Birth of an Idea

In a remote canyon in Mesa Verde National Park (MVNP), southwestern Colorado, USA, a small group of living and dead Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii [Mirbel] Franco var. glauca [Beissener] Franco) trees exhibit unique features. In 1954, park archaeologists James Allen Lancaster and Don Watson suggested, in unpublished correspondence, that those morphological attributes were evidence of precolumbian stone-axe cutting of limbs on those Douglas-firs. In 1965, archaeologists Robert Nichols and David Smith built on those assertions and went further, arguing that the trees preserved evidence of precolumbian forest-management practices in a place now called Schulman Grove (Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Location of Schulman Grove, Navajo Canyon, MVNP, southwestern Colorado. (Image drawn by Erin Baxter.)

In this article, we attempt to replicate Nichols and Smith's (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) results through a (re)analysis of archived and recently collected tree-ring samples and a controlled analysis of archived and published records. In order to replicate their results, we expect three lines of evidence to collectively and independently point toward the presence of human agency in the development and growth of trees in Schulman Grove: (1) incontrovertible morphological evidence of stone-axe cuts on the trees and limbs in question, (2) verifiable and replicable tree-ring dates derived from those trees using modern chronologies and analytical techniques, and (3) concordance between tree-ring dates at Schulman Grove and tree-ring dates from secure archaeological contexts in cliff dwellings and other structures at MVNP.

Background

On November 19, 1954, Watson wrote to dendrochronologist Edmund Schulman of the University of Arizona's Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research (LTRR) to inform him of the discovery of an unusual Douglas-fir tree growing in a small north-facing slope in Navajo Canyon, MVNP (Figure 1). As Watson wrote, the tree “has the stubs of three branches which were cut off with stone axes” (Watson to Schulman, letter, 19 November 1954, Mesa Verde National Park [MVNP] Archives, Wetherill Mesa Archaeological Project [WMAP], RC-4-K4, Box 11, “Dendrochronology”). Watson's letter, and Schulman's excited reaction to it, refers to the “Lancaster Old Tree – 1” (LOT-1; see discussion below) and marks the first time that Southwest archaeologists and dendrochronologists postulated the presence of precolumbian stone-axe-cut stumps, stubs, or limbs still being preserved in a modern conifer forest.

The correspondence between Schulman and MVNP archaeologists goes back and forth from 1954 to 1958. On January 8, 1958, Schulman wrote to Jean Pinkley—another MVNP archaeologist—asking for restraint: “As for further work on this Navajo Canyon tree, why don't we hold this whole matter for the time being? . . . Perhaps it will be possible for me to get up to Mesa Verde again . . . and the matter can be revived at that time” (Schulman to Pinkley, letter, 8 January 1958, MVNP Archives, WMAP RC-4-K4, Box 11, “Dendrochronology”). On January 16, 1958, LTRR secretary Helen Griffin handwrote a postscript on Schulman's unsent letter: “It is my painful duty to inform you that Dr. Schulman suffered a stroke and passed away a few hours after dictating the above letter.” Neither Schulman, Watson, nor Lancaster ever published an article on the matter, and the forest stand in question was informally named Schulman Grove in his honor.

In the early 1960s, Nichols and Smith reengaged the subject of possible stone-axe-cut tree limbs and human agency in the development of Schulman Grove under the auspices of the WMAP. In 1965, they published a remarkable article entitled “Evidence of Prehistoric Cultivation of Douglas-Fir Trees at Mesa Verde” (Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965), in which they asserted evidence that three trees at Schulman Grove—one living and two dead—had stone-axe-cut limbs preserved on them. They went further, however, arguing that the sequence of tree-ring dates from the two dead trees suggested that precolumbian loggers had manipulated the trees to produce beams of predictable size and shape (see below). In other words, Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) believed they had discovered evidence for precolumbian forest-management practices at Schulman Grove.

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. That evidence must be replicable and verifiable. If Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) are correct, Schulman Grove is unique in the U.S. Southwest. None of us, despite more than a century of combined dendroarchaeological experience and fieldwork, has ever found conclusive evidence of precolumbian stone-axe-cut tree stumps or limbs outside of archaeological contexts. Nor have our colleagues, including Chris Guiterman and his colleagues, who have spent decades identifying source forests and stands for the hundreds of thousands of trees that were demonstrably cut down in the Chuska and other mountain ranges for construction projects in Chaco Canyon in northwestern New Mexico (see Guiterman et al. Reference Guiterman, Baisan, English, Quade, Dean and Swetnam2020; Chris Guiterman, personal communication 2020). (From an archaeological perspective, none of us have ever seen a discarded or lost stone-axe head in those forests either. This is not surprising, however, given the high labor investment required in their manufacture and maintenance [see Adams Reference Adams2002].)

Given the extraordinary nature of Nichols and Smith's (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) claims, we decided to treat their conclusions as hypotheses to be tested rather than facts to be accepted. In doing so, we sought to answer two questions: (1) Is there replicable dendroarchaeological evidence for stone-axe-cut tree limbs on the trees in Schulman Grove? (2) If such evidence is available, is it then possible to infer, with any degree of confidence, that precolumbian loggers engaged in forest management practices there? Before addressing those questions, we need to review the challenges of anthropogenic ecology, discuss the morphology of stone-axe-cut beam ends, and engage in a short review of the history of tree-ring dating at MVNP to set the analytical stage.

Anthropogenic Ecology

In a cogent introduction to anthropogenic ecology, ethnobotanist Karen Adams outlined the challenges present when trying to infer ancient behavior on the modern landscape:

Assessing anthropogenic effects on ancient environments, however, can be quite complicated [for] landscapes are continually changing for natural reasons, such as climate shifts, short-term events, and evolution. The passage of centuries both mutes and blends the evidence of human and natural actions [Reference Adams and Minnis2004:167].

In assessing the developmental history of Schulman Grove, we need to differentiate, if possible, between natural and (potentially) cultural variables and processes. We do this through the analysis of two independent datasets: wood morphology and tree-ring dates.

Stone-Axe-Cut Beam Ends

Precolumbian loggers did not have access to metal tools. They used hafted stone axes to cut (pound) away the bark, cambium, and wood at the base of a living tree until the tree fell or could be pushed over. Hafted stone axes are effective at cutting living trees and green wood, but they are ineffective on dead trees and dry wood. If one hits dead wood with a stone axe, the axe will simply bounce back.

Because hafted stone axes are used to pummel wood away from the base of a tree bole, they produce distinctive morphological attributes on the harvested beam and the stump from which it was cut (Figure 2). A stone-axe-cut beam end is usually symmetrical in profile because it is easiest to girdle the tree by working around its entire circumference. Bent or torn wood may be present at the center of a stone-axe-cut beam end, indicating that the tree was pushed or pulled over to break it off at its base, or that it fell of its own accord. Individual growth rings may still be visible on ancient stone-axe-cut beam ends because of intra-ring differences in wood density.

