Introduction

‘Reablement’ is home-based care for older people aimed at enhancing their functional independence for daily living, which has been adopted in most high-income countries. In Australia, reablement is recognised in ‘My Aged Care’, the national aged-care policy framework, and is presently implemented through the Regional Assessment Service as an entry-level intervention. However, globally, researchers, practitioners and policy makers have expressed concern about a lack of understanding of reablement as a concept and of a lack of consistency in how it is practised. Our purpose in this paper is to examine the English language literature on reablement critically and represent its typical meaning and practice.

As indicated above, reablement has been widely adopted within the home-based aged-care field, presumably because of evidence and belief that reablement improves health-related outcomes for older people and has the potential to reduce their lifetime cost of care (Francis et al., Reference Francis, Fisher and Rutter2011; Tessier et al., Reference Tessier, Beaulieu, Mcginn and Latulippe2016). Despite this general acceptance of reablement, some researchers have found that ‘reablement’ as a concept lacks clarity in theory and in practice. For example, in their systematic review of evidence of the reablement approach from a global perspective, Legg et al. (Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2016) asserted that reablement was often ill-defined and not restricted to the care of older citizens. Similarly, Moe and Brinchmann (Reference Moe and Brinchmann2016), in their study among service users in Norway, lamented the lack of a sound theoretical basis for reablement, and inconsistencies in how it was defined and applied. Aspinal et al. (Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016), from an international policy and practice perspective, observed inconsistencies in research findings that target specific outcomes of reablement. Parker (Reference Parker2014), in the United Kingdom (UK) added to the claim of conceptual confusion in the social and health-care sector by asserting that reablement is sometimes used interchangeably with three related but distinctive terms: intermediate care, enablement and restorative care.

Furthermore, in practice, reablement has been contested from a range of perspectives. For example, in a study in North Lanarkshire, UK, Miller (Reference Miller2013) bemoaned the lack of service recipient and carer involvement in the reablement process. Pitts et al. (Reference Pitts, Sanderson, Webster and Skelhorn2011), in their discussion paper in the UK, asserted that older people themselves should own and steer their reablement; and the authors further proposed that reablement should be conceived of as a critical policy approach to explore and assess how it affects the life of older people, rather than as a service model. Our aim in this paper is to examine both the concept and the practice of ‘reablement’ as these are represented in the aged and health-care literature globally, guided by the following research questions: (a) What do researchers and practitioners mean by their use of the term reablement and (b) How is reablement practised and how could its practice be improved?

We begin by describing our method for the review, which includes how the articles were selected and how the analysis of data was conducted. We then move on to present and discuss the results of our critical reading on what researchers and practitioners meant by the term reablement. We further discuss the processes involved in implementing reablement, introduce our typology of reablement and tentatively propose a way of improving the practice of reablement.

Review method

In the development of our conceptual framework, we adopted the critical review approach called Search Appraisal Synthesis and Analysis (SALSA), which involves an extensive search and evaluation of the available literature on a topic (Grant and Booth, Reference Grant and Booth2009; Booth et al., Reference Booth, Sutton and Papaioannou2016). In selecting literature for the critical review, we stipulated the following inclusion criteria:

• focuses on reablement for older people;

• provides a clear definition of reablement (mainly as the primary source);

• is available in English and can be sourced electronically; and

• was published between 2005 and 2017.

We further classified the research literature into two components based on its provision of:

• an explicit definition of reablement;

• an articulated practice of reablement and measurement of its outcomes.

When seeking literature on reablement, we mainly used Google Scholar, supported by the Edith Cowan University (ECU) Library online. The ECU online library resources were used to download full papers when they could not be downloaded via Google Scholar. The search terms used via Google Scholar were: (a) ‘definition of reablement’ (1,260 hits) and (b) ‘measurement of reablement’ (1,010 hits).

Sorting the literature into these two search terms allowed us to first compare definitions, practices and outcome measures given that the practices overlapped between the literature on definition and outcome measures; we then categorised these according to emerging common patterns (themes). Our selection of literature resulted in a total of 23 articles for review, as illustrated in Figure 1. The thematic analysis process is embedded in the findings and discussions. The main limitation of the review is our inability to explore the literature on reablement from languages other than English.

