Introduction

Reminiscence has attracted much attention from gerontology researchers. Many acclaimed scholars, including Bühler, Jung, Havighurst and Neugarten, have argued that reminiscence is a ‘natural process’ through which positive and negative memories are balanced in the light of life's finitude. In his stage theory of lifespan development, Erikson (Reference Erikson1959) most clearly formulated the last stage of life as a period of life review. A successful life review achieves an integrated view of one's past life, including positive memories and achievements alongside the reconciliation and acceptance of failures and disappointments, and results ideally in wisdom, the experience of meaning in life, and the acceptance of one's own death. It was Butler's (Reference Butler1963) seminal article, ‘The life-review: an interpretation of reminiscence in the aged’, which initiated the first empirical studies and practical applications of reminiscence among older people. Previously reminiscence had often been seen as a corollary of cognitive decline, but Butler argued that life review has a positive function in helping a person come to terms with unresolved conflicts from the past and with his or her approaching vulnerability and death. The process of life review would thus be functional for older adults from a mental health perspective. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, several reviews of the early work were published (Haight Reference Haight1991; Kovach Reference Kovach1990; Molinari and Reichlin Reference Molinari and Reichlin1984; Thornton and Brotchie Reference Thornton and Brotchie1987; Webster Reference Webster1994; Webster and Haight Reference Webster, Haight, Haight and Webster1995). They generally concluded that there was a need for more precise definitions and measurements and better studies of the effects of interventions.

For the last two decades, researchers have responded to these criticisms and instigated a new phase of reminiscence research, which is the subject of this review. We first discuss accounts of reminiscence as a ‘naturally occurring process’, define the phenomenon and describe its different types and functions. In the second section, we discuss the evidence for the relationship between reminiscence and mental health. The third section relates reminiscence to lifespan processes, and in the final section we consider the implications of recent research on reminiscence as a social or therapeutic intervention, including the different functions it achieves and its role in restoring and optimising mental health.

Reminiscence as a naturally occurring process

Definitions of reminiscence

Although in everyone's vocabulary reminiscence refers to the recall of memories about one's own life, it has proven difficult to provide a robust scientific definition (Fitzgerald Reference Fitzgerald and Rubin1996). The most inclusive definition is that provided by Bluck and Levine (Reference Bluck and Levine1998: 188). It incorporates all aspects of the phenomenon of remembering our lives and is adopted in this review:

Reminiscence is the volitional or non-volitional act or process of recollecting memories of one's self in the past. It may involve the recall of particular or generic episodes that may or may not have been previously forgotten, and that are accompanied by the sense that the remembered episodes are veridical accounts of the original experiences. This recollection from autobiographical memory may be private or shared with others.

We stress three important elements of this definition. First, it makes clear that reminiscence is something which happens to us all in our everyday lives, whether we share our memories or not. This is the basis for describing reminiscence as a ‘naturally occurring phenomenon’ throughout the lifespan. Second, the definition draws attention to the fact that memories of our lives can be wilfully recollected, and even that memories thought to be forgotten can be recalled. This volitional recall is the cornerstone for reminiscence as a useful intervention. Third, it describes memories as veridical (‘speaking, telling, or relating the truth; truthful, veracious’, Oxford English Dictionary online). It is nowadays generally understood that remembering not only involves the simple recall of instances from long-term memory, but also that memories are reconstructed in relation to existing schemas about the self, and vice versa (Bluck and Levine Reference Bluck and Levine1998; Conway, Singer and Tagini Reference Conway, Singer and Tagini2004; Wilson and Ross Reference Wilson and Ross2003). When memories are shared with other persons, the retelling is tuned to the social situation at hand (Marsh Reference Marsh2007; Pasupathi Reference Pasupathi2001). This reconstructive nature of reminiscence makes it difficult to grasp, yet it also provides a second cornerstone for believing that reminiscence interventions can be beneficial.

Types of reminiscence and their measurement

Bluck and Levine's definition makes clear that reminiscence has different forms, but which have been distinguished? While the earliest reminiscence researchers recognised there are different types (e.g. Coleman Reference Coleman1974, Reference Coleman1986; Lo Gerfo Reference Lo Gerfo1980; McMahon and Rhudick Reference McMahon and Rhudick1964), more recent scholars have attempted to measure their relative frequencies in informants' self-reports (Habegger and Blieszner Reference Habegger and Blieszner1990; Havighurst and Glasser Reference Havighurst and Glasser1972; Merriam Reference Merriam1993; Santor and Zuroff Reference Santor and Zuroff1994) and by content analysis (Kovach Reference Kovach, Haight and Webster1995). These early taxonomies and measures were limited, however, and not widely adopted (Webster Reference Webster2003).

