Introduction

The use of photography for conducting research has its roots in anthropology (Collier, Reference Collier1957; Collier and Collier, Reference Collier and Collier1986). Anthropologists set out to capture images during their fieldwork using photography. Later, researchers started to use photographs as a way to facilitate dialogue with their participants (Prosser and Schwartz, Reference Prosser, Schwartz and Prosser1998). They noticed that this approach helped to trigger participant memories and reduce fatigue, repetition and misunderstandings, therewith improving communication and interaction between researcher and participant (Collier, Reference Collier1957; Collier and Collier, Reference Collier and Collier1986). In more recent research, participants themselves are asked to capture images, meaning that photographs are taken from a more ‘emic’ (insider) perspective (Lal et al., Reference Lal, Jarus and Suto2012).

Researchers have used photography for different purposes, in different ways and with different focus. Various approaches that use photography as a main element of data collection are referred to as: photovoice, photo-elicitation, auto-photography, hermeneutic photography, auto-driving, participant photography, participatory photographic research and photo novella (Lal et al., Reference Lal, Jarus and Suto2012; Wang and Burris, Reference Wang and Burris1997). These different terms that reflect how photography is used in research in fact reflect such factors as the discipline of the researcher, the theoretical framework to which the researcher adheres (e.g. hermeneutic photography, visual grounded theory), how photography is used (e.g. ‘for eliciting interviews’, stimulating discussion, exploring a particular topic) and also who is taking the photographs (e.g. participants, researcher).

Among these different visual-based approaches photovoice is exceptional in the sense that it is associated with a well-developed, replicated and established framework that incorporates participatory research principles (Wang and Burris, Reference Wang and Burris1994, Reference Wang and Burris1997; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Yi, Tao and Carovano1998; Lal et al., Reference Lal, Jarus and Suto2012). Photovoice is a photographic technique that is based on the participatory research of Wang and Burris (Reference Wang and Burris1997). They developed photovoice as a participatory action and health promotion research tool while working at the women's reproductive health and development programme with rural women in China. Rural women were asked to take the photographs of the spirit of the village women's everyday lives: their homes, the village or environment in which they work, play, worry and love (Wang and Burris, Reference Wang and Burris1994, Reference Wang and Burris1997).

Basically, photovoice is a qualitative visual research method that refers to photographs taken by the participants and these photographs are used to explore and address community needs, strengths and challenges, stimulate individual empowerment and create critical dialogue to advocate community change (Wang and Redwood-Jones, Reference Wang and Redwood-Jones2001; Hergenrather, Reference Hergenrather2009; Sanon et al., Reference Sanon, Evans-Agnew and Boutain2014). It has been used with different age groups and populations, for example, with children (Fitzgerald et al., Reference Fitzgerald, Bunde-Birouste and Webster2009; Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Frohlich and Fusco2014; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Savahl and Fattore2017), youth (Collins et al., Reference Collins, Baiardi, Tate and Rouen2015; Heslop et al., Reference Heslop, Burns, Lobo and McConigley2017), middle-aged persons (Flum et al., Reference Flum, Siqueira, DeCaro and Redway2010; Kingery et al., Reference Kingery, Naanyu, Allen and Patel2016), care-givers (Garner and Faucher, Reference Garner and Faucher2014; Angelo and Egan, Reference Angelo and Egan2015), immigrants (Adekeye et al., Reference Adekeye, Kimbrough, Obafemi and Strack2014; Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Dean, Kirkpatrick, Berbary and Scott2016), people with intellectual disabilities (Jurkowski, Reference Jurkowski2008; Jurkowski et al., Reference Heslop, Burns, Lobo and McConigley2009; Akkerman et al., Reference Akkerman, Janssen, Kef and Meininger2014), persons with mental illness (Cabassa et al., Reference Cabassa, Nicasio and Whitley2013a, Reference Cabassa, Parcesepe, Nicasio, Baxter, Tsemberis and Lewis-Fernandez2013b) and indigenous groups (Castleden and Garvin, Reference Castleden and Garvin2008; Huu-ay-aht First Nation, Reference Castleden and Garvin2008; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Ingham, Cram, Dean and Davies2013). Photovoice has also been used to examine and explore various issues such as chronic health problems, community health assessment and promotion (Allotey et al., Reference Allotey, Reidpath, Kouame and Cummins2003; Oliffe and Bottorff, Reference Oliffe and Bottorff2007), political violence (Lykes et al., Reference Lykes, Blanche and Hamber2003) and discrimination (Graziano, Reference Graziano2004), nutrition and dietetic research (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Garcia and Leipert2010), and cancer and work experiences (Morrison and Thomas, Reference Morrison and Thomas2014, Reference Morrison and Thomas2015a, Reference Morrison and Thomas2015b).