Figure 1. Selecting literature for critical review.

Results and discussion

The essential features of reablement

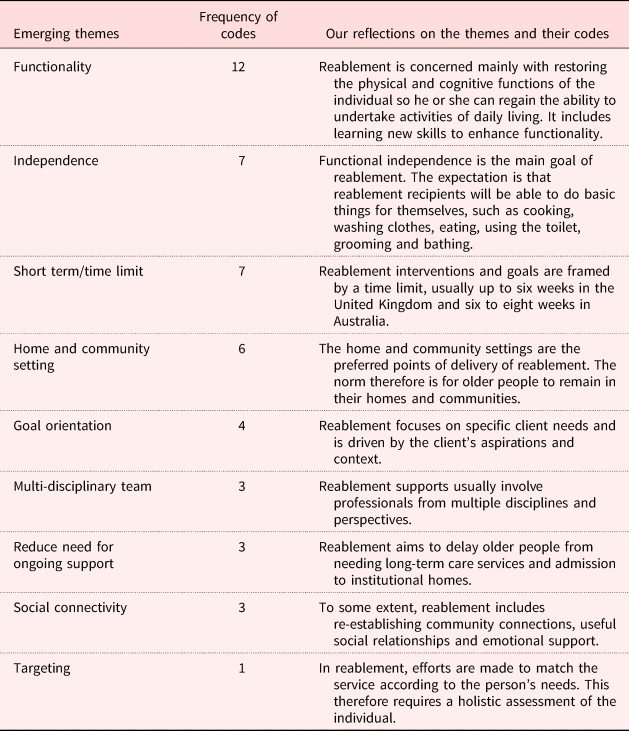

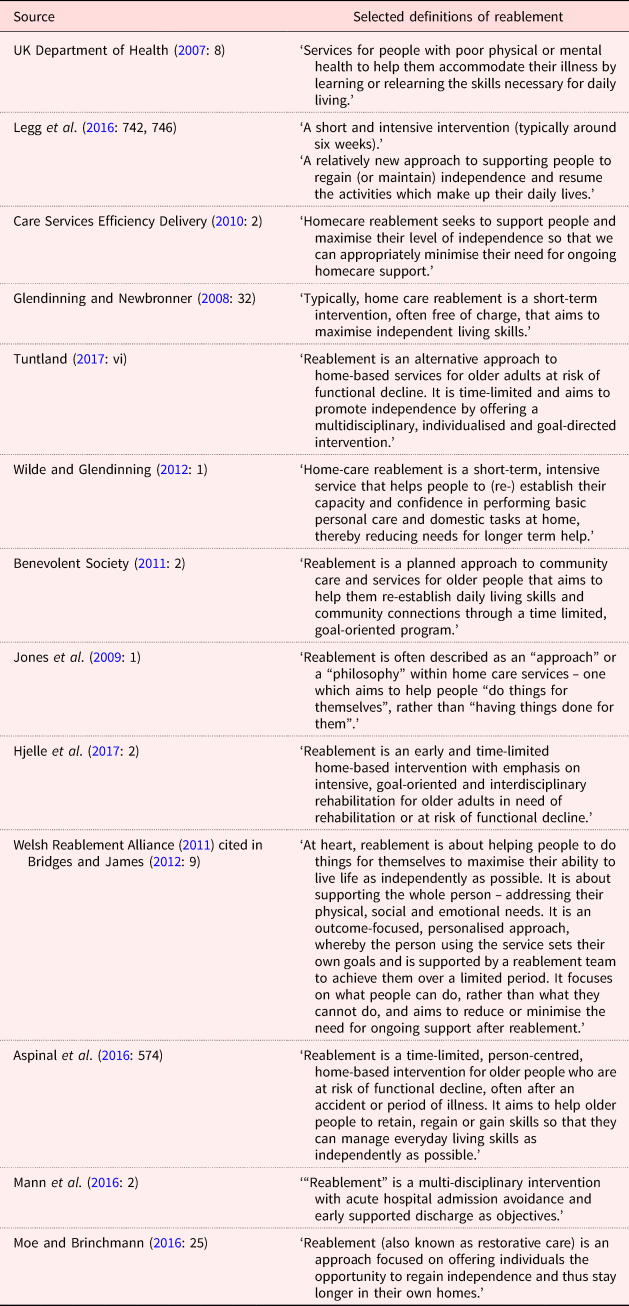

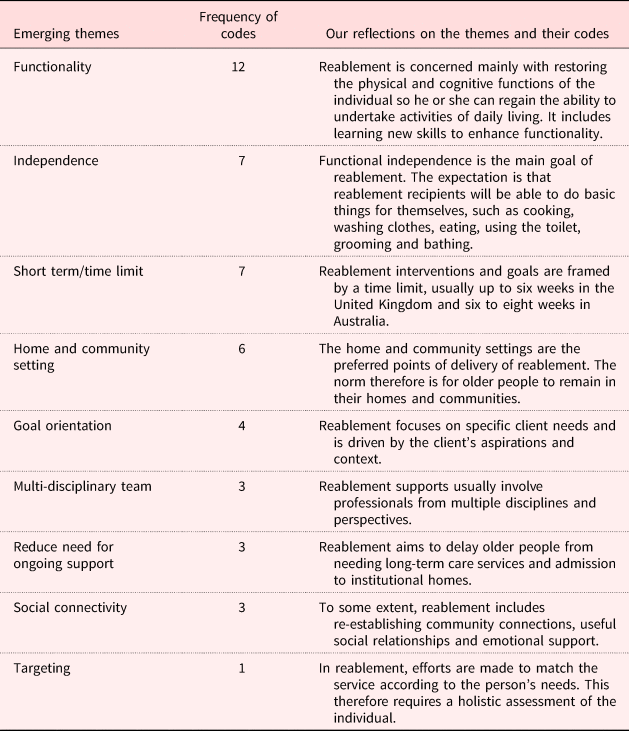

In our attempt to represent how reablement was defined by leading scholars in the field, we examined 14 definitions from 13 sources. Table 1 displays the definitions (as direct quotations) and their respective sources. While there was considerable overlap in these definitions, each of them was distinct. In Table 2, we present the emerging themes from the definitions, based on the thematic analysis and our reflections on these themes.

Table 1. Definitions of reablement

Table 2. Emerging themes and reflections on the definitions of reablement

Table 2 shows the nine themes, representing the essential features of reablement in the literature, that emerged from our thematic analysis. Functionality, the most frequently cited feature of reablement (12, 26.1%), referred to improving the ability of individuals to perform their daily living activities, and included therapies for increasing mobility (e.g. physiotherapy and occupational therapy) and cognition (e.g. stimulation exercises) (Winkel et al., Reference Winkel, Langberg and Wæhrens2015; Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2016; Vernooij-Dassen and Jeon, Reference Vernooij-Dassen and Jeon2016; Tuntland, Reference Tuntland2017).

Another essential feature of reablement in this literature was improving independence, which accounted for 15.2 per cent (seven) of emerging codes. Independence in the context of reablement is the ability and propensity of older people to do things for themselves (Winkel et al., Reference Winkel, Langberg and Wæhrens2015; Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016). In practice, ‘independence’ was envisaged as independence for daily living (Winkel et al., Reference Winkel, Langberg and Wæhrens2015), but there is an emerging interest in incorporating improved cognition, especially for clients with dementia (Poulos et al., Reference Poulos, Bayer, Beaupre, Clare, Poulos, Wang and McGilton2017).

The notion of a time limit emerged as a significant feature of reablement practice, accounting for 15.2 per cent of the emerging codes. The typical time limit prescribed for reablement was 6–12 weeks (Lewin et al., Reference Lewin, Allan, Patterson, Knuiman, Boldy and Hendrie2014; Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016). Thus, reablement is normally conceived of and applied as a short-term intervention.

