Archaeologists are increasingly examining the widespread trade and commodification of fishes in the past. Much of this work focuses on historic periods and the trade of North Atlantic species, especially Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua), which were harvested in large numbers and underpinned food practices across Europe, supported colonial projects throughout the Atlantic World, and provided shelf-stable, staple foods that were eaten by numerous populations in several continents (e.g., Barrett and Orton Reference Barrett and Orton2016; Conrad et al. Reference Conrad, DeSilva, Bingham, Kemp, Gobalet, Bruner and Pastron2021; Faulkner Reference Faulkner1985). Owing to the importance of North Atlantic fisheries to the Atlantic World, considerable effort has been placed on tracing changing fishing methods and locations of, as well as human impacts to, these fisheries over time, especially via stable isotope and ancient DNA (aDNA) analyses (Amorosi et al. Reference Amorosi, McGovern and Perdikaris1994; Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Orton, Johnstone, Harland, Van Neer, Ervynck and Roberts2011; Edvardsson et al. Reference Edvardsson, Patterson, Bárðarson, Timsic and Ólafsdóttir2021; Fetner and Iwaszczuk Reference Fetner and Iwaszczuk2021; Ólafsdóttir Reference Ólafsdóttir, Pétursdóttir, Bárðarson and Edvardsson2017; Orton et al. Reference Orton, Makowiecki, de Roo, Johnstone, Harland, Jonsson and Heinrich2011). Although research on Atlantic Cod dominates this literature, studies of other North Atlantic species like Atlantic Herring (Clupea harengus) also contribute to these themes (Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Locker and Roberts2004; Enghoff Reference Enghoff2000; Makowiecki et al. Reference Makowiecki, Orton, Barrett, Barrett and Orton2016). In North American historic contexts, there has been a similar focus on long-term trends in the Atlantic Cod fisheries of the western North Atlantic (Betts et al. Reference Betts, Maschner, Clark, Moss and Cannon2011, Reference Betts, Noël, Tourigny, Burns, Pope and Cumbaa2014; Pope Reference Pope, Roy and Côté2004), and an increasing number of studies have examined the regional trade of fishes beginning in the mid-nineteenth century (e.g., deFrance and Kennedy Reference deFrance and Kennedy2019; Kennedy Reference Kennedy2017).

Although a rich body of research addresses precontact Indigenous fishing practices in western North America (e.g., Moss and Cannon Reference Moss and Cannon2011), the commodification and trade of fish in the Pacific World in the nineteenth century have been less well studied by archaeologists. Limited research focuses on nineteenth-century salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) and Pacific Cod (Gadus macrocephalus) fishing operations in western North America, such as Pacific coast salmon canneries (Betts et al. Reference Betts, Maschner, Clark, Moss and Cannon2011; Margaris et al. Reference Margaris, Rusk, Saltonstall and O'Dell2015; Newell Reference Newell1987; Ross Reference Ross2013). The nineteenth-century Chinese-operated fisheries that supplied Chinese diaspora communities dispersed across the Pacific World remain comparatively understudied. Analysis of fish assemblages from North American Chinese diaspora archaeological sites demonstrates the extensive regional trade of fishes collected by Chinese fishers throughout western North America, along with importation of a variety of Asian fish species (e.g., Collins Reference Collins1987; Kennedy Reference Kennedy2016, Reference Kennedy2017; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Heffner, Popper, Harrod, Crandall, Chang and Fishkin2019; Schulz Reference Schulz, Praetzellis and Praetzellis1997, Reference Schulz, Allen, Scott Baxter, Medin, Costello and Yu2002). Although this work documents the importance of Asian fishes in the food practices of Chinese diaspora populations, a general lack of comparative Asian fish skeletal specimens, the osteological similarities across commonly imported species, and unfamiliarity with the ecology of Asian fishes have often led zooarchaeologists to simply classify Asian fish species identified in North American contexts as “Asian imports” (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2017). This trend prevents in-depth analysis of the sourcing of fishes from specific locations in Asia like that seen in studies of North Atlantic fisheries, thus limiting understanding of trends in Chinese fishing strategies and the potential for comparative analyses of the commodification of fishes and their role in regional and transnational trade networks across both the Pacific and Atlantic Worlds. In a world increasingly affected by overfishing and climate change, understanding past fishing practices and fishers’ responses to changing fisheries across a variety of contexts, cultural systems, and fishing strategies is critical to addressing a wide range of conservation issues (e.g., Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Samhouri, Stoll, Levin and Watson2017; Perry et al. Reference Perry, Ommer, Barange, Jentoft, Neis and Sumaila2011).

In this study, we use aDNA to conduct genetic species identification of snakehead (Channa sp.) remains from the Market Street Chinatown, a nineteenth-century Chinese community in San Jose, California, to establish a starting point for addressing the widespread Chinese fishing practices that supplied Chinese diaspora communities throughout the Pacific World. We begin with a review of nineteenth-century Chinese migration and fishing practices, and we then discuss existing fish data from nineteenth-century Chinese diaspora communities, particularly the Market Street Chinatown. Next, we present the results of aDNA analysis of eight snakehead bones from the Market Street Chinatown and situate these results and the insights they provide in terms of nineteenth-century Chinese fishing practices. Ultimately, we suggest avenues for future analysis and comparisons with the well-established study of Atlantic World fisheries.

Chinese Migration and the Pacific World Fish Trade

In the last half of the nineteenth century, millions of Chinese people left southern China to seek opportunities throughout the Pacific World in myriad locations, including Malaysia, the Philippines, Australia, Peru, Canada, and the United States (Pan Reference Pan1999). These migrants were primarily young men from rural farming villages in China's southern Guangdong province who left because of a variety of push factors, including famine, floods, banditry, governmental collapse, and the effects of European colonial projects. Corresponding pull factors drew Chinese migrants abroad, including demands for cheap labor in a variety of contexts (e.g., agricultural labor and construction of the Transcontinental Railroad) and, in the United States, the promise of wealth sparked by the Gold Rush following the discovery of gold in California in 1848. Migration often followed family and clan lines, with new migrants drawing on the knowledge and resources of established migrants and migrant communities. Migrants typically maintained strong connections to their home villages and families in China, which often included wives and children who were supported by the wages earned by husbands overseas. In this context, migration became a valuable tool for increasing the financial resources, stability, and well-being of families struggling to survive (Hsu Reference Hsu2000). Chinese living abroad often worked in a variety of labor roles, including railroad construction, agriculture, laundries, and mining, as well as in Chinese-run extractive industries such as fishing, shrimping, and abalone harvesting (Takaki Reference Takaki1998). This mass migration drove demographic, architectural, and cultural shifts in southern China, and it created transnational connections between Chinese diaspora communities through the movement of people, correspondence, money, and things between migrant home villages and diaspora communities (Hsu Reference Hsu2000; Voss et al. Reference Voss, Ryan Kennedy, Tan and Ng2018). These flows created what historian Henry Yu (Reference Yu, Gabaccia and Hoerder2011, Reference Yu, Rose and Kennedy2020) calls the “Cantonese Pacific”: the multigenerational dispersed networks of southern Chinese people who helped shape the history of much of the Pacific World.

