Over the past fifty years, the number of international human rights codified in treaty form has exploded. There are now nine core multilateral human rights agreements, each with their own monitoring body, and several optional protocols.Footnote 1 This treaty regime covers a range of rights for all persons, from civil and political to economic, social, and cultural rights. Dedicated treaties aim to eliminate discrimination against racial minorities and women, and to protect the rights of children, migrants, and the disabled. Every country has committed itself to at least one of these core treaties, and most have ratified several.

The treaties are administered by reviewing bodies that, among other functions, receive reports from the member states on their human rights practices. Recent research has shown that reporting states improve their rights practices when they engage in ongoing dialogue with these treaty bodies, throwing into question earlier impressions that self-reporting is inconsequential. This improvement occurs even though states that report are initially no better at respecting human rights than those that do not.Footnote 2

To be sure, the human rights treaty body system has faced many challenges. Reform discussions have recurred since its inception.Footnote 3 Commentary has grown more urgent since the early 2000s, as the system has expanded in size, scope, and membership. In 2009, the UN high commissioner for human rights initiated a process to strengthen the treaty bodies, recognizing that chronic under-resourcing, backlog, lack of engagement, and complexity of working methods were compromising the system. After consultations with states parties, experts, and civil society, the high commissioner presented a report to the General Assembly proposing measures to reinforce the system.Footnote 4 Following two years of difficult negotiations among member states, the General Assembly adopted a resolution to do so.Footnote 5 This resulted in measures aimed to enhance the treaty bodies’ capacity to protect human rights. In 2020 the General Assembly will review these measures’ effectiveness and consider additional actions to further improve the system.

Given these upcoming reform discussions, it is important to understand the nature and quality of the self-reporting process and consider evidence-based recommendations for its improvement. Over the past decade, our understanding of international treaties’ effects on state behavior and human rights outcomes has grown significantly,Footnote 6 but few studies investigate systematically how self-reporting affects treaty implementation and ultimately domestic laws and practices. The most rigorous evidence to date establishes a plausible connection between the cumulative effects of participating in the reporting process and improved human rights outcomes. Recent research shows that the more frequently states participate in the reporting process, the better they perform on relevant indicators of rights outcomes.Footnote 7 In particular, repeated and cumulative dialogues with treaty bodies have contributed to lower levels of discrimination against women and physical integrity rights violations. Employing a range of statistical techniques, these studies help establish a causal connection between the fact of iterated reporting and improved rights practices and gesture toward mechanisms of public attention and political mobilization as potential explanations for this connection. However, research has yet to explore the range of theoretical mechanisms that plausibly account for the link between reporting and rights improvements. In short, the process connecting periodic review by the treaty bodies and human rights improvements remains opaque.

This Article demonstrates that certain features of the process of self-reporting to human rights treaty bodies can account for the positive relationship between the act of reporting and positive human rights outcomes reported in earlier research. In particular, this Article systematically documents—across treaties, countries, and years—four mechanisms that theory and evidence suggest contribute to human rights improvements: elite socialization, learning and capacity building, domestic mobilization, and law development. We show that reports are becoming more thorough, increasingly candid, and more relevant to treaty obligations. More states are developing the capacity to collect, systematize, and analyze information—and more are willing to include such information in their reports—than in the past. Most importantly, the report-and-review process seeps into domestic politics, as reflected in the growth and localization of civil society participation (shadow reporting) and local media publicity. In other words, what is discussed in Geneva does not stay in Geneva. It spills over into domestic debates, adding fuel to mobilization and prompting demands for implementation. The work of the treaty bodies is also increasingly relevant to and informs law development at the regional level.

This Article's claims are limited in two respects. First, it should be obvious that rights practices are shaped by many complex influences. No monocausal account of law—much less reporting under international treaty regimes—can fully determine actual rights protections and violations. The processes documented in this Article exist synergistically with a multitude of other influences; they do not operate in social, political, or legal isolation. Self-reporting matters because bureaucracies can learn, because the media reports, because groups mobilize, and because expert decisions and views contribute to law development. A host of other individuals and institutions—from special rapporteurs to local politicians—play important roles as well. The mechanisms discussed here benefit from, amplify, and empower these entities. Second, while the Article demonstrates that the reporting process accords with conditions that theoretically facilitate positive outcomes, causal tests for each mechanism are not presented here. Rather, we offer empirically supported reasons for taking seriously established causal claims between the act of self-reporting and positive human rights outcomes.

This Article first demonstrates in Part I that self-reporting is a crucial and pervasive “enforcement” device in both domestic and international law. Part II describes the history and evolution of the contemporary human rights self-reporting regime. Part III links self-reporting and review to theories of elite socialization, learning and capacity building, political mobilization, and law development. The conclusion in Part IV is cautiously optimistic. It entertains critiques, including potential problems of reporting fatigue and meaningless bureaucratic ritualization. It also offers policy recommendations based on theory and evidence. Far from conceding defeat, reforms should continue to focus on making the report-and-review process streamlined, accessible, and actionable.

I. Self-Reporting and Law “Enforcement”

Self-reporting has become a common tool of regulatory compliance at all levels of governance. At the national level, it is often considered the best—and sometimes the only—way to elicit information needed to enforce the law. From the U.S. Defense Department's Contractor Disclosure ProgramFootnote 8 to the Federal Energy Regulatory CommissionFootnote 9 to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,Footnote 10 American regulators routinely use self-reporting to enhance regulatory compliance and encourage the development of self-policing capacity among firms.

Self-reporting is also central to regional regulatory enforcement. The European Union depends on information provided by national administrations and employs “soft” tools such as regulatory transparency to encourage compliance with European policies.Footnote 11 The EU's Open Method of Coordination relies on iterative national reports to assess regulatory progress, provide peer review, exchange best practices, and occasionally issue recommendations on how best to achieve common regulatory goals.Footnote 12 A range of actors—national agencies, ministry officials, parliamentarians, civil society, and the media—deploy information disclosed during this process to set national policy agendas and press for reforms.Footnote 13

Critics debate self-reporting systems’ effectiveness in reducing law violations, but some domestic evidence suggests it is a useful component in a broader regulatory framework. Self-reporting systems have contributed to pollution abatementFootnote 14 by reducing the costs of monitoring,Footnote 15 encouraging remediation (or correction) of violations,Footnote 16 and generally contributing to a norm of “self-policing.”Footnote 17 Firms’ ability and willingness to self-police has long been an important aspect of deterrence and compliance in a range of regulatory arenas.Footnote 18

These systems also have well-known weaknesses. Often, actors resist self-reporting, especially when such requirements are new and perceived as burdensome. One particularly disparaged example is Section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act,Footnote 19 which required companies to disclose annually whether they had obtained certain minerals from mines controlled by armed groups in the Congo. Few reporting requirements have been so severely denounced as costly and ineffective. When some of the initial reports became available for review and analysis, they made for quite uninformative reading, with companies typically claiming they could not determine who controlled the mines from which they sourced minerals.Footnote 20

Yet even this much-maligned reporting requirement spawned potentially interesting dynamics. Some companies began to investigate the provenance of their mineral inputs, which incentivized implementation of firm governance models that increased the feasibility of tracing mineral sourcing. Models of supply chain due diligence were adopted to replace individual firms’ uninformative go-it-alone reports.Footnote 21 Third-party auditors developed a capacity to certify certain sources as “conflict free.” While early returns from the reporting were not encouraging, even-handed analysts noted new reputational pressures to scrutinize supply chains and concluded that the system should be improved rather than scrapped.Footnote 22 More importantly, firms were innovating even as they began—often reluctantly—the task of self-reporting. Some optimistic advocates attributed a decline in rebel mining in the Congo to greater attention by corporations and consumers to sourcing.Footnote 23