Home and community setting was another feature of reablement (six, 13%), indicating that reablement occurs in the home and community settings of older people. In some texts, reablement was referred to as home-based reablement (Wilde and Glendinning, Reference Wilde and Glendinning2012; Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Hjelle et al., Reference Hjelle, Tuntland, Førland and Alvsvåg2017).

Other themes that emerged from the data were that reablement was:

(1) Person-centred (i.e. directed towards the needs/wants of the individual clients, with involvement of clients in setting personalised goals for improving their functionality) (five, 10.9%).

(2) Provided by a multi-disciplinary team (three, 6.5%).

(3) Viewed as a strategy for reducing or delaying the need for ongoing support (implying this would avoid further drain on government funds) (three, 6.5%).

(4) Regarded as conducive to social connectivity (i.e. likely to help clients to re-establish community and other social relationships) (three, 6.5%).

Reablement in practice

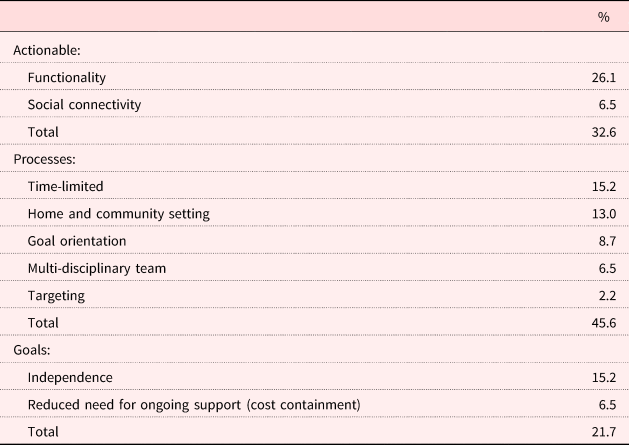

When considering reablement practice, it is necessary to recognise that actions taken in the name of reablement are guided by policy that is more or less clearly articulated. Furthermore, we assumed that practices or processes could and should be classified into either processes (ways of doing something) or goals (aims and intentions). Table 3 shows that from our analysis, five of our emergent themes constituted the process of reablement – how reablement was delivered (45.6%); and two themes (representing 21.7% of codes) showed reablement goals.

Table 3. Essential features of reablement

Collectively, the process themes account for 45.6 per cent of the total code references, which is the highest representation in our analysis. This shows that considerable attention was paid by authors to the processes of reablement implementation, which might explain the extent of variations in implementation across different settings. As stated previously, reablement is normally delivered as a time-limited intervention (Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2016), which varied between 6 and 12 weeks depending on context (Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016). Furthermore, reablement is mainly delivered as a home- and community-based intervention, where older people receive support in their own homes. As indicated above, in terms of the concept of reablement, personal goal setting was thought to be important, but not in all instances (Miller, Reference Miller2013; Hjelle et al., Reference Hjelle, Tuntland, Førland and Alvsvåg2017).

In practice, reablement has a strong focus on clients improving their functionality (Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, McGilloway, Furlong, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2013) and the practice of reablement tends to be led and supervised by allied health professionals, such as occupational therapists or physiotherapists. However, as noted above, some of the literature suggests that reablement is delivered by a multi-disciplinary team (Bridges and James, Reference Bridges and James2012; Mann et al., Reference Mann, Beresford, Parker, Rabiee, Weatherly, Faria and Aspinal2016; Hjelle et al., Reference Hjelle, Tuntland, Førland and Alvsvåg2017; Tuntland, Reference Tuntland2017). Finally, part of the reablement delivery process is the targeting aspect, which usually begins with an active assessment to determine the kind of support strategies required by each client.

