On March 28, 2011, Juan Francisco Sicilia was murdered, a bystander fatally drawn into Mexico's bloody drug war. Juan Francisco was a 24-year-old student and the son of renowned poet Javier Sicilia. Upon learning of his son's death, the elder Sicilia published a heartfelt open letter in the news magazine Proceso (Sicilia Reference Sicilia2011). Linking Juan Francisco's case to the tens of thousands of other senseless killings in Mexico each year, the letter was at once a searing indictment of Mexico's criminals and politicians and an eloquent call to action. Sicilia urged his fellow citizens to take to the streets, using their voices, their bodies, and their pain to protest the wave of violence wracking their society. Hundreds of thousands responded enthusiastically, and soon the key refrain from Sicilia's letter—“¡Estamos hasta la madre!” or “We've had it up to here!”—was echoing across the country. Seemingly overnight, the poet had become one of Mexico's most influential activists (Archibold Reference Archibold2011; Moorhead Reference Moorhead2011; Padgett Reference Padgett2011).

Sicilia's story is clearly unique, but it raises a provocative question: When people are the victims of crimes, can this motivate them to become more active in politics? Education, socioeconomic status, age, gender, family history, and personality are all known to influence whether, and to what degree, individuals participate in politics.Footnote 1 Yet even the most comprehensive studies of political participation have never considered crime victimization as a potential cause of participation,Footnote 2 perhaps because prior research suggests that crime victims should be less politically active than their peers. Other negative shocks such as divorce (Kern Reference Kern2010) and job loss (Rosenstone Reference Rosenstone1982) are associated with decreases in voter turnout.Footnote 3 Crime might be expected to have an even stronger depressant effect because of its high costs, both monetary and psychological.Footnote 4 Indeed, crime victims are generally portrayed as distrustful (Brehm and Rahn Reference Brehm and Rahn1997; Carreras n.d.), unhappy (Powdthavee Reference Powdthavee2005), and withdrawn (Cárdia Reference Cárdia, Rotker and Goldman2002; Elias Reference Elias1986; Marks and Goldsmith Reference Marks, Goldsmith, Wood and Dupont2006; Melossi and Selmini Reference Melossi, Selmini, Hope and Sparks2000; Skogan Reference Skogan1990).

However, new research suggests that victimization may have some positive consequences. Bellows and Miguel (Reference Bellows and Miguel2009), Blattman (Reference Blattman2009), Shewfelt (Reference Shewfelt2009), and Voors et al. (Reference Voors, Nillesen, Verwimp, Bulte, Lensink and van Soest2012) find that after some civil wars, individuals who personally experienced wartime violence and trauma have increased rates of voting, community leadership, and civic engagement. Their evidence is contextually limited—drawn from fieldwork in Sierra Leone, Northern Uganda, Aceh, and Burundi—but their conclusions are persuasive. Other group-level studies also find heightened social capital, altruism, and political participation in war-affected communities (Bellows and Miguel Reference Bellows and Miguel2006; Gilligan, Pasquale, and Samii Reference Gilligan, Pasquale and Samii2011; Kage Reference Kage2011).

This article adjudicates between these two competing perspectives. Do crime victims really retreat from civic and political life? Or, like Javier Sicilia, do they increase their involvement in politics? Survey data from 70 countries in Latin America, Africa, North America, Europe, and Asia support the latter proposition. From Bolivia to Botswana, from Canada to Cambodia, and from Sweden to South Africa, individuals who report that they or their family members have recently been the victims of crimes talk about politics more than their peers, express greater interest in politics, and are more likely to attend marches, political meetings, and community meetings. This is true for victims of all types of crimes, whether violent or petty. So rather than being seen as disenchanted, disempowered, or disengaged, crime victims should be reconceptualized as political actors—indeed, as potential activists.

Though this article is primarily empirical, it begins with a short discussion of possible explanations for the positive relationship between crime victimization and political participation. The next section describes the survey data used in the article, outlines the data analysis procedures, and presents the results. The third section addresses threats to inference, including reverse causation, omitted variables, and neighborhood effects, and the penultimate section examines the implications of victims’ participation for democracy. The article concludes by suggesting that beyond crime, there may be a broader, more general relationship between victimization and participation.

WHY MIGHT VICTIMS TURN TO POLITICS?

This article presents strong evidence of a link between crime victimization and political participation and engagement. But why might crime victims turn to politics? To explain the positive relationship between exposure to wartime violence and postwar participation in Northern Uganda, Blattman (Reference Blattman2009) embraces post-traumatic growth theory, which suggests that personal growth and development can result from traumatic experiences (Tedeschi and Calhoun Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun1996). Post-traumatic growth is possible after a civil war, but Peltzer (Reference Peltzer2000) finds weak evidence of post-traumatic growth among crime victims. This is unsurprising, because post-traumatic growth can result only from “major life crises” that shatter an individual's assumptions about the world (Tedeschi and Calhoun Reference Tedeschi and Calhoun2004). Although some of the most famous victims-turned-activists have experienced traumatic losses—such as Carolyn McCarthy, who became a gun control advocate and won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives after her husband was killed and her son injured in a mass shooting (Barry Reference Barry1997; Marks Reference Marks1994)—less serious crimes drive others to action. Indeed, all types of crimes—even nonviolent crimes such as pickpocketing and bicycle theft—are associated with increases in political participation and engagement. Consequently, factors beyond post-traumatic growth must be motivating crime victims to participate in politics.

Most obviously, victims’ activism may seem instrumental. Victims commonly seek assistance from elected officials or lobby for policy changes that are narrowly related to the crimes they have suffered. For example, after her son was murdered in Queens, New York, Stephanie Guerra organized a small protest march to draw attention to his case and pressure the police to investigate (Barnard Reference Barnard2010). Similarly, a break-in at a family business prompted one respondent in the Citizen Participation Study to contact the mayor “to see what could be done to prevent it from happening” (quoted in Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). And victims often push for new laws designed to prevent the recurrence of specific crimes, as reflected in the plethora of laws named for victims, such as Megan's Law and the Adam Walsh Act in the United States and the Blumberg Laws in Argentina.Footnote 5

So is victims’ activism always linked to crime, a knee-jerk reaction to an immediate problem? Are victims just responding predictably to the shoe that pinches? Surveys suggest that, as expected, crime victims are especially concerned about crime. As compared to nonvictims, victims are more likely to see insecurity as a pressing public policy problem.Footnote 6 But among Latin American crime victims who participated in protests in 2009 and 2010, the vast majority (91%) demonstrated about issues other than crime—most commonly, the economy (23%), political matters (20%), and education (18%).Footnote 7 Because victims’ activism is broadly oriented across substantive areas, instrumental reasoning cannot fully account for their behavior.

