Introduction

During crisis management actors are subjected to different types of pressures driven by some factors (politics; time; media; environment; etc.). Those can lead to potentially dangerous or catastrophic results. Among these factors are the stress and its different impacts on the managers and actors. The challenge of this study is to identify if experience feedback of stress impact in crisis management can help in training, in order to prepare actors to reduce this impact and its consequences. Therefore, the main questions can be:

• Is it possible to predict the impact of the stress in this type of situation?

• How can experience feedback representation help in this type of prediction?

• How to build training situations based on failures and success based on experience feedback?

In this paper, some answers to these questions are explored, especially, the representation of experience feedback with stress impact in crisis management. First, a description of crisis management as a systematic and cooperative situation is shown. Then, the stress in this type of situation is discussed and a representation of the structure of experience feedback in crisis management is proposed. This study is illustrated in a real case of a terrorist attack crisis management in Algeria during a civil war. Finally, a fuzzy set generator has specified that help to predict different states of stress impact.

Crisis management

Crisis definition and crisis management

The crisis is an unstable and dangerous situation affecting individual, group, community, and the whole society. It generated a collective stress (Rosenthal et al., Reference Rosenthal, Charles and Hart1989). It is an exceptional situation. One of the definitions of crisis is: “a serious threat to the basic structures the fundamental values and, norms which under time pressure and, highly uncertain circumstances necessitates making a critical decision” (Rosenthal et al., Reference Rosenthal, Charles and Hart1989). Many types of crises exist, as political, the contaminated blood crisis (Michel, Reference Michel1993); economic and financial, the Enron financial scandals (Rosenthal, Kouzmin, Reference Rosenthal and Kouzmin1997); technological, Challenger (Starbuck and Milliken, Reference Starbuck and Milliken1988); environmental crisis, Bhopal (Shrivastava, Reference Shrivastava1987), Chernobyl (Beck, Reference Beck1992) and, Exxon Valdez (Pauchant and Mitroff, Reference Pauchant and Mitroff1992). Crisis can have international, domestic and, local dimensions. A crisis requests an organization to manage it and, to make pertinent decisions with the aim to request from this situation or to reduce its effect in a short time with minimal damage.

Crisis management as a complex and dynamic system

During the crisis (i) operational actors as firefighters, police, rescuers, and doctors are required to manage the situation; (ii) some financial resources are to be allocated; (iii) logistical resources have to be in place to ensure food, water, tent, fuel, and medicaments for the victims; and (iv) technical resources as medical equipment, communication equipment, and evacuation means are made available to the authority charged to manage the crisis.

This personal, during all operations, comes from different organizations, governmental organization (Government, police, army, etc.) or non-governmental organization (Red Cross, MDM, MSF, etc.). Actors in this type of organization have different experiences, culture, methods, approaches, objectives, and visions. During crisis management, actors are invited to work, communicate, cooperate, coordinate, and exchange their own experiences. Therefore, the crisis management is a hard and complex process. In addition to that, crises evolve over time and in some cases over the space. In this type of situation, dimensions such as media, public, and political pressures will also be considered. Actors have to deal with different factors (environment; time; space; personnel; methods; objectives; culture; roles; etc.). Lagadec (Reference Lagadec1991) illustrates that in his work as these dimensions: “The plurality of actors, the importance of the consequences (deaths, serious injuries), the complexity and the disparity of situations to be managed and their rarity make that the actors are quickly overburdened and do not manage to face up efficiently to this event types. Crisis management consists in dealing with the complexity and the interdependency of systems, especially, with the combination of events.” These different descriptions have been conducted in this study to show interest in the systemic, and in particular, systemic analysis.

The systemic analysis considers that a system can be composed of objects or subsystem; the system is complex; it has a purpose and an environment; evolves over time and, the system has some feedback for his regulation. Jean-Louis Le Moigne mentioned the system well, “An object is in an environment, have purposes, exercise activity and sees its internal structure evolving over time, without it loses nevertheless his unique identity” (Le Moigne, Reference Le Moigne1994).

Considering all of this, the crisis management can be described as a system:

(a) It is composed of a set of interactive elements or an assembly of subsystems (human resources, financial resources, technical resources, and organizational resources);

(b) It is complex because it is characterized by its unpredictability, uncertainty, and random behavior;

(c) It has a purpose or an objective to request off or reduce the effect of the crisis situation in a short time and with minimal damage;

(d) It has an environment. The crisis is under the influence of economic, social, political, environmental factors;

(e) It has an activity. This activity is to manage the crisis and prepare the post-crisis;

(f) It evolves over time: the crisis situation changes as soon as problems occur, or additional needs, or information over situations change, etc.;

(g) It has some feedback, because the mechanism sends back to the entrance of the system in the form of data, the information depends directly on the exit of the interaction (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Crisis management model.

Using feedback in crisis management

The feedback is one of the main concepts of the systemic coming from cybernetics. It is a key process of active organization. It helps the organization to be reproductive, generic, and generative (Morin, Reference Morin2013). There are two main types of feedback: positive (runaway) and negative (equilibrium). The latter one is discussed in this paper. The negative feedback is the regulation by introducing an informational system by detection and correction of errors. Edgar Morin explains that by: “Any organization contains a regulation which tends to cancel the disturbances or the abnormalities which appear related to the whole process and the organization” (Morin, Reference Morin2013). The feedback concept is used in several fields such as biology, mechanics, psychiatry, mathematics, etc. (Von Bertalanffy, Reference Von Bertalanffy1972).

