I. Introduction

In January 2021, as the Biden administration took office in the United States, many observers may have welcomed promises by top-level U.S. officials to treat “the climate crisis as the urgent national security threat it is.”Footnote 1 It is no doubt comforting to once again have a U.S. administration that purports to take climate change seriously, but what does it mean to count this as a “security” issue? Perhaps the label simply signifies the seriousness of the threat, acting as a call to reinvigorate environmental institutions, such as by rejoining the Paris Agreement or strengthening domestic regulatory authority over greenhouse gas.Footnote 2 But the label could have more sweeping implications. By invoking the concept of security in connection with climate change, the United States could be heading down a path toward invoking emergency powers, perhaps as a basis for imposing economic sanctions on polluting nations or private entities.Footnote 3 More darkly, this policy could signal a new trajectory for the use of force abroad, gesturing toward a future where “climate rogue states” are threatened with military force if they do not comply with environmental commitments.Footnote 4 Alternatively, we might hope that the label will draw attention to the differential impact of climate change on populations that already experience the greatest insecurity, thereby triggering calls for much more far-reaching reforms.Footnote 5 Each of these possibilities suggests a radically different trajectory for foreign policy and international law, yet each is contained within the notion of “security.”

The foregoing example concerns U.S. foreign policy, but similar questions are emerging worldwide and at all levels of the international system. Several states and the UN Security Council have acknowledged the security implications of the climate crisis.Footnote 6 And the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic is triggering calls to strengthen “global health security,” a concept with a long history but ambiguous implications.Footnote 7 States are describing cyber-threats,Footnote 8 organized crime,Footnote 9 money laundering,Footnote 10 bribery,Footnote 11 human trafficking,Footnote 12 supply-chain issues,Footnote 13 foreign investment,Footnote 14 migration,Footnote 15 national culture,Footnote 16 and cultural propertyFootnote 17 as matters of security.Footnote 18 These developments are emerging alongside, rather than replacing, classical security narratives around great power competition.Footnote 19 At the same time, transnational actors continue to offer alternative visions of security that either complement or contest these state policies. For example, a “second-generation human security” model makes pressing demands for “a very big allocation of resources, a far-reaching reform of global security capabilities, and a transformation in power structures.”Footnote 20 And the transnational social movements declaring that Black Lives Matter point toward alternative imaginations of security based on divestment from policing and carceral systems, and investment in communities.Footnote 21 All of these developments carry a similar demand for security, as well as an ambiguity about how that demand will be met.

This Article develops and applies a novel typology for analyzing the descriptive and normative implications of security claims in international law and politics. Security, as others have noted, is a deeply indeterminate concept, whose power derives not only from its association with particular issues or threats, but from the way that it combines fundamental ambiguity with a sense of heightened urgency.Footnote 22

This Article builds on this insight, arguing that actors take divergent approaches to security by issuing different—often implicit—answers to two questions: first, do experts hold a privileged position in identifying and describing security issues, and, if so, which experts’ views are relevant; and, second, should security be protected through the extraordinary means we ordinarily associate with the national security state, such as emergency powers and secrecy? Traditional militarist approaches to national security offer affirmative answers to both questions: security is a matter of military, intelligence, or diplomatic expertise, and is pursued through military force, surveillance, and similar means.Footnote 23 But any combination of answers to these two questions is possible, and each leads to a radically different approach to security in world politics.Footnote 24 So treating climate change as a security issue might, for example, lead us to think of security policy in terms of scientific knowledge and risk analysis—putting regulators in the driver's seat and triggering, rather than circumventing, the ordinary rule-of-law requirements of the administrative state.Footnote 25

Differing approaches to security, this Article argues, thus reflect a deeper struggle over whose knowledge matters when constructing and responding to the most pressing threats.Footnote 26 By using these variables to construct a typology, we can begin to disentangle the various approaches to security in international law and politics, and assess the desirability of each.

The typology developed here has four implications for the study of security in international law, which are by turns descriptive, normative, critical, and methodological. First, descriptively, this approach shifts our understanding of the security challenge to international institutions from one of conceptual uncertainty to one of epistemic authority and empowerment.Footnote 27 Recent international legal scholarship on security tends to privilege the conceptual dimension, suggesting that the fundamental challenge facing international regimes today comes from the expanding meaning of security and from the resulting uncertainty and scope for disagreement.Footnote 28 From this perspective, it appears critical that the international community achieve consensus on the right conception of security—that is, the conception that focuses our attention on truly the most dangerous threats and prioritizes them appropriately.Footnote 29 Once we reach this consensus, we might hope, then we can decide whether and under what circumstances an issue like climate change is “really” a matter of security rather than simply a matter of politics or policy.Footnote 30

However, if security is understood as a continuing struggle over epistemic authority, this desire for conceptual clarity may undermine, rather than enhance, our ability to accurately describe what is happening with security. To continue with the example at the outset of this Article, the struggle over whether and how to define climate change as a security issue implicates actors with diverse agendas. For instance, militaries may embrace climate security for their own purposes and to shore up their own authority, while resisting more transformative efforts that would place environmental scientists and regulators, or affected populations, at the center of security policy.Footnote 31 Thus we might see militaries embracing the idea that climate change threatens national security, while taking steps to describe that threat narrowly in terms of military readiness and armed conflict.Footnote 32 Approaches that focus on associating climate change with certain security labels rather than others (such as human security versus national security) risk obscuring rather than illuminating the ways that these labels themselves have become a terrain of struggle among various actors and agendas.

Second, as a normative matter, the typology developed here provides an initial guide, though no easy answers, to thinking about where we should position ourselves in these struggles. Judgments about security in international law, this Article argues, are unavoidably context-dependent, strategic, and political. This fact is in large part a consequence of the structure of international law itself. When a demand for security is projected into international politics, it does not encounter a blank slate: the international legal order is to a great degree organized into functionally differentiated subsystems—from human rights to trade to environmental law—which embed diverging assumptions about whose knowledge matters most in formulating policy and about the appropriate logic of policymaking.Footnote 33 Security can be deployed to entrench those existing knowledge practices and defend against challengers, but the power of security today also lies in its capacity for disruption—its demand to substitute a wholly new set of routines. Thus, the same arguments on climate security that might be used to justify and expand the Security Council's power to authorize force against “climate rogue states”Footnote 34 could also be used to disrupt trade rules that treat climate regulations skeptically as potential restraints on trade.Footnote 35 This dynamic is why it is often difficult to formulate a single stance on how security claims should interact with international law: if security is a tool for entrenchment or disruption, then it matters whose knowledge we are privileging, and how. The typology developed here thus provides a vocabulary for assessing the desirability of any given demand for security.

Third, by understanding security in terms of knowledge and authority, this Article raises critical insights concerning the structure of international law and politics. A key theme here is the struggle by non-state actors—whether overpoliced communities, Indigenous groups, small-scale food producers, or communities living near the sites of extractive industry—to have their own knowledge about their security interests recognized and prioritized as authoritative.Footnote 36 Achieving such recognition is particularly difficult in an international legal system that has historically privileged diplomats acting through foreign offices, or, more recently, networked groups of trained and recognized experts on a wide array of global problems.Footnote 37 This disconnect raises critical insights regarding the extent to which international regimes—even those that claim to uphold a humanized vision of security—remain undemocratic, unresponsive, and inaccessible.Footnote 38

Fourth and finally, this Article makes a methodological contribution by suggesting closer engagement between international law and critical security studies. International legal scholarship is steeped in three decades of dialogue with international relations scholars,Footnote 39 and international lawyers have drawn from both realist and constructivist traditions in security studies to interrogate a range of regimes and practices, from the use of force to cybersecurity.Footnote 40 But this interdisciplinary conversation has largely ignored or bypassed a range of critical traditions in security studies,Footnote 41 which for the past three decades have “re-conceptualized what security meant and how it mattered.”Footnote 42 As late as 2015, it was possible to say that most mainstream international law scholarship approaches security “without much reflection on theory or method.”Footnote 43 As international law is once again concerned with security, cross-disciplinary collaboration has the potential to enrich both disciplines by connecting critical security studies’ extensive reflection on concepts, theories, and methods to international lawyers’ deep knowledge of institutional structure and concern for the allocation of power and authority.