Wong and Watt (Reference Wong and Watt1991) made the first substantial attempt to develop an empirically grounded taxonomy of reminiscence on the basis of previous research and using content analysis of a large corpus of reminiscence data. They asked 200 community-dwelling subjects and 200 people living in institutions aged 65 or more years to ‘tell something about your past that is most important to you – that is something that has had the most influence on your life’ (1991: 275). An exhaustive and reliable coding scheme was developed to score the responses into the different reminiscence types, and six forms were identified (see Table 1, column 2). Integrative reminiscence refers to the type of life review recognised in the early literature, although not all instances are necessarily related to death preparation. Instrumental reminiscence includes recollections of one's planning and coping behaviours in the past. Transmissive reminiscence involves telling memories to inform younger generations about one's cultural heritage or personal legacy. Narrative reminiscence concerns recounting autobiographical information and past anecdotes. Escapist reminiscence refers to positive recollections, expressing nostalgia for the past. Obsessive reminiscence, by contrast, reiterates negative memories, and is evinced by guilt, bitterness and despair.

Table 1. The types and functions of reminiscence

Note: rels: relationships.

Webster (Reference Webster1993, Reference Webster1997) used factor analysis to distinguish different uses of reminiscence. The resulting Reminiscence Functions Scale (RFS) has 43 items that begin with the stem, ‘When I reminisce it is’ and continue with a selected specific purpose, for example ‘to reduce boredom’. The items generate eight components or sub-scales that have good reliability, most above 0.8. Webster (Reference Webster1997: 140) labelled these as:

Identity: The existential use of the past to discover, clarify or crystallise our sense of who we are.

Death preparation: The way we use our past in order to arrive at a calm and accepting attitude towards our own mortality.

Problem solving: The use of reminiscence as a constructive coping mechanism by remembering past problem-solving strategies.

Teach/inform: An instructional type of reminiscence to relay personal experiences and life lessons to others.

Conversation: The informal use of memories in order to connect or reconnect to others.

Boredom reduction: Thinking back about the past to escape an under-stimulating environment or a lack of engagement in goal-directed activities.

Bitterness revival: The recall of memories about unjust treatments, providing the justification to maintain negative thoughts and emotions to others.

Intimacy maintenance: A process whereby cognitive and emotional representations of important people in our lives are resurrected in lieu of the remembered person's physical appearance.

Although Webster used a very different methodology, six factors of the RFS correspond by and large to the six types distinguished by Wong and Watt (Reference Wong and Watt1991) (see Table 1, columns 2 and 3). They saw death preparation as part of integrative reminiscence (1991: 273), so intimacy maintenance is the only type of reminiscence that Webster added to Wong and Watt's typology.

It is tempting to try to reduce the eight different functions to a smaller number. Cappeliez, Rivard and Guindon (Reference Cappeliez, Rivard and Guindon2007) argued that there are three main clusters of reminiscence functions (see Table 1, column 4). The first are mainly directed towards the self and concern the striving for meaning and coherence in life. The associated positive functions for the self are identity construction and death preparation, whereas negative self-functions are boredom reduction and bitterness revival. The second cluster relates to social bonding and emotion regulation and includes intimacy maintenance as a negative function and conversation as a positive function. The last cluster, called guidance, relates to private or shared knowledge and experience, and has the reminiscence functions of problem solving and teaching or informing others.

Bluck and Alea (Reference Bluck, Alea, Webster and Haight2002) also tried to reduce the number of functions using theory. They compared the functions of reminiscence to three functions of autobiographical memory: self, directive, and social (see Table 1, column 5), and argued that identity construction and death preparation are functional for the self, most importantly to maintain continuity. Problem-solving reminiscence matches the directive function of autobiographical memory, whereas teaching/informing, conversation and intimacy maintenance correspond to the social function. Bitterness revival and boredom reduction did not match any of the functions of autobiographical memory. These theoretical clusters of reminiscence functions arrange well the reminiscence self-functions, but there is some disagreement about whether teaching/informing belongs to the guidance or the social cluster. One way to resolve this theoretical inconsistency is to study the empirical relations between the occurrences of different types of reminiscence.

Recent empirical evidence

Webster (Reference Webster2003) conducted a secondary factor analysis and a discriminant analysis on the eight reminiscence functions, using data from four independent studies with participants aged from 17 to 96 years. The functions could be arranged in a circumplex model with two axes: self versus social and reactive/loss-oriented versus pro-active/growth-oriented (see Table 1, column 6). The identity construction and problem-solving functions fall in the pro-active self quadrant, conversation and teaching/informing in the pro-active social quadrant, intimacy maintenance and death preparation in the reactive social quadrant, and bitterness revival and boredom reduction in the reactive self quadrant. Webster (Reference Webster2003) acknowledged that this ordering of reminiscence functions was tentative, particularly the position of death preparation.

Using data from a study with participants aged between 50 and 84 years, Cappeliez and O'Rourke (Reference Cappeliez and O'Rourke2006) partly replicated these findings using structural equation modelling (see Table 1, column 7). They found three rather than four factors, splitting the factor that combined death preparation and intimacy maintenance. Death preparation loaded on the same factor as identity construction and problem solving, which they labelled self-positive. Intimacy maintenance loaded together with bitterness revival, and boredom reduction on a factor called self-negative. To teach and to converse made up the third pro-social factor, similar to that found by Webster (Reference Webster2003).

