Introduction

The vast majority of older adults prefer to stay in their own homes as they age (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2011). The aim of existing community services such as home care, assisted transportation and day centres is to support older adults’ independence and successful living in their own homes (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2011; Health Council of Canada, 2012). However, despite these services, about 19 per cent of older adults report lacking companionship, feeling left out or feeling isolated (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2011; Canada's National Seniors Council, 2014). Loneliness and unmet emotional needs are associated with poorer health, reduced functional abilities and increased mortality (Perissinotto et al., Reference Perissinotto, Stijacic Cenzer and Covinsky2012; Shankar et al., Reference Shankar, McMunn, Demakakos, Hamer and Steptoe2017; Talarska et al., Reference Talarska, Kropińska, Strugala, Szewczyczak, Tobis and Wieczorowska-Tobis2017). Thus, alternative strategies to meet older adults’ needs must be developed to address this issue and promote healthy ageing in place (Levesque et al., Reference Levesque, Pineault, Hamel, Roberge, Kapetanakis, Simard and Prud'homme2012; Canada's National Seniors Council, 2014; Community Development Halton, 2016).

Companion animals may be an avenue worth exploring as a growing body of research has shown that human–animal interactions may have a positive impact on the health of various populations (Carson, Reference Carson2006; Fine and Beck, Reference Fine, Beck and Fine2015). For example, animal-based therapies used with children with autism or painful diseases (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Stangler, Narveson and Pettingell2009; Hoagwood et al., Reference Hoagwood, Acri, Morrissey and Peth-Pierce2017), hospitalised psychiatric patients (Barak et al., Reference Barak, Savorai, Mavashev and Beni2001; Kovács et al., Reference Kovács, Kis, Rózsa and Rózsa2004; Barker and Wolen, Reference Barker and Wolen2008; Bernabei et al., Reference Bernabei, De Ronchi, La Ferla, Moretti, Tonelli, Ferrari, Forlani and Atti2013) and older adults with neurocognitive disorders (Tribet et al., Reference Tribet, Boucharlat and Myslinski2008; Bernabei et al., Reference Bernabei, De Ronchi, La Ferla, Moretti, Tonelli, Ferrari, Forlani and Atti2013; Tournier et al., Reference Tournier, Vives and Postal2017) have shown positive results in reducing disturbing behaviours, stress and pain. In older adults, animal-assisted therapies have proven to be beneficial in improving mood, caloric intake, daily functioning and social interactions with people in nursing homes, especially those with dementia (Banks and Banks, Reference Banks and Banks2002; Edwards and Beck, Reference Edwards and Beck2002).

Although animal-assisted therapies have been extensively studied, these are not the same as pet ownership, which implies a psychological bond, a mutual relationship and greater daily responsibility towards the animal (Walsh, Reference Walsh2009). Companion animals depend exclusively on their owner for basic needs such as feeding, hygiene and medical care (Rosenkoetter, Reference Rosenkoetter1991). However, as part of the normal ageing process, older adults experience a progressive decline in their physical capacities or changes in their economic status, which may put both older adults and their companion animals at greater risk when or if the pet's needs exceed the older owner's capabilities (National Research Council (US) Panel on a Research Agenda and New Data for an Aging World, 2001; Johnson and Bibbo, Reference Johnson, Bibbo and Fine2015). Despite these potential risks, pet ownership is common among older adults: one-third of older Canadians report living with a household pet, and 25 per cent of them are 75 years or older (Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2016). Moreover, about 62 per cent of older owners consider their pets to be family members and close companions (Walsh, Reference Walsh2009; Johnson and Bibbo, Reference Johnson, Bibbo and Fine2015). This raises important questions about potential safety issues surrounding pet ownership by older adults, and whether they are outweighed by the perceived benefits of owning a companion animal. This scoping review maps main findings and identifies key gaps with respect to the pros (benefits/positive outcomes) and cons (risks/negative outcomes) of pet ownership in community-dwelling older adults, relating to psycho-social, physical and functional outcomes.

Methods

A scoping review was performed according to the five stages described in the methodological framework developed by Arksey and O'Malley (Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005) and revisited by Levac et al. (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010). This method was deemed appropriate because scoping reviews provide an overview of the extent and range of existing research in a particular field in order to examine the breadth and depth of current knowledge on a subject hypothesised to have received little attention, to synthesise and disseminate research results, and to identify gaps in the research literature (Arksey and O'Malley, Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005). This method uses a systematic yet iterative approach and attempts to determine the feasibility of conducting a systematic review (Arksey and O'Malley, Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005; Levac et al., Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010).