The Article proceeds in five parts. Part II situates the problem of security in international law, showing how security makes conflicting demands to either expand or preempt international legal rules. Part III sets out the core descriptive argument, showing how these demands become the terrain for deeper struggles over whose knowledge is relevant to constructing and pursuing security interests. This analysis produces two variables relating to the role of knowledge in any theory of security—that is, the identification of security issues, and the logic by which those issues are addressed—which can be used to categorize and evaluate competing approaches to security. Part IV uses these two variables to construct this Article's core analytical contribution: a four-part typology of approaches to security-knowledge, grounded in current debates in policy, law, and theory. Part V turns to a set of case studies in international economic law, demonstrating how conflicts among these approaches help explain current dynamics in the securitization of economic law. Part VI concludes by drawing out the implications of this study for further research on international law and security.

It should be noted that this Article was substantively complete prior to Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The Article does not, and cannot, purport to “make sense” of this unfolding tragedy. But the analysis developed here may offer a preliminary vocabulary for thinking about what we must prioritize—and whom we must empower—in whatever comes next.

II. International Law and Security Claims

Security makes claims on international law, though the precise nature and effect of such claims is almost always ambiguous. In itself, this does not distinguish security from any other deeply held value, but security occupies a special place in today's controversies owing to the intensity of security demands, and their problematic relationship with preexisting legal structures. National security, for example, is frequently described as law's vanishing point, wherein some or all of law's demands simply cannot be observed.Footnote 44 The UN Charter enables the Security Council to “decree” new law to preserve or restore international peace and security, described as the sine qua non of functioning government.Footnote 45 The concept of human security, though closely connected with human rights law and in principle less at odds with legality, is said to have the potential to “become a new organizing principle of international relations,” which reconceptualizes the territorial integrity of states and poses far-reaching challenges to international law.Footnote 46 At a high level of generality, a commonality among all these approaches is a sense of intensity or paramount importance, coupled with a demand to do something with existing legal arrangements—either to extend them or overcome them. It is useful to take each of these dimensions in turn.

First, security is a generative condition in international law—a basis for the creation or extension of legal institutions. This generative dimension is perhaps as old as the interstate system itself, providing a rationale to cede authority to a sovereign.Footnote 47 As Anthony Anghie points out, this conception of sovereignty emerged in the context of European colonization of the Americas, in a process that involved construing Spanish incursions as benign and Indian resistance as hostile, thereby justifying a limitless war of conquest.Footnote 48 As colonial control deepened, the purported needs of security justified the further extension of sovereign power through borders, blacklisting, detention, dispossession, and warfare.Footnote 49 Following decolonization, many former colonies traded formal sovereignty for more attenuated forms of control, either via economic sanctions or continued military presence justified on security grounds, or via state contracts and economic treaties meant to establish the security of foreign investments.Footnote 50 International legal doctrines sometimes facilitate these forms of indirect control, and at other times exert counter-pressure.Footnote 51

Security's generative capacity is also at the foundation of efforts to create and expand the powers of international institutions. Security lies at the foundation of the modern UN system,Footnote 52 and the UN Security Council enjoys broad authority under the Charter to take binding action for the maintenance or restoration of international peace and security.Footnote 53 This authority is a holy grail for actors seeking to leverage the international system because it enables the Council to take measures up to and including the use of force, which have legally binding effects and supersede all other inconsistent obligations.Footnote 54 Where the Security Council fails to act, regional organizations, such as the Economic Community of West African States, may become sites of innovation in this area.Footnote 55 Security can also provide a policy basis for creating new institutions and endowing them with exceptional powers, such as the power to arrest and prosecute individuals for crimes under international law,Footnote 56 or the power to take emergency action in the name of global health security.Footnote 57 And international human rights law affords a right to security that could support alternative security practices.Footnote 58

Second, “security” can signify the limited reach of a specific international agreement or a set of international rules.Footnote 59 Some international rules may include express carve-outs for matters of security, for situations of emergency, or for other extreme circumstances.Footnote 60 Many human rights treaties, for example, permit states to derogate from obligations in time of national emergency,Footnote 61 and some treaties contain additional carve-outs for security measures,Footnote 62 or impose potentially countervailing individual duties with respect to security.Footnote 63 Exceptions and carve-outs also appear in treaties relating to trade and investment,Footnote 64 digital commerce,Footnote 65 regional integration,Footnote 66 transnational law enforcement,Footnote 67 global health,Footnote 68 the law of the sea,Footnote 69 and nuclear non-proliferation.Footnote 70 At the drafting stage, states may attempt to design rules that provide flexibility for security measures,Footnote 71 and this perceived need for flexibility may generate demands for deference or for restrictive interpretations of the rules even when there is no express exception available.Footnote 72 The customary international law of state responsibility, while it does not speak of “security,” permits states to deviate from their obligations for reasons of self-defense, force majeure, or because doing so is necessary to safeguard an “essential interest.”Footnote 73 The concept of security may also limit international agreements in more indirect ways, such as by constraining the powers of international organizations.Footnote 74

These twin pressures to expand and contract cause considerable anxiety among international lawyers. The possibility that states will escape treaty obligations via security exceptions, or expand the powers of the Security Council by reference to new kinds of security interests, is frequently treated as a threat to the international rule of law.Footnote 75 Considerable scholarly effort is spent on how to limit the potential breadth of security exceptions through conditions on access, standards of judicial review, time limitations, or compensation requirements, either as a matter of treaty design or interpretation.Footnote 76 The extension of Security Council power into generally applicable legislation related to counter-terrorism activities revived an analogous set of inquiries into what, if any, inherent limits exist on the Council's Chapter VII power.Footnote 77

These important legal arguments should not be expected to settle longstanding questions regarding the relationship between international legality and security interests. To be sure, treaties can attempt to offer more precise definitions of security, and treaty drafters and interpreters can impose procedural conditions on the concept's invocation.Footnote 78 But there are strong reasons to think that at least some ambiguity around security is a feature, not a bug, of legal orders.Footnote 79 The label “security” is thus likely to remain a site of struggle, both within and among states, over who gets to define the most important interests of the day and how those interests are to be pursued.Footnote 80 The deliberate open-endedness of security at the conceptual level will also make it difficult to resolve these struggles definitively through interpretation, by, for example, settling on a single “ordinary meaning” of the term in legal disputes.Footnote 81 As the rules of treaty interpretation are themselves open-ended,Footnote 82 conflicts over interpretation often replicate, rather than resolve, political conflicts over who gets to define security and how.Footnote 83

III. Security-Knowledge in International Law and Politics

The foregoing discussion showed how the concept of security places demanding but ambiguous claims on international legal institutions. As a legal matter, such claims will have to be resolved by states, courts, and other actors according to the ordinary rules that apply to the interpretation and performance of international legal obligations.Footnote 84 Nevertheless, as discussed above, bona fide conflicts over interpretation may simply reproduce the ambiguity of security in any given institutional setting, and interpreters will have to make choices among multiple available meanings—choices that have political implications. This Part advances the Article's descriptive argument that, by cashing out and resolving security claims in this way, international legal institutions are implicated in deeper struggles over the role of knowledge in security policy.