In the UK, Australia and New Zealand, most reablement services comprise clients’ skills learning or relearning how to perform specific daily activities (Glendinning et al., Reference Glendinning, Jones, Baxter, Rabiee, Curtis, Wilde and Forder2010; Benevolent Society, 2011; King et al., Reference King, Parsons, Robinson and Jörgensen2012). There is also the use of assistive technology, such as hearing aids; specialised seating and other home modifications to enhance the functionality of older people (Lewin et al., Reference Lewin, De San Miguel, Knuiman, Alan, Boldy, Hendrie and Vandermeulen2013b; Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2013); the use of occupational therapy (Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2012); and outreach/leisure programmes to enhance the communal and social life of older people (Leeds City Council Communications, 2011). In some cases, reablement is supplemented with general social support services, such as help with basic household chores (Rabiee et al., Reference Rabiee, Glendinning, Arksey, Baxter, Jones, Forder and Curtis2009).

What are the goals of reablement?

The overall goal of reablement is the improved functionality and independence of clients. It follows that assessing individuals’ progress on their personalised goals within a specified period is a key component of reablement practice (Miller, Reference Miller2013); and presumably there are both short-term and long-term outcomes targeted for each client. Moreover, there are systemic goals for reablement set by the sponsoring/funding body, such as reducing the need for ongoing support and cost containment.

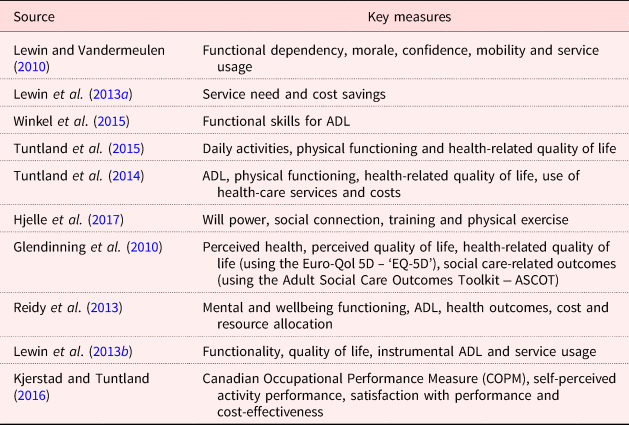

In our review of literature, we also identified research evaluations in which selected outcomes were measured (see Table 4). It is clear from these studies that the outcome measures focused largely on functional independence, which is consistent with the emerging meaning of reablement shown in Tables 2 and 3. For example, Lewin and Vandermeulen's (Reference Lewin and Vandermeulen2010) evaluation of the Home Independence Program in Australia focused on improving functional dependency, morale, confidence, mobility and service usage. Similarly, Tuntland et al. (Reference Tuntland, Espehaug, Forland, Hole, Kjerstad and Kjeken2014, Reference Tuntland, Aaslund, Espehaug, Førland and Kjeken2015) and Winkel et al. (Reference Winkel, Langberg and Wæhrens2015) focused on functional independence in their outcome measures of various reablement programmes mainly in Norway. Other outcome measures in the literature were: the cost-effectiveness of reablement (Lewin et al., Reference Lewin, Alfonso and Alan2013a; Tuntland et al., Reference Tuntland, Espehaug, Forland, Hole, Kjerstad and Kjeken2014; Kjerstad and Tuntland, Reference Kjerstad and Tuntland2016), health-realted outcomes, self-rated quality of life and social care-related outcomes (Glendinning et al., Reference Glendinning, Jones, Baxter, Rabiee, Curtis, Wilde and Forder2010).

Table 4. Selected outcome measurements of reablement

Note: ADL: activities of daily living.

Note that, except for Hjelle et al. (Reference Hjelle, Tuntland, Førland and Alvsvåg2017), reablement outcome measures focused on individual functionality. This bias and its implications will be taken up in the Conclusion.

Improving reablement practice

Our review shows that in all instances where the setting was made explicit (six, 16%) reablement was delivered to older people in their own homes and within their community (Glendinning and Newbronner, Reference Glendinning and Newbronner2008; Wilde and Glendinning, Reference Wilde and Glendinning2012; Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Hjelle et al., Reference Hjelle, Tuntland, Førland and Alvsvåg2017). A few other studies (three, 6.5%) referred to social and community connection in reablement (Hjelle et al., Reference Hjelle, Tuntland, Førland and Alvsvåg2017; Benevolence Society, 2011). Incidentally, the literature provided firm support for the proposition that older people prefer to age in their own homes and community rather than in residential care (Wiles et al., Reference Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve and Allen2012; Van Dijk et al., Reference Van Dijk, Cramm, Van Exel and Nieboer2015).