Emotional and expressive factors, in contrast, are more viable explanations for crime victims’ increased levels of participation in a wide variety of civic and political activities. Crime victims may turn to politics because political participation mitigates the emotional consequences of victimization. Crime victims typically sustain long-lasting psychological harm (Macmillan Reference Macmillan2001), but victims who channel “their agony into activism . . . contribute significantly to their own healing” (Victim Services 1998). As demonstrated in Bejarano's (Reference Bejarano2002) study of homicide survivors in Ciudad Juárez, political organizing can be a source of social support for victims. Particularly when they band together with others who have suffered similar crimes, victims can form solidaristic ties and construct shared causal narratives about the harm that has befallen them (Jennings Reference Jennings1999; Stone Reference Stone1989).

Crime victims also tend to feel angry (Ditton et al. Reference Ditton, Farrall, Bannister, Gilchrist and Pease1999), and anger can be a powerful emotional catalyst for participation. On her way to a crime victims’ march in Mexico City, kidnapping survivor Marcela Hinojosa said she was protesting because she felt “a desire to scream” about what had happened to her (quoted in Thompson Reference Thompson2004). Candace Lightner and Cindi Lamb, the founders of Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), are even more candid. Lightner was “absolutely outraged” that the drunk driver who killed her daughter retained his California driver's license, so she founded MADD to deal with her anger (quoted in Bennion and Roach Reference Bennion and Roach2006). Similarly, when Lamb's infant daughter was injured by a drunk driver, she felt “pissed, outraged, just totally whacked out with anger.” Along with this anger came “enormous energy,” which she harnessed for political ends (quoted in Bennion and Roach Reference Bennion and Roach2006).

Finally, victims may participate in politics for expressive reasons. In the theory of expressive participation articulated by Schuessler (Reference Schuessler2000a; Reference Schuessler2000b), individuals participate in politics as a way of defining and reaffirming their identities. After a crime, victims may feel adrift and unmoored as they struggle to “find ways of making sense of what has happened” (Walklate Reference Walklate2007). Political participation can help them regain their footing. Rozowsky (Reference Rozowsky2002) recounts the stories of several South African crime victims who used activism to recast themselves as survivors, not helpless victims. After he was the victim of a home invasion robbery, one man organized a neighborhood watch group. Thanks to this action, he saw that he hadn't “shrivel[ed] up” after the crime; rather, he had “healed and flourished” (Rozowsky Reference Rozowsky2002). Similarly, two mugging victims were

fearful of the night, fearful to go back to the [area] in the evenings, so they decided to reclaim their streets. They sent notices around to various blocks of flats in the area and organized a street march. About twenty people came and they walked around the neighborhood in the evening holding candles. They felt more empowered by doing this. They repeated the exercise and found to their surprise that many other people were feeling anxious, but didn't want to take things lying down. This gesture made them feel that they were doing something and it was both liberating and empowering. (Rozowsky Reference Rozowsky2002)

For victims seeking to move beyond fear and submission, political participation and community activism can be valuable tools. Crime victims can derive emotional and expressive benefits from participation. Political participation allows victims to find social support and to constructively express their anger and frustration. Simultaneously, they are able to reimagine themselves as survivors, organizers, and leaders, reestablishing a sense of control and agency. So beyond post-traumatic growth and instrumental concerns, victims’ activism also has emotional and expressive motivations. Further qualitative research will be necessary to thoroughly understand victims’ reasons for participating in politics, but these complementary, nonrival explanations offer a plausible rationale for the strong, worldwide relationship between victimization and participation.

THE LINK BETWEEN VICTIMIZATION AND PARTICIPATION

Data and Descriptive Statistics

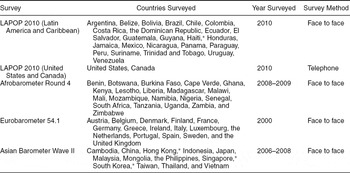

This article relies primarily on data from four regional barometer surveys (see Table 1 for details): LAPOP/AmericasBarometer 2010,Footnote 8 Afrobarometer Round 4,Footnote 9 Eurobarometer 54.1,Footnote 10 and Asian Barometer Wave II.Footnote 11 All the surveys use national probability samples of adults, with about 1,000 to 3,000 respondents per country.Footnote 12 Afrobarometer provides data from Sub-Saharan Africa, Eurobarometer from Western Europe, and Asian Barometer from East and Southeast Asia.Footnote 13 LAPOP 2010 includes most countries in Latin America and the Caribbean as well as the United States and Canada. Because the U.S./Canadian and Latin American/Caribbean versions of LAPOP use somewhat different questions and methods, these two regions are analyzed separately.

TABLE 1. Surveys

* Indicates that the country was surveyed, but is not included in the article because key variables were not recorded.

Though they are not purposefully designed as victimization surveys,Footnote 14 the regional barometers can be used to investigate the individual-level consequences of crime victimization (as in Carreras n.d.; Demombynes Reference Demombynes2009; Fernandez and Kuenzi Reference Fernandez and Kuenzi2010; Kuenzi Reference Kuenzi2006). Crime victimization is measured slightly differently in each survey. In Latin America and in North America, LAPOP asks if the respondent was the victim of a crime in the past 12 months, followed by a series of questions about the specific nature of the crime. Eurobarometer asks its respondents if they were the victims of burglaries or break-ins at their homes, physical assaults, or threats in the past 12 months. Afrobarometer asks if the respondents or their relatives were the victims of physical assaults or home burglaries in the past 12 months. Asian Barometer asks if the respondents or their relatives had vehicles or personal property stolen, had their homes broken into, or were the victims of physical violence in the past 12 months. These questions are the basis for this article's key independent variable: reported crime victimization (Victim). The Victim variable is coded 1 if the respondent said he or she (or his or her relatives, for the African and Asian data) was the victim of any crime in the past 12 months. Victim is coded as 0 if the respondent said that he or she (and his or her relatives, for the African and Asian data) did not experience any crimes in the past 12 months.