The Cantonese Pacific not only drove flows from China to migrant communities but also facilitated entrepreneurialism and created markets for goods produced at home and overseas for use throughout the diaspora. Critical to Chinese entrepreneurialism was the widespread exportation of the small shareholding business model as a technology of migration (Yu Reference Yu, Rose and Kennedy2020). Shareholding businesses consisted of small groups of shareholders who pooled their resources to better pursue business opportunities by splitting overhead and equipment costs and dividends based on the profits generated by the business. This model was employed wherever Chinese migrants settled in the Pacific World, and it offered a flexible way for a small number of investors, typically related along family or clan lines and often extending across multiple generations, to share risk and adapt their business practices to local social, economic, and environmental conditions (see Kennedy Reference Kennedy2015). The shareholding model was used in many businesses—from general stores to laundries to farming and fishing operations—and it became the standard unit of Chinese production abroad. Thus, whereas Chinese extractive industries like fishing operated on larger village-level scales, the production and trade of fish products were typically handled on the family or small business scale, regardless of whether Chinese fishers were operating in the United States, Australia, the Philippines, or elsewhere.

Small shareholding businesses needed effective ways to both move their products and send portions of their profits to shareholders’ home villages, because many Chinese living abroad played active roles in financially supporting families in their home villages and funding village and clan infrastructure upgrades like schools and roads (Tan Reference Tan2013; Voss et al. Reference Voss, Ryan Kennedy, Tan and Ng2018). The transport of goods, money, and people throughout the Chinese diaspora was facilitated by jinshanzhuang (“Gold Mountain Firms”), which were Hong Kong-based import/export firms that provided a range of services, including moving things and people to and from Hong Kong and the rest of the diaspora and acting as banks and funders of migration (Hsu Reference Hsu2000). These firms shaped the lives of Chinese abroad by sourcing and supplying the trappings of Chinese material life (e.g., ceramics, chopsticks, clothes) to urban and rural Chinese communities throughout the Pacific World (Hsu Reference Hsu2000; Voss et al. Reference Voss, Ryan Kennedy, Tan and Ng2018). Conversely, Chinese shareholding businesses and entrepreneurs abroad engaged in the production of export products—be it through fishing, ginseng harvesting, seaweed production, or other extractive industries—and they relied on jinshanzhuang to transport the bulk of their products to Hong Kong for sale. Jinshanzhuang and their agents thus acted as facilitators and intermediaries who moved goods produced overseas through their shipping networks for sale in urban Chinese markets and elsewhere in the diaspora (see Tsing Reference Tsing2015).

The products generated by Chinese diaspora communities depended on a confluence of local availability and politics, the suitability of resources to Chinese extractive or productive technologies, and demand in urban markets in southern China where many of these products were ultimately sold. Given the long-term trends in China of rising population and overharvesting of fish and wild animals, preserved food products—including luxury ingredients, such as bear paws and abalone, and staple foods like dried fish and shrimp—were increasingly in demand and particularly attractive to Chinese entrepreneurs overseas (Butcher Reference Butcher2004; Kennedy Reference Kennedy2017; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Rogers and Kaestle2018; Muscolino Reference Muscolino2009). In addition, southern Chinese foodways were flexible and incorporated dried fish products from many species (Simoons Reference Simoons1991), allowing dried fish production to become a critical source of income for many Chinese in coastal and riverine areas of the Pacific World.

Chinese fishers across the Pacific World typically organized into fishing communities centered on abundant fish supplies, with most Chinese fishing villages in North America forming on the Pacific coast or along large rivers like the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers (Armentrout-Ma Reference Armentrout-Ma1981; Collins Reference Collins1987; Lydon Reference Lydon1985). Fishers typically relied on imported Chinese fishing technologies like bag nets and junks (a type of near-shore vessel), and they prepared seafood products—including dried shrimp, squid, abalone, and finfish—using southern Chinese preservation techniques (Bentz and Schwemmer Reference Bentz, Schwemmer and Cassel2002; Braje et al. Reference Braje, Erlandson and Rick2007; Lydon Reference Lydon1985). The kinds of species caught depended on local availability, legal limitations, social pressures (e.g., threats of violence from American and European fishers focusing on salmon), and Chinese consumer demand for mild, white-fleshed fishes like drums (Sciaenidae) and flatfishes (Pleuronectiformes; Jordan and Gilbert Reference Jordan, Gilbert and Goode1884:735–736; Kennedy Reference Kennedy2017; Schulz Reference Schulz, Praetzellis and Praetzellis1997; Simoons Reference Simoons1991). However, the nature of Chinese fishing methods—especially the use of bag nets, gill nets, and seines—meant that Chinese fishers caught many species regardless of their primary target species.

Finally, one practice not commonly described in the United States but seen elsewhere in the Pacific World was the purchase of fresh fish from non-Chinese fishers for use in making dried fish. This practice has been documented in nineteenth-century fish-curing camps in Australia and throughout Southeast Asia (Bowen Reference Bowen2012; Butcher Reference Butcher2004), and it allowed Chinese merchants and shareholding businesses to supplement fish caught by Chinese fishers when production did not meet demand. Accounts of Chinese fishing operations in the Pacific World do not indicate how prevalent this practice was nor whether it was a standing business practice or a strategy employed to make up for unexpected shortfalls in Chinese fishers’ catches.

The Archaeology of Chinese Fishing in the Pacific World

Little direct archaeological data exist from Chinese fishing operations, because only a small number of nineteenth-century Chinese fishing camps have been investigated. Bowen's (Reference Bowen2012) excavations of a Chinese fishing and fish-curing village in Victoria, Australia, shed light on the lives of Chinese fishers in southeastern Australia. Fishers were connected to transnational trade networks that supplied material necessities including China-produced tablewares, medicines, and prepared foods and that gave them an outlet for their fish products. Although archaeological fieldwork at the site generated few fish remains, historical research indicates that Chinese fishers in Victoria caught and cured their own fish while also buying fish from local European-descended fishers to cure (Bowen Reference Bowen2012).