Bluck et al. (Reference Bluck, Alea, Habermas and Rubin2005) carried out an empirical study among undergraduate students on the relation between functions of autobiographical memory and uses of reminiscence. They constructed a scale called Thinking About Life Experiences (TALE) to measure the self, directive and social functions of autobiographical memory. The scale showed four factors with the social function being bi-dimensional: self-continuity, directive, nurturing relationships, and developing relationships. Bluck and colleagues correlated the four sub-scales of TALE with the eight sub-scales of Webster's RFS, and applied the criterion of a minimum correlation coefficient of 0.50 to identify associations (see Table 1, column 8). The factors self-continuity, directive, and nurturing relations showed high correlations with respectively Identity, Problem Solving, and Conversation of the RFS. These findings evince the concurrent validity of both scales. Self-continuity also related to Problem Solving, however, and the directive function also correlated with Identity, suggesting that the discriminant validity of the sub-scales may not be high. The TALE sub-scale Developing Relationships was not strongly related to RFS sub-scales, and the other RFS sub-scales were not highly correlated with the other TALE sub-scales.

It has become clear that reminiscence has many different forms. At least eight uses of reminiscence have been reliably distinguished by different types of research. The RFS is the best available way to assess these different uses (Webster Reference Webster1993, Reference Webster1997), but it remains an open question whether the eight uses are really distinct or correlate strongly enough to justify a more parsimonious taxonomy. The two most contested issues, both theoretically and empirically, relate to (a) the position of intimacy maintenance and death preparation, and (b) whether identity construction and problem solving are distinct or similar functions. These contested issues derive partly from the diversity of reminiscence's functions. Our view is that more clarity will come when the different uses of reminiscence are studied in relation to individual functions. As it has often been argued that reminiscence impacts on mental health, the following section focuses on the evidence for this relationship. The reasoning is that if different uses of reminiscence have similar relations to mental health, they can be considered as similar types.

Reminiscence and mental health

Although it has long been assumed that reminiscence is adaptive in old age, studies in the early years of reminiscence research produced conflicting results (Wong and Watt Reference Wong and Watt1991), which might be because they addressed different types of reminiscence, or because initially it was not recognised that life review can be obsessive or stagnant (Coleman Reference Coleman1986). Along with the increased awareness of the different types and uses of reminiscence in recent years, the focus has shifted from whether reminiscence is adaptive to determining which types are adaptive. Unfortunately, almost all studies to date of the relationship between reminiscence and mental health have been cross-sectional (seeColeman Reference Coleman1986 for an exception based on qualitative case studies). It is therefore impossible to draw conclusions about causality: particular uses of reminiscence might result in better mental health, but better mental health might also lead to particular uses of reminiscence.

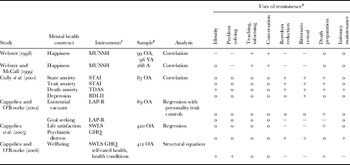

Six studies have used the RFS in relation to mental health, as summarised in Table 2. Webster (Reference Webster1998) and Webster and McCall (Reference Webster and McCall1999) found that reminiscence functions are related to happiness. Bitterness revival, boredom reduction, identity construction and problem solving were negatively related to happiness, whereas conversation and teaching/informing were positively related to feelings of happiness. Cully, LaVoie and Gfeller (Reference Cully, LaVoie and Gfeller2001) found that state and trait anxiety correlated with bitterness revival, boredom reduction and death preparation, whereas depression associated only with bitterness revival. Using a canonical analysis of reminiscence functions, indicators of mental health and personality traits, they identified two canonical variates. The first suggested that individuals with lower levels of anxiety and depression and who are less neurotic and more agreeable tend to use reminiscence comparatively infrequently for bitterness revival, boredom reduction and death preparation. The second variate suggested that individuals high on extraversion and openness and with lower levels of depression tend to reminisce frequently for teaching and conversing.

Table 2. Relationships between reminiscence functions and wellbeing

Notes: 1. MUNSH: Memorial University of Newfoundland Scale of Happiness (Kozma, Stones and McNeil Reference Kozma, Stones and McNeil1990). STAI: State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger, Gorsuch and Lushene Reference Spielberger, Gorsuch and Lushene1970). TDAS: Templer-McMordie Death Anxiety Scale (McMordie Reference McMordie1979). BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory, revised (Beck, Steer and Brown Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1996). LAP-R: Life Attitude Profile, revised (Reker Reference Reker1992). SWLS: Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener et al. Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985). GHQ: General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg Reference Goldberg1978). 2. A: adults. OA: older adults. YA: younger adults. 3. 0 indicates no relation;+indicates a positive relation (e.g. more teaching/informing is related to higher levels of happiness); −indicates a negative relation (e.g. more boredom reduction is related to lower levels of happiness).

Cappeliez and O'Rourke (Reference Cappeliez and O'Rourke2002) studied the relation between reminiscence functions and meaning in life after controlling for personality traits. They found that a lower score on goal-seeking as a component of meaning in life related to a greater use of boredom reduction, bitterness revival and death preparation, and a higher score on existential vacuum, indicating a lack of meaning in life, related to a higher score on death preparation. A recent study of 420 adults with a mean age of 61 years investigated the association of reminiscence functions with life satisfaction and psychological distress (Cappeliez, O'Rourke and Chaudhury Reference Cappeliez, O'Rourke and Chaudhury2005). When controlling for personality traits, boredom reduction and bitterness revival related to lower life satisfaction, whereas death preparation related to higher life satisfaction. Boredom reduction, bitterness revival and maintenance of intimacy with deceased persons related to psychological distress, but these associations could be explained by personality traits. Cappeliez and O'Rourke (Reference Cappeliez and O'Rourke2006) calibrated a structural equations model using the same data that related reminiscence functions to wellbeing (including life satisfaction, psychological distress, perceived health, and health conditions). The reminiscence functions of identity, death preparation and problem solving positively related to wellbeing, and the functions of boredom reduction, bitterness revival, and intimacy maintenance were negatively related, but the pro-social functions conversation and teaching/informing were unrelated.

