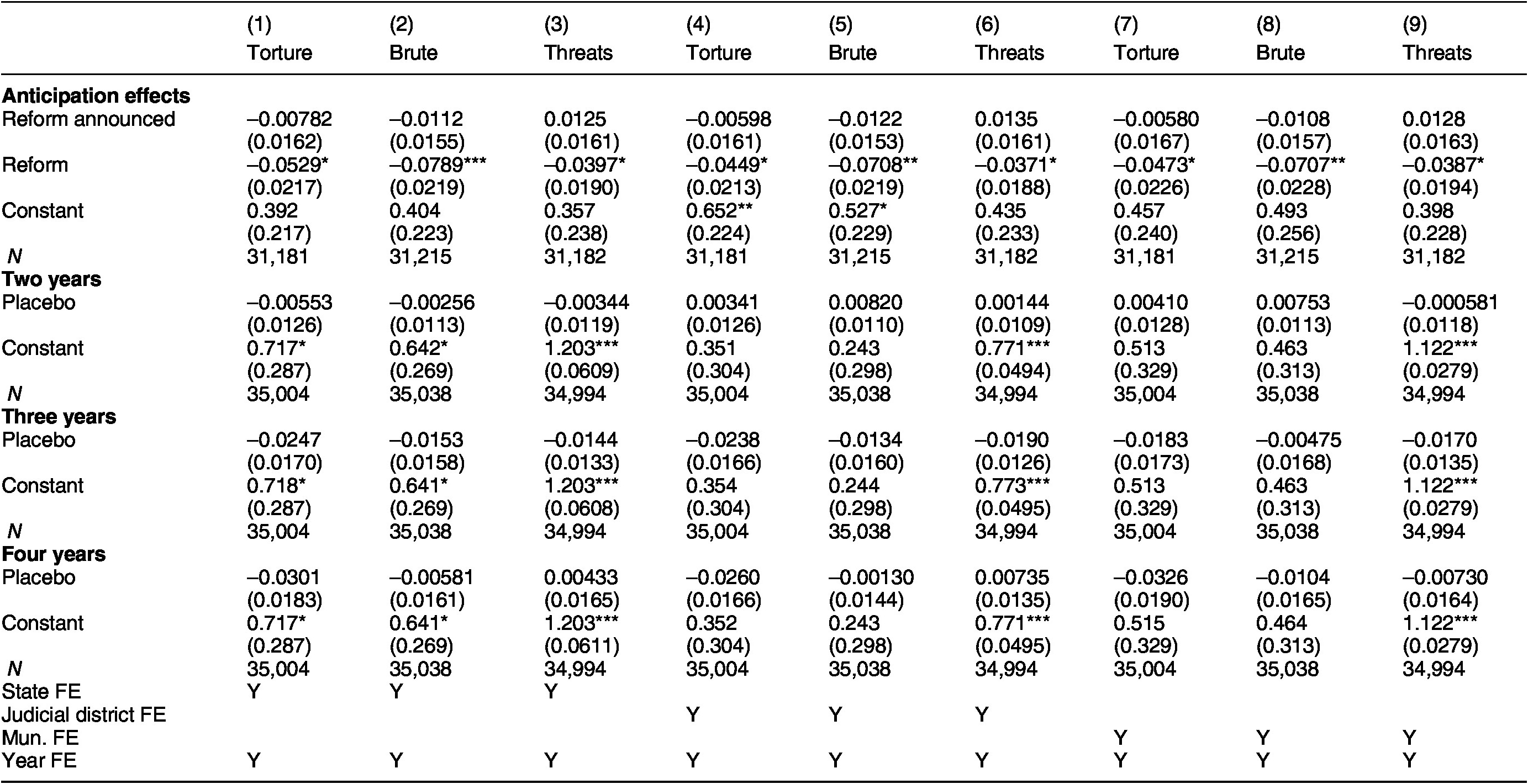

In Table 8 we present a series of robustness tests. First, we test whether there is a detectable effect of jurisdictions anticipating the reform’s implementation. Each state legislature published official declarations announcing the timetable for the reform’s implementation in 2014. We constructed a variable to indicate the period after the reform’s timetable was first announced but before the reform was actually implemented. This means we then have a sample divided into the pre-reform but pre-announcement era, the post-announcement but pre-reform era, and the reform era. When we ran these models, we did not find anticipation effects.Footnote 13

Table 8. Placebo Tests for the Criminal Justice Reform

Note: Entries are estimated coefficients from OLS regressions for placebo tests that move the start dates of the reform two, three, and four years before the actual dates. All models include socioeconomic characteristics. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered at the judicial district level. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.10.

We implemented additional placebo tests in which we artificially move the date of the implementation of the reform beyond our “announcement period” to two, three, and four years prior to the actual implementation. We repeat the specifications from the main model analyzing these “faked” reforms truncated at the date of the real reform. We report the coefficients on the artificial reform variable in Table 8 and find no significant effects across any of the models.

