Introduction

The move by older people into residential accommodation is often seen as perilous, because the residents’ uprooting from their former home is regarded as a potential threat to the older person's identity, happiness and quality of life (Rowles, Reference Rowles1983; Ryvicker, Reference Ryvicker2009; Stones and Gullifer, Reference Stones and Gullifer2016). Consequently, residential homes (including care homes and nursing homes) try to support residents in ‘place-making’, so that residents develop a sense of belonging in the new environment and come to feel ‘at home’. Two elements which are regarded as important in supporting residents to ‘become at home’ in residential accommodation are having familiar material surroundings and meaningful social relationships. While both of these have received significant attention, they have largely been treated in isolation to each other. In particular, the capacity for material culture to help in the formation of new relationships in residential homes has been overlooked. In this paper, I present findings from qualitative research in an older people's home which demonstrate that interactions with material culture can help residents to not only maintain existing social ties, but also form new meaningful relationships with other residents and members of staff.

Objects reflect and constitute people's sense of who they are, acting as ‘material companions’, acquiring ‘meaning and value by sheer dint of their constancy in a life’ (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Reference Kirshenblatt-Gimblett and Oring1989: 330). It is unsurprising then, that on moving into residential accommodation older people – or more often their family members – typically select possessions to take with them from their former home. Previous studies in minority world settings suggest that furnishing their rooms in residential homes with familiar belongings can help residents to feel a sense of home (Wada et al., Reference Wada, Canham, Battersby, Sixsmith, Woolrych, Fang and Sixsmith2020) and ‘successfully transition’ into the residential environment (Sherman and Newman, Reference Sherman and Newman1978) by giving them a sense of control (Paton and Cram, Reference Paton and Cram1992) and supporting them in maintaining a coherent sense of identity at a time when it is perceived to be under threat (Wapner et al., Reference Wapner, Demick and Redondo1990). Correspondingly, research suggests that some residents regret the loss of their meaningful belongings, and that this can hinder their ability to feel at home in the institution (Johnson and Bibbo, Reference Johnson and Bibbo2014). These studies emphasise the role of objects in ‘identity maintenance’, implying that older people's sense of self is predominantly derived from past events, accomplishments and relationships that can effectively be stored, represented or embodied in things. Research has also demonstrated how objects enable residents to accomplish meaningful everyday activities in the present (Nord, Reference Nord2013), and how changes to rooms and the acquisition of new items reflect future aspirations and the ongoing dynamism of identity (Lovatt, Reference Lovatt2018). While this literature is helpful in showing how material culture can help residents to develop a sense of place in the new environment, it focuses on individual residents and their possessions in place-making. This reflects Cathrine Degnen's observation that much of the literature on place-attachment in older age has emphasised this as an individual process of belonging between an older person and their home, overlooking the ways in which ‘relations with and through place are not only personal – they are powerfully social’ (Degnen, Reference Degnen2016: 1648).

Meaningful relationships in later life are important to mental and physical health (Bennett, Reference Bennett2002; Vanderhorst, Reference Vanderhorst2005). The move into long-term residential accommodation is perceived as threatening to older people's relationships, because of the challenges it can pose to maintaining existing social networks (Parmenter et al., Reference Parmenter, Cruickshank and Hussain2012; Stones and Gullifer, Reference Stones and Gullifer2016). Research has identified loneliness as a problem among care home residents (Nyqvist et al., Reference Nyqvist, Cattan and Andersson2013; Paque et al., Reference Paque, Bastiaens, Van Bogaert and Dilles2018; Barbosa Neves et al., Reference Barbosa Neves, Sanders and Kokanovic2019) and a number of studies from different countries have found that increasing social interaction can enhance the quality of life and wellbeing of residents (Willcocks et al., Reference Willcocks, Peace and Kellaher1987; Higgins, Reference Higgins, Allan and Crow1989; Reed and Roskell, Reference Reed and Roskell1997; Hubbard et al., Reference Hubbard, Tester and Downs2003; Drageset, Reference Drageset2004; Bergland and Kirkevold, Reference Bergland and Kirkevold2008). In order to reduce the risk of loneliness and associated negative impacts on quality of life, there is therefore a need to identify strategies that support residents of older people's homes to maintain existing personal and social relationships, and foster new ones. In terms of existing relationships, family members can continue to care for residents and support them in making decisions in institutional settings (Bowers, Reference Bowers1988; Zarit and Whitlatch, Reference Zarit and Whitlatch1992; Rowles High, Reference Rowles, High and Stafford2003). Staff members can help residents to maintain friendships with people outside the home (Cook, Reference Cook2006) and can also facilitate friendships between residents, either through formal activity sessions or everyday interactions, although low staffing resources can affect the amount of time staff have to spend with residents, which can hinder residents’ ability to feel at home (Wada et al., Reference Wada, Canham, Battersby, Sixsmith, Woolrych, Fang and Sixsmith2020). Studies have also identified that the built design of residential homes can influence residents’ social relationships, for instance through accessible design allowing residents to move between private and public spaces (Barnes, Reference Barnes2003). However, less attention has been paid to how residents’ own belongings can impact on the maintenance and development of social relationships.