Figure 2. An ancient, stone-axe-cut beam end. Note the v-shaped, roughly symmetrical profile of the cut. Tree-ring dating indicates that it was cut down in AD 625. (Photograph by Rick Wicker. LTRR Specimen No. MLK-264, image courtesy of Denver Museum of Nature & Science, DMNS Negative No. IV.CI-GP-322.d.)

Metal-Axe-Cut Beam Ends

A metal-axe-cut beam end has different but equally distinctive attributes, largely in the form of smoother surfaces. This is because the broader, sharper, and narrower metal blades cut wood in a way that stone axes do not (Figure 3). Metal axes slice wood fibers more cleanly than stone axes. The arc swung by a metal axe can also create a more acute cutting angle relative to the bole than that of stone axes. Metal-axe-cut beam ends tend to be less symmetrical than stone-axe-cut beam ends because loggers can, if they so choose, chop through the entire bole from one side.

Figure 3. Historic metal-axe-cut beam end. Note the smooth surfaces and asymmetrical profile. (Uncatalogued teaching specimen at LTRR. Photograph by Rick Wicker. DMNS Negative No. IV.CI-7.c.)

Ancient stone-axe-cut beam ends are abundantly preserved in cliff dwellings at MVNP because the sites have been protected in dry rockshelter environments from destructive forces, including fire, water, wind, and various chemical and biological agents (Schiffer Reference Schiffer2002). Stone-axe-cut beam ends are not well preserved in open-air pithouse sites, however, because burial has led to rapid wood decay, and pithouses are often burned when abandoned.

Given that that precolumbian loggers cut tens of thousands of construction beams from forests around MVNP, there must have been—at one time in the ancient past—tens of thousands of stone-axe-cut tree stumps, stubs, and limbs present in those forests. Unfortunately, the vagaries of time have worked their destructive power over the eons. Aside from Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965), archaeologists have never claimed to have documented a precolumbian stone-axe-cut stump anywhere in the American Southwest.

Tree-Ring Dating at Mesa Verde National Park

In addition to picturesque and famous cliff dwellings, MVNP has more than 4,500 documented archaeological sites and features, including thousands of pithouses, field houses, and irrigation and water control features, among others. Thousands more remain undocumented given that archaeologists have systematically surveyed only half of MVNP's area.

Schulman, who was not an archaeologist, first collected tree-ring samples from living trees at MVNP in 1941, during a search for old-growth trees to help him push the southwestern tree-ring master chronology further back in time (Douglass Reference Douglass, Andrew E.1942). In 1945, he collected cores from living trees in other canyons, including Navajo Canyon, but appears to have missed the old-growth stand that now bears his name (Schulman Reference Schulman1946).

In 1951, Terah Smiley (Reference Smiley1951) published a compendium of all archaeological tree-ring dates then available from the U.S. Southwest, including 136 dates from 26 sites at MVNP. Smiley's database does not constitute an overwhelming body of tree-ring-dating evidence for MVNP, especially given the total number of archaeological sites within its boundaries.

With increased post–World War II visitation straining National Park Service (NPS) facilities and posing a greater threat to MVNP's archaeological resources, NPS initiated the Wetherill Mesa Archaeological Project (WMAP) in 1958. WMAP fieldwork continued through 1963 and included a systematic archaeological and biological research program to mitigate the impact of infrastructure development on Wetherill Mesa (Fritts et al. Reference Fritts, Smith, Stokes and Osborne1965; Nichols Reference Nichols1963; Nichols and Harlan Reference Nichols and Harlan1967; Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965).

Because of WMAP's emphasis on dendrochronology, the project obtained large numbers of new tree-ring dates from secure archaeological contexts. In so doing, WMAP increased the analytical and interpretive potential of tree-ring dates from MVNP beyond the strictly chronometric and toward behavioral (e.g., wood use) variables (see Dean Reference Dean, Dean, Meko and Swetnam1996a, Reference Dean, Dean, Meko and Swetnam1996b).

During the 1960s and 1970s, LTRR conducted the “Synthesis Project,” a massive, long-term National Science Foundation–funded effort to make sure that all tree-ring dates produced over the previous half century had been (re)examined and (re)confirmed. Robinson and Harrill (Reference Robinson and Harrill1974) published the Synthesis Project's confirmed tree-ring dates for MVNP but did not include dates derived by WMAP, nor those derived by Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) for Schulman Grove. Because those efforts occurred concurrently with the Synthesis Project, they were not under its purview. As a result, systematic reanalysis of the Schulman Grove specimens did not occur for nearly five decades, until we engaged this project (see below).

In the 1990s, dendroarchaeologists conducted intensive sampling and dating projects at Balcony House (Fairchild-Parks and Dean Reference Fairchild-Parks and Dean1999), Long House (Street Reference Street2001a, Reference Street2001b), Oak Tree House (Windes Reference Windes1995), Spring House and 20-1/2 House (Parks and Dean Reference Parks and Dean1997), and Square Tower House (Dean Reference Dean2018). These efforts, which often included a 100% sampling strategy, produced large numbers of new dates and ensured that the vast majority of datable wood specimens from cliff dwellings at MVNP were dated, if possible.

In 2007, in response to the destruction wrought by the Bircher (2000), Pony (2000), and Long Mesa (2002) fires—which burned nearly 50% of MVNP—Nash began working with park archaeologist Kara Naber to tabulate and synthesize all the known archaeological tree-ring dates from within the park. Naber had also taken a special interest in the trees of Schulman Grove, and in 2005, she convinced NPS officials to assign it an archaeological site number (5MV4814), thereby tacitly endorsing Nichols and Smith's (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) assertion that the grove contains anthropogenic features. In 2006, she collected cross-sections from dead trees in Schulman Grove. In 2007, she returned with Nash to examine the grove and collect additional samples.

Given the century-long history of MVNP tree-ring dating, Nash had three goals at the onset of his project. He sought to ensure the following:

(1) That all potentially datable wood beams from all cliff sites at MVNP were sampled and, if possible, dated by dendrochronologists at LTRR

(2) That all of the more than 400 previously collected but undated tree-ring samples in MVNP collections were examined and, if possible, dated

(3) That all archaeological tree-ring dates from MVNP were available in a single database that included subsite provenience and collector information for all dates and samples

We now have a database of 4,392 tree-ring dates from 143 MVNP sites. That database provides us with a good understanding of when precolumbian tree cutting—and by extension, site construction—happened at MVNP, particularly during the thirteenth century, when sample sizes are largest (Nash Reference Nash, Nash and Baxter2021; Nash and Rogers Reference Nash, Rogers, Parezo and Janetski2014).

The Schulman Grove

The Schulman Grove is a small stand of old-growth Douglas-fir trees growing on a rocky, steep, north- and west-facing slope in Navajo Canyon on the west side of Chapin Mesa. Given those characteristics, it meets the criteria Douglass (Reference Douglass, Andrew E.1939) and Schulman (Reference Schulman1954) set forth for finding sites that contain climatically stressed trees that can grow to extraordinary ages. Such sites include rocky, well-drained substrates, north- and west-facing slopes, and locations within semiarid places—such as MVNP—with distinctly seasonal rainfall patterns.