Stage 1: Identifying the research question

The research question was

• What are the reported outcomes (pros and cons) in the literature of pet ownership for community-dwelling older adults?

The question was formulated using a broad approach to ensure sufficient breadth during the literature search (Arksey and O'Malley, Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005). For this study, the term pet included any type of animal species that a person could own and was responsible for, including dogs, cats, birds and fish.

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

This step involved searching the scientific and grey (theses, memoirs, book chapters, government publications) literature from January 2000 to July 2018 in ten computerised databases deemed relevant (Abstracts in Social Gerontology, Academic Search Complete, Ageline, CINAHL, MEDLINE, Psychology and Behavioral Science Collection, PsycInfo, Social Work Abstracts, SocIndex and SCOPUS). The search query was generated by the authors (NO, EL, VP) and consisted of natural and controlled keywords pertaining to pets and older adults (see Table 1). Although the timespan and languages were determined at the outset, the research strategy was iterative, meaning that as familiarity with the literature increased, some search terms were redefined (Arksey and O'Malley, Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005). Two experienced librarians (FL, KR) validated the keywords and helped tailor the terms to each database. FL also helped to identify databases relevant to the research question and the target population. An effort was made to reduce noise in order to retrieve the greatest number of relevant articles while maintaining a manageable number of sources. For example, terms including ‘pet’ and ‘cat’ that are not related to animals (PET scan, PET/CT and catheter) were excluded. Additional sources were retrieved by skimming the references in relevant articles. Results from the databases were exported to reference manager Endnote and duplicates were eliminated manually and with the software.

Table 1. Example of search strategy used (MEDLINE)

Note: Adj2, Adjacent operator retrieves records with search terms next to each other. In this case, Adj2 refers to terms next to each other, in any order, up to 1 word in between.

Stage 3: Study selection

The first author (NO) screened all the titles and abstracts of the sources found, and 35 per cent were co-validated by two authors (VP, EL). Sources were included in this review if they were in English, French or Serbo-Croatian (native language of the first author), and if (a) the population was over 60 years old, regardless of their health; (b) they involved pet owners/ownership; and (c) they mentioned the pros (benefits/positive outcomes) or cons (risks/ negative outcomes) for older adults. Sources were excluded if they referred to (a) nursing homes or long-term care facilities; (b) pet robots or robot therapies; (c) animals needing specialised facilities (e.g. horses); or (d) animal-assisted therapies. A decision was made to exclude animals that could be considered pets but required specialised care (e.g. horses, farm animals) in order to encompass the most widespread and common cases of pet ownership. The same eligibility criteria were used for the grey literature search. No restrictions were applied to the type of reference included, which is in line with the aim of scoping reviews. After completing the selection by title and abstract, full-text articles were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. An effort was made to contact the authors for sources that were deemed relevant but were not available through university libraries. Throughout the screening process, three reviewers (NO, VP, EL) met to discuss any doubts about the eligibility of some sources.

Stage 4: Charting the data

The data were charted and extracted from the selected literature using a ‘descriptive-analytical’ approach, meaning that an analytical framework was used to gather information from each source (Arksey and O'Malley, Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005). For this step, the first author (NO) carefully analysed and used charts in Microsoft Excel grids devised by the research team. The charting form included general information about the sources (e.g. authors, title, year of publication, study type and location), the type of animal (when mentioned) and a framework of broad categories pertaining to psychological, physical, social and functional outcomes. Functional outcomes included any information regarding daily occupations, routines or areas of everyday living. To ensure a rigorous process, another member of the research team (FM) independently extracted 20 per cent of the total sources. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with the principal investigator (VP). Charting was based on the results of the studies or the key issues and themes in the aforementioned psycho-social, physical and functional categories, regardless of whether the outcomes were positive or negative. In studies that contained mixed populations (e.g. children and older adults) or mixed locations (e.g. residing in nursing homes/long-term care facilities and in the community), only data explicitly relating to older adults and community-dwelling older adults were extracted. After the data were charted, three researchers (NO, VP, EL) met to discuss and review the selected articles, and to reach a consensus consistent with the research question and the purpose of this study. In line with the aim of a scoping review, which is to present an overview of all material, the types of studies were charted.

