Introduction

In the design process, problem statements are both inputs and stimulus to designers’ internal minds, and they can guide, constrain, and even determine designers’ cognitive behaviors (Zhang, Reference Zhang1997). The first stage in the product design process is defining a design problem. Different types of problem statements have different influences on designers’ cognitive behaviors (status) and resulting in different strategies to solve the problem. In this study, we suggest that the different problem statements can manipulate the internal representation and then discuss how the problem statements impact the designer's cognitive behaviors (status) and performance in the design process. This research will help designers understand the design problem-solving process from the perspective of cognitive science, and it will provide a set of strategies that can be used to improve designers’ ideation approaches and outcomes. Furthermore, it would be helpful for training designers. The different problem statements could be used to hone the different skill sets associated with solving the distinct problem types.

Problem statements are defined as the knowledge and structure in the problem stem, as symbols, rules, constraints, or relations embedded in physical configurations. The information in problem statements can be picked up, analyzed, and processed by perceptual systems alone. In contrast, internal representations are the knowledge and structure in memory, as propositions, productions, schemas, neural networks, or in other forms. The information in internal representations has to be retrieved from memory by cognitive processes, and the cues in problem statements can sometimes trigger the retrieval processes (Zhang, Reference Zhang1997). The way a problem is structured and perceived by designers impacts the resulting outcomes, whether the context is education, research, or the workplace (Ryd, Reference Ryd2004). The wording of a problem statement can enhance or limit whether individuals with diverse expertise see their varied experiences and knowledge as relevant (Spradlin, Reference Spradlin2012). Silk et al. (Reference Silk, Daly, Jablokow, Yilmaz and Rosenberg2014) demonstrated that the structure of design problem statements influences an individual's approach and the outcomes produced. Psychological studies of the problem statements effect on problem solving have focused on a few well-structured problems, including the Tower of Hanoi problem (Kotovsky et al., Reference Kotovsky, Hayes and Simon1985), visuospatial analogical reasoning task (Geake &Hansen, Reference Geake and Hansen2010; Watson & Chatterjee, Reference Watson and Chatterjee2012), and Chinese Ring Puzzle (Megalakaki et al., Reference Megalakaki, Tijus, Baiche and Poitrenaud2012). These studies found that different problem statements can have an impact on problem difficulties even if the formal structures are the same. In the problem-solving process, different computing capability and memory workloads are required and the time spent on them is different as well. As the case stands, Tower of Hanoi problem and visuospatial analogical reasoning task are mostly simple cognitive tasks. Compared with the design task, there is still more work to be done (Dietrich & Kanso, Reference Dietrich and Kanso2010). The design problem is typically an ill-defined problem, which differs from a logical reasoning problem (Cross, Reference Cross2008). Word choices, relevant information, and stated goals within these design problem statements are likely to impact the approaches to generating solutions, as well as the design solutions themselves. Thus, as we seek to improve design skills and outcomes, we need to understand how the design problem statements can influence the designer's cognitive behaviors.

There is no common classification of design problem statements. Researchers have shown that design problems can be classified in accordance with an assessment of knowledge or how complete is the available knowledge in solving design problems (Jin & Chusilp, Reference Jin and Chusilp2006). Gero (Reference Gero1990) classified design problem into a creative, innovative, and routine design. Jin and Chusilp (Reference Jin and Chusilp2006) defined a creative/routine design and a constrained/non-constrained design. Design problems are usually open-ended (Cross, Reference Cross2002), and the designers use different strategies or approaches to search the design space for potential ideas to consider. But each design problem includes some bounds and constraints that help clarify the problem. Designers ultimately select (and implement) the one idea that they believe will effectively solve the design problem. In order to study the influences of different design problem statements on problem-solving, the statement types of design problem are divided into open-ended (OE), decision-making (DM), and constrained (CO) statements in this study. The OE statement implies that there is less constraint to a design problem and the solutions have no corresponding evaluation standard, while CO statement refers to relatively more constraints to a design problem. The DM statement refers to the problem stem presenting several solutions for problem solvers to choose.

Product design process is an iterative, repeated divergent, and convergent process with the number of solutions gradually decreased. Creative problem-solving is the combined effect of various cognitive behaviors. The Dual Pathway to Creativity Model that was put forward by De Dreu et al. (Reference De Dreu, Baas and Nijstad2008) argued that a design problem can be solved through both flexible and associative cognitive control, and deliberate, effort-conscious analysis. Conceptual design should contain two kinds of steps: divergent in which alternative concepts are generated, and convergent in which these are evaluated and selected (Liu et al, Reference Liu, Chakrabarti and Bligh2003). Divergent thinking (the ability to generate ideas by comparing and combining disparate forms of information in novel ways; Guilford, Reference Guilford1967) helps designers expand their search space in order to consider multiple and diverse alternative ideas. In Fink et al. (Reference Fink, Grabner, Gebauer, Reishofer, Koschutnig and Ebner2010) and Chrysikou et al. (Reference Chrysikou and Thompson Schill2011), alternative use tasks are used to study divergent thinking in the problem-solving process, and it is pointed out that divergent thinking ability is significantly related to the emergence of novel solutions. Lee and Therriault (Reference Lee and Therriault2013) recruited 265 participants to complete a battery of tasks and explored the effects of divergent thinking on work memory based on structural equation models. They found that divergent thinking affects working memory capacity, thus affecting ideational fluency and flexibility in the problem-solving process. There are also studies holding that the design problem-solving process is about integrating existing information and reasoning through convergent thinking (i.e., logically building associations and linearly moving toward the conclusion; Lee and Therriault, Reference Lee and Therriault2013). Kijkuit and Ende (Reference Kijkuit and Ende2007) explored the influences of convergent thinking on creative problem-solving through controlling the amount of interference information in DM problems. The results show that the less the interference information is, the stronger the participants’ convergent thinking is, and the higher their efficiency of solving problems is. Additionally, some researchers pointed out that in the product design process, creativity is related to mental workload (the demands imposed by tasks on the operator's limited information-processing resources; Wickens, Reference Wickens2008), and the creativity at moderate stress level is higher than that at low and medium stress levels (Nguyen & Zeng, Reference Nguyen and Zeng2014). The above research explored the impact of divergent thinking, convergent thinking, and mental workload on creative problem-solving from the perspective of cognitive behaviors.