To sum up, studies have produced inconsistent findings, in part because they have used different measures of mental health. The findings for bitterness revival and boredom reduction are the most consistent: these uses of reminiscence are negatively related to almost all the aspects of mental health that have been studied. Intimacy maintenance also shows a negative relation to mental health, but not for all aspects. Conversation and teaching or informing tend to be unrelated to mental health, with the exception of a positive association with happiness. Some studies have found that identity, problem solving and death preparation are negatively related to mental health, and some have found positive associations.

Earlier in the paper we reviewed the various attempts to classify the uses of reminiscence, as summarised in Table 1. The evidence from studies of the relationships between different forms of reminiscence and mental health supports the view that some ways of reminiscing are not only similar from a theoretical perspective and in terms of their factor structure, but also in their relation with mental health: bitterness revival and boredom reduction are similarly dysfunctional, whereas conversation and teaching/informing tend to be unrelated to mental health, with the exception of their positive relation to happiness. Studies on the relations of reminiscence with mental health shed a new light on the two remaining inconsistencies in the classification of reminiscence functions. First, the position of death preparation and intimacy maintenance remained unclear. At least from a mental health perspective, the function of death preparation is similar to those of identity construction and problem solving, whereas intimacy maintenance has similar dysfunctional outcomes to those of bitterness revival and boredom reduction. Second, although identity construction and problem solving are theoretically distinct, it proved difficult to distinguish them empirically. The evidence that they associate similarly with mental health supports the conclusion that both functions are similar, which has added plausibility when reminiscence is related to theories about lifespan processes.

Lifespan processes

It was long assumed that reminiscence is specific to late life and universal among older people, but evidence is accumulating that neither is the case. Coleman (Reference Coleman1986) was one of the first to show that reminiscence is not universal, and that it is not always useful for adaptation to later life. He distinguished reminiscers and non-reminiscers in a sample of 50 older people and found cases of low and high morale in both groups. Some (42% of the 50) reminiscers valued their memories of the past, and some (16%) were troubled by their memories. Some (30%) non-reminiscers saw no point in looking back, and some (12%) more or less actively avoided looking back because of contrasts between their past and present lives. Using a single dichotomous question on life review put to older respondents, Merriam (Reference Merriam1993) found that about 54 per cent reported that they had or were currently engaged in a life review. Wink and Schiff (Reference Wink, Schiff, Webster and Haight2002) rated the responses to interviews that covered all main aspects of current and past psychological and social functioning on a five-point scale to indicate the level of life review in the transcript: 22 per cent had used reminiscence to reach a new level of self-understanding (score 4 or 5), 20 per cent showed emotional involvement in the process of reminiscing without evidence for new self-understanding, and the remainder had not used reminiscence or only gave descriptions of past personal events. Reminiscence is therefore not a universal phenomenon in old age.

Other studies have shown that reminiscence is also not distinctive to old age. Using simple questions on the frequency of reminiscing, Merriam and Cross (Reference Merriam and Cross1982) and Hyland and Ackerman (Reference Hyland and Ackerman1988) found that adolescents reminisced as often as older adults, and that middle-aged people reminisced less frequently. Recent studies using the RFS have consistently shown that there are no age differences in the total amount of reminiscing (Rybash and Hrubi Reference Rybash and Hrubi1997; Webster Reference Webster, Haight and Webster1995, Reference Webster1998, Reference Webster, Webster and Haight2002; Webster and Gould Reference Webster and Gould2007; Webster and McCall Reference Webster and McCall1999). Pasupathi and Carstensen (Reference Pasupathi and Carstensen2003) studied age differences in emotional experiences during mutual reminiscence in adulthood, and found that age was unrelated to the amount of such reminiscence. As their study used experience sampling, the findings would not be affected by the bias in self-report methods used in other studies.

Although the total amount of reminiscence does not vary by age, younger and older adults use it for different purposes. Younger adults consistently report reminiscing more often for bitterness revival, boredom reduction, identity construction and problem solving, whereas older adults report reminiscing more frequently for death preparation and to teach/inform others (Rybash and Hrubi Reference Rybash and Hrubi1997; Webster Reference Webster, Haight and Webster1995, Reference Webster1998, Reference Webster, Webster and Haight2002; Webster and Gould Reference Webster and Gould2007; Webster and McCall Reference Webster and McCall1999). All studies agree that there are no age differences in reminiscing to make conversation. Some studies have shown that older persons score higher on intimacy maintenance (Webster Reference Webster, Haight and Webster1995, Reference Webster1998; Webster and Gould Reference Webster and Gould2007), whereas others have not (Rybash and Hrubi Reference Rybash and Hrubi1997; Webster Reference Webster, Webster and Haight2002; Webster and McCall Reference Webster and McCall1999). Interestingly, the finding that older people use reminiscence more often for death preparation is in line with the earlier assumption that life review is a distinctive characteristic of old age. It is by broadening the definition of reminiscence that it becomes clear that it is not reminiscence as such that is characteristic of old age, but its distinctive uses.