It is surprising that the literatures on material culture and relationships in older people's residential care have developed largely separately from each other, given the substantial literature on how meaningful relationships are made, reinforced and negotiated through the display, gifting, disposition and bequeathing of things (Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton, Reference Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton1981; Finch and Mason, Reference Finch and Mason2000; Price et al., Reference Price, Arnould and Curasi2000; Marcoux, Reference Marcoux and Miller2001; Finch, Reference Finch2007; Miller and Parrott, Reference Miller and Parrott2009; Hurdley, Reference Hurdley2013; Newson, Reference Newson2018). Our relationships with people take place within, and are shaped by, a material environment. The objects that surround us take on new meanings, beyond the function for which they were originally designed, based on their associations with the people in our lives. Decisions about what we do with objects then, e.g. what we should keep, what we should give away, to whom should we gift things, are informed by memories and emotions as well as more practical considerations. Studies of disposition and inheritance practices suggest that objects can be regarded by bequeathers and inheritors as symbols or embodiments of people and relationships (Price et al., Reference Price, Arnould and Curasi2000; Richardson, Reference Richardson2014; Lovatt, Reference Lovatt2015). This entanglement of objects and people has been conceptualised as a process whereby boundaries between people and things become ‘destabilised’, ‘such that material objects can become extensions of the body and therefore of personhood’ (Hallam and Hockey, Reference Hallam and Hockey2001: 43).

Several studies have found that residents of older people's homes value their possessions for their capacity to symbolise past or existing relationships, where the sheer presence of the object is a comforting reminder of the resident's life with a spouse or family (Wapner et al., Reference Wapner, Demick and Redondo1990; Paton and Cram, Reference Paton and Cram1992; Nord, Reference Nord2013). Less attention has been paid to how existing relationships are reinforced through ongoing interactions with objects, and to the ways in which objects can help to construct new relationships. Research conducted in residential care settings for children has found that the gifting of objects can create and reinforce emotional ties between children and adult members of staff (Emond, Reference Emond2016). I suggest that the lack of comparable research in older people's residential settings into how objects can facilitate social interaction reflects dominant assumptions that older people are predominantly past oriented and have limited capacity to use objects to form new social relationships. I have argued elsewhere that this assumption is reflected in research that focuses on how material culture can help older people maintain their identities on moving into residential care, but overlooks how residents’ interactions with their possessions reveals an ongoing construction of the self and future intentions (Lovatt, Reference Lovatt2018). It is as though after a certain age, the future is regarded as irrelevant. This past-oriented view of selfhood in older age is at odds with social scientific conceptualisations of identity as fluid and multi-temporal, whereby a person's sense of who they are is informed by memories of the past, present actions, and thoughts of the future (Laceulle and Baars, Reference Laceulle and Baars2014). Similarly, it underemphasises identity construction as a necessarily social project, where a person's sense of self is always informed by interactions with other people – in the present and future, as well as the past (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2008).

In order to understand how residents’ interactions with their belongings can help to reinforce existing relationships and construct new ones, it is helpful to draw on the theoretical approaches of relationality, social practices and material culture studies. These consider how people's social interactions and relationships are necessarily mediated through material environments and materially mediated practices such as gifting (Smart, Reference Smart2007; Miller, Reference Miller2009). Drawing on Morgan's work on family practices, which emphasises how relationships are done rather than are, a relational practice approach allows us to see the activities people engage in to sustain – or indeed undermine – relationships (e.g. by deciding whether or not to give a birthday present to someone) (Finch and Mason, Reference Finch and Mason2000; Morgan, Reference Morgan2011). Further, relationality highlights how meaningful relationships are not necessarily located in the kinship structures of ‘mother’, ‘daughter’ and so on, but can occur between people who relate to each other in other ways (Carsten, Reference Carsten2004). In this way, relational approaches allow for the possibility of change in how people relate to each other, as well as for the formation of new relationships. By widening attention from family relationships, which have traditionally been the focus of kinship studies and research into older people and material culture, to other meaningful social interactions which take place between people, such as friends or acquaintances (Heaphy and Davies, Reference Heaphy and Davies2012), we can better understand how residents may form new meaningful relationships with each other, and with members of staff.

In this paper, I present findings from a qualitative study in an older people's residential home that demonstrates how interactions with material culture helped residents to form new meaningful relationships with staff members and other residents, as well as maintaining existing relationships.