Williams's (Reference Williams2011) investigation of the Point Alones Chinese fishing village in Monterey Bay, California, likewise provides insights into the lives of Chinese fishers and their families. Ceramics recovered from Point Alones reveal clear connections to transnational trade networks; the presence of many of the same types of goods commonly found across Chinese diaspora sites spanning North America, Australia, New Zealand, and Guangdong Province reveals the shared material culture supplied by jinshanzhuang (see Voss et al. Reference Voss, Ryan Kennedy, Tan and Ng2018) and the strong ties that Chinese fishing villages had to jinshanzhuang-affiliated merchants. The Point Alones excavations produced copious amounts of fish remains, and preliminary analysis by Kennedy (unpublished observations) indicates that although Chinese fishers focused on harvesting large numbers of rockfishes (Sebastes spp.) and flatfishes, they also caught a diverse range of other locally available fishes like Pacific Hake (Merluccius productus), Cabezon (Scorpaenichthys marmoratus), and Wolf-eel (Anarrhichthys ocellatus). These data conform with historical accounts of Chinese fishing activity in Monterey Bay, and the species identified at the site generally align with nineteenth-century Chinese taste preferences (Jordan Reference Jordan and Goode1887; Simoons Reference Simoons1991).

Other Chinese fishing-related sites include shrimp-drying platforms in the San Francisco Bay Area (Schulz and Lortie Reference Schulz and Lortie1985) and abalone production centers in southern California's Channel Islands (Braje et al. Reference Braje, Erlandson and Rick2007). Shrimp-drying sites document the collection and drying of shrimp, one of the most important Chinese animal exports from North America (Bentz and Schwemmer Reference Bentz, Schwemmer and Cassel2002); however, given the fragility of shrimp shells and the lack of subsurface testing at shrimping sites, little remains of the products of these camps. More fieldwork has occurred in abalone harvesting sites in the Channel Islands, where archaeologists have documented the rise and collapse of Chinese abalone harvesting in the area. These sites highlight the variety of Chinese marine extractive industries in the Pacific World and the extent of jinshanzhuang-affiliated trade networks throughout western North America. Although not documented archaeologically, Chinese fishers established similar extractive industries and fishing villages across much of the Pacific World in the nineteenth century.

Given the low numbers of Chinese fishing camps investigated by archaeologists, evidence of nineteenth-century Chinese fishing practices has primarily come from fish remains recovered from other types of Chinese diaspora sites. The frequent recovery of large numbers of fish remains from Chinese sites in the American West documents the importance of fish in Chinese diaspora foodways and the extensive trade of fish products throughout the Pacific World (Collins Reference Collins1987; Kennedy Reference Kennedy2017; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Heffner, Popper, Harrod, Crandall, Chang and Fishkin2019; Schulz Reference Schulz, Praetzellis and Praetzellis1997, Reference Schulz, Allen, Scott Baxter, Medin, Costello and Yu2002). Chinese diaspora fish assemblages in North America typically contain many fishes, including North American marine and freshwater species and smaller numbers of Asian marine species. Identified fishes usually encompass a core group of taxa that include North American fishes like minnows (Leuciscidae), Sacramento Perch (Archoplites interruptus), rockfishes, flatfishes, and California Sheephead (Semicossyphus pulcher), alongside Asian fishes like Large Yellow Croaker (Larimichthys crocea), threadfin breams (Nemipterus spp.), and pufferfishes (Tetraodontidae). These fishes are found at all manner of Chinese diaspora sites in western North America—from large, urban communities (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2017; Schulz Reference Schulz, Praetzellis and Praetzellis1997, Reference Schulz, Allen, Scott Baxter, Medin, Costello and Yu2002) to rural labor quarters and railroad-related sites (Johnson Reference Johnson2017; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Heffner, Popper, Harrod, Crandall, Chang and Fishkin2019). Archaeological data from Chinese diaspora sites demonstrate the widespread trade of both Asian and North American fishes outside their native ranges.

The distribution of North American and Asian fishes to Chinese diaspora sites in the American West reflects the extent of Chinese fishing operations and the capabilities of jinshanzhuang-operated trade networks to redistribute fish from disparate fisheries throughout the Pacific World. Archaeological analyses have revealed patterns in the sourcing and trade of North American fishes among Chinese diaspora communities, such as the importance of disparate fisheries in southern California, San Francisco and Monterey Bays, and the San Joaquin and Sacramento River systems (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2017). However, it remains difficult to assess the trade of Asian fishes for a variety of reasons, including insufficient comparative specimens either to identify species of rare Asian taxa or to differentiate between closely related species imported from Asia. The inability of North American zooarchaeologists to determine the origins of species beyond “Asia” for imported Asian fishes has led to both implicit and explicit assumptions that fish species identified at Chinese diaspora sites in North America likely originated from the waters around Hong Kong (the primary export port supplying North America), including the South China Sea. These limitations have resulted in studies that typically either emphasize the bidirectional movement of goods between Hong Kong and places overseas or leave unexplored the specific origins of fishes at Chinese diaspora sites. Such assumptions obscure both historical evidence for the export of fish products to and from Chinese fishing communities in places like Australia and the Philippines and the scope and impact of the Chinese fish trade in the nineteenth century. Further, these assumptions limit the potential to bring studies of Chinese-operated fishing industries and trade into conversation with studies of large-scale fishing in other areas of the world, namely the North Atlantic.

The Market Street Chinatown

To address the lack of data relating to the trade and distribution of fishes from Asia by Chinese fishers, this study presents aDNA analysis of eight snakehead bones from the Market Street Chinatown. We provide a brief discussion of previous zooarchaeological findings from the site to better contextualize our results.

Market Street Chinatown was founded in 1866 in San Jose, California: it was home to 1,000 permanent residents and a “home base” to 1,000–3,000 Chinese laborers who returned between jobs and for holidays (Laffey Reference Laffey1993; Voss Reference Voss2008; Yu Reference Yu2001). Community members had access to many Chinese-run businesses, such as grocery stores, restaurants, butchers, and a fish market, and proximity to San Francisco's Chinatown ensured access to regional and international imports distributed by jinshanzhuang. Market Street Chinatown was more than a home to its residents: its outer walls provided protection against growing anti-Chinese sentiment and violence in the late nineteenth century. An anti-Chinese arson fire destroyed the Market Street Chinatown in 1887, and its residents relocated to two other Chinese communities in San Jose (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Scott Baxter, Medin, Costello and Yu2002; Yu Reference Yu2001).

Market Street Chinatown was excavated in the 1980s following Chinese-descendant community activism in opposition to an urban development project that threatened to destroy the site (Lum Reference Lum2007; Voss Reference Voss2008). Archaeologists conducted salvage excavations of more than 60 late nineteenth-century trash pits related to both tenement and mixed merchant-laborer contexts that contained a wide range of material culture and faunal remains (Voss Reference Voss2008). Although analysis of the Market Street Chinatown archaeological collection was not possible when the site was excavated, since 2002 it has been the focus of the collaborative Market Street Chinatown Archaeological Project (Lum Reference Lum2007; Voss Reference Voss2005), which has facilitated material culture and faunal analyses (e.g., Henry Reference Henry2012; Kennedy Reference Kennedy2016, Reference Kennedy2017; Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Rogers and Kaestle2018). The Market Street Chinatown faunal assemblage includes copious pork, beef, poultry, and fish remains alongside lower numbers of wild animal remains from North America including bear paws.