The purpose of the crisis management is to obtain a nominal situation as close as the situation prevailing before the crisis. For that, crisis management actors, using crisis information, means, and capacities, adjust their approaches, procedures, methods, organizations, means to try to obtain a normal situation by correcting decisions, and action. If it is not reached, they repeat these operations of regulation as often as it is necessary (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. The negative feedback in crisis management.

Crisis management as collaborative activity

As indicated previously, during a crisis management, the actors come from different organizations. They work, communicate, cooperate, coordinate and, exchange their own experiences. Their main common objective is how to deal with the crisis for reducing its effect? In this relationship, is noted that multiple actors are interdependent in their work. They interact with each other to improve the state of their common field. In Computer-Supported Cooperative Work, this activity is defined as: “distributed in the sense that decision-making agents are semi-autonomous in their work in terms of contingencies, criteria, methods, specialties, perspectives, heuristics, interests, motives and so forth” (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt1994). Thus, they use resources such as computers; plans; procedures; schemes; etc. This distributed activity can be represented as Triple C (Communication, Coordination, Cooperation). Several papers in the literature mention the role of Triple C in crisis management, and their interdependence (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Nolte and Vitolo2016). The interdependence of the 3C is affected by the regulation. Indeed, the regulation adjusting consists of sending or to receiving information, giving a warning (Communication); using means (Coordination); and the procedure, decision, and organization (Cooperation) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. The Triple C and the regulation.

Representing the situation of crisis management

Considering time evolution; environment changes; and cooperative activity; the control of actions is very difficult. That depends on different factors such as situation misunderstanding; previous experience missing; actors stress, political and economic environment, etc. The crisis can be so represented as relations between event and states respecting this dynamicity (Sediri et al., Reference Sediri, Matta, Loriette and Hugerot2013). Each state can be defined as an event/consequences (Sediri et al., Reference Sediri, Matta, Loriette and Hugerot2013). A state can generate events and events can modify states and so on (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Representing a situation as a sequence of states and events.

Five crisis management efforts are defined (Pauchant, Mitroff and Lagadec, Reference Pauchant, Mitroff and Lagadec1991): (1) strategic efforts; (2) technical and structural efforts; (3) efforts in evaluation and diagnosis; (4) communication efforts; and (5) psychological and cultural efforts. Stress is an important element to consider related to the psychological and cultural efforts. Linked to this, this research study showed interest on stress impact in crisis management.

Stress in crisis management

Stress and coping strategy

As is noted above, the stress is an important factor in the success or the failure of decision-making in a situation of crisis management. It is a particular relation between an actor and his specific environment. Its evaluation can be weak or exceed the actor resources and can be endangered his well-being (Lazarus and Folkman, Reference Lazarus and Folkman1984). It was noticed that “Some policymakers reveal resourcefulness in crisis situations seldom seen in their day-to-day activities; others appear erratic, devoid of sound judgment, and disconnected” (Hermann, Reference Hermann1979). Several approaches for the stress have been proposed, based on response (Selye, Reference Selye1974); stimulus (Bruchon-Schweitzer et al., Reference Bruchon-Schweitzer, Rascle, Quintard, Nuissier, Cousson and Aguerre1997); the interactionism (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Bright and Clow2001); and transactional approach (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Griffiths and Rial-González2000).

In the case of this study, the transactional approach is chosen. It is related to cognitive and emotional processes, which gives interaction between a person and his environment (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Griffiths and Rial-González2000; Steiler and Rosnet, Reference Steiler and Rosnet2011). This indicates that the individual and the demand are two components. These define themselves in a continuous process with a retroactive loop. More concretely, the stress result from the imbalance observed during the cognitive evaluation between the demand and, the capacity to deal with.

Indeed, an actor possesses personal characteristics that differentiate him from others. He is under the influence of environmental variables. When there is a stimulus and, when a particular situation can put the actor in danger, he starts a process evaluation. This process has a primary evaluation, the actor wonder, “am I OK? Or I am in a potential danger” and, the secondary evaluation begins where the actor wonders by which way he can go out from this situation. This evaluation orients the strategies of the coping, in whom the objective is either to decrease the tension resulting from the situation, or to modify the situation (Paulhan, Reference Paulhan1992). Lazarus and Folkman (Reference Lazarus and Folkman1984) defined the coping as “the overall cognitive and behavioral efforts, continuously changing, deployed by an actor for managing specific internal and/or external requirements, which are evaluated as consuming or exceeding his resource” (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Representing stress and coping strategy.

There are different studies that propose training and mental preparation methods to help actors to face the stress in crisis management (Pauchant et al., Reference Pauchant, Mitroff and Lagadec1991; Cibiel, Reference Cibiel1999; Ducrocq et al., Reference Ducrocq, Vaiva, Cottencin, Molenda and Bailly2000). This paper focuses on the impact of stress on decision-making in order to promote learning from fails and guides based on experience feedback.

The impact of the stress on decision-making in a crisis situation

Bruchon-Schweitzer et al. (Reference Bruchon-Schweitzer, Rascle, Quintard, Nuissier, Cousson and Aguerre1997) present four classes of indicators that influence stress conditions:

• Task conditions: workload, etc.

• Relational conditions: conflict, harassment, etc.

• Job conditions: Mobility, no promotion, etc.

• Interaction private/profession: husband, children, family, etc.