The recent empirical studies have shown unequivocally that reminiscence is a lifespan phenomenon, which interestingly goes hand-in-hand with a theoretical shift. Psychological theories on ageing have increasingly taken a lifespan perspective, rather than conceiving old age as a distinct phase of life. Reminiscence is therefore no longer seen as an adaptation to the increasing awareness of one's finitude, but as an important process in regulating individual development throughout the lifespan. Scholars such as Whitbourne (Reference Whitbourne, Birren and Schaie1985), Thorne (Reference Thorne2000) and Pasupathi, Weeks and Rice (Reference Pasupathi, Weeks and Rice2006) describe remembering as a key process in development from early to late adulthood. This basic idea has been developed in at least three theories on lifespan development.

Reminiscence and theories of lifespan development

One psychological theory that has been applied to reminiscence is the socio-emotional selectivity theory (Carstensen Reference Carstensen1995, Reference Carstensen2006). This proposes that individuals have two important motives in life: emotion regulation and information gain. In later life, motivational priorities shift so that the regulation of emotional states becomes more important than information gain. This theory emphasises that it is not age as such but the awareness of endings which originates this shift. One important finding of socio-emotional selectivity is known as the ‘positivity’ effect: ‘a developmental pattern that has emerged in which a selective focus on negative stimuli in youth shifts to a relatively stronger focus on positive information in old age’ (Carstensen Reference Carstensen2006: 1915). Socio-emotional selectivity theory has been applied to reminiscence in the work of Pasupathi and Carstensen (Reference Pasupathi and Carstensen2003). They studied the age differences in emotional experiences during mutual reminiscence in adulthood, using an experience-sampling methodology. As we have seen, they found that age was unrelated to the amount of mutual reminiscing, but older people experienced more positive emotions during mutual reminiscing than younger people. As no age differences were found in the emotions of people who were engaged in other social situations, this positivity effect appears to result from reminiscence. A second study by Pasupathi and Carstensen showed that the positivity effect arises because older adults relived the positive quality of the initial event more than younger people.

The second theory is that of continuity theory (Atchley Reference Atchley1989, Reference Atchley and Kelly1993), which holds that experiencing continuity is essential to an individual's mental health and functioning. Atchley distinguished two ways of maintaining a sense of continuity. External continuity refers to the preservation of one's life circumstances, whereas internal continuity concerns the preservation of one's own sense of identity. Both kinds are challenged when important life events disrupt an individual's life, as with the age-related life events of retirement and the onset of frailty (Atchley Reference Atchley and Kelly1993). To maintain a sense of continuity, individuals ‘attempt to preserve and maintain existing internal and external structures and they prefer to accomplish this objective by using strategies tied to their past experiences of themselves’ (Atchley Reference Atchley1989: 183). The resulting sense of continuity, with the aid of reminiscence, is expected to promote adaptation. Continuity theory has been applied to reminiscence most explicitly by Parker (Reference Parker1995, Reference Parker1999). The theory assumes that people reminisce more frequently during periods of personal transition than during stable periods. From her empirical research using self-reports on the amount of reminiscing during transitional periods, Parker found that young people were more likely to reminisce than older adults, although older adults reported more positive emotions when reminiscing. Studies of temporal comparisons have also found evidence of the importance of continuity across the lifespan. Individuals who see stability in their lives were found to have higher levels of wellbeing than those who see change, even when this change is appraised as improvement (Keyes Reference Keyes2000; Westerhof and Keyes Reference Westerhof and Keyes2006).

Besides these theories which focus on emotional regulation and continuity, the lifespan theory of control has been applied to reminiscence (Schulz and Heckhausen Reference Schulz and Heckhausen1996). This theory holds that individuals strive throughout the lifespan to maintain a sense of control over their lives. This can be achieved through either primary or secondary control: ‘primary control targets the external world and attempts to achieve effects in the immediate environment external to the individual, whereas secondary control targets the self and attempts to achieve changes directly within the individual’ (1996: 708). In later life, individuals are expected to shift from primary to secondary control strategies. Secondary control strategies may also involve a process of reminiscence.

In its application to reminiscence, the theory has focused on a particular class of memories: regrets (Wrosch, Bauer and Scheier Reference Wrosch, Bauer and Scheier2005; Wrosch and Heckhausen Reference Wrosch and Heckhausen2002). An important assumption in these studies is that, with advancing age the length of a person's anticipated remaining life shortens, so it becomes more difficult to modify regretted life paths. Wrosch and Heckhausen (Reference Wrosch and Heckhausen2002) found that attributions of internal control were related to high-intensity regret among older adults, but associated with low-intensity regret among younger people. From a second study, Wrosch and colleagues (Reference Wrosch, Bauer and Scheier2005) showed that among older people who were disengaging from the goals associated with the regrets, having other future goals moderated the relation between the intensity of regret and quality of life. Both studies confirmed that secondary control strategies dealing with life regrets are more important in old age than at younger ages. The findings of Timmer, Westerhof and Dittmann-Kohli's (Reference Timmer, Westerhof and Dittmann-Kohli2005) study of German and Dutch people aged between 40 and 85 years also supported this idea that older people are more proficient in using secondary control strategies when dealing with regrets. They found that they had fewer regrets and more often gave them external attributions than those of middle age.