Lastly, in section 4.3 of the Online Appendix, we rerun our tests and use coarsened exact matching on crime, arresting authorities, and sentencing status to ensure balance in covariates that may be unbalanced in the pre- and post-reform periods and related to the outcome variables. Our results hold after we match on these variables. The Online Appendix also shows that the results are robust to the exclusion of any state in Tables A10–11.

Militarized Security Interventions and Organized Crime

Our theoretical approach proposes that militarized security interventions and organized crime threats increase torture, thus working in the opposite direction of the criminal justice reform. To model the effect of militarized security interventions, this part of the analysis focuses on the Calderón presidency, when the armed forces and federal police were deployed to assist local police to combat crime through “joint operations.” Our theoretical approach stresses that arrests during these security interventions should be associated with more torture. Our model specification is as follows:

where ![]() $$ {y}_{ist} $$ is a dichotomous indicator for abuse reported by prisoner

$$ {y}_{ist} $$ is a dichotomous indicator for abuse reported by prisoner ![]() $$ i $$ and

$$ i $$ and ![]() $$ {D}_i $$ is an indicator variable for treatment or whether the prisoner was arrested in a state during a joint operation. The model also includes

$$ {D}_i $$ is an indicator variable for treatment or whether the prisoner was arrested in a state during a joint operation. The model also includes ![]() $$ k $$ individual covariates as well as unit and time fixed effects (

$$ k $$ individual covariates as well as unit and time fixed effects (![]() $$ {\lambda}_s $$ and

$$ {\lambda}_s $$ and ![]() $$ {\gamma}_t $$, respectively).

$$ {\gamma}_t $$, respectively).

Results are presented in Table 9. Model 1 shows that militarized operations substantially increase torture by almost 10 percentage points. Model 2 shows that the effect of militarized security interventions persists even after controlling for municipal-level turf wars, which also increase torture. To define turf wars, we add a dummy variable indicating that an arrest took place either in the same year as a war or where a turf war had occurred within the prior two years. As expected, turf wars are associated with more torture. Model 3 interacts joint operations with the prison jurisdiction and shows that, as expected, federal prisoners are subject to significantly more torture, but finds that joint operations worsen conditions for state and federal prisoners alike, lending support to our argument that these militarized interventions also increase torture among state-level police forces. Model 4 interacts joint operations with the arresting authority. The armed forces and federal police engage in significantly more torture than state, ministerial, and municipal police forces. There is no evidence, however, that joint operations have heterogeneous effects depending on the arresting authority.

Table 9. Effects of Militarized Security Interventions on Torture

Note: Entries are coefficients from OLS regressions, and standard errors, clustered by municipality, are in parentheses. All models include socioeconomic characteristics. We truncate the data to cover all the arrests until the end of 2012, covering the Calderón administration’s interventions but excluding arrests after that period. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.10.