Different observable indicators of the stress are considered in psychology as manifestations of stress. Some of these are mainly noted:

• Speech rhythm (Kanfer, Reference Kanfer1959; Siegman and Pope, Reference Siegman and Pope2016), repetition of expressions and words (Osgood and Walker, Reference Osgood and Walker1959; Kasl and Mahl, Reference Kasl and Mahl1965), using specific words (Kasl and Mahl, Reference Kasl and Mahl1965; Lalljee and Cook, Reference Lalljee and Cook1973; Siegman and Pope, Reference Siegman and Pope2016) etc.;

• Super activity, inadequate movement (Dittmann, Reference Dittmann1962; Mehrabian and Ksionzky, Reference Mehrabian and Ksionzky1972) etc.;

• Silence (Weintraub and Aronson, Reference Weintraub and Aronson1967; Aronson and Weintraub, Reference Aronson and Weintraub1972);

• Ambivalence, self-confidence (Osgood and Walker, Reference Osgood and Walker1959; Eichler, Reference Eichler1965; Aronson and Weintraub, Reference Aronson and Weintraub1972);

• Hostility and aggression (Murray, Reference Murray1954; Gottschalk et al., Reference Gottschalk, Winget, Gleser and Springer1966);

• Inappropriate behavior and actions (Mehrabian, Reference Mehrabian1968b, Reference Mehrabian1968a).

Other studies have shown some manifestations of stress impact on decision-making as:

• Situation and context simplification (Holsti et al., Reference Holsti, Brody and North1964; Lazarus et al., Reference Lazarus, Opton and Spielberger1966);

• Fixation on one possibility without any flexibility and alternatives (Berkowitz, Reference Berkowitz1962; Holsti et al., Reference Holsti, Brody and North1964; Rosenblatt, Reference Rosenblatt1964; De Rivera, Reference De Rivera1968);

• Consulting several opinions without concluding on a decision (Holsti, Reference Holsti1972; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Sloan and Williams1988);

• Imposing a decision without measuring the impact and the consequences (Korchin, Reference Korchin1964; Holsti, Reference Holsti1972);

• Missing decision-making and actions (Holsti, Reference Holsti1972; Schlenker and Miller, Reference Schlenker and Miller1977).

In this work, some of these indicators that can be measured directly from crisis management actions feedback are selected:

• Super activity and imposing decision without considering the impact;

• Silence, missing decision, and actions;

• Speech rhythm, aggression, and conflict of opinions and decisions;

• Simplification of the situation and inadequate means and actions.

The main aim of this study is to provide a learning system showing stress impact on crisis management using experience feedback. The following section presents the main principles of this system.

Using feedback in stress situation

A crisis is by definition a stressed situation, outside of control. Therefore, stress is an important element to take into account when dealing with this type of situation. For instance, different manifestations of the stress such as silence or aggression are present. In addition, impacts such as simplification of the situation or consulting several opinions without concluding on a decision are noted. These impacts influence the decision-making. Related to each act and decision, stress can be increased or be reduced depending on the result of the decision and, in the state of actors. Here, the negative feedback comes into.

Using experience feedback to manage stress impact

Using experience feedback in crisis management

In the daily life and, for any problem or situation, experience feedback is used. Yet, knowledge management approaches define some techniques to promote learning from experience feedback. Therefore, Foguem et al. present experience feedback as a “process of knowledge capitalization and exploitation mainly aimed at transforming understanding gained by experience into knowledge” (Foguem et al., Reference Foguem, Coudert, Béler and Geneste2008). This process shows five distinguished information: events, context, analysis, solutions, and lessons learned. The literature on this domain has highlighted several tools to help companies and organizations, to avoid past mistakes and, to benefit from all the knowledge and the know-how used (Nonaka and Takeuchi, Reference Nonaka and Takeuchi1995; Grundstein, Reference Grundstein2000; Dieng-Kuntz and Matta, Reference Dieng-Kuntz and Matta2002; Sediri et al., Reference Sediri, Matta, Loriette and Hugerot2013).

By including experience feedback on technical and organizational means, actors can learn how to face stress in crisis management. Then, an actor or a group of actors can adjust its approaches; policies; procedures; methods; models and its organization, guided by previous experiences, to try to obtain as possible as a nominal situation (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. The experience feedback in crisis management.

For the follow-up study, the knowledge management techniques are used in order to capture and represent experience feedback in stressed situations.

Capture a situation

The knowledge management

The Human Knowledge can be defined as information combined with experience context interpretation and reflection (Davenport et al., Reference Davenport, De Long and Beers1998). There are two forms of knowledge: (i) the tacit knowledge: that is difficult to articulate, to put in words, text or to drawing and; (ii) the explicit knowledge, that it can be illustrated by different forms such as words, images, documents, video, or audio recording (Dalkir and Liebowitz, Reference Dalkir and Liebowitz2011).

The Knowledge Management is used to identify and leverage the know-how, experience and, other intellectual capital knowledge for performing the organization (Ruggles, Reference Ruggles1998; Foguem et al., Reference Foguem, Coudert, Béler and Geneste2008). It is then coordination between people, technology, process, and organizational structure in order to add value through reuse experience and innovation (Dalkir and Liebowitz, Reference Dalkir and Liebowitz2011). The aim of knowledge management is to make explicit some of tacit knowledge. For that, some of knowledge management approaches use a wide variety of techniques to capture knowledge inherited from knowledge engineering (Wielinga et al., Reference Wielinga, Schreiber and Breuker1992) such as interviews, text mining, knowledge modeling, etc.