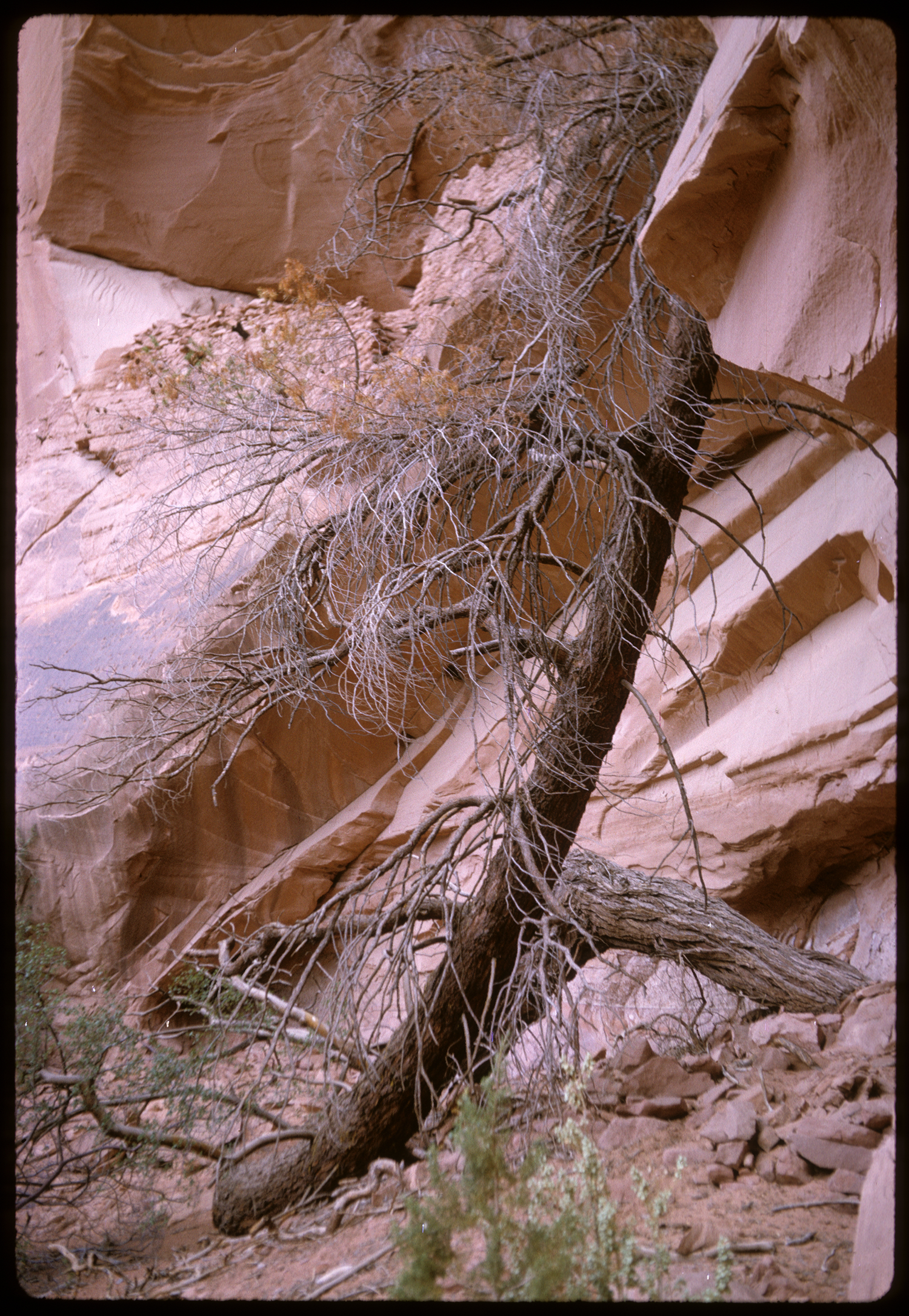

Dendrochronologically sensitive sites such as Schulman Grove often produce long-lived trees growing in strange forms. Trees get damaged when rocks fall from the cliff face above them as well as during large snowfall events. As a result, branches and stems bend and break. Some of those injuries result in tree death, whereas others do not. Some trees can survive with injuries that take years, decades, and even centuries to overcome. Dean encountered such a tree in front of NA 2543—a Pueblo II period cliff house in upper Tsegi Canyon, northeastern Arizona—in 1964 (Figure 4). Schulman Grove contains at least three such trees, to which we will turn in sequence.

Figure 4. A uniquely bent Douglas-fir in Tsegi Canyon, northeastern Arizona. The bole grows horizontally out from the cliff face, turns down and to the viewer's left, loops along the ground, and then turns back up, toward the viewer. In all likelihood, a falling rock or massive snowfall event bent and injured the tree when it was young. (Photograph by Jeffrey S. Dean.)

MVR-2500 (a.k.a. Schulman Old Tree – 1)

In 1946, Lancaster collected a tree-ring core from a tree in Navajo Canyon that he thought “exceptionally old” (Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:57). Lancaster sent the core to Schulman at LTRR, and Schulman visited MVNP in 1947 to inspect the tree himself. In keeping with LTRR protocols, Schulman designated the tree “MVR-2500” before collecting 21 increment cores from it. Back in the lab, he determined that the tree was at least 800 years old, making it the oldest known living tree within MVNP. He estimated that it started growing about AD 1150, although the earliest dated ring he had was from AD 1176 (Schulman Reference Schulman1947:8). Given these dates, MVR-2500 would have already been more than a century old when Ancestral Puebloans left MVNP during the last quarter of the thirteenth century. MVR-2500 remains the oldest living, documented Douglas-fir in the park. Beyond its remarkable age, MVR-2500 is fascinating because it has grown horizontally, or nearly so, for most of its long life (Figure 5).

Figure 5. MVR-2500, a.k.a. the Schulman Old Tree – 1, in Navajo Canyon, MVNP, around 1954 (left) and in 2007 (right). Three primary stem sections are visible in each photograph. The first section, between Rick Ahlstrom on the left and Nash on the right, grows horizontally out of the cliff face at a 30°–40° angle to that face. The second, proceeding back (west) from Nash's right, is roughly horizontal and runs parallel to the east-west trending cliff face. The third, visible in the background, runs southwest and slightly up along the cliff face, roughly 50° off vertical, hugging the cliff as it goes around the corner, up and out of view at the top left of the photographs. The white circle on the 1954 photograph (left) surrounds the purported stone-axe-cut stump (sample number SOT-1-L), collected by Nichols and Smith in 1963. Normal growth obliterated or covered all evidence of SOT-1-L by 2007 (cf. Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:Figure 4). (Left photograph on file at LTRR and courtesy of the Arizona Board of Regents. Right photograph courtesy of John Whitaker. Composite image created by Erin Baxter.)

