I. Introduction

The U.S.-China trade relationship is beset by a clash of capitalisms, a clash of power, and a clash of values. Severe strains in the relationship pose a serious challenge to the multilateral trading system and have broad repercussions for international law. This Article addresses the three central dimensions of this relationship: (1) the economic dimension; (2) the geopolitical/national security dimension; and (3) the normative/social policy dimension. It assesses how these dimensions of the U.S.-China trade relationship can be managed, maintaining an important role for multilateralism and international institutions like the World Trade Organization (WTO) in relation to power-based bargaining, plurilateral and regional trade deals, and unilateral measures. The Article focuses on the U.S.-China trade relationship because of the implications of their great power rivalry for the multilateral trade legal order, but the principles that it sets forth apply broadly to the interface of heterogenous national systems in the context of geoeconomic competition.

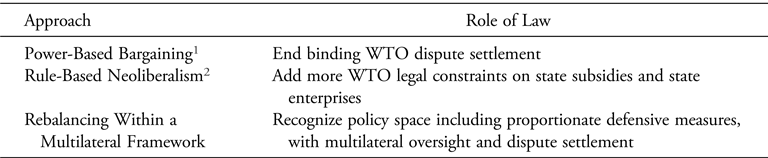

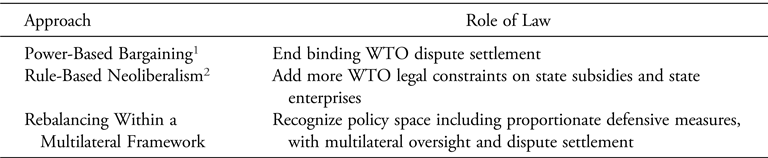

The Article advances a middle path between those rejecting the WTO in favor of a power-based system for trade governance, and those seeking to reinforce the WTO system with new rules that limit the state's role in the economy. The first approach represents “Power-Based Bargaining” and the second “Rule-Based Neoliberalism.” Both alternatives have powerful advocates within the United States and Europe. This Article, in contrast, proposes pragmatic reforms that would facilitate ongoing exchange while assuring latitude for each country to protect itself from the externalities of the other's policies. The result would be greater room for bilateral and plurilateral bargaining, but such bargaining would be conducted within the umbrella of the multilateral system. Call this third approach “Rebalancing Within a Multilateral Framework.” It involves the pragmatic rebalancing of national policy space in relation to international law constraints, including through accommodation of domestic safeguards on economic, national security, and social policy grounds. Table 1 summarizes the three approaches.

Table 1: Three Alternatives

A version of this third approach was previously articulated by the United States-China Trade Policy Working Group, whose Joint Statement I signed.Footnote 3 However, this Article significantly adjusts the Working Group's framework to provide a much greater role for multilateral rules and dispute settlement, and it makes concrete recommendations to implement this approach's basic principles in response to current economic, national security, and social policy challenges. Because there is no one form of economic governance that promotes development, much less one that universally applies across national contexts, multilateral rules must be sensitive to different economic, political, and social choices. At the same time, each country's policies should be subject to external scrutiny for their transnational implications, and other countries must be permitted to protect themselves from the external effects of that country's policies.

The approach proposed in this Article differs from two others that, respectively, advocate substantial economic decoupling from China with little role for law, on the one hand, and doubling down on constraining the state's role in the economy per a “liberal” economic model, on the other hand. The Trump administration exemplified the first approach, adopting unilateral tariff measures and moving toward significant if not—in its words—“complete” economic decoupling from China.Footnote 4 Its policies were widely criticized for their unilateralism, protectionism, and lack of effectiveness, but many critics sympathize with their targeting of China.Footnote 5

Petros Mavroidis and Andre Sapir's new book, China and the WTO, presents the contrasting “liberal” approach of doubling down on international law and adding further legal requirements on governments to adopt liberal policies, and “not preempt the market mechanism,” thereby further constraining governmental policy space.Footnote 6 In particular, they call for new legal requirements that go beyond non-discrimination norms to require governments and state-owned, state-invested, and state-linked enterprises to “behave in accordance with commercial considerations” and thus “create a good WTO” by bringing China “closer to ‘Western’ habits.”Footnote 7 Mavroidis and Sapir deploy “the West/non-West” dichotomy “as a shortcut to denote the relative degree of state intervention in the economy,”Footnote 8 using the term “West” eighty-two times in reference to a “liberal,” “market” economic model.Footnote 9 The adoption of their proposal could reflect what many call an “embedded neoliberal” economic model, one required and enforced by an international institution under international law.Footnote 10 In the end, this approach has some resemblances to a power-based model in that it requires unilateral change by China to become like “the West.” Were China to refuse to do so, the result would be power-based bargaining and the demise of multilateral trade governance through the WTO.Footnote 11

In contrast, this Article eschews requiring that China and other emerging economies must become like “one of us” in the “West.”Footnote 12 It rather provides a critical role for multilateral governance that does not require governments to abandon state intervention in the economy, such as through industrial policies and state ownership. Whatever one's views about the appropriate role of the state may be, governments should be free to make mistakes in advancing their economic development objectives. They should not be constrained by international law from pursuing particular interventionist development policies.Footnote 13 Under this approach, countries nonetheless are entitled to take measures to protect themselves from the externalities of other countries’ practices. This could result in some economic decoupling as compared to the WTO system in its first two decades, but such measures could also lead to new normative settlements conducted under the umbrella of the multilateral system. This Article recognizes that the lack of transparency of many of China's trade practices makes both defensive measures and ongoing negotiations essential. The Article maintains, however, that the WTO's fundamental norm should remain non-discrimination, coupled with transparency, not market fundamentalism.Footnote 14

The Article begins in Part II with an assessment of the geopolitical and domestic economic challenges of our time and then summarizes, in Part III, the Article's adjustment of the U.S.-China working group's guiding principles to retain a greater role for multilateral rules. The Article breaks down the issues along the economic, geopolitical, and social policy dimensions of the U.S.-China trade relationship. By the economic dimension, examined in Part IV, the Article refers to the U.S. critique of China's state capitalism, and in particular the use of state-owned enterprises and state subsidies, including in relation to technological development.Footnote 15 The geopolitical/national security dimension, examined in Part V, addresses U.S. concerns over China as a rising power bolstered by China's economic success in competing for innovation, coupled with worries regarding Chinese infiltration of infrastructure, gathering of data, and other forms of geopolitical leverage. The normative/social policy dimension, the subject of Part VI, concerns reactions to China's authoritarianism, human rights violations, and labor practices, which indirectly implicate U.S. workers, consumers, and the U.S. social bargain through purchases of Chinese products. Part VII addresses the role that multilateral dispute resolution can play in this new context. A brief conclusion follows.

In applying the framework across the three dimensions of the U.S.-China relationship—the economy, national security, and social policy—the Article develops specific proposals regarding each one. First, it assesses ways that the interpretation, reform, and application of WTO rules, including import relief rules, can provide greater leeway for the United States and other countries to respond to subsidies provided to state-owned enterprises and other state-connected businesses. Second, it considers how national security exceptions in trade agreements can be adapted to address cybersecurity, critical infrastructure, and related concerns. Third, it develops ways that existing WTO rules can be elaborated to permit countries to address social dumping. In each context, the Article considers the mechanisms being developed in bilateral and plurilateral agreements involving the United States, Europe, and China, respectively.