Capture a knowledge

For this study, the authors interview crisis management experts. It is noted that one of the authors is considered as an expert, he is a retired officer of the army. During this tragedy he was an Officer of the Tactical Staff Army and the case studied is his own experience. The expert is the one who has a good mastery of his activity and is considered a reference by his colleagues (Bogner and Menz, Reference Bogner and Menz2009). For collecting information, an interview with the expert is done. Hitzler defined the expert as a person who possesses an “institutionalized authority to construct reality” (Hitzler, Reference Hitzler2013). Several primitives can be used (concept, relations, task, etc.) to model results of interviews. For this work, the situation representation as states and events is used. Before showing how experience feedback can be used in stress impact state predictions, let us illustrate the capture and to represent a crisis management knowledge on a real case.

Real case study with the stress

A case study in real experience in a situation of crisis management can reveal some aspects of the impact of the stress during this event. It also provides, a timeline for actors’ reaction with a general view on errors committed, means used, the places where the event was reported and, different information and data known.

Case description

A lieutenant of Algerian Army explains, in this case, his experience about a terrorist attack on two villages “Ramkaa and Had El Chekala” (red circle on the map, Fig. 7), in the Algerian mountain. In fact, the army had to deal with a group of terrorists in the area. The tactical command post was installed near the mountain (blue flag on the map, Fig. 9), in order to prepare their track. In the morning (6 AM) of a day in February, some soldiers had been awake by a young man running to the camp and crying: “They killed them, they killed them.” Soldiers tried to calm the young man and conducted him to the nursery. The crowd woke colonel and lieutenant. The young man explained then that terrorists killed all people in his village. Colonel asked the lieutenant to prepare three cars, and they went directly to villages with only simple guns. They drove on a winding road. Terrorist crowd was everywhere and could be attacking them. Arriving at the village, they discover horrible landscape, “dead persons everywhere, disemboweled women, blood, etc.” They were shocked and did not believe their eyes. One of the Chiefs was saying nonsense words. Soldiers removed their weapons, they were afraid about his safety. The Colonel decided then to visit the nearby village with the lieutenant and some soldiers. They discovered the same horrible situations, adding to that, the school was burned with the nursery and the post-office. The colonel sat on the ground without moving. Soldiers and Lieutenant did not have any idea on how to react and what to do. Their radio did not work. There was no network. They stayed in this state more than an hour and a half. Then, other soldiers arrived at the base of ambulances and radio-communication post because they guess that their colleagues needed help after 2 h of silence. After that, the colonel recovered his senses and called the government crisis cells. He called the tactical command post to send him firefighters and medical emergency resources. It was about 10 AM. Crisis cells were installed at Ramkaa village. Dead bodies were gathered. They discovered some survivals, who received first aid on site. Helicopters arrived and first evacuations started at 1 PM.

Fig. 7. Map, showing the positions of the terrorist attack and the tactical command post.

Case analysis

This case was analyzed using the stress indicators noted above.

• Imposing a decision without measuring the impact and the consequences: The colonel took three vehicles with simple guns and went to the village. He decided then to visit the nearby village with the lieutenant and some soldiers.

• Repetition of expressions and words: One of the Chiefs was saying nonsense words.

• Silence, missing decision, and actions: The colonel sat on the ground without moving. Soldiers and Lieutenant did not have any idea on how to react and what to do.

• Simplification of the situation and inadequate means and actions: With simple guns, they went to villages. Their radio did not work. There was no network.

The first impact of this stress: time-lost, wounded died (waiting from 6 AM to 1 PM). The first soldiers can be attacked and killed by terrorists on the road and in the villages, they were lucky. No communications between operational and tactical teams.

Case modeling

In this case, as already mentioned, can be modeled as events/states with which impact of stress is represented. The impact of stress can be discovered when exploring different paths through events and states (Fig. 8). For instance, taking three vehicles of soldiers with small guns as cooperation, the decision can have consequences such as wounded soldiers on the road. For instance, silence and no action, as coordination, it is a waste of time.

Fig. 8. Case modeling.

Experience feedback case representation

After analyzing the same case using experience feedback and in an implicit manner the negative feedback, different regulation actions can be identified.

Regulation and correct case description

The corrected description starts when the young man gives the alert. At this moment, the Colonel will give the order to:

• A Reconnaissance Unit, accompanied by mine sweeper experts, got ready to go to see what happened?

• The Medical units got ready for a possible intervention in villages (field hospital, ambulances, helicopters of evacuation, etc.).

• The hospitals around the city activated their plans of reception of the wounded victims.

Half an hour after, the unit of reconnaissance was ready and moved toward villages. On the road, this unity had the capability to counter a terrorist attack. Once there, the head of unit confirms information to the Colonel and begins to secure villages to try to help survivors. The colonel at this moment will give:

• Order to the medical units to move to the village to be able to save lives and evacuate the wounded victims.

• Adapt its general staff to the situation to become a cell of emergency management.

At 9 AM operations and the evacuations toward different hospitals began.

Regulation case modeling

For this modeling (Fig. 9), the authors take back the stress impact model by using the same concept event/state. In this model, there was no time lost or moments of fluctuations due to uncertainties in the behavior and in the decision-making. The reconnaissance unit sent to the villages was ready for any terrorist attack. The medical units and the hospitals had the alert at the convenient moment. They had time to get ready. The tactical post command was adapted to the situation to become a cell of emergency management. The most important of all is that the Colonel makes the right decisions at the right time. He did not lose time to save lives. He also preserved his security and the security of his soldiers.