International legal institutions shape understandings about whose knowledge matters in security policy in two ways. First, their decisions generate expectations about the kinds of expertise that are qualified to identify security issues. Second, legal instruments and decisions shape understandings about the sort of logic we expect security policy to follow. While this is not the only way to think about the stakes of security decisions, the focus on epistemic authority is particularly helpful for reflecting on the consequences of legal decisions and is likely to lead to more incisive analysis than focusing on competing conceptual definitions of security.

A. Knowledge of Security: Competence to Identify Security Threats

International law implicates the knowledge practices of security, in the first instance, by shaping expectations about whose knowledge matters for identifying potential threats. To illustrate how such choices work, consider President Trump's declaration that migration was creating a national emergency and security crisis at the southern border, which was made to obtain funding for a border wall, justify extreme and inhumane conditions of confinement, and threaten tariffs against Mexico.Footnote 85 If this measure were addressed in an international institution—such as a human rights treaty body or (if tariffs had been imposed) under a trade treaty—what kind of reasons should the United States have been expected to give in support of its policies?

It turns out there are several answers to this question, all of which appeared in the discourse reacting to the administration's policies. One response is to draw on the knowledge of former government officials and other experts in “national security and homeland security issues” to evaluate the supposed threat.Footnote 86 Perhaps this focus on national and homeland security is skewed, and we should instead center expertise on immigration itself.Footnote 87 Maybe our search for specialized knowledge about the supposed crisis should cause us to privilege the knowledge of those specially affected, such as the migrants themselves and local communities.Footnote 88 Or maybe this whole search is silly—any one of us can know that there is no emergency at the southern border, as surely as we can know the meaning of the word itself.Footnote 89 The debate over U.S. immigration policy involved references to all of these forms of expertise.

This slippage—from privileging national security experts to embracing wider forms of expertise—represents a spectrum of approaches to identifying security threats (see Figure 1 below). At one end of this spectrum is a relatively narrow cadre of elite security experts, often composed of current and former government officials who “have held the highest security clearances, and . . . participated in the highest levels of policy deliberations.”Footnote 90 A broader approach would emphasize a wider range of scientific expertise, such as public health or climate science. At the other end of the spectrum is a view that privileges knowledge of laypeople, on the ground that affected persons are best-placed to know their own security interests. Through various interpretive moves, legal institutions likewise shape expectations about which type of knowledge is most valuable in identifying and constructing security interests. The following examples demonstrate these dynamics at work in international law and politics.

Figure 1. Identifying Security Threats

1. Maintaining Closure: Drug Trafficking and Critical Infrastructure

In many regimes, there may be a strong preference against broadening expertise about security, and not merely to protect the special status of supposed security experts. A particularly salient example comes from the international human rights system's confrontations with the securitization of drug trafficking.Footnote 91 Some human rights treaties provide that states may deviate from specific obligations for “compelling reasons of national security,” such as the obligation to permit aliens subject to expulsion proceedings to challenge that expulsion.Footnote 92 One question concerning the expulsion of aliens is whether a state can rely on the security carve-out in cases where the alien in question is accused of drug trafficking.Footnote 93 Today, drug trafficking is widely considered a national security issue in policy statements and international instruments.Footnote 94 Thus, when a treaty uses a term like “national security,” it is difficult to argue that the ordinary meaning of this term per se excludes anti-trafficking efforts.Footnote 95 Whether this security interest ought to be recognized as a legal matter is another issue, and something courts and treaty bodies have been understandably reluctant to embrace.Footnote 96

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) confronted this question in C.G. and Others v. Bulgaria.Footnote 97 In that case, the applicant, a Turkish national who had resided in Bulgaria since 1992, was in 2005 summarily expelled without an opportunity to contest or obtain a lawyer on the ground he posed “a serious threat to national security.”Footnote 98 The government's evidence, provided to a reviewing Bulgarian court in a secret file, purportedly showed that the applicant was “member of a criminal gang dealing in illicit narcotic drugs,” though no specific facts were alleged in the public record.Footnote 99 The ECtHR's analysis focused on the Bulgarian courts’ application of the 1998 Aliens Act, which required the expulsion of aliens whose presence in the country “creates a serious threat to national security or public order.”Footnote 100 In this respect, the Court said:

It can hardly be said, on any reasonable definition of the term, that the acts alleged against the first applicant—as grave as they may be, regard being had to the devastating effects drugs have on people's lives—were capable of impinging on the national security of Bulgaria . . . .Footnote 101

While this statement appears at first glance to limit the conceptual scope of national security in a way that excludes drug trafficking, a deeper look at the case reveals that the decision's focus is instead on what kind of story the state was expected to tell. Indeed, the Court in this case expressly avoided any effort to interpret the term “national security” under Article 8(2) of the European Convention.Footnote 102 Instead, the Court focused all of its analysis on whether the expulsion had been “in accordance with law,” which the ECtHR has previously interpreted to require adherence to basic rule-of-law values like clarity and non-arbitrariness.Footnote 103 In other words, the Court was concerned not with whether drug trafficking fell within national security in the abstract, but with the fact-specific question of whether, in the context of this case, the applicant would have been on notice that the acts alleged by the state could trigger the national security provision in Bulgaria's 1998 Alien Act.Footnote 104 In this respect, the ECtHR emphasized that “the only fact” serving as a basis for the state's national security assessment was C.G.'s alleged involvement with a drug trafficking ring, and this showing fell short of the “specific facts” needed to show that the applicant presented a national security risk.Footnote 105

The judgment does not say exactly what “specific facts” Bulgaria should have been expected to show, but it does offer some clues. First, it will not be sufficient to establish that the person subject to expulsion proceedings broke the law: “run-of-the-mill criminal activities” are distinguished from those that threaten national security.Footnote 106 Second, it is not going to be enough that drugs or drug trafficking have “devastating effects . . . on people's lives.”Footnote 107 The state, in other words, could lard its expulsion orders with reams of testimony by law enforcement, public health professionals, and social scientists attesting to the illegality, dangers, and social impacts of drug trafficking, and it would likely make little difference. The Court indicated, however, that it might afford more deference where there are “serious potential consequences for the safety of the community.”Footnote 108 While the Court does not expressly say so, a state in Bulgaria's position would likely have been on much stronger legal footing if it had connected C.G.'s alleged drug trafficking activity to traditional military narratives about state security by adducing facts and testimony about impacts on regional stability, ties to non-state armed groups, or to international terrorism.Footnote 109 Although the ECtHR itself muddies the waters by talking about the “natural meaning” or “reasonable definition[s]” of security, this reading suggests the decision is less about whether drug trafficking is “in” or “out” of the security box than it is about how drug trafficking should be made to fit inside that box and, thus, who is sufficiently knowledgeable to make that fit.