Kennedy's (Reference Kennedy2017) analysis of 5,759 fish remains from the site provides important historical context. The Market Street Chinatown fish assemblage is notable for the variety of species present. Based on the known ranges of identified species and documentary evidence of Chinese fishing operations in California, fish at the site can minimally be linked to southern California, San Francisco and Monterey Bays, the San Joaquin and Sacramento Rivers, and marine and freshwater fisheries in Asia. The identified fishes largely mirror those found at other Chinese diaspora sites and include freshwater fishes like pikeminnows (Ptychocheilus sp.), Sacramento Blackfish (Orthodon microlepidotus), and Sacramento Perch; North American marine species including rockfishes, flatfishes, and California Sheephead; and Asian marine fishes including threadfin bream and white herring (Ilisha sp.). Although other Chinese diaspora sites occasionally yield fish species not present in the Market Street Chinatown assemblage, the vast majority of taxa found at other Chinese sites in North America are present in this assemblage.

Notably, the Market Street Chinatown faunal assemblage contains 36 vertebrae morphologically determined to belong to genus Channa, a group of carnivorous freshwater fishes known as snakeheads; this genus contains multiple species distributed across much of Asia (Courtenay and Williams Reference Courtenay and Williams2004). Morphological identifications were accomplished using a Northern Snakehead (Channa argus) skeletal specimen from Indiana University's William R. Adams Zooarchaeology Laboratory (specimen #1130015) and three Striped Snakehead (Channa striata) specimens from the lead author's personal comparative collection. Although these species represent the most likely snakehead species to originate in Guangdong, morphological similarities across snakehead species (Voeun Reference Voeun2006) and a lack of comparative specimens from all snakehead species found in Asia necessarily limited morphological identifications to the genus level. All but one of the identified snakehead specimens were recovered from multiple strata in a single wood-lined pit feature in the northwest portion of the site (Feature 86-36/18); based on the size of these vertebrae they represent a minimum of two individuals. Feature 86-36/18 contained a variety of material culture alongside other unusual faunal remains, including a raccoon bone, the majority of salmon (Oncorhynchus sp., a rare taxon in Chinese diaspora assemblages) remains from the site, and a large carnivore tooth that had been sawn and filed, perhaps to shave portions into tea or other preparations (Kennedy Reference Kennedy2016:168–169). Although the exact function of Feature 86-36/18 is unknown, field excavators suggested that, given the presence of what appeared to be ferrous lining used to “rat-proof” the feature, it could have been a belowground storage compartment that was abandoned and used as a communal trash pit sometime before the 1887 fire that destroyed the Market Street Chinatown (Kane Reference Kane2011). According to an 1884 Sanborn Insurance map, Feature 86-36/18 was located near several Chinese-run businesses, tenements, and a theater that were in use variously from the 1870s through 1887, and the feature fill could conceivably relate to any of these buildings. The remaining snakehead specimen came from a pit feature in the southwest portion of the site (Feature 85-31/25) and represents an additional individual. Faunal remains from Feature 85-31/25 have not been fully identified, but archival research and limited analysis of artifacts from the feature suggest that, like Feature 86-36/18, it was used as a communal trash pit by one or more Chinese businesses occupying the area from the 1870s through 1887; these businesses included a gambling house, a “fancy goods store,” and a wood yard (Laffey Reference Laffey1993). Snakehead species have long been used for food in Asia, and they are widely held to have healing properties in southern China (Courtenay and Williams Reference Courtenay and Williams2004). It is tempting to interpret these relatively rare specimens as being part of a potent medicinal preparation, a luxurious ingredient within a special meal, or both. However, the communal nature of trash disposal in both features containing the snakehead bones makes it difficult to decipher the exact use of snakeheads at the Market Street Chinatown.

Regardless of their use, the Market Street Chinatown snakehead specimens are the first and only freshwater Asian fish remains identified in nineteenth-century North American Chinese diaspora sites, and they provide evidence of the sourcing of Asian fishes extending beyond marine waters. However, the inability of morphological analysis to provide species-level identifications of these specimens limits understandings of the geographic extent of snakehead exploitation in the Chinese diaspora fish trade, because many Channa species have different native ranges across Asia. Fortunately, snakehead species are economically and culturally important throughout much of their native ranges, and comparative genetic data from contemporary populations are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information's (NCBI) Genbank for comparison to aDNA data collected from archaeological snakehead specimens. Given this, eight snakehead vertebrae (Figure 1) originating from Features 86-36/18 and 85-31/25 and spanning all three identified individuals, were selected for aDNA analysis with the goal of identifying the snakehead species present in the Market Street Chinatown collection, thereby determining a region of origin based on the species’ native range.

Figure 1. Sample of snakehead bones from Market Street Chinatown Feature 86-36/18 (photo by J. Ryan Kennedy). (Color online)

Materials and Methods

All pre-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) activities were conducted in the aDNA facility at the Laboratories of Molecular Anthropology and Microbiome Research (LMAMR) at the University of Oklahoma. This facility is a dedicated workspace for processing aged, degraded, or low copy number DNA samples. Precautions aimed to minimize and monitor the introduction of contamination are practiced in the laboratory.

DNA Extraction

DNA was extracted from seven snakehead vertebrae from Feature 86-36/18 (designated samples M10-M16) and one snakehead vertebra from Feature 85-31/25 (designated sample M17). Subsamples from each of these vertebrae weighing 34.7–51.0 mg were carefully removed with one-time-use razor blades. All subsamples were submerged in 6% (w/v) sodium hypochlorite for four minutes (Barta et al. Reference Barta, Monroe and Kemp2013). The sodium hypochlorite was poured off, and the samples were quickly submerged twice in DNA-free water. The bone samples were transferred to 1.5 mL tubes, to which aliquots of 500 μL of 0.5M EDTA (pH 8.0) were added, and the tubes were then gently rocked at room temperature for more than 48 hours. An extraction negative control, to which no bone material was added, accompanied the batch of extractions.