At present, there are some studies on the impact of cognitive behavior on the problem-solving, but rarely focus on the impact of problem statements on designer's cognitive behavior, thus resulting in different outcomes. Electroencephalography (EEG) was proved to be an effective tool for quantitative analysis in the investigation of cognitive processing reflection on functional cerebral organization (Basar et al., Reference Başar, Başar-Eroğlu, Karakaş and Schürmann1999). In this study, we used EEG to analyze the brainwave patterns of cognitive behaviors (divergent thinking, convergent thinking, and mental workload) of designers and explore the differences resulting from three different problem statements (OE, DM, and CO) in the product design problem-solving process. In this research, four hypotheses are proposed: (1) designers in different problem statements will show different patterns of brain activity during the phase of idea generation; (2) the OE statement is more conducive to problem solvers’ divergent thinking, so as to get more innovative solutions; (3) both DM and CO statements are more propitious to convergent thinking, and the solutions to such problems are more feasible; (4) the DM statement can reduce problem solvers’ mental workload, which is helpful for solving problems effectively.

Background: EEG and divergent thinking, convergent thinking, and mental workload

EEG is brain neurons’ idiopathic and rhythmic electrical activity recorded through electrodes. EEG is the most sensitive to changes to cortical activation (Gevins & Smith, Reference Gevins and Smith2006). Based on frequency, EEG behavior can be divided into δ (0.5–3.5 Hz), θ (4–7 Hz), α (8–12 Hz), and β (14–25 Hz). The changes of EEG signals in different frequency bands reflect different cognitive activities (Basar et al., Reference Başar, Başar-Eroğlu, Karakaş and Schürmann1999). Based on EEG technology, the studies on divergent thinking, convergent thinking, and mental workload are focused on the following aspects:

(1) Divergent thinking refers to the ability to generate ideas by comparing and combining disparate forms of information in novel ways (Guilford, Reference Guilford1967). Changes to α in control tasks are indeed often observed when participants work in divergent thinking tests (Dietrich & Kanso, Reference Dietrich and Kanso2010). The α band is prominent when a person is awake but relaxed. In early studies, Martindale and Hines (Reference Martindale and Hines1975; Martindale, Reference Martindale and Sternberg1999) demonstrated that EEG α waves were related to high creative activity while performing divergent tests. Arden et al. (Reference Arden, Chavez, Grazioplene and Jung2010) demonstrated that either amplitude (power) or synchronization changes in the α band associated with creative task performance. Razumnikova (Reference Razumnikova2007a, Reference Razumnikovab) analyzed spectral power during divergent thinking tests and thought that the upper α powers were significantly higher during the cognitive tasks than that during the rest periods. Some investigators have reported the frontal α increases in synchrony associated with divergent thinking (Fink et al., Reference Fink, Grabner, Benedek and Neubauer2006; Fink et al., Reference Fink, Grabner, Gebauer, Reishofer, Koschutnig and Ebner2009a, Reference Fink, Graif and Neubauerb; Grabner et al., Reference Grabner, Fink and Neubauer2007), and the α at the temporal or parietal sites showed decreases with the originality score (Razumnikova et al., Reference Razumnikova, Volf and Tarasova2009). Furthermore, Klimesch suggested that the inhibition and timing of the α-band oscillations were closely linked to access the knowledge and the encoding of new information arising (Klimesch, Reference Klimesch2012). Different responses of the α band at different brain regions may reflect different neurocognitive processes. Increases in EEG α power during creative ideation are among the most consistent findings in the neuroscientific study of divergent thinking (Schwab et al., Reference Schwab, Benedek, Papousek, Weiss and Fink2014). We hence can conclude that increased levels of α power are specifically related to the process of divergent thinking.

(2) Convergent thinking refers to a directional structured way of thinking that looks for a well-established answer to a problem (Arthur Cropley, 2006). It reflects the ability of a designer who explores the solutions to different problems depending on allocating cognitive attention positively. Razoumnikova (Reference Razoumnikova2000) demonstrated that convergent thinking-induced coherence increases in the caudal regions of the cortex in the θ band. Mölle et al. (Reference Mölle, Marshall, Wolf, Fehm and Born2010) found that power in the θ band increased over frontal recordings during convergent thinking in comparison with divergent thinking. In his previous work (Mölle et al., Reference Mölle, Marshall, Lutzenberger, Pietrowsky, Fehm and Born1996), a higher level of power in the α frequency band of the EEG, which is a common marker for a general decrease in cortical arousal, was found during divergent thinking as compared with convergent thinking. Jauk et al. (Reference Jauk, Benedek and Neubauer2012) thought that convergent thinking induced lower task-related α power than divergent thinking. The study above suggests the reduction of α activity and the increase of θ activity in convergent thinking.