None of these moves is particularly controversial in this context, and the point of this exercise is not to undermine the C.G. judgment. The criminalization of drugs is itself a challenge to human rights, and the securitization of the same is more dangerous.Footnote 110 On the contrary, a key point of this investigation is to show that, while opening security to a wider range of inputs and expertise may seem desirable, doing so has variable consequences in a fragmented and multilevel system, and many times closure is to be preferred. Still, the decision effectively leaves the door open to the securitization of drug trafficking by military or internal security officials, and in that way reinforces traditional militarized notions of security.Footnote 111

There are instances, however, where acts of epistemic closure are more troubling, or at least more contentious. In 2013 and 2014, two investors in an Indian multimedia company brought separate cases alleging that India violated its obligations under bilateral investment treaties by causing its state-owned enterprise to annul a contract for a satellite telecommunications spectrum.Footnote 112 For some years, the Indian armed forces had expressed concern that that the excessive lease of this particular spectrum—the “S-Band”—to commercial operators would impede national defense operations.Footnote 113 As an interagency process reviewed and ultimately annulled the satellite contract, the purported need for S-Band was broadened to include not just military and internal security needs, but also other “strategic” and “societal” needs, including railways, disaster management, tele-education, telehealth, and rural communication.Footnote 114 The ultimate decision annulling the contract cited both military and these broader strategic and societal needs.Footnote 115 In defense of its decision, India invoked the “essential security” exceptions in the relevant investment treaties.Footnote 116 Both cases were thus confronted with the question of whether and under what circumstances the protection of critical infrastructure can give rise to concerns under security clauses in investment treaties—an increasingly salient and thorny issue.Footnote 117

The tribunals’ decisions avoided ruling definitively on this question, while seeming to establish a strong presumption against including civilian infrastructure under the treaties’ security provisions. Both tribunals accepted in principle that military and internal security needs could be covered by the treaty provision, and both agreed that the other, more traditionally civilian uses were not covered.Footnote 118 The Deutsche Telekom tribunal, in particular, relied on the above-quoted language from C.G. v. Bulgaria, suggesting that to include issues such as disaster management, rural communication, railways, and tele-health would “distort[ ] the natural meaning” of the term “essential security interests.”Footnote 119 The tribunal added that the security clause could not be interpreted to include just any public interest, lest it swallow the treaty's requirement that states parties pay compensation for takings in the “public interest.”Footnote 120 The tribunal thus determined that the interests at stake must “go to the core . . . of state security” and “protect something of higher value than any ‘public interest’”—a function that it apparently associated with the military and national defense.Footnote 121 Indeed, both decisions are notably solicitous of the military and internal security agencies’ definitions of their own security goals.Footnote 122

The awards thus leave unclear the relationship between investment treaties and state laws designed to protect critical infrastructure and dual-use technology.Footnote 123 There are at least two possible readings of the decisions going forward. First, if the tribunals’ seemingly reflexive exclusion of civilian technology and infrastructure from the scope of “essential security interests” is read with maximum force, then the protection of those features could be entirely excluded from such clauses unless the relevant treaty is amended.Footnote 124 This would spell trouble for the many states that rely on similarly worded clauses to screen and control investments in a wide range of civilian projects deemed to be security-sensitive.Footnote 125 The second option is to focus on the lack of evidentiary support given by India to establish the security-sensitivity of the non-military interests, and to use these cases to suggest that such interests are not per se excluded but are subject to a higher burden of justification than the military's concerns.Footnote 126 Again, as in C.G. v. Bulgaria, the best strategy for triggering the treaties’ security clauses would likely be to show how the protection of such interests goes to the “core” of state security—likely by deploying military or military-adjacent expertise.Footnote 127 A consequence is that the best way to obtain greater flexibility internationally is to increase the authority of the military and defense establishment over industrial policy domestically.Footnote 128 In both cases, the integrity of the treaty regime is preserved at the cost of reaffirming the primacy of military and defense officials in defining what issues have a “higher value than [just] any public interest.”Footnote 129

2. The Struggle for Wider Expertise: Nuclear Weapons

Questions about the proper scope of security-knowledge do not just appear at the margins, as in drug trafficking or infrastructure cases, but plague even the assumed “core” instances of military and defense matters. Consider the question of nuclear weapons and deterrence—perhaps the sine qua non of twentieth century national and international security policy.

The dominant mode for framing nuclear weapons since 1945 has been in adversarial terms, focusing on the threat posed by the actors in possession of those weapons, their incentives and motivations.Footnote 130 As Emmanuel Adler documents, American policy on nuclear deterrence in the 1960s came increasingly under the influence of an “epistemic community” of civilian strategists and nuclear scientists, along with their partners in government, who advocated for arms control.Footnote 131 These experts’ ideas about nuclear policy, premised on concepts drawn from game theory,Footnote 132 shaped U.S. national security policy and international legal regimes for decades.Footnote 133 As understandings about nuclear policy shifted to a greater concern with proliferation and “rogue” actors,Footnote 134 the shape of the legal regime shifted, including with a turn to multilateral sanctions under Security Council authority.Footnote 135 These approaches represented new sets of cultural understandings, and opportunities for new forms of knowledge-creation.Footnote 136

There is, however, another way to describe the danger posed by nuclear weapons, and that is to focus on the explosion itself, rather than the government wielding it. By this logic, it is the very existence of nuclear weapons, rather than the possibility of surprise attack or the supposedly unsteady hand of a rogue state, that is destabilizing.Footnote 137 An accidental detonation of a nuclear device, for example, poses an equivalent danger to the launch of a nuclear weapon.Footnote 138 The relative absence of such concerns in academic and policy circles, as compared with the focus on deterrence and proliferation, suggests a privileging of certain forms of expertise and knowledge-creation, and opens the possibility that other forms of knowledge could be applied to identify and frame the nuclear security threat differently.

This question—who has the competence to identify security threats—emerged as a critical issue in the Legality of the Use by a State of Nuclear Weapons in Armed Conflict case. In that case, the World Health Assembly (WHA) requested an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on whether the use of nuclear weapons in armed conflict would violate obligations under “international law, including the [World Health Organization (WHO)] Constitution.”Footnote 139 The WHA is the plenary body of the World Health Organization, which has as its objective “the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of health.”Footnote 140 Member states’ delegations “should be chosen from among persons most qualified by their technical competence in the field of health, preferably representing the national health administration.”Footnote 141 The WHA resolution requesting an advisory opinion accordingly stressed the connection between health and the use of nuclear weapons, suggesting these fell within the WHO's competence.Footnote 142 The resolution specifically borrows language from public health to discuss the nuclear weapons threat, stating that “primary prevention is the only appropriate means to deal with the health and environmental effects of the use of nuclear weapons,” and that this required clarification of their legal status.Footnote 143

This request was immediately controversial.Footnote 144 The ICJ in 1995 decided it could not address the substance of the request, finding that the legality of nuclear weapons was not “within the scope” of the WHO's activities.Footnote 145 The Court took particular aim at the “primary prevention” rationale, finding that, while the WHO might assist in averting nuclear war by disseminating information on its adverse health effects, the “political steps by which this threat can be removed” were clearly above the organization's pay grade.Footnote 146 While the WHO has “wide” responsibilities in “sphere of public ‘health,’” there was “no doubt that questions concerning the use of force, the regulation of armaments and disarmament are within the competence of the United Nations and lie outside that of the specialized agencies.”Footnote 147

Judge Weeramantry, in dissent, criticized the Court's conclusion that the “WHO's function is confined to health, pure and simple, and it strays into unauthorized fields when it enters the area of peace and security.”Footnote 148 His dissent emphasizes the overlap between matters of health and international security, and can be read as a strong statement of the broad approach to security that was emerging in international politics at the time.Footnote 149 “I cannot subscribe,” Judge Weeramantry writes, to the view that the preeminent body in global health should sit idly by “for the technical reason that it would be trespassing upon the exclusive preserve of the Security Council, who are the sole custodians of peace and security.”Footnote 150

The divergence between the Court majority and its dissenters thus reveals yet another dimension to this well-known opinion.Footnote 151 There was no doubt that a great deal of legal and diplomatic practice existed with respect to the proliferation and use of nuclear weapons.Footnote 152 The underlying policy question in the WHA case was whether an organization, whose delegations are composed of health ministers and whose secretariat is staffed by public health experts, should have anything to say about how to meet the defining security threat of the century. The Court answered that it did not, suggesting that the WHO's role was limited to addressing the health-related fallout of nuclear war. But an alternative approach was possible, and the WHO's embrace of a concept and legal framework for “global health security” in the 2000s suggests that times may have already changed.Footnote 153

3. The Lay Public: “New Wars” and Food Crises

In many international legal fora where security claims play out, there are only limited opportunities for those most directly affected to define their own security interests. States are ordinarily represented internationally by their executive branches, which have incentives to define security interests in their own terms, sometimes to the exclusion of other domestic authorities. While international parliamentary institutions, consisting of either directly elected representatives or delegates from national legislatures, are relatively common in today's international organizations, these institutions generally lack significant power to shape policy or bind either member states or international organizations themselves.Footnote 154 The representation of non-specialist, non-state interests in global government, to the extent it exists, is most often accomplished through various mechanisms for NGO, civil society, or “multi-stakeholder” participation.Footnote 155 Nevertheless, there are some areas where international legal regimes have enabled lay publics to struggle over and potentially define their own security interests.