Fig. 9. Case modeling with feedback experience.

It is evidence that stress will always be present in crisis. The aim of this study is to show at each step: the stress impact actions and, their consequences; and also, the right actions and their consequences in the situation of crisis. By combining the two models (Figs. 8, 9) and learning from errors, actors try to avoid bad decisions. These should ensure the actors to return to the nominal situation as soon as possible.

Figure 10 shows an example of one state/event. The process, in the red color, represents the bad actor reaction to events and states. Taking into account the experience feedback, the actors react differently and make the best decisions, which will be saved a substantial time and maybe human lives (process in green). This view of these different situations concerns only the vision of the team of the tactical headquarters and the military engaged in this situation. This type of representation can help to apply prediction algorithms in order to propose a simulation of stressful situations in a learning space. Before presenting our state prediction approach, let us first compare some prediction techniques.

Fig. 10. Stress impact with and without feedback experience.

Techniques for prediction

This study as is explicated above tries to supply the impact of the stress and its consequences on the crisis management based on real experience. The next step is to identify or to find the method that may allow the prediction of these consequences.

There is a large volume of published studies describing the role of prediction in industrial systems and especially by using Artificial Intelligence techniques. We found different kinds of tools such as expert systems; statistical tools; case-based reasoning; neural networks; fuzzy set; and neuro-fuzzy networks (Racoceanu, Reference Racoceanu2006). Table 1 shows the advantage and the disadvantage of these different kinds of tools.

Table 1. Advantage and inconvenient of prediction technic

These are considering as basic tools for decision-making. In our case, the kind of prediction is complex and more difficult to characterize. It requires the appropriate use of human behavior; numerical value; and semantic data. This type of prediction should be near to reality. These different parameters and difficulties motivated us to choose the fuzzy sets.

The fuzzy sets

It is a mathematical theory of Lotfi Zadeh (Zadeh, Reference Zadeh1996) based on intuitive reasoning. This theory considers the subjectivity and the imprecision. It may treat digital literacy; non-measurable values and for a linguistic issue (Bouchon-Meunier and Zadeh, Reference Bouchon-Meunier and Zadeh1995). Fuzzy sets provide techniques to represent subjective and uncertain reasoning. Its goal is to build a formal system that it can make a qualitative reasoning (Rosental, Reference Rosental1998). The fuzzy sets are used in different domains such as pattern recognition, robotics, biology, economy, medicine, ecology, etc. (Zimmermann, Reference Zimmermann2010)

Fuzzy sets principles

Zadeh defined the fuzzy set (Zadeh, Reference Zadeh1996) by:

“Let X be a space of points, with a generic element of X denoted by x. Thus, X = {x}.”

A fuzzy set A in x is characterized by a membership function f A(x) which associates with each point in X a real number in the interval [0, 1], with the value of f A(x) at x representing the “grade of membership” of x in A. Thus, the nearer the value of f A(x) to unity, the higher the grade of membership of x in A.”

In a Boolean set, the grades of membership of 0 and 1 correspond to false or true. But membership functions for fuzzy sets can be defined in any number values between 0 and 1. The fuzzy sets are the foundation of fuzzy logic theory. In this theory, different parameters are defined as:

(a) Fuzzy quantifiers

The fuzzy logic introduces between the quantifiers

$\forall {\rm \;\ et\;} \exists $, elements vague corresponding to the general statements of the natural language. There are named fuzzy quantifiers. This quantifier “allow us to express fuzzy quantities or proportions in order to provide an approximate idea of the number of elements of a subset fulfilling a certain condition or the proportion of this number in relation to the total number of possible elements” (Galindo et al., Reference Galindo, Carrasco and Almagro2008).

$\forall {\rm \;\ et\;} \exists $, elements vague corresponding to the general statements of the natural language. There are named fuzzy quantifiers. This quantifier “allow us to express fuzzy quantities or proportions in order to provide an approximate idea of the number of elements of a subset fulfilling a certain condition or the proportion of this number in relation to the total number of possible elements” (Galindo et al., Reference Galindo, Carrasco and Almagro2008).(b) The multivalent or N-ary logic

It is a generalization of the bivalent logic, when the truth-value takes a number n over 2 are elements of the interval unity [0, 1] or for any totally ordered set. We say trivalent logic when n = 3, quaternary logic when n = 4, etc. This is important for our study because we need to have more than two results.

(c) Linguistic variables

Introduced by Zadeh, these variables are not numeric but symbolic (words or linguistic expressions). The notion of variables supposes a reference set U, an X designation of the variable (its name) and a definition domain D X, or a fuzzy set of repository U. A linguistic variable is defined by a triplet (X, U,T x): x designates the name of the variable, U the repository, and T xthe finite set or not of the linguistic values of the X values called terms. The nature of the variable X depends on the nature of the elements of the universe U example: X will denote the age and the universe U designates the set of ages.

(d) Linguistic modifiers

There exists a set of commonly used adverbs which by their action can extenuate or amplify the initial meaning of a number of attributes such as: very, more, at least, slightly. Linguistic modifiers can be considered as operations performed on the membership functions in such a way that the initial values (degrees of membership) are compatible with the modified values, in accordance with the goal of the operation of modification (amplification or mitigation). We suppose that B is a fuzzy feature derived from another fuzzy characteristic A by the modifier m. We write then: b = m(A) or μ B(x) = m(μ A(x)).

