Introduction

In recent years, high levels of refugee migration have led to social tensions, political conflict, and right-wing political backlash (Alrababa’h et al. Reference Alrababa’h, Dillon, Williamson, Hainmueller, Hangartner and Weinstein2019; Bansak, Hainmueller, and Hangartner Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2016; Braithwaite et al. Reference Braithwaite, Chu, Curtis and Ghosn2019; Ghosn, Braithwaite, and Chu Reference Ghosn, Braithwaite and Chu2019; Hangartner et al. Reference Hangartner, Dinas, Marbach, Matakos and Xefteris2019; Marbach and Ropers Reference Marbach and Ropers2018). We explore international humanitarian aid as a potential mechanism by which these tensions can be reduced, studying how aid affects violence targeting refugees. Although aid is often portrayed as increasing hostility from host-country nationals, we present quasi-experimental evidence that cash transfers to refugees do not increase, and may in fact reduce, anti-refugee violence.

What should we expect from cash transfers to refugees? Existing literature and our fieldwork raise concerns that humanitarian aid exacerbates violence targeting refugees. The humanitarian community is concerned about potential increases in resentment among host-country nationals that refugees receive assistance and that the aid is “unfairly” distributed (UNDP 2019; World Bank 2013). Aid may exacerbate hostility through distributional concerns, negatively affecting natives’ perceived relative well-being or activating concerns over resource scarcity (Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996; Dahlberg, Edmark, and Lundqvist Reference Dahlberg, Edmark and Lundqvist2012; Dancygier Reference Dancygier2010; Dustmann, Vasiljeva, and Damm Reference Dustmann, Vasiljeva and Damm2018). We also know that increased exposure to refugee populations and camps, with their concomitant humanitarian aid responses, may increase hostility toward refugees (Hangartner et al. Reference Hangartner, Dinas, Marbach, Matakos and Xefteris2019; Zhou Reference Zhou2018). However, the role of aid specifically in causing this hostility has not been explored.

Despite predictions that humanitarian aid exacerbates anti-refugee violence, a number of factors suggest reasons why it may not do so. If aid mitigates the perceived adverse economic consequences of refugees for host communities, then natives may be less likely to use violence as a strategic tool (to impede refugees from causing economic harm, to extract transfers, or to enact vengeance) or as an instinctual emotional reaction (caused by anger). In this case aid may reduce hostility by increasing refugees’ capacity to appease hosts through offering help (e.g., sharing aid) and through buying locally and boosting demand for local goods and services. Furthermore, aid may allow refugees to both avoid contact with potential aggressors (e.g., by substituting public with private transport) and increase positive contact with locals.Footnote 1

To study how international humanitarian aid affects anti-refugee hostility, we collected survey data from over 1,300 Syrian refugee households in Lebanon, a country with a population of 4.5 million that has seen the arrival of more than a million refugees since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011. As is typical for most refugees today, with only one third of the world’s refugees living in camps, the vast majority of Syrian refugees (and all respondents of our survey) live in rented apartments, rooms, and improvised shelters in Lebanese towns.

For our empirical test, we leverage the fact that approximately half of the refugees in our sample were as-if randomly assigned to receive cash transfers from the UN refugee agency (UNHCR): only refugees in communities at or above 500 meters altitude were eligible for these transfers because UNHCR used an altitude-based criterion to target refugees residing in colder climates during the winter months. Hence we estimate a regression discontinuity design (RD), comparing refugees in communities slightly below 500 meters altitude (control group) to those living in communities slightly above 500 meters altitude (treatment group).

Our RD estimates suggest that cash transfers to refugees did not increase anti-refugee violence and may have reduced it. Exploring why aid did not exacerbate anti-refugee hostility, we find evidence of possible mechanisms including that aid allows recipients to indirectly compensate locals through higher demand for local goods and services, directly benefit locals by offering help and sharing aid, and reduce contact with potential aggressors. We contribute to the literature on the causes of anti-refugee violence (Benček and Strasheim Reference Benček and Strasheim2016; Falk, Kuhn, and Zweimueller Reference Falk, Kuhn and Zweimueller2011; Jäckle and König Reference Jäckle and König2017; Koopmans Reference Koopmans1996; Onoma Reference Onoma2013), which has previously examined a range of causes including political and economic drivers, by examining the role of international humanitarian aid.