Stage 5: Collating, summarising and reporting results

Thematic analysis (Paillé and Mucchielli, Reference Paillé and Mucchielli2012) was used to map the pros and cons of taking care of an animal for community-dwelling older adults. Two tables showing the pros and cons were produced, with each including the above-mentioned categories (psycho-social, physical and functional). The sources were then categorised according to recurring themes in the charted outcomes and according to whether the results did or did not support or were equivocal with respect to the main pros and cons. This approach allowed dominant themes and sub-themes to emerge by analysing consistent overlaps. Finally, a numerical analysis of the charted data pointed up similarities, differences and gaps in the research.

Findings

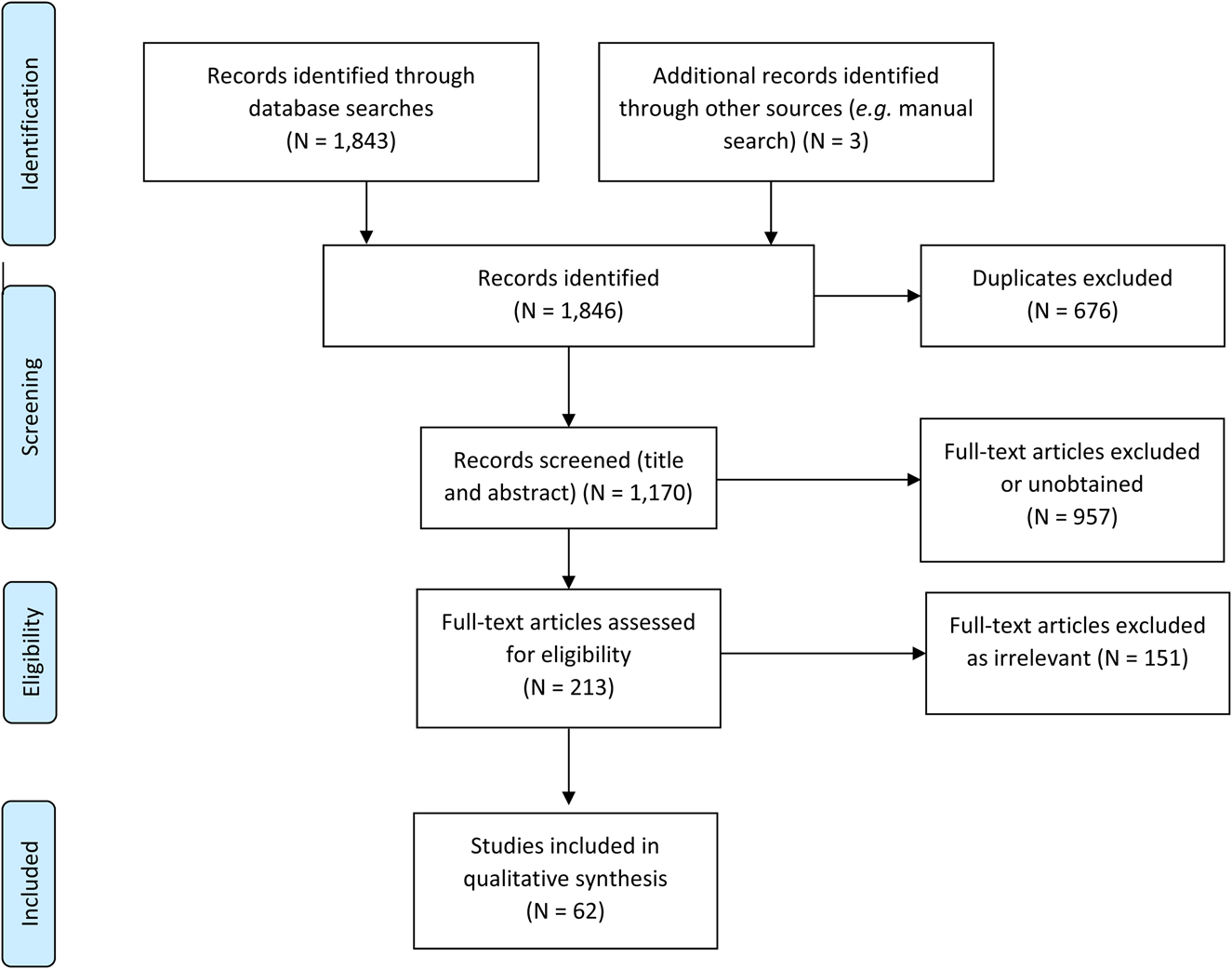

Results of the systematic search and selection process are shown in Figure 1. The searches produced a total of 1,843 abstracts from the ten databases. After duplicates were removed, 1,170 original abstracts were screened and 213 full texts were evaluated for inclusion. Of the 62 sources included in this scoping review, 24 were descriptive studies (e.g. cross-sectional or longitudinal designs) (38.8%), five were literature reviews (8.1%), 17 were from the grey literature (27.4%), 14 were qualitative studies (22.6%), one was an empirical study (1.6%) and one was a pre–post experimental design (1.6%); no authors’ opinions or systematic reviews were found. The pros and cons associated with owning companion animals were classified according to whether they were psycho-social, physical or functional outcomes (see Table 2).