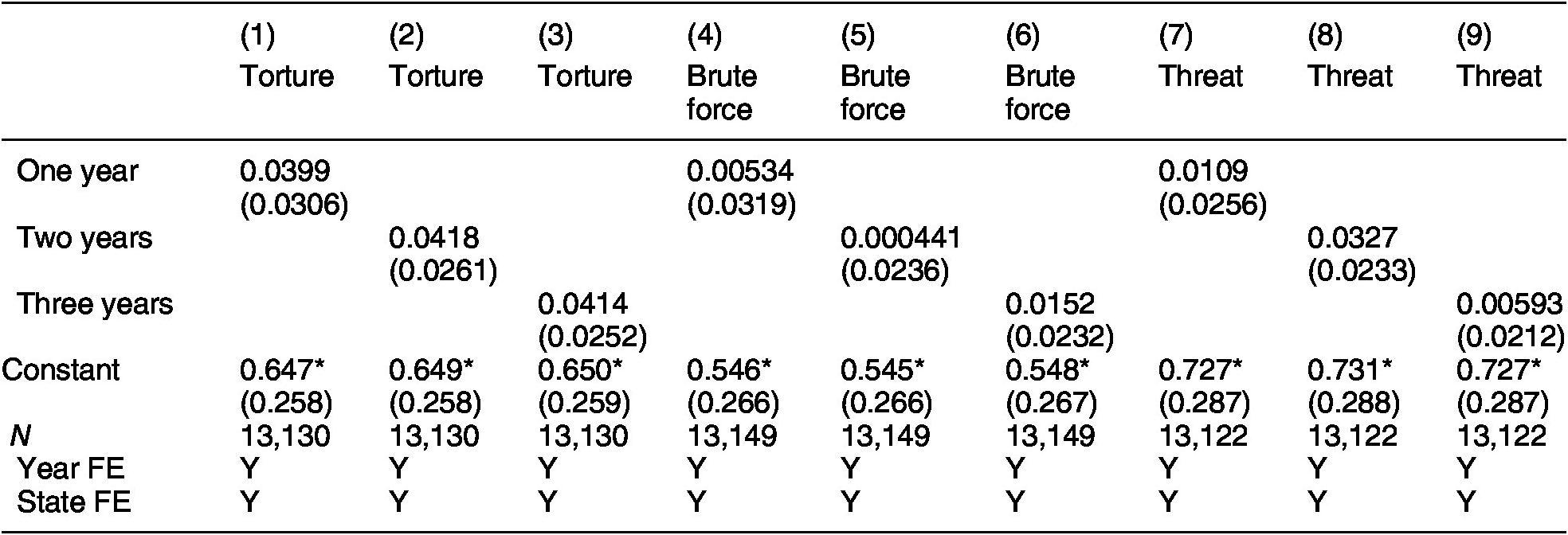

In Table 10 we present placebo tests by artificially moving the date of joint operations back by one, two, and three years. We find no significant results for these “fake” joint operations. In Section 4.5 of the Online Appendix, we also explore the data for parallel trends and demonstrate that torture has similar trends in states with and without joint operations prior to the start of these security interventions. We also include models with state-specific time trends. The results are robust.

Table 10. Placebos for Federal Military Interventions

Note: Entries are coefficients from OLS regressions where we artificially move the dates of federal military interventions known as “joint operations” back by one, two, and three years. Standard errors, clustered by municipality, are reported in parentheses. Data for these tests truncate all data at the beginning of the real federal intervention to avoid including data after the real treatment is applied. All models include socioeconomic characteristics. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.10.

The Criminal Justice Reform and Organized Crime Threats

Our theoretical approach proposed that the criminal justice reform should still grant leeway to victimize suspects accused of organized crime. It also proposed that high levels of threat from organized crime should mitigate the effects of the reform. To test these hypotheses, Table 11 presents the results of various models, and analogues for brute force and threats are presented in Appendix Tables A17–A18.

Table 11. Heterogeneous Effects of the Reform: Organized Crime and Coercive Institutions

Note: Entries are coefficients from OLS regressions. Standard errors, clustered by municipality, are in parentheses. All models include socioeconomic characteristics. Analogous tables for brute force and threats are presented in Appendix Tables A17–18. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, +p < 0.10.

Model 1 interacts the reform with turf wars. It shows that these basically eliminate the effects of the reform, although the standard errors are large because in the post-reform era there is a small sample size of arrests during a turf war. Model 2 interacts the reform with municipal-level homicide rates. The results suggest that higher homicide rates translate into more torture. In contrast to turf wars, high homicide rates do not make the reform less effective. Model 3 interacts organized crime with the reform. As mentioned previously, the reform included a list of crimes that are excluded from some procedural protections because they are bundled into the category of “organized crime.” To operationalize this, we use the following crimes: kidnapping, drug commerce, possession of illegal weapons, and homicide. Since the law defines “organized crime” as a federal offense and those accused of this tend to be detained in federal prisons, our measure of organized crime also includes federal prisoners.Footnote 14 Model 3 shows that prisoners accused of organized crime are subject to more torture. The model also demonstrates that, as expected, the reform does not constrain abuses against criminals accused of organized crime. Model 4 shows that the reform reduces torture significantly more when the arresting authority is the ministerial police. While we note that the armed forces and federal police appear to perpetrate less torture after the reform, the standard errors are too large to reach statistical significance (likely because of the small number of observations for those arrested by these authorities after the reform).

Models in Tables 9 and 11 demonstrate that militarized interventions and the criminal justice reform have opposite effects on torture. As we examine five authorities in these models—municipal police, state police, ministerial police, the federal police, and the military—we need to correct for the increased possibility of a false discovery in these models. In the Online Appendix, we employ the approach in Benjamini and Hochberg (Reference Benjamini and Hochberg1995)Footnote 15 to control for the false discovery rate. In terms of the reform, we find that the coefficient on ministerial police remains significant. As we do not find significant heterogeneity by authority in the corresponding model in Table 9, we do not run it for joint operations. In the Online Appendix section 7, we further calculate marginal increases in torture holding the arresting authority constant. Again, we correct for the increased possibility of a false discovery and find that, consistently, torture and other forms of abuse drop significantly with the reform when the arresting authority is the ministerial police. It is at this stage in the process when coerced confessions, evidence fabrication, and witness intimidation are more likely to be carried out and where the reform has imposed more constraints. Marginal effects for the federal police and the armed forces are also negative, but they do not reach statistical significance. Finally, we find strong positive effects for the ministerial, municipal, and federal police for the case of joint operations. These results support our theory that when regular police forces act alongside the armed forces, the former engage in more torture.