Methodology

The findings presented here are derived from data collected as part of a research project that aimed to explore how older people in residential homes experience a sense of home (or not) through their everyday interactions with their material surroundings. The project received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Sheffield. I was interested in the choices residents made about how to furnish their rooms on initially moving into the home (and, in the case of many residents, the choices that were made on their behalf by family members) but also how their ongoing, mundane interactions with things shaped their everyday experiences of life in the home. My research design comprised an ethnographic approach that combined in-depth interviews with residents, informal conversations with residents and staff, and observations of daily life in the home. This design elicited data on the meanings particular objects had for residents, and how residents’ relationships and social interactions were mediated by material culture.

I conducted fieldwork in The Cedars, a residential home located in a city in northern England.Footnote 1 Run by a not-for-profit care provider, it provides support to over 40 residents in a purpose-built home. Each resident has their own room – similarly sized and designed – which comprises a combined living and bedroom area with en-suite bathroom. The Cedars does not provide nursing care, and while many residents at the time of my fieldwork had chronic health conditions and needed help with bathing and getting dressed, the majority were in reasonably good health. Typical circumstances which prompted the move into the home included declining health, loneliness following bereavement and distance from family members. While some residents had dementia, I did not include them as participants in my research, and only included residents who I judged to be capable of providing informed consent. For more details of The Cedars, see Lovatt (Reference Lovatt2018). I conducted fieldwork there between July 2012 and June 2013, typically visiting the home twice a week. I spent the first visits familiarising myself with life in the home, introducing myself to the staff and residents, explaining my research and identifying which residents were interested in taking part in in-depth interviews.

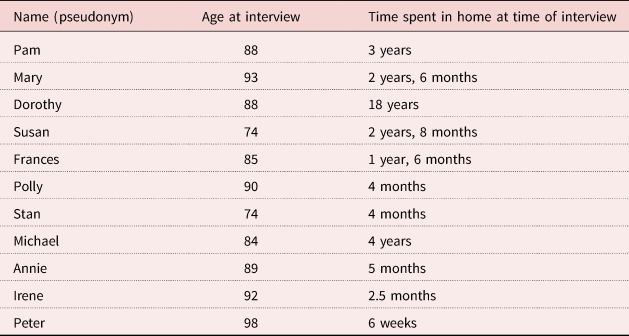

During my visits over the course of the 12 months, I chatted to residents and staff members, took part in activity sessions, and got a sense of the routines and atmosphere in the home. While I was particularly interested in observing how residents and staff members interacted with the materiality of the home, and how, where, when and with whom they spent their time, in seeking to get a sense of the overall culture of the home I noted everything that occurred to me during my visits. I typed up observations and reflections as field notes as soon as possible after each visit. With residents’ consent I took photographs of some objects and room layouts, in order to aid my understanding of the meanings particular belongings had for residents, and how their daily lives were shaped by their material environment. I also conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with 11 residents (for details of participants, see Table 1). Interviews took place in residents’ rooms and lasted between 40 minutes and one hour. Interview topics included: the circumstances in which they moved into the home, the objects they had brought with them, the conversations they had with staff or other residents about their belongings, the changes they had made to their rooms over time, their everyday lives in The Cedars, and how they felt about living there. I audio-recorded the interviews and transcribed them verbatim. I adopted a thematic narrative analytical approach that enabled me to identify the key themes from my ethnographic research, without losing a sense of the individual stories of the residents (Riessman, Reference Riessman2008). This was important, as the stories the residents told about the objects in their room only made sense within the context of their lives. I began by inductively coding the field notes and interview transcripts together, using NVivo 10 software, and then grouped the codes into overarching themes (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). While this process resulted in themes that were applicable across the data-set, as part of my analysis I contextualised the themes within the individual circumstances of each resident, using my observations of them and the narratives they told in their interviews. This helped me to interpret how and why themes such as ‘becoming at home’ were experienced differently by different residents.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants

Prior to beginning fieldwork, I had expected that the material culture of residents’ rooms would influence social interactions but I had not anticipated the extent to which my research would identify how objects shaped existing and new social relationships. During analysis I conceptualised codes such as ‘gifting’, ‘bequeathing’, ‘displaying’ and ‘circulation of objects within home’ as relating to an overarching theme of relationships. I then reviewed the data from my field notes and interview transcripts though the conceptual lens of ‘relationships’ and refined this theme by identifying how the gifting, bequeathing, etc., of belongings influenced residents’ relationships with different groups of people (e.g. with family, with other residents, with staff members). In the following section, I present findings that demonstrate how material culture influenced residents’ relationships; an important element of residents’ everyday experiences of living in the home.

Findings and analysis

Material culture in residents’ rooms embodied and evoked previous and existing relationships (e.g. with spouses and children), but more unexpectedly facilitated and reflected new relationships in the home. Objects circulated, were gifted and inherited, and formed part of the webs of meaning and connectedness that developed between residents, and between residents and staff members. The following section is structured to reflect how social interactions with material culture influenced residents’ relationships with three groups of people: (a) relationships between residents and family outside the residential home; (b) relationships between residents in The Cedars; and (c) relationships between residents and staff members in The Cedars. Interwoven through each of these three themes is analysis of the meanings, emotions, obligations, ambivalences and complications that are revealed through observing materially mediated social interactions.

