Introduction

The views of ageing and physical activity in Western culture have evolved continuously, generating various types of perspectives. From the traditional medicalised view of ageing, according to the disengagement theory developed by Cumming and Henry (Reference Cumming and Henry1961), ageing can be viewed as an inevitable declining process resulting in fewer social interactions between the ageing individual and others in the social system. The traditional field of gerontology has provided invaluable information on the ageing process and on people who were ill or suffering from major and chronic diseases such as cancers, dementia or diabetes, highlighting a negative view of ageing based on a model of biological decline.

On the other hand, from a positive ageing view, based on the activity theory developed by Havighurst (Reference Havighurst1961), it is suggested that successful ageing is possible through being active and sustaining social interactions. A positive ageing view emerged in the 1970s, producing academic publications, theories, images or attitudes about promoting later life as a period of enjoyment, growth, creativity, independence and development, rather than solely focused on disengagement, loneliness and decline (Gergen and Gergen, Reference Gergen and Gergen2001; Tornstam, Reference Tornstam2005). Recently, several studies found that more positive views on ageing relate to better individual health outcomes including physical functioning/physical health (Sargent-Cox et al., Reference Sargent-Cox, Anstey and Luszcz2012; Levy et al., Reference Levy, Pilver, Chung and Slade2014; Hicks and Siedlecki, Reference Hicks and Siedlecki2017) or subjective health (e.g. Ware et al., Reference Ware, Kosinski and Keller1996; Kim, Reference Kim2009). This line of positive ageing literature has stimulated the health and fitness promotion movement by government and business corporations (McPherson, Reference McPherson1999). These days, a prevalent idea is that older people should take preventive measures to stay physically active, healthy and live independently for as long as possible. This idea reflects a cultural emphasis on physical activity, leisure and sport as strategies for maintaining the physical, social and psychological health of older people and resisting the ageing body (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2002; Dionigi, Reference Dionigi2006a).

Even though this concept of successful ageing generated a transition for the field of gerontology, it also should be noted that the concept is not free from criticism (Pruchno, Reference Pruchno2015). Several scholars highlight the over-emphasis on individual behaviour, overlooking the importance of factors relevant to social exclusion such as gender, race and age (Katz and Calasanti, Reference Katz and Calasanti2015; Rubinstein and de Medeiros, Reference Rubinstein and de Medeiros2015), failing to acknowledge historical and cultural context (Stowe and Cooney, Reference Stowe and Cooney2015) or environments (Golant, Reference Golant2015), and failing to provide policy agenda strategies for the social and cultural change (Rubinstein and de Medeiros, Reference Rubinstein and de Medeiros2015). While these various views of ageing have been developed, the empirical studies on the psychological and social benefits of sport participation for older adults have been fragmented (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Stratas and Karlis2017). In this study, the term psychological is used as a synonym for mental and psycho-social, i.e. any situation in which both psychological and social factors are presumed to have an influence (Reber et al., Reference Reber, Allen and Reber2009).

As strategies to promote health through physical activity and sports for the public, many sport organisations (e.g. government, Young Men's Christian Association) have focused on the development of elite athletes and the promotion of sport participation for the public (Chalip, Reference Chalip2011). Reflecting this trend, several studies investigated the status and effects of sport participation for children/adolescents (e.g. Craig and Bauman, Reference Craig and Bauman2014; Bean and Forneris, Reference Bean and Forneris2017; Gardner et al., Reference Gardner, Magee and Vella2017; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Pope and Goao2018) and adults (e.g. Bice et al., Reference Bice, Ball and Brown2014; Green, Reference Green2014). However, relatively little research focused on older adults (i.e. we define the age ranges of older adults as 50 years and older based on previous studies; King et al., Reference King, Rejeski and Buchner1998; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Shi, Yu and Qiu2016), despite the fact that there have been unique motives, barriers and outcomes of sport participation for older adults. For instance, a senior athlete is inclined to experience different psycho-social challenges than younger athletes in that the senior athletes tend to have more professional, familial and social obligations which can be critical distractions from training (Menard and Stanish, Reference Menard and Stanish1989). Senior athletes also tend to be more stressed about their declining physical functioning. The meanings and experiences of competition at the sporting events for older adults are different from the ones for younger people in that competing at the sporting events enables the senior athletes to resist the stereotypes of ‘being old’ and take pride in playing a competitive sport in later life (Grant, Reference Grant2001; Dionigi and O'Flynn, Reference Dionigi and O'Flynn2007; Liechty et al., Reference Liechty, West, Naar and Son2017). While such views by senior athletes may be worthwhile from a health promotion perspective, several scholars also recognised that it simultaneously produces a particular moral subject position of active participation in sport as good and those who do not participate in active physical activity can be stigmatised, victimised, medicalised and ignored in public health policy (Fullagar, Reference Fullagar2001; Dionigi and O'Flynn, Reference Dionigi and O'Flynn2007).