Domestic self-reporting systems for private or commercial actors, as well as regional European ones for governments, differ in an important respect from most international systems: they are usually backed by some ability to punish violators if detected. International regimes have very limited ability to punish delinquent non-reporters.Footnote 24 Instead, they must rely on moral suasion and peer pressure to encourage report submission. Governments might then face political pressure and administrators may even experience “lie aversion,”Footnote 25 which creates subtle pressures to be honest and thorough.Footnote 26

International law depends on self-reporting even more than domestic or regional legal systems do. International cooperation is inconceivable—or at least very inefficient—without the ability to collect and share credible information.Footnote 27 Such information makes it theoretically possible for states to avoid costly conflictFootnote 28 and realize joint gains that would otherwise be difficult to achieve given that “political market failures” are rife internationally.Footnote 29

In fact, self-reporting requirements are the most common form of “enforcement” in international law and institutions.Footnote 30 Barbara Koremenos recently found that a little over half of a random sample of treaties deposited with the United Nations rely on self-monitoring, third-party surveillance, or a combination of both.Footnote 31 In the area of arms control, some eighty-five of 227 agreements provide for self-reporting as the most intrusive form of monitoring.Footnote 32 When the stakes are high, self-reporting is often supplemented with verification by an international body, peer inspections, and/or unilateral or external monitoring. Under the Chemical Weapons Convention, for instance, states parties must initially declare stocks of chemical weapons and subsequent annual progress made toward their destruction.Footnote 33 The Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons verifies these declarations through onsite inspection. States parties may also request a “challenge inspection” of any other state party's facilities. Self-reporting thus plays a central role in arms control, even as verification provisions have increased and external monitoring has become denser.

Other areas of international law rely on self-reporting systems with weaker forms of delegated monitoring, while allowing for additional input from civil society, peer governments, and international bureaucracies. A good example is trade enforcement, which relies on a system of fire alarms rather than police patrols.Footnote 34 With private firms highly incentivized to report and litigate instances of noncompliance,Footnote 35 information is produced largely through dispute settlement.Footnote 36 However, the World Trade Organization (WTO) also collects information through regular “notifications” by governments regarding specific measures, policies, or laws. Regular reporting and review of trade policies also occurs through the Trade Policy Review Mechanism, with input provided by the reviewed state and the Organization's bureaucracy, followed by questioning by peer governments within a public forum.Footnote 37 In this case, the purpose is expressly not to enforce WTO law but rather to facilitate trade by providing transparency on members’ policies and practices.Footnote 38 While an innovation in monitoring multilateral trade agreements, practically nothing is known about its consequences.

Self-reporting is also a central pillar in international environmental agreements. Some, like the G20 Fossil Fuel Subsidy Agreement, depend almost exclusively on information from adhering states.Footnote 39 In many instances, self-reporting complements other forms of information gathering thought to be critical to transparency and ultimately compliance. For example, various “systems for implementation review” exist in international environmental agreements, “through which the parties share information, compare activities, review performance, handle noncompliance, and adjust commitments.”Footnote 40 While existing research does not theorize how state-generated self-reports can affect behavior,Footnote 41 the role of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) is likely a critical element. Many observers note the similarity between the watchdog role that NGOs play in supplementing state reporting in environmental and human rights implementation processes.Footnote 42

Monitoring provisions are also common in human rights agreements. In Koremenos's random sample, about 41 percent of human rights agreements contained no monitoring provisions at all, which is almost the exact proportion for international agreements as a whole (40 percent).Footnote 43 The remaining 59 percent of human rights agreements sampled are fairly “densely monitored” and commonly require states parties to report to “internal bodies” (e.g., treaty-based implementation committees) and establish a formal monitoring role for existing intergovernmental organizations (e.g., UN bodies) as well. For instance, since 2006, Universal Periodic Review has enhanced self-reporting to peers in the UN Human Rights Council. Overall, the international community depends heavily on states parties to provide the raw material for human rights oversight.Footnote 44

In issue areas from arms control to the environment, and from trade to human rights, state-generated information provision and review have been critical in increasing the transparency necessary for treaty implementation.Footnote 45 But has self-reporting enhanced international human rights treaty implementation? If so, how? It was certainly intended to do so, as the historical record discussed in the next part demonstrates.

II. Self-Reporting Under International Human Rights Law

Historical Development

Self-reporting is the tip of the spear of the accountability revolution in international human rights. Before World War I, there are only hints of such accountability in areas we might recognize as related to human rights. Reporting by states parties was discussed in the area of labor standards and in limited regional agreements to address what today we call human trafficking for sexual exploitation. As early as 1905, a draft labor convention called on national supervisory authorities to “publish regularly reports on the execution of the present convention and to exchange these reports among themselves.”Footnote 46

Two world wars changed global attitudes about state accountability, which was slowly built into inter-war international law and organizations. In November 1918, the League of Nations Committee on Labor urged governments to provide for the creation of an International Labor Office in the Paris Treaty of Peace. This office would be charged with the “collection and comparison of the measures taken to carry out international [labor] conventions and of the government reports on their observance.”Footnote 47 The next year, an American draft included reference to states parties reporting to the secretary-general of the League of Nations any actions taken in response to a “recommendation of the General Conference [of Labor] communicated to it.”Footnote 48 The International Labor Organization (ILO) constitution signed in 1919 ultimately required annual reports that “shall be made in such form and shall contain such particulars as the Governing Body may request.”Footnote 49

The Mandate System under the League of Nations also relied on reports from countries charged with overseeing non-self-governing territories, a practice continued under the Trusteeship Council of the United Nations.Footnote 50 Early human-trafficking conventions further signaled the emergence of reporting norms. Agreements negotiated in 1904 and 1910 to curb trafficking in prostitution had rudimentary information-exchange provisions,Footnote 51 and eventually came under the supervision of the League's Advisory Committee on the Traffic of Women and Children.Footnote 52 States began reporting to Geneva on anti-trafficking measures in the early 1920s,Footnote 53 and the 1926 Slavery Convention created an additional obligation to report relevant anti-trafficking laws to other parties and the League secretary-general,Footnote 54 though it failed to provide procedures for review or follow-up. In 1930, the British government tried to use the Permanent Mandates Commission model to gather information through reports to a “Permanent Slavery Organization,” but these efforts failed due to the financial constraints of the inter-war depression and the outbreak of World War II.Footnote 55 A more elaborated system for reporting and information sharing to counter human trafficking and other rights violations would have to await the postwar period.Footnote 56

The postwar international order crucially changed the context for human rights. Democratic governance was reestablished in many countries, including in the heart of Europe. Transnational organizations and faith-based organizations found their voices in advocating for human rights. Crumbling empires would be replaced by a wave of newly independent nation states. Many of these emerging states found common cause with rights advocates in their calls for national self-determination.Footnote 57

The postwar period was a watershed for both international human rights and for what has been called the “regulatory turn” in international law.Footnote 58 This regulatory turn undoubtedly fueled reporting as an enforcement mechanism, especially in international human rights law. Most basically, state reporting was a way for the United Nations to collect information for law development in the first place.Footnote 59 This role had been carried out on a limited basis under the League of Nations, but it became more common and widespread as human rights principles were codified in the early 1960s.Footnote 60 UN protocols increasingly called on states to submit information in the context of conciliation and dispute-settlement procedures.Footnote 61 Of central concern here, state reporting was employed first in general hortatory requests and then as a treaty obligation in an effort to secure adherence.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was the focus of these efforts. The UN General Assembly and Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) both passed resolutions requesting information on state law and practice on human rights. As early as 1947, the General Assembly recommended that the UN secretary-general request member states to report annually to ECOSOC, which would in turn report to the General Assembly on steps taken to give effect to “recommendations made by the General Assembly on matters falling within the Council's competence.”Footnote 62 This resolution was intended to include UDHR principles, which had no explicit provisions for implementation. Few states responded to such a general exhortation. ECOSOC thus postponed systematic review and instead perused the few reports it received on an ad hoc basis. Five years later, the submission of official state reports remained a rarity, so the Council discontinued this system of self-reporting entirely.Footnote 63

In 1956, ECOSOC again passed a resolution calling for systematic self-reporting on human rights.Footnote 64 It requested UN members to transmit reports every three years describing how they were implementing UDHR principles. John Humphrey, then serving as rapporteur of the International Committee on Human Rights, later reported that forty-one states (exactly half) responded as requested in the first round of reporting, and sixty-seven (over 80 percent) responded in the second round (1957–59). But Cold War rhetoric and a perfunctory review by the Human Rights Commission rendered the exercise ineffective.Footnote 65 Self-reporting received a boost six years later, when NGOs with consultative status in ECOSOC were invited to submit their views and observations to the Council.Footnote 66 The system of “shadow reporting” by civil society organizations was thereby conceived.