Figure 1. Selection process flowchart.

Table 2. Pros and cons of pet ownership identified by community-dwelling elderly

Pros

Psychological outcomes

Positive psychological outcomes such as increased feelings of wellbeing, self-efficacy, happiness, cheerfulness and relaxation were reported in almost half the studies reviewed (N = 27; 43.5%), as well as a decrease in depressive symptoms, anxiety and stress levels (Enders-Slegers, Reference Enders-Slegers, Podberscek, Paul and Serpell2000; Hecht et al., Reference Hecht, McMillin and Silverman2001; Suthers-McCabe, Reference Suthers-McCabe2001; Becker and Morton, Reference Becker and Morton2002; Likourezos et al., Reference Likourezos, Burack and Lantz2002; VanZile, Reference VanZile2004; Mallia, Reference Mallia2006; Motooka et al., Reference Motooka, Koike, Yokoyama and Kennedy2006; Tatschl et al., Reference Tatschl, Finsterer and Stöllberger2006; Chur-Hansen et al., Reference Chur-Hansen, Winefield and Beckwith2008; de Guzman et al., Reference de Guzman, Cucueco, Cuenco, Cunanan, Dabandan and Dacanay2009; Hargrave, Reference Hargrave2011; Culbertson, Reference Culbertson2013; Gretebeck et al., Reference Gretebeck, Radius, Black, Gretebeck, Ziemba and Glickman2013; Himsworth and Rock, Reference Himsworth and Rock2013; Putney, Reference Putney2013, Reference Putney2014; Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Ahlström and Jönsson2014; McNicholas, Reference McNicholas2014; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Trigg, Godber and Brown2015; Mayo Clinic, 2015; Zane, Reference Zane2015; Branson et al., Reference Branson, Boss, Cron and Kang2016; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Lee and Tsao2017). Pets could also decrease the stress associated with grief following the loss of a loved one (Wells and Rodi, Reference Wells and Rodi2000; Suthers-McCabe, Reference Suthers-McCabe2001; Dice, Reference Dice2002; Hara, Reference Hara2007; Culbertson, Reference Culbertson2013; Putney, Reference Putney2013; McNicholas, Reference McNicholas2014; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Lord, Hill and McCune2015). Almost half of the studies (N = 30; 48.4%) also reported benefits relating to the social dimension, such as pets being a source of unconditional love and reducing the feelings of loneliness and isolation by providing companionship and/or fulfilling the need to feel needed (Wells and Rodi, Reference Wells and Rodi2000; VanZile, Reference VanZile2004; Hara, Reference Hara2007; Scheibeck et al., Reference Scheibeck, Pallauf, Stellwag and Seeberger2011; Shibata et al., Reference Shibata, Oka, Inoue, Christian, Kitabatake and Shimomitsu2012; Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Ahlström and Jönsson2014; McNicholas, Reference McNicholas2014; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Conwell, Bowen and Van Orden2014; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Trigg, Godber and Brown2015). According to Stanley et al. (Reference Stanley, Conwell, Bowen and Van Orden2014), this was especially true for community-dwelling older adults who lived alone. In addition to these direct social effects of a companion animal, many studies (N = 19; 30.6%) also reported that pets could act as social facilitators that increased social interactions, either by creating more opportunities for them or by increasing the owner's perception of sociability (Likourezos et al., Reference Likourezos, Burack and Lantz2002; Parslow et al., Reference Parslow, Jorm, Christensen, Rodgers and Jacomb2005; Hara, Reference Hara2007; Scheibeck et al., Reference Scheibeck, Pallauf, Stellwag and Seeberger2011; Shibata et al., Reference Shibata, Oka, Inoue, Christian, Kitabatake and Shimomitsu2012; Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Ahlström and Jönsson2014; McNicholas, Reference McNicholas2014; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Trigg, Godber and Brown2015). For older adults with limited social support during a crisis, it was also reported that the psychological wellbeing of those who owned a pet was less likely to decline (Raina et al., Reference Raina, Waltner-Toews, Bonnett, Woodward and Abernathy1999). Pets could also motivate their owners to overcome barriers encountered during exercise such as psychological and physical challenges (Gretebeck et al., Reference Gretebeck, Radius, Black, Gretebeck, Ziemba and Glickman2013; Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Ahlström and Jönsson2014). Finally, according to some studies (N = 12; 19.4%), aged pet owners felt safer because of their companion animals (Wells and Rodi, Reference Wells and Rodi2000; Becker and Morton, Reference Becker and Morton2002; Likourezos et al., Reference Likourezos, Burack and Lantz2002; Shibata et al., Reference Shibata, Oka, Inoue, Christian, Kitabatake and Shimomitsu2012; Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Ahlström and Jönsson2014; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Trigg, Godber and Brown2015).