Methods

In this section we provide a brief summary of the cash transfer program and our empirical strategy. In our web appendix, we provide a detailed description of the aid program and survey. We also report full descriptive statistics and correlates of anti-refugee violence as well as conventional tests of the internal validity of our RD.

The Cash Transfer Program

In November 2013, the UN started a new aid program for almost a hundred thousand Syrian refugee families in Lebanon. The goal of the program was to help refugees stay warm, dry, and healthy during the cold, wet winter months. Eligible refugee households received an ATM card from the UN. Between November 2013 and March 2014, the UN transferred about $US100 per month to a bank account linked to each ATM card, $US575 in total over the course of six months (which is roughly $US1,000 in PPP terms). Since the program was only intended for the winter, it ended in April 2014.

Regression Discontinuity Design

We rely on a criterion that only refugees in communities at or above 500 meters altitude were eligible for transfers. According to a senior UNHCR official we interviewed, the goal of the program was to target refugees in colder climates, and they selected a round number (500) as the altitude cutoff subject to their program’s budget constraint. Within communities above 500 meters altitude, all Syrian households that met a number of proxy poverty criteria received the transfers. Hence, we estimate an RD, comparing refugees in eligible “poor” households slightly above 500 meters altitude (treatment group) to otherwise eligible “poor” households living in communities slightly below 500 meters altitude (control group).

We sought to collect survey data on all 1,851 “poor” refugee households residing between 450 and 550 meters altitude, and we successfully interviewed 1,358 households (73% response rate, 74.1% in control, and 72.7% in treatment).Footnote 2 Our survey was administered in April and May 2014—that is, about six months after the start of the program.

Treated and control communities cover the entire mountain range along the Lebanese coast.Footnote 3 Formal statistical tests do not suggest systematic differences between treated and control communities in terms of geography (latitude/longitude), demography (number of Lebanese and refugees), climate (temperature and precipitation), economy, and religious sect.Footnote 4 We thus have little reason to believe that culture and attitudes toward strangers, which are presumably correlated with the variables used in our balance tests, would vary discontinuously around the cutoff. Finally, there is no evidence that other aid programs vary discontinuously around the cutoff.Footnote 5

Following Imbens and Lemieux (Reference Imbens and Lemieux2008), we implement the RD by running local regressions of the form

where Ai is the altitude where household i resides. The term f(Ai) is a polynomial function of Ai. We follow the suggestion of Imbens and Lemieux (Reference Imbens and Lemieux2008) and use linear and quadratic functional forms for f(Ai), and allow for different slopes of the regression function on both sides of the cutoff. The parameter ![]() $ \beta$ measures the local average treatment effect (LATE) of aid on outcome Y i at A i = 500.

$ \beta$ measures the local average treatment effect (LATE) of aid on outcome Y i at A i = 500.

Descriptive Statistics

The average household in our sample is composed of three children and two adults. A total of 28% of heads have no schooling or did not complete primary schooling, while 33% completed primary school, 30% middle school, and 9% secondary school or higher. A total of 89% of households rent rooms; the remainder lives in improvised shelters. Household monthly food and nonfood consumption is $US320 and $US460, respectively.Footnote 6 Household members worked a total of 11.8 days during the past 4 weeks, with a labor income of $US182. A total of 76% of respondents report casual labor in shops, agriculture, or construction as their main occupation. The ratio of Syrian to Lebanese households is 60:282 in treatment communities and 58:283 in control communities.

Measurement of Hostility

We asked survey respondents whether Lebanese in the community had been physically aggressive to household members in the past six months. In a separate question, we asked about verbal abuse perpetrated by Lebanese community members in the past six months. We did not ask about other acts of violence committed by Lebanese.

The precise wording of the questions was

• “In the last six months, have Lebanese living in this community been physically aggressive with members of your household often, sometimes, rarely, or never?”

• “In the last six months, have Lebanese living in this community said things to insult or hurt members of your household often, sometimes, rarely, or never?”