At best, the general call for reports on progress toward realizing the UDHR was a soft law obligation. The problem remained state cooperation. In 1965, ECOSOC invited states to participate in a three-year cycle of reporting on civil and political rights, economic and social rights, and freedom of information.Footnote 67 This process routed state reports through the Sub-Commission on the Prevention of Discrimination and the Protection of Minorities, which generally failed to read them—an outcome John Humphrey called “a political victory won by governments who do not favour the international enforcement of human rights.”Footnote 68 Rights advocates knew, however, they were not in a position to do much more than request state information. Despite his frustrations, Humphrey concluded that “[o]f the various techniques, reporting is the one with which the international community has had the most and probably the most successful experience” and that given government reticence to accept international oversight, “reporting may indeed, even for these rights, be the most practical means of implementation.”Footnote 69

The Consent-Based Treaty System

Self-reporting as part of a consent-based treaty obligation was another route to enhance implementation. This approach built on an explicit legal commitment and engaged expert implementation committees rather than government-composed bodies of the United Nations. As early as 1947, the Drafting Committee for the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) proposed a state reporting mechanism, to be triggered by UN General Assembly resolution, for “an explanation, certified by the highest legal authorities of the State concerned, as to the manner in which the law of that state gives effect to any of the said provisions of this Bill of Rights.”Footnote 70 The United States proposed amending this to regularized two-year intervals.Footnote 71 When the commission on human rights resumed discussion of the draft in 1950, the Soviet Union and its allies resisted the inclusion of any reporting procedures as contrary to Article 2.7 of the UN Charter, which prohibits the UN from intervening in matters essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state.Footnote 72 Resistance was due in part to the concern that while similar procedures were developing with respect to the drafting of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), that treaty was to be “progressively realized” while the ICCPR was “intended, in the main, to be applied immediately.”Footnote 73 Moreover, the idea of reporting on progress toward implementation might, some feared, undercut the idea that states should be in compliance with the ICCPR upon ratification.Footnote 74

To whom reports would be submitted was initially controversial as well. On the one hand, the idea of reporting to the General Assembly was anathema insofar as it meant that obligated states would in effect be reporting to those who remained outside the treaty arrangement.Footnote 75 On the other hand, some states objected to an autonomous body of individuals acting in their personal capacity as experts.Footnote 76 The former view prevailed, although the final draft acknowledged that the reports could also be forwarded to UN specialized agencies after consultation with the treaty body.Footnote 77

The Cold War effectively put the adoption of the ICCPR and ICESCR on ice between the tenth and twenty-first sessions of the Human Rights Commission (between 1954 and 1966). The Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), negotiated in the early 1960s and entering into force in 1965, turned out to be the path-breaking treaty that provided the model for nearly all major subsequent human rights agreements and established the precedent that human rights treaties must contain some means for implementation.Footnote 78 While CERD drafters could look to the (unadopted) drafts of the “international bill of rights,” the convention broke new ground as the first major post-UDHR treaty in force to require states to report to a treaty body. As such, the CERD provided an important model, especially for anti-discrimination treaties such as the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) negotiated a decade later.

Several historical streams converged in the late 1950s and early 1960s to elevate racial equality above “the sacred notions of sovereignty so closely guarded by many UN member states.”Footnote 79 The civil rights movement highlighted embarrassing conditions in the United States and created a sense of urgency surrounding the CERD.Footnote 80 Following the Holocaust, Israel pushed vocally for racial and religious tolerance. South African apartheid was also a focal point for the evils of extreme racial discrimination. But the decolonization movement itself provided the necessary condition for accelerating and strengthening international commitments to nondiscrimination based on race. It rapidly transformed the UN's composition, and the leadership of an Afro-Asian coalition spearheaded by Ghana, the Philippines, and others united the newly independent states.Footnote 81 In the Cold War context, decolonization also provoked the major powers to engage.

This global political context made possible consideration of binding legal obligations forbidding discrimination based on race. The CERD draft developed alongside the ICCPR and ICESCR, and as the first of the three to enter into force, it provided the model for implementation that would be replicated with only minor variations in subsequent agreements: a triad of petitioning, state-to-state complaints, and self-reporting to a treaty body. The first of these was optional and voluntary, as in every treaty to come. The second, while obligatory under CERD, is optional for all subsequent treaties and altogether absent from CEDAW. Moreover, it has scarcely been used. The third provided the minimum floor for treaty implementation. As the most broadly used component of the triad—and because of the institutional path dependence initiated by CERD—it is worth excavating the logics and interests expressed at its creation.

Debates over the CERD text reveal a keen sense of the limits of law alone to ensure compliance with international human rights obligations. Treaty drafters did not see public production of information as an alternative for international rule of law but as a complement. Delegates realized that racial attitudes were stubborn and would require treaty law, education, information, and supportive media and courts.Footnote 82 Self-reporting was considered a potentially powerful way to develop state capacity to prevent and punish racial discrimination. Some of the most powerful delegations were interested in pushing toward “fact-finding and reporting machinery … of the United Nations” so that members could be “helped to build up national institutions and national laws to give practical meaning to the principles endorsed by the draft Declaration.”Footnote 83

But what should CERD reporting obligations look like? Three models were debated.Footnote 84 In one, states would report in the context of quasi-judicial or conciliatory processes. In a second, reports would originate from civil society alleging treaty violations.Footnote 85 In a third, states would report regularly on their own implementation,Footnote 86 with Costa Rica drafting an amendment additionally inviting what are referred to today as civil society shadow reports.Footnote 87 Each mechanism had recognized weaknesses. State-based procedures were subject to politics, and their “effectiveness suffered accordingly.”Footnote 88 Critics argued that ad hoc individual complaints would not assure legislative implementation.Footnote 89 States reluctant to empower private actors in an international treaty criticized civil society initiation as unproductive.Footnote 90 Periodic state reports were considered “useful but … not enough, since they did not allow for intervention at the time when a violation took place.”Footnote 91

Self-reporting was an important supplement to other measures and commonly mentioned as “the bare minimum”Footnote 92 for implementing a serious human rights agreement. At least one state (Jamaica) emphasized the value of examination, review, and evaluation attendant to the obligation to report.Footnote 93 Ultimately, all three approaches were adopted in CERD: conciliation procedures were established,Footnote 94 periodic reporting was required by states,Footnote 95 and complaints by private individuals were permitted.Footnote 96 Despite concerns about redundancy associated with reporting for each individual treaty,Footnote 97 the three major multilateral human rights treaties of the 1960s—CERD, ICCPR, and ICESCR—each developed their own fairly similar implementation committees and reporting regimes.Footnote 98

After a lull in human rights codification, the international community turned to women's rights. Early treaties dealing with women's rights had practically no implementation provisions.Footnote 99 But by early 1967, the UN Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) began drafting a nonbinding Declaration on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, which was adopted by the General Assembly in November of that year.Footnote 100 ECOSOC and CSW worked on strategies for implementing the declaration over the next several years. In the hortatory tradition described earlier, one tactic was to ask states to submit voluntary reports on their implementation efforts, but this request elicited little cooperation.Footnote 101 By the mid-1970s, the CSW began working on a comprehensive and legally binding instrument, soliciting comments of governments and specialized agencies.