Sport is one dominant form of physical activity that can be crucial for the public health agenda (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Warner and Das2015). Physical activity is defined as ‘any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure above resting level’ (Caspersen et al., Reference Caspersen, Powell and Christenson1985: 126). Sport is defined as ‘all forms of physical activity which, through casual or organized participation, aim at expressing or improving physical fitness and mental wellbeing, forming social relationships or obtaining results in competition at all levels’ (Council of Europe, 2001) or ‘a human activity involving physical exertion and skill as the primary focus of the activity, with elements of competition where rules and patterns of behavior governing the activity exist formally through organization’ (Australian Sports Commission, 2017). As the definition of sport provided by the Council of Europe (2001) presents, sport can not only improve older adults’ physical health, but can also enhance psychological and social health which can be associated with positive mental health. Conversely, several scholars have criticised the promotion of active sport participation as a public agenda, highlighting the danger of overlooking the opposing viewpoint of active ageing. Using active sport participation by sport organisations and governments across the world without clear-cut empirical evidence can disregard people who are not or cannot actively participate in sport unattended and are left out from the public health policy (Gilleard and Higgs, Reference Gilleard and Higgs2002; Dionigi, Reference Dionigi2006a; Gard and Dionigi, Reference Gard and Dionigi2016). Even though it has been argued that team sport participation tends to be linked with positive health outcomes compared to individual physical activity or exercise because of the social nature of the participation (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Warner and Das2015), few studies have been conducted (Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Baker and Horton2011; Gayman et al., Reference Gayman, Fraser-Thomas, Dionigi, Horton and Baker2017) and the findings of the psychological and social benefits of sport participation for older adults are still fragmented (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Stratas and Karlis2017).

It has been reported that many older adults have participated in different types of sports. For instance, the United States Tennis Association and the United States of America Pickleball Association run the age-stratified leagues at the local, state and national levels for players who are older than 50 and 65. In addition, the National Senior Games Association hosts the biennial National Senior Games that allows people who are older than 50 to compete in archery, badminton, basketball, bowling, cycling, golf, horseshoes, pickleball, power walk, race walk, racquetball, road race, shuffleboard, softball, swimming, table tennis, tennis, track and field, triathlon and volleyball. As Kirby and Kluge (Reference Kirby and Kluge2013: 292) stated, ‘the creation and growth of organizations that sponsor competitive events for older adults has enabled older adults to challenge social stereotypes and remain in the world of competitive sports or joining a world once thought exclusive to the elite, young, and fit’. Regardless of the label, continuously increased participation has been recognised by entries in regional, national and international events (Cardenas et al., Reference Cardenas, Henderson and Wilson2009; Pfister, Reference Pfister2012; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Stratas and Karlis2017). Despite substantial public investment in sport development for older adults, there has been no clear understanding of the best way to achieve maximum psychological and social health (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Stratas and Karlis2017).

To promote sport participation among older adults, an extensive range of studies has been conducted to examine the motivations and barriers of sport participation among older adults (e.g. Rotella and Bunker, Reference Rotella and Bunker1978; Newton and Fry, Reference Newton and Fry1998; Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Ostrou and Beckstead2005; Reed and Cox, Reference Reed and Cox2007; Yamada and Heo, Reference Yamada and Heo2016). Yet, not many studies have examined the benefits of sport participation among older adults. Especially, the previous literature on older adults’ sport participation has focused prevalently on either physical or physiological outcomes related to sport involvement (e.g. Tanaka and Seals, Reference Tanaka and Seals2003; Iermakov et al., Reference Iermakov, Podrigalo, Romanenko, Tropin and Boychenko2016). Several studies have investigated the psychological outcomes associated with sport involvement, but only focused on non-competitive and relatively low levels of physical activity such as Tai Chi (e.g. Jin, Reference Jin1989; Bonura and Tenenbaum, Reference Bonura and Tenenbaum2014).

In sum, to identify the gap and reflect the current status of academic literature for sport participation among older adults, the aim of the present systematic review is to explore the positive and negative psychological and social outcomes of older adults’ sport participation.

Methods

Search strategy

A total of seven major bibliographical databases (i.e. SPORTDiscuss, Cochrane Library, PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES and CINAHL) were searched to explore psychological and social outcomes of sport participation among older adults. Further, more articles were identified through back referencing. Keywords were composed of four groups:

• Group 1: sport, physical activity, exercise, leisure.

• Group 2: health.

• Group 3: benefit, impact, improvement, effect, outcome, value.

• Group 4: mental health, psychology, depression, stress, anxiety, happiness, mood, quality of life, subjective wellbeing, life satisfaction, social health, sociology, social benefit, social functioning, social relations, social capital, social connect, social network.

Based on these groups, searches were conducted by input Group 1 AND Group 2 AND Group 3 AND Group 4 to each of the seven electronic databases.

Data selection strategy

The publications were included in the review if they satisfied the following criteria:

(1) Studies or reports published in the English language until December 2017 including articles in press.

(2) Studies published in peer review journals or peer-reviewed reports published in government or other organisations based on primary data.

(3) Studies or reports that presented data to address mental, psychological and/or social health benefits from sport participation. Here, sport is defined as ‘a human activity involving physical exertion and skill as the primary focus of the activity, with elements of competition where rules and patterns of behaviour governing the activity exist formally through organization’ (Australian Sports Commission, 2017).