Our fieldwork suggests that refugees do not generally trust Lebanese authorities enough to report crimes like assault, hence self-reported data is perhaps the most reliable data source, even with its limitations.Footnote 7

A total of 5.2% of respondents report verbal assault, and 1.3% report physical assault by Lebanese community members. We code respondents who answer “often” or “sometimes” as having experienced assault. Results are robust to including “rarely” responses as incidences of violence, as shown in the appendix.Footnote 8 We inquired about the reason for the verbal or physical assault by asking respondents the following question:

• “What do you view as the reasons for the verbal or physical attack?”

Response options included:

a) “She/he/they think that my household takes away his/her/their jobs” (40% of respondents)

b) “My household receives assistance (e.g., food or money) from organizations” (17% of respondents)

c) “She/he/they think that my household’s presence has increased prices” (16% of respondents)

d) “She/he/they do not like the way I and/or members of my household dress” (8% of respondents)

e) “She/he/they think that my household’s presence has increased crime” (7% of respondents)

f) “She/he/they think that I and/or members of my household are lazy” (4% of respondents)

g) Other reason (7% of respondents)

Respondents believe that economic consequences of the refugee influx for host communities are the primary drivers of violence, with (a) higher unemployment and (c) inflation accounting for more than half (56%) of the hostility that refugees experience. Respondents’ perception that their effect on unemployment is the primary cause for violence aligns with correlational analysis of our survey data: we find a statistically significant negative correlation between the daily wage rate of agricultural labor and the number of refugees in a community, controlling for the number of Lebanese residents. A 1% increase in the size of the refugee population is associated with a 0.05% decrease in local wages. Furthermore, we find that a refugee’s labor supply (hours worked) is a statistically significant predictor of violence in our data.

In contrast, a non-negligible share of respondents (17%) stated that receiving humanitarian aid was one of the reasons for anti-refugee violence (reason b). During fieldwork and discussions with government and nongovernmental organizations we often encountered the view that humanitarian aid for refugees is further fueling hostility in host communities. Allegedly, members of host communities are furious that Syrians receive humanitarian aid, while host communities receive little compensation for the supposed negative impact of the Syrian refugee crisis on Lebanese wages.Footnote 9