II. A New Situation Sense

Legal realists insist that rules should be adapted and applied in light of underlying social contexts.Footnote 16 For trade law, the underlying social and political contexts have radically changed internationally and domestically since the WTO's creation in 1995. Most dramatically, the United States is no longer the global hegemon, and the European Union also has relatively declined as an economic force. China, meanwhile, has become a global economic power as well as a regional military one. China's share of global GDP is now two-thirds that of the United States in nominal terms and over twenty percent more than the United States in terms of purchasing power.Footnote 17 Within a decade, China should become—once more—the world's largest economy.Footnote 18 China already is the world's largest trader, and two-thirds of countries trade more goods with China than the United States, compared to just one-fifth in 2001, the year China joined the WTO.Footnote 19 Particularly worrisome to the United States, China is a growing power in advanced technology, including information and communication technology. As a result, the United States and Europe, although still economically powerful, are less able to dominate rulemaking than in the past to reflect their domestic laws, economic models, and interest group demands.Footnote 20

It is not just the international context that changed; domestic contexts did as well. Inequality rose starkly in countries around the world, especially in the United States. The result has been levels of inequality not seen since the 1930s, contributing to a surge of populism and political tribalism, accompanied by greater wariness of economic globalization and the international institutions and laws that govern it.Footnote 21

These processes deepened as the COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc. China's economy grew 2.3 percent in 2020,Footnote 22 while that of the United States declined by 3.5 percentFootnote 23 and the EU's plummeted by 4.8 percent (and 5.1 percent for the Eurozone).Footnote 24 Within the United States, the gap between Wall Street and Main Street widened. The U.S. stock market soared to record highs in 2020, with oligopolistic digital companies profiting,Footnote 25 while unemployment rose to over fourteen percent and scores of small and medium-sized businesses went bankrupt or were spared only through massive government subsidies.Footnote 26

These domestic and international dimensions interrelate. Trade theory has long recognized that trade creates losers as well as winners. Globalization supported by international economic law created bargaining leverage for capital over labor, while constraining states’ ability to tax mobile capital.Footnote 27 Trade, when linked with technological change and the free flow of capital, placed downward pressure on the wages and job security of low-skilled workers, particularly in the United States.Footnote 28 Empirical studies show that massive imports from China, in particular, decimated many communities in the United States and Europe.Footnote 29 This invigorated populist politicians playing off nativist, racialized fears, and a loss of status.Footnote 30

These two dimensions together constitute a double-edged shift in inequality.Footnote 31 From a global perspective, trade simultaneously helped reduce inequality between countries because of higher economic growth rates in Asia and the rise of a middle class in China and India, while it helped increase inequality within countries.Footnote 32 Since the WTO provides a core part of globalization's legal architecture, it is not surprising that U.S. citizens left behind helped elect a reality TV star and economic nationalist as president who bashed it. As China rose as an economic and military power, U.S. national security officials also became warier of the trading system's implications, which reframed U.S. assessments of trade with China in security and geopolitical terms.Footnote 33

These shifts are critical to explaining how the United States became the great disruptor—“the wrecking ball”Footnote 34—of the world trading system and demanded its structural overhaul. The United States neutered the WTO's dispute settlement system. By terminating the appeals system, it ended the binding force of WTO rulings (subject to a subset of WTO members’ creating a separate arbitral procedure, discussed in Part VII).Footnote 35 Although the Biden administration is more internationalist in orientation than its predecessor, it is wary of WTO legal constraints on its “make-in-America” domestic policy agenda.Footnote 36 U.S. administrations change, but across the political spectrum there has been a sea change in U.S. citizen views toward China.Footnote 37

These U.S. shifts in perspective result from a number of factors, including the international and domestic structural changes described above, the onslaught of Trump and Biden administration rhetoric regarding the China threat, the authoritarian turn of the regime of President Xi Jinping, and the regime's enhancement of the role of the state and the Communist Party in China's economy and corporate governance.Footnote 38 In addition, under President Xi, the regime became much more aggressive in its behavior, ranging from its repression in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, its expansionism in the South China Sea and along its border with India, to its “wolf diplomacy” during the coronavirus pandemic.Footnote 39

Given this new context, the question arises whether the United States and China can develop a framework to address the different dimensions of their trade relations in order for the multilateral system to remain relevant in supporting economic development, resilience, stability, and peace.

III. A Guiding Framework for the Three dimensions of the Relationship

A. The Guiding Framewortk

Before examining particular rules, it is critical to develop a guiding framework for managing the three dimensions of the interface of U.S.-China trade relations.Footnote 40 The dominant paradigm in U.S. discourse is that either China must undertake significant reforms that reduce state intervention so that its economic system becomes more like that of the United States, or the two economies must significantly “decouple.”Footnote 41 As part of decoupling, high tariffs, product bans, and export and investment controls would become the norm. The result could be deepening conflict and the unraveling of cooperation in other domains, such as over the amelioration of climate change, the combatting of global pandemics, the stemming of financial crises, and the fostering of peace.

There is, however, a middle ground that would facilitate ongoing trade while assuring policy space for each country to protect itself from the externalities of each other's actions, including to protect its national security and uphold its social commitments. This approach has several salutary features. It recognizes that different countries favor different approaches to organizing their economies in light of their contexts, values, and preferences. It is modest, arguing against the notion that “one size fits all” for development, much less for capitalism generally.Footnote 42 It contends that countries can learn from a diversity of approaches, and that such diversity enhances the global economy's resilience when financial crises strike. It eschews deep harmonization, and it calls for greater acceptance of domestic policy discretion. This approach thus favors a rebalancing of economic relations that increases domestic policy space as compared to current international trade rules as they have been interpreted within the WTO system. It would accommodate some decoupling of the two economies as they negotiate over particular trade conflicts, but it would preserve the overall multilateral system. Moreover, it could do so, for the most part, though applying the existing WTO legal framework in a more deferential manner.

The United States-China Trade Policy Working Group has developed a set of governing principles that accommodate the United States’ and China's different economic systems and policy concerns in this vein.Footnote 43 The Working Group proposes to assess the governance of national policies in terms of four categories, or “buckets”: (1) those policies proscribed for their predatory nature; (2) those subject to bilateral negotiations; (3) those providing for unilateral measures where bilateral negotiations fail, provided they are proportionate; and (4) those regulated through multilateral rules because of potential spillover effects from bilateral agreements on third parties.Footnote 44 In the words of its Joint Statement, a framework should respect “each country's ability to design and implement its own domestic policies, to promote productive negotiations about how to share the benefits and minimize the harms that attend bilateral trade, and to facilitate fair competition in the multilateral sphere of international trade.”Footnote 45

This Article adjusts the framework by expanding the first and fourth categories to incorporate the fundamental WTO principles of non-discrimination and transparency, by expanding the second category to include plurilateral agreements, and by maintaining a key role for WTO dispute settlement. Moreover, it shows how the framework's guiding principles can be applied to different situational contexts implicated in the U.S.-China trade relationship besides economic relations and claims of economic fairness. Yet, like the Working Group, it stresses that multilateral rules need to accommodate bilateral agreements and unilateral action, while ensuring that unilateral responses are proportionate and that bilateral deals do not prejudice third parties.