DNA was extracted following the method described by Kemp and colleagues (Reference Kemp, Monroe, Judd, Reams and Grier2014). After 90 μL of proteinase K (Green BioResearch) at a concentration of 1 mg/30 μL (or more than 20 units/30 μL) were added to each sample, the tubes were incubated at 64°C–65°C for three hours. Following proteinase K digestion, the tubes were centrifuged at 15,000 revolutions per minute (rpm) for one minute to pellet any undigested bone, dirt, or other solid material. The volumes of liquid were moved to new 1.5 mL tubes, to which 750 μL of 2.5% silica “resin” (i.e., 2.5% celite in 6 M guanidine HCl) and 250 μL of 6 M guanidine HCl were added. The tubes were vortexed multiple times over approximately a two-minute period.

Promega Wizard minicolumns were attached to 3 mL Luer-Lok syringe barrels (minus the plunger) and placed on a vacuum manifold. Three mL of DNA-free water were first pulled across the columns with the intent of washing away any potential contaminating DNA. The mixture of DNA and resin was subsequently pulled across the columns. The silica pelleted on the minicolumns was then rinsed by pulling 3 mL of 80% isopropanol across the columns.

The minicolumns were then placed in new 1.5 mL tubes and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for two minutes to remove excess isopropanol. The minicolumns were transferred to new 1.5 mL tubes, where 50 μL of DNA-free water heated to 64°C–65°C were added to the minicolumns. The minicolumns were incubated at room temperature for three minutes before the DNA was eluted via centrifugation of the tubes for 30 seconds at 10,000 rpm. This step was repeated, amounting to 100 μL of extracted DNA. Ten microliters of the full concentration eluates and extraction negative control were diluted 1:10 and used in PCR, as described next.

Inhibition Test and Repeat Silica Extraction

The full-concentration DNA eluates were tested for the presence of PCR inhibitors following the rationale of Kemp and colleagues (Reference Kemp, Monroe, Judd, Reams and Grier2014) using a “turkey collective” as the aDNA positive control. The control, in this case, was DNA pooled from various extractions of archaeological turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) bones (Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Judd, Monroe, Eerkens, Hilldorfer, Cordray and Schad2017). We decided to pool these individual extractions to reduce variation between turkey DNA eluates in both endogenous mitochondrial DNA copy number and possible inhibitors coextracted with the turkey DNA. Before they were used in experiments, each turkey collective was demonstrated to PCR amplify consistently (in six or more amplifications), hence serving as a positive control.

Fifteen μL inhibition test PCRs amplified a 186 bp portion of the turkey displacement loop (D-loop) using the primers “T15709F” and “T15894R” described by Kemp and colleagues (Reference Kemp, Judd, Monroe, Eerkens, Hilldorfer, Cordray and Schad2017). The components of these PCRs were as follows: 1X Omni Klentaq Reaction Buffer (including a final concentration of 3.5 mM MgCl2), 0.32 mM dNTPs, 0.24 μM of each primer, 0.3 U of Omni Klentaq LA polymerase, and 1.5 μL of turkey collective DNA. These reactions were spiked with 1.5 μL of potentially inhibited, full-concentration DNA eluates from the snakehead vertebrae. The extraction negative controls were also tested for inhibitors in this manner. These PCRs were run in parallel with reactions that contained only turkey collective DNA (i.e., were not spiked). These reactions served as positive controls and allowed us to preclude PCR failure from contributing to our results. PCR negatives also accompanied each round of amplification, allowing us to monitor for possible contamination. Following denaturing at 94°C for three minutes, 60 cycles of PCR were conducted at 94°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 15 seconds, and 68°C (note that this is the optimal extension temperature for Omni Klentaq LA polymerase) for 15 seconds. Finally, a three-minute extension period at 68°C was conducted before bringing the reactions to 10°C.

If the turkey collective failed to amplify when spiked with any given ancient snakehead DNA eluate, we considered the eluate to be inhibited. In the case that spiking the ancient DNA permitted amplification of the turkey collective DNA, we considered that DNA eluate to be free of inhibitors.

Based on the inhibition test described, full-concentration eluates that were deemed to be inhibited were subjected to repeat silica extraction (Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Monroe, Judd, Reams and Grier2014). To the remaining volume of the eluate, 750 μL of 2.5% resin and 250 μL of 6 M guanidine HCl were added. The samples were vortexed numerous times over a two-minute period. The extraction then followed procedures described earlier, except that the volume used to elute the DNA from the column matched the volume being repeat silica extracted. For example, if the starting volume was 87 μL, 43.5 μL of DNA-free water heated to 65°C were added to the minicolumns and left for three minutes before centrifugation. This step was repeated twice for a total volume of 87 μL.

These repeat silica eluates were tested again for inhibition as described earlier. Those still deemed to be inhibited were once again repeat silica extracted and tested again for inhibition. This was carried out until all full-concentration eluates were deemed to be uninhibited.

Snakehead Species Identification and PCR

For snakehead species identification we used primers previously described by Jordan and coworkers (Reference Jordan, Steele and Thorgaard2010) that amplify 189 bp from the mitochondrial 12S gene (relative to a Rainbow Trout [Oncorhynchus mykiss], reference sequence DQ288271.1; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Drew, Weber and Thorgaard2006). The 148 bp sequences produced from these amplicons have been demonstrated to be useful in discriminating a wide variety of bony and cartilaginous fishes, including salmon, smelt, sharks, and cod (Conrad et al. Reference Conrad, DeSilva, Bingham, Kemp, Gobalet, Bruner and Pastron2021; Grier et al. Reference Grier, Flanigan, Winters, Jordan, Lukowski and Kemp2013; Jordan et al. Reference Jordan, Steele and Thorgaard2010; Moss et al. Reference Moss, Judd and Kemp2014; Palmer et al. Reference Palmer, Tushingham and Kemp2018). Note that Jordan and colleagues (Reference Jordan, Steele and Thorgaard2010) originally described their reverse primer in the wrong orientation. The corrected primers are OST12S-F (5′-GCTTAAAACCCAAAGGACTTG-3′) and OST12S-R (5′-CTACACCTCGACCTGACGTT-3′).

Comparative sequence data for this portion of the 12S gene are available from the snakehead species that are both large enough to account for the Market Street Chinatown snakehead specimens and are found in areas where Chinese fishers potentially operated, namely China and Southeast Asia (with example Genbank accession numbers): Black Snakehead (C. melasoma; MN057539.1), Blotched Snakehead (C. maculata; NC020011.1), Bullseye Snakehead (C. marulius; NC022713.1), Emperor Snakehead (C. marulioides; MN057529.1), Forest Snakehead (C. lucius; MF804538.1), Giant Snakehead (MN057550.1), Northern Snakehead (NC015191.1), Ocellated Snakehead (C. pleurophthalma; MN057561.1), Small Snakehead (C. asiatica; NC025225.1), and Striped Snakehead (KU852423.1). According to these comparative sequences, the primers should not largely bias against PCR amplification of these species. The region for annealing the forward primer to Ocellated Snakehead shows an A>G mismatch at the fifth position from the 5′ end of the primer. The other species are 100% matches to the primers.