Physical outcomes

Three main outcomes associated with the physical dimension were reported when comparing senior pet owners with senior non-pet owners. First, almost half (N = 26; 41.9%) of the studies reported an increase in physical activity or walking (Wells and Rodi, Reference Wells and Rodi2000; Likourezos et al., Reference Likourezos, Burack and Lantz2002; Thorpe et al., Reference Thorpe, Simonsick, Brach, Ayonayon, Satterfield, Harris, Garcia and Kritchevsky2006; Hara, Reference Hara2007; Rijken and van Beek, Reference Rijken and van Beek2011; Scheibeck et al., Reference Scheibeck, Pallauf, Stellwag and Seeberger2011; Shibata et al., Reference Shibata, Oka, Inoue, Christian, Kitabatake and Shimomitsu2012; Gretebeck et al., Reference Gretebeck, Radius, Black, Gretebeck, Ziemba and Glickman2013; Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Ahlström and Jönsson2014). Second, physical health outcomes such as improved cardiovascular health, better functional capacity one year after a myocardial infarction and lower Body Mass Index and blood pressure (Likourezos et al., Reference Likourezos, Burack and Lantz2002; VanZile, Reference VanZile2004; Ruzic et al., Reference Ruzic, Miletic, Ruzic, Persic and Laskarin2011) were identified. Third, physiological effects such as a release of biochemicals like dopamine or oxytocin into the bloodstream or a rise in parasympathetic neural activity were reported (Becker and Morton, Reference Becker and Morton2002; Motooka et al., Reference Motooka, Koike, Yokoyama and Kennedy2006).

Functional outcomes

Regarding the functional dimension, about one-quarter of the sources (N = 15; 24.4%) referred to companion animals as giving their owner's lives a sense of purpose or meaning (Suthers-McCabe, Reference Suthers-McCabe2001; VanZile, Reference VanZile2004; Chur-Hansen et al., Reference Chur-Hansen, Winefield and Beckwith2009; de Guzman et al., Reference de Guzman, Cucueco, Cuenco, Cunanan, Dabandan and Dacanay2009; Mather, Reference Mather2009; Scheibeck et al., Reference Scheibeck, Pallauf, Stellwag and Seeberger2011; Putney, Reference Putney2013, Reference Putney2014; Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Ahlström and Jönsson2014; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Conwell, Bowen and Van Orden2014; Zane, Reference Zane2015; Volkmann, Reference Volkmann2016; Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017; While, Reference While2017; Williams, Reference Williams2018). For example, taking care of the animal was reported as being an opportunity to care and be responsible for another living being. Some studies (N = 12; 19.4%) explored functional results (i.e. related to daily activities and functional abilities) associated with taking care of a companion animal. They reported that pets either maintained or enhanced activities of daily living such as light or heavy housework and functional abilities (Raina et al., Reference Raina, Waltner-Toews, Bonnett, Woodward and Abernathy1999; Gretebeck et al., Reference Gretebeck, Radius, Black, Gretebeck, Ziemba and Glickman2013), while another study (Hara, Reference Hara2007) reported that owning a pet promoted independence in older adults. However, some studies also reported that the maintenance of functional abilities was true only for dog owners who walked their dogs (Gretebeck et al., Reference Gretebeck, Radius, Black, Gretebeck, Ziemba and Glickman2013) and performing tasks involving functional abilities remained more difficult for dog owners who did not walk their dogs. It was also noted that companion animals encouraged a daily routine and added structure to the owners’ day (Becker and Morton, Reference Becker and Morton2002; Likourezos et al., Reference Likourezos, Burack and Lantz2002; Scheibeck et al., Reference Scheibeck, Pallauf, Stellwag and Seeberger2011). Finally, pets could also influence certain daily activities, such as decreasing medication use (Wells and Rodi, Reference Wells and Rodi2000).