Unfortunately, victimization is not a rare event. For Europeans, the survey data yield a reported individual victimization rate of 9.6 percent; for North Americans the rate is 15.6 percent; and for Latin Americans it is 19.5 percent. For Africans, the reported household victimization rate is 36.5 percent; for Asians, it is 26.1 percent. These numbers may seem high, but they are similar to the results of reputable victimization surveys such as the International Crime Victimization Survey (van Dijk, van Kesteren, and Smit Reference van Dijk, van Kesteren and Smit2007), the British Crime Survey (Chaplin, Flatley, and Smith Reference Chaplin, Flatley and Smith2011), and the U.S. National Crime Victimization Survey (Truman and Rand Reference Truman and Rand2010). The regional barometers’ data on the demographic characteristics of crime victims are also consistent with existing research: In most places, young, single men living in cities are most likely to fall victim to crime (Gottfredson Reference Gottfredson1986; Kilpatrick and Acierno Reference Kilpatrick and Acierno2003). Table 2 provides a more detailed profile of crime victims in each region. The surveys do not contain any information about the suspected perpetrators of these crimes, but the majority of the offenses reported are nonviolent property crimes of the “petty” or “common” variety.

TABLE 2. Characteristics of Victims by Region

As explained in Table 3, the regional barometers also gather data on political participation and civic engagement, including: reported attendance at community meetings, political meetings, town meetings, and protests; frequency of conversations about politics, of attempts to convince others of political views, and of working with others to solve community problems; level of interest in politics; and leadership within community groups. These questions are used to construct nine separate dependent variables—a cumbersome but theoretically and methodologically justified move. Rather than privileging only “orthodox and approved forms of participation” (Baylis Reference Baylis, Booth and Seligson1978), this article strives to provide a comprehensive picture of citizens’ political involvement by including informal, community-based, and unconventional forms of political participation (Seligson and Booth Reference Seligson and Booth1976). Combining the different types of participation into an additive index would have attenuated the results if crime victimization had different consequences for different types of participation—which is entirely possible, because there may be different causal pathways to conventional and unconventional participation (Booth and Seligson Reference Booth, Seligson, Booth and Seligson1978)—and cherry-picking just one type of participation for the dependent variable would have produced unconvincing and potentially fragile results (Posner and Kramon Reference Posner and Kramon2011).

TABLE 3. Dependent Variables

Analysis and Results

This article estimates the individual-level relationship between reported crime victimization and political participation and engagement. Specifically, I test the hypothesis that individuals who report recent crime victimization will be more politically active and engaged than their peers. The most parsimonious regression model,

![\begin{eqnarray}

{\rm DV}_{\rm i} &=& \alpha + \beta {\rm Victim}_{\rm i} + \beta {\rm Male}_{\rm i} + \beta {\rm Age}_{\rm i} + \beta {\rm Age}_{\rm i} ^2 \nonumber\\[-2pt]

&&+\, \beta {\rm Econ}_{\rm i} + \beta {\rm Educ}_{\rm i} + \beta {\rm Urban}_{\rm i} \nonumber\\ [-2pt]

&&+\, \beta [{\rm CountryDummies}]_{\rm i} + \varepsilon _{\rm i} ,

\end{eqnarray}](https://static.cambridge.org/binary/version/id/urn:cambridge.org:id:binary:20160312035233457-0489:S0003055412000299_eqn1.gif?pub-status=live)

includes only the respondent's sex (Male), age in years (Age), age squared (Age2), socioeconomic status (Econ), education (Educ), and urbanization (Urban).Footnote 15 The model includes country fixed effects, with robust standard errors clustered at the lowest possible unit.Footnote 16

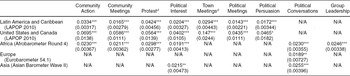

Table 4 reports the victimization coefficients from ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions for each region. In a strikingly consistent finding, the coefficients on victimization are all positive and statistically significant. No matter what the continent or the type of participation, having recently been the victim of a crime is always associated with greater political activity and engagement.Footnote 17 These results are robust to estimation with maximum likelihood estimators such as probit or ordered probit, as well as the inclusion of additional control variables.

TABLE 4. Crime Victimization Coefficients from the Main OLS Regressions by Region and Dependent Variable

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses; regressions estimated in Stata 10. All regressions include country fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered by municipality (Latin American and Caribbean), state/province (United States and Canada), district (Africa), region (Europe), and country (Asia). All models include key control variables: Male, Age, Age2, Econ, and Educ. All regressions except those with the U.S. and Canadian data also include the Urban control variable. The dependent variables have been rescaled so that 0 represents their minimum value and 1 represents their maximum value. Data from Lesotho are excluded because district was not recorded there. Data from Indonesia are excluded because Urban was not recorded there.

*p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

d Indicates dummy variable. Protest is a dummy variable in the LAPOP 2010 datasets. It is an ordinal variable with three values in the Afrobarometer Round 4 dataset.

Nearly all the coefficients in Table 4 are less than 0.05, but the magnitude of these results is far from trivial. In fact, crime victimization ranks among the most important predictors of political participation. The impact of crime victimization is generally equivalent to about 5–10 years of additional schooling, which is quite impressive, because education holds “the premier position among socioeconomic determinants of political activity” (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995).

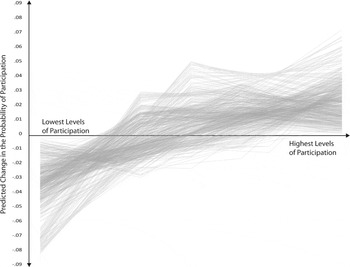

To illustrate the magnitude of the relationship between victimization and participation, all the core regressions reported in Table 4 are repeated with probit and ordered probit rather than OLS. Then Clarify (King, Tomz, and Wittenberg Reference King, Tomz and Wittenberg2000; Tomz, Wittenberg, and King Reference Tomz, Wittenberg and King2001) is used to estimate how an individual's levels of political participation and engagement are likely to change after he or she is the victim of a crime. While a particular gender and nationality are specified, all the other control variables are held constant at their means or medians. Then first differences are calculated by changing the value of Victim from 0 to 1, estimating, for example, the changes in the probabilities that an individual of a specific gender and nationality will have conversations about politics never, occasionally, or frequently. This procedure is repeated for every gender–nationality–dependent variable combination, which yields 624 first differences.