First, Christine Chinkin and Mary Kaldor note some halting progress in international law and practice toward prioritizing local knowledge and “local ownership” in the formation of peace agreements.Footnote 156 Historically, peacebuilding had been a top-down affair, which can privilege the perspective of governments, interested third states, and transnational experts to the exclusion of local communities.Footnote 157 As Séverine Autesserre writes, these top-down projects often replicated colonial dynamics, even as the international experts involved in the peace-building process would have emphatically denied doing so.Footnote 158 The early twenty-first century, however, has witnessed a “local turn” in the scholarship and practice of peacebuilding.Footnote 159 This is reflected in several key normative statements at the United Nations, which emphasize the formal or informal participation of civil society groups, and particularly women, in the peacemaking process.Footnote 160 Implementation of the local turn is, in many observers’ views, spotty at best, but Chinkin and Kaldor do note some promising precedents in the 2004–2005 peace process in Darfur and the 2003 Liberian peace deal, where civil society organizations and women's groups played a formal role in the peace process.Footnote 161 These precedents echo struggles in other areas, such as disaster response, where there is both a normative imperative and a series of practical and political obstacles to centering the role of local communities in restoring peace and security following a period of crisis.Footnote 162

A second site for innovation and lay participation can be found in the area of food security.Footnote 163 While “food security” has its own logic and conceptual framework, it also interacts in complex ways with other national, global, and human security discourses.Footnote 164 The Committee on World Food Security, as extensively reformed in 2009 following the global food price spike that began two years earlier, has emerged as a “unique space,” which enables those most directly affected by food insecurity to “have direct influence in global policy coordination.”Footnote 165 Pursuant to the 2009 reforms, civil society organizations and NGOs were empowered to establish their own mechanism for facilitating consultation and participation in the body;Footnote 166 most strikingly, as Michael Fakhri observes, this new “Civil Society Mechanism” has privileged the voices of social movements and peasants’ groups over international NGOs.Footnote 167 While the Committee's place, and civil society's role, in global food policy is contested and far from secure, there appears to be broad agreement that the participation of civil society organizations “served to expand debate, introduce new perspectives and therefore shift the direction of global food security policy.”Footnote 168 The Committee's engagement with civil society thus serves as a “benchmark” for an alternative vision of security-knowledge in global politics.Footnote 169

The foregoing examples, while specialized and partial, suggest alternative mechanisms for producing knowledge about security. These fora are not closely tied to national security establishments, but neither are they embedded in the wider claims to expertise that characterize most other international organizations. Here, instead, is an approach to security that, as in Rana's counterintuitive reading of Hobbes, “is fundamentally egalitarian and thoroughly rejects any distinction between elite and ordinary rationality.”Footnote 170 Notably, however, in international legal settings these sources of lay knowledge must address themselves to, and reconcile themselves with, the still-dominant discourses of international security, diplomacy, and technocratic expertise.Footnote 171 This tension underscores the extent to which security in international politics remains the province of elites, even if the sources of elite knowledge can sometimes be expanded to embrace a wider range of disciplines and expertise from time to time.

B. Knowledge in Security: The Logic of Security Policy

Once a security issue is identified, the question turns to how expert or lay knowledge will be deployed to address it. This question, which concerns the logic of security policy, is a central concern, particularly in judicialized international systems today.Footnote 172 At one end are doctrines of “public reason”—devices like proportionality, reason-giving, means-ends rationality, and publicness, which force states to justify any policies that burden human rights, trade, or property.Footnote 173 At the other extreme is the idea that legal institutions, whether national courts or international tribunals, have no place second-guessing a national executive's action to protect the country's security interests. Rather than belonging to the realm of reviewable and intelligible public reason, such judgments are, in words recently resurrected by the U.S. Supreme Court, “‘delicate, complex, and involve large elements of prophecy.’”Footnote 174 This tension, between public reason and prophesy, is well-known in the study of security exceptions and international law.Footnote 175 But these doctrines also have implications for whose knowledge matters in security policy, which have gone undertheorized.Footnote 176

One of the major, field-spanning developments in post-Cold War international law has been to subject state policymaking in various domains to requirements of rationality and reason-giving.Footnote 177 International legal regimes from trade to human rights have developed robust requirements of consistency, ends-means proportionality, scientific rationality, and publicity in their review of national decision making.Footnote 178 For example, when a state adopts a public-health measure that negatively affects foreign investors—such restrictions on marketing for tobacco products—a tribunal will ask whether and to what degree the measure is rationally related to the pursuit of its health objective.Footnote 179 Even where a treaty appears to preclude this kind of inquiry by reserving substantial discretion to the state, courts, tribunals, and other bodies might still review the procedure by which those aims are addressed.Footnote 180 As the level of required scrutiny increases, these forms of process and rationality review shift power from elected officials and political appointees, and toward the scientists, experts, and lawyers that staff government bureaucracies.Footnote 181

Security decision making, the traditional view goes, resists the demands of public reason and tends toward prophecy. Security is said to demand a degree of “decision, activity, secrecy, and dispatch” that is inconsistent with the broad, open-ended debates of ordinary politics.Footnote 182 Security decision making is also resistant to the demands of scientific and procedural rationality: it is recognized as being ad hoc, subject to demands of expediency, and not necessarily amenable to the requirements of reasoned consistency and publicness that attend ordinary government regulation.Footnote 183 Expertise is still required—indeed, contemporary security policy is replete with recognized and self-appointed experts clamoring to be heard on everything from migration to climate change.Footnote 184 But on one standard account, security expertise is an amalgam of judgments about what is prudent, expedient, or possible, and in that respect it is not easily compared to the kind of expert knowledge that is imagined to support ordinary, science-based regulation. It was this conception of security, for example, that appeared to animate the U.S. Supreme Court's 2018 decision upholding a travel ban against claims of anti-Muslim bias, reasoning that any rule “‘that would inhibit the flexibility’ of the President ‘to respond to changing world conditions should be adopted only with the greatest caution,’ and our inquiry into matters of entry and national security is highly constrained.”Footnote 185

In international law, the tension between expertise and prophecy can be framed, but not fully resolved, by the text of the relevant legal instruments. Some treaties, for example, may offer guidance as to how tightly a particular policy must be related to an articulated security objective, and some also indicate the level of deference to be afforded by a reviewing court.Footnote 186 Still, these texts do not resolve the question, and under each of these regimes security demands still face competing pressure toward public reason and prophecy. Even where the law does not explicitly demand deference at all, institutions often feel pressure to implicitly soften their standards of review when it comes to security measures.Footnote 187 Standards like “necessary,” or even the “only way” requirement of customary international law, can be ratcheted up or down through legal interpretation.Footnote 188 Where treaty law appears to grant wide discretion, interpreters have relied on customary international law,Footnote 189 general principles of law,Footnote 190 jus cogens norms,Footnote 191 or the law of the reviewing tribunalFootnote 192 to ratchet up the level of scrutiny.