The Working Group prescribes national policies that are predatory in orientation under Category 1. The definition of a “beggar-thy-neighbor policy” is one that seeks “to increase domestic economic welfare at the expense of other countries’ welfare.”Footnote 46 China's export bans and taxes on critical materials, such as rare metals required in high-tech industries, exemplify such policies, as do U.S. export bans on inputs used in the production of silicon chips for Huawei and other Chinese companies.Footnote 47 However, as Part V shows, the analysis becomes complicated when a national security frame is used to assess “beggar-thy-neighbor” measures as opposed to an economic one, which illustrates the need to apply a framework of principles across all three dimensions of the relationship.

Under Category 2, where countries disagree on the legitimacy of different policy approaches, they still might negotiate a bilateral settlement. Given the stalemate in WTO negotiations and the tensions between the United States and China regarding their respective policies—such as over China's subsidies and technology policies, and the countries’ respective tariff rates—ongoing negotiation between them is critical. These negotiations, in theory, can be multilateral, but it will be much easier to reach agreement through bilateral or plurilateral negotiations. This Article therefore expands the Working Group's Category 2 to encompass plurilateral agreements, including ones in which countries can coordinate their responses to China's (and any other countries’) practices.

Under Category 3, where a bilateral agreement is not reached, a country may adjust and respond unilaterally to protect itself, but such action must be proportionate to the harm caused. The principle of proportionality is central to international law, from the law of war to international trade and investment law.Footnote 48 The critical issues are how the principle is applied and who applies it. The determination of what is proportionate could be reviewed under multilateral rules, a bilateral or plurilateral agreement, or under a less formal arrangement.Footnote 49 Examples of potential unilateral adjustments include tariffs or product bans applied on national security or labor rights grounds, and border tax adjustments applied to carbon-intensive imports as part of a non-discriminatory climate change policy.Footnote 50 WTO rules already implement the principle of proportionality regarding remedies—a WTO member may be authorized to withdraw concessions in an “equivalent” amount to any “nullification or impairment” of benefits under a WTO agreement.Footnote 51

Under Category 4, policies agreed to bilaterally (falling within Category 2) and applied unilaterally (under Category 3) must be disciplined, especially where they adversely affect third parties. Multilateral rules can help to address these spillover effects. Under the most-favored-nation clause in Article I of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), any bilateral agreement falling within Category 2 may not discriminate against other WTO Members, such as by requiring the discriminatory purchase of one country's products over those of another.Footnote 52

Critically, this Article adjusts and expands Categories 1 and 4 to cover not only multilateral rules that prescribe “beggar-thy-neighbor” policies and protect third-party interests, but also those that require non-discrimination and transparency, require proportionate unilateral responses, and otherwise facilitate international coordination and cooperation. This Article's adaptation of the framework's guiding principles thus preserves a much greater role for existing multilateral rules, and, in particular, the fundamental principles of non-discrimination and transparency.Footnote 53 Yet, in doing so, this Article nonetheless aims to implement the Joint Statement's spirit and core principle that multilateral rules must provide policy space for countries to govern themselves, including by protecting their constituents through unilateral measures, and by accommodating bilateral and plurilateral bargains, subject to the proportionality principle and protection of third parties.

B. Implementing the Framework Across Three Dimensions

Implementing these guiding principles through multilateral trade rules has two main components. On the one hand, countries should have the right “to design a wide variety of industrial policies, technological systems, and social standards.”Footnote 54 On the other, they should have the right to use tariffs and non-tariff measures “to protect their industrial, technological, and social policy choices” in a manner that does not impose unnecessary or disproportionate impacts on foreign countries.Footnote 55 Both prongs are about balancing policy space with the need for multilateral rules and oversight.

Under this approach, China and other emerging economies would have the choice to organize their economies in different ways. However, China would recognize that those choices can affect constituencies in other countries. Countries would have the right to take proportionate measures to protect themselves and their domestic social bargains, in particular through discrete safeguard measures. Multilateral rules, in parallel, would prohibit discriminatory trade policies, and they would be backed by binding dispute settlement. This approach would not require a major renegotiation of multilateral rules, but it would demand adjustments, including in the interpretation of existing rules in dispute settlement, as well as through bilateral, plurilateral, and multilateral negotiations, as Parts IV–VI address.

This Article creates a typology of the interface of U.S.-China trade relations across the three dimensions of the economy, national security, and social policy. It does so primarily for expository purposes to demonstrate how the framework applies in each dimension. The Working Group framework, in particular, elided its application to national security concerns and did not explicitly address the social policy dimension. In practice, however, it is also important for purposes of legal interpretation and application.

Analytically, it often is difficult to discern whether a trade measure involves only one dimension compared to others because, in practice, a single trade measure may not only intersect with multiple dimensions of the interface, but a party may defend its measure under multiple or alternative frames. For example, measures to ban Chinese technology products can be viewed as a national security policy (to protect from Chinese espionage), an economic policy (to protect the U.S. lead in advanced technology), and a social policy (to protect Americans from Chinese surveillance and manipulation). Similarly, climate change mitigation measures can be viewed as a social/environmental policy, an industrial policy (as under a New Green Deal), and a national security policy. China could advance analogous arguments.

A particular challenge is that the Working Group's concept of “beggar-thy-neighbor” policies is an economic one that applies less well within a security frame since the goal of a security measure is to constrain an opponent. Countries, for example, aim to obstruct their rival's ability to obtain and develop advanced technology that can be used for weapons systems or otherwise can be weaponized economically.Footnote 56 The Working Group's concept of “beggar-thy-neighbor” policies also does not apply well to the social policy dimension because human and labor rights violations target a country's own nationals, not those of a third country.

Moreover, legal exceptions to tariff bindings and product bans are worded differently in WTO agreements regarding economic, social policy, and national security defenses, creating incentives for a respondent to choose a defense that grants it relatively more discretion. It is thus important to draw boundaries to determine the applicable rules and exceptions. This boundary work can be developed through negotiation, judicial interpretation, and practice, as Parts V and VI address.

WTO negotiations are stalemated, and existing WTO rules are outdated as regards new technologies that shape the digital economy and help drive U.S.-China trade conflicts. As a result, bilateral negotiations and unilateral action will be of growing salience. This framework thus applies both to the WTO and beyond it. For the WTO multilateral system to remain resilient, WTO decisionmakers must acknowledge the shift toward a pluralist approach to trade governance, especially in light of technological changes in geopolitically charged times. Most importantly, the principles set forth in this framework could help temper the trade war between the United States and China and its spillover effects on the rest of the world, leading both to greater accommodation and cooperative relations.

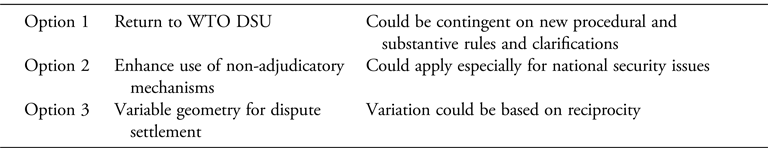

In practice, countries inevitably will disagree about the framework's application, even if they agree on the general principles. The United States, for example, may argue that China's industrial policies are predatory, and China may contend that U.S. technology policy aims to stem China's rise and trap its economy in lower value production. A critical question thus arises regarding the role of a third party in assessing the framework's application in light of applicable rules governing these three dimensions, especially given current blockages in the WTO dispute settlement system. The remainder of this Article first assesses current WTO rules under the framework, as developed in this Article, explicating how the rules might be applied and adapted (whether through modification or interpretation) to address each of the three dimensions of the interface. It then turns to the critical question of dispute resolution in Part VII. Table 2 summarizes the issues.