Cons

Psychological outcomes

The possible cons of pet ownership for older adults pertaining to the psychological dimension included grief after the pet's passing (Wells and Rodi, Reference Wells and Rodi2000; Hara, Reference Hara2007; Scheibeck et al., Reference Scheibeck, Pallauf, Stellwag and Seeberger2011; Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Ahlström and Jönsson2014; McNicholas, Reference McNicholas2014) and the responsibilities surrounding pet care that were perceived as a chore, tying the owner down and creating competing demands on time and energy (Chur-Hansen et al., Reference Chur-Hansen, Winefield and Beckwith2008). Also, it was reported that pets may cause stress and anxiety if the pet owner worries about the animal (Nunnelee, Reference Nunnelee2006; Hara, Reference Hara2007; Pohnert, Reference Pohnert2010; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Trigg, Godber and Brown2015).

Physical outcomes

As for the physical dimension, ten studies (16.1%) reported that some pets increased the risk of falls (Kurrle et al., Reference Kurrle, Day and Cameron2004; Thorpe et al., Reference Thorpe, Simonsick, Brach, Ayonayon, Satterfield, Harris, Garcia and Kritchevsky2006; Chur-Hansen et al., Reference Chur-Hansen, Winefield and Beckwith2008; Pohnert, Reference Pohnert2010; Stevens et al., Reference Stevens, Teh and Haileyesus2010); Pohnert (Reference Pohnert2010) added that this was true only for dogs while, according to Thorpe et al. (Reference Thorpe, Simonsick, Brach, Ayonayon, Satterfield, Harris, Garcia and Kritchevsky2006), this was true only for cats. Other cons reported were that taking care of a pet could be physically demanding for an older person or that the animal could injure its owner (Raina et al., Reference Raina, Waltner-Toews, Bonnett, Woodward and Abernathy1999; Tatschl et al., Reference Tatschl, Finsterer and Stöllberger2006; Hara, Reference Hara2007; Chur-Hansen et al., Reference Chur-Hansen, Winefield and Beckwith2008; Hargrave, Reference Hargrave2011; Mayo Clinic, 2015).

Functional outcomes

For the functional dimension, pets could increase the risk of older adults neglecting their health or avoiding medical care for fear of losing the animal (Wells and Rodi, Reference Wells and Rodi2000; McNicholas, Reference McNicholas2014; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Conwell, Bowen and Van Orden2014). Pets could also potentially become a financial burden for the owner due to costs associated with basic pet care needs and damage to the home (Hara, Reference Hara2007). Increased medication use (Parslow et al., Reference Parslow, Jorm, Christensen, Rodgers and Jacomb2005) and use of mental health-care services (Rijken and van Beek, Reference Rijken and van Beek2011) were also found in pet owners. Greater use of mental health-care services was reported by cat owners, and the authors hypothesised that personality traits could be responsible for this effect (Rijken and van Beek, Reference Rijken and van Beek2011).

Although most studies reported the above pros or cons as key findings from their studies, nine studies (14.5%) had some equivocal findings related to the different reported psycho-social, physical and functional outcomes; in other words, it could not be determined if pets had positive or negative impacts on pet owners (Raina et al., Reference Raina, Waltner-Toews, Bonnett, Woodward and Abernathy1999; Simons et al., Reference Simons, Simons, McCallum and Friedlander2000; Wells and Rodi, Reference Wells and Rodi2000; Pachana et al., Reference Pachana, Ford, Andrew and Dobson2005; Nunnelee, Reference Nunnelee2006; Rijken and van Beek, Reference Rijken and van Beek2011; Shibata et al., Reference Shibata, Oka, Inoue, Christian, Kitabatake and Shimomitsu2012; Gretebeck et al., Reference Gretebeck, Radius, Black, Gretebeck, Ziemba and Glickman2013).