How material culture helped residents to maintain existing social ties with family

Nearly all of the residents had family members living nearby who visited frequently. Through conversations with residents and staff members I built up a picture of each resident's relational network, in terms of who mattered to them. Very often anecdotes about visitors would either prompt, or be prompted by, references to the material culture of residents’ rooms. The family relationships were reflected and reinforced in the gifting and display of material possessions, and these manifested in several ways: family members taking ownership of, or looking after valued possessions which the residents could not take with them on entering the residential home; gifts between the residents and their families and the residents’ display of these; and plans made by the resident to bequeath certain items to family members after they died.

All of the residents spoke of being unable to take all of their possessions with them on moving into the residential home. Several residents told me that while they had found it difficult to leave certain things behind, they felt much better when relatives were able to keep items, as it comforted them that objects which had been meaningful to them were kept in the family, a finding reported in previous studies of household disbandment (Ekerdt et al., Reference Ekerdt, Luborsky and Lysack2012; Mansvelt, Reference Mansvelt2012). For some residents, their move into The Cedars had coincided with grandchildren setting up home, or other family members’ changing circumstances, which resulted in practical items such as white goods and kitchen equipment being kept within the family and put to good use. At a time in the residents’ lives when they might have been feeling particularly vulnerable and dependent, it is possible that they appreciated this opportunity to be able to help out younger family members and ‘be useful’. Annie was able to give most of her furniture to her grandson, which gave her peace of mind at not having to worry about what was going to happen to it:

because I was fortunate, well, fortunate or unfortunate [depending on] the way you look at it. My grandson had just been separated from his wife and he'd got a flat and no furniture, so everything went straight, he had a full home. It went straight across to him so I had no worries about it being moved, or you know, where it was going or anything, so I was quite lucky in that respect.

Family members also provided safe-keeping for expensive items such as jewellery, which the residents did not want to risk keeping themselves, and items such as photograph albums which residents might not have space for in their room, but which they still wanted to see. In this way, despite the residents’ move to the residential home, they did not necessarily become more isolated from family members and material culture played a key part in reinforcing family ties.

Family members also added to the material culture of residents’ rooms through new gifts. Following Morgan's (Reference Morgan1996) concept of ‘doing family’, such actions worked to affirm that the resident was still part of the family, despite their conceptual move from ‘the community’ to ‘an institution’. Similarly, residents’ display of items given to them by family members demonstrated to observers that the resident was still an active member of a family. ‘Displaying families’, a concept developed by Janet Finch, is the ‘process by which individuals, and groups of individuals, convey to each other and to relevant audiences that certain of their actions do constitute ‘doing family things’ and thereby confirm that these relationships are ‘family relationships’ (Finch, Reference Finch2007: 67). ‘Relevant audiences’ in this context included fellow residents, staff members and visitors such as myself, and I interpreted residents’ enthusiasm to point out new gifts to be a way of demonstrating that they still mattered to the people who mattered to them. Frances, for instance, told me that a framed picture on her wall had been given to her that year by her daughter on Mother's Day, thereby emphasising and reinforcing the familial relationship.

Residents found homes for new gifts in amongst the existing materiality of their rooms. Pam was 88 and had lived in The Cedars for three years. She had a son with learning difficulties who lived in supported accommodation. On one occasion when he visited Pam with his carer, he brought a present of a flower made out of pipe cleaners and card which he had made during a craft session. Pam placed it amongst ornaments which she had brought with her when she first moved into the residential home, and when she pointed it out to me she told me that her son had come in with it saying, ‘it won't need much water!’

Not all gifts from family members were necessarily valued for what they were, but were displayed more out of obligation, or for fear of offending the person who had given it to them. On one occasion when I visited Irene, I commented on a child's drawing that was stuck to the wall. Irene grimaced: ‘it's revolting, but as the grandchildren gave it to me I suppose I've got to put it up!’ This is reminiscent of the participant in Rachel Hurdley's study of mantelpieces who felt obliged to display a small lump of hard dough – which she described as an ‘aesthetic monstrosity’ – because it was a gift from her young grandson (Hurdley, Reference Hurdley2006: 725). Contrastingly, Pam deliberately chose not to display certain photographs so as to avoid potential offence. She had a large family with many great-grandchildren, and rather than run the risk of not displaying everyone's photograph in a suitably prominent position, she decided to display hardly any at all, telling me, ‘well you've got to be careful haven't you really? I mean you can soon cause offence!’ This shows how family ties can be reinforced by things that are not displayed, as well as by things that are.