(4) Studies or reports that investigated the effect of sport participation for older adults (older than 50 years) (e.g. King et al., Reference King, Rejeski and Buchner1998; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Shi, Yu and Qiu2016).

The publications were excluded from the review if they were:

(1) Studies or reports that focused on physical activity, exercise or physical education, and not sport. In this study, physical activity is defined as ‘bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure’ (Caspersen et al., Reference Caspersen, Powell and Christenson1985: 126). Exercise is defined as ‘physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and purposive in the sense that improvement or maintenance of one or more components of physical fitness is an objective’ (Casperson et al., Reference Caspersen, Powell and Christenson1985: 128). Physical education is defined as ‘a sequential, developmentally appropriate educational experience that engages students in learning and understanding movement activities that are personally and socially meaningful, with the goal of promoting healthy living (Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, 2009: 8).

(2) Studies or reports that focused on ‘exergaming’. Exergaming is defined as ‘technology-driven physical activities, such as video game play, that requires participants to be physically active or exercise in order to play the game’ (American College of Sports Medicine, 2013).

(3) Research or reports that tackled ‘adapted’ participation (e.g. physical activity, exercise or sport participation for individuals with a physical and/or intellectual disability).

(4) Research or reports that investigated the effect of sport participation for children, adolescents and adults (younger than 50 years).

(5) Research or reports that included sub-populations at specific risk.

(6) Book chapters, abstracts, dissertations and conference proceedings.