(3) Mental workload can be defined as the total use of cognitive resources. It is a standard practice to assess mental workload during system design and evaluation in order to avoid operator overloading in a variety of industrial, transportation, military, and medical contexts. Mental workload investment has been described as energy mobilization in the service of cognitive goals. The most simple and commonly used EEG workload indices are measures of spectral power density in conventional frequency bands (Borghini et al., Reference Borghini, Vecchiato, Toppi, Astolfi, Maglione, Isabella, Caltagirone, Kong, Wei, Zhou, Polidori, Vitiello and Babiloni2012). Researchers focused on the changes of EEG signal in the tasks at different levels of task complexity, and put forward that the demand of mental workload increased with the complexity of cognitive task, under the assumption that a high cognitive task usually requires additional cognitive resources. While in this case, β activity decreased and α and θ activities increased. Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Blanco, Gentili and Jaquess2015) developed probe-independent algorithms for classifying three levels of mental workload based on four-channel EEG recordings during simulated flight. Trejo et al. (Reference Trejo, Kubitz, Rosipal, Kochavi and Montgomery2015) constructed a practical system that can use EEG features to estimate the instantaneous degree of mental fatigue, and they thought that mental fatigue was associated with increased power in frontal θ and parietal α EEG rhythms. An increase of activity in the α and θ bands predominantly in the parietal and central regions of the brain is generally observed when the participant is fatigued or tired, in association with a decrease in higher frequency bands (Lal & Craig, Reference Lal and Craig2002; Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Shigihara, Ishii, Funakura, Kanai and Watanabe2012).

In this paper, EEG equipment was used to collect designers’ brain activities when they were in the process of solving creative problems with different statements’ tasks. Through the analysis of EEG signals, the designer's divergent thinking, convergent thinking, and mental workload were recorded and evaluated. Thus, the influences of different problem statements on the creative problem-solving can be quantified. The above outside studies suggested that divergent thinking (D) was positively correlated with the α band. Convergent thinking (C) was positively correlated with the θ band and was negatively correlated with the α band. The mental workload (W) was negatively correlated with the sum of α and θ bands, and positively correlated with the β band.

where D is the evaluation of divergent thinking, C is the evaluation of convergent thinking, W is the evaluation of mental workload, and α, β, and θ respectively refer to the power spectral density (PSD) of α, β, and θ bands.

Methods

Participants

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of Sichuan University. Nineteen graduate students (aged 22–26 years, 13 males, mean age of 23.6 years) participated voluntarily in this experiment. These participants had no history of medical, psychiatric, or neurological disorders or treatment that could have interfered with any of the behavioral and neurophysiologic measures. All the participants were first-year graduate students from the School of Manufacturing Science and Engineering of Sichuan University. We assumed that all participants were at the same levels of creativity and experience. Each participant was compensated with a gift card.

Experimental tasks

There are three design problems (winter railway, coin sorting, and bedroom decoration), and for each, three tasks are created. Each task is with one of the statement types, OE, DM or CO statement. There are nine design tasks as shown in Table 1. We ensured that each participant took three tasks with different statements from different design problem domains. We tried to control problem domain variables in the analyses in this manner. For example, three design tasks carried out by participant 1 were design problem 1 with OE statement, design problem 2 with CO statement, and design problem 3 with DM statement. We assumed that the relationship between problem statements and cognitive behavior was independent of the design task. Design problems 1 and 2 are engineering design problems, and design problem 3 is an interior design problem. The advantages of this experiment setting are that its topic covers a wide range and it reflects the real design process.

Table 1. Design problems used in the experiment

Experiment procedures

Each of the experimental tasks was cycled in this study, and each cycle had four steps, as shown in Figure 1. All tasks started with the presentation of a fixation cross for a time period of 20 s; the EEG signals were recorded as references for the following data analysis. Subsequently, the question stems were presented on a computer screen for 60 s. After that, it was to be an idea generation stage. Participants needed to get an idea based on the question stem limited to 3 min. In the response stage, participants expounded on their ideas by oral description and supplemented by sketches. They just provided one solution in each trial. After expounding they entered the next circulation. Throughout the experiment, we mainly record and analyze the EEG data in the idea generation stage. The EEG data in the response stage are not included.

Fig. 1. Experiment procedures.

The EEG was measured (BrainProduct actiChamp-32) by means of electrodes located in an electrode cap in 33 positions (according to the international 10–20 system with interspaced positions); a ground electrode was located on the forehead, and the reference electrode was TP9. Electrode impedances were kept below 5 kΩ for the EEG. All signals were sampled at a frequency of 50 KHz. The electrode position distribution and experimental scene are shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Electrode positions (left) and experiment scene (right).