Table 2: Governing the Interface of U.S.-China Trade Relations

IV. Governing the Economic Dimension

The economies of the United States and China present very different capitalist models.Footnote 57 The state and Communist Party play central coordinating roles within China, although the private sector remains the most vibrant part of its economic success.Footnote 58 The United States, in contrast, proclaims its model to be “free-market capitalism,” although the U.S. economy is often dominated by huge, oligopolistic companies and “big money” plays an outsized role in U.S. politics, which, in turn, affects U.S. economic regulation and the state's role.Footnote 59

The key question for trade law is whether the WTO order provides—or can provide—a common set of principles, rules, and institutions to govern the interface between these heterogenous economic systems.Footnote 60 Many commentators in the United States contend that China's model of state capitalism violates the “spirit” of the WTO's legal order.Footnote 61 Others maintain that a key role for the GATT was always providing an “interface” between different economic systems, including between the United States, Europe, and (later) Japan.Footnote 62 It thereby can support trade liberalization and its benefits, while permitting countries to protect their constituents from what they view as “unfair” foreign trade-related policies.

China's economic model and the U.S. response to China's rise pose severe challenges for the multilateral system. Under a “power-based bargaining” model, the United States must respond to China's threat to U.S. economic welfare by enacting high tariffs and export restrictions in order to bring China to the bargaining table and thereby constrain the Chinese state. The Trump administration's trade war exemplified this approach. Under a “rule-based neoliberal” model, new rules are needed to constrain China's use of state-owned enterprises and state subsidies and thus “reduce or remove state involvement in the Chinese internal market” such that all decisions are “made in response to market signals.”Footnote 63 If China does not conform, it is maintained, then the WTO will become irrelevant and “power-based bargaining” be inevitable.Footnote 64

In contrast, this Article proposes a pragmatic “rebalancing” of the trade relationship under a multilateral framework, which will facilitate economic cooperation and trade while permitting greater policy space for calibrated responses to economic externalities. It contends that the United States is right to be concerned about the impact of China's economic rise on U.S. domestic policy. The enmeshment of the U.S. and Chinese economies through global value chains supported by trade law benefited U.S. capital, U.S. technology companies, some U.S. manufacturers (because of low-cost Chinese inputs), and U.S. consumers. However, most Americans’ wages stagnated, their jobs became more precarious, and many communities were devastated.Footnote 65 Nonetheless, multilateral rules can accommodate legitimate U.S. responses to the impact of China's policies within it, particularly as regards U.S. workers.Footnote 66

A. Subsidies

President Xi's policies of strengthening China's state-owned enterprises and bolstering the party-state's commanding role in the economy exacerbated concerns that China's economic model violates the “spirit” of “WTO norms.” In response, the United States, European Union, and Japan joined forces to press for new multilateral rules that will constrain state intervention in the economy and the operation of state-owned enterprises, per a neoliberal rule-based model. In 2018, they launched a “trilateral initiative” to modify WTO rules under the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement).Footnote 67 In a statement on January 14, 2020, they proposed to ban a broad range of subsidies under the WTO and add other constraints on state policy, in addition to existing WTO obligations.Footnote 68 Their proposal contains four main components.

First, they seek to expand the list of prohibited subsidies to include the following: “unlimited guarantees; subsidies to an insolvent or ailing enterprise in the absence of a credible restructuring plan; subsidies to enterprises unable to obtain long-term financing or investment from independent commercial sources operating in sectors or industries in overcapacity; [and] certain direct forgiveness of debt,” while noting that they “continue working on identifying . . . additional categories.”Footnote 69 Second, they shift the burden of proof for a series of other subsidies onto the subsidizing member to show that “there are no serious negative trade or capacity effects,” which could approximate a ban given the difficulty of proving a negative.Footnote 70 Third, they expand the definition of “serious prejudice” to “include situations where the subsidy in question distorts capacity.”Footnote 71 Fourth, they create rules for using benchmark prices outside of the market of the subsidizing member where it is a “non-market economy.”Footnote 72

Although U.S. concerns over China's economic rise are understandable, there are multiple problems with further constraining industrial policy options under multilateral rules.Footnote 73 To start, governments provide subsidies for good policy reasons to support their economies from market failures. The reasons are multiple, and they include the role of subsidies in increasing returns to scale, learning by doing, enhancing other positive externalities and countering negative ones (such as environmental harm from carbon-intensive industries). Demand for governmental support becomes particularly acute when private markets collapse in times of financial stress. The U.S. government's huge bailouts and support programs during the COVID pandemic—the largest government intervention in the worldFootnote 74—is one example, and the U.S. bailout of the automobile industry during the 2007–2008 financial crisis is another.Footnote 75 Economic theory does not support placing such straitjackets on government industrial policy, especially for economic development. And the United States would not want WTO dispute settlement panels to constrain its policy responses.

More generally, the idea that a WTO dispute settlement body, which the United States already criticizes for being too activist, can differentiate between a “credible” and “non-credible” restructuring plan seems fanciful. As law-and-economics scholar Alan Sykes writes, “subsidies may create negative international externalities and distort global resource allocation,” “but they may also represent sensible policy responses to a range of market failures” and play other useful roles.Footnote 76 Moreover, as Sykes stresses, subsidies represent government funds from citizens of one country that reduce prices for citizens in another, thus benefitting the latter country and its citizens.Footnote 77 Although constraining subsidies can help preserve market access bargains for exporters, countries might be wary of entering trade agreements in the first place if they are so constrained.Footnote 78

From the perspective of the different categories discussed in Part III, domestic subsidies generally are not “beggar-thy-neighbor” policies harming global welfare, and thus generally do not fall within Category 1.Footnote 79 Rather, by reducing prices in the importing country, the subsidizing country shifts the “terms of trade” in that other country's favor, actually benefitting that country from a welfare perspective.Footnote 80 One country's subsidies can adversely affect foreign producer groups, but they generally increase the importing country's national welfare because of the reduced prices subsidized by foreign governments and taxpayers.Footnote 81 Where the impact on producer groups raises political concerns, countries can bargain with each other to remove the subsidy's adverse effects (as captured in Category 2).Footnote 82 Otherwise, countries retain the discretion to take proportionate action to remove the subsidy's impact (under Category 3).

WTO rules already exist to implement these principles (Category 4). On the one hand, they permit countries to take unilateral action and raise countervailing duties in a proportionate manner against subsidized imports where they result in material injury to a domestic industry.Footnote 83 These duties, or the threat of imposing them, can trigger negotiations that result in the subsidies’ revision or removal. In practice, the United States, European Union, and Japan could coordinate the imposition of countervailing duties on Chinese products where the relevant criteria are met, thereby enhancing their leverage on China to remove the subsidies.