Victimization is always associated with decreases in the probability that an individual will have low levels of participation and engagement in politics, as well as increases in the probability that an individual will engage in high levels of political activity. Figure 1 summarizes these first differences. The graph contains 624 lines: one for each gender–nationality–dependent variable combination. For example, one line represents a Bolivian man and the frequency of his participation in protests; another line represents a Mongolian woman and her level of interest in politics. The X-axis measures the level of each type of political participation or engagement. Some of the dependent variables are binary, whereas others have three to five ordered levels, frequencies, or intensities. The lowest levels of participation are always on the extreme left of the X-axis, and the highest levels are on the extreme right. The Y-axis corresponds to the change in the predicted probability of each level of participation after a hypothetical individual's victimization status has been changed from 0 to 1. A positive value on the Y-axis indicates an increase in the probability of a given level of participation, and a negative value indicates a decrease in the probability of a given level of participation. To assist with comprehension of Figure 1, one of the lines is isolated and annotated in Figure 2.

FIGURE 1. Predicted Changes in the Probabilities of Different Levels of Participation following Simulated Victimization

FIGURE 2. Predicted Changes in Probabilities of Talking about Politics Never, Occasionally, and Frequently for a Senegalese Woman, following Simulated Victimization (Annotated to Facilitate Comprehension of Figure 1)

The lines in Figure 1 are transparent, so the darkest shading appears in areas where many lines overlap. Although the intermediate slopes of the lines vary, the crucial point is that the average slope of every single line is positive. That is, for every gender, every nationality, and every form of participation, crime victimization is associated with a decrease in the likelihood of the lowest levels of participation and an increase in the likelihood of the highest levels of participation. The extreme upper left and lower right quadrants of the graph are completely empty, with all the lines tracking from the lower left to the upper right.

The impact of victimization ranges from about 0.5 to 8 percentage points, depending on the gender, nationality, and dependent variable specified. The size of these results is typical of studies of political participation, which generally find effects of less than 10 percentage points.Footnote 18 This is true even of experimental interventions designed to stimulate participation: Get-out-the-vote phone calls can increase turnout by 3.8 percentage points (Nickerson Reference Nickerson2006), canvassing increases turnout by about 7–9 percentage points (Gerber and Green Reference Gerber and Green2000; Green, Gerber, and Nickerson Reference Green, Gerber and Nickerson2003), and different forms of social shaming increase turnout by about 2.5–8 percentage points (Gerber, Green, and Larimer Reference Gerber, Green and Larimer2008).

Furthermore, it is uncommon for individuals to participate in politics at the highest levels. So the relative impact of victimization is greater than it seems at first glance. For example, a typical Peruvian man who has not been the victim of a crime has a 0.043 probability of working with others to solve problems in his community every week. If that man is the victim of a crime, this probability is predicted to increase by 0.021, which translates to a 48.8% increase in his probability of working to solve community problems weekly. Crime victimization is generally associated with an increase of about 10–50% in the predicted probability that an individual will report the highest levels of participation or engagement. In a few instances, victimization nearly doubles the probability that an individual will participate in politics. The predicted probability that an average Canadian woman attended a protest in the last year is 0.027. When Clarify is used to change her victimization status from 0 to 1, the predicted probability increases to 0.051—an 89% jump.

Different Crimes, Same Results

All types of crime victimization are associated with higher levels of political participation, irrespective of the severity of the crime. The regional barometers all include some variables indicating what type of crime a victim experienced. The African and European data are the least detailed, whereas the Latin American data are the most fine-grained. The Asian data fall in between, measuring four categories of crime. In the U.S./Canadian data, there are very few victims of each type of crime, so it is not possible to analyze the relationship between types of crime and political participation in these two countries. For all the other datasets, however, it is possible to create a series of victimization dummy variables, one for each type of crime measured. Each new variable has a value of 1 for individuals who report that specific type of crime victimization and 0 for individuals who did not suffer any crimes in the past 12 months. Respondents who were the victims of another type of crime are dropped from the analysis.

To assess the relationship between different types of crime victimization and political participation, all the core regressions are repeated with these new binary variables used in place of the more general Victim variable. Afrobarometer asks respondents whether they or their family members have been the victims of two different types of crimes: theft from their houses or physical attacks. These questions are used to create two new binary variables measuring home burglaries and assaults. Because there are five dependent variables for the African data, this produces ten new regressions, all with the same specifications as described in Table 4. The resulting coefficients on home burglary are all positive, statistically significant at the p < .001 level, and within 0.002 of the victimization coefficients reported in Table 4. The coefficients on assault are positive, significant at the p < .001 level, and 0.006 to 0.023 larger than the corresponding coefficients reported in Table 4.

Eurobarometer asks respondents if they have suffered a break-in or theft at their homes in the past 12 months, or if they have been attacked or threatened. This yields two new dummy variables, which are used to run two new regressions evaluating the relationship between home burglaries, assaults/threats, and frequency of conversations about politics. The coefficients on home burglary and assaults/threats are both positive, significant at the p < .05 level, and about 0.002 larger than the victimization coefficients in Table 4.

Asian Barometer asks its respondents if they or their relatives have been the victims of four types of crimes in the past 12 months: theft of personal property, including pickpocketing; home break-ins or burglaries; physical violence; or theft of vehicles, including cars, motorcycles, bicycles, and—only in Mongolia—horses. When the Victim variable is replaced with these four new independent variables, the resulting coefficients on all four types of crime victimization are positive. Six out of the eight coefficients are significant at the p < .05 level, two at p < .01, and three at p < .001.Footnote 19 The coefficients on theft of personal property and vehicle theft are about 0.002 to 0.007 larger than the victimization coefficients reported in Table 4, and the coefficients on household burglary and violence are about 0.002 to 0.005 smaller.

Finally, using the Latin American data, seven new dummy variables are created, corresponding to each type of crime reported by at least 1% of respondents: unarmed robbery, unarmed robbery with assault or threats of violence, armed robbery, assault, vandalism or property damage, home burglary, and extortion. This generates 49 new regressions, which analyze the relationships between these seven types of crime victimization and the seven dependent variables in the Latin American dataset. The resulting coefficients on the victimization variables are all positive, with 18 coefficients significant at the p < .001 level, nine coefficients at the p < .01 level, nine coefficients at the p < .05 level, four coefficients nonsignificant with .05 < p < .1, and nine coefficients with p > .1.Footnote 20

Considered cumulatively, these results show a positive relationship between all types of crime victimization and all forms of political participation. There is no clear pattern with regard to the severity of the crimes. In the African and Latin American data, assaults have a particularly large impact, but in the Asian data, violence is one of the weakest predictors of political engagement. In the European data, assaults or threats and thefts have roughly the same impact. Furthermore, in addition to assaults, unarmed robberies and extortion have unusually large effects in the Latin American data. This suggests that the experience of victimization, rather than the aftereffects of violence or trauma, is responsible for this article's findings.