Clearly, many researchers have seen the benefits of photovoice for their studies. Among the advantages in using the method for research are involvement, empowerment and engagement of participants, giving voice to participants, the stimulation of reflections, and in-depth exploration of perspectives and experiences of participants. These advantages would also apply to qualitative research with older adults, in theory, who can be empowered to share their experiences, engage in dialogue, and feel supported and encouraged by other participants.

There have been a number of studies that discussed the use of photovoice with older persons in different research contexts (Baker and Wang, Reference Baker and Wang2006; Blair and Minkler, Reference Blair and Minkler2009; Andonian and MacRae, Reference Andonian and MacRae2011; Mahmood et al., Reference Mahmood, Chaudhury, Michael, Campo, Hay and Sarte2012; Annear et al., Reference Annear, Cushman, Gidlow, Keeling, Wilkinson and Hopkins2014; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Chan, Chan, Cheung and Lee2016; Lewinson and Esnard, Reference Lewinson and Esnard2015). One review discussed general literature on this approach in public health (Catalani and Minkler, Reference Catalani and Minkler2010). Other studies and reviews focused on methodological strengths and issues of using the photovoice method and participant action research with older adults (Blair and Minkler, Reference Blair and Minkler2009; Novek et al., Reference Novek, Morris-Oswald and Menec2012). The main conclusions coming out of these studies were that photovoice was considered an effective tool for eliciting older persons’ perceptions of their communities. However, some challenges should be take into account while using photovoice. Emphasis was put on the value of involving older persons in participatory action research, both for the scientific discipline of gerontology, as well as for older persons themselves.

Yet, existing studies that incorporated the photovoice method with older people have been mostly descriptive, lacking in-depth exploration and analysis of strengths and limitations of the photovoice method. The use of photovoice in older populations requires its own study of approaches, techniques and challenges. Often older persons may be under-represented in research studies and sometimes occupy marginalised positions in society. Therefore using photovoice, with its roots in empowerment, education and feminist theory, may be especially suited to elicit seniors’ perspectives and their role in research projects because it gives them the opportunity to speak out and share their own stories and experiences.

However, it is important to remember that older participants may be more likely to experience mobility or visual problems and/or other compromised abilities, which may hamper the feasibility of the method. Functional limitations and the frailty of participants are aspects that should be taken into account and thus can need special adjustments or modifications in using the method with older persons, or could even be barriers to implementing the method in certain situations.

The purpose of this study is to review existing studies using photovoice with older participants specifically, to consider its potential as a qualitative research method in the field of gerontology. We discuss the advantages, but also possible limitations and challenges of the photovoice method with older persons in order to provide guidelines for and to aid researchers in improving the design of their future photovoice studies.

Methods

Identification of studies

Studies were identified by searches of twelve databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Web of Science, CINAHL, Academic Search Premier, ScienceDirect, Wiley-Blackwell, LWW, Taylor & Francis/Informa, ERIC and COCHRANE). The search strategy consisted of the AND combination of two concepts: ‘photovoice’, ‘older adults’. For these concepts, all relevant keyword variations were used, not only keyword variations in the controlled vocabularies of the various databases, but the free text word variations of these concepts as well (such as photovoice method/approach, participant-generated photographs, photo-elicitation, participatory action research, photovoice methodology, photographs, older persons/people, elderly, seniors). Because of the usage of different terms that can actually refer to the same method by various studies, we have also included in our search strategy such terms as ‘photovoice’, ‘photo-elicitation’, ‘photography’, ‘participant-generated photos’ and ‘photo novella’ in order not to miss any relevant studies.

Searches were restricted to papers published in English. The bibliographies of relevant original and review articles (and two dissertations) were screened for additional studies, manuscripts or books that were not identified in our literature search. Both authors screened the titles and abstracts of all articles that were identified by the search. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were retrieved and assessed.

Inclusion of studies

Empirical studies that applied the photovoice method in research with older people were included in the current review. Moreover, other research papers and editorials that discussed the application of the method in older adults were also retained, as these could inform the discussion about the benefits and limitations of the method. Persons were considered ‘older’ when they were defined as such by the study itself, regardless of the age range of the participants.