Full-concentration eluates (deemed to be uninhibited) and the 1:10 dilutions of the original full-concentration DNA eluates were subjected to PCR amplification in 15 μL reactions as follows. First, “standard” PCRs contained 1X Omni Klentaq Reaction Buffer, 0.32 mM dNTPs, 0.24 μM of each primer, 0.3 U of Omni Klentaq LA polymerase, and 1.5 μL of template DNA. Second, we employed a PCR buffer cocktail called PEC-P (DNA Polymerase Technology) that has been found useful in amplifying aged and degraded DNA (Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Bingham, Frome, Labonte, Palmer, Parsons, Gobalet and Rosenthal2020; Palmer et al. Reference Palmer, Tushingham and Kemp2018). PEC-P PCR reactions with Klentaq were 15 μL each, containing 1X Omni Klentaq Reaction Buffer, 0.32 mM dNTPs, 0.24 μM of each primer, 0.3 U of Omni Klentaq LA polymerase, 20% (v/v) PEC-P, and 1.5 μL of template DNA.

Positive amplification was confirmed by separating 2 μL of amplicons on 2% agarose gels stained with GelRed and visualized with UV light. Amplicons were sequenced in both directions at Genewiz (www.genewiz.com). Sequences were subjected to an NCBI BLAST search to determine matches in the database (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Results

DNA was recovered from all eight specimens. Seven samples (M10–12 and M14–M17) exhibited the same haplotype, which was replicated for each sample two to four times. A BLAST search of this haplotype at NCBI found 100% matches to nine entries, eight of which originated from Giant Snakehead (MN057544-MN0575450, KU852424, and KX129904). The ninth match originated from a Striped Snakehead (AY141351) sampled by Chen and colleagues (Reference Wei-Jen, Bonillo and Lecointre2003). This last observation is curious, given that other Striped Snakeheads (e.g., MN057622 and MN057623) are six mutational differences away from Giant Snakeheads in this region of the 12S gene. In addition, the 16S gene sequence produced in Chen and colleagues’ (Reference Wei-Jen, Bonillo and Lecointre2003) study from this Striped Snakehead (AY141421) also matches examples of Giant Snakeheads, again being far removed from examples of Striped Snakehead. These phylogenetic inconsistencies led us to contact the corresponding author of Chen and colleagues’ (Reference Wei-Jen, Bonillo and Lecointre2003) study regarding the Striped Snakehead sample in question. He told us that the “sample came from an aquarium, so it is possible that the original specimen could have been misidentified” (Guillaume Lecointre, personal communication 2020). With this uncertainty, we feel confident in excluding the observation of our haplotype matching to Striped Snakehead. Thus, samples M10–12 and M14–M17 are identified as Giant Snakehead.

From the eighth sample in our study (M13), we were able to produce only a single amplicon. A BLAST search of this haplotype reveals the sequence to be five C>T mutational steps away from the same eight comparative samples of Giant Snakehead noted earlier (with 96.2% identity). This is likely the product of postmortem genetic damage, of which C>T transitions are notably common. However, because we were not able to replicate results for this sample, we could not directly evaluate this possibility. Of all the Channa species for which there are comparative 12S sequences, this sample most closely resembles Giant Snakehead, despite the sequence likely exhibiting damaged nucleotides.