Summary of Results

Analysis of survey data from Latin America, North America, Africa, Europe, and Asia reveals a positive and statistically significant relationship between all forms of crime victimization and all forms of political participation and engagement. In all the major regions of the world, men and women who report that they were recently the victims of crimes are more active in civic and political life. This finding should not be aggregated to the group level, and it should not be assumed that all other types of violence—for example, political persecution—would produce the same effect. But despite these caveats, the identification of the relationship between crime victimization and participation represents an important advance in our understanding of the causes of political participation.

ADDRESSING THREATS TO CAUSAL INFERENCE

Individuals never choose to become the victims of crimes. Much like forced recruitment (Blattman Reference Blattman2009), crime victimization is exogenous and plausibly random conditional on individual and neighborhood characteristics (Demombynes Reference Demombynes2009). Nonetheless, this article addresses three threats to causal inference: reverse causation, neighborhood effects, and omitted variable bias. Three intractable issues are also highlighted: survey response bias, serial victimization, and subjective understandings of crime victimization.

Reverse Causation

If political activists are the targets of violence and intimidation, or if their activism puts them at greater risk of crime for some other reason, then being politically active could cause an individual to fall victim to a crime—not the other way around. To rule out the possibility of reverse causation, the optimal identification strategy would incorporate panel data,Footnote 21 an experiment,Footnote 22 or an instrumental variable.Footnote 23 Unfortunately, these methods are not feasible in this case, so the best realistic approach is (1) to control for previctimization levels of political participation; (2) to conduct a placebo test to check that recent crime victimization does not predict prior political participation; and (3) to control for political violence.

Controlling for Prior Political Participation

The crime victimization variables used in this article all reflect victimization within the past 12 months. So by controlling for the respondents’ involvement in politics more than 12 months before they were surveyed, it is possible to ensure that this article's findings are not merely a reflection of the respondents’ level of political participation before they were the victims of crimes. All the regional barometers include questions that can serve as proxies for previctimization participation. Eurobarometer asks respondents how often they have voted in European parliamentary elections, the most recent of which took place 16 months before the Eurobarometer 54.1 survey.Footnote 24 LAPOP, Afrobarometer, and Asian Barometer ask respondents if they voted in their countries’ most recent national elections. Excluding those countries that held elections in the 12 months prior to the surveys’ data collection periods,Footnote 25 this functions as an indicator of previctimization participation. When these new control variables are introduced into this article's main regressions, the relationship between victimization and participation remains positive and significant in all five regions, with victimization coefficients within 0.005 of those reported in Table 4 and p-values ranging from .000 to .044.Footnote 26

Two more tests confirm that previctimization participation is not driving this article's findings. First, to hold prior voting constant, the data are culled so that only individuals who report voting in the past are included in each dataset.Footnote 27 If past participation is causing both victimization and current participation, then the effect of victimization should disappear when the core regressions are repeated on the culled datasets. Quite to the contrary, across all five regions, the coefficients on victimization remain essentially unchanged: positive and, with two exceptions, statistically significant.Footnote 28

Second, matching is used to preprocess the data before repeating the article's main regressions (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Imai, King and Stuart2007a). For each of the regional barometer datasets, nearest-neighbor matching pairs reported victims with comparable nonvictims according to the variables Econ, Educ, Urban,Footnote 29 and Age, simultaneously requiring exact matches on gender, country, and voting history. Nonvictims who cannot be matched are discarded, ensuring that the reported voting histories of victims and nonvictims are completely balanced within the resulting datasets. Next, Zelig (Imai, King, and Lau Reference Imai, King and Lau2008, Reference Imai, King and Lau2009) is used to repeat the core regressions on the matched Latin American, North American, African, European, and Asian datasets. All the resulting coefficients on victimization remain positive and, with one exception,Footnote 30 statistically significant, the majority of them at the p < .001 level. This result, in combination with the two tests described above, is strong evidence there is a valid relationship between victimization and participation, irrespective of an individual's past level of political activity.

Placebo Test: Does Victimization Predict Prior Voting?

The questions about previctimization voting allow for a neat test of the causal order of the relationship between victimization and participation.Footnote 31 If this article's argument is correct, then recent crime victimization should be associated with higher levels of current participation in politics. Victimization should not, however, predict past voter turnout, because this would violate the basic logical intuition that causes must precede their effects (Mackie Reference Mackie1965). Prior voting can therefore be used as the dependent variable for a placebo test, as advocated by Sekhon (Reference Sekhon2009).

The placebo test consists of regressions with the following dependent variables: for the Latin American, North American, African, and Asian data, voting in the last national elections;Footnote 32 for the Asian data, the general frequency of prior voting; and for the European data, frequency of voting in past European parliamentary elections. Reported crime victimization within the past 12 months is the key independent variable, and all the regressions include the same control variables and specifications as described in Equation (1) and Table 4.

When the Latin American, Asian, and European data are used, victimization has no statistically significant relationship with past voting: The coefficients on victimization are very weakly positive, but they are dwarfed by their standard errors (p = 0.44, p = 0.42, and p = 0.98, respectively). Victimization has no relationship with the general voting history of the Asian respondents, either; though the coefficient is positive, its p-value is .91. The African data show that recent crime victimization is associated with a statistically significant decrease in the likelihood that an individual voted in the last national elections (coefficient = −0.023, p < .01). Encouragingly, these results suggest that victimization predicts current participation, but not past voting.

The placebo test does, however, raise questions about the relationship between crime victimization and political participation in the United States and Canada. When the dependent variable is prior voting, the coefficient on victimization is positive (0.061) and significant at the p < .01 level. This suggests that an omitted variable—most likely urbanization—is positively biasing the North American coefficients on victimization, which should be viewed as less robust than the other results reported here. At the same time, however, the placebo test should increase our confidence in the direction of the relationship between crime victimization and political participation in Latin America and the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa, Western Europe, and East and Southeast Asia.