In addition, existing WTO rules create limits on industrial policy, which many economists maintain already go too far.Footnote 84 In particular, WTO rules “prohibit” export subsidies and subsides conditioned on the use of domestic products,Footnote 85 and they make actionable any subsidies to “specific” industries that cause “adverse effects” on another WTO member, including for that member's exports to third-country markets.Footnote 86 Brazil, for example, successfully challenged the United States regarding U.S. agricultural subsidies in ways that caused “serious prejudice” for Brazilian producers on global markets.Footnote 87 WTO rules also provide a mechanism that enables countries to preserve reciprocal market access bargains through “non-violation nullification and impairment” complaints on the grounds that the subsidy nullifies the benefits of a market access commitment.Footnote 88 In theory, WTO legal constraints could be expanded, but achieving consensus on such an expansion is unlikely, and, even if it were reached, it could constrain government policy space in unjustified ways.Footnote 89

The primary problem with the application of existing WTO rules is not that they fail to sufficiently constrain China's and other emerging economies’ use of industrial policy for development purposes, which would be inappropriate. Rather, the problem is that they can place too many constraints on countries seeking to protect their key industries and broader social bargains from the impact of foreign trade, including foreign subsidized products. Existing rules could be applied, reinterpreted, or revised to permit greater protection against the impacts of third-country subsidies in three ways: (1) through further clarifying the definition of the term “public body” for purposes of subsidies and countervailing duty law, implicating the transparency of subsidies channeled through state-owned and state-connected enterprises; (2) through easing the application of safeguard rules to permit for economic adjustment, so that safeguards can be applied where subsidies create overcapacity, and thus counter the risks of trade diversion from third countries not covered by countervailing duties; and (3) through creating and applying existing rules that incentivize making the subsidies more transparent, which represents good domestic as well as external policy.

First, the WTO Appellate Body interpreted existing WTO rules under the SCM Agreement that could make it more difficult to establish a subsidy where the subsidy is provided through a state-owned enterprise, which practices raise transparency issues, as further developed below. Under the agreement, a “subsidy” is defined in terms of “a financial contribution by a government or any public body within the territory of a Member.”Footnote 90 On the question of whether a state-owned enterprise is a “public body,” the Appellate Body found that it may be deemed one only if it is vested with “governmental authority” and performs a “governmental function,” citing public international law texts on state responsibility in support.Footnote 91 Many commentators severely criticized the Appellate Body decision, in large part because Chinese state-owned enterprises without explicit governmental authority are often required to provide loans and promote the development of particular economic sectors, and the government often is not transparent, making it difficult to prove particular state-owned enterprises are acting with government authority.Footnote 92

However, in 2019, the WTO Appellate Body clarified its approach in a way that reduced the burden on investigating authorities. In particular, the Appellate Body found in favor of the United States that an investigating authority does not need to establish a connection between a state-owned enterprise and the government in terms of “conduct” related to a specific transaction, but only generally as an “entity.”Footnote 93 It also noted that even private entities can operate as public bodies where the entity has close links with the government involving particular conduct.Footnote 94 Many commentators thus contend that existing WTO provisions may be sufficient to challenge such Chinese policies,Footnote 95 including Chinese scholars.Footnote 96 In particular, some note how investigating authorities can use provisions of China's Protocol of Accession, together with the Working Party Report to its accession, to support import relief measures against China's subsidies.Footnote 97

Moreover, norm clarification and development are occurring not only through jurisprudence, but in parallel through the negotiation of bilateral and plurilateral agreements. The United States successfully pressed to define the term “public body” in terms of ownership in the TransPacific Partnership (TPP) (under the Obama administration) and the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) (under the Trump administration).Footnote 98 China has applied to join the CPTPP, suggesting that this issue could be successfully negotiated, especially given the evolution of Appellate Body jurisprudence.Footnote 99 In its Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with the European Union, concluded on December 30, 2020, China also agreed to a more expansive definition of a “covered entity” that is required to “act in accordance with commercial considerations.” The substantive commitments cover any “enterprise in which a Party has the power to legally direct the actions or otherwise exercise an equivalent level of control,” as well as any “public or private” enterprises that are “designated by a Party, formally or in effect, as the only suppliers or purchasers of a particular good or service in a relevant market.”Footnote 100

Second, countervailing duty rules arguably fail to provide protection where China's practices lead to trade diversion from third countries. As Chad Bown and Jennifer Hillman explain, China's subsidies can lead to severe overcapacity in production affecting industries around the world. Applying tariffs to imports from China can divert Chinese products to third countries, placing downward pressure on prices that, in turn, generates exports from these countries to the United States. These exports can simply displace those earlier coming from China—which were subject to U.S. import relief measures—so that affected U.S. companies and their workers continue to be harmed. Bown and Hillman show how this dynamic has occurred in the steel, aluminum, and solar panel sectors.Footnote 101

Broader safeguards are thus a better option to provide industry time to adjust, as trade negotiators address the overcapacity problem.Footnote 102 A significant challenge, however, is that the WTO Agreement on Safeguards, as interpreted in Appellate Body jurisprudence, severely limits when safeguards can be applied. Under the Safeguards Agreement, a WTO member must show that “increased imports” “have caused” or “are threatening to cause” “serious injury” to a “domestic industry.”Footnote 103 As Sykes notes, it is “incoherent” to require a showing of causation of increased imports since the imports are a function of supply and demand as a whole.Footnote 104 In addition, for a safeguard to be legal, the Appellate Body has required a showing of “unforeseen developments” since “the obligations incurred,” as provided under Article XIX of the GATT, but absent from the detailed 1994 WTO Agreement on Safeguards.Footnote 105 In practice, the WTO Appellate Body has never found a safeguard to be compliant under its interpretation of WTO requirements.Footnote 106

A better approach is to interpret and apply the Safeguards Agreement in light of its object and purpose to provide certain flexibility to governments when a domestic industry is seriously harmed while imports rise so that industry can adjust and governments can respond to broader social and political challenges.Footnote 107 A more deferential approach would provide greater policy space for governments where they can show increased imports and serious injury, or a threat thereof, to a domestic industry. The safeguard measures, when proportionate to address adjustment, would relieve pressure on officials to take more drastic measures, such as to forego trade liberalization, including on “national security” grounds.Footnote 108 The resulting measures will raise some trade tensions, but they also can trigger negotiations to adjust to the situation, such as to reduce underlying overcapacity problems (Category 2). Revised rules or a revised interpretation of existing rules can thus help maintain relatively more harmonious and mutually beneficial trade relations in the current context. Negotiations over the relationship of binding WTO dispute settlement between the United States and other WTO members provides an opportunity to clarify these rules or develop more general guidelines for future panels to interpret existing safeguards rules in light of their underlying purpose. Such an amendment or guidance would not single out any particular WTO member, while providing all members with greater policy space to respond to trade shocks.

From a traditional law-and-economics perspective, the appropriate response to economic dislocations caused by trade lies in domestic redistributive and adjustment policies.Footnote 109 However, in practice, buffers to trade may be needed, and safeguards provide a targeted means of providing them. Unlike WTO countervailing duty and anti-dumping law, safeguards also permit for the rebalancing of trade concessions.

Third, the United States finds that China's regulatory practices are non-transparent so that it is extremely costly, if not impossible, to build a factual case for WTO complaints. The transparency issue has two main aspects when applied to China. The first aspect concerns the role of state-owned, state-invested, and state-connected enterprises in engaging in non-market-oriented behavior, such that China's industrial policy is much less transparent than when subsidies are provided directly by the government as part of a published regulatory policy.Footnote 110 The second aspect concerns the role of formal notifications of subsidies to the WTO. In both instances, there are strong arguments for requiring greater transparency as a public good that is important not only for trade relations, but also for domestic governance to limit rent-seeking, reduce information asymmetries, and enable firms, citizens, and trading partners to know what governments are doing.Footnote 111

The first aspect, and a significant challenge for the U.S.-China trade relationship, is the lack of transparency of China's industrial policy when conducted through state-owned and state-connected enterprises. The problem, however, is generally not with existing WTO rules pertaining to China. China agreed in its Accession Protocol that its state-owned enterprises will make purchases and sales on a commercial basis. In particular, paragraph 46 of the Report of the Working Party on the Accession of China is a binding “commitment” under its Accession Protocol.Footnote 112 This paragraph provides:

The representative of China further confirmed that China would ensure that all state-owned and state-invested enterprises would make purchases and sales based solely on commercial considerations, e.g., price, quality, marketability and availability, and that the enterprises of other WTO Members would have an adequate opportunity to compete for sales to and purchases from these enterprises on non-discriminatory terms and conditions.