EEG data analysis

The raw EEG signals were analyzed by means of the software BrainVision Analyzer (BrainProducts.). Brain activity during the performance of experimental tasks was quantified by means of task-related power (TRP) changes in the EEG (Pfurtscheller & Fh, Reference Pfurtscheller and Fh1999). TRP at an electrode i was obtained by subtracting (log-transformed) power during a pre-stimulus reference interval (Powi reference) from (log-transformed) power during the activation interval (Powi activation) according to the formula: TRP(log Powi) = log [Powi activation] − log [Powi reference]. All the operations were executed via the software BrainVision Analyzer 2.1, such as band pass filter, PSD. The data processing procedure is shown in Figure 3. First, EEG data were captured and collected through the BrainProduct actiChamp-32 from the participants while they were carrying out the design tasks; and then with the principal component analysis, the EEG data were cleaned from the noise signals, and the collected EEG records were band-pass filtered between 0.1 and 40 Hz to eliminate artifacts related to higher frequencies. Finally, fast Fourier transform was used to calculate the spectral power in the EEG rhythms of δ, θ, α, and β.

Fig. 3. Flowchart of data processing procedures.

In order to further analyze the effects of different problem statements on different regions of the brain, electrode positions were aggregated as following: frontal left (FP1, FC9, F3, F7), frontal right (FP2, FC10, F4, F8), frontocentral left (FC1, FC5), frontocentral right (FC2, FC6), centrotemporal left (C3, T7), centrotemporal right (C4, T8), centroparietal left (CP1, CP5), centroparietal right (CP2, CP6), parietotemporal left (P3, P6), parietotemporal right (P4, P8), occipital left (O1), and occipital right (O2). The midline electrodes (FZ, CZ, PZ, and OZ) were not included in the analyses (as we were also interested in potential hemispheric differences).

Results

Behavior results

Recent research has suggested that conventionality, in addition to novelty, creates value for invention (Uzzi et al., Reference Uzzi, Mukherjee, Stringer and Jones2013). Three experts (experienced designers) were instructed to evaluate each solution and the data of protocol analysis from the novelty and the conventionality on a rating scale ranging from 0 (the lowest novelty and conventionality) to 10 (the highest novelty and conventionality). In the OE and CO task, rating novelty included the assessment on the originality of solution and the psychological creativity of participants (designers) themselves. Rating conventionality included the assessment on the feasibility of solution and the fluency of designers’ thinking. In the DM task, solutions are selected from a predefined list, so the novelty is measured by assessing the psychological creativity of participants and the conventionality is measured by assessing the fluency of thinking. The assessment of the originality and feasibility of the solution is based on the sketches, and the assessment of the psychological creativity and the fluency of thinking is based on the retrospective protocol. Psychologically creativity refers to the creative thinking in the problem-solving process. For example, participant 1 said “I like this room layout. And in this room, maybe I can hear a bird sing”. So we evaluated that participant 1 had a good performance in psychological creativity. Participant 2 said “I saw this solution before. I think it is feasible”. We evaluated that participant 2 had a bad performance in psychological creativity. In addition, in order to analyze participants mental workload, we recorded the time interval (second) of the idea generation phase. Table 2 shows the average score of all participants in the three design tasks. The interrater correlations (with Kendall'W) for the novelty score (w = 0.657, P < 0.05) and the conventionality score (w = 0.732, P < 0.05) have satisfactory interrater reliability.

Table 2. Average score of all participants in the three design tasks

In order to test potential group differences during the performance of design tasks, we computed analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures (separately for the novelty, conventionality, and time spent) using TASK (OE, DM, and CO) as participant variables, as shown in Table 3. The results of novelty evaluation indicated that the average score of novelty of ideas in the OE task [M = 7.80 (SD = 0.50)] was higher than that in the DM [M = 7.30 (SD = 0.70)] and CO tasks [M = 7.25 (SD = 0.80); F(2,54) = 3.96, P = 0.025 < 0.05]. According to the least significant difference (LSD) multiple comparative analysis, the average score of novelty showed a significant difference when comparing the OE task with CO task (P < 0.05) and comparing the OE task with DM task. There is no significant difference between the CO and DM task. The result of conventionality evaluation indicated that the average score of conventionality of ideas in the CO task [M = 7.61 (SD = 0.71)] was higher than that in the OE [M = 7.03 (SD = 0.57)] and DM tasks [M = 7.24 (SD = 0.59); F(2,54) = 4.143, P = 0.021 < 0.05]. The average score of conventionality showed a significant difference when comparing the OE with CO tasks, and there is no significant difference between the CO and DM tasks, and between the OE and DM tasks. The result of time measurement indicated that the time spent on the idea generation phase in the DM task [M = 19.11 (SD = 4.16)] was far less than that in the OE [M = 101.26 (SD = 14.56)] and CO tasks [M = 98.84 (SD = 11.39); F(2,54) = 346.914, P ≤ 0.01]. This is because that the problems were at different levels of difficulty. Solving DM problem is much easier than solving OE and CO problems. According to LSD, there is a significant difference in the time spent between the OE and DM tasks, and between the CO and DM tasks, and there is no significant difference when comparing the OE with CO tasks. In summary, the OE statement is more conducive to the novelty of the solution in the creative problem-solving process; the CO statement is helpful for generating more practical solutions and participants spend the least time on the DM statement.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and ANOVA results of the novelty, conventionality, and time (s) of various problem statements