We have no reason to challenge Schulman's dendrochronological analysis or his reconstruction and description of MVR-2500's life story, so we quote it at length:

The distorted form of this fir . . . seems to be the result of two major events in its career. After a slow start under suppression and assuming in its first century the common [vertical] L-shaped form of Douglas-firs growing on steep slopes, this tree, sometime near A.D. 1250, was apparently bent some 30°–40° to one side, perhaps by the fall of a rock or nearby tree or by the displacement of a supporting rock. Following this came an interval of undisturbed growth, lasting at least 300 years, which gave the tree a straight vertical stem above the 10-foot level. A second violent change in axis occurred after the tree had reached the over-age, snag-top stage; again, the entire stem was bent, at an angle of almost exactly 45°, apparently as a result of the decay and movement of the sandstone block . . . which acts as its buttress [Schulman Reference Schulman1947:2; emphasis added].

Schulman noted in 1947 that MVR-2500 was still growing vigorously, with many active branches and green cones near its top. That was still the case when Nash last visited it in 2009. It is noteworthy that Schulman never mentions the presence of stone-axe-cut stumps on this tree or the possibility of human agency, in the form of precolumbian forest management, as a causal mechanism for its peculiar growth. For Schulman, in 1947, MV-2500 was an exceedingly old Douglas-fir. Nothing more, nothing less.

As noted at the beginning of this article, on November 19, 1954, Watson wrote Schulman to call his attention to an enormous, dead, triple-trunked Douglas-fir from Schulman Grove that “has the stubs of three branches which were cut off with stone axes” (Watson to Schulman, letter, 19 November 1954, MVNP archives WMAP RC-4-K4, Box 11, “Dendrochronology”; emphasis added). To be clear, Watson was not describing MVR-2500; he was telling Schulman about another tree (later designated Lancaster Old Tree – 1; see below).

Watson's letter, written by an archaeologist to a dendrochronologist, marks the first time that anyone asserts the presence of stone-axe-cut stumps at Schulman Grove. It is disappointing that Watson did not lay out the criteria by which he—or more precisely, Lancaster—made the original assessment of stone-axe-cut limbs in the field. He merely asserted that they were present. In fairness, both Watson and Lancaster were seasoned archaeologists, and they would have been familiar with the morphology of well-preserved stone-axe-cut beam ends preserved in cliff dwellings (Figure 2). Nevertheless, Watson and Lancaster's failure to provide photographs or other documentation and criteria for the basis of their assertion is problematic.

Schulman's reaction to Watson's letter is important. It was enthusiastic, it accepted Watson and Lancaster's interpretation at face value, and it did not ask for supporting data. Schulman excitedly declared it to be a “jackpot site” and offered “congratulations to the keen-eyed [person] who found the triple-trunked tree carrying beam ends” (Schulman to Watson, letter, 23 November 1954, MVNP Archives, WMAP RC-4-K4, Box 11, “Dendrochronology”; emphasis added). Without examining the tree in question, Schulman, the preeminent North American dendrochronologist, provided authoritative confirmation of a purported feature (the supposed stone-axe-cut beam end) resulting from an ancient behavioral event in the absence of chronometric or morphological data, much less rigorous dendrochronological analysis or hypothesis testing. Then, Schulman did something astonishing. He revised his original interpretation of MVR-2500's life history, this time invoking human agency:

The history of [LOT-1; see below] caused me to review that of the 800-year Douglas-fir [MVR-2500; see above]. In considering the reasons for the remarkable shape of that tree [Schulman Reference Schulman1947:2], it seemed a bit on the romantic side to suggest that the first alteration job was [of] human origin, and the change near A.D. 1250 was ascribed to something such as a slide or fall damage. But it looks now as if that tree, too, were cut by Indians when it was young, and the original stump is buried within the present stem [Schulman to Watson, letter, 23 November 1954, MVNP Archives, WMAP RC-4-K4, Box 11, “Dendrochronology”; emphasis added].

Schulman had no evidence, beyond Watson's assertions about a different tree, that MVR-2500 was “cut by Indians when it was young,” nor did he have any evidence that “the original stump is buried within the present stem.” Not being an archaeologist, Schulman deferred, perhaps understandably, to Lancaster and Watson's expertise, but he is now guilty of proof by assertion and affirmation of the consequent, both of which are logical fallacies—that is, Schulman made an argument based on missing evidence (the supposedly buried stone-axe-cut stump) that he postulated but could not see. For a data-driven empiricist, this is extraordinary. Perhaps he was a “romantic” after all. That said, we should be clear that Schulman made these interpretations in private correspondence with colleagues, not in published venues. We do not know what, if anything, he would have published on the matter had he not died prematurely in 1958.

The Wetherill Mesa Archaeological Project

In late summer 1963, Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:57) went to Schulman Grove to resample MVR-2500, which they renamed “Schulman Old Tree – 1” (SOT-1) to honor the pioneering but recently deceased dendrochronologist. They collected 13 cores, 9 of which extend back into the thirteenth century, confirming Schulman's initial age assessment. Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) were interested in studying the potential behavioral implications to which Schulman alluded a decade earlier. As such, they collected two dead limbs emanating from SOT-1, designating these samples SOT-1-L and SOT-1-M (Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:58–60).

In their words, SOT-1-L “was sectioned because it appeared to have been cut with a stone ax” (Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:59; emphasis added). This marks the first time that archaeologists asserted, in a peer-reviewed publication, the possibility of stone-axe-cut limbs being present on SOT-1.

In addition to being an archaeologist, Nichols was a practicing dendrochronologist who had been working at LTRR for several years. Consequently, he and Smith knew a lot about MVNP archaeology and tree-ring dating. Although we cannot prove it, Nichols and Smith must also have been aware of Watson and Schulman's prior correspondence regarding possible anthropogenic activity at Schulman Grove. (Indeed, if Nichols and Smith had not been aware of that prior discussion, it begs the question of why they went to Schulman Grove at all—it was not recorded as an archaeological site at the time. But it was, apparently, recorded in LTRR's and MVNP's scholarly oral histories.) Nichols and Smith's (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) dendrochronological conclusions with respect to SOT-1-L are therefore worth quoting verbatim:

[SOT-1-L's] pith date is A.D. 1207 and its outside ring is A.D. 1289. Close examination of the weathered end of SOT-1-L shows that the limb was probably broken rather than cut with an ax. The 1289 outside date, however, follows only by nine years the latest archaeological [tree-ring] date recorded from Mesa Verde, possibly indicating that the limb was purposely broken by man [Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:59, 63; emphasis added].

We have no reason to question their dendrochronological results (yet—see below), but we do question their behavioral interpretations. Their first statement, based on morphology alone, is less than conclusive with respect to anthropogenic origins—the limb “was probably broken rather than cut with an ax.” Nevertheless, they conditionally inject human agency into their next sentence: “. . . possibly indicating that the limb was purposely broken by man.” Curiously, Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:59) thought the nine-year gap between their last known archaeological tree-ring date from MVNP—1280—and their 1289 outer date for SOT-1-L made it more likely that SOT-1-L was anthropogenic. We disagree (see below). Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) failed to describe the exterior of the limb and did not use LTRR's (then recently) developed symbols for describing terminal rings and differentiating between cutting and noncutting dates (see Nash Reference Nash1999:17).