Thus, under China's Accession Protocol, it agreed that its state-owned and state-invested enterprises would operate as commercial enterprises, such that any industrial policy measures aimed at benefitting upstream or downstream firms would have to be provided by the government itself.

Some commentators contend that such a provision on state-invested enterprises should be placed in the WTO covered agreements and applied to all WTO members.Footnote 113 Such a commitment would supplement existing WTO legal constraints on any “specific” subsidy—one that “limits access to a subsidy to certain enterprises.”Footnote 114 However, since the WTO does not impose competition law obligations regarding private enterprises, it seems unfair—and indeed discriminatory—to single out the economic behavior of state-owned enterprises, especially given the dominance of oligopolistic U.S. companies in information technology sectors. Moreover, there are serious reasons to pause before extending more WTO constraints regarding the state's role in the economy for the policy reasons earlier noted.Footnote 115

Nonetheless, even if one contends that such constraints should be added to a WTO covered agreement, the fact remains that China already has made this commitment in its Accession Protocol and that has been insufficient to assuage economic tensions with the United States. It is for this reason that this Article focuses on policy space for defensive measures combined with bilateral and plurilateral negotiations over conflicts. WTO rules must permit the United States and other countries to protect themselves from non-transparent subsidies provided through state-owned and state-connected enterprises that advantage Chinese producers. If the United States, European Union, and others coordinate their investigations and responses to non-transparent Chinese practices, they will increase their leverage on China to enhance the transparency of the practices of state-connected enterprises. Indeed, China's Accession Protocol already provides discretion for investigating authorities to use external benchmarks when calculating subsidies if there are “special difficulties,” such as distortions caused by government interventions in China's internal market, including through state-connected enterprises.Footnote 116 To the extent that China wishes to pursue industrial policies in a manner not subject to countervailing duties, coordinated measures could press it to do so in a more transparent way.

The second transparency challenge is that of formal notifications of subsidies. The SCM Agreement requires that members report their subsidies each year to the WTO Committee on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures,Footnote 117 but the record of industrial subsidies notification is poor, with over half of WTO members not notifying the WTO committee.Footnote 118 To enhance transparency, the United States and others have proposed sanctions against countries that fail to notify their subsidies, such as a suspension of particular WTO benefits.Footnote 119 One option is to modify WTO rules so that specific categories of subsides are affirmatively permitted under WTO rules, as originally provided under Article 8 of the SCM Agreement but which expired under that agreement's terms without being renewed. A country's failure to meet its reporting obligations could trigger a suspension of the ability to benefit from the exempted category.Footnote 120 Such a sanction could incentivize reporting in ways that the current SCM Agreement does not. Although a renewed Article 8 might not be feasible at this time, bilateral and plurilateral negotiations with China also can address transparency concerns. For example, the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment includes new transparency requirements regarding subsidies, coupled with consultation mechanisms.Footnote 121

There are multiple explanations for attacks on China's economic model. Some critiques reflect justifiable concerns about a lack of transparency, which unfairly affects foreign traders and can nullify market access commitments that China made. Others simply reflect a political shift in the United States where attacking China has become a political benefit, one which deflects from U.S. policy failures. And others reflect neoliberal prejudice against the role of government in economic policy.

Yet, if commentators believe that industrial policy is the wrong approach because government decision making is less efficient than the market, then they should let the United States and China compete, ideologically assured that the U.S. approach will triumph. Indeed, there is significant tension, if not contradiction, in the arguments of those advocating that new rules should be added to the WTO to constrain Chinese state-owned enterprises, while at the same time contending that China's economy would be more productive if it privatized them so that they operated freely on a market-oriented basis.Footnote 122 In contrast, if China's industrial policies indeed help spur development in new sectors, then the United States might learn and engage in its own targeted industrial policies, as reflected in calls for a “Green New Deal” advanced in the United States and to support technology development in Europe.Footnote 123 A better approach than adding further WTO constraints on state industrial policy is to ensure that WTO rules permit members to protect themselves from the externalities of state subsidies in a proportionate manner, which, in turn, can facilitate bilateral and plurilateral bargaining and settlements.

B. Forced Technology Transfers

Developing countries have long passed laws that tie investment approvals to technology transfer as part of their development strategy. Multinational companies, backed by their national governments, have opposed these requirements. They generally managed these situations by either refusing to transfer technology such that developing countries in need of capital investment backed down, or by transferring older technology for foreign operations. China poses greater challenges for two reasons. First, China exercises greater leverage to induce U.S. companies to transfer frontier technology because of the size of China's internal market. Second, China's rise as a technological power poses a greater risk that Chinese companies will become competitors, even when U.S. companies aim to deny access to their newest generation technologies.Footnote 124

The United States has legitimate concerns regarding China wielding leverage over access to its markets to obtain U.S. technology, although business surveys show that the problems are not as severe as presented in much “trade war” rhetoric.Footnote 125 China's Accession Protocol to the WTO prohibits “forced technology transfers” through government licensing, but most technology transfers occur in the context of joint venture negotiations required for a foreign company to operate in many economic sectors. Chinese government incentives can shape the bargaining leverage of the parties in these negotiations by setting conditions for tax benefits, other subsidies, and government procurement contracts.

Even where the government itself does not impose a technology transfer requirement (and China insists it does not do so),Footnote 126 the mere requirement of operating only through a joint venture arrangement creates structural conditions that facilitate technology transfers, which is why China and many developing countries require them. First, the Chinese government creates economic incentives for investment in China in technology sectors. Second, the government does not permit a foreign company to operate in China except through a joint venture. The quickest way for a Chinese company to enter such sectors, and thus benefit from government incentives, is to form a joint venture with a foreign company that already has technology and have it transferred to the joint venture. Foreign companies agree to such transfers in order to gain access to China's market and benefit from tax and other incentives. They, in effect, trade technology for market access and other benefits.