Data extraction process

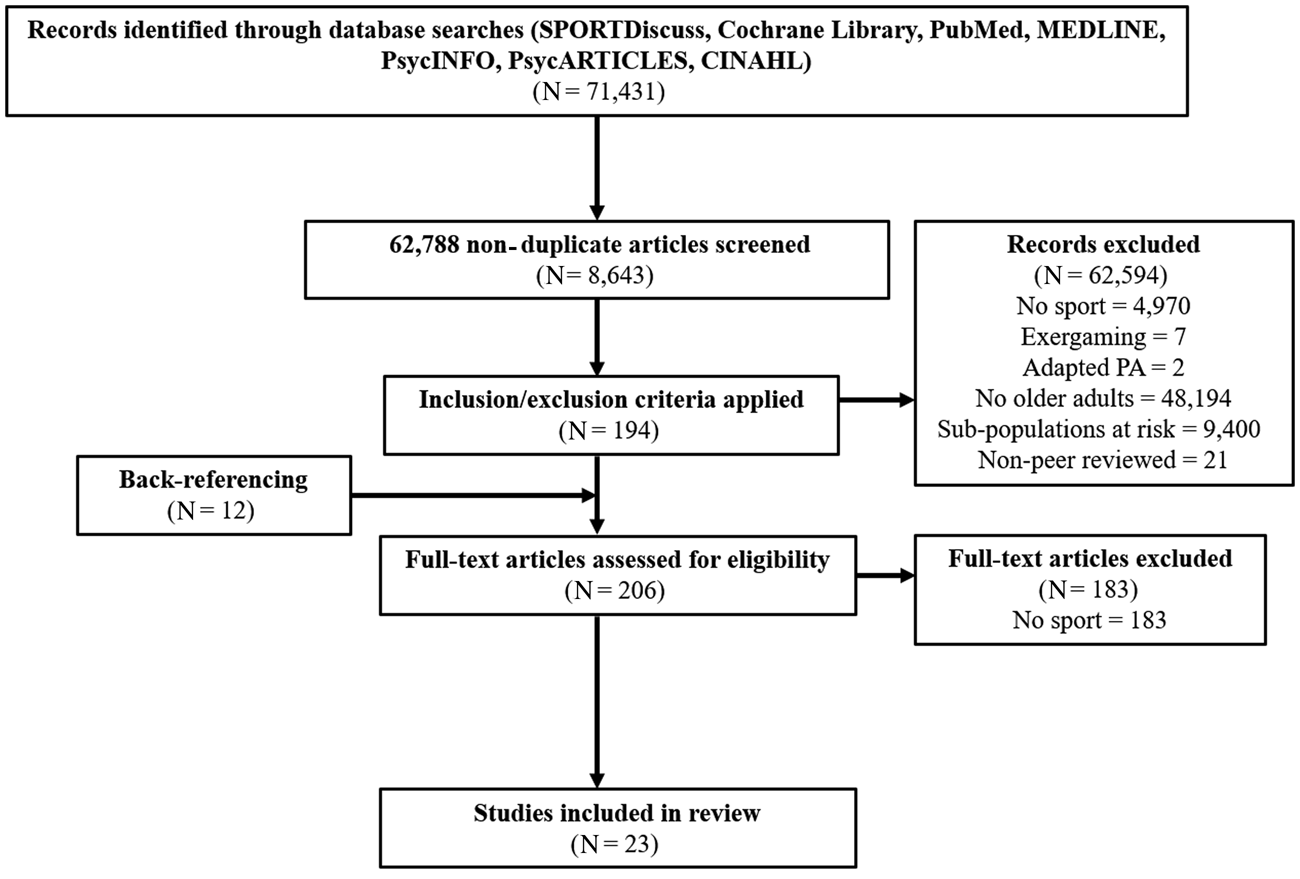

Two steps were involved in the identification and inclusion of articles. First, three researchers independently screened each abstract to decide initially on its suitability for inclusion. Next, three reviewers read each article independently. A fourth reviewer evaluated the study if disagreement occurred between the reviewers so that consensus could be reached through discussion. After this process, a total of 23 articles were included in the current review. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow chart for stages of article selection and extraction (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). Initially, a total of 71,431 articles were identified through database searches, and 8,643 duplicated articles were excluded. After reviewing the titles and abstracts of 62,788 articles, a total of 62,594 articles were excluded based on the exclusion criteria resulting in a total of 194 full-text articles for further assessment of eligibility. With these 194 articles, using a back-referencing process, we identified 12 more relevant studies. During the full-text review process, we included only the studies that examined the participants of sport participation excluding studies which examined the combination of sport participation and other leisure activities (e.g. board game, volunteering) or informal physical activities (e.g. walking with dogs, running). After the final full-text review, a total of 23 articles were included in the current review.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart for stages of article selection and extraction.

Data analysis and quality assessment

Extracted data are presented in a table including authors, research design, sample and setting, sport variable, theory and major findings (see Table 1). For assessing the quality of selected articles, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) developed by Pluye et al. (Reference Pluye, Robert, Cargo, Barlett, O'Cathain, Griffiths, Boardman, Gagnon and Rousseau2011) was used because the reliability and efficiency has been confirmed, showing that agreement between reviewers was moderate to excellent for the MMAT criteria (Pace et al., Reference Pace, Pluye, Bartlett, Macaulay, Salsberg, Jagosh and Seller2012; Suoto et al., Reference Suoto, Khanassov, Hong, Bush, Vedel and Pluye2015). The MMAT is composed of five types of components (i.e. qualitative; quantitative, randomised, controlled trials; quantitative non-randomised; quantitative descriptive; mixed methods) and each has its own set of methodological quality criteria based on the existing published criteria. The answer categories are ‘yes,’ ‘no’ and ‘can't tell’ followed by comments (Pluye et al., Reference Pluye, Robert, Cargo, Barlett, O'Cathain, Griffiths, Boardman, Gagnon and Rousseau2011). Two reviewers scored the quality of included studies independently. The intercoder reliability was 96 per cent. The disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion. MMAT ratings are included in the first column of Table 1. Articles included in this stage of the research had acceptable quality (Anderson and Keating, Reference Anderson and Keating2018).

Table 1. Summary of studies included in the review

Notes: 1. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool assessment: scores varying from 25 per cent (*; one criterion met) to 100 per cent (****; all four criteria met). USA: United States of America. N/A: not applicable.

Results

Included studies

Of the 23 publications, no studies were excluded based on the results of quality assessment (Anderson and Keating, Reference Anderson and Keating2018). Overall, three studies met all of the MMAT criteria (Heuser, Reference Heuser2005; Dionigi, Reference Dionigi2006a; Kirby and Kluge, Reference Kirby and Kluge2013), 12 studies met 75 per cent (Grant, Reference Grant2001; Dionigi, Reference Dionigi2005; Dionigi and O'Flynn, Reference Dionigi and O'Flynn2007; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Baker and Horton2011, Reference Dionigi, Horton and Baker2013; Müller et al., Reference Müller, Gimpl, Poetzelsberger, Finkenzeller and Scheiber2011; Eman, Reference Eman2012; Kelley et al., Reference Kelley, Little, Lee, Birendra and Henderson2014; Bardhoshi et al., Reference Bardhoshi, Jordre, Schweinle and Shervey2016; Liechty et al., Reference Liechty, West, Naar and Son2017; Naar et al., Reference Naar, Wong, West, Son and Liechty2017), seven studies met 50 per cent (Dionigi, Reference Dionigi2006b; Heo and Lee, Reference Heo and Lee2010; Heo et al., Reference Heo, Lee, Kim and Stebbins2012, Reference Heo, Stebbins, Kim and Lee2013a, Reference Heo, Culp, Yamada and Won2013b, Reference Heo, Ryu, Yang, Kim and Rhee2018; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Yamada, Harvey and Han2014; Östlund-Lagerström et al., Reference Östlund-Lagerström, Blomberg, Algilani, Schoultz, Kihlgren, Brummer and Shoultz2015) and one study met 25 per cent of the criteria (Finkenzeller et al., Reference Finkenzeller, Muller, Wurth and Amesberger2011).

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 presents the summary of included studies for the review. The qualitative studies had varied sample sizes ranging from six to 138 participants. The quantitative studies had relatively larger samples sizes ranging from 47 to 459. Two mixed studies had 374 and 383 participants, respectively. When it comes to the age of participants, three studies reported the mean age of the samples as 67.5, 67.3 and 67.29 years old. One study examined the participants who were in their seventies (70–79 years old), seven studies studied samples who were older than 60 years and 12 studies studied samples who were older than 50 years.