A cutting date records a tree's date of death. A noncutting date, by definition, must be earlier (older) than a cutting date. Dendrochronologists now apply a “vv” symbol to modify a tree-ring date so as to indicate that an unknown—and possibly large—number of rings is missing from the outside of the specimen. A noncutting date underestimates the tree's actual death date.

Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) published a simple calendar-year date for the last datable ring they saw on SOT-1-L. Consequently, we cannot determine if their 1289 date is a cutting, near-cutting, or noncutting date (see Towner Reference Towner2002). If it is a noncutting date, there may be many rings missing from the sample exterior, making it even less likely to be related to the precolumbian occupation of MVNP.

The latest tree-ring date in our MVNP database, out of a suite of 4,392 dates, is 1281 from a loose log (specimen no. SPR-563) at Kiva D in Spruce Tree House. We believe the eight-year gap between the latest archaeological tree-ring date in MVNP and the 1289 date from SOT-1-L provides circumstantial evidence that SOT-1 does not contain evidence of stone-axe cuts made by humans. There are thousands of thirteenth-century tree-ring dates from MVNP, when cliff dwellings were still being built and occupied (Nash Reference Nash, Nash and Baxter2021; Nash and Rogers Reference Nash, Rogers, Parezo and Janetski2014). We have a good record of when people were living there, cutting wood, and building cliff dwellings. To belabor the point, it is unlikely that the only stone-axe-cut stump present and documented on the landscape within MVNP boundaries would postdate the latest known archaeological tree-ring date—from a suite of thousands of dates—by eight years. By chance alone, we would expect a tree-ring-dated stone-axe-cut stub, stump, or limb to date within the bulk of the known MVNP date distribution, which is when construction activity was at its peak, rather than occur as an outlier in a well-documented distribution of 4,392 dates. There is no reason to believe that Nichols and Smith's (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) 1289 date for SOT-1-L is anything but a noncutting date assigned to a single annual ring grown on one branch of an unusual tree. Occam's razor suggests that SOT-1-L is not anthropogenic.

Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) sampled a second dead limb on SOT-1, designated SOT-1-M, which “points to the west . . . at a point 7 ft. from the base of the tree” (Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:60; see their Figure 4). Their dendrochronological conclusions on SOT-1-M are worth quoting in full:

The pith . . . was dated A.D. 1266. The limb continued growing about 300 years, although the tree-ring series became increasingly erratic in the fourteenth century. This erratic growth may have been due to a shift in terminal dominance when another portion of the tree became the terminal stem, thus sapping more and more strength from SOT-1-M until it died. It is very likely that SOT-1-M was actually the original main stem of the tree and had been bent horizontally while still young [Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:59].

This is a dendrochronologically defensible statement that does not extend into speculation. Human agency is not invoked given that natural forces and processes can easily account for the attributes exhibited by SOT-1-M.

Unfortunately, by the late 2000s, five decades of healthy growth on SOT-1 obliterated all evidence of the locations at which Nichols and Smith collected SOT-1-L (Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:60; see Figure 5 above). Making matters worse, and despite extensive searching in both the MVNP and LTRR collections and archives, we could not find either specimen (SOT-1-L or SOT-1-M), so we cannot confirm the dates offered by Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965).

Another specimen, SOT-1-A, collected at an unknown location on the tree, was discovered in MVNP collections. Towner analyzed it in 2009, and it yielded a noncutting date of 1294vv. It is possible that SOT-1-L and SOT-1-A are the same specimen. Their pith dates (1207) are the same but their outer dates differ by five years (1289 for SOT-1-L and 1294vv for SOT-1-A). It is possible that Towner's reanalysis of the same specimen, using modern chronologies and with better surface preparation, yielded the actual date, which would imply that Nichols and Smith's (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) date was in error. It is also possible that SOT-1-A and SOT-1-L are different samples. Whatever the case may be, Towner's noncutting 1294vv date for SOT-1-A postdates the last known archaeological tree-ring date at MVNP by 13 years. Using the logic presented above, it is therefore even less likely to document human agency than Nichols and Smith's 1289 date.

None of the dendrochronological evidence we have suggests anthropogenic modification of SOT-1. Natural forces can account for the tree's unique attributes and life history, which Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) acknowledge. The only thirteenth-century date for SOT-1 published by Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) cannot be confirmed because their dated sample (SOT-1-L) is missing. The only thirteenth-century date we have is for specimen SOT-1-A, which may or may not be SOT-1-L. Even if they are the same specimen, both tree-ring dates postdate the last known archaeological tree-ring date from MVNP by at least 8–13 years, and probably more, given that the 1294vv date Towner derived for SOT-1-A is a noncutting date. As a result, all we can definitively say at this point is that the Shulman Old Tree – 1 (a.k.a. MVR-2500) is the only documented, currently living tree that was alive when Ancestral Puebloans were living at MVNP.

The Lancaster Old Tree – 1 (LOT-1)

In his November 19, 1954, letter to Schulman (quoted above), Watson described the amazing tree (LOT-1) Lancaster had discovered earlier that year. LOT-1 is located about 100 ft. (30 m)west-southwest of SOT-1, but it is around the cliff face toward Navajo Canyon and apparently escaped Lancaster's notice in 1946 and Schulman's in 1947. As Watson noted, the tree was triple trunked and spiral grained, indicating great age, and supposedly had stone-axe-cut limbs sticking out of its base (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Lancaster examining Lancaster Old Tree – 1 (LOT-1) in 1954 (left). Nash (left) and Naber (right) examining remnants of the tree in 2007 (right). The photographer in 1954 stood to the right of where Naber sat in 2007 and looked approximately north. The photographer in 2007 is facing approximately east. LOT-1 consists of three large, spiral-grained trunks. Lancaster's right hand rests on LOT-1-N. LOT-1-W is to the left. LOT-1-S is in the foreground. The only remaining trunk in 2007 is LOT-1-S. Note the long, highly unusual branch growing directly in front of Lancaster, which he cut and documented as LOT-1-B. It is now affectionately referred to as “Stumpie” (see Figure 8). (Left photograph on file at LTRR and courtesy of the Arizona Board of Regents. Right photograph by John Whitaker and used with permission.)

Watson described the tree, and his interpretation of it, to Schulman in great detail:

[LOT-1] is about 40 inches in diameter at the base. About 1 foot off the ground this huge trunk separates into three branches, the largest at least 18 inches in diameter. Growing out of the base of one of these branches is a small branch about six inches in diameter. . . . It has the stubs of three branches which were cut off with stone axes. . . . We don't think there is any doubt about the cuts having been made by stone axes. They are completely typical of it, exactly like the ends of beams in the ruins [Watson to Schulman, letter, 19 November 1954, MVNP Archives, Wetherill Mesa Archaeological Project RC-4-K4, Box 11, “Dendrochronology”; emphasis added].