These varying degrees of scrutiny have implications for whose knowledge matters in security policy and how that knowledge is deployed. The capitulatory approach, where legal institutions abstain in the face of security measures, amplifies the significant power that executive agencies enjoy in the national security state. Stricter forms of review, such as “hard look” review or strict necessity and proportionality, seek the “progressive submission of power to reason.”Footnote 193 This view shifts power from political to legal, scientific, and technocratic forms of expertise, promoting evidence-based policy but raising questions about the suitability of having technocrats choose between competing values.Footnote 194 A middle approach—sometimes referred to as a “suitability” or “rational basis” test—is limited to ensuring a relationship exists between the policy goal and the measure pursued.Footnote 195 This approach expands the space in which legislators and political appointees can work, giving them broad scope to define and pursue policies, while ensuring that policies pursue publicly defined goals subject to political accountability.Footnote 196 The implications of these approaches are depicted below in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Responding to Security Threats

By framing these techniques in terms of epistemic authority, we can see how different approaches might be valued in different circumstances. In some circumstances, such as C.G. v. Bulgaria, it may make sense to push toward rationalization in a way that empowers lawyers to tailor security policies to minimize the burden on civil liberties.Footnote 197 But, more generally, it is open to question whether and to what extent international law should empower bureaucratic experts over political actors. In many cases, it may make sense to ratchet review downward to give full scope for political debate, struggle, and compromise—thus empowering lay forms of knowledge—even if the results cannot be fully justified on rationalist terms.Footnote 198 Even minimal demands for rationality can be troubling when they are used to entrench elite forms of knowledge or outdated notions of security against possible contenders whose politics may appear unruly. For example, some tribunals have shown an unexamined distrust of “politically motivated” policies, treating these as non-rational.Footnote 199 In such circumstances, a turn toward strong, even self-judging exceptions may be a useful means to disrupt established routines and press for transformative change.Footnote 200

IV. Four Approaches to Security, Knowledge, and International Law

The foregoing analysis indicates why, when international lawyers speak about “security,” we are often talking past each other. To take the example from the outset of this Article the characterization of climate change as a security threat potentially suggests a wide range of meanings and approaches to security, including the elevation of science and environmental expertise, or the encroachment of the military into climate policy.Footnote 201 Though potentially clarifying, it does not fully answer the question to suggest that climate policy is a human or international security issue as opposed to a national one, because these vocabularies can also be associated with a range of approaches from community empowerment to military humanitarianism.Footnote 202 A more robust discussion of the merits and demerits of securitizing climate change, or any other issue, demands that we take apart the constituent parts of security itself, to see how they might be scrambled and reassembled. The previous part made the case that the power of security lies to a large degree in the way in which it vindicates competing claims to epistemic authority. This Part uses that insight to build a framework for understanding and analyzing security claims and their impact on international law.

To that end, this Part sets out a four-part typology of approaches to security. These types are developed from actual historical and social practices of security but are designed to be sufficiently abstracted to enable comparisons and analysis across particular situations.Footnote 203 Such a typology thus exists at some remove from the actual, far messier reality of history, and few actual instances of security are likely to easily conform to any one particular type. It is hoped that whatever is lost in terms of strict fidelity to history will be gained by enabling comparative analysis across time, space, and regime, but the usefulness of this classification can in the end “only be judged by its results in promoting systematic analysis.”Footnote 204 Note that this typology is not meant to provide either a comprehensive or exhaustive discussion of all possible approaches to security,Footnote 205 nor are the citations here meant to firmly associate the scholar cited with the ideal-typical frame being put forth.

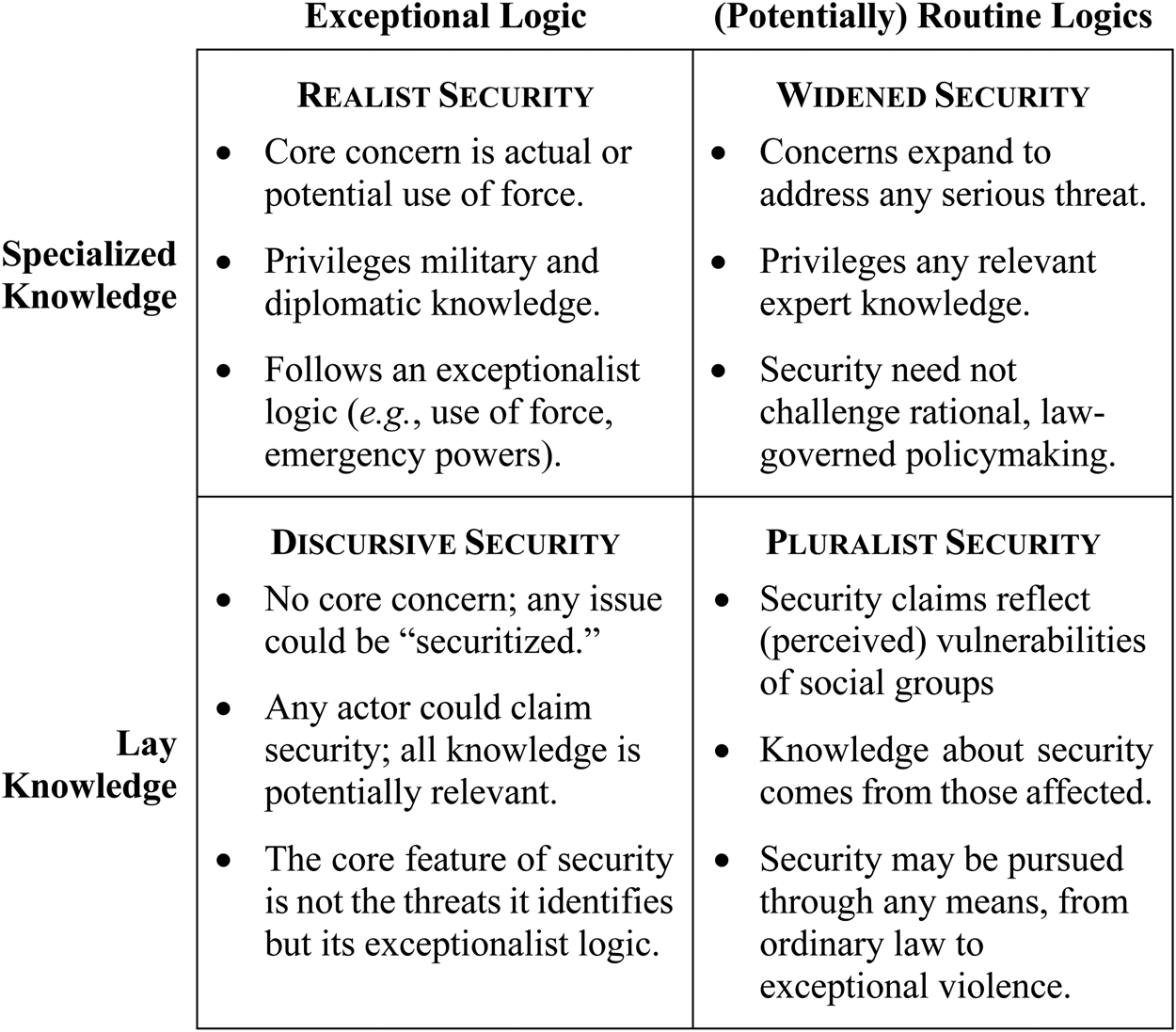

Figure 3, above, introduces each of the types developed in this Part, and compares their views of how knowledge about security is developed and put into practice. The top row refers to approaches that rely on some form of specialized knowledge to identify security threats: for realist security, as I define it, this means primarily military knowledge; for widened security, threat identification is open to a wider range of expertise. The bottom row of Figure 3 contains theories that embrace, at least in principle, a despecialized approach to framing security issues: discursive security, drawing on the Copenhagen School of security studies, accepts in principle that anyone can attempt to securitize an issue, though in practice political elites are more readily able to do so; pluralist security expects that threats will be constructed on the basis of shared and emergent identities, rather than according to some expert logic. Realist and discursive security, in the left-hand column, are united in their view that security is fundamentally associated with extraordinary measures, such as emergency power, secrecy, or violence.Footnote 206 Widened and pluralist security are distinguished, on the righthand side, as having no necessary connection to extraordinary measures, though these are not strictly ruled out either.