(e) Multi- objective decision-making

Often, decisions must be made in an environment where more than one objective affects the problem, and the relative value of each of these objectives is different (Ross, Reference Ross2009). The multi-objective decision problem involves the selection of one alternative, a i, from a universe of alternatives A given a set of criteria or objectives, {O}, that are important to the decision maker.

Define a universe of n alternatives, A = {a 1, a 2, …, a n} , and a set of r objectives, O = {O 1, O 2, …, O r}. Let O i indicates the i objective. Then the degree of membership of alternatives a in O i , denoted ![]() $\mu _{O_i}\; (a)$, is the degree to which alternative a satisfies the criteria specified for this objective. Our objective is to seek a decision function that simultaneously satisfies all of the decision objectives; hence, the decision function, D, is given by the intersection of all the objective sets:

$\mu _{O_i}\; (a)$, is the degree to which alternative a satisfies the criteria specified for this objective. Our objective is to seek a decision function that simultaneously satisfies all of the decision objectives; hence, the decision function, D, is given by the intersection of all the objective sets:

Therefore, the grade of membership that the decision function, D, has for each alternative a, is given by

A set of preferences {P}, which we will constrain to being linear and ordinal are also defined. Elements of this preference set can be linguistic values (low, medium, high, absolute, or perfect); or they could be values on the interval [0, 1]; or they could be values on any other linearly ordered scale, for example, [−1, 1], [1, 10], etc. These preferences will be attached to each of the objectives to quantify the decision maker's feelings about the influence that each objective should have on the chosen alternative.

Let the parameter, b i, be contained on the set of preferences, {B} , where i = 1, 2, … , r . Hence, we have for each objective a measure of how important it is to the decision maker for a given decision.

The decision function, D, now takes on a more general form when each objective is associated with a weight expressing its importance to the decision maker. This function is the intersection of r-tuples, denoted as a decision measure, M(O i, b i), involving objectives and preferences:

Then, we have shown the different definition of fuzzy sets and their application in decision-making representation, we shall see how we may proceed to use the fuzzy theory in our studies.

The application of the fuzzy theory of our model

The advantage of the fuzzy theory is to use the linguistic value and to give for this value a mathematical sense. The main characteristic of this theory is the quantification of the uncertainty. As we know, the human reasoning in different areas is based on uncertainty. These answers completely to our systemic principle for this study. One of our principal preoccupations is how to interpret the impact of the stress in crisis situations using the human behavior and reasoning. The preferred method is to use natural language. This is most comprehensive and simplest to interpret it. Our proposition is so to use the natural expression or words with fuzzy theory and especially the fuzzy sets.

Components of the model

As previously announced, the crisis situation can be represented by several states evolving through time and space. A state can generate events and events can modify states and so on. For the next phase of this study, we are going to give more precision about some components that will enable us to use this theory.

We define for the first time a number of the sets:

• A is a universe of three actions:

(1)where a 1 = Communication; a 2 = Coordination; and a3 = Cooperations.. $$A = \lcub {a_1\comma \,\; a_2\comma \,a_3} \rcub \; $$

$$A = \lcub {a_1\comma \,\; a_2\comma \,a_3} \rcub \; $$• B is a universe of n actors:

(2) $$B = \lcub {b_1\comma \,\; b_2\comma \, \ldots\comma \, b_n} \rcub $$

$$B = \lcub {b_1\comma \,\; b_2\comma \, \ldots\comma \, b_n} \rcub $$• C is a universe of r places:

(3) $$C = \lcub {c_1\comma \,\; c_2\comma \, \ldots\comma \, c_r} \rcub \; $$

$$C = \lcub {c_1\comma \,\; c_2\comma \, \ldots\comma \, c_r} \rcub \; $$• D is a universe of j data:

(4) $$D = \lcub {d_1\comma \,\; d_2\comma \, \ldots\comma \, d_j} \rcub \; $$

$$D = \lcub {d_1\comma \,\; d_2\comma \, \ldots\comma \, d_j} \rcub \; $$

D includes different kinds of information such as weather (w); crisis-place (cp); victims (v); population (p); morphology-of-land (m); assailant (as): infrastructure (in); and crisis-situation (cs). Then the function D is represented as the intersection of r-tuples noted:

• F is the universe of q means:

(6) $$F = \lcub {\,f_1\comma \,\; f_2\comma \, \ldots\comma \, f_q} \rcub \; $$

$$F = \lcub {\,f_1\comma \,\; f_2\comma \, \ldots\comma \, f_q} \rcub \; $$• T the set of I time:

(7)The linguistic variables is a set of atomic terms defined and in relation to the own experience of the expert. $$T = \lcub {t_1\comma \,\; t_2\comma \, \ldots\comma \, t_i} \rcub \; $$(8)

$$T = \lcub {t_1\comma \,\; t_2\comma \, \ldots\comma \, t_i} \rcub \; $$(8) $$G = \lcub {{\rm aqual}\comma \,\; \,{\rm increase}\comma \,\; \,{\rm decrease}\comma \,\; \,{\rm probably}} \rcub $$

$$G = \lcub {{\rm aqual}\comma \,\; \,{\rm increase}\comma \,\; \,{\rm decrease}\comma \,\; \,{\rm probably}} \rcub $$

A State is defined as a function composed by actors (b), place (c), means (f), and data (d):

The function event is composed of the couple action (1) or data (4), and by actors (2).

for all a ∈ {a 1, a 2, a 3}. State and event attributes are detailed in the following.

The objective is defined as impact-stress function composed by the functions state (9), events (10), and the sets of the time (7) and the linguistic modifier (8).