PSD topographic distribution

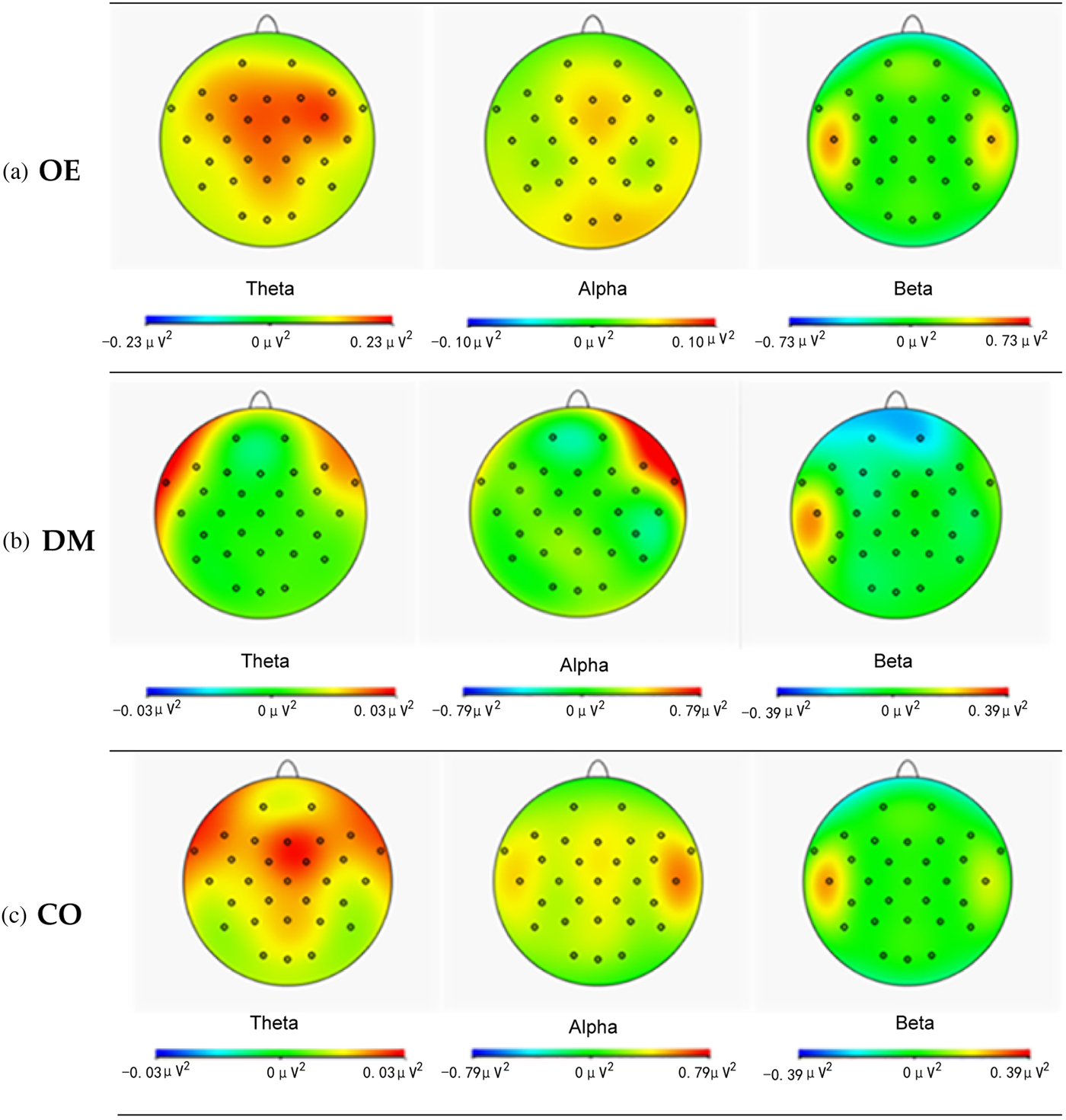

With the image data, we compared the brain activation regions of the design tasks with three different statements to study brainwave patterns of cognitive behaviors in the creative problem-solving process. Figure 4 shows the PSD topographic distribution of θ-, α-, and β-band activity for three problem statement tasks. Activities in the red region are stronger than that in other regions.

Fig. 4. PSD topographic distribution of the θ-, α-, and β-band activity in different statement tasks. (a) The open-ended task; (b) the decision-making task; (c) the constrained task.

As shown in Figure 4, θ activity is mainly activated in the frontal and parietal regions in the OE and CO tasks. Besides, the θ power in the CO task is greater than that in the OE task. But in the DM task, θ is not activated in any region. Brookings et al. (Reference Brookings, Wilson and Swain1996) argued that θ activity is usually enhanced in the task that requires sustained attention. It is well documented that an increase in θ power is functionally related to increased demands of working memory and attention expectation, which also has been interpreted as expressing top–down control processes (Sauseng et al., Reference Sauseng, Griesmayr, Freunberger and Klimesch2010). The results show that the subjects are more focused on the CO task, which means that sustained attention is needed and more cognitive resources are taken up when solving such problems.