Although these three theories have different perspectives, they all subscribe to the idea that reminiscence is important for the regulation of development across the lifespan. As theories of psychological processes, they also share the assumption that mental health is an important outcome of developmental regulation. Although there is no simple one-to-one match between lifespan processes and the various functions of reminiscence, the mentioned correspondences shed light on the mental health outcomes of different forms of reminiscence. We concluded in the previous section that the social functions of conversation and teaching/informing are not strongly related to mental health, with the exception of an association with happiness. These functions of reminiscence correspond most closely to the processes described in socio-emotional selectivity theory, at least when they result in the recall of positive memories. Continuity and control theory both show more correspondence with the other uses of reminiscence: bitterness revival, boredom reduction, problem solving, identity, death preparation, and intimacy maintenance. The three dysfunctional ways of reminiscing (bitterness revival, boredom reduction, and intimacy maintenance) appear to be related to a feeling of continuity with the past that results in a negative evaluation of the present. This demonstrates that in some cases, continuity, which people generally prefer, may have negative corollaries.

Control theory makes clear that in these cases, individuals have to be willing to accept changes in the self using secondary control strategies. The functions of identity, problem solving and death preparation have in common that they deal not only with positive memories, but may activate a secondary control strategy to find meaning in past adversities. Through a process of integration of the negative memories, or a process of recalling how one coped with past problems, these are forms of reminiscence during which memories are evaluated and elaborated. Reminiscence thus involves balancing the maintenance of the structure of the self-system (continuity and primary control) with openness to change (secondary control; see also Westerhof Reference Westerhof, Hartung and Maierhofer2009). Compared to other descriptions of the life-review process, this balancing is close to the process of working towards integration. Coleman (Reference Coleman1986) made clear that not all people engage in this process of life review, but that it can be stimulated in interventions, a topic to which we turn now.

Reminiscence interventions

Studies of reminiscence as a naturally occurring process have paved the way for reminiscence as an intervention. We have seen that reminiscence is voluntary and partly reconstructive, and that particular styles of reminiscence associate with mental health outcomes. Stimulating the positive functions of reminiscence and discouraging the negative functions might help improve mental health in later life. Butler (Reference Butler1974) was among the first to promote life review as an intervention for this purpose. In the first wave of reminiscence research that followed Butler's work until around 1990, interventions were developed in many settings and for many target groups, including community residents (Fallot Reference Fallot1980; Fry Reference Fry1983), nursing home residents (Haight Reference Haight1988), and patients with dementia (Goldwasser, Auerbach and Harkins Reference Goldwasser, Auerbach and Harkins1987). Reviews of that research found limited evidence for the effectiveness of these reminiscence interventions (Kovach Reference Kovach1990; Molinari and Reichlin Reference Molinari and Reichlin1984; Thornton and Brotchie Reference Thornton and Brotchie1987). Some researchers realised that reminiscence is a more complex intervention than originally thought (Kovach Reference Kovach1990; Webster Reference Webster1994). The diversity and complexity of reminiscence is still a major challenge, but also one of its main attractions for both professionals and researchers (Gibson Reference Gibson2004).

The use of reminiscence and life review in interventions and therapies for older adults is very widespread nowadays, and there have been many different target groups, including: community residents, family members, voluntary aids, persons with chronic illness, persons with mental illness, rural-dwelling older adults, lesbian and gay older persons, war veterans, migrants, and ethnic minorities. The included activities have also been diverse, from autobiographical writing, storytelling, instructing younger generations about past events, oral history interviews, scrapbooks, artistic expressions, family genealogy, to blogging and other internet applications. Reminiscence programmes are used in neighbourhoods, higher education, primary schools, museums, theatres, churches, voluntary organisations, assisted-living communities, nursing homes, dementia care, and mental health institutions. It is hard to compile figures on the use of reminiscence, because interventions have been given different names, are used in disparate settings and are often part of other approaches. It is known, however, that about two-thirds of Dutch mental health institutions offer life-review interventions.

It has been argued that reminiscence interventions should make use of the research findings and scientific theories that link psychological processes in reminiscence to outcomes (Bluck and Levine Reference Bluck and Levine1998; Goldfried and Wolfe Reference Haight1996), and that they should take account of the characteristics of the target group (e.g. the level of psychological distress and context), the goals of the intervention, the skills of the counsellors, and developmental theories (Lin, Dai and Hwang Reference Lin, Dai and Hwang2005). We propose that the recently developed understanding of the various functions of reminiscence and their associations with mental health and lifespan processes provides a stronger evidence base and more appropriate theories with which to inform the design and delivery of interventions. Many scholars have distinguished simple reminiscence and life review (e.g. Fry Reference Fry1983; Haight and Dias Reference Haight and Dias1992; Webster and Young Reference Webster and Young1988), but recently a further distinction has been proposed between ‘life review’ and ‘life-review therapy’ (Cappeliez Reference Cappeliez, Webster and Haight2002; Garland and Garland Reference Garland and Garland2001). The principal difference between these two interventions is the amount of structure that is provided, which becomes clear when their purposes are considered. In interventions, simple reminiscence corresponds most closely to the instigation of social reminiscence, life review to the promotion of positive functions, and life-review therapy to the discouragement of negative types of reminiscence. The next paragraphs are short descriptions of the three types of interventions, with a focus on the various target groups, goals and activities, and on the skills required of the counsellors.