The prediction of the state is the union of decisions at each time.

Actors/sources

In the situation of crisis, different categories of actors are concerned and implicated in the management of this situation. They represent different organizations (Government, police, army, medical emergency, firefighters, Rescuers associations, etc.). They have different way of management; hierarchical and/or balanced one. Decision-making can be done at three levels: strategic, tactic, and operational. For clarity reason, we represent two role types of actors at each level: responsible and subordinate (Fig. 11). In addition to that, the population who are involved in the situation is also taken into account. This population can influence crisis management.

Fig. 11. the internal component and hierarchical organization of the crisis management.

Place

For these studies, it defined four different places: the crisis place; the evacuation places; the command post; and the operation post.

Means

In the crisis situation, different actors can use different means. For simplicity, this study defined four kinds of means: for transmission; for transport; for medical emergency, and for safety.

Data

This is the most important component. It can influence the management of the crisis. It can be the source of the stress and may impact the future of the situation. There is a large amount of data, for us, we defined the most pertinent and for each of them, we defined certain qualifications. Of course, this list is not limited.

– Weather: rain; snow; sun; fog; heat; cold; etc.

– Victims: dead; injured; serious injured; slight injured; etc.

– Population: disappeared; threatening; survivors; helping; hostile; etc.

– Morphology of the land: lowland, mountain, wooded, nude, hill.

– Assailant: terrorist, criminals, hooligans, breakers; etc.

– Situation of crisis: long period, short period, medium period, degenerate, reduce; etc.

– Infrastructure: roads, bridges, houses, railroads, transmission relay.

– Places of crisis: limited areas, unlimited areas. another place, same place.

Action

In our study, we consider only actions as the consequence of the stress impact. It is composed of three components: Communication; Cooperation; and Coordination.

– Communication: Silence; Speak quickly; Speak slowly; Repeat words; Aggression; Speak normally.

– Coordination: Aggression; Inappropriate; Intense activity; Single-action fixation; Repeat actions; Delegate actions; Organize actions.

– Cooperation: Simplification of the situation; Imposing a decision; No decision; Conflict; Collective decision.

In addition to these components and inspired by the fuzzy theory, we added some linguistic modifiers. These give a sense to the linguistic variables by reducing or amplifying state attributes.

Linguistic modifiers

We defined some of them: increase, decrease, probable, change, equal, same, and probably.

The stress-impact function

Experience feedback is used in order to identify the stress-impact function using linguistic converters, as noted above:

Stress-impact definition using experience feedback

The crisis management expert is interviewed in order to represent the consequences of each Triple C action on state attributes. These consequences considered mainly stress impact actions as noted above.