Results and Discussion

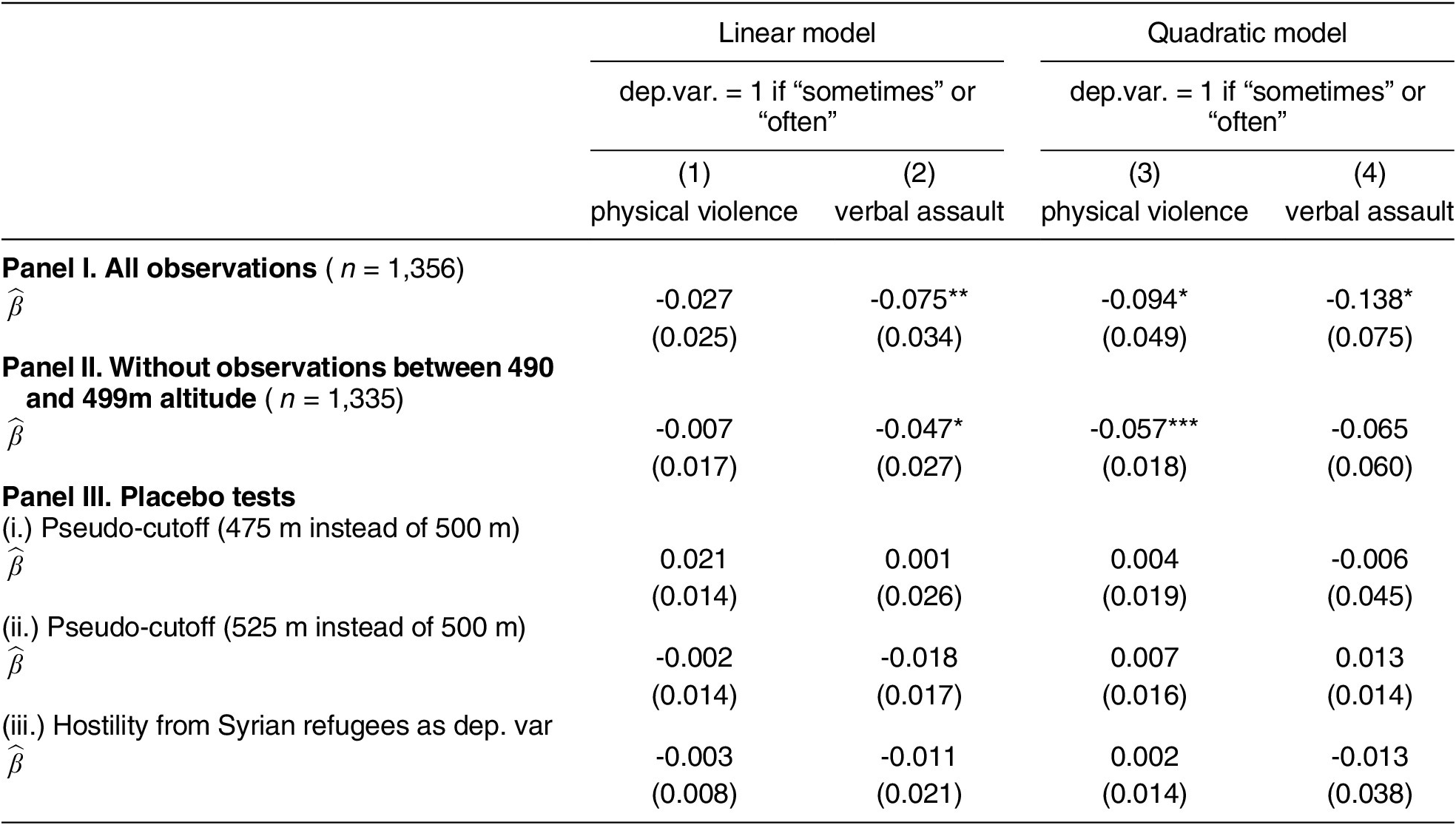

Figure 1 suggests that cash transfers did not increase hostility toward refugees, and if anything they may have reduced it. Point estimates are consistently negative and confidence intervals rule out large positive effects. As shown in Figure 2 and the appendix, results are robust to numerous modeling choices. A linear regression modelFootnote 10 produces our most conservative estimates, and we also present results dropping the 490–499-meter altitude bin with relatively high incidences of violence. The RD estimates with (and without) the outlier bin show a decrease of 2.7 (0.7) percentage points in physical violence and 7.5 (4.7) percentage points in verbal assault. Table 1 presents these results and also shows results from a quadratic model,Footnote 11 which produces even larger negative effect estimates.Footnote 12Figure 2 shows results across a range of bandwidths when we restrict the sample to observations closer to the cutoff. Point estimates remain consistently negative and confidence intervals refute any meaningful increase in violence.

Table 1. Aid and Anti-refugee Violence

Note: This table reports ordinary least square estimates of ![]() $ \beta$ in Equation 1 with a linear polynomial (columns 1 and 2) and quadratic polynomial (columns 3 and 4), and in parentheses are robust standard errors clustered at the community level. In Panels I, II, III(i.), and III(ii.), columns 1 and 3 (2 and 4), the dependent variable is a 1/0 dummy: 1 if Lebanese have “sometimes” or “often” been physically (verbally) aggressive to the respondent or members of the household in the past six months and 0 if “rarely” or “never.” In panel III(iii.), columns 1 and 3 (2 and 4), the dependent variable is a 1/0 dummy: 1 if Syrians in the community have “sometimes” or “often” been physically (verbally) aggressive to the respondent or members of the household in the past six months and 0 if “rarely” or “never.” * p < .10, ** p < .05, *** p < .01.

$ \beta$ in Equation 1 with a linear polynomial (columns 1 and 2) and quadratic polynomial (columns 3 and 4), and in parentheses are robust standard errors clustered at the community level. In Panels I, II, III(i.), and III(ii.), columns 1 and 3 (2 and 4), the dependent variable is a 1/0 dummy: 1 if Lebanese have “sometimes” or “often” been physically (verbally) aggressive to the respondent or members of the household in the past six months and 0 if “rarely” or “never.” In panel III(iii.), columns 1 and 3 (2 and 4), the dependent variable is a 1/0 dummy: 1 if Syrians in the community have “sometimes” or “often” been physically (verbally) aggressive to the respondent or members of the household in the past six months and 0 if “rarely” or “never.” * p < .10, ** p < .05, *** p < .01.