In terms of the gender of the samples, two studies solely focused on the experiences of female sport participants whereas 21 studies included both female and male samples. There was no study focused solely on male participants. Eight studies reported the race information of each participant. Of these eight studies, the majority of the samples for seven studies were White participants ranging from 88.1 to 94.1 per cent. One study solely focused on South Korean participants.

Six studies reported the education information of their samples. Four studies reported that more than 50 per cent of their samples graduated from college (ranging from 53 to 100 per cent) and three studies reported that some of their samples obtained more than college degrees (ranging from 23.5 to 43 per cent). Ten studies reported the retirement status of the samples. More than 50 per cent of retired participants were included in their samples in all ten studies (ranging from 50 to 100 per cent).

When it comes to the conceptualisation of sport participation, one study conceptualised the sport participation of samples as a ‘career’ whereas four studies conceptualised sport participation of samples as serious leisure activities.

Psychological and social outcomes

Subjective wellbeing

Of the 23 studies, four publications examined life satisfaction as an outcome of alpine skiing (Finkenzeller et al., Reference Finkenzeller, Muller, Wurth and Amesberger2011), competing at the Senior Games (Heo and Lee, Reference Heo and Lee2010; Heo et al., Reference Heo, Stebbins, Kim and Lee2013a) and playing pickleball (Heo et al., Reference Heo, Ryu, Yang, Kim and Rhee2018) among older adults. Subjective wellbeing has been identified as a key indicator of health and quality of life in various academic disciplines. While subjective wellbeing is usually employed to assess hedonic pleasure in human experience (Diener, Reference Diener2000), life satisfaction has been regarded as a key indicator for subjective wellbeing (Steverink and Lindenberg, Reference Steverink and Lindenberg2006; Diener et al., Reference Diener, Inglehart and Tay2013). Finkenzeller et al. (Reference Finkenzeller, Muller, Wurth and Amesberger2011) found that skiing intervention significantly increased participants’ levels of life satisfaction, especially two dimensions including friends and relatives, and the physical self-concepts. While the studies of Heo and Lee (Reference Heo and Lee2010) and Heo et al. (Reference Heo, Stebbins, Kim and Lee2013a, Reference Heo, Ryu, Yang, Kim and Rhee2018) consistently showed that participating in sports (i.e. Senior Games, pickleball) predicted a higher level of life satisfaction, Heo et al. (Reference Heo, Stebbins, Kim and Lee2013a) specifically confirmed a positive relationship between the level of sport involvement and life satisfaction.

Psychological distress and mood state

A total of four publications examined the relationship between sport participation and mental health including mood state and psychological distress such as depression, anxiety and stress. Inconsistent findings were identified in the relationship. Östlund-Lagerström et al. (Reference Östlund-Lagerström, Blomberg, Algilani, Schoultz, Kihlgren, Brummer and Shoultz2015) found that all physiological health factors of senior orienteering athletes were significantly better than the free-living older adults except for the levels of anxiety and depression. Similarly, Finkenzeller et al. (Reference Finkenzeller, Muller, Wurth and Amesberger2011) found no significant change among the subjects of skiing intervention groups. Conversely, Müller et al. (Reference Müller, Gimpl, Poetzelsberger, Finkenzeller and Scheiber2011) found that skiing was effective as a positive mood modifier, showing a very positive mood and very low negative mood on ski days among the subjects of the intervention group. Consistent with this finding, Bardhoshi et al. (Reference Bardhoshi, Jordre, Schweinle and Shervey2016) also confirmed significantly lower DASS-21 (Depression Anxiety Stress Scales) scores for Senior Games athletes compared with non-athletes among older adults.

Personal psychological enhancement

Findings regarding personal psychological enhancement and sport participation were mixed in this review. Finkenzeller et al. (Reference Finkenzeller, Muller, Wurth and Amesberger2011) demonstrated that the skiing intervention did not significantly affect the level of self-efficacy among the samples in the intervention group. On the contrary, Dionigi (Reference Dionigi2006a) and Dionigi et al. (Reference Dionigi, Baker and Horton2011) found that the Masters Games athletes had a high level of self-efficacy and expressed feelings of personal empowerment. Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Yamada, Harvey and Han2014) reported that Korean older adults enjoyed enhanced self-esteem and confidence through sport participation. Similarly, Naar et al. (Reference Naar, Wong, West, Son and Liechty2017) reported that softball participants enhanced self-confidence and self-worth through softball participation.