As many of the residents had difficulty walking and so did not often leave The Cedars, it was not always straightforward for them to buy gifts for family and friends for birthdays and Christmas, particularly as the majority of residents did not have internet access. It was often easier to give money to another family member and ask them to buy a present on their behalf. However, before Christmas and sometimes in the summer, the staff would set out a table in the entrance foyer, displaying objects that had been donated by members of staff, given by residents and their families when they downsized and moved into the home, or donated by family members after a resident had died. Residents and visitors to the home could buy the objects for small amounts of money, which then went into a fund which was used by The Cedars to fund outings, or buy objects for residents who would not otherwise have been able to afford them. Residents could also buy Christmas cards, wrapping paper and decorations. When I visited one resident, Dorothy, in November 2012, she already had her Christmas tree up (which she kept underneath her bed during the rest of the year) and a mound of wrapped Christmas presents which she had bought from the stall. The stall and the residents’ use of it was an example of how The Cedars facilitated the circulation and movement of material culture in unexpected ways, such that the personal possessions of a recently deceased resident could become Christmas presents for the family members of other residents. This was similar to the arrangement in the day centre studied by Haim Hazan, which held jumble sales where attendees could discard their own things and buy objects that had belonged to other people. Hazan (Reference Hazan1980: 84) interpreted this as an act of ‘self-sufficiency and independence of the outside world’, further evidence of what he took to be the centre's ‘autonomous isolated character’. In The Cedars, however, the arrangement helped residents to maintain relationships with family members and arguably make any perceived boundaries between the ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ worlds less distinct.

Some residents had thought about what they wanted to happen to their belongings after they died, and divestment decisions were influenced by family relationships. Annie expected that her oldest son would take her collection of crystals, ‘[b] ecause he's very much, he thinks very much like I do, you know, and different things I've given him, especially collectable items, he's hung on to’. Susan's youngest son had requested her favourite clock, and she was happy for him to have this. As well as wanting to ensure that certain items went to particular family members, some residents were keen to arrange this while they were still alive as they did not want to ‘make any more work’ for their children after they had died. Mary, who was 93 and in poor health for much of the time that I knew her, was in the process of sorting out her cupboards as she did not want to ‘cause any trouble’ for anybody after she had died by failing to leave instructions as to what should be done with certain objects. Another motivation for doing this was to ensure that some things did not end up with particular members of the extended family. By working to ensure that certain valued items were inherited by particular family members and not others, Mary's divestment strategies actively constructed family relationships, echoing Finch and Mason's’ research on inheritance, which argued that divestment decisions do not just reflect family relationships, but actively construct them (Finch and Mason, Reference Finch and Mason2000).

How material culture facilitates relationships between residents

The relationships between residents were reflected, maintained and, in part, constituted by material culture and its movement within the home. Objects travelled between residents both as a result of gifts between living residents, but also as a consequence of residents dying and their possessions being offered to surviving residents with whom they had been friendly. Residents’ belongings also afforded the opportunity for friendships to develop between residents.

I did not encounter many instances of residents gifting objects to each other, but Susan – who was very popular – received presents from other residents on her corridor. When I visited her shortly after her 75th birthday she showed me the necklace and two pairs of earrings which had been given to her by a resident further down the corridor. On seeing these and other presents I told Susan that it showed that she was held in high regard, and she replied ‘it must do’. The close friendship between Susan and Annie was also realised in the gifting of presents. Susan had once remarked that her legs were cold, and Annie had responded by crocheting her a blanket. Annie had also made Susan two hats, and told me that she was trying to teach Susan how to crochet, although when I later asked Susan about this she laughed and said ‘I'm trying!’

Close relationships between residents were also acknowledged by staff, residents and family members when residents died and their rooms were cleared. Objects which were not wanted by surviving family members were sometimes offered by the families or staff members to residents who were thought to have been particularly close to the deceased person. Susan possessed some items which had previously belonged to now deceased residents with whom she had been close. When describing the objects, Susan spoke of the previous residents with warmth. For instance, Susan told me about a teddy bear she had inherited from a former resident:

Susan: She made me laugh, I used to laugh at her, she was so funny. But yet she was a very determined woman. And she was 103, and she'd still got it all up here [points to head] … But we had some laughs with her. You know my wheel – you know wheelchairs? … She used to get in one of them, and she used to come whizzing down this corridor, right through to the bottom!

Melanie: And how come she gave you the teddy bear?

Susan: Well she didn't give it me, it was her daughter. They were going to throw it away, I said ‘don't throw that teddy away’ … I've had him ever since. And he's a lovely teddy. My granddaughter … likes nursing him when she comes.

Similarly, Susan told me that she was given the china mugs on her dressing table by the family of the resident to whom they used to belong, and that the family still visited her.