Based on his analysis of the two cross-sections, a core, and five photographs Watson had sent, Schulman proffered his explanation of LOT-1's life history:

The Indians cut down a fairly young tree (about A.D. 1225 +/- 25?) with sufficient low branchlets left so that it recovered and several of these branchlets, or more probably some new ones, took over as vertically growing leaders. A couple of decades later, the Indians cut these new leaders off—nice straight poles—and again enough low branches were left so that the tree remained alive. Three new branches were put out which took over again as leaders and these are the three trunks of today [Schulman to Watson, letter, 23 November 1954, MVNP Archives, WMAP RC-4-K4, Box 11, “Dendrochronology”; emphasis added].

To reiterate our challenge: Lancaster and Watson claimed they had found precolumbian stone-axe-cut stumps based solely on tree morphology. Schulman built on their assertion and, using a small number of tree-ring dates, wrote a narrative describing LOT-1's supposed anthropogenic origins. A decade later, Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) built on Schulman's interpretation with their own research and a small number of new dates. Their published account of LOT-1 is therefore worth quoting in detail (Figure 7):

The pith dates from LOT-1-B, C, and W, which are from samples taken [from the three main stems] about 2 ft. above the ground, are between A.D. 1205 and 1211. Assuming that it would take a Douglas-fir seedling about five years to grow 2 ft., this tree probably began its growth late in the 12th century.

LOT-1-A is a spiraled limb about 6′ long protruding west from the south trunk about 2′ off the ground. The core from LOT-1-A was taken about 3′ from stone-ax-cut stubs, LOT-1-B and LOT-1-C, and has a pith date 20 years later than those limbs [e.g., ca. 1225–1231], indicating that LOT-1-A may be the original main stem of the tree. Apparently this main stem was bent west by natural forces or human intervention in A.D. 1217. This bending is indicated by the presence of compression wood in A.D. 1218 in branches LOT-1-C and LOT-1-W.

LOT-1-B, which apparently became the dominant terminal stem after the tree was bent [in 1217], was cut with a stone ax in A.D. 1233. This cutting stimulated a slight increase in ring width of LOT-1-W and a great increase in ring width for LOT-1-C in A.D. 1234.

LOT-1-C, a lateral branch next to LOT-1-B, apparently assumed terminal dominance in A.D. 1234. The limb grew rapidly for 13 years until A.D. 1247, when it was cut with a stone ax.

The cutting of LOT-1-C in 1247 is indicated by a great increase in ring width in LOT-1-W the following year (e.g. in 1248). LOT-1-W and two other laterals (LOT-1-N and [LOT-1- S] probably assumed equal dominance in A.D. 1248 and continue growing into the 20th century [Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:59–61; emphasis added].

Figure 7. Schematic diagram of the life history of LOT-1. (Redrawn figure based on Nichols and Smith [Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:Figure 7] and used with permission of the Society for American Archaeology. Redrawn by Erin Baxter.)

It is an amazing story worth retelling in simpler prose: A Douglas-fir, roughly 20 years old, grows in an isolated grove on a steep west-facing slope. A precolumbian logger, or perhaps natural forces, bent the tree in 1217. That bending induced the tree to create a new, vertically growing stem leader (LOT-1-B). Sixteen years later, in 1233, humans cut that leader (LOT-1-B). That cutting event induced the tree to create another new, vertically growing leader (LOT-1-C). In 1247, humans cut that leader (LOT-1-C), which was eventually replaced by the three new stem leaders (LOT-1-W, LOT-1-S, and LOT-1-N) that were still present on the tree when Lancaster discovered it in 1954.

There are several problems with this story. First, Schulman Grove is a sensitive—and therefore climatically stressed—dendrochronological site. Tree growth is closely tied to highly variable precipitation. One cannot simply assume that a sapling will grow two feet in five years. Equally problematic is that Nichols and Smith—like Schulman, Watson, and Lancaster before them—engage in the logical fallacies of proof by assertion and affirmation of the consequent. In other words, they assert the very human activities they are attempting to prove.

To give these reputable scholars the benefit of the doubt, it is possible that Nichols and Smith's (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) interpretations are correct. We agree that LOT-1 provides the most compelling case for anthropogenic intervention. It contains at least two stumps that look like stone-axe-cut stumps in both size and shape (Figure 8 and discussion below). The issue is whether we can offer conclusive proof that human agency affected the life history of this tree. The dates Nichols and Smith offer for the purported tree bending (AD 1217) and leader cutting (AD 1233 and 1247) are well within the period of major construction activity and occupation at MVNP (Nash Reference Nash, Nash and Baxter2021; Nash and Rogers Reference Nash, Rogers, Parezo and Janetski2014). It would therefore help if we could replicate and confirm their dating of LOT-1 samples, to which we now turn.