Hedonistic value and social outcomes

Nine publications found the hedonistic value and social benefits of sport participation among older adults. Kirby and Kluge (Reference Kirby and Kluge2013) found that volleyball participants had fun and enjoyed challenges from playing volleyball. Dionigi (Reference Dionigi2006a, Reference Dionigi2006b) and Dionigi et al. (Reference Dionigi, Baker and Horton2011) reported that sport participation enabled participants to socialise with other participants, generating friendships with each other. Similarly, according to Heo et al. (Reference Heo, Culp, Yamada and Won2013b), the participants of the Senior Games addressed social networking, pure fun, social belonging and interactions with other competitors as social benefits. They also found that the research participants identified a unique ethos (i.e. developing a special social world) through sport participation. Regarding the unique ethos among Senior Games participants, Heo et al. (Reference Heo, Lee, Kim and Stebbins2012) confirmed that unique ethos is one significant personal outcome, and perseverance and career contingency were significant predictors of unique ethos. Naar et al. (Reference Naar, Wong, West, Son and Liechty2017) found softball participants used the recruitment process as a form of socialisation into softball. Similarly, in the study by Kelley et al. (Reference Kelley, Little, Lee, Birendra and Henderson2014), the Senior Games participants identified being part of a collective experience as a meaningful experience for them. Heuser (Reference Heuser2005) highlighted that involvement in lawn bowling was significant for the samples in that they build and enhance social relationships through the sport participation regardless of the level of involvement. Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Yamada, Harvey and Han2014) identified that participating in sport clubs generated social support among participants in South Korea. Related to the social benefits, it should be noted that all the studies except for one study (Heo et al., Reference Heo, Lee, Kim and Stebbins2012) were conducted using qualitative methods.

Competition

Dionigi (Reference Dionigi2006a) and Dionigi et al. (Reference Dionigi, Baker and Horton2011) argued that the participants in Masters Games valued competitiveness in physical sports by comparing their performance levels to others, enhancing their bodies to attain a personal best, and enjoying the recognition that came from achieving and winning in competitive sports. In particular, Dionigi et al. (Reference Dionigi, Baker and Horton2011) highlighted that competitions motivated the participants to work harder for better performance. In the same vein, Kelley et al. (Reference Kelley, Little, Lee, Birendra and Henderson2014) found that participants of the Senior Games tended to distinguish themselves through competition by comparing themselves to others, and persevering through and overcoming challenges.

Resisting the negative view of ageing

Of 23 studies, eight studies (Grant, Reference Grant2001; Dionigi, Reference Dionigi2005, Reference Dionigi2006a, Reference Dionigi2006b; Dionigi and O'Flynn, Reference Dionigi and O'Flynn2007; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Baker2013; Eman, Reference Eman2012; Kelley et al., Reference Kelley, Little, Lee, Birendra and Henderson2014; Liechty et al., Reference Liechty, West, Naar and Son2017) described that senior sport participants used active sport involvement as a means to challenge negative traditional and stereotypical views and images of ageing (e.g. ‘playing sport at your age’). These studies explored how older adults continuously manage their ageing process with resistance, avoidance, adaptation and acceptance through sport participation. While resisting the view of ageing by senior athletes is critical for the public health promotion agenda, several scholars also highlighted the danger of this view. That is, such a view also generates a particular social norm of active participation in sport as good and the right thing to do and those who do not participate in active physical activity can be stigmatised and excluded from public health policy (Fullagar, Reference Fullagar2001; Dionigi and O'Flynn, Reference Dionigi and O'Flynn2007).

Discussion

This review presents a handful of studies that explored the psychological and social outcomes of sport participation among older adults. Consistent with findings of previous studies, the included studies found that sport participation could enhance older adults’ life satisfaction, social life (e.g. comraderies, unique social networking, social belonging, a sense of community) and personal psychological status (e.g. personal empowerment, self-confidence, self-worth, self-esteem, self-efficacy, pride) (Eime et al., Reference Eime, Young, Harvey, Charity and Payne2013a, Reference Eime, Young, Harvey, Charity and Payne2013b).

When it comes to psychological distress, the included publications present contradicting results demonstrating no significant effects (i.e. Finkenzeller et al., Reference Finkenzeller, Muller, Wurth and Amesberger2011; Östlund-Lagerström et al., Reference Östlund-Lagerström, Blomberg, Algilani, Schoultz, Kihlgren, Brummer and Shoultz2015) or significantly positive effects (i.e. Müller et al., Reference Müller, Gimpl, Poetzelsberger, Finkenzeller and Scheiber2011; Bardhoshi et al., Reference Bardhoshi, Jordre, Schweinle and Shervey2016) among senior sport participants. Two studies of Dionigi (Reference Dionigi2006a) and Kelley et al. (Reference Kelley, Little, Lee, Birendra and Henderson2014) highlighted that the Masters Games and Senior Games participants valued competition itself by comparing their performance levels to others, pushing their bodies to attain a personal best, and enjoying the recognition and achievements. One unique role of sport participation among older adults was that senior sport participants tried to resist the negative stereotypical views of ageing through sport involvement. Several studies (Grant, Reference Grant2001; Dionigi, Reference Dionigi2005, Reference Dionigi2006a, Reference Dionigi2006b; Dionigi and O'Flynn, Reference Dionigi and O'Flynn2007; Eman, Reference Eman2012; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Horton and Baker2013; Kelley et al., Reference Kelley, Little, Lee, Birendra and Henderson2014; Liechty et al., Reference Liechty, West, Naar and Son2017) found that continuing sport participation was meaningful for older adults to avoid and resist the view of ‘being old’. These older individuals expressed that continued involvement in competitive sport participation can delay and control the ageing process. From a successful ageing perspective, this view is noteworthy in that it stimulates the older adults to be more physically active to stay healthier. Nevertheless, at the same time, several researchers highlighted the negative side of this type of view, implying that such a view can stigmatise and neglect individuals who are not physically active in public health policy (Fullagar, Reference Fullagar2001; Dionigi and O'Flynn, Reference Dionigi and O'Flynn2007).