In cases where it was left for the staff to sort through the rooms of residents who had died, they would sometimes offer items to residents who they knew had been particularly close to the deceased resident. Dorothy told me that a doll on her bed had once belonged to another resident:

One of the ladies that's died, when she died they asked me if I'd have it. Because she made it herself, you see. And she [staff member] said ‘would you want it? We don't want to throw it away’. So I said yes, because I knew her … so that's how I've got that one.

Both Susan and Dorothy emphasised that they knew the residents whose objects they now owned; this implied that their acceptance of the items was not purely down to wanting the object or not wanting it to be thrown away, but to how they felt about the resident to whom it had once belonged.

The material culture of residents’ rooms facilitated the development and maintenance of meaningful relationships between residents at The Cedars, often in ways that were so mundane and taken for granted that residents might not have been aware of them. For instance, one resident spent most afternoons in Susan's room sitting next to her in a chair, watching television, with a cup of tea placed on a table next to her. The television, chair and table which made these valued interactions possible ‘framed’ (Miller, Reference Miller2010: 50) the encounter without taking centre stage. One resident was aware of the potential for objects to facilitate relationships in a more obvious way. Peter told me that while he had never anticipated moving into a residential home, now that he was at The Cedars he saw it as an opportunity to meet new people, rather than as a symbolic ending of previous relationships. Peter told me that his priority was to find ways of socialising with fellow residents and was conscious of the opportunities for socialising which were afforded by his possessions and his interests. He wondered whether residents would be interested in talking to each other about the photographs in their rooms. Knowing of Peter's interest in photography, I put him in touch with another resident, Stan, who had recently bought a new camera and was struggling with learning how to use it.

How material culture facilitates relationships between residents and staff

Staff members were very important in the day-to-day lives of residents, and as well as relying on them for basic care, residents valued the friendly relationships they developed with the carers and cleaners, echoing other research which has found that staff and residents can become close (McGilton and Boscart, Reference McGilton and Boscart2007; Brown-Wilson and Davies, Reference Brown-Wilson and Davies2009). While some research has highlighted how differences and power imbalances between staff and residents in residential and nursing homes and supported living accommodation impact negatively on residents’ quality of life (Lee-Treweek, Reference Lee-Treweek1994; Kontos, Reference Kontos1998), I saw little evidence of this at The Cedars. Rather than acting in opposition to each other, I saw residents and carers expressing sympathy and solidarity with each other against issues from which they all suffered and were powerless to influence, such as the ongoing problems of the home being short-staffed. Further, this study suggests that the relationships between staff and residents went beyond the ‘functional with a focus on the task of care giving’ (Cook and Brown-Wilson, Reference Cook and Brown-Wilson2010: 28). Having a good relationship with staff was particularly important for residents who tended to spend most of their time in their rooms and did not eat in the communal rooms. I was initially surprised at how, despite apparently never leaving their rooms, they knew details about other residents’ lives, for instance if they had been ill. However, the residents told me that they used trusted members of staff to ask about each other, and to pass on messages, even if they thought that staff should not really do this. For instance, Mary told me:

[The staff] mustn't really tell you things … and you mustn't really talk. Justin [cleaner] and I, he tells me little things. ’Cause I say ‘how are the girls?’ ’Cause he knows if anybody's ill or back [from hospital]. And he will say. Now [about] Pam I say, ‘give her my, send my love’, so he, you know, that's little things we do and I write little notes.

On another occasion when I visited Mary I saw her pass a note on to one of the care assistants when she brought tea.

Like the relationships between residents, relationships between residents and staff members were manifest in the interaction with, and discussion, acquisition and gifting of, material culture. Michael moved into The Cedars during a period of ill-health. Having no close relatives nearby to help him with the move, Michael did not take many possessions into The Cedars with him and four years after the move, his room was still quite bare and sparsely furnished compared to other residents’ rooms. While he got along with other residents he chose not to socialise with them, but was very close to one of the senior carers, and could sometimes be seen sitting in a chair outside her office. This relationship was reciprocal, and she had given Michael some of her own furniture, such as a sofa and a cushion displaying the name of a local football team that they both supported. Other examples of staff members giving gifts to residents included a care assistant who bought Susan a fridge magnet as a souvenir following a trip to Poland to visit her family. Another care assistant was a skilled artist and cartoonist, and he made birthday cards for residents, and also donated one of his drawings as a prize for the Christmas raffle. This was won by Annie and she put the picture up on her wall.