Self-reporting requirements were a central part of the discussions of the Working Group that drafted CEDAW. Although an early Soviet draft did not contain a reporting requirement, directing only that ECOSOC consider implementation periodically,Footnote 102 initial discussions revealed a willingness to include one, with most states considering the ILO, CERD, or ICCPR to be appropriate models.Footnote 103 The Netherlands called for civil society participation, “granting these organizations … a role in channelling [sic] wishes and complaints towards an international forum,” such as the CSW.Footnote 104 Canada suggested that all reporting go through the CSW to avoid “conflict in implementation procedures” across treaties.Footnote 105 Several countries anticipated the modern critique of reporting overlap, and called for simplification.Footnote 106 Women's groups were strongly behind reporting; in fact the draft article on state reporting was the only provision mentioned explicitly in a crucial 1976 statement by a broad coalition of women's NGOs sent to the Working Group.Footnote 107 In the end, Egypt, Nigeria, and Zaire's proposal to use language almost identical to that contained in the CERD was accepted.Footnote 108 A series of working groups finalized the agreement in 1979, and the CEDAW—with Article 18 describing the obligation to report on implementation—opened for signature the next year.

Current Practice and Recent Reforms

Today, each of the nine core international human rights conventions establishes an independent treaty body to monitor implementation.Footnote 109 These committees are comprised of ten to twenty-five independent experts nominated and elected by states parties for fixed, renewable terms of four years. By virtue of treaty ratification, states must submit periodic reports to each committee—ranging from every two to every five years—on the legislative, judicial, administrative, or other measures adopted to give effect to human rights obligations.Footnote 110 Periodic reporting has thus become an aspect of procedural compliance with a government's treaty obligations.Footnote 111 Niger submitted the first ever state report to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in January 1970. By 2017, the committees for the nine core treaties had received on average 129 state reports each year.Footnote 112

The treaty bodies largely employ the same general framework in examining reports. While not required, committees invite government delegations to Geneva to participate in an in-person consideration of the report.Footnote 113 A team of government officials appears before the treaty body for two or three three-hour discussions. Each review begins with the state's introductory statement followed by committee acknowledgement of the state's implementation progress. Rapporteurs are assigned to each country to provide a comprehensive overview of missing information, identify discrepancies between domestic and treaty law, point to previous recommendations on which they saw no progress, and request follow-up information on these recommendations.Footnote 114 Questions by other committee members follow. Sometimes state representatives answer on the spot; other times the government commits to follow up in writing. Committee members use this interaction to expound on what is normatively appropriate under the treaty. This so-called “constructive dialogue” provides an opportunity for mutual engagement, acknowledgment of progress made, and identification of areas for improvement.Footnote 115

Initially, the treaty bodies did not provide any collective assessment following their review. In 1980, the Human Rights Committee (ICCPR’s treaty body) extensively debated whether or how it should express comments on state reports. Most committee members favored committee reports, “conducted in such a way as not to turn the reporting procedure into contentious or inquisitory proceedings, but rather to provide valuable assistance to the State party concerned in the better implementation of the provisions of the Covenant.”Footnote 116 However, a minority supported the German Democratic Republic's view that the committee's primary function was not to “interfere … in the internal affairs of States parties,” but instead to merely include within its annual reports general comments addressed to all states parties.Footnote 117 A Soviet-coordinated bloc of members thus prevented treaty bodies from being able to pass judgment on the human rights situations in states throughout the 1980s.Footnote 118 This changed in the 1990s with the end of the Cold War. Now all committees publish some form of “concluding observations” containing recommendations for specific reforms a government should undertake to address implementation shortcomings.Footnote 119 Most commentators agree that these recommendations are not legally binding,Footnote 120 but all state reports and committee observations are made publicFootnote 121 and sometimes cited by domestic and regional courts,Footnote 122 arguably raising the political stakes of ignoring them.

These basic elements have remained essentially unchanged, although a few reforms have been introduced to help strengthen the treaty body system. The creation of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in 1993 was transformatory.Footnote 123 Before its creation, there was almost no capacity for human rights trainingFootnote 124 or strategic thinking on reform.Footnote 125 Far from just another example of an inflated UN bureaucracy, its establishment was a game changer that greatly improved the international community's capacity to make state reporting meaningful.

First, the OHCHR harmonized reporting guidelines across treaties, at the request of the General Assembly.Footnote 126 These include guidelines on a “common core document,” which provides background information, the general framework for the protection and promotion of human rights, and information on effective remedies. States need submit only one common core document to all treaty bodies, updating as necessary. This reduces reporting redundancy and encourages states to report periodically on treaty-specific information. The guidelines also limit the length of periodic reports.

Second, to improve the quality of the constructive dialogue, some committees began giving states a set of questions in advance of their report's review. They further expanded on this practice by making available a simplified procedure employing a “List of Issues Prior to Reporting” (LOIPR).Footnote 127 The state party's replies to the LOIPR count as its report for that treaty. In 2014, the General Assembly adopted a resolution that encouraged use of this simplified procedure across all treaty bodies.Footnote 128 It has since become standard practice to focus on these priorities, and the chairs of the treaty bodies—with the assistance of the OHCHR Secretariat—have made efforts to further harmonize their simplified procedure working methods in light of the 2020 treaty body review.Footnote 129 This includes recently agreeing to coordinate each treaty's list of issues for a given country, to reduce unnecessary overlap.

Third, the OHCHR invested in developing state capacities.Footnote 130 In 2015, the OHCHR enhanced regional training and workshops on state reporting, and developed a Practical Guide for reporting and follow-up in 2016.Footnote 131 The OHCHR further encouraged the establishment of dedicated national mechanisms to coordinate reporting and follow-up across national institutions and civil society.Footnote 132

Finally, the OHCHR took a leading role in providing support to a range of stakeholders, so that they might better engage with the periodic review process. It works closely with national human rights institutions (NHRIs) to support their interaction with the treaty bodies and civil society organizations.Footnote 133 A number of NHRIs now hold national consultations on report preparation or otherwise provide input to the state report; several submit alternative reports and/or provide oral briefings to the treaty bodies, either prior to or during the constructive dialogue.Footnote 134 The OHCHR also encourages civil society participation by providing treaty-specific guidelines for submitting shadow reports and attending sessions.Footnote 135

Assessments of Self-Reporting

How effective has this system of self-reporting been over the past half century? Although positive assessments are hard to find, a few authors note that self-reporting can, under some circumstances, have positive effects. Sally Engle Merry finds in her study of gender violence that NGOs have used the CEDAW Committee's concluding remarks to pressure governments to protect women from violence.Footnote 136 Xinyuan Dai reports positively on the informational role that independent NGOs play in the monitoring process.Footnote 137 A study by C.H. Heyns and Frans Viljoen mentions several committee observations and recommendations that have been flagrantly ignored, but lists others that have been heeded, such as the release of prisoners in Egypt, the disbanding of armed civilian groups in Colombia, and attention to minority cultural rights in Estonia.Footnote 138 Positive accounts typically stress that the influence of this process is diffuse and indirect, with the media, NGOs, domestic actors, and other governments using the committees’ concluding observations to pressure governments for change.Footnote 139