Given that one of the most commonly identified outcomes were fewer depressive symptoms among children/adolescents, and reduced stress and distress among adults who participated in sport programmes (Eime et al., Reference Eime, Young, Harvey, Charity and Payne2013a, Reference Eime, Young, Harvey, Charity and Payne2013b), it was interesting that inconsistent results were found in the included articles among older adults. In fact, Hoar et al. (Reference Hoar, Evans and Link2012) found that roughly 70 per cent of the sample (older master athletes who participate in a Senior Winter Games) reported pre-competitive stress. Five different types of stressor included performance, logistics, novelty, preparation and health, whereas the most common coping strategies were problem-solving, and seeking support and accommodation. It is well-known that stress affects one's mental health, such as depression and hopelessness (e.g. Ciarrochi et al., Reference Ciarrochi, Deane and Anderson2002; Shavitt et al., Reference Shavitt, Cho, Johnson, Jiang, Holbrook and Stavrakantonaki2016). Hence, it is noteworthy to investigate the potential significant influence stress has on mental health among senior athletes in the future, considering various factors that can influence stress responses such as personality (Dawson and Thompson, Reference Dawson and Thompson2017).

Even though three studies (Heo and Lee, Reference Heo and Lee2010; Heo et al., Reference Heo, Stebbins, Kim and Lee2013a, Reference Heo, Ryu, Yang, Kim and Rhee2018) found that sport involvement tended to predict a higher level of life satisfaction, the causal relationship has not been fully examined. Aside from the level of sport involvement, a level of life satisfaction is also affected significantly by socio-demographic factors and socio-economic factors such as race (Broman, Reference Broman1997), financial status (Usui et al., Reference Usui, Keil and Durig1985), sense of community (Prezza et al., Reference Prezza, Amici, Roberti and Tedeschi2001) or religion-related social networks (Krause, Reference Krause2008; Lim and Putnam, Reference Lim and Putnam2010). Despite the fact that Heo et al. (Reference Heo, Ryu, Yang, Kim and Rhee2018) found the positive relationship between a level of sport involvement and life satisfaction after controlling some socio-demographic factors such as age, gender, educational level, marital status and occupational status, all three studies were cross-sectional and non-experimental studies, indicating the lack of internal validity. More rigorous research designs such as longitudinal and experimental design need to be employed in the future in order to confirm the influence of sport involvement on life satisfaction.

The findings show that the psychological and social effects of sport involvement on older adults are still unexplored and limited. Eime et al. (Reference Eime, Young, Harvey, Charity and Payne2013a) identified 40 different psychological and social outcomes of sport participation among children and adolescents and 13 different psychological and social outcomes of sport participation among adults (Eime et al., Reference Eime, Young, Harvey, Charity and Payne2013b). A majority of these outcome measures also need to be examined in the context of older adults’ sport participation.

Even though the various instruments have been developed to assess the sport participation of children and adolescents (e.g. Sports Participation and Attitudes Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents by Donaldson and Ronan, Reference Donaldson and Ronan2006), there has been no attempt to develop new instruments to evaluate the level of sport participation and related behavioural patterns for older adults or to modify the previous ones of younger generations to older generations. Most of the included studies in this review studied lifelong athletes. In order to assess the psychological and social outcomes depending on the different level of involvement, the use of proper instruments for sport participation for older adults are required.

Related to the different levels of involvement, future studies need to develop and test the construct of sport involvement among older adults. In fact, Beaton et al. (Reference Beaton, Funk, Ridinger and Jordan2011: 128) conceptualised and operationalised the construct of sport involvement which is defined as ‘is present when individuals evaluate their participation in a sport activity as a central component of their life that provides both hedonic and symbolic value’. Whereas they attempted to operationalise the level of sport involvement with the Psychological Continuum Model (Funk and James, Reference Funk and James2001) and three involvement facets (i.e. hedonic value, centrality, symbolic value), they did not address the unique values of sport participation among older adults such as resistance to the negative view of ‘ageing’ and value of being ‘competitive’ in sport activities.

In a similar context, several studies (e.g. Heo and Lee, Reference Heo and Lee2010; Heo et al., Reference Heo, Lee, Kim and Stebbins2012, Reference Heo, Stebbins, Kim and Lee2013a, Reference Heo, Culp, Yamada and Won2013b, Reference Heo, Ryu, Yang, Kim and Rhee2018) conceptualised and operationalised the construct of serious involvement and used senior athletes and pickleball players as one part of serious leisure participants. Serious leisure is distinguished from casual leisure based on six characteristics: (a) need to persevere at the activity, (b) development of a leisure career, (c) need to put in effort to gain skill and knowledge, (d) gaining social and personal benefits, (e) unique ethos and social world, and (f) an attractive personal and social identity (Stebbins, Reference Stebbins2007). Even though this construct and relevant instruments may be beneficial for exploring the devoted sport participants, it is hard to explore the characteristics of sport participants at the other end (i.e. casual leisure). According to Baker et al. (Reference Baker, Horton and Weir2010), there are individuals who are motivated to participate in sports in their later years, arguing that more studies need to be conducted about the antecedents and consequences of sport participation for newcomers to sport among older adults. In fact, few studies addressed that competitive sport participation for late starters is inclined to build a new or alternative personal identity as a winner and a highly physically active person (Grant, Reference Grant2001; Dionigi et al., Reference Dionigi, Baker and Horton2011). Nevertheless, further investigations are required to develop conceptual and theoretical frameworks and relevant instruments to explore what influences the emergence of this new identity and how it affects the late starters’ lives more in depth, in order to explore the behaviour of newcomers and casual older sport participants.