Figure 3. Four Views of Security-Knowledge

Each of these types is designed to be primarily descriptive—a way to identify, categorize, and analyze existing statements about and practices of security—but these types have both normative and forward-looking implications. First, by suggesting how security policy is likely to unfold, each type is likely to provoke in us a normative intuition about how widely the security frame should be deployed. For example, if security policy empowers military officials to classify the world and pursue threats through force and emergency powers, then many of us would likely want its deployment to be strictly limited.Footnote 207 Second, as the following discussion emphasizes, each type is inherently dynamic, in the sense that it contains elements that, if rigorously applied, open doors to the alternative approaches to security reflected in the remaining types.Footnote 208 The four types described here are thus not stable equilibria but rather more like quantum states, in which each type contains the potential for the others. This dynamism is reflected in actual practice,Footnote 209 and underscores the extent to which our understanding of the grammar and logic of security can be only a first step toward formulating a normative position in any concrete case.

A. Realist Security

The first approach identified here identifies security primarily with the use or non-use of military force. The term “realism” is used here to reflect the affinity with Kenneth Waltz's argument that security, defined as state survival, “is the highest end” among the infinitely varied world of possible national interests.Footnote 210 Survival, moreover, is in the (neo-)realist tradition frequently associated with use, threat, and non-use of military force.Footnote 211 On this view, security is used primarily to signify the defense of states against destruction or destabilization by force, either coming from outside or within.Footnote 212 This close connection between force, statehood, and security remains influential on interdisciplinary scholarship in international law and politics.Footnote 213

The focus on the use of force here centers military knowledge, alongside shifting sets of civilian expertise that support the security establishment, in the definition of security threats and issues. The U.S. security establishment, as it developed during and immediately after the Cold War, offers an example of this approach to security knowledge. Prior to World War II in the United States, military affairs were largely the province of professionals, and civilian involvement in strategy and military planning were discouraged.Footnote 214 This changed with the emergence of the concept of “national security” during the war, which, as Dexter Fergie points out, was from the beginning bound up with civilian expertise—exemplified by the “hordes of social scientists who contributed their expertise to the war effort.”Footnote 215 The emergence of nuclear deterrence as a primary security concern during the Cold War led for a time to the ascendance of game theory and quasi-economic modeling as an adjunct to security policy.Footnote 216 As U.S. security concerns shifted in the 1990s to concerns about internal strife and “resource wars,” new forms of expertise were incorporated into the security and defense establishment.Footnote 217 A similar shift happened again after 2001, as U.S. policy refocused on international terrorism and state-building.Footnote 218 In each of these examples, a broad range of expertise is attached to the security and defense establishment for the purpose of aiding the military and intelligence agencies in identifying and framing potential security threats. The military and security establishment thus remains at the center of the process, with other forms of knowledge performing a critical but adjunct role.

When it comes to the logic of decision making, the default mode for realist security is raison d’état. On this view, requirements of legality, publicity, and rationality may yet be appropriate for a wide range of issue areas or circumstances. But where (national) security is threatened—as in an emergency—courts, legislators, and other actors have “no real choice but to hand the reins to the executive and hope for the best.”Footnote 219 The typical legal controls for non-arbitrariness, reason-giving, and factfinding will be suspended, or dialed so far down as to be meaningless.Footnote 220 This is because the national security bureaucracy, headed by the executive, is alone thought to possess the secret knowledge, capacity for efficient action, or political legitimacy to address urgent and existential threats.Footnote 221 The connection between this rationalist view of international affairs and the treatment of security policy as ad hoc, improvisational, and not amenable to review or publicity is historically contingent rather than logically necessary.Footnote 222 Indeed, while the justifications for such deference are often premised on the expertise of the national security establishment, this flexibility also creates substantial space for the influence of professional norms, ideology, bias, and racial or religious animus.Footnote 223 Nevertheless, this view of security logic remained popular among those who came to theorize security after the attacks of September 11, 2001.Footnote 224

We can see the union of these two variables—military-centered knowledge and raison d’état—in arguments that claim wide latitude under international law for national security policies. For example, in a recent case brought by Iran under a 1955 commercial and consular treaty, the United States defended its reimposition of economic sanctions against Iran on the ground that the sanctions were necessary to protect its essential security interests.Footnote 225 The United States’ arguments in this pending case have emphasized the fact that this “core national security decision was made at the highest levels of the U.S. Government, following a National-Security-Council-led review of the United States’ policy toward Iran.”Footnote 226 The United States has further emphasized that the treaty's security exception “provides wide discretion for a State to evaluate and determine what measures are necessary to protect those essential interests,” and that its corresponding burden to justify those measures internationally is low.Footnote 227 This position reflects a view that “core national security tools” are subject to limited oversight by the economic treaties at issue, and affording maximum flexibility to the national security establishment is preferable to close judicial scrutiny.Footnote 228 As of this writing, the ICJ has yet to rule on the merits of this defense.Footnote 229

As this example suggests, those adopting something close to the ideal-typical vision of security knowledge—including various strands of realist thought and so-called traditional security studies—are likely to counsel modesty for both security and for law. As to the former, realist security recognizes that the pursuit and defense of security is bloody business not to be widely extended.Footnote 230 By limiting international security to “core” matters of military affairs, realism arguably can be deployed to reject the conceptual apparatus that has justified the expansion of military affairs into nearly every corner of domestic and international life.Footnote 231 In international law, this sense of modesty is reflected in calls to refocus international institutions like the Security Council on narrower conceptions of “international peace and security” that are centered on interstate conflict.Footnote 232 Such approaches are suspicious of the mobilization of military force for humanitarian intervention, regime change, or democracy promotion, emphasizing the folly of these military adventures and their cost in terms of human life and security.Footnote 233 This caution, however, should not be confused with a radical commitment to peace.Footnote 234

Equally, we should expect modesty when it comes to what law might accomplish with respect to “real” security interests.Footnote 235 Military force will sometimes appear necessary, and it is unlikely that law will do much to constrain that possibility.Footnote 236 We should therefore recognize that security—in its core, military-focused sense—is likely to work as an implied, de facto limitation on the effectiveness of international legal regimes.Footnote 237 Realism may also be congenial to narrowly framed treaty-based exceptions that generally embed states in a relatively thick set of international rules vis-à-vis allies, but offer states a free hand to pursue security competition with adversaries.Footnote 238 At the same time, realist security would be skeptical of attempts, whether by neoconservatives or human security advocates, to expand the notion of security to encompass issues like human rights violations, and potentially to justify military responses thereto.Footnote 239 Realist thinking, however, offers fewer critical remarks about the expansion of security concepts to extend hegemonic power through international organizations, such as the use of Security Council authority to extend the reach and effect of U.S. sanctions, with minimal legal oversight.Footnote 240

This ideal type, however, contains internal tensions, which tend to drive it toward any one of the other three types discussed below. Even in its most military-focused sense, security as an academic discipline and political practice has always been inherently interdisciplinary, inviting other forms of expertise to perform adjunct roles.Footnote 241 This interdisciplinarity raises the possibility that those other forms of civilian and political expertise might become dominant, shifting the relevant knowledge and logic of security away from military affairs or from exceptionalism.Footnote 242 More radically, as Rana points out, realism's exceptionalism suggests that, in truth, “no science or expertise of security exists,” pointing the way to a radically democratic approach that supplants experts with the lay public.Footnote 243 These possibilities are explored in the following Sections.