Figure 1. Aid and Anti-refugee Violence

Figure 2. Aid and Anti-refugee Violence: Smaller Bandwidth

Placebo tests support these findings. The first test consists of using 475 and 525 meters altitude as pseudo-eligibility cutpoints, which yield precise point estimates close to zero. In the second placebo test, we replace the dependent variable with verbal or physical assault from other Syrian refugees (as opposed to Lebanese locals). According to our theoretical predictions about the drivers of anti-refugee violence, we would not necessarily expect any effect of aid on hostility between refugees, and in line with this reasoning we get precise point estimates close to zero.Footnote 13 We provide further robustness tests in the appendix.Footnote 14

Why is it that humanitarian aid does not exacerbate anti-refugee hostility? One possibility is that aid allowed refugees to take steps that mitigate their risk of violence, such as indirectly benefiting locals through higher demand for local goods and services, directly benefiting locals by offering help and sharing aid, and reducing contact with potential aggressors (e.g., by substituting public with private means of transport). Our data provide evidence of these mechanisms: for example, we asked respondents, “Do members of your household provide help to Lebanese living in this community such as help looking after their children, help when they are sick, help with housework, or giving money?” and find a large increase in the propensity to help hosts at 500 meters altitude (see Figure 3). Furthermore, food consumption (in the past 30 days) jumps by $US70 at 500 meters altitude, suggesting that aid recipients spend roughly 70%Footnote 15 of their aid (UNHCR transferred roughly $US100 in the 30 days prior to data collection) in the local economy.Footnote 16 The contact with refugees on these occasions may also have increased hosts’ acceptance. Ghosn, Braithwaite, and Chu (Reference Ghosn, Braithwaite and Chu2019), for example, find that Lebanese who have had contact with Syrians are significantly more likely to support hosting refugees.Footnote 17 Finally, Figure 3 suggests that aid may have allowed refugees to avoid contact with potential aggressors by substituting public with private transport. More rigorous tests of these hypotheses remain on the agenda for future research.

Figure 3. Possible Mechanisms

A caveat of our research design is external validity. Our results are confined to poor refugees in host communities around 500 meters altitude in winter, which is not a representative population or season. If anti-refugee violence is generally lower during winter (e.g., because refugees and hosts have less contact as both stay at home more) and cash transfers indeed reduce violence, then we should expect the treatment effect in nonwinter months to be larger than what we report in this article.Footnote 18 Furthermore, the effect of cash transfers on anti-refugee violence may change as a refugee crisis wears on and as the baseline rate of intergroup tensions changes.Footnote 19

To draw policy implications for cash transfers and anti-refugee violence in a given situation, we must consider policy constraints and alternatives. In some contexts market capacity or infrastructure will be important constraints. Our evidence, confined to Syrian refugees in Lebanon residing between 450 and 550 meters altitude, suggests that these local economies adjusted well to refugees receiving cash transfers: we find large positive effects on food consumption of recipients and no effects on local prices; that is, market supply accommodated the increased demand of cash transfer recipients. In other contexts, however, widespread programming could cause inflation (if market supply is unable to accommodate large shifts in demand) and may thereby increase resentment/hostility toward refugees. Further research should study alternative humanitarian interventions to understand conditions under which aid may have heterogeneous effects on hostility. If humanitarian aid mitigates anti-refugee hostility because of positive spillover effects on host communities, further research should consider how to realize these benefits, such as delivering aid directly to host communities (e.g., cash transfers to the local Lebanese population, hospitals, schools, etc.), possibly explicitly linked to the community’s role in hosting refugees. In Lebanon, a number of organizations provide assistance for host communities with the goal of reducing tensions. Testing for the effects of such direct transfers to hosts, including whether they generate reductions in anti-refugee sentiments or have adverse effects, is, we believe, a fruitful avenue for future research.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000349.Replication materials can be found on Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/5LAZ54.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.