Interactions between staff and residents about material culture occurred in other ways. Staff and residents would talk or share a joke about some of the things in residents’ rooms, such as the toy tiger in Frances’ room which had been given to her by her brother. In his customary spot by the radiator, the large tiger was immediately noticeable on entering the room. ‘I bet [the staff] ask you about the tiger as well, don't they?’, I asked Frances. ‘Ooh aye. When they first came in and saw him down [there] it half frightened ’em to death!’, she laughed. On my visits to residents, it was usual for members of staff to pop in, to offer tea or coffee, or to empty bins and do some cleaning. I therefore developed a sense of the usual routine interactions between residents and staff in the context of the residents’ rooms. Quite often, staff members would ask residents if a picture was new, or ask who had brought them flowers. As well as realising the potential for objects to facilitate relationships with other residents, Peter also used the things in his room to spark conversations with members of staff. He was particularly proud of the photographs that he had taken, which were now framed and displayed on his wall:

Melanie: What about staff members? Carers or cleaners? Do they comment on pictures, or –

Peter: Well partially I've taken the initiative myself, [by] saying ‘have you seen the fox? Do you know who took the photograph?’ So, I'm not shy!

Staff also sometimes helped residents to buy new items when it would have been difficult for them to do this themselves. Dorothy had chosen a new clock with the help of one of the senior carers, who had sat and gone through a catalogue with her until she found one she liked.

While most of the interactions with material culture contributed to or reflected positive relationships between staff and residents, they were sometimes the site of tension. For instance, staff monitored some residents’ accumulation of possessions, particularly in the case of residents whose families did not visit them as frequently or take an active role in sorting out clutter and piles of newspapers. Half fondly, half despairingly, one carer told me about the challenges they faced with persuading some residents to get rid of things: ‘“why won't you throw that away, it's broken?” “Yes, but I've had it 18 years”’. I witnessed one incident where a care assistant appeared to transgress what the resident judged to be appropriate behaviour towards her possessions and privacy. Shortly after her 75th birthday, Susan showed me some of her presents, which included a pink box given to her by her son which contained gourmet delicatessen foods. As we were talking, a care assistant, Nicola walked in. My interpretation of what happened next is recorded in my field notes:

Nicola walks in, says hello, heads straight for the pink box on the chest of drawers and looks inside. I am a little taken aback at her presumption, and wonder how Susan will react. ‘You're very nosy, you’, says Susan, and I can tell she is annoyed. Without being invited, Nicola then sits down on the bed … ‘We were actually having a private conversation’, says Susan, and ‘you're not welcome’. Nicola leaves, and Susan tells me that this is not the first time she has told Nicola off for looking at her things without being asked. Susan says Nicola goes through her drawers, opens her cupboards, and whenever Susan gets something new or comes back with shopping, Nicola will start to go through it or ask what she's got. Susan clearly has no qualms about telling Nicola to stop it, but there are many residents who would not be able to do this.

Not long after Susan dismissed Nicola, a different senior carer came into the room and she and Susan chatted for a few minutes. Susan then invited the carer to look in the box and told her that it was a birthday gift from her son. The contrast with the encounter with Nicola was striking. Susan gave short shrift to a staff member who she (and I) felt was rude and presumptuous, while she was quite happy to welcome another member of staff who did not act inappropriately around Susan's personal belongings.

Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, I have shown how material culture helped residents of The Cedars to maintain existing relationships with family and friends, and also to form new social relationships within the residential home, with other residents and members of staff. All of these relationships were reflected in, and constituted by, interactions with material culture. Sometimes residents used objects in a conscious, deliberate way in their social interactions, e.g. by gifting items to, or displaying items from, people who mattered to them. Other social interactions, such as residents watching television together, were made possible through taken-for-granted arrangements of furniture. Such activities were not as obvious as gift-giving in creating or reinforcing friendships, but were crucial in providing opportunities for everyday conversation and a sense of familiarity and belonging in the home. Furthermore, material culture did not necessarily stay within individual residents’ own rooms, but circulated as gifts and bequests. These findings extend knowledge on the significance of material culture in older people's residential homes by demonstrating that objects are not just static, passive, symbolic representations of relationships, but actively reinforce and create them.

Conceptualising the agency of objects in this way coheres with approaches from different disciplinary traditions on the significance of materiality, or the non-human, within people's lives. Researchers from material culture studies have argued that objects do not simply passively store aspects of people's identity but actively shape them (Miller, Reference Miller2010; Kidron, Reference Kidron2012) and socio-material approaches consider how materials and environments do not just provide a ‘context’ for human behaviour, but ‘human and non-human actors configure into assemblages that are the complex and emergent outcomes of the interactions of people, technologies, systems, and ideas’ (McDougall et al., Reference McDougall, Kinsella, Goldszmidt, Harkness and Strachan2018: 220). Emerging inter-disciplinary work on ‘materialities of care’, which focuses on the ways in which materials intersect with care work in a range of health and social care settings, emphasises the processual, ongoing and dynamic practices and relations that characterise this work (Buse et al., Reference Buse, Martin and Nettleton2018). Despite the opportunities such approaches offer for better understanding the relationships between people and objects in the context of later life, few studies have taken this approach. Those that have, for instance Buse and Twigg's (Reference Buse and Twigg2016) research into the narratives told by people with dementia about their clothes and Chapman's (Reference Chapman2006) ‘new materialist’ approach to the interdependent relationship between older women and their belongings, have focused more on individuals and their possessions, rather than on material culture in the context of personal and social relationships in older age. That previous studies on material culture in older people's residential homes have focused more on how individual residents use personal belongings to maintain elements of their identity that are bound up with past or existing relationships, rather than explored the opportunities objects afford for developing new relationships, may reflect assumptions that older people are more oriented towards the past than they are to the present and future. While maintaining relationships is important, the ability to form new ones is also crucial, particularly following a move into the unfamiliar environment of a residential home.