Much more common are criticisms of the system as inadequate, ineffective, and even “in crisis.”Footnote 140 Many governments fail to report altogether.Footnote 141 Reports vary considerably across countries and over time in their structure and quality.Footnote 142 Some commentators suggest that reporting varies by treaty as well: it may be easier to engage with obligations under CEDAW and CRC rather than on torture and civil rights.Footnote 143 States often provide inconsistent and meaningless data in their reports, making it hard to assess implementation.Footnote 144 Quality reporting requires expertise in and familiarity with the treaty and the reporting process, which many states apparently lack. And of course, capacity is not the only issue. Some states simply refuse to render self-critical reports,Footnote 145 and even resource-rich democratic states do not always do what experts tell them they should do.Footnote 146

Government commitment and state capacity both tend to contribute to compliance with reporting requirements. Gross domestic product per capita is strongly associated with the likelihood of reporting, suggesting that wealthier states are better able to bear the costs of compiling legislation, collecting data, and studying outcomes. For some treaties (such as CAT and CRC) bureaucratic capacity (in the form of an NHRI) also correlates with report submission as well as reporting quality.Footnote 147 NHRIs supply for many states the institutional capacity needed to provide factual knowledge of, expertise in, and familiarity with the treaty regime and reporting process.Footnote 148 Two other factors also correlate with better reporting: commitment to human rights law (widespread human rights treaty ratification) and regional reporting norms and socialization (the higher the regional reporting density, the more likely a state from that same region will report). States with the resources and a broad legal commitment to international human rights treaties are much more likely to turn in their reports than are poor states and spotty ratifiers. It is, however, not the case that nondemocratic countries or those with poor human rights records systematically avoid reporting.Footnote 149

Much of the criticism leveled at the self-reporting process focuses on the oversight machinery itself.Footnote 150 Bias and politicization of the process is a common concern. By 2000, almost half of the elected treaty body members had been government employees.Footnote 151 It is easy to find disparaging accounts of some committee members’ commitment to the task at hand,Footnote 152 and other members’ ritualistic commentary and superficial questioning.Footnote 153 Cultural insensitivity further reduces genuine dialogue and leads to formalistic recommendations that many states are unlikely to take up.Footnote 154 In addition, some governments complain the treaty bodies have overreached, assuming “additional responsibilities not envisaged in the … treaties.”Footnote 155

The oversight machinery is severely under-resourced, leading to a host of inadequacies. Committee members are not paid and often employed by governments or other institutions with the potential to compromise independence. They are swamped with work and sometimes take more than a year to respond to state reports.Footnote 156 Despite this, over the past two years the General Assembly adopted budget cuts that significantly impacted the treaty body system, which now faces a serious financial crisis and at one point the possibility of cancelled meetings in order to cut costs.Footnote 157 The capacity to follow up in practice on their recommendations is also severely limited.Footnote 158 While the OHCHR Secretariat and treaty body chairs have recently made efforts to harmonize and strengthen the follow-up procedure for urgent recommendations, the CRC Committee has discontinued follow-up due to resource constraints.Footnote 159 Repeatedly, the individual committees miss opportunities to work across institutions, such as when economic, social, and cultural rights are violated during periods of transitional justice.Footnote 160

Once concluding observations are rendered, there is little consensus on their impact. Several studies discuss their influence, but it is hard to tell whether the glass is half empty or half full, what criteria authors use to determine effectiveness, and whether the committees’ observations play any causal role.Footnote 161 Most literature on the treaty bodies is descriptive, and while many observers move readily from description to critique and policy recommendations,Footnote 162 it is difficult to infer what contribution the process has made to rights on the ground. Critics assert that those most affected by treaty violations are not even aware of the periodic review process. Hafner-Burton summarizes an informal (and untested) consensus among commentators that “the reports often don't seem to lead to results that matter.”Footnote 163

Despite these critical assessments, recent cross-national studies have found a correlation between reporting and better rights outcomes.Footnote 164 How might this be explained? The next Part theorizes the mechanisms through which self-reporting might lead to improvements.

III. Mechanisms for Human Rights Improvement

“Self-reporting” is a much more complex system than the name implies. It is not synonymous with whitewashed documents that receive brief acknowledgement in Geneva and then never see the light of day. Every step of this process creates opportunities for impact (and potentially backlash). Reviewing laws and collecting new data involve activating a domestic bureaucracy. Actors who otherwise might not have the chance to form coalitions, alter the policy agenda, or provide different versions of the status of treaty implementation are at least minimally empowered. The reporting process also offers external experts an opportunity to teach about international obligations, produce actionable recommendations, and learn about constraints experienced and resistance encountered. While not a panacea for protecting human rights, self-reporting is an opportunity to persuade, learn, build capacity, mobilize politically, and contribute to transnational law development. It is a crucial part of a broader system of human rights accountability.

Global correlations linking participation in the report-and-review process with rights improvements exist, notably for CEDAW and CAT.Footnote 165 But a theoretical account of the mechanisms underpinning these correlations is needed. Where feasible, we present global evidence to demonstrate the plausibility of these mechanisms for four treaty regimes: ICCPR, CEDAW, CAT, and CRC.

We limit our focus to these four treaties for a number of reasons. These represent some of the most important multilateral human rights treaties, covering a broad range of universal as well as group-specific rights. Yet they also vary in ways that permit examination of the self-reporting process in distinct contexts. Each entered into force at different historical moments but all have been in force long enough for significant state reporting histories to accumulate. In particular, the ICCPR—one of the conventions comprising the “international bill of rights”—enables evaluation over four decades and a broad range of rights. The other three represent “single issue” conventions situated within a broader regime organized around their respective issues, ones that often stimulate specialized interest group attention.Footnote 166 The CAT covers protections that touch on issues tied to national security and crime control (i.e., prisons and policing) and thus represents a hard case for the reporting process to influence policymakers. The CEDAW also represents a hard case in that it touches on culturally sensitive issues, but has a somewhat unique institutional history with a dedicated bureaucracy—now UN Women, the Secretariat of the Commission on the Status of Women—and active involvement by organized women's rights NGOs. It is also the second most widely ratified international human rights instrument, behind the CRC, which is ratified by every member of the United Nations save the United States. Like CEDAW, the CRC also touches on sensitive public/private sphere issues and mobilizes highly organized children's rights NGOs.

The analysis is limited temporally given the data demands to make a persuasive case, with a cut-off date of December 2011 for CAT and December 2014 for ICCPR, CEDAW, and CRC (see Online Appendix A for a description of the data collection process, coverage, and coding procedureFootnote 167). This precludes discussion of the self-reporting process in light of recent critiques of the treaty body system and its budgetary crisis, but the conclusion offers thoughts on implications for the current political moment.

Since self-reporting processes are complex and contextual, at times the empirical focus is limited to one region—Latin America. There are both practical and theoretical reasons for this choice. In practical terms, states in this region have in fact ratified the relevant conventions. Many were early parties and have committed to multiple agreements, providing a rich source of data. This contrasts with other regions, notably Asia and the Middle East, where governments have been more hesitant to ratify or have tended to do so with very broad reservations. While reservations do not preclude inclusion, ratification is a necessary condition for investigating the power of the report-and-review process. Further, Latin America is linguistically accessible, which allows for a deeper and more consistent qualitative examination of the posited mechanisms compared to a sampling of more countries with higher linguistic barriers. Tradeoffs are unavoidable; we have chosen to probe more deeply within a limited set of documents rather than attempt a broader but more superficial treatment.

Latin America is also a theoretically appropriate sample for a number of reasons. Human rights violations historically have been a serious issue in Latin America and reporting has varied across countries, by treaty, and over time. This is by no means an “easy” region for demonstrating the plausible influence of self-reporting processes on outcomes. Nevertheless, the conditions for such influence seem present: there is at least a modicum of elite acceptance of and integration into international legal institutions. With relatively democratic institutions, active civil society, and (to varying degrees) meaningful press freedom, states across Latin America are plausible candidates to investigate the potential impact of the periodic review process on rights protections.