Analysis of the studies

Analysis of studies began with the development of a descriptive coding scheme (Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1990), including such categories as purpose of the study, participant characteristics (age, gender), objects or situations that were photographed, cameras used and period of photograph taking (type of camera, duration) and the method of data collection used together with photovoice.

Each article was systematically reviewed and analysed by labelling the text corresponding to the categories mentioned above. Detailed summaries of each article (based on the categories) were produced which allowed a clear picture of the categories between and across the articles to be obtained, and which allowed these categories to be compared amongst each other between the articles. After reviewing and analysing the advantages and limitations of the use of photovoice that were encountered in different studies, we identified some main themes and sub-themes. Each time when advantage, limitation, or implication and future consideration were mentioned in the study, they were noted and coded, then they were grouped together (advantages, limitations correspondingly). Thereafter, they all were categorised and combined into sub-themes. Finally, sub-themes created bigger overarching themes on the basis of common features of the corresponding group of advantages and limitations.

Results

Results of the search

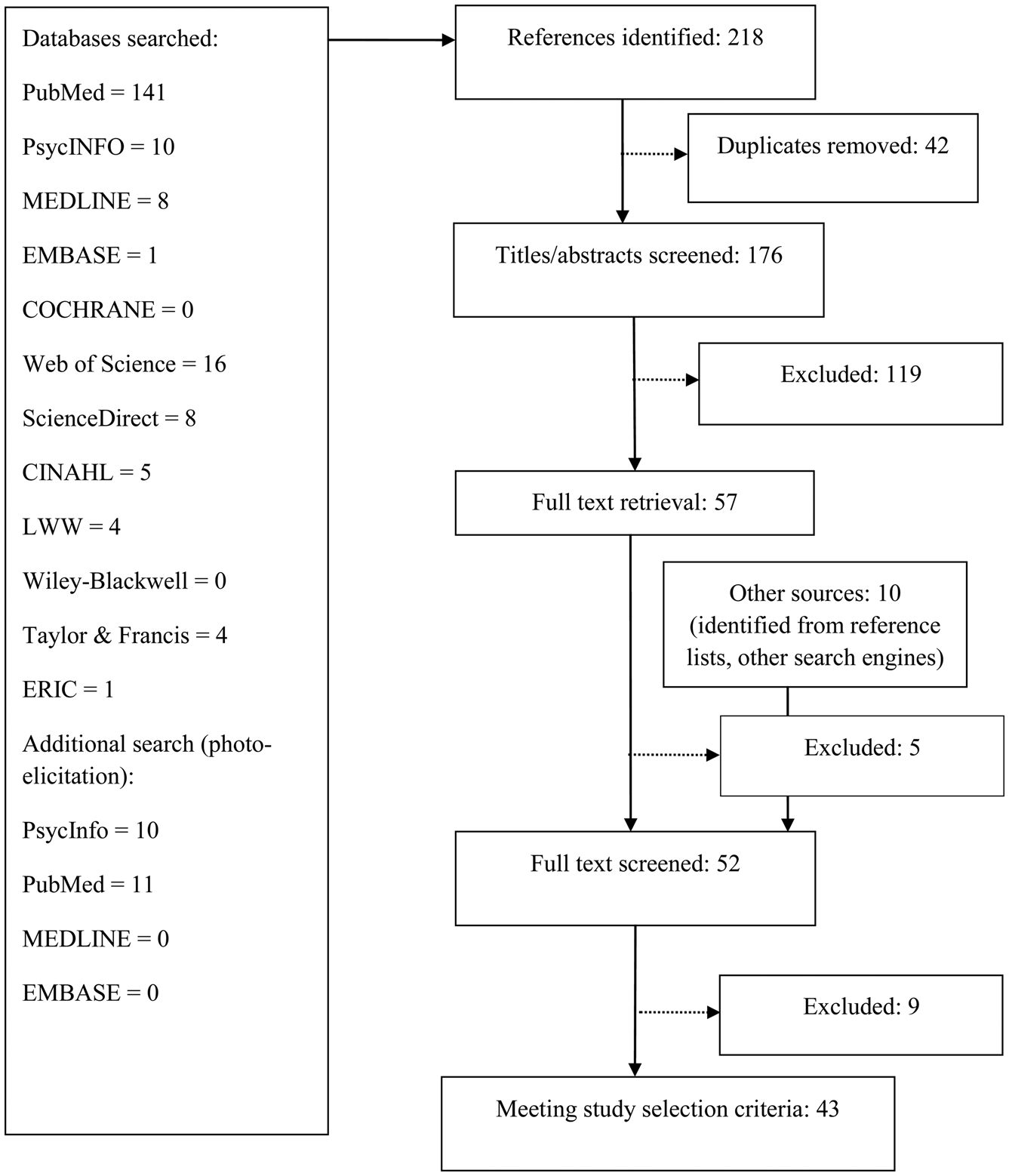

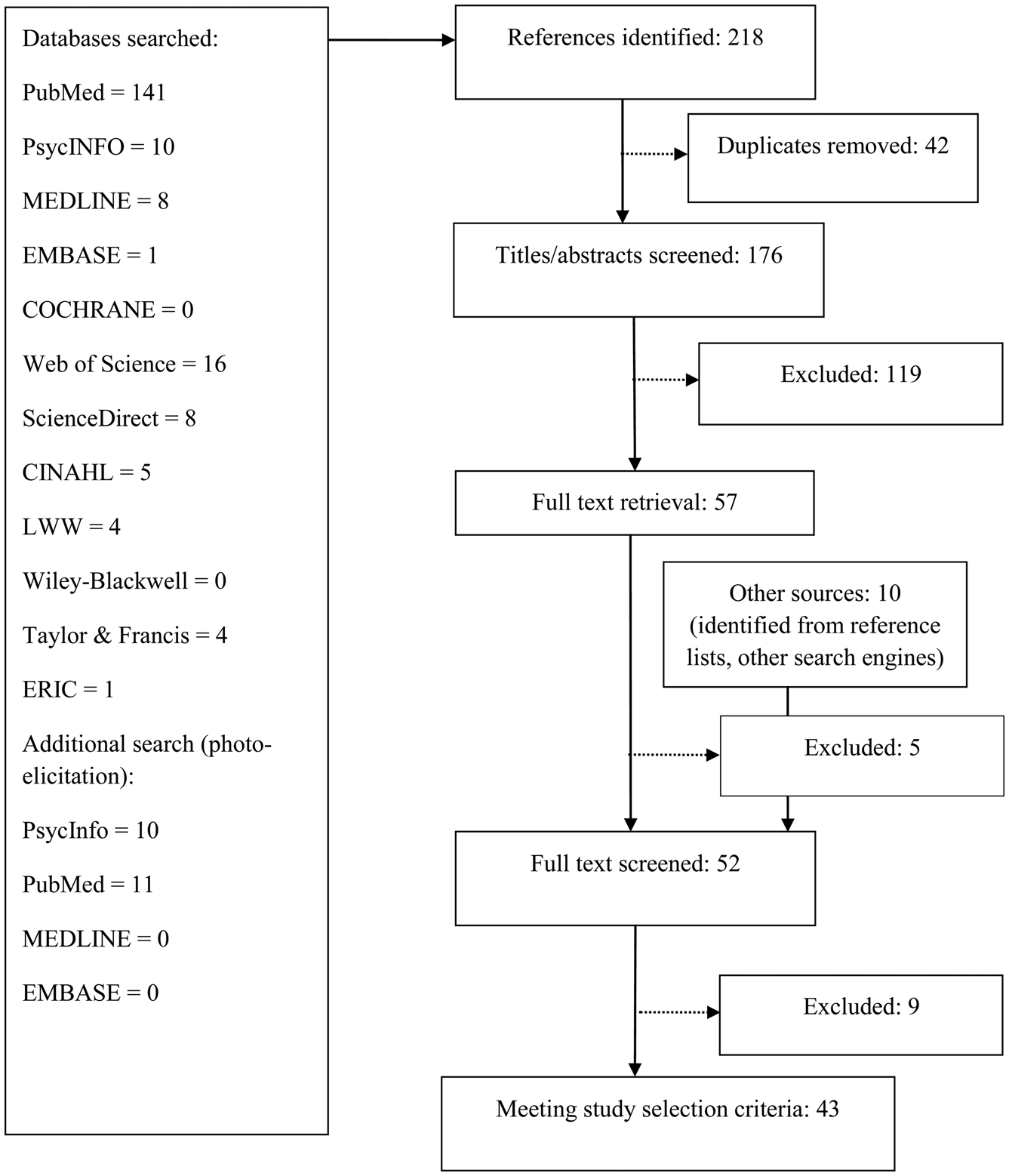

Searched databases yielded different hits (for more details, see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Literature search results flow chart.