The findings in this paper also show how close observations of the ways in which social relationships are mediated through the material world can illuminate relationships that matter to people. People relate meaningfully to all sorts of people to whom they might not be related or consider to be friends. That we do not have a conventional or convenient way of labelling all of these people does not mean that they do not matter to us. As Carol Smart (Reference Smart2007: 47) writes, ‘relatedness … takes as its starting point what matters to people and how their lives unfold in specific contexts and places’. In the specific context of The Cedars, I found that the objects with which residents furnished their rooms provided insights into what mattered to them, and importantly who mattered to them and why. The combination of observations with interviews and informal conversations was important in providing insight into these meanings. The relatively small number of family photographs in Pam's room compared to that of other residents could have been interpreted as an indication of Pam having a very small family, with whom she was not close. In fact conversations with Pam revealed the opposite to be true: her decision to limit the photographs she displayed came out of a concern to not offend members of her very large family who may have been disgruntled at their photograph not being displayed sufficiently prominently. This example demonstrates that decisions about displaying or not displaying objects did not just reflect residents’ relationships with individual family members, but indicates residents’ awareness of the complexities of family relationships that involve multiple members. Examination of the material culture of The Cedars revealed that fellow residents and members of staff mattered to residents. By taking a relational approach that was rooted in everyday social–material interactions, my research identified meaningful relationships that might otherwise have gone unrecognised. Recognising how positive relationships in care homes might be identified and supported is particularly important given that other studies have highlighted the often negative, oppositional relationships particularly between staff and residents in care home settings (Lee-Treweek, Reference Lee-Treweek1994; Kontos, Reference Kontos1998).

A number of implications for residential home practice arise from this study. The findings suggest that material culture can help to form social relationships between residents and staff, and therefore residential home managers could identify more opportunities where residents’ possessions could be used in this way. These could be as simple as encouraging cleaners and care assistants to take an active interest in residents’ belongings, or facilitating one-to-one or group sessions where residents could talk about their things to each other, thus providing the opportunity to learn more about shared interests. This echoes earlier studies that have suggested having ‘possession-oriented counselling groups’ to foster social interaction between residents (Wapner et al., Reference Wapner, Demick and Redondo1990). As well as taking an interest in particular objects, staff could also be aware of how more mundane objects such as televisions and chairs could be arranged in residents’ bedrooms and communal areas in order to encourage conversation and other companionable activities. Homes should also consider having regular jumble sales or similar events, in order to provide residents with the opportunity to buy gifts for family and friends, thereby helping them to reinforce valued relationships. The residents who participated in this study had lived at The Cedars for varying lengths of time, from less than two months to 18 years. My findings identify opportunities for staff to use object-focused conversations or activities to foster meaningful social interaction soon after the arrival of residents into the home, at regular points in the year such as Christmas or the summer, as well as in ongoing everyday practice. Additionally, while my findings suggest that material culture in residential homes can help to foster close relationships between residents and staff, they also demonstrate that failure by staff members to treat residents’ possessions with respect can undermine relationships, and this could be made explicit in care home policies.

I have argued that through in-depth ethnographic research into how residents of older people's homes interact with material culture, we can learn new insights into the relationships that matter to older people, and how they are sustained and constructed. This was a small study of one residential home for older people, where the participants were in relatively good physical and cognitive health. Although I have suggested activities and practices that residential settings could adopt in order to encourage the maintenance and construction of social relationships, more research is needed to explore which strategies might be most effective with residents of different cognitive and physical abilities. The findings presented in this paper provide examples of male and female residents using objects to stay socially connected, but this was only a small sample size and gendered differences were not a central focus of the research. Further research focusing on how gender might influence materially mediated social interactions would be potentially useful to practitioners and contribute to research on the effectiveness of gendered social interventions in later life (Milligan et al., Reference Milligan, Neary, Payne, Hanratty, Irwin and Dowrick2016).

With loneliness recognised as a threat to people's physical and mental health (Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, 2018), identifying ways to increase meaningful social interaction is crucial. The research presented here suggests that by interacting with material possessions, residents of an older people's home can help to maintain relationships with family members outside the home, as well as form new relationships with fellow residents and members of staff.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to the study participants and two anonymous reviewers.

Ethical standards

The project received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Sheffield.