Elite Socialization

Socialization is the process through which people adopt the norms, values, attitudes, and behaviors that a group accepts and practices. It involves cognitive elements, such as mechanisms of persuasion that change actors’ minds about facts, values, or norms; it also entails social influences, akin to peer pressure associated with the desire for social acceptance, which leverages praise, opprobrium, and other intangible rewards and punishments.Footnote 168 In the context of periodic review, elite socialization refers to the process through which officials participating in the preparation, presentation, discussion, and follow-up associated with reporting come to understand what the international community (represented by committee experts) means by implementation of and compliance with treaty obligations. Socialization suggests that government officials may seek to gain this community's acceptance and respect by demonstrating pro-social behaviors in words and actions. As such—and in contrast to learning, discussed below—socialization is an inherently intersubjective process. It depends on the interaction of the individual and the reference group, and denotes the process through which the former comes to adopt the norms and values of the latter.

Socialization theory assumes that elites are open to persuasion and/or peer pressure to conform to international standards. This seems plausible in the treaty-monitoring context. Participating in the constructive dialogue is consent-based, suggesting that no participant has a serious issue with the treaty body's authority to undertake its review. States parties elect committee members purported to be independent experts of high moral character, who psychological studies find are viewed as more credible and under many circumstances more persuasive than non-experts.Footnote 169 The perceived authoritativeness may thus imbue expert committees with normative power to persuade.Footnote 170 Social psychological research also suggests that persuasive attempts are more likely to be effective when conveyed in person rather than virtually or at a distance.Footnote 171 As an in-person and iterative process, government officials participating in periodic review are likely to find themselves in regular conversation with the committees, reinforcing socialization efforts and effects. At the very least, reporting generates discussion about treaty obligations’ meaning—an integral part of the compliance process.Footnote 172

Criticism, disapproval, and even moderate shaming are also integral to socialization. These social cues alter the costs associated with disapproved behaviors, social psychological costs that socialization theories emphasize involve a desire for group acceptance.Footnote 173 The treaty bodies aim to avoid aggressive and overt “naming and shaming” approaches in favor of tempered disapproval and constructive dialogue.Footnote 174 Felice Gaer (who currently sits on the Committee Against Torture) notes the advantages of a “dialogue” over a “confrontation,” and that dialogue has generated better outcomes than the more confrontational approach of the former Human Rights Commission.Footnote 175 To be sure, treaty bodies are clear about areas where states fall short and have failed to make progress. Such clarity furthers “[t]he very process of identifying, describing, and controlling human rights practices [which] helps the diffusion of the human rights discourse through global and local levels.”Footnote 176 Committee reviews are made public, which not only diffuses compliance norms but potentially influences officials’ reputations as well.Footnote 177 Even if initial participation in the report-and-review process is motivated by rote adoption of superficial “scripts of modernity,” it exposes governments to broader acculturation pressures for implementation and compliance.Footnote 178

Are government officials socialized to the reporting process and to international human rights norms more generally? Evidence can be found in the communicative process, in the form of (1) committee language consistent with socialization (praise and opprobrium in service of clear implementation standards), and (2) target engagement suggestive of increasing government understanding of the rules, norms, and purposes of reporting. The first implies that the committees communicate in a way that is plausibly persuasive; the second implies that the reporter communicates back: “I get it.” Empirically, we look for persuasive tone and language from committee members and higher quality, more thorough, and responsive reports from states over time.

Committees’ Communicative Choices: Preparing the Conditions for Socialization

Research on social persuasion suggests that language matters, and that persuasive communication must walk a fine line between normative clarity on the one hand and threatening or condescending language on the other.Footnote 179 Cultivating trust also has a significant impact on the prospects for persuasion.Footnote 180 While we do not have irrefutable causal proof that government elites have in fact become socialized by the periodic review process, we do demonstrate that the process displays theoretically necessary preconditions for socialization to occur and that it is thus conducive to that end.

If committees are communicating in order to socialize, we would expect them to frame comments using respectful language, in order to elicit genuine consideration of their suggestions. To maximize the possibilities for persuasion, we should see committee members keeping discussions professional, as research consistently shows that perceived expertise is positively associated with persuasion.Footnote 181 We would further expect that committee language stresses normative clarity, and evinces both back-patting and mild forms of criticism. To find evidence of socialization efforts, we examined in detail the history of committees’ communicative choices during constructive dialogues with five Latin American countries (Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Uruguay) across the four core treaties on which this Article focuses (ICCPR, CEDAW, CAT, and CRC).

In the early years of the treaty body system, committee members used formal, diplomatic, and often deferential language, particularly when discussing obligations that implicate national security or core societal norms and values. For example, during the Cold War the Human Rights Committee was rarely explicitly critical. It was not “uncommon for certain states, regardless of their human rights record, to be treated with ‘kid gloves.’”Footnote 182 Members typically elaborated on the scope and interpretation of specific covenant provisions (cuing their expertise) and then requested further clarification about legislation to indirectly highlight where there might be inconsistencies with ICCPR provisions (mild shaming).Footnote 183 The committee's deft requests in 1980 for clarification of Colombia's law and practices prior to cautiously worded suggestions provide one example.Footnote 184 There were undoubtedly exceptions in the early years, particularly for Latin American countries with military regimes or states of emergency. Stressing normative clarity, committee members could be quite blunt when they thought there was a significant gap between a state's laws and international norms.Footnote 185

The diplomatic and indirect approach began to shift in the late 1980s, with committee members much more willing to identify directly inconsistencies between domestic law and treaty obligations. Over the 1990s, members increasingly drew attention to insufficient legal implementation. For instance, the CAT country rapporteur for Uruguay's second review explicitly stated that the Penal Code's two-year sentence for abuse of authority was “insufficient” in light of Article 2 of the convention.Footnote 186 Another member noted an additional “contradiction” between the Penal Code's inclusion of a due obedience defense and convention obligations and asked the delegation to “express its views on that contradiction.”Footnote 187 Members were sometimes loath to explicitly identify violations in practice, but a few began to do so, often avoiding direct accusations by drawing attention to alleged incidents of non-compliance from NGO or U.S. State Department accounts and asking the representative to comment on them. Allegations of torture incidents in Argentina followed this pattern,Footnote 188 followed by solicitous back-patting for the country's commitment to preventing torture and improvements in other areas.Footnote 189 This is evidence of the committees’ efforts to influence behavior through balanced concern and praise, while articulating what counts as compliance with treaty obligations. Prompting government agents to reflect and comment on implementation shortcomings represents a practice of “cuing,” a central tactic of persuasion.Footnote 190

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, a few committees grew increasingly confrontational, adopting tones that belied the notion of dialogue or persuasion. Confrontation tempered somewhat by the early 2010s, when the character of committee dialogues became less accusatory and much more technical. States predominantly provided objective descriptions of laws, policies, and practices, and committee members underscored their expertise with near clinical assessments of (in)compatibility with treaty provisions, followed by detailed questions to point to shortcomings or to clarify the situation. Committee members frequently draw from reports by NGOs, the U.S. State Department, special procedures, regional human rights mechanisms, and other treaty bodies’ concluding observations to flag discrepancies with the state's report and request clarification or comment.Footnote 191

Consistent with socialization theory, members telegraph their meaning using cooperative and problem-solving language, sometimes following up critical assessments (mild shaming) with assurances that we are here to help (identification and back-patting), and offering new or alternative approaches to address recognized shortcomings.Footnote 192 During Chile's most recent CEDAW review, Patricia Schultz (Switzerland) commended the creation of the Technical Secretariat for Gender Equality and Non-discrimination before noting that “action currently being taken to guarantee equal access to justice and protection against gender stereotyping remained either insufficient or insufficiently timely,” and suggesting that the Committee's General Comment No. 3 “could provide useful guidance for addressing that situation.”Footnote 193 A CAT Committee member expressed alarm at the large number of individuals in pre-trial detention in Colombia, stressing that the problem needed to be addressed “urgently and imaginatively,” employing alternatives to detention such as electronic bracelets and community service.Footnote 194 In discussing Mexico's new legislative efforts on detention registers, another CAT Committee member suggested that legislation include “robust mechanisms, such as the use of video recordings and Global Positioning System (GPS) equipment, to guard against the falsification of information.”Footnote 195