For the Communication action

For the Coordination action

For the Cooperation action

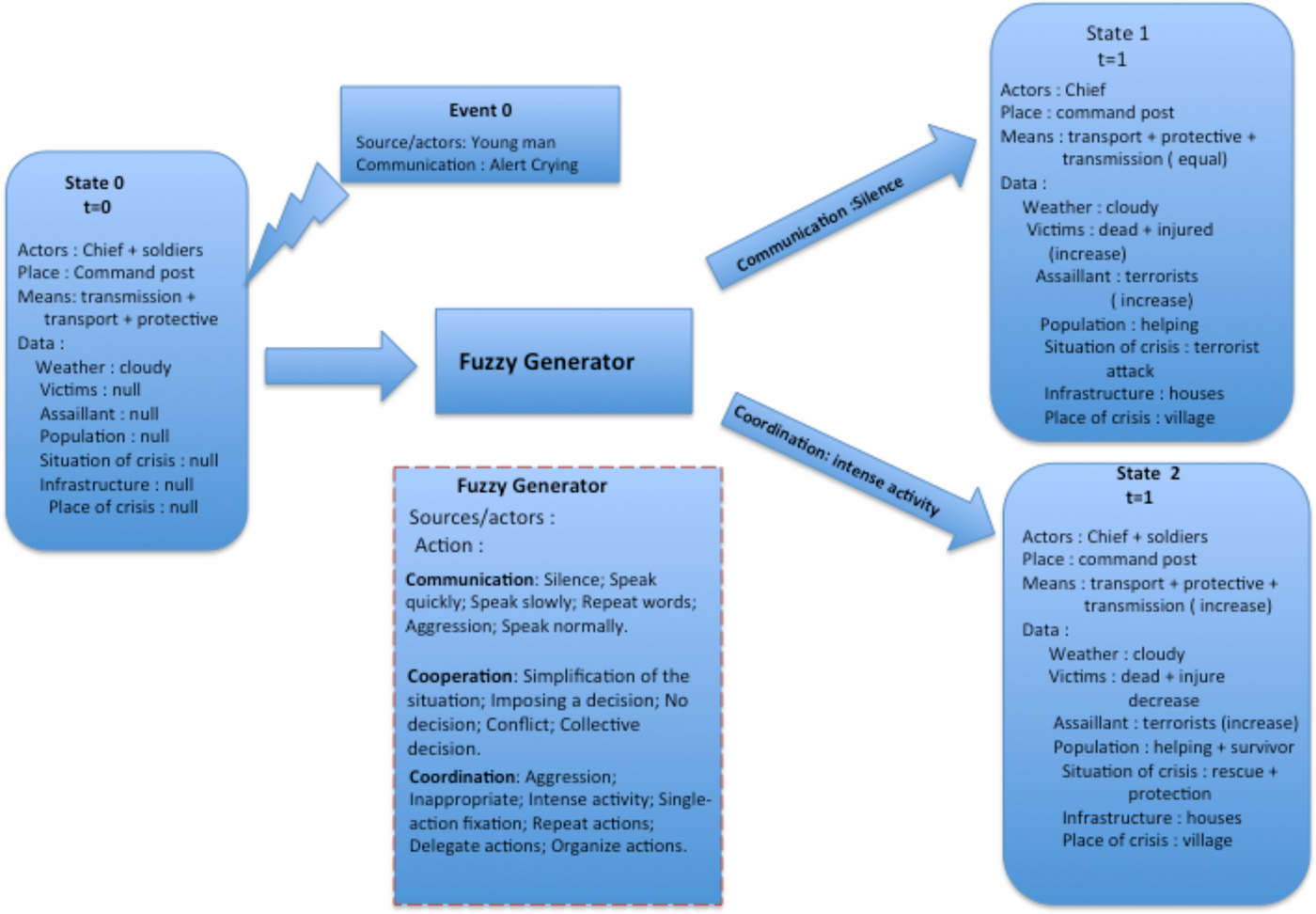

Given an event (action/data, source), event 1, and having a state, State-1, The State Generator process applies stress-impact function related to each Triple C action, using linguistic modifiers as defined by experience feedback tables. Several states can be so generated (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. The process used for generating situation.

Example of generation

To show the contribution of the state generator process, we will present for the first time, a situation with the impact of the stress (Fig. 13). It is the same as the model studied above (red state, Fig. 10). After that, we use the generator (called fuzzy generators). The scenario begins when the young man came and alerted the soldiers.

Fig. 13. The process used without fuzzy generators.

In this model, we have more detail than the previous model. Also, we can observe how some data such as victims, place, and assailants using the linguistic converters can change. These permit to the manager to have the best understanding of the situation and to take the best decision in managing the crisis situation.

Applied the fuzzy generator on the same example, we can also note that for the same state and for the same action, cooperation, the fuzzy generator can generate a variety of situations (Figs. 14–16). Otherwise, for the same state we can use other actions and with the fuzzy generator, we can generate a considerable number of states.

Fig. 14. The fuzzy generator with the same action.

Fig. 15. The fuzzy generator and with but different action (same C).

Fig. 16. The fuzzy generator with different actions (different C).

Conclusion

The current study determines the stress impact including the experience feedback in the situation of the crisis management. It suggests a stress impact predict situations, which generate a number of very useful states for crisis management training actors. Based on that, we answer the main question about the possibility to represent stress impact in crisis management and by using experience feedback in order to show consequences of stress behavior. Experience feedback is also used in our system to show actions to avoid stress consequences. Actions are defined under three dimensions: cooperation, coordination, and communication-related to the representation of collaborative crisis management activity. This representation is illustrated in a real case study in order to verify its applicability. The situations predict system is based on the Fuzzy set theory that helps to deal with uncertainty and dynamicity of situations. Therefore, for the same state and for the same action, the predict system can generate a variety of situations. A natural progression of this study is to develop the algorithm of the stress impact prediction in order to test in other crisis cases. This type of environment can be used for training. This can help them to confront different situations of the crisis management in an efficient manner.

Author ORCIDs

Sammy Teffali, 0000-0002-6410-2562

Sammy Teffali is a PhD student in computer science at the University of Technology of Troyes (France). His research revolves mostly around the feedback experience, the stress impacts, the knowledge management, the fuzzy theory, and crisis management. He holds a Master of Science from the University of Technology of Troyes. Prior to starting his doctorate, he served in the Algerian Army for 30 years. He participated in the war against terrorism in his country. And now, his aim is to contribute to the improvement of the management of crisis through his experience.

Nada Matta is a Full Professor at the University of Technology of Troyes. She has studied techniques in knowledge engineering and management and specially to handle cooperative activities such as product design, crisis management, etc. Currently, she is Director of department of “Human, Environment and ICT”. She had assumed several responsibilities such as Director of “Scientific group of supervision, and security of complex systems” for 5 years and Director of department of “Information Systems and Telecom” for 2 years. She had involved in the organization of several workshops and tutorials on IJCAI, KMIS, ISCRAM, ECAI, COOP, CTS conferences. She had written several books on KM in companies and learning. She had involved in scientific committee of several conferences, journals, and research groups and managed several projects on the application of KM in several domains (design, consulting, security, and safety). She had completed her PhD in knowledge engineering and Artificial Intelligence at the University of Paul Sabatier in collaboration with ARTEMIS. She had worked at INRIA for 4 years in projects with Dassault-Aviation and Airbus Industry (http://matta.tech-cico.fr/en).

Eric Chatelet has been Professor at the University of Technology of Troyes (UTT, France) from 1999. He received his PhD (1991) in Theoretical Physics (Cosmic rays physics) from Bordeaux I University, France. He was the Director of studies of the UTT (2001–2004) and the Director of academic programs (2005–2006), and co-manager (2006–2007) of the national program of the National Agency of the Research in Global Security. He was vice-director (2009–2013) of the Charles Delaunay Institute (ICD) and he has been the head of the “Sciences and Technologies for Risk Management” team from 2010. His research is focused on stochastic modeling and optimization for maintenance and reliability, the performance analysis (risk) of complex systems and security/vulnerability analysis. He is member of the IMdR (French institute of risk management), of ESRA (European Safety and Reliability Association), and of the Scientific Council of the CSFRS (High Council for Strategic Research and Education, 2010–).