In practice, given the growing preference for home- and community-based aged care, considerable attention needs to be paid to how the home and community – including social and community connections (social connectivity) – can enhance the quality of life of people as they age. We contend that the current reablement approach, which is highly functionality oriented, would benefit from more emphasis on enhancing the social connectivity of clients. Thus, we made a further classification of the body of literature in our review – the aspect that focuses on improving functional independence and the aspect that focuses on ensuring that the community and home condition is conducive to social connectivity.

Then, as shown in Figure 2, we combined the focus in reablement on functionality with the focus on enhancing social connectivity to produce a typology of four theoretical types: (a) functional, (b) critical, (c) stable and (d) social. We labelled the reablement context with high functional focus and high social connectivity focus as ‘critical reablement’. Critical reablement implies that practitioners should pay attention to improving both functionality and social connectivity equally to mitigate what Aspinal et al. (Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016) described as the side-effect of reablement – social isolation. We labelled high functional focus with low social connectivity focus as ‘functional reablement’, whereby practitioners focus almost exclusively on improving client functionality – which is the dominant practice model according to our review. In a situation where functional focus is low and social connectivity focus is high, we labelled this ‘social reablement’. Social reablement from our perspective means that the client has functionality stable but may be experiencing isolation. This context will require enhancing the social connectivity of the client. Finally, we labelled the context where there is low functional focus and there is low social connectivity as ‘stable reablement’. By stable reablement, we mean a situation where the client is functionally stable and socially connected. Stable reablement may be considered to be the optimum state for clients in reablement.

Figure 2. Theoretical types of reablement.

Conclusion

In this study, we conducted a critical literature review of both concept and practice in reablement, and from our review we built a theoretical typology of reablement with a view to improving reablement practice. Overall, we found nine main features in how reablement was defined, with functionality as the most prominent. Other features of reablement definition include its aim for independence of clients, the time-limited nature of interventions, the focus on personalised goal orientation, its multi-disciplinary team approach, its intention to reduce the need for ongoing support, its locus on home and community settings, and the small amount of consideration for the social connectivity of clients.

Based on these data, we noted that the primary actions/practices of reablement have been directed towards improving clients’ mobility, ability to perform the activities of daily living and cognition, so they are able to continue to live independently. Some of these actions involved providing physiotherapy, occupational therapy, assistive technology and mental stimulation activities. We further derived from our analysis that the practice of reablement typically included a time limit, goal setting, multi-disciplinary team, community setting and targeting. As can be seen, there is a considerable degree of overlap in our dual foci of meaning and practice.

We contend that the processes of reablement, with their dynamism and degree of context dependence, are bound to result in variability. But we are not comfortable about depicting the variability as ‘lack of consistency’; we view it as a human inevitability. Although we acknowledge the importance of the dominant emphasis on client functionality in reablement practice, we are convinced that more attention by both practitioners and researchers should be given to clients’ social connectivity.

The research and process implications for this shift in emphasis are quite profound. On the one hand, methodologically, there would be more concern for investigating the socially constructed realities of home and community contexts – as perceived by the clients. But determining these realities would necessarily be more labour intensive: more observational and less a matter of ‘ticking’ (pre-conceived) boxes about whether a client has acquired a certain skill. Such a shift, especially for practitioners, would have further implications in terms of political and bureaucratic imperatives. For now, however, we merely gently ‘lift the lid’ for a quick peek at this prospect for future research and practice, and we offer our typology as a conceptual question to prompt future investigations.

Author ORCIDs

Daniel Doh, 0000-0002-7352-6121.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our gratitude to Access Care Network Australia (ACNA) for providing the opportunity, space and facility to carry out this review. We are also thankful to the Edith Cowan University for access to most of the literature we used in this review. Finally, we are grateful to Professor Gill Lewin and Dr John Hall for their feedback on the initial draft manuscript.