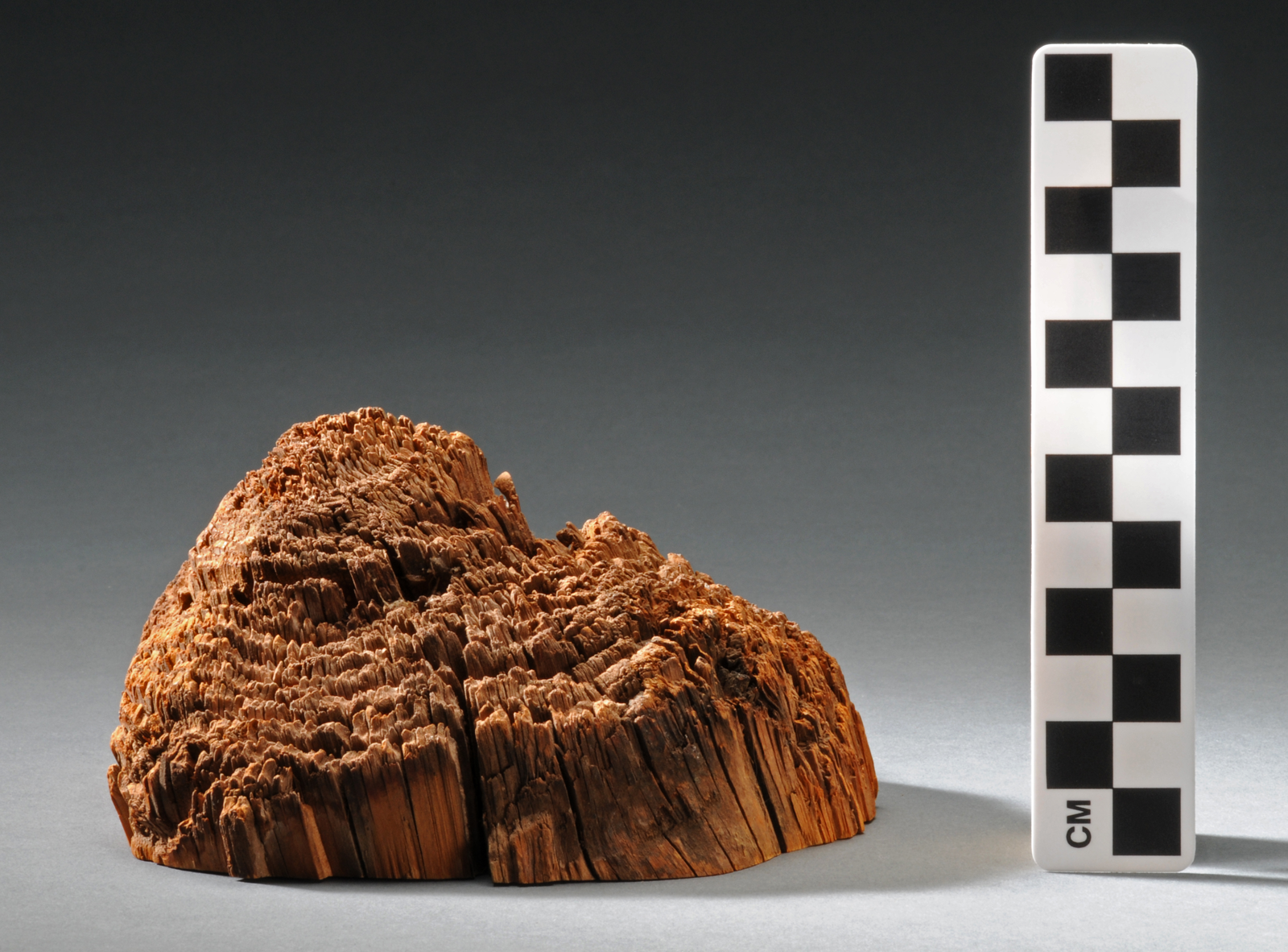

Figure 8. Watson cut this branch off of LOT-1 in 1954. Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) assigned it sample designation LOT-1-B (a.k.a. “Stumpie”; Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:62). Arrows point to limbs that appeared to have been cut with stone axes, the most morphologically convincing of which is at the upper center of the photograph, where the arrow points down. (Photograph on file at LTRR and courtesy of the Arizona Board of Regents.)

In 1954, Lancaster cut a large and peculiar branch off LOT-1. It is now specimen LOT-1-B and affectionately referred to as “Stumpie” (Figure 8). Towner analyzed Stumpie in 2010 and was unable to replicate Nichols and Smith's (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) dates using modern techniques, reference chronologies, and standards. We therefore cannot confirm their assertion that LOT-1-B was cut in AD 1233.

Modern dendrochronological dating criteria usually require at least 50–75 years of sensitive ring growth on a specimen before a reliable tree-ring date can be assigned. In some cases, dendrochronologists may be willing to provide a date when as few as 25 highly sensitive growth rings are present on the specimen, if the regional master tree-ring chronology is well established or if the sample is being dated with and against other samples collected from the same tree. Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) provide dates for samples with as few as 16 and 14 rings (LOT-1-B and LOT-1-C, respectively), something modern dendrochronologists would not do. Making matters worse, and despite extensive searching at MVNP and LTRR, their cores from Stumpie are missing and presumed lost. Dendrochronologically, we cannot confirm the LOT-1 dates published by Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965), nor—by extension—can we accept their interpretation of its history. All we can say is that Stumpie contains several curious stumps that look, morphologically, as if they may have been cut with hafted stone axes. But we cannot prove that assertion. Sadly, LOT-1 is no longer standing. It fell between 2007 and 2009.

The Lancaster Old Tree – 2 (LOT-2)

Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:61–63) stated that Schulman Grove contained the remains of a third, already fallen tree which had evidence of hafted stone-axe-cut limbs. They designated it “Lancaster Old Tree – 2” (LOT-2; Figure 9) and indicated that “Schulman examined a single section” of the tree in 1957 (Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:62)

Figure 9. Nash and remnants of Lancaster Old Tree – 2 in June 2007. (Photo by John Whitaker and used with permission.)

Nichols and Smith's (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) published interpretation of LOT-2 is worth quoting in detail:

About 30 ft. downslope from SOT-1 is a fallen Douglas-fir, LOT-2, with the stubs of limbs that were cut with stone axes. The remains of LOT-2 are lying east-west across the talus slope. All the stone-ax-cut stubs are west of the main trunk of the tree, indicating that this tree, when alive, was probably leaning toward the west. Possibly the tree was purposely bent by prehistoric occupants of the Mesa Verde.

In 1957, Schulman examined a single section from LOT-2-S, which consists of an inner limb that was enveloped by later growth of another limb. This inner limb was cut by a stone ax in A.D. 1275.

The core from LOT-2-A has an inside date near the pith of A.D. 1206 and an outside date of A.D. 1279. As in SOT-1, LOT-2-A shows a great increase in ring size beginning with A.D. 1233 and a slight increase at A.D. 1248. LOT-2-A was partially enveloped by later growth of the tree. This limb was probably cut by Indians, but because it was broken off in recent years no stone-ax-cut mark could be found.

LOT-2-B is two adjacent stone-ax-cut limbs, both being branches of the same stem (Fig. 11). The core taken from the single stem of LOT-2-B has an inside date near the pith of A.D. 1222 and an outside date of A.D. 1248. A sudden decrease of the tree-ring width of LOT-2-B in A.D. 1233 and a corresponding increase in ring size in LOT-2-A indicate that one of the two branches of the single stem may have been cut or mutilated in A.D. 1232. The other branch of the stem was cut in A.D. 1248.

LOT-2-C is a stone-ax-cut branch of LOT-2-S. LOT-2-C has an inside date of A.D. 1215, an increase in ring width in A.D. 1233, and an outside ring, covered by bark, which dates at A.D. 1235. The growth that enveloped LOT-2-S also enveloped LOT-2-C. This growth began to surround these limbs at about A.D. 1300 and continued for at least another 100 years [Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:61–62; emphasis added].

As before, Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) assert what they should be testing. A close examination of their published photographs of supposed stone-axe-cut stumps on LOT-2 (see Nichols and Smith Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:62–63, Figures 9, 10, and 11) look vaguely like the stone-axe-cut beam in Figure 2, but they are far smaller in diameter. We believe they look more like the old, weathered, worn ends of broken Douglas-fir branches that are naturally found all across the American Southwest and that are easy to find in MVNP.

Two samples from LOT-2 yielded dates coincident with the Ancestral Pueblo occupation of MVNP. The first, LOT-2-A, is a ½-inch core that they dated 1206–1279 and that we redated to 1205–1278vv. According to Dean's notes, LOT-2-A is from the “old part of [an] upper limb—does not go thru [sic] outer wood layer,” indicating that the tree ultimately grew over and around this broken limb (LTRR Schulman Grove Site [5MV4814] Files). The last dated ring on that specimen, 1278, falls within the known precolumbian archaeological tree-ring date distribution at MVNP, but it is a noncutting date, which means that the limb's date of death actually falls an unknown—and possibly large—number of years later. Consequently, that tree probably died after the last currently known archaeological tree-ring date of 1281 from MVNP. As such, the LOT-2-A date, in and of itself, does not provide us with conclusive evidence for anthropogenic manipulation of the tree, and the beam-end morphology, although interesting, is inconclusive as well.