The normative strategy remains central: the word “should” appears frequently both during the dialogue and within the concluding observations. To be sure, questioning remains demanding and occasionally sharply critical. For example, Olivier de Frouville (France) began the second session of Colombia's most recent review before the Human Rights Committee by noting that “the vagueness and evasiveness of the [delegation's] replies … were making it difficult to engage in a truly constructive dialogue” and that the information provided by the government “shed relatively little light on the state of implementation of the Covenant on the ground.”Footnote 196 A CAT Committee member characterized Argentina's recent proposed amendments to its criminal sentence enforcement legislation as making “a mockery of the notion, enshrined in the Constitution, that serving a sentence was a form of rehabilitation.”Footnote 197 Overall, however, there appears to have been a clear shift to less politicized language by the 2010s, in line with many theories of persuasive communication. Of course there is room for improvement: a number of government comments in the context of the 2020 treaty body review note that the current process seems more like a “‘one-way dialogue’ that resembled an appearance before a court”Footnote 198 than a genuine dialogue, leading to a “frustrated feeling of not having been heard.”Footnote 199 Such experiences may hamper elite socialization, a point to which we return in the conclusion.

Socialization in Practice: Taking Reporting Seriously?

Have states become socialized to take their procedural obligations under treaties seriously? Treaty bodies have set a public normative expectation that governments submit timely, responsive, and transparent reports. Committees repeatedly and vigorously praise quality reports and express disappointment at delayed submissions or reports that fail to conform to guidelines.Footnote 200 This is how social norms are created and transmitted.

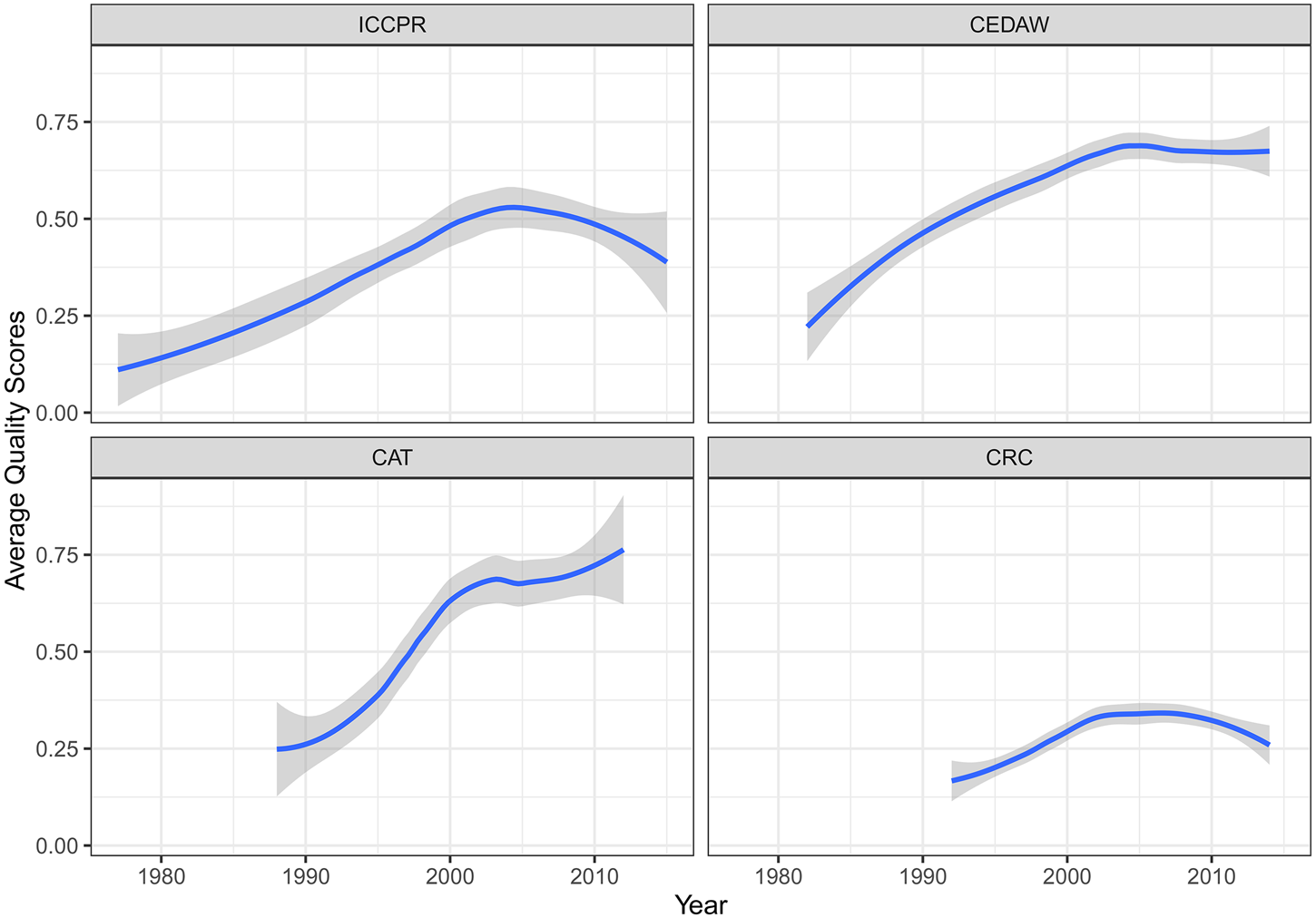

To find out whether states have become socialized into these reporting expectations, we read all state reports (not just those for Latin America) submitted under four core human rights treaties—ICCPR, CEDAW, CAT, and CRC. Each was assigned a quality score, based on the government's willingness to recognize shortcomings in implementation or compliance and to outline specific measures or efforts to address them (see Online Appendix A for the coding procedure). Figure 1 shows the average quality scores for reports submitted under each treaty over time. Improvements in report quality vary noticeably across treaties. The earliest reports were not forthcoming in acknowledging shortcomings, but with the partial exception of CRC and ICCPR reports in more recent years, they systematically improve in candor and transparency over time.

Figure 1. Average report quality scores across four core human rights treaties. Average quality scores assigned to all reports in a given year as a proportion of the total score a report could receive (0–1). Report quality scores available for: ICCPR (1977–2014); CEDAW (1982–2014); CAT (1988–2011); and CRC (1992–2014). Grey shading denotes 95% confidence intervals. See Online Appendix A for details on the coding instrument and procedure.Footnote *

Elite socialization also implies that governments become increasingly responsive to committee concerns. To evaluate this expectation, we assigned all reports (except initial reports) submitted under the same four core human rights treaties a responsiveness score, based on how well the report engaged with the committee's previous concluding observations (see Online Appendix A for the coding procedure). Figure 2 shows state reports have become more responsive to committee recommendations and concerns over time, though ICCPR reports tend to be relatively less so than those under the other three treaties. This shift was reinforced in the 2010s by the institutional reform of moving to the simplified reporting procedure.Footnote 201 Steady improvements in responsiveness provide indirect evidence that elite socialization to international norms is at work.