Discussion

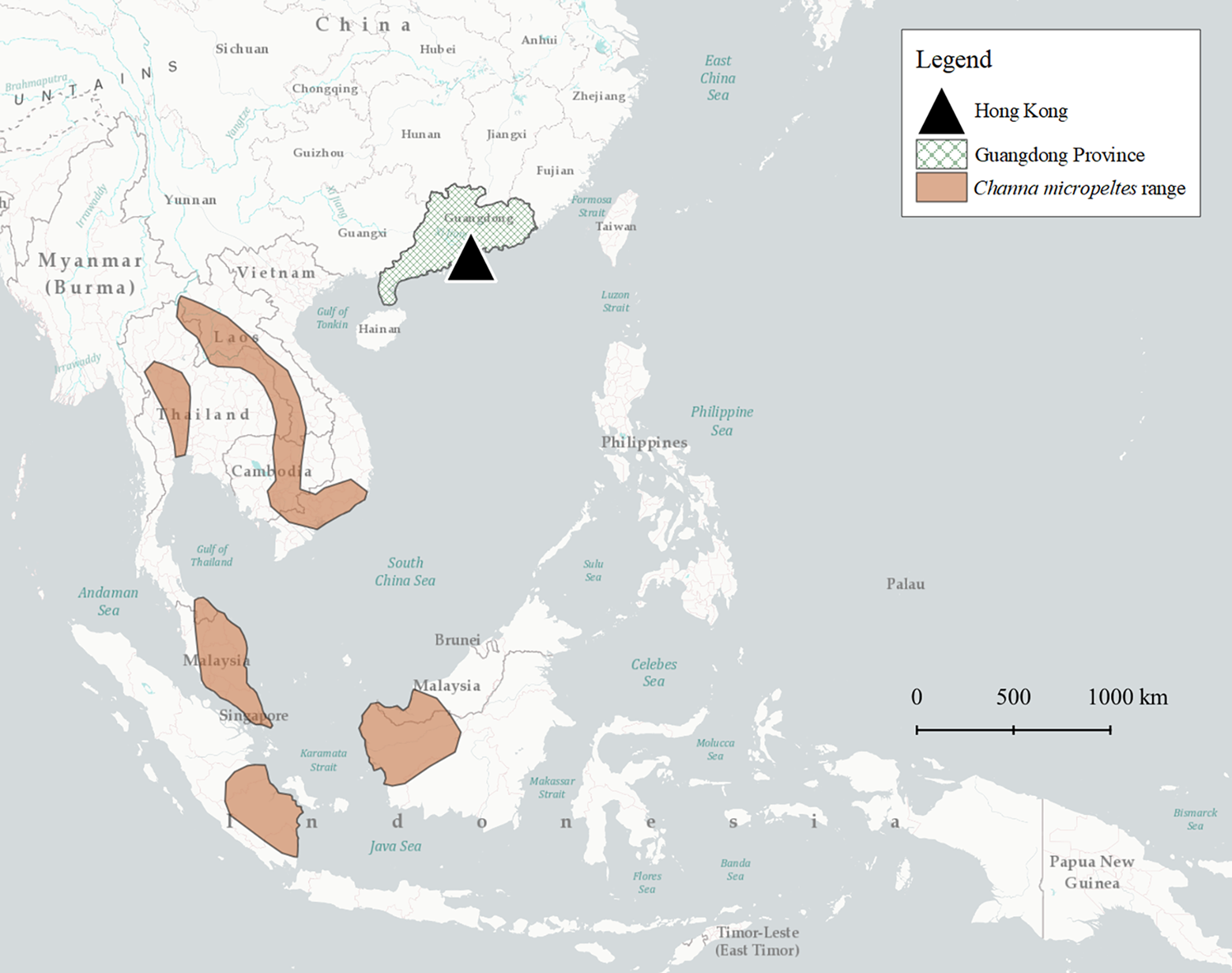

The Giant Snakehead (C. micropeltes) is native to Southeast Asia, rather than to the regions in southern China from where most nineteenth-century Chinese migrants originated (Figures 2 and 3). The identification of this species was initially surprising, given that Kennedy had previously and erroneously speculated that the Market Street Chinatown snakeheads likely derived from one of several Channa species used for food in southern China (e.g., C. striata or C. argus; Kennedy Reference Kennedy2017:433). This assumption mirrors those commonly made by zooarchaeologists in which faunal remains identified to the genus level or higher are assumed to derive from local species or from those thought to be commonly sourced from afar. The identification of Giant Snakehead serves as a cautionary tale against assuming species identifications when multiple osteologically similar species could conceivably be present in an archaeological assemblage. It also documents the first known Asian freshwater fish species imported to nineteenth-century western North America, and it provides important information about the trade networks that supplied Chinese diaspora communities with imported fishes. The identified C. micropeltes specimens would have been caught somewhere in the species’ native range—perhaps in Malaysia or Vietnam where Chinese fishers operated in the nineteenth century (Butcher Reference Butcher2004)—before being dried, shipped to Hong Kong, shipped again to San Francisco, and finally transported south to San Jose. This is a long journey for several pieces of dried snakehead to make, and it would be impossible to trace without the resolution offered by aDNA analysis. The long-distance transport of dried Giant Snakehead is indicative of the cultural value placed on dried fish and snakeheads specifically, regardless of whether the Market Street Chinatown snakeheads were ultimately used for food, medicine, or both.

Figure 2. Map of the native range of Channa micropeltes (following Courtenay and Williams Reference Courtenay and Williams2004).

Figure 3. Image of Channa micropeltes (photo by George Chernilevsky, public domain). (Color online)

In the context of Chinese diaspora fishing practices, the identification of Giant Snakehead hints at the critical roles that both Chinese fishers and jinshanzhuang played in bringing this fish to San Jose. Chinese fishers relied on Chinese fishing technologies and the shareholding business model to adapt their fishing strategies to local ecological, social, and political conditions while simultaneously responding to market demands in China for a diverse array of fish products. Chinese fishers tended to employ generalist fishing technologies including bag nets, seines, and hook-and-line that could be flexibly employed to match local needs. Although Chinese fishing communities often focused on a core group of local fishes, their generalist methods ensured that they caught many additional species that could be dried and distributed throughout the diaspora. In the case of Giant Snakehead, Chinese fishers living in Southeast Asia were able to take advantage of the availability of this species, a fish similar to snakehead species native to Guangdong, to produce dried fish that had market value. However, moving Giant Snakehead from Southeast Asia required the services of jinshanzhuang and their agents who acted as intermediaries and suppliers, facilitating the movement of finished products from overseas to China, and vice versa. The identification of Giant Snakehead in the Market Street Chinatown reveals for the first time that jinshanzhuang further redistributed fish (and likely other products) shipped to Hong Kong to new locations throughout the diaspora, making Hong Kong a critical node in trade networks that effectively spanned the Pacific World.

Previous studies of nineteenth-century Chinese fishing practices, especially those using data from North American Chinese diaspora sites, have largely emphasized bidirectional flows of goods between North America and Hong Kong (see Kennedy Reference Kennedy2017). Little consideration has been given to the potential for fish outside the area immediately surrounding Hong Kong, in large part due to the inability of North American zooarchaeologists to identify imported Asian fishes with discrete ranges in Chinese diaspora assemblages. The presence of Giant Snakehead in the Market Street Chinatown faunal assemblage challenges assumptions of a largely Hong Kong-to-San Francisco trade and reveals greater complexity in the sourcing of fish products consumed in nineteenth-century Chinese diaspora sites than previously known. These findings indicate the potential for aDNA analyses of other imported Asian fishes identified at Chinese diaspora sites to further contribute to understandings of Chinese fishing and the distribution of fishes in the nineteenth-century Pacific World. This is especially true for commonly recovered Asian fish taxa typically identified to the genus level, such as threadfin bream and white herring; refining the exact species present for these and other types of imported Asian fishes will help identify additional, more specific sources of fish that supplied Chinese diaspora communities and in turn facilitate a fuller understanding of Chinese fishing practices and fish trade.

More importantly, the identification of Giant Snakehead remains has implications for using Chinese diaspora fishing data in comparative studies of nineteenth-century fishing worldwide. At the beginning of this article, we noted the difficulty in comparing Chinese diaspora fishing practices and trade with the better-documented collection and distribution of North Atlantic species like Atlantic Cod. The following brief discussion demonstrates how increased knowledge of Chinese fishing practices can provide useful data against which to compare the better-understood fisheries of the North Atlantic.

Extensive archaeological studies of the Atlantic Cod trade include investigations of cod fishing and processing alongside extensive evidence of cod remains at inland consumer sites (e.g., Barrett and Orton Reference Barrett and Orton2016; Orton et al. Reference Orton, Morris, Locker and Barrett2014). Together, these data speak to the targeted collection and large-scale trade of Atlantic Cod across the Atlantic World by fishers who, over time and through the industrialization of fishing, became highly specialized in the collection of this species. A plethora of zooarchaeological, genetic, and stable isotope studies have revealed the impact that fishing had on Atlantic Cod by documenting how intensification of cod fishing, changing/expanding fishing locations, and overfishing resulted in decreasing average size and genetic diversity of cod over time (e.g., Amorosi et al. Reference Amorosi, McGovern and Perdikaris1994; Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Orton, Johnstone, Harland, Van Neer, Ervynck and Roberts2011; Betts et al. Reference Betts, Maschner, Clark, Moss and Cannon2011; Kess et al. Reference Kess, Bentzen, Lehnert, Sylvester, Lien, Kent and Sinclair-Waters2019; Ólafsdóttir Reference Ólafsdóttir, Pétursdóttir, Bárðarson and Edvardsson2017; Orton et al. Reference Orton, Makowiecki, de Roo, Johnstone, Harland, Jonsson and Heinrich2011). Likewise, the recovery of large numbers of Atlantic Herring remains from sites across Europe and North America demonstrates similar themes in the collection and distribution of this species (Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Locker and Roberts2004; Enghoff Reference Enghoff2000; Makowiecki et al. Reference Makowiecki, Orton, Barrett, Barrett and Orton2016). Together, archaeological and historical evidence of fishing in the North Atlantic, especially during the nineteenth century, indicate highly specialized, large-scale extraction of a core group of fishes, most notably Atlantic Cod. Increasing demand and natural and human-driven changes in Atlantic Cod migration routes and spawning locations in the past necessitated adaptations to reduced availability of fish stocks; fishers responded with a variety of strategies, including the importation of fish, local fishing intensification, migration to access more productive fishing grounds, and the development of new technologies to better access Atlantic Cod stocks (e.g., Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Orton, Johnstone, Harland, Van Neer, Ervynck and Roberts2011; Edvardsson et al. Reference Edvardsson, Patterson, Bárðarson, Timsic and Ólafsdóttir2021; Pope Reference Pope, Roy and Côté2004). These strategies were driven at least partially by the high degree of specialization among Atlantic Cod fishers; rather than diversifying the range of species caught, these fishers typically pursued Atlantic Cod across new fishing grounds or with new technologies.