Three types of reminiscence interventions

Simple reminiscence is appropriate for older adults in relatively good mental health and who find sharing autobiographical memories a meaningful activity. The main mental health goal of simple reminiscence is to enhance positive feelings. A common application is reminiscence groups in nursing homes, during which prompts for positive memories are given (seeCook Reference Cook1991) and a more recent application is found in groups fostering intergenerational bonding (seeVan Kordelaar et al. Reference Van Kordelaar, Vlak, Kuin and Westerhof2008). The central activity is positive autobiographic storytelling that activates the social functions of reminiscence. The staff or counsellors need basic skills in facilitating the process of spontaneous reminiscence and promoting social interaction.

Life review is most suited to people who are struggling to find meaning in life or have difficulties coping with transitions or adversity in their lives. The goal of life review is to enhance aspects of mental health, such as self-acceptance, mastery and meaning in life (Birren and Cochran Reference Birren and Cochran2001; Bluck and Levine Reference Bluck and Levine1998; Wong Reference Wong, Haight and Webster1995), by stimulating the reminiscence functions of identity construction and problem solving (and possibly death preparation). Individual life-review interviews (Haight Reference Haight1988) and guided autobiography groups (Birren and Cochran Reference Birren and Cochran2001) are examples. The activities are structured in the sense that they focus systematically on the entire lifespan and promote the evaluation and integration of positive and negative memories (Haight and Dias Reference Haight and Dias1992; Webster and Young Reference Webster and Young1988). Life review helps people gain insights into how they have developed throughout their lives and have become the person they are now, which helps them recognise and express what they have learnt from their positive and negative experiences, and to recall the coping repertoire and values that have guided them in their lives. The counsellors need advanced skills, as in structuring the sessions and in framing the questions that link memories to current life situations, and to help the participants reconceptualise the meaning of past events.

Life-review therapy is mostly used in therapeutic settings for older people with serious mental health problems such as depression or anxiety. The goals are to induce self-change and alleviate the symptoms of mental illness. The focus is to reduce bitterness revival and boredom and to stimulate the positive functions of reminiscence. This requires a more dynamic intervention, because reminiscence by a mentally ill person normally prompts life-stories that evoke bitterness or dissatisfaction with his or her current self and life. Intervention protocols must be explicit about the way in which these life-stories are directed towards a more positive self-identity. One approach has been to link life review to theories of autobiographic memory in depressed people, in particular to focus on the specific positive memories which depressed individuals find it difficult to enlist in everyday life (Serrano et al. Reference Serrano, Latorre, Gatz and Montanes2004). Another approach has been to link life review with other therapeutic frameworks, e.g. psycho-analytic therapy (Fry Reference Fry1983), cognitive behavioural therapy (Cappeliez Reference Cappeliez, Webster and Haight2002; Watt and Cappeliez Reference Watt and Cappeliez2000), and narrative therapy (Bohlmeijer et al. Reference Bohlmeijer, Westerhof and Emmerik-de Jong2008). When life review is linked with other therapeutic approaches, counsellors need specialist skills and the knowledge of the other therapies.

The effectiveness of reminiscence interventions

An important question is how effective are these different types of interventions in relation to their goals. Although reviews of the first wave of reminiscence interventions found that the evidence base was still thin (Kovach Reference Kovach1990; Molinari and Reichlin Reference Molinari and Reichlin1984; Thornton and Brotchie Reference Thornton and Brotchie1987), the situation has improved in recent years. Recent reviews (Lin, Dai and Hwang Reference Lin, Dai and Hwang2005) and meta-analyses (Bohlmeijer et al. Reference Bohlmeijer, Roemer, Cuijpers and Smit2007; Bohlmeijer, Smit and Cuijpers Reference Bohlmeijer, Smit and Cuijpers2003; Hsieh and Wang Reference Hsieh and Wang2003) have shown that reminiscence interventions can be effective in improving wellbeing and alleviating depression. The particular application in dementia care has also been found effective in promoting wellbeing and mental health (Moos and Björn Reference Moos and Björn2006; Woods et al. Reference Woods, Spector, Jones, Orrell and Davies2005). All meta-analytic studies have concluded, however, that the effects of interventions are heterogeneous: only some are effective, which is not surprising given the diverse goals and target groups.