The second dated LOT-2 sample is a core (specimen number 4005c) that Towner collected from an old branch buried in a cross-section that Naber collected in 2006. It yielded a noncutting date of 1249–1266vv. That noncutting date, by definition, underestimates the limb's death date by an unknown number of years. It is also important to note that this specimen contains only 17 rings—too few to be dated in isolation. Towner dated it, however, in conjunction with and against three other cross-sections from LOT-2, which allowed him to derive a more complete picture of that tree's growth history. Those three cross-sections yielded noncutting dates from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries (sample 4005a yielded a noncutting date of 1543++vv; sample 4005b yielded a noncutting date of 1408++vv; and sample 4007b yielded a noncutting date of 1485+vv). All three dates postdate the thirteenth-century Ancestral Puebloan occupation of MVNP in which we are interested, and they do so by at least 125 years. As such, Towner's 1266vv date for sample 4005c tells us that LOT-2 went through some life-changing events in the late thirteenth century, but it does not provide conclusive evidence of human agency.

Despite extensive searching, we could not find sample LOT-2-S, so we cannot confirm or refute the 1275 date published by Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965:Table 1).

Returning to the interpretation proffered by Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965), it may well be that LOT-2 experienced growth spurts and suppressions during the thirteenth century, but this happens frequently in nature, especially at such climatically stressed sites as Schulman Grove. It is circumstantially curious that Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) derived dates for LOT-1 and LOT-2 that are offset by only one year (1232/1233 and 1248/1249). Coincidence does not indicate causality, however, and it certainly does not indicate human agency. Indeed, if a major rock or snowfall event affected trees in Schulman Grove during those years, such coincidence is to be expected.

Given the totality of evidence from LOT-2, all we can say is that the tree had a good, long life stretching into the seventeenth century. The latest tree-ring date we have from LOT-2 is from specimen 4003, a noncutting date of 1651++vv. We cannot say that it displays conclusive evidence of hafted stone-axe cuts or forest-management activity in the thirteenth century.

Conclusion

In order to accept the hypothesis that human agency was recorded in the curious Douglas-firs at Schulman Grove, data from three independent lines of evidence—morphological, dendrochronological, and archaeological datasets—must complement and support each other. First, and with respect to morphology, the beams must look (a lot) like the well-documented stone-axe-cut beam ends from archaeological sites. Second, we must have reliable and replicable tree-ring dates for the stumps, limbs, and trees in question. Third, tree-ring dates on supposedly stone-axe-cut limbs must fall within the range of tree-ring dates we already have from secure archaeological contexts at MVNP.

To return to the first question posed in this article: Is there any reliable, confirmable, dendrochronological or archaeological evidence for stone-axe-cut tree stubs, stumps, or limbs in Schulman Grove at MVNP? The answer is unequivocally no.

Lancaster and Watson made an assertion, based on their experience as archaeologists, in a private letter to Schulman. Schulman built on their assertion with his dendrochronological experience. Their assertions existed in private correspondence and office discussion. None were subject to peer review before Schulman's untimely death in 1958.

In 1963, archaeologists Nichols and Smith joined the fray. The tantalizing prospect of human agency in the life history of trees at Schulman Grove was by then part of the research lore at both LTRR and MVNP. Nichols and Smith had no a priori reason to question the received wisdom from three respected archaeological and dendrochronological authorities (i.e., Lancaster, Watson, and Schulman). As such, Nichols and Smith's work at Schulman Grove appears designed to document and confirm an existing idea, not to test a plausible hypothesis rigorously.

With respect to SOT-1, the thirteenth-century date that Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) report for SOT-1-L and that we may have replicated with SOT-1-A postdates the last known MVNP tree-ring date by 8–13 years, and probably more. By chance alone, is it exceedingly unlikely that the only well-preserved and dated stone-axe-cut stump in the region would postdate the well-documented occupation of MVNP.

With respect to LOT-1, we could not redate “Stumpie” (LOT-1-B)—their most compelling piece of evidence. Stumpie is indeed peculiar. It contains several elements that morphologically appear similar to stone-axe-cut limbs, although the affected ends appear flatter than most (cf. Figures 2 and 8). In the absence of reliable, replicable tree-ring dates on Stumpie, we cannot responsibly proffer precolumbian human agency to account for the creation of those elements.

With respect to LOT-2, the thirteenth-century noncutting dates that Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) report for LOT-2 and the new dates that we derived for that tree (specimen nos. LOT-2-A, 4005c) compellingly land in the 1260s and 1270s, during the peak occupation of MVNP. In the absence of additional data, however, those dates merely demonstrate that LOT-2 was alive during the thirteenth century, and we know that the tree kept growing at least into the seventeenth century. Morphological evidence for stone-axe-cut beam ends on LOT-2 is less compelling, especially given that the tree had already fallen before Nichols and Smith examined it in the early 1960s.

Given the negative answer to our first question, the answer to our second question must also be negative: there is no reliable, replicable evidence for precolumbian, anthropogenic forest manipulation recorded in Schulman Grove.

It is easy to understand the exuberance that Lancaster, Watson, Schulman, Nichols, and Smith all felt at Schulman Grove. We shared their excitement, at least initially. Nichols and Smith (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) believed that they had dated stone-axe-cut stumps and found evidence of forest manipulation at Schulman Grove.

Many of Nichols and Smith's (Reference Nichols, Smith and Osborne1965) samples are now missing. Despite extensive searching at LTRR and MVNP, we cannot find them. The few dates we have been able to derive do not conclusively support their dating or arguments. Given that we have not been able to replicate their results, we cannot agree with their conclusions.

It is undeniable that precolumbian loggers harvested tens of thousands of trees from local forests to build the cliff dwellings in MVNP, with especially intense harvesting and construction activity occurring in the mid- to late 1200s. It is therefore undeniable that there were, at one time, tens of thousands of stone-axe-cut stumps present in the forests of MVNP and surrounding environs. Despite years of searching, archaeologists have never conclusively discovered and recorded precolumbian stone-axe-cut stumps or limbs on the landscape. The destructive forces of environmental decay over the course of more than seven centuries are simply too powerful for exposed wood to resist.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded, in part, by grants from History Colorado (No. 2008-02-030) to the Denver Museum of Nature & Science; from the National Science Foundation (No. BCS-0816400) to the Village Ecodynamics Project II at Washington State University in Pullman, Washington, and Crow Canyon Archaeological Center (CCAC) in Cortez, Colorado; and by a National Science Foundation grant (BCS-1923925) to the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona. Kara Naber set this project in motion with her passionate work on archives and collections. Comments by Karen Adams, Rex Adams, Richard Ahlstrom, Thomas Swetnam, and an anonymous reviewer greatly improved this article. John Whitaker, Rick Ahlstrom, Liz Francisco, and several others participated in fieldwork at Schulman Grove in 2007 and 2009. Gabriela Chavarria translated the abstract into Spanish.

Data Availability Statement

Archival documents cited in this article are on file at the LTRR and MVNP. All tree-ring dates cited and samples on which they are based are curated at LTRR or MVNP. Copies of Nash's database of archaeological tree-ring dates from MVNP are on file at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science.