The identification of Giant Snakehead in the Market Street Chinatown collection, along with existing Chinese diaspora zooarchaeological data, reveals several ways that nineteenth-century Chinese diaspora fishing practices differed from those of the North Atlantic. Whereas industrial-scale fishing in the North Atlantic focused on a relatively narrow range of species, zooarchaeological data from Chinese diaspora sites demonstrate that Chinese fishers used generalist fishing strategies to collect a much wider range of species that varied based on the locations in which they operated. In North America, this included dozens of fish species spread across marine and freshwater habitats: the identification of numerous Asian marine fishes alongside Giant Snakehead in the Market Street Chinatown assemblage documents a similar pattern of diverse fishing throughout Asian fisheries operated by Chinese fishers. The identification of Giant Snakehead also reveals how disparate, small-scale Chinese fishing operations contributed to the large-scale fish trade supplying diaspora communities throughout the Pacific World. The diversity of fish caught and of the locations used by Chinese fishers was made possible by the use of highly adaptable methods and a shareholding business model that provided small groups of Chinese fishers the flexibility to move into new environments and make use of fish species that might otherwise have been economically unviable for larger-scale, more specialized fishing operations like those of the North Atlantic. Further, Chinese consumer demand for diverse fish products ensured that Chinese fishers would likely find multiple economically valuable fish species wherever they moved to in the Pacific World. Although migration played a central role in Chinese Pacific World fishing, the generalist fishing methods employed resulted in the core group of fishes taken by Chinese fishers varying greatly based on local available species. Despite operating at a small-scale, artisanal capacity, Chinese fishers were able to distribute their catch throughout the diaspora by taking advantage of the services of jinshanzhuang, who effectively served as intermediaries to move a diverse array of seafood products around the Pacific World and translate them into commodities for consumers to buy (see Tsing Reference Tsing2015).

The fundamental differences between North Atlantic and Chinese diaspora fisheries have implications for understanding long-term trends in fishing strategies in both contexts. When faced with changing fisheries or an inability to meet demand, fishers follow a range of strategies, including intensifying fishing efforts, diversifying fishes caught, and changing fishing grounds. In the case of nineteenth-century North Atlantic fisheries, fishers typically intensified local fishing efforts and, when the need or opportunity arose, migrated to new fishing grounds to take advantage of less heavily fished stocks. This contrasts with strategies used in the broader Chinese Pacific World, in which fishers utilized migration to target a diverse array of fishes across a range of locations. Although individual Chinese fishing communities would often focus on a core group of fishes (e.g., collecting rockfish and flatfish in California), when placed in the broader context of the nineteenth-century Cantonese Pacific, these fishing operations were part of a highly flexible and diverse set of fishing operations that collected myriad marine and freshwater fishes throughout the Pacific World.

Present-day concerns about the effects of overfishing and climate change have led to increasing interest in understanding the strategies employed by fishers around the world in the face of changes in fisheries (e.g., Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Samhouri, Stoll, Levin and Watson2017; Perry et al. Reference Perry, Ommer, Barange, Jentoft, Neis and Sumaila2011). As noted earlier, such strategies include diversification, intensification, and migration; the specific strategy employed is driven by a range of factors, including economic stability, initial fishing strategies (e.g., generalist versus specialist fishers), environmental knowledge, and so on. This comparison between the fisheries of the nineteenth-century North Atlantic and the Pacific World indicates that a more detailed analysis of long-term fishing adaptations in these two contexts has the potential to contribute important knowledge about fishers’ strategies across two very different modes of fishing that both operated at transnational scales.

Conclusion

We presented genetic identification of Giant Snakehead remains in the Market Street Chinatown and placed these data within the context of nineteenth-century Chinese fishing in the Pacific World. This study reveals the first archaeological evidence of the trade of fish from Southeast Asia to the United States, highlighting the critical role of jinshanzhuang in redistributing goods throughout the Chinese diaspora. Further, these results reveal the flexibility of the small shareholding business model, a critical technology used in a range of contexts across the Cantonese Pacific (see Yu Reference Yu, Rose and Kennedy2020). These two factors—a flexible business model and ready transportation of products—allowed Chinese migrants to transplant fishing operations to a diverse array of locations and adapt them to local conditions.

Although the identification of Giant Snakehead in the Market Street Chinatown assemblage reveals clear ways that nineteenth-century Chinese Pacific World fisheries differed from those in the North Atlantic, more work still needs to be done to fully compare fishing in these two contexts. Ancient DNA analysis to identify more Asian fish specimens present in North American Chinese diaspora sites to the species level will help build a fuller picture of the sources of fish traded across the diaspora, and more fish assemblages from primary fishing contexts like the Point Alones fishing village in Monterey Bay, California, must be analyzed. Identifying and analyzing more such fish assemblages, especially in non-North American contexts, will be critical to building a more robust understanding of how Chinese fishing strategies were employed across a range of locations and how they changed through time. Ultimately, archaeologists need a variety of datasets to fully explore the corresponding variety of fishing locations and species targeted by nineteenth-century Chinese fishers.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted as part of the Market Street Chinatown Archaeology Project, a community-based research and education collaboration between Stanford University, the Chinese Historical and Cultural Project, History San José, and Environmental Science Associates. We would like to thank the members of Market Street Chinatown Archaeology Project for encouraging this work on the Market Street Chinatown collection. Funding for this work was provided by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research (grant no. 8747) and the Lang Fund for Environmental Anthropology at Stanford University. Barbara Voss, Susan deFrance, Connie Young Yu, and two anonymous reviewers provided feedback that greatly strengthened this article. Many thanks to Cara Monroe for assistance in the LMAMR, Sam Couch for help during morphological analysis, and Alex Badillo for help with translations.

Data Availability Statement

All data included in this study are provided in the text. See GenBank for reference sequences.