The evidence base for the effects of simple reminiscence is the thinnest: only a few studies have shown an effect on mental health (Bohlmeijer, Smit and Cuijpers Reference Bohlmeijer, Smit and Cuijpers2003; Bohlmeijer et al. Reference Bohlmeijer, Roemer, Cuijpers and Smit2007). Life review, however, does appear to have effects for wellbeing (Arkoff, Meredith and Dubanoski Reference Arkoff, Meredith and Dubanoski2004) and meaning in life (Westerhof, Bohlmeijer and Valenkamp Reference Westerhof, Bohlmeijer and Valenkamp2005), but less on depression (e.g. Hanaoka and Okamura Reference Hanaoka and Okamura2004; Haight, Michel and Hendrix Reference Haight, Michel and Hendrix1998). Only life-review therapy is effective in alleviating depression. On the basis of five recent studies (Arean et al. Reference Arean, Perri, Nezu and Schein1993; Goldwasser, Auerbach and Harkins Reference Goldwasser, Auerbach and Harkins1987; Klausner et al. Reference Klausner, Clarkin, Spielman, Pupo, Abrams and Alexopoulos1998; Serrano et al. Reference Serrano, Latorre, Gatz and Montanes2004; Watt and Cappeliez Reference Watt and Cappeliez2000), Scogin et al. (Reference Scogin, Welsh, Hanson, Stump and Coates2005) came to the conclusion that life-review therapy is an evidence-based intervention for depression in older adults, but different formats were used in the reviewed studies and the samples were relatively small. The evidence base requires strengthening through further independent trials.

When the findings of effect studies are related to the goals and methods of the different reminiscence interventions, it becomes clear that not all interventions have the same effects. Simple reminiscence is directed towards happiness, life review towards aspects of psychological wellbeing such as meaning in life and mastery, and only life-review therapy seeks to alleviate depression. The classification into three types of reminiscence interventions with different goals and methods emphasises that they do not have identical effects, and that their effectiveness should be studied in relation to their goals.

Discussion

Reviews of the early reminiscence research (Kovach Reference Kovach1990; Molinari and Reichlin Reference Molinari and Reichlin1984; Thornton and Brotchie Reference Thornton and Brotchie1987; Webster Reference Webster1994) concluded that there is a need for more precise definitions and measurements, and for better effect studies of interventions. This paper has reviewed developments in theory, research and practical applications over the last two decades, and found that the field has come a long way in dealing with its challenges. A better definition has been articulated and different functions of reminiscence have been empirically validated. There is increasing understanding of how the functions of reminiscence relate to mental health outcomes and to lifespan processes. The reminiscence interventions that have been used in recent effectiveness studies have had stronger theoretical and empirical foundations than seen before.

We have proposed that in relation to their functions for promoting mental health, there are three different types of reminiscence: positive reminiscence (identity construction, problem solving, and death preparation), dysfunctional reminiscence (bitterness revival, boredom reduction, and intimacy maintenance), and social reminiscence (conversation and teaching or informing). The differentiation is underpinned by theories of reminiscence, autobiographical memory, and lifespan development processes. It could be validated in factor analytic studies as well as by the differential relations of these three functions with mental health. Last, the threefold classification provides a way of classifying reminiscence interventions by their different uses of reminiscence functions.

We also believe that the proposed classification of reminiscence functions in relation to mental health points to several constructive directions for future research and practice development. First of all, studies of reminiscence functions will profit from a more person-centred approach. Studies on the relationship between reminiscence functions and personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status or personality are still few, and there are none on the best combinations of reminiscence types for an individual person. For example, intimacy maintenance might have a different form when combined with boredom reduction than when combined with identity construction.

Second, we need longitudinal studies of reminiscence and mental health. As we have seen, almost all published studies have been cross-sectional, so we know little about change over time in an individual's reminiscence functions. While the age differences found in cross-sectional studies suggest that the uses of reminiscence change over time, from more self-focused to more other-focused applications, this might be a cohort effect related to spreading individualisation (Timmer, Westerhof and Dittmann-Kohli Reference Timmer, Westerhof and Dittmann-Kohli2005). Longitudinal studies should also make clear under which conditions the uses of reminiscence might change. The lifespan theories discussed in this review have all made the assumption that reminiscence intensifies when individuals experience life transitions or a growing awareness of life's finitude, but the literature on contextual influences on different types of reminiscence is still sparse. Longitudinal studies will also provide more understanding of how different types of reminiscence and mental health mutually influence each other. Addressing these questions will improve our understanding of reminiscence and its uses across the lifespan, and more empirical evidence will further inform psychological practice. Clearly, more studies (particularly replications of earlier studies and controlled trials with large samples) are needed to test the effectiveness and efficacy of interventions. The threefold classification of different types of reminiscence intervention can be used to guide the development of reminiscence interventions as well as evaluations of their effectiveness.

Interventions would profit further if studies of reminiscence interventions included measures of their use and outcomes. First, evidence about whether or not an intervention changed the reminiscence functions would be of interest. Second, it should be more widely understood that people disposed to a particular use of reminiscence profit to a greater or lesser extent from different interventions, and all practitioners should know that interventions can have negative side-effects, such as increased worry or rumination for persons with a negative type of reminiscence. Third, studies of the actual use of reminiscence by the participants during interventions would provide further information on the processes which lead to changes in mental health. To conclude, although there has been much progress in the last two decades, much challenging and important research is still required in this intriguing field of study.