Discussion

Many of the studies included in this scoping review identified a variety of potential benefits of pet ownership for older adults, especially associated with psycho-social and physical dimensions. Companion animals were also found to be social facilitators and increase interactions with others. However, an in-depth exploration of these findings through a systematic review is needed to assess the magnitude of the effects of pet ownership in older adults on these outcomes. Concerning potential cons associated with pet ownership, less research has been done specifically on this topic. Nonetheless, grief over losing a pet and the responsibilities stemming from pet care were the most frequent negative outcomes mentioned. For more complex negative outcomes such as neglecting one's health (e.g. refusing medical services) or increasing the risk of falling, the context (e.g. animal species, activity carried out with the animal) was typically less well documented. Older adults may unintentionally neglect their own or their animal's needs for various reasons, such as the costs, physical limitations associated with ageing (Hara, Reference Hara2007) or cognitive decline (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Simon, Wilson, Mendes de Leon, Rajan and Evans2010). They may also avoid or reject medical care recommendations for fear of leaving their pet behind in the event of a relocation (McNicholas, Reference McNicholas2014). However, strategies aimed at supporting the ageing population include aligning health systems with the needs of older populations (World Health Organization, 2017), which should also include considering the importance of pets for senior pet owners. From this perspective, qualitative studies exploring the views of health professionals (e.g. nurses, veterinarians) or community agencies likely to interact with older adults and pets were scarce; in fact, only one study was found that documented this perspective (Toohey et al., Reference Toohey, Hewson, Adams and Rock2017). Concerning the desire to age-in-place, the feeling of enhanced security provided by the pet (e.g. fire risk, theft) (Wells and Rodi, Reference Wells and Rodi2000; Becker and Morton, Reference Becker and Morton2002; Hara, Reference Hara2007; Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Ahlström and Jönsson2014) may be especially important for this population (Talarska et al., Reference Talarska, Kropińska, Strugala, Szewczyczak, Tobis and Wieczorowska-Tobis2017) because ageing is often accompanied by greater perceived vulnerability and declining sensory functions (e.g. smell, sight, hearing) (Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Cruickshanks, Klein, Klein, Schubert and Wiley2009; Correia et al., Reference Correia, Lopez, Wroblewski, Huisingh-Scheetz, Kern, Chen, Schumm, Dale, McClintock and Pinto2016). Whether the mere presence of the pet induces a feeling of security or whether it objectively reduces safety risks (fire, robbery) warrants further study.

Furthermore, few studies explored pet ownership and its daily implications as a central theme and the effect it has of creating a routine and structuring older pet owners’ daily lives. Although it was reported that pets add meaning to older adults’ lives and create the opportunity to provide meaningful care – sometimes with pets even being referred to as their children (VanZile, Reference VanZile2004; Pachana et al., Reference Pachana, Ford, Andrew and Dobson2005; Scheibeck et al., Reference Scheibeck, Pallauf, Stellwag and Seeberger2011; Johansson et al., Reference Johansson, Ahlström and Jönsson2014; McNicholas, Reference McNicholas2014; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Conwell, Bowen and Van Orden2014), companion animals may have greater added value in daily life as they play a bigger and more active role as members of a household system. For example, as their basic daily needs (e.g. feeding, walking, grooming, medical care) help to incorporate rhythm and structure, pets may be especially important for older adults with fewer external structures following the loss of some occupations such as work organising their daily lives (Rosenkoetter, Reference Rosenkoetter1991; Becker and Morton, Reference Becker and Morton2002; Likourezos et al., Reference Likourezos, Burack and Lantz2002; Scheibeck et al., Reference Scheibeck, Pallauf, Stellwag and Seeberger2011). Companion animals require attention and older adults must tend to their wellbeing and be able to care for their pet, thus creating purpose and the impetus to carry out activities like eating, taking walks or tending to their own health (Rosenkoetter, Reference Rosenkoetter1991; Becker and Morton, Reference Becker and Morton2002). This in turn ensures a concrete use of time and may even encourage social participation and influence the social network and spaces frequented (Rosenkoetter, Reference Rosenkoetter1991; Chur-Hansen et al., Reference Chur-Hansen, Winefield and Beckwith2008; Degeling and Rock, Reference Degeling and Rock2013). Routines may promote wellbeing and quality of life in older adults (Ludwig, Reference Ludwig1997; Clark, Reference Clark2000), and further research is warranted to explore pet care as a promising way to maintain functional status or prevent functional decline in the frailest population.