Controlling for Political Violence

If crime victimization is associated with increased political participation because political activists are targeted for crime, then this relationship should be strongest in the most repressive countries. Yet a country's Freedom House score is not a statistically significant predictor of the average size of its victimization coefficients.Footnote 33 When average victimization coefficients are regressed on Freedom House scores, the resulting coefficient is very weakly positive and statistically nonsignificant (p = 0.82). Zimbabwe, China, and Vietnam have the worst Freedom House scores of the countries surveyed, but they are not among the countries where the largest effects of victimization are observed. Instead, the 20 countries with the highest average victimization coefficients include places like Canada (#1), the United States (#2), Austria (#8), Sweden (#9), Costa Rica (#11), and Japan (#17)—hardly bastions of political repression.Footnote 34

A further check exploits an Afrobarometer question asking respondents if they fear political violence. Logically, those who have previously been harmed because of their involvement in politics should be the most fearful of political violence, so this question can be used to create a new control variable that proxies for a history of politically motivated victimization. Repeating all the core regressions with the addition of this new control variable, the coefficients on victimization remain positive, statistically significant at the p < .001 level, and within 0.005 of the values reported in Table 4.

Although none of the tests described in this section can transform observational data into experimental data, they do indicate that the risk of reverse causation is low. The positive relationship between victimization and participation is robust to the inclusion of controls for previctimization political participation; victimization generally does not predict previctimization participation; the relationship between victimization and participation is positive and significant even in places where political repression is rare; and the coefficients on victimization remain unchanged when controlling for fear of political persecution. Reverse causation is, therefore, an implausible explanation for this article's findings.

Neighborhood Effects

Living in a high-crime area could cause an individual to be active in politics while also increasing his or her odds of crime victimization. This threat to inference can be mitigated by repeating the core Latin American, North American, African, European, and Asian regressions with controls for local and national crime rates. Separate regressions with the African and Latin American data also control for proximity to a police station and local gang activity, respectively. The results of all these regressions are substantively identical to those in Table 4: The coefficients on victimization always remain positive and statistically significant.

Nonetheless, unobservable neighborhood conditions are potential confounds that could influence an individual's risk of crime victimization (Bursik and Grasmick Reference Bursik and Grasmick1993; Van Wilsem, Wittebrood, and de Graaf Reference Van Wilsem, Wittebrood and de Graaf2006) and level of political participation. Demombynes (Reference Demombynes2009) deals with this problem by including locality fixed effects; this article goes further. Matching is used as preprocessing (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Imai, King and Stuart2007a) to cull the Latin American and African data so that victims are compared only with nonvictims from the same localities.Footnote 35 When the core Latin American and African regressions are repeated with these culled datasets, the results are nearly indistinguishable from those reported in Table 4. The victimization coefficients from the new regressions are all positive and significant at the p < .001 level, providing strong evidence that unobserved neighborhood effects are not responsible for the relationship between victimization and participation.

Finally, by considering the locations of the crimes experienced by the survey respondents, it is possible to confirm that undetected neighborhood factors are not causing both victimization and participation. LAPOP asks Latin American and Caribbean crime victims where they were victimized: in their homes, in their neighborhoods, elsewhere in their cities, or further afield. Dropping those individuals who were victims of crime in their homes or in their neighborhoods yields a new victimization variable. This dichotomous variable is coded 1 for individuals who were the victims of crimes outside their neighborhoods and 0 for individuals who were not the victims of any crimes anywhere. When the core regressions are repeated with this new independent variable, the coefficients on out-of-neighborhood victimization are all positive and significant at the p < .001 level.

Omitted Variables

Theories of “victim precipitation” and “victim proneness” suggest that crime victims’ personal attributes and lifestyles contribute to their victimization (for example, Hindelang, Gottfredson, and Garofalo Reference Hindelang, Gottfredson and Garofalo1978; von Hentig Reference von Hentig1948). This literature is rightly criticized for blaming victims (Elias Reference Elias1986; Stanko Reference Stanko, Hope and Sparks2000; Walklate Reference Walklate2007), but the mere possibility of victim precipitation demands special attention to any characteristics that could increase an individual's risk of crime while also making him or her more likely to participate in politics.

As described in Table 2, crime victims tend to be more educated and more urban than nonvictims. To rule out the possibility that an omitted variable related to education or urbanization could be causing the relationship between victimization and participation, all the core Latin American/Caribbean, North American, African, European, and Asian regressions are repeated with additional controls for wealth and education, plus numerous demographic characteristics that could be proxies for education or urbanization: race, religion, multiple measures of income, occupation, employment status, car ownership, computer ownership, computer usage, television ownership, cell phone usage, sewer service, electrical service, road quality, and frequency of going hungry. The coefficients on victimization are essentially unaffected by the addition of these new variables, remaining positive, statistically significant, and very close to the values reported in Table 4.

High levels of social activity, spending time with strangers, and being in public places—particularly at night—are generally thought to increase the likelihood of crime victimization (Gottfredson Reference Gottfredson1986; Hindelang, Gottfredson, and Garofalo Reference Hindelang, Gottfredson and Garofalo1978; Stanko Reference Stanko, Hope and Sparks2000). Sociable, extroverted individuals also gravitate toward participation in politics, particularly in activities that involve social contact (Gerber et al. Reference Gerber, Huber, Doherty, Raso and Ha2011; Mondak et al. Reference Mondak, Hibbing, Canache, Seligson and Anderson2010). To ensure that personality and daily routines are not omitted variables, additional controls are added to the Afrobarometer, Asian Barometer, and LAPOP regressions. The core African regressions are repeated with a new control variable measuring the frequency with which the respondents go on trips of 10 km or more, and the core Asian regressions are repeated with a new control variable measuring the number of people with whom the respondent interacts in a typical day. These new variables are proxies for the respondents’ levels of activity outside the home. In both sets of regressions, the coefficients on victimization always remain positive and significant.

The LAPOP surveys ask respondents to what degree they are a “quiet and shy person” and a “sociable and active person.” As expected, the most outgoing respondents participate in politics more than average and are also at slightly higher risk of crime victimization. But even controlling for shyness and sociability, the Latin American and North American coefficients on victimization are still positive and significant. The LAPOP 2008 surveys offer further evidence that personality and lifestyle are not biasing this article's conclusions. LAPOP 2008 asks Central American respondents if they have curtailed their shopping or recreational activities because of concerns about crime. Running this article's core regressions on this LAPOP 2008 data confirms that there is a positive, statistically significant relationship between recent crime victimization and all forms of political participation in that dataset. Next, the same core regressions are repeated two more times, using limiting shopping or recreation as the dependent variables. If crime victims are politically active because they are exceptionally sociable and outgoing, then they should not be reducing their leisure activities because of fear of crime. In both new regressions, however, the coefficients on crime victimization are positive—meaning that victims are more likely to limit their activities—and statistically significant at the p < .001 level. Recent crime victims decrease their shopping and recreational activities at the same time they increase their participation in politics. This suggests that personality is not the root cause of the relationship between victimization and participation.

Intractable Issues

Survey Response Bias

Some individuals may be so traumatized by their experiences with crime that they refuse to answer questions about crime or to participate in surveys (Zvekic and Alvazzi del Frate Reference Zvekic and del Frate1995). If these types of victims are excluded from the data analyzed here, this poses a serious problem. However, criminologists consider victimization surveys the most reliable source of data on crime rates and victims’ attitudes (Elias Reference Elias1986). Additionally, some researchers speculate that if any survey response bias exists, it may be because victims want to share their stories and are thus more likely than nonvictims to participate in surveys (van Dijk, Mayhew, and Killias Reference van Dijk, Mayhew and Killias1990). Either way, there is no indication that crime victims are over- or underrepresented in the regional barometer surveys; recall that these surveys’ victimization rates are in line with other published estimates.

The relationship between victimization and participation is also consistently positive whether the key independent variable is direct or indirect victimization and regardless of how the surveys were conducted (face-to-face versus telephone interviewing). LAPOP helpfully distinguishes between direct and indirect victimization, asking respondents from Latin America and North America if they personally were the victims of a crime in the past 12 months, and, in a separate question, if anyone else in their households was a victim in the past 12 months. Although individuals are surely upset when a relative is the victim of a crime, this indirect victimization is unlikely to leave them so traumatized that they would refuse to participate in a survey—particularly a telephone survey, which is how LAPOP is conducted in the United States and Canada. Yet even when only indirect victimization is considered, the coefficients on victimization are positive and statistically significant for both the Latin American and the North American datasets.

Serial Victimization

Individuals often fall victim to crimes because of ongoing social situations, relationships, and life circumstances, so serial victimization is common (Elias Reference Elias1986; Gottfredson Reference Gottfredson1986; Walklate Reference Walklate2007). If a survey respondent says that he or she was the victim of a crime in the past 12 months, then he or she has likely suffered other crimes before. The ubiquity of serial victimization means that it is impossible to know if the effect reported here is the short-term result of a stand-alone event or the cumulative impact of a lifetime of victimizations (Demombynes Reference Demombynes2009). Future researchers may want to conduct a long-term panel study to resolve this question.

Types and Understandings of Victimization

The decision to identify oneself as a victim of crime is influenced by both socialization and culture (Elias Reference Elias1986; Walklate Reference Walklate2007). Particularly across countries, survey respondents likely have different understandings of crime (Walklate Reference Walklate2007). All the regional barometers ask about specific, concrete types of crime, but it is still possible that some victims do not consider themselves to have been the victims of a “crime,” so their victimization goes unreported (Zvekic and Alvazzi del Frate Reference Zvekic and del Frate1995). Furthermore, like all victimization surveys, the regional barometers likely miss domestic violence, child abuse, elder abuse, and discrimination based on gender, sexual orientation, and race (Stanko Reference Stanko, Hope and Sparks2000), as well as corporate fraud and state violence (Walklate Reference Walklate2007). The relationship between these forms of victimization and political participation remains unknown.

IMPLICATIONS FOR DEMOCRACY

Across much of the developing world, the third and fourth waves of democratization have proceeded in tandem with crime waves (LaFree and Tseloni Reference LaFree and Tseloni2006), leaving new democracies in Latin America and Africa struggling to consolidate while confronting some of the highest violent crime rates in the world.Footnote 36 If falling victim to a crime can spur individuals to become more active in politics, what does this mean for these fragile democracies?

In light of Verba and Nie's (1972) maxim that more participation equals more democracy, one could argue that if crime victimization leads to increased participation in politics, then high crime rates should be good for democracy. There are two problems with this logic. First, this reasoning ignores the individual nature of the relationship identified in this article and conflates two different units of analysis. Drawing a conclusion about a group-level outcome on the basis of an individual-level result is an example of the individualistic fallacy.Footnote 37 Even if crime victims increase their participation in politics, high crime rates will not necessarily be associated with high rates of political participation at the aggregate level. As victims become more likely to attend political meetings or rallies, concern over rising crime rates may make their nonvictimized neighbors less likely to do so, resulting in a net decrease in participation. Consequently, this article makes no claims about the group-level relationship between crime rates and participation rates, though high crime rates are commonly thought to drive down participation.Footnote 38

Second, crime victims may develop authoritarian sympathies at the same time they become more politically active. In this case, crime-related increases in participation could undermine, rather than strengthen, new democracies. History suggests reason for concern; in interwar Europe, the democracies that collapsed had slightly higher crime rates than the democracies that survived (Bermeo Reference Bermeo1997). Writing about contemporary Latin America and Africa, Bitencourt (Reference Bitencourt, Tulchin and Ruthenburg2007), Kuenzi (Reference Kuenzi2006), Pérez (Reference Pérez2003), and Tulchin and Ruthenberg (Reference Tulchin, Ruthenburg, Tulchin and Ruthenburg2006) argue that high crime rates may increase support for authoritarianism. Carreras (n.d.), Fernandez and Kuenzi (Reference Fernandez and Kuenzi2010), and Malone (Reference Malone2010) extend this claim to the individual level, using survey data to demonstrate that recent crime victims tend to be disenchanted with their governments and the very notion of democracy, an idea also promulgated by Caldeira (Reference Caldeira, Jelin and Hershberg1996, Reference Caldeira2000). Cruz (Reference Cruz2000) further asserts that crime victims’ movements will be marked by fear, paranoia, and antidemocratic behavior such as social cleansing, which is consistent with prior research showing that crime victims are more supportive of vigilante justice (Briceño-León and Ávila Reference Briceño-León, Ávila and Carrión2002; Demombynes Reference Demombynes2009; Malone Reference Malone2010).

Using data from the regional barometers, I test three hypotheses derived from this literature: (1) crime victims will be more skeptical of the value of democracy; (2) crime victims will have more favorable opinions of military government and dictatorship; and (3) crime victims will be more likely to support vigilantism and harsh policing tactics. These regressions are based on Equation 1, using Victim as the key independent variable. The relevant political opinion variables are the dependent variables.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, recent victimization is strongly associated with rejection of democracy, support for authoritarianism, and approval of repressive policing and vigilantism.Footnote 39 Victims are more likely to say that high levels of crime could justify a coup (p < .001), and they are more favorably inclined toward authoritarian government (p < .001). They report less satisfaction with the way democracy works in their countries (p < .001), and they are less likely to prefer democracy over all other forms of government (p < .001), though there is no relationship between victimization and the belief that democracy is the best form of government. Victims are also far more likely to support vigilante justice (p < .001), mano dura or “iron fist” policing tactics (p < .001), and police action at the margin of the law (p < .001).

Beyond Latin America, the impact of victimization is more ambiguous. In the United States and Canada, crime victims’ opinions about democracy, authoritarian government, and vigilantism and policing tactics are generally indistinguishable from those of nonvictims, though victims are less likely to prefer democracy over all other forms of government (p < .05). In Africa, crime victimization has no statistically significant relationship with support for military rule, support for rule by one individual, or preferences for democracy over all other forms of government. African crime victims are less satisfied with the way democracy works in their countries (p <.001), but paradoxically they are also less supportive of one-party rule (p < .05).Footnote 40 In contrast to Fernandez and Kuenzi (Reference Fernandez and Kuenzi2010),Footnote 41 this article does not find any evidence of a consistent relationship between crime victimization and rejection of democracy in Africa.

The Eurobarometer 54.1 survey includes one question about satisfaction with democracy, but it does not touch on authoritarianism, policing, or vigilantism. When the core Eurobarometer regression is repeated with satisfaction with democracy as the dependent variable, the coefficient on victimization is negative and statistically significant at the p < .001 level. Surprisingly, the European results show that crime victimization can be associated with democratic discontent even in wealthy, established democracies with low crime rates and well-functioning criminal justice systems.

Finally, Asian Barometer asks about satisfaction with and preferences for democracy, as well as support for rule by a strong leader, rule by one party, and military rule. There are no questions specifically about vigilantism or policing, but Asian Barometer asks respondents to what extent they agree or disagree that “cruel criminals should be punished immediately without regard to time-consuming legal processes.” When Equation 1 is used to run regressions with these new dependent variables, the results are inconclusive. There is no statistically significant relationship between crime victimization and satisfaction with democracy, support for one-party rule or military rule, or approval of swift punishment for criminals. There is, however, a positive and statistically significant relationship between crime victimization and support for a strong leader. Asian crime victims are also significantly less likely to prefer democracy over all other forms of government.Footnote 42

In contrast to the relationship between crime victimization and political participation, the relationship between crime victimization and political attitudes varies substantially around the world. In Latin America and the Caribbean, there is strong evidence that crime victims are more likely than their peers to devalue democracy, to idolize authoritarian rule, and to embrace vigilantism and harsh policing tactics. European crime victims are also significantly less likely to be satisfied with their democracies. In the United States and Canada, however, there is little evidence that crime victimization has any effect on attitudes about democracy or policing. And in both Africa and Asia, there is some limited evidence that crime victims may have stronger authoritarian sympathies than their peers, but the results are far from consistent. Further research will also be needed to determine whether, and under what conditions, crime victims act on their anti-democratic attitudes, which will likely depend on the local political context (Barker Reference Barker2007) and their personal characteristics.Footnote 43

CONCLUSIONS

Contrary to the dominant assumption that crime victims withdraw from public life, individuals who report that they have recently suffered crimes participate in politics more than comparable nonvictims. This relationship is consistent for men and women across five continents, for all types of crimes, and for all types of participation. Post-traumatic growth theory and narrow personal interest cannot fully explain why victims would become active in politics, so this article proposes that victims may also turn to politics for a combination of emotional and expressive reasons. Disentangling these potential explanations will require further qualitative research, as will thoroughly understanding the consequences of victims’ participation for democracy.

This article makes three contributions. First, it identifies crime victimization as a robust and remarkably consistent predictor of political participation, meaningfully advancing our understanding of the causes of political participation. Second, these results demonstrate that the positive downstream consequences of victimization identified by Bellows and Miguel (Reference Bellows and Miguel2009), Blattman (Reference Blattman2009), Shewfelt (Reference Shewfelt2009), and Voors et al. (Reference Voors, Nillesen, Verwimp, Bulte, Lensink and van Soest2012) are not limited to survivors of civil wars or confined to specific countries. Third and most practically, the article provides a new lens for analyzing crime victims’ movements, which have played a significant role in politics around the world, from Argentina to the United States to Japan.Footnote 44

Because crime victimization is a common experience, it is important to understand its political consequences. But the basic insight that victimization can motivate participation may also have broader implications. For example, falling victim to serious natural disasters and diseases may spur individuals to increase their involvement in politics.Footnote 45 Although it would be wildly premature to say that all victims should be expected to increase their participation in politics, this article's results—in combination with the literature on wartime trauma, illnesses, and natural disasters—offer tantalizing hints of a potentially wide-reaching relationship between victimization and participation. This opens up exciting new avenues for investigation by quantitative and especially qualitative researchers. Which victims are most likely to participate in politics? When, where, and why do they participate? Are there any subcategories of victims who shy away from politics, bucking the general trend? What do victims achieve once they mobilize?

Answering these questions will add depth and nuance to the results reported here, while also heeding Jennings's (1999) call for greater attention to the role of pain and loss in politics. These emotions are often overlooked in political science, yet they can be powerful drivers of political action. Javier Sicilia's activism, for example, is deeply imbued with the rhetoric of pain. He explains,

In speaking openly about my pain, I've been speaking about the pain of all the families who have lost loved ones. Many who get caught up in the drugs violence are impoverished and powerless—they don't have the opportunity that I have, as a middle-class person who is quite well-known and connected, to speak out and be heard. That's why I feel I must do this—because I can be a voice, and the situation is now so bad that it demands action. (Quoted in Moorhead Reference Moorhead2011)

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.