B. Widened Security

Set against realist security are various approaches that seek to expand security into new realms and decenter the role of military affairs. Many of these approaches find their roots in an intellectual and policy-oriented push in the 1980s, which accelerated after the end of the Cold War, to “broaden” and “deepen” the concept of security.Footnote 244 A key theoretical development in this period was the rise of feminist security studies, which, among many insights, showed how threats to women's security can come from their own states and state security forces, as well as from non-military threats such as inadequate access to health care or birth control.Footnote 245 These approaches scored some political successes, including the adoption at national, regional, and international levels of documents relating to human security,Footnote 246 global health security,Footnote 247 and women, peace, and security,Footnote 248 among others. At the same time, states reformulated their national security policies over the first two decades of the twentieth century to increasingly address non-military threats, though not always with results that human security advocates would have endorsed.Footnote 249 The “broadening and deepening” debates have produced a complex field with a wide range of approaches to security, which cannot be reduced to a single conception or ideal type.Footnote 250 Each of the remaining three types discussed here owes a debt to those debates.

One type that emerges from these debates, which has gained traction in mainstream security circles and even in some state policies, is referred to here as widened security. This view has sought to dislodge military affairs from their central role in security policy, and argues that today's most deadly threats, such as climate change and pandemics, do not come from any foreign or domestic adversary,Footnote 251 and instead are made intelligible through the application of scientific expertise.Footnote 252 Nevertheless, the widened-security view, as described here, remains reliant on state-based structures to ensure security, and is likely to count diplomacy, lawmaking, and regulation high among its list of tools.Footnote 253 This distinguishes the approaches described here from those that focus on “deepening” security by going beyond the emphasis on states in the international system.Footnote 254

This widening view finds echoes in the Obama administration's national security strategies,Footnote 255 and has enjoyed a revival of mainstream interest since the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, at the height of the pandemic, Oona Hathaway wrote:

[W]e should broaden the lens of national security to think about all serious global threats to human life. Terrorism should be a part of the conversation, but it should be considered next to other, more pressing threats to American lives, including pandemics, other public health threats, and climate change. The assessment of threats should be based on scientific assessments of real global threats that require serious global solutions. That's what “national security” must mean in the post-COVID-19 world.Footnote 256

While this comment explicitly refers only to knowledge of security threats, its assertion that threat assessment must be based on scientific evidence also has implications for the logic of security policy. By yoking threat-assessment to the full range of available scientific expertise, this approach narrows if not eliminates the distance between security policy and the ordinary rationality requirements of the administrative state.Footnote 257 There is also the possibility that a more rationalized and reviewable security policy could emerge even in more “classical” domains of war-fighting and counter-terrorism.Footnote 258 Perhaps, for example, the securitization of the environment has promoted alternative “security practices based on prevention, risk management and resilience,” while challenging the close association between security, emergency, and exception.Footnote 259 Likewise, the close association between human security-style approaches and human rights law suggests a preference for proportionality and rule of law values over exceptionalism.Footnote 260

Despite its limited institutional successes, this type, too, is unstable. First, widened security can collapse back into forms of realism if these new security interests like climate and health become militarized.Footnote 261 For example, Diane Otto has argued that the “women, peace, and security” frame has in a sense become a victim of its own success, as it has “become captive to the militarized security frame” that typically characterizes Security Council action.Footnote 262 Second, as actors turn to exercising extraordinary legal powers to address these new security threats, widened security's claim to preserve a place for legality and rationality in security policy becomes increasingly tenuous.Footnote 263 Here, climate change is a relevant example: where it was once possible to say that the climate policy was still “designed and developed in the realm of ordinary policy debate,”Footnote 264 this assumption arguably no longer holds as actors are increasingly considering the use of emergency powers to pursue climate policy.Footnote 265 Finally, the increasing pluralization of expertise in determining security threats suggests, consistent with many “deepening” approaches to security, that lay knowledge rather than expertise does, and should, drive security policy.Footnote 266 The latter two possibilities are taken up below.

C. Discursive Security

In contrast to each of the above frames, which privilege expertise and specialized knowledge for identifying security threats, an alternative view emphasizes the irreducibly political character of such determinations. One such view is readily captured for our purposes by what is known as securitization theory.Footnote 267 This approach, developed by the so-called Copenhagen School of Security Studies, emphasizes the fundamental and irreducibly political character of claims to know something about security.Footnote 268 Security, on this view, is not necessarily associated with any particular threat (e.g., military invasion), or any particular object (e.g., securing the state).Footnote 269 Rather, security is a discursive practice wherein some actor identifies something as an existential threat, and argues that the threat requires an extraordinary, and perhaps extra-legal, response.Footnote 270 As these moves gain acceptance, an issue is “securitized,” meaning it is transferred to the realm of extraordinary measures and left outside ordinary politics.Footnote 271 This association with exceptionalism makes the theory inherently wary of security, arguing that “desecuritization is the optimal long-range option,” because it moves issues “out of th[e] threat-defense sequence and into the ordinary public sphere.”Footnote 272

When framed this way, the insights of securitization theory are compatible with a set of intuitions about security-knowledge that are likely to be held by many international lawyers.Footnote 273 First, as noted above, security is an indeterminate concept, whose meaning and content at any given time is socially and politically constructed.Footnote 274 On this view, we can acknowledge the privileged position that elites—such as politicians, bureaucrats, officials, lobbyists, pressure groups, and, increasingly, scientists—hold over the definition of security issues, just as the aforementioned types do.Footnote 275 But at the same time we can recognize that the moment of securitization itself is not determined by that expertise, and instead reflects a move that belongs to politics and narrative.Footnote 276 Second, despite being radically open to redefinition, lawyers might intuitively agree that security has a troubling historical connection to emergency powers and exceptionalism.Footnote 277 Third, this link to exceptionalism suggests a normative orientation that, like many public lawyers, is skeptical of security claims, and prefers the long-term desecuritization of issues.Footnote 278 The likelihood that security claims will be fused with demands for secrecy, emergency power, extra-legalism, military force, etc., places a thumb on the scale against such claims, even if the desirability of using the security label can never be fully resolved in the abstract.Footnote 279 Together, these insights are broadly compatible with a liberal-constitutionalist spirit that seeks to limit the abuse of security claims and provide offramps back to normal politics, even if that liberal spirit was not the intention of the theory's progenitors.Footnote 280

This set of insights is broadly compatible with the ways that international lawyers have addressed derogations from internationally recognized human rights. Many human rights treaties include derogations provisions allowing states to “suspend certain rights during emergencies while subjecting such measures to international notification and monitoring.”Footnote 281 The substantive scope of what might constitute an “emergency” is open ended, and in practice these provisions have been applied to war, insurrection, terrorism, economic crises, natural disasters, and COVID-19.Footnote 282 Once this threshold is reached, a public emergency can justify suspensions of rights otherwise ordinarily guaranteed in a liberal democratic society, subject to reporting and monitoring requirements, as well as substantive requirements of proportionality.Footnote 283 By encouraging states to channel their exercises of exceptional power through the derogations system's procedural framework, human rights treaties force officials to make “public assertions about the nature of the crisis and the scope and duration of emergency restrictions,” which can provide benchmarks for public pressure if those are later exceeded.Footnote 284