The results of this study recognise the lack of experimental and longitudinal research designs in the line of research of sport participation among older adults. Only two studies (Finkenzeller et al., Reference Finkenzeller, Muller, Wurth and Amesberger2011; Müller et al., Reference Müller, Gimpl, Poetzelsberger, Finkenzeller and Scheiber2011) used sport participation as an intervention according to our review. Because of the lack of controlled settings, it is hard to identify a causal association between psychological and social outcomes and sport participation among older adults. Smith and Storandt (Reference Smith and Storandt1997) explored a continuum of sport participation among older adults by studying three different types of older adult sport participants. They classified non-exercisers as people who had not participated in any aerobic exercise, non-competitors as people who exercised routinely but did not compete, and competitors as people who exercised regularly and had participated in an athletic competition within the past five years (e.g. tennis tournaments, running races, softball tournaments). The results of this study demonstrated that competitors reported exercise as significantly more important and had more reasons for exercising than did non-exercisers and non-competitors. Non-exercisers considered reducing stress and improving mood to be less critical reasons for exercising than did competitors and non-competitors (Smith and Storandt, Reference Smith and Storandt1997). Vallerand and Young (Reference Vallerand and Young2014) explored how motives predict levels of physical activity commitment and lapses differently between sport participants and exercisers. The authors found that sport participants reported competition and social-affiliation motives higher than exercisers while both sportspersons and exercisers valued enjoyment, stress relief and social-affiliation motives for their commitment. In the future, it is critical to investigate the differences among sport participants, sports plus exercisers, and exercisers in terms of psychological and social benefits among older adults through intervention-based studies and longitudinal studies. This may reveal the distinctive role of sport participation from exercise or physical activity participation by older adults. This information is helpful for sport event managers to organise, promote and manage sport events for older adults maximising the positive benefits of active sport participation.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The sample of studies tended to be homogeneous groups of highly educated and Caucasian older adults (Dionigi and O'Flynn, Reference Dionigi and O'Flynn2007; Heo and Lee, Reference Heo and Lee2010; Heo et al., Reference Heo, Lee, Kim and Stebbins2012, Reference Heo, Stebbins, Kim and Lee2013a, Reference Heo, Culp, Yamada and Won2013b, Reference Heo, Ryu, Yang, Kim and Rhee2018; Bardhoshi et al., Reference Bardhoshi, Jordre, Schweinle and Shervey2016; Liechty et al., Reference Liechty, West, Naar and Son2017; Naar et al., Reference Naar, Wong, West, Son and Liechty2017). Several studies suggested that socio-demographic variables such as level of activity investment, gender, education level and retirement status may moderate the relationship between sport participation and certain benefits (e.g. Tedrick and MacNeil, Reference Tedrick and MacNeil1991; Weir et al., Reference Weir, Baker, Horton, Baker, Horton and Weir2010; Heo et al., Reference Heo, Ryu, Yang, Kim and Rhee2018). Future studies should consider investigating a more heterogeneous group of older sport participants to evaluate the impact of socio-demographic variables on the relationship between sport participation and psychological/social outcomes. This study did not include studies that were written in a language other than English, which may have excluded important findings associated with sport participation among older adults in different cultures.

Synthesising findings of poorly reported studies can cause a threat to the validity of outcomes and conclusions of systematic reviews (Reynders and Di Girolamo, Reference Reynders and Di Girolamo2017). To address this issue, recently, the Cochrane Collaboration recommends that systematic reviewers contact original authors of studies included in review studies so that the reviewers can obtain additional information on poorly presented items (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Lasserson, Chandler, Tovey and Churchill2016). This method was not utilised due to the relatively small number of eligible intervention studies for the review. Nevertheless, future systematic reviewers should consider this method to avoid a threat to validity of outcomes and conclusions of studies, especially when the focus of review is intervention-based studies.

Conclusion

Sport participation promotes beneficial health outcomes for children and adolescents, but little is known about the psychological and social outcomes of sport participation for older adults. Studies have found that sport participation of older adults could improve their life satisfaction, social life and personal psychological status. Findings of this review suggest that developing new instruments to evaluate the different level of sport participation and investigating moderating factors such as socio-demographic variables and motivation among older adults should be considered when developing intervention programmes. The findings offer insight to understand better the causal relationships between sport participation and psychological and social health outcomes among older adults.

Author ORCIDs

Amy Chan Hyung Kim, 0000-0002-0443-6851