The α activity is enhanced in the posterior (i.e., parietal, temporal, occipital) brain region in the OE task and in the center (i.e., parietal, temporal) brain region in the CO task. But in the DM task, the α activity is suppressed in the frontal and temporal regions. In contrast to the differences between the left and right hemispheres in the OE task, the α power in the right hemisphere is greater than that in the left hemisphere. It shows that α activity in the temporal and occipital regions in the right hemisphere is strengthened in the OE task. Fink et al. (Reference Fink, Grabner, Benedek, Reishofer, Hauswirth, Fally and Neubauer2009a, Reference Fink, Graif and Neubauerb, Reference Fink, Schwab and Papousek2011) found that the α activity is activated in the right temporal and right occipital regions during the creative task. There appears to be a robust evidence that EEG α power is particularly sensitive to various creativity-related demands involved in creative ideation (Fink & Benedek, Reference Fink and Benedek2014). The α power varies as a function of creativity-related task demands and the originality of ideas is positively related to an individual's creativity level, and has been observed to increase as a result of creativity interventions. Experimental results show that the α activity is related to divergent thinking; the performance in divergent thinking in the OE task is better than that in the DM and CO tasks.

The β activity is enhanced in the temporal region in all three tasks, but its power is the highest in the CO task and the lowest in the DM task. Gola et al. (Reference Gola, Magnuski, Szumska and Wróbel2013) put forward that the β activity mainly reflects attention and alertness. In the DM tasks, the problem stem contains all the information involved in the problem-solving process. The solution of the DM problem is the integration and reorganization of existing information in the problem stem, and it rarely involves divergent thinking.

Data analysis and discussion

Statistical analysis of EEG data was performed by the analysis of covariance method, with novelty and conventionality scores as the covariates. We discussed the influence of TASK (OE, CO, and DM statements) to COGNITIVE BEHAVIOR (divergent thinking, convergent thinking, and mental workload), HEMISPHERE (left vs. right hemisphere), and AREA (F – frontal, FC – frontocentral, CT – centrotemporal, CP – centroparietal, PT – parietotemporal, O – occipital).

Divergent thinking

Figure 5 shows the average quantitative results of the participants’ divergent thinking (D) in the tasks of different problem statements. The analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) showed that different tasks had obviously different effects on divergent thinking ability [F (2304) = 41.353, P < 0.01]. In the centrotemporal, centroparietal, parietotemporal, and occipital regions, the D value for divergent thinking is the largest under the OE tasks, and is the smallest under the DM ones. It can be seen that the OE statement has the greatest influence on the divergent thinking, and the DM statement has the least influence. There are fewer constraints in the OE statement than that in the other statements. Zabelina et al. (Reference Zabelina, Saporta and Beeman2016) demonstrated that divergent thinking and creative achievement were weakly related, but divergent thinking was associated with flexible attention. Constraints of the design problem could fix the designers’ attention. Yilmaz and Gonzalez (Reference Yilmaz and Gonzalez2010) argued that external information might aid the cognitive process within the design domain while hindering the information processing between domains. The results suggest that constraints may put the designer in a focused state, thus weakening divergent thinking.

Fig. 5. Task-related power (TRP) of divergent thinking (D) during the performance of the OE, CO, and DM tasks separately for the left and the right hemispheres. F, frontal; FC, frontocentral; CT, centrotemporal; CP, centroparietal; PT, parietotemporal; O, occipital.

In the OE task, the right hemisphere displayed a higher D value than that in the left one, as it was evident by an interaction HEMISPHERE and TASK [F(2304) = 4.782, P = 0.009 < 0.01]. Metusalem et al. (Reference Metusalem, Kutas, Urbach and Elman2016) and Bowden and Jung-Beeman (Reference Bowden and Jung-Beeman2003) have put forward that creative thinking is related to cognitive functions in the right hemisphere. The activities in the right-hemisphere regions are associated with fuzzy semantic processing, such as activating the fuzzy meaning of the words and building more remote connections. The above function spectrum analysis also presented this issue.

In addition, there were significant differences between brain regions and divergent thinking [F(5304) = 171.739, P < 0.01]. As shown in Figure 5, the D value for divergent thinking is apparently higher in the frontal, temporal, and occipital regions. Multiple comparisons (Bonferroni) were performed on the brain region factor. The result of multiple comparisons of the D value in different regions shows that the D value in the frontal, parietotemporal, and occipital regions is higher than that in other regions (P < 0.05). These findings could be explained by the role of these cortical lobes in semantic memory search and retrieval (Fink et al., Reference Fink, Grabner, Benedek and Neubauer2006; Razumnikova et al., Reference Razumnikova, Volf and Tarasova2009). Green et al. (Reference Green, Kraemer, Fugelsang, Gray and Dunbar2010) studied the brain mechanism of creative problem-solving by fMRI and it indicated that middle temporal gyrus and middle frontal gyrus may be involved in cognitive functions of spatial search, then participants would put more attention resources on the remote association, and then form a novel solution. The behavior results showed that the OE task had the greatest influence on novelty. The novelty score as a covariate has a significant effect on the D value [F(1, 304) = 3.938, P = 0.048 < 0.05]. The Pearson correlation between the novelty scores and the D value of brain regions is presented in Table 4. Moreover, a Bonferroni correction has been done based on this number. The α value was set as 0.008(0.05/6). There were significant positive correlations between the novelty and the D value in the frontal (r = 0.736, P < 0.001), parietotemporal (r = 0.594, P = 0.007 < 0.008), and occipital (r = 0.744, P < 0.001) brain regions. This result is consistent with the result of multiple comparisons. It would suggest that the activities of the α band in the frontal, parietotemporal, and occipital regions were highly related to the divergent thinking. An OE statement would help designers get more novel ideas by influencing the divergent thinking of designers.