Screening of titles and abstracts identified potentially relevant papers. For 57 articles, full texts were retrieved, however only the full texts of 52 studies were screened (the other five articles appeared not to meet the inclusion criteria). These papers were thoroughly studied and nine articles were further excluded because they did not really discuss photovoice and/or older persons were not a target group of the study. Also, during this careful screening process ten additional studies were added on the basis of reference list searches. A final selection of 43 studies which met the inclusion criteria are addressed in this review (see Figure 1).

In this review we used the term photovoice and its meaning according to how it was introduced and developed by Wang and Burris (Reference Wang and Burris1997), referring to the photographs that were produced by the participants themselves for the purpose of the particular study. The studies were included in the review if the method used in the study corresponded to the definition that was mentioned above.

Terminology

There was inconsistency in the terms used to refer to the method: ‘photovoice’, ‘auto-photography’, ‘photo-elicitation’, ‘photo novella’ and ‘participant-generated photos’. As pointed out by Tishelman et al. (Reference Tishelman, Lindqvist, Hajdarevic, Rasmussen and Goliath2016), some studies used these terms interchangeably. There were also studies that referred to these other terms when performing the photovoice method (Kohon and Carder, Reference Kohon and Carder2014; Fisher-McLean, Reference Fisher-McLean2017). Because these terms sometimes refer to different methods, which are often used for different empirical purposes, we provide a glossary of terms used. Some of them were introduced by particular scholars, or were adopted from and used in different fields (e.g. anthropology, sociology, photography, ethnography).

Photo novella was introduced by Wang and Burris (Reference Wang and Burris1994) and meant that instead of assigning the cameras to health specialists, policy makers and professional photographers, they were put into the hands of children, village women, community workers and other persons with little access to decision makers. Photo novella indicates ‘picture stories’. In their later studies Wang and Burris used the term photovoice instead (Wang and Burris, Reference Wang and Burris1997).

Photo-elicitation refers to the simple idea of inserting a photograph into a research interview to explore a particular topic. It may use any visual images, including archival photographs or those generated by the researcher or participant (Frith and Harcourt, Reference Frith and Harcourt2007). This technique was first used in research to examine how families adapted to living in a community with ethnically different people, and to new forms of work in urban factories (Collier, Reference Collier1957; Collier and Collier, Reference Collier and Collier1986). The most important question researched was the environmental basis of psychological stress (Collier, Reference Collier1957; Collier and Collier, Reference Collier and Collier1986; Harper, Reference Harper2002). According to Harper (Reference Harper2002), photo-elicitation studies have been focused on four themes: social organisation/social class, community, identity and culture.

The term ‘participant-generated or participant-produced photographs’, the same as photovoice, refers to photographs produced by the participants themselves. They have been used for generating research data with a variety of populations and agendas (e.g. nursing research, mental illness research, health-care research, studies exploring fatherhood and smoking). These photographs are used most often for exploring issues that may be difficult to speak about directly (Oliffe et al., Reference Oliffe, Bottorff, Kelly and Halpin2008; Balmer et al., Reference Balmer, Griffiths and Dunn2015; Kantrowitz-Gordon and Vandermause, 2015; Morrison and Thomas, Reference Morrison and Thomas2015a,Reference Morrison and Thomasb; Han and Oliffe, Reference Han and Oliffe2016; Tishelman et al., Reference Tishelman, Lindqvist, Hajdarevic, Rasmussen and Goliath2016).

In auto-photography participants take photographs, choosing images and representations of themselves. This method attempts to ‘see the world through someone else's eyes’ (Thomas, Reference Thomas2009: 1). In human geography, auto-photography has largely been used by researchers who studied children's geographies throughout the world (the places and spaces of children's lives) because it is an easy method for generating data and allows a self-representation from subject groups, children and youth, who may find it more difficult to express themselves verbally (Thomas, Reference Thomas2009).

Table 1 provides an overview of the studies that were identified. In the table we numerate the studies; the numeration of the studies will be used further in this review in order to make it easier for the reader to go through the studies and also to refer to the particular studies.

Table 1. Overview of studies using the photovoice method with older participants

Notes: Numeration of the studies in this review is used to make it easier for the reader to go through the studies and also to refer to the particular studies. USA: United States of America. GIS: geographic information system. ND: not defined NA: not applicable

Participants

In the majority of the studies (N = 29), the participants included both older men and women, whilst in four studies the gender of the participants was unspecified. In some studies the participants were primarily older women (N = 10). Some of the studies (N = 5) included a mixed sample, consisting of older and younger participants and/or professionals and care-givers. Several studies focused on particular issues and settings that