Conclusion

Our paper tackles a fundamental question about the nature of the state’s coercive apparatus: how do societies develop and institute more humane approaches to criminal justice? While police brutality can take many forms, this paper focuses on one of its most morally transgressive and outrageous manifestations: torture. The paper provides evidence of the role of two factors accounting for institutionalized police brutality in democratic states.

First, we have argued that criminal justice institutions strongly influence police behavior. Inquisitorial criminal justice systems, while reformed in Europe two centuries ago, persisted in Mexico and many other Latin American countries until recently. Prosecutors and police in Mexico came to systematically rely on coerced confessions to resolve cases, and judges allowed these as admissible in court even when there was evidence of physical mistreatment. This created a disturbing path dependency—institutions that began relying on coerced confessions never invested in investigative capacity, which meant that the Mexican criminal justice system became utterly incapable of sorting criminals from innocent people. The cruelty of the system manifested not only in the violence it imposed but also in the high number of wrongful convictions it likely produced after torturing people into making false confessions. Moreover, the data presented suggest that the inquisitorial criminal justice system would torture—and subsequently convict—as many prisoners accused of common theft as those accused of more serious crimes, including homicide. These brutal coercive institutions persisted in Mexico years after the democratic transition.

A second factor that accounts for the persistence of abusive coercive practices under democracy relates to rising levels of crime and insecurity. When criminal groups began to fight bloody turf wars in Mexico, police forces responded with more brutality. Rising insecurity also brought the adoption of heavy handed security polices—including the deployment of the armed forces—that deepened authoritarian tendencies in police forces. The military’s mission is predicated on the use of force. Working alongside the armed forces, regular police were imbued with equipment, tactics, and a mindset that caused systematic increases of torture. Police militarization is a common phenomenon not only in Mexico but also in other Latin American countries (Flores-Macías and Zarkin Reference Flores-Macías and Zarkin2019). Our findings bolster the notion that these security strategies erode protections for basic rights that many citizens of democracies take for granted.

Despite this grim picture of the institutionalization of torture under democracy, our paper offers room for optimism. The paper demonstrates that the reform of the inquisitorial criminal justice system and the introduction of more judicial checks on police, a common trend in the region, have worked to decrease human rights abuses in Mexico. Further research is needed to understand how criminal justice reforms influence human rights in the broader Latin American context, where during the last decades there has been a regional trend towards the abolition of these inquisitorial institutions.

Our findings also contribute to the body of work on the micro-logic of police behavior, which, until now, mostly focuses on the U.S. Following Mummolo (Reference Mummolo2018b), we distinguish between two understandings of police brutality. One emphasizes potentially immutable officer traits as the culprits of police misconduct, including issues such as authoritarian personalities, racial biases, machismo, cynicism, aggression, and substance abuse. According to this line of investigation, torture could be explained as an inhumane act by sadistic individuals hard to restrain through institutional reforms. Our paper supports a second line of investigation that emphasizes the effect of institutional and organizational norms on police violence and that understands the phenomenon as one that can be controlled with institutional design. In particular, we have argued that the introduction of stronger judicial checks on prosecutors and police is essential to restrain abuse. More research is needed to trace the evolution of jurisprudence and the behavior of courts on procedural rights in criminal trials.

Another critical avenue for further research is how society responds to these reforms and whether mechanisms of electoral accountability might restrain or enable authoritarian policing practices. Reforms that constrain police might plausibly lead people to associate the incidence of crime in their community, regardless of whether crime rates change, with new procedural protections built into the criminal justice system and generate societal pressures to reverse these reforms. Moreover, while one may reasonably expect opposition to an abusive police force in a democracy—repression runs counter to democratic norms and any given individual may reasonably fear falling victim to abuse—fear of crime and insecurity might engender societal preferences for sadistic punishments and abusive policing. Another issue to consider is that individuals who have not had personal contact with the criminal justice system might be unaware of or indifferent to the suffering it engenders. Additionally, a question for further research is how criminal behavior changes in response to an institutional overhaul of criminal prosecution. If police perceive that the institutional constrains severely restrain or weaken their capacity to imprison criminals, the backlash might come from within coercive institutions. As in the case of Venezuela and Brazil, police could begin to act as vigilantes and engage in extrajudicial killings to combat crime (Kronick and Hausman Reference Kronick and Hausman2019; Magaloni, Franco Vivanco, and Melo Reference Magaloni, Vivanco and Melo2020).

Lastly, while our paper has optimistic implications about the prospect of restraining torture, we note that high levels of brutality still persist in Mexico. Moreover, the reform justifies exempting many offenses by tying them to the threat of organized crime. Weak procedural protections for these offenses and the military involvement in law enforcement continue to open the door to abuse.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000520.

Replication materials can be found on Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JORLQM.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.