Table 4. Correlation matrix between the novelty scores and the D value of brain regions

* P < (0.05/6) = 0.008.

Convergent thinking

The average quantitative results of the participants’ convergent thinking (C) in the tasks of different problem statements are shown in Figure 6. The results of ANCOVA showed that there were significant differences between different problem statements and convergent thinking [F(2304) = 65.857, P < 0.01]. The C value for convergent thinking in the DM task is the highest and that in the OE statement task is the lowest. It showed that the DM task has the greatest effect on convergent thinking and the OE task has the least effects. DM is the thinking process of processing and integrating relative information, then putting forward solutions and finally making decisions for specific goals (Redish & Mizumori, Reference Redish and Mizumori2015). In the DM task, the problem-solving process merely involves the organization of existing information; there is no trial and error, and thus no extra cognitive resource is wasted. However, in the OE task, there is insufficient information about the problem, and more cognitive resources are needed to solve the problem. Therefore, the DM task is more helpful for the designers focusing their attention and improving the efficiency of problem-solving markedly.

Fig. 6. Task-related power (TRP) of convergent thinking (C) during the performance of the OE, CO, and DM tasks separately for the left and the right hemispheres. F, frontal; FC, frontocentral; CT, centrotemporal; CP, centroparietal; PT, parietotemporal; O, occipital.

As shown in Figure 6, the left hemisphere displayed a higher C value than that in the right one, as it was evident by an interaction HEMISPHERE and TASK [F(2, 304) = 27.739, P < 0.01]. According to the results of Beeman et al. (Reference Beeman, Bowden and Gernsbacher2000), there were significant differences between the left hemisphere and the right hemisphere in the process of creative problem-solving. In general, the left hemisphere is supposed to relate with cognitive functions such as integrating, judging, and searching information. In the DM and CO tasks, there is much information contained in the question item; designers solve the problem based on convergent thinking through integrating and searching relative knowledge and experiences, with their functional regions of the left hemisphere being activated. It showed that convergent thinking is related to cognitive functions in the left hemisphere.

In addition, there was a significant difference between brain regions with respect to convergent thinking [F(5304) = 38.255, P < 0.01]. The result of multiple comparisons (Bonferroni) of the C value in different regions shows that the C value in centrotemporal and occipital regions displayed better C value that is higher than that in other regions (P < 0.05). This result is supported by some prior studies. For example, Goel and Vartanian et al. (Reference Goel and Vartanian2005) scanned 13 normal participants with fMRI as they completed Guilford's Match Problems (a classic divergent thinking task) and revealed the activation in the right ventral lateral PFC (BA 47) and the left dorsal lateral PFC (BA 46). Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Zhang, Li, Qiu, Tu and Yu2009) found that divergent thinking elicited a more negative ERP deflection (N300–800) over the frontocentral regions. In the design tasks, designers integrate the information about the problem statement (working memory), and search their knowledge and experiences in long-term memory, then get design solutions. This process involves multiple cognitive activities, and activates different brain regions.

The behavior results showed that the DM and CO tasks had a significant effect on conventionality. The conventionality score as a covariate has a significant effect on the C value [F(1, 304) = 6.938, P = 0.009 < 0.01]. The Pearson correlation between the conventionality scores and the C value of brain regions is presented in Table 5. Moreover, a Bonferroni correction has been done based on this number. The α value was set as 0.008 (0.05/6). There were significant differences between the conventionality and the C value in the parietotemporal region (r = 0.645, P = 0.003 < 0.008). The DM and CO statements would help designers reach more practical solutions in creative problem-solving.

Table 5. Correlation matrix between the conventionality scores and the C value of brain regions

* P < (0.05/6) = 0.008.

Mental workload

The average quantitative results of the participants’ mental workload in the tasks of different problem statements are shown in Figure 7. The results of repeated ANOVA showed that there were significant differences between different problem representations with respect to mental workload [F(2304) = 57.337, P < 0.01]. In the frontocentral, centrotemporal, centroparietal, parietotemporal, and occipital regions,the W value for the mental workload in the DM task is the lowest and that in the OE task is the highest. Trejo et al. (Reference Trejo, Knuth, Prado, Rosipal, Kubitz, Kochavi and Zhang2007) put forward that the cognitive recourses in working memory were needed in cognitive processing, while the consumption of cognitive resources increased the mental stress, resulting in mental workload. In the DM tasks, the problem stem contains all the information needed for solving the problem. Problem-solving depends little on the participants’ memories and experiences, so their mental workload is low when they solve such problems. But in the CO and OE tasks, the designers need to solve the problem with their own knowledge and experiences. Because there are fewer constraints to limit the problem space in the OE task than that in the CO task, the problem-solver needs to make more efforts to build a good problem space to search through in the OE task. For this reason, the mental workload in the OE task is higher than that in the CO task.

Fig. 7. Task-related power (TRP) of mental workload (W) during the performance of the OE, CO, and DM tasks separately for the left and the right hemispheres. F, frontal; FC, frontocentral; CT, centrotemporal; CP, centroparietal; PT, parietotemporal; O, occipital.

On the other hand, the interactions of the left/right hemispheres had no obvious difference with respect to mental workload [F(1304) = 0.432, P = 0.649 > 0.05]. This result indicates that in the three statement tasks, activities of the left/right hemispheres cause mental stress, which is consistent with the results of the above functional spectrum analysis.