These private negotiations are not subject to WTO rules, unless the United States can prove that the Chinese government incentivized the transfers such that the transfers were “essentially dependent on Government action.”Footnote 127 The Obama administration worked to resolve these concerns through bilateral and plurilateral agreements, including through the negotiation of the TransPacific PartnershipFootnote 128 and a U.S.-China bilateral investment treaty, both of which the Trump administration abandoned.Footnote 129 The Trump administration, in contrast, aimed to address them by unilaterally raising tariffs and then using the threat of further tariffs as leverage to press for an agreement, which culminated in the agreement it signed with China in January 2020 that bans “forced” technology transfers.Footnote 130 The European Union subsequently also concluded a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with China in December 2020, which again prohibits forced technology transfers, while slightly expanding key areas where EU companies do not need to form joint ventures to enter the Chinese market.Footnote 131 The agreement with the European Union requires China not to “directly or indirectly require, force, pressure or otherwise interfere with the transfer or licensing of technology between natural persons and enterprises.”Footnote 132

The problem, however, is not with the legal texts, which already existed as part of China's Protocol of Accession and are reflected in Chinese law.Footnote 133 The challenge is to induce China to remove joint venture requirements in more sectors through negotiation, and thus eliminate this form of leverage. If an agreement is reached, new Chinese commitments could be incorporated under the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) for services sectors, or under new investment agreements covering both goods and services sectors.Footnote 134

Applying the framework set forth in Part III, there is a strong argument not to cover these types of technology transfer under multilateral rules given developing countries’ long-standing need for technology and companies’ ability to bargain with them. From this perspective, it is best for developing countries to retain policy space and handle technology transfers on a case-by-case, country-by-country basis. However, it is legitimate for the United States to address these issues bilaterally and plurilaterally with China (Category 2), particularly given their economic rivalry and the economic and national security stakes. Where negotiations fail, it likewise is legitimate for the United States to take unilateral measures to protect itself (as well as plurilateral measures coordinated with third parties), provided in each case that they are proportionate (Category 3). Already the United States has, in turn, heightened restrictions on Chinese investments in the United States under the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA), under which the interagency Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) operates.Footnote 135

The Obama administration might have prepared claims challenging China's alleged practices before the WTO under China's Accession Protocol and the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). It declined to do so, possibly because it lacked confidence in this approach, including because of the risk of Chinese retaliation against firms that provide supporting evidence. Instead, the Trump administration imposed unilateral sanctions against China following an investigation under Section 301 of the U.S. 1974 Trade Act regarding China's alleged theft, subsidized purchases, and “forced” transfers of U.S. technology.Footnote 136 The U.S. unilateral tariff measures violated WTO law, which China successfully challenged before the WTO.Footnote 137 However, China also retaliated immediately—before the WTO case was decided—which again violated WTO requirements.Footnote 138

In the end, China's sanctions were arguably parallel to what WTO authorized remedies would have been, subject to the time delay of bringing the case and the fact that WTO remedies are not retrospective.Footnote 139 Under WTO law, the remedy for a violation is that the prevailing member in a WTO claim may take measures “equivalent” to the amount that its benefits (under the WTO agreement) have been nullified or impaired, unless the respondent complies with the ruling.Footnote 140 In practice, China raised tariffs in a roughly equivalent amount to the U.S. tariffs. These U.S. and Chinese unilateral measures (Category 3) spurred the United States and China to negotiate bilaterally to address and manage this issue (Category 2). To the extent the bilateral arrangement has adverse effects on third parties, WTO rules create constraints. Indeed, when the United States settled its trade dispute with Japan during the GATT era, it negotiated a settlement that triggered a successful GATT challenge by the European Communities against Japan under the GATT most-favored-nations clause (Category 4).Footnote 141

However, if the United States had brought and prevailed in a WTO challenge against China's practices, China would have had no right to raise tariffs following a WTO-authorized withdrawal of concessions by the United States. Because the United States acted unilaterally, China had a right to withdraw an equivalent amount of trade concessions, with the result of high tariffs on both sides, suggesting that the United States could have been better served had it first brought a WTO case. Under this Article's framework, the parties may rebalance tariffs as they have done, but they also have incentives to comply with multilateral rules and use dispute settlement in light of the reciprocal costs of tit-for-tat retaliation.

V. Governing the Geopolitical/National Security Dimension

The most serious challenge to the U.S.-China relationship is geopolitical, especially at the technological frontier. China is a rival economic power globally and a rival military one in Asia. Because the national security concerns include China's subsidies to high-tech industry, this dimension overlaps with the first. The extent of the overlap is a function of one's conceptualization of national security, a contested concept whose meaning changes over time and situational contexts, but which generally signifies a demand of deference toward nation-state policy decisions.Footnote 142

Measures adopted to protect national security should be assessed differently than economic ones. National security measures often involve “beggar-thy-neighbor” and discriminatory policies and yet are viewed as legitimate measures of self-protection. Exceptions on national security grounds, when applicable, provide greater discretion to the implementing country, and countries are wary of third-party judicial review of such measures. For example, take national bans on trade in “fissionable materials” or other “implements of war.” They expressly fall within the GATT exception clause for national security (Article XXI). However, with China's economic and technological rise and the decline of U.S. hegemony, the scope of issues involving national security concerns has expanded, posing new challenges for a rules-based trading system.

Both China and the United States have raised new security concerns regarding trade, especially as regards reliance on the other for key technology and components.Footnote 143 Their respective trade and investment policy responses could lead to the decoupling of their economies in critical sectors. This Article focuses on internal U.S. debates regarding security issues involving trade because of the recent central role they have played in justifying U.S. restrictive trade and investment measures. Yet, it is important to recognize the reciprocal nature of these concerns, since reciprocity offers prospects for negotiated understandings and settlements.

It remains unclear whether the United States will take a narrower or broader approach to addressing national security concerns in trade policy. Under a broader, “geoeconomic” approach, the United States would adopt policies aimed at stemming China's economic rise,Footnote 144 which by definition includes China's development of “smart” manufacturing and products incorporating advanced technologies, sometimes referred to as Industry 4.0.Footnote 145 It thus might adopt more coercive policies aimed at curbing Chinese companies in key sectors, including through pressuring companies in third countries not to sell key inputs to them (as it has already done in some cases).Footnote 146 This broader approach risks responses that could lead to a more conflictual world order.

Under a narrower approach, the United States would focus on national security concerns involving particular technologies, although applied in the new situational context posed by technological developments and China's rise. Under this approach, the United States would wish to thwart China's obtaining advanced technology that it could use for military or other coercive purposes and to prevent China's gathering of intelligence and data that it could use to advance its international strategies and interfere in U.S. politics, including through blackmailing and manipulating U.S. officials and citizens.

In practice, there will be a spectrum of national security issues to which this Article's framework applies. First, from an expository perspective, irrespective of the conceptualization's scope, national security issues can be addressed under the general principles set forth in Part III, albeit with greater challenges in differentiating illegitimate economic predatory policies (Category 1) from legitimate national security ones. Existing multilateral trade rules already accommodate national security issues through exception clauses, although they would benefit from updating to address cybersecurity and critical infrastructure concerns, in particular (Category 4). These exceptions can and should accommodate unilateral adjustments (Category 3) that can spur bilateral negotiations and (potentially) lead to new bilateral and plurilateral settlements (Category 2).

The broader approach to national security in terms of geopolitical rivalry is expressly confrontational and more likely would lead to open conflict. The argument for adopting it is that the United States and China are already in a strategic rivalry, that China's economic power easily translates into military power, and so U.S.-China trade relations are by definition strategic in nature. From this perspective, then the United States should work to decouple its economy from China's, except where net benefits are balanced or accrue more to the United States from the relationship. The U.S. contestation of China's 2025 indigenous innovation initiative, in part, is because China threatens to take the lead in “smart manufacturing” at the cutting edge of technology.Footnote 147 In parallel, China's Belt & Road Initiative has a geopolitical dimension in forging economic ties (and dependence) through Chinese trade, investment, and finance.Footnote 148 In this vein, the 2017 U.S. national security plan declared that “economic security is national security.”Footnote 149

Conceptually, the position that all trade relations are also strategic ones may be true, but this truism does not inform policy choices over tradeoffs in different contexts. The main arguments cautioning against aggressive application of the broader approach are that China's rise is a reality that needs to be managed and that a broad, coercive approach to defending national security could backfire on the United States. Aggressive, uncalibrated attempts to block China's rise will most likely fail, exacerbate conflict, and impede collaboration in policy domains where it is critically needed. They not only would increase the risk of conflict (and thus reduce security),Footnote 150 but also could reduce U.S. competitiveness by cutting off U.S. industry from lower cost Chinese inputs, create conflict with other countries that trade with China and thus undercut alliances, and further incentivize Chinese companies, as well as companies in third countries, to develop technologies that replace U.S. ones and thus avoid U.S. sanctions.Footnote 151 Moreover, China and the United States must cooperate to address global challenges, such as climate change, pandemics, and financial crises, in which their fates are linked. Trade measures that are uncalibrated and disproportionate to the risks at stake will erode trust and undermine global cooperation in areas that are critical for U.S. national security.