According to our results, few studies explored the simultaneous balance between the pros and cons associated with pet ownership by older adults and how this population manages pet care despite the possible risks or physical limitations they may encounter (McNicholas et al., Reference McNicholas, Gilbey, Rennie, Ahmedzai, Dono and Ormerod2005; Hara, Reference Hara2007; Chur-Hansen et al., Reference Chur-Hansen, Winefield and Beckwith2008; McNicholas, Reference McNicholas2014). To design appropriate pet care interventions aimed at promoting community-dwelling older adults’ autonomy and safety, it is crucial to recognise the potential benefits of pet care for older adults and its associated risks. Striking this delicate balance between the pros and cons will ensure that interventions support engagement in meaningful activities while lessening the risks for older adult owners and their pets (McNicholas et al., Reference McNicholas, Gilbey, Rennie, Ahmedzai, Dono and Ormerod2005). For example, interventions could be developed (e.g. delivering pet food to reduce costs, creating educational groups on pet care) to enable older adults to pursue pet ownership and to age-in-place for as long as possible (Nunnelee, Reference Nunnelee2006). Moreover, pet care requirements may differ according to the characteristics of the environment, the person and the pet itself, which are important factors to consider for older adults who want to own or continue to own pets (Adamelli et al., Reference Adamelli, Marinelli, Normando and Bono2005; Marinelli et al., Reference Marinelli, Adamelli, Normando and Bono2007; Curb et al., Reference Curb, Abramson, Grice and Kennison2013; Johnson and Bibbo, Reference Johnson, Bibbo and Fine2015). For example, the type, age and needs of the animal may influence the benefits and risks because the outcomes may depend on the type of animal involved as well as the activities carried out with them; dogs and cats both provide companionship but have different walking needs (Simons et al., Reference Simons, Simons, McCallum and Friedlander2000; Rijken and van Beek, Reference Rijken and van Beek2011; Shibata et al., Reference Shibata, Oka, Inoue, Christian, Kitabatake and Shimomitsu2012; Gretebeck et al., Reference Gretebeck, Radius, Black, Gretebeck, Ziemba and Glickman2013). Careful examination of these factors during clinical assessments is important to ensure an optimal fit between the needs of the carer and the characteristics of the pet, which may help to reduce adverse outcomes while maximising the benefits of pet ownership for older adults.

Study strengths and limitations

This study included data sources pertaining to all pets (without focusing on one kind or species) and the grey literature (e.g. theses, books), which extended the scope of the review. The process was rigorous, including partial co-validation by co-authors to select and chart the data, and guidance by two librarians and researchers who had experience with scoping reviews. It is possible that not all studies were identified because of the huge amount of research pertaining to animals. However, the search strategy was broad and study selection was more inclusive than exclusive, which may have helped to identify more relevant studies. Finally, the optional stage 6 recommended by Arksey and O'Malley (Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005) and Levac et al. (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010) was not completed. However, a contact was established with an interested clinician for future studies.

Conclusion

Companion animals could be a promising strategy to sustain independence in community-dwelling older adults because of their multidimensional contributions to daily life and their potential to add meaning and impetus for daily activities. They provide unique benefits that are difficult to create with technology-based strategies, such as an emotional connection and attachment to a living being, as well as their ability to adapt to the evolving needs of older adults while ageing themselves. Some studies reported that the level of attachment to the animal influenced the outcomes documented (Likourezos et al., Reference Likourezos, Burack and Lantz2002; Chur-Hansen et al., Reference Chur-Hansen, Stern and Winefield2010; Shibata et al., Reference Shibata, Oka, Inoue, Christian, Kitabatake and Shimomitsu2012). Thus, learning more about the circumstances in which adverse outcomes such as falls occurred may provide insight into ways to make pet care for older adults as safe as possible (McNicholas et al., Reference McNicholas, Gilbey, Rennie, Ahmedzai, Dono and Ormerod2005).

Considering that many older adults live alone and pet ownership among older adults is common, further research is needed on this relevant topic. This review identified gaps in the literature, pointing up the need to conduct primary research to gain a better understanding of the influence of companion animals on older adults’ daily lives (e.g. structure, routine), the circumstances in which undesirable events (e.g. falls, health-care neglect) occur, and the meaning behind pet care. Since health professionals and community-dwelling older adults may have differing perceptions of acceptable risks, studies documenting the viewpoints of different actors may provide a unique analysis of the perceived balance between the pros and cons of pet ownership in community-dwelling older adults.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Francis Lacasse and Kathy Rose, Masters of Information Science, for their help in developing rigorous search strategies; Bernadette Wilson and Siniša Obradović for the English revision of the article; and the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences of the Université de Sherbrooke for financial support.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences of the Université de Sherbrooke (summer fellowship and start-up funds).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.