In addition, there were significant differences between brain regions with respect to mental workload [F(5304) = 137.826, P < 0.01]. The result of multiple comparisons of the W value failed to reach statistical significance in all of the six brain regions. However, as shown in Figure 7, the mental workload value W in centroparietal and occipital regions is apparently increased, indicating that activations in the centroparietal and occipital regions are proportional to the degree of mental workload, and the phenomenon is consistent with the previous studies. Ryu and Myung (Reference Ryu and Myung2005) and Brookhuis and de Waard (Reference Brookhuis and de Waard2010) found that in high mental workload conditions, the activations in the parietal cortex, occipital cortex, thalamus, and cerebellum were all strengthened; and all these brain regions are related to working memory (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Reder, Yuan, Liu and Chen2015). It shows that in the DM tasks, there are low requirements for the designers’ knowledge and experiences (long-term memory). At the same level of task complexity, the task with the DM statement can reduce the designer's mental workload. By comparing the time spent on the three statement tasks in Table 2, it shows that the DM task takes the shortest time and can effectively improve the designers’ problem-solving efficiency.

Conclusions

To explore the influences of different problem statements on human's cognitive behaviors according to a designer's thinking characteristics, the problems are divided into the OE, DM, and CO statements, and the corresponding experiment tasks are set up to investigate the effects of different problem statements on divergent thinking, convergent thinking, and mental workload in this paper. We employed EEG technology to investigate brain activities during the creative problem-solving process.

Through analyzing the experimental data and EEG data of 19 participants, the results are as follows: (1) The OE task is more conducive to the designer's divergent thinking because of less constraint to help get more novel ideas. The α band is activated in the frontal, parietotemporal, and occipital regions of the right hemisphere while designers participate in the OE task. (2) In the DM and CO tasks, there is enough information contained in the question stem, and the designer solves the problem based on convergent thinking through integrating and searching relative knowledge and experiences. The activities of the θ and β bands in the centrotemporal regions of the left hemisphere were related to the convergent thinking. (3) The CO task contains many constraints and the designer needs to combine his/her own knowledge and experiences to solve the problem and then cognitive resources are taken up and it results in a high workload. Mental workload is mainly related to the activations in the centroparietal and parietooccipital regions in the CO task. Therefore, in different stages of product design, different statement information is provided for designers according to the requirements. In the conceptual design, the OE statement information is presented for the designers to get more innovative solutions. In the detailed design, the CO statement information is presented to help designers focus on the problem,then generate practical and feasible solutions. In the solution evaluation, the DM statements should be provided for the designers to solve problems efficiently.

Several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, the difficulty of design tasks and the differences in the knowledge level of the participants were neglected in the experiment. In fact, both would affect the experiment results. Second, although we had tried to control the problem domain in the experiment, the problem domain also placed restrictions on the results. There were also considerable differences in the time spent on problem-solving among the DM, OE, and CO statements. The consumption of cognitive resources and the cognitive behaviors would be changed during the idea generation phase. We will study cognitive behaviors in different stages of the idea generation in the future work. Finally, this is a preliminary and quite limited study. Inferences were made that the manipulation of various facets of problem statements has affected design performance because of their effects on divergent thinking, convergent thinking, and mental workload, although these variables have not measured directly. The results show that the research in cognitive neuroscience may offer interesting insights into the nature of design thinking.

Our conclusions concern two areas for further work. First, the effects of manipulating different problem statements in the design tasks need further examination. Future work should focus on how the negative effects of some aspects of the problem statements in the design tasks, demonstrated in the present studies, can be mitigated so that design performance can be improved. The second area for future work concerns practical issues of how to mitigate the difficulties experienced by novice designers. We propose that this training approach, possibly coupled with the provision of distinct problem statements as aids during the design process, will enable novice designers to better monitor their thinking modes during the design process and therefore improve design performance.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Research Foundation of China (NSFC) (grant no. 51435011) and the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (RFDP) (grant no.20130181130011).

Longfan Liu received the B.E. degree from Sichuan University in 2013. He is currently a Ph.D. Candidate of Mechanical Design and Theory in school of Manufacturing Science and Engineering, Sichuan University, China. His current research interests include innovative design theories and design thinking.

Yan Li received the B.E. and M.E. degrees in Mechanical Engineering from Chengdu University of Science and Technology, China, in 1983, 1986 respectively and the PhD degree from Liverpool John Moores University, UK, in 1996. He is a professor in school of Manufacturing Science & Engineering, Sichuan University. His research interests include Design for innovation; Concept design; Computer Aided Design. He has published more than 140 papers in those areas.

Yan Xiong received the B.E., M.E., and Ph.D. degree from Sichuan University in 1996, 1999 and 2011 respectively. She is currently an Associate Professor in school of Manufacturing Science & Engineering, Sichuan University, China. She is interested in the area of Electroencephalography in creative field, design for innovation, and computer-aided design. She has published 28 papers in those areas.

Juan Cao is currently a postgraduate of Industrial Design in school of Manufacturing Science and Engineering, Sichuan University, China. Her current research interests include industrial design and design cognition.

Ping Yuan received the B.E. and M.E. degrees from Sichuan University in 2009 and 2013 respectively. She is currently a Ph.D. Candidate of Mechanical Design and Theory in school of Manufacturing Science and Engineering, Sichuan University, China. Her current research interests include design thinking and industrial design.