This Article thus favors a less expansive, more calibrated approach to managing the interface of the U.S. and Chinese economies from the perspective of national security. It contends that the United States and China legitimately can ban each other's products, investments, and exports of sensitive technology, but that, under the framework set forth in Part III, they should do so in a manner proportionate to the security risk in question. Under this approach, each country can take targeted action that is proportionate to the national security concern, while maintaining cooperation and reducing the risk of downward spiraling, tit-for-tat escalations of conflict that undermine the security of both countries and their citizens.

This distinction between national security conceived more narrowly or broadly currently centers on the regulation of information and communication technologies. Rivalry in this area will be a precursor of issues affecting other high-tech domains, such as biotechnology and fintech, where the United States and China will promote rival products and systems.Footnote 152 Managing this competition in light of the conceptualization of security risks and proportionate responses to those risks will be central to the national security dimension of U.S.-China trade relations going forward.

In practice, states will differ in their assessments of the proportionality principle. The difficult issue is not the principle as such, which is critical for governing the interface of the U.S.-China trade relationship, but the amount of deference to be shown to domestic decisionmakers in applying it, and the role of international judicial and non-judicial mechanisms in assessing the legality of these domestic decisions. The next Section illustrates the application of the proportionality principle by considering U.S. treatment of Huawei and TikTok. The ensuing Section addresses dispute settlement mechanisms to govern national security defenses, and the analytic boundary between national security and economic measures.

1. Illustration Through Huawei and TikTok

A calibrated approach to national security requires differentiating the challenges posed by Huawei and TikTok. Huawei provides fifth generation (5G) network infrastructure for data transmissions central to the data-driven economy, including the internet-of-things. Sales of Huawei 5G infrastructure become security concerns not only because the infrastructure could facilitate espionage, but also because it could be “weaponized” by compromising system integrity and availability in response to a trade or actual military conflict, such as in the South China Sea, a conflict that could escalate into a cyberwar at immense costs to both sides.Footnote 153 For example, if a 5G network—which forms part of a country's critical infrastructure—were to be interrupted without an adequate backup system, social chaos could spread. The popular app TikTok, in contrast, primarily raises security concerns regarding the ability of China's government to obtain data on TikTok's users and potentially use it for blackmail and social influence over time.

As a general principle, trade measures should be proportionate to the security concern at issue. Their justification should depend on traditional factors in proportionality analysis—in this case, a balancing of the national security risk, the relation of the trade measure to the risk, the impact of the measure on third parties, and any alternative ways to address the risk that would have a less adverse impact on third parties while accomplishing the policy objective. National officials should review the risks and, if they determine that the risks are too high, bans on national security grounds are a legitimate response.

The U.S. banning of the use of Huawei's 5G technology for wireless networks in the United States exemplify trade-related national security concerns involving critical infrastructure.Footnote 154 Similar actions have been taken by Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, and spurred ongoing internal debates within the European Union regarding the use of Huawei equipment. The risk of compromised critical infrastructure, including of a sudden breakdown at a time of conflict, is simply too great. Similarly, under a proportionality analysis, it would be legitimate to ban exports of U.S. technology to Huawei where it is believed that Huawei products can be used to gather information on U.S. strategy through global communications networks and to coerce U.S. allies, not to mention their deployment for military purposes.

In contrast, the U.S. ban on the export of equipment and technology to companies in third countries that use them in the production of products that they sell to Huawei raises more challenging questions. For example, the United States has banned the selling of equipment needed for the production of silicon chips to companies in third countries that make and sell chips to Huawei.Footnote 155 Here the U.S. ban is extraterritorial in its reach, and it is no longer linked to U.S. critical infrastructure. It thus raises greater proportionality concerns. It escalates conflict with China, as the apparent aim is to undermine or destroy a major Chinese company, one employing almost two hundred thousand Chinese workers. It also raises conflicts with third countries affected by the ban, since they too have major companies employing tens of thousands of workers that will be harmed. In addition, developing countries depend on Huawei technology, which is much more affordable.

On the one hand, this approach could be viewed as a “beggar-thy-neighbor policy,” falling under Category 1, and thus be prohibited. On the other hand, the United States could contend that Huawei's development of critical infrastructure around the world carrying U.S. transmissions constitutes a national security risk. Analytically, because of the extraterritorial nature of the measures, the issue of their proportionality (under Category 3) becomes more salient. Such extraterritorial measures also will entail significant costs that, on balance, risk exacerbating conflicts in a manner contrary to U.S. interests, as noted above.Footnote 156

Turning to TikTok, a U.S. ban and coerced sale appears excessive.Footnote 157 A more proportionate measure is to ban use of TikTok by U.S. government officials, including military personnel, to the extent that such use could provide valuable data to China, including location data that might be used during a conflict. China, for example, adopted this approach by banning the use of Tesla vehicles by government officials and military personnel.Footnote 158 If the United States is concerned about the collection of data, it also can regulate how the data is collected through a comprehensive data privacy regime, as the European Union and many other countries do.Footnote 159 It likewise could require that any data collected be stored in the United States and not transferred to China, although the United States has opposed data localization requirements, and the effectiveness of such localization is questionable.Footnote 160 Overall, the national security risks in the TikTok case are much lower than regarding Huawei's construction of critical infrastructure. Such a ban, moreover, could spur tit-for-tat responses that disconnect U.S. and Chinese citizens and thus potentially exacerbate divisions that ultimately would reduce security. Thus, a general ban on the use of the popular app seems disproportionate from a policy perspective.

2. Boundary Work: Updating Existing National Security Exceptions and Mechanisms to Oversee their Application

A major challenge in this context will be drawing boundaries between national security and economic measures that are subject to different exceptions clauses in trade agreements. For example, economic safeguards can be applied under the WTO Agreement on Safeguards, but these measures must be temporary and, if they are not withdrawn after three years, affected WTO members may withdraw an equivalent amount of trade concessions. National security measures, in contrast, can be invoked so long as the national security concern remains, and the affected party arguably may have no right to withdraw concessions in an equivalent amount.

The trading system traditionally relied on members exercising constraint both in invoking the national security exception and in challenging such invocation. They acted under common norms regarding boundaries as to when it is appropriate (or not) to invoke national security. These common norms eroded over the last years.Footnote 161

One response is to update national security clauses to address new contexts while creating institutional processes to develop and oversee the application of soft law norms and understandings. This would encourage parties to use exceptions reciprocally to permit a proportionate rebalancing of concessions, which could give rise to a partial decoupling of U.S.-China trade relations in certain sectors. This rebalancing could relieve some pressure on Members resorting to the national security exception, as addressed further below. Where disputes nonetheless arise, the relative role and relationship of domestic and international political and judicial processes could be clarified as follows.