Figure 2. Average report responsiveness scores across four core human rights treaties. Average responsiveness scores are assigned to all subsequent reports in a given year as a proportion of the total score a report could receive (0–1). Report responsiveness scores available for: ICCPR (1978–2014); CEDAW (1991–2014); CAT (1992–2011); CRC (1997–2014). Grey shading denotes 95% confidence intervals. See Online Appendix A for details on the coding instrument and procedure.Footnote *

Finally, we expect governments to genuinely deliberate during the constructive dialogue. Evidence points to language of both deliberative engagement as well as resistance during these reviews. Examples of genuine engagement include Uruguay's explicit recognition that it needed to align its legal system with the CAT and its openness to the committee's recommendations for how to do so.Footnote 202 Similarly, Argentina told the Committee Against Torture that it considered its definition of torture “sufficiently broad to cover the requirements of the Convention” but that “it remained open to suggestions from the Committee in that regard.”Footnote 203 Before the Committee on the Rights of the Child, an Argentine delegation “did not deny that … domestic legislation ran counter to some of the recommendations set forth by the Committee,” then reminded the committee of recent developments in case law.Footnote 204 Mexico accepted a CEDAW Committee member's observation that a discriminatory culture in the government remained a primary obstacle to gender equality in politics, and committed to develop programs to help promote women at all levels of government.Footnote 205 More recently, the Mexican delegation acknowledged the same committee's concern that “much remained to be done to improve conditions for women in detention.”Footnote 206

Clearly, states resist as well, particularly regarding matters that touch on national security or core societal norms and values. An Argentine representative resisted a suggestion to review the government's criminalization of abortion.Footnote 207 Chilean representatives were particularly defensive during the military government's first review by the Human Rights Committee, noting that “some members of the Committee had made highly politicized statements which had been repeated many times in other forums.”Footnote 208 Such a statement demonstrates the limits of politicized shaming in this setting; the committees themselves have returned to more professionalized assessments.

We can draw several conclusions from this exploration of the reporting process. First, it is a process in which elite socialization—the gradual adoption of the norms, values, attitudes, and behaviors accepted and practiced by a group—is possible.Footnote 209 Since confrontation and harsh excoriation are likely to lead to backlash, treaty bodies are often careful to maintain a respectful posture toward states parties, using diplomatic and increasingly technical language. Problem-solving language is common, suggesting an effort to cultivate a cooperative relationship while inculcating international procedural and substantive norms. Second, the quality and responsiveness of state reports represents evidence that (some) states are becoming socialized into international norms of accountability.

Learning and Capacity Building

Learning Best Practices

The report-and-review process is a dialogue—not an exam and certainly not a trial.Footnote 210 It is an opportunity for states to learn about best implementation practices or more efficient and effective methods to improve treaty outcomes. When review and dialogue accompany self-reporting, opportunities arise for state and international elites to “learn more about one another's position and perspectives, desires and constraints.”Footnote 211 Learning exactly how to implement one's treaty obligations is thus a highly plausible explanation for the correlation between cumulative reporting activity and rights improvements.

Implementing accepted norms—discussed above in the context of socialization—requires knowledge. Even if we all affirm that torture is “bad,” people of goodwill might not know how to keep it from happening. Even if we all agree that child labor is deplorable and not in a child's immediate interest or the long-run interest of a society, it is not altogether clear how to reduce it when families need the extra income. Fair trials may be widely embraced in principle, but it is not immediately obvious how to better ensure them in practice (and often with limited resources). This sort of learning is often factual and experiential, drawing heavily on a logic of consequences (“what works”).

In this sense, self-reporting resembles a type of global experimentalist governance that frames issues in a rather open-ended way: how can women's rights be strengthened? What forms of police training have the best shot at reducing torture in detention centers? The constructive dialogue attempts to solve such problems in light of locally generated knowledge and experiences, thereby contributing to localized efforts to improve capacity and compliance.

Information has a major impact on political and policy behavior.Footnote 212 Learning from other states’ experiences or from international organizations plays a central role in domestic regulatory practiceFootnote 213 as well as the diffusion of social and economic policies globally.Footnote 214 Learning is voluntary, purposive, and involves seeking out information to help solve a problem based on an improved understanding of what policies lead to better outcomes.Footnote 215 Multilateral reporting regimes often engender transnational networks involved in common implementation and compliance problems.Footnote 216 In this sense, self-reporting is less a mea culpa and more a part of what Charles F. Sabel and others call “global experimental governance,” itself a response to conditions of ignorance and uncertainty.Footnote 217

Both governments and the treaty bodies themselves can be expected to learn from the report-and-review process.Footnote 218 As Abram Chayes and Antonia Handler Chayes argue, learning processes are central to eliciting treaty compliance and effectiveness.Footnote 219 As early as 1953, the United States proposed that the goal of periodic review should be to “allow countries to draw inspiration and guidance from the experiences of other countries when trying to solve their own problems.”Footnote 220 Indeed, treaty bodies explicitly intend to convey the experience they have acquired in their examination of other reports.Footnote 221 The treaty bodies draw on collective experiences and information from myriad sources to expand knowledge available to governments and publics.Footnote 222 States gain advice about modes of implementation not previously known or considered. Learning is a shorter-term mechanism than elite socialization, though similarly iterative. Iterative reporting builds on learning opportunities to improve policies and practices over time.Footnote 223

Records of the review process provide clear evidence that teaching and learning is a prime goal of the committee members. The constructive dialogues and concluding observations are replete with suggestions found to be effective elsewhere. For example, during Chile's first review before the Human Rights Committee, Christian Tomuschat (Federal Republic of Germany) noted that “[e]xperience from other countries showed that workers had to be organized at the national level if they were to be successful in defending their interests.”Footnote 224 In reviewing Chile's most recent report before the CEDAW Committee, Marion Bethel (the Bahamas) suggested the government might consider prosecuting human traffickers under anti-money-laundering laws, noting that the “Argentinian authorities had recently begun to move in that direction.”Footnote 225 Learning best practices is similarly a goal for a number of governments who view the self-reporting process as an opportunity to “help strengthen domestic implementation by identifying areas of good practice”Footnote 226 and to “shar[e] best practice examples.”Footnote 227

The committees’ highly visible General Comments further reinforce learning and sharing of best practices.Footnote 228 In fact, this is their intended purpose.Footnote 229 General Comments are used to “share best practices with states parties, identify barriers to the enjoyment of Covenant rights, and to provide information on how rights violations may be prevented.”Footnote 230 For example, the Human Rights Committee's General Comment on freedoms of opinion and expression drew from over one hundred concluding observations and individual communications to elaborate legislative models for treaty implementation.Footnote 231

This Article does not offer direct proof that participants have learned specific best practices from interacting with the treaty bodies. Learning—and especially self-regulated learning—is difficult to measure, even in well-controlled settings with calibrated instruments designed to do so.Footnote 232 Nothing approaching a rigorous study of bureaucratic learning has been accomplished in the human rights literature. Rather, our focus is on whether the right conditions for learning are present during the report-and-review process.

To investigate this question, we looked to the composition of government delegations sent to Geneva—and specifically delegates’ connections with relevant domestic lawmaking and implementing organs—as a feature likely to improve the chances of carrying lessons back home. Latin American delegations to the treaty bodies were examined for the ICCPR, CEDAW, CAT, and CRC over the past decade. Governments typically send over a dozen officials with diverse levels and types of expertise. A handful are permanent diplomats in Geneva who are unlikely to return home with useful lessons on implementation. However, governments frequently send individuals from ministries and agencies tasked with implementing specific treaty obligations. For the CAT and ICCPR, representatives typically include both high-level officials and civil servants working in human rights departments from a country's Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Foreign Relations, Ministry of Defense, and Ministry of the Interior. Delegations often include individuals from the judiciary, senators, police chiefs, and a country's NHRI. For CEDAW, many of the same types of officials show up in Geneva, but they are typically led by a high-level official from a National Institute/Council of Women (Argentina and Mexico), the Ministry for Women and Gender Equity, the National Service for Women and Gender Equity (Chile), or similar institutions. Likewise, CRC delegations include policymakers and civil servants from agencies that deal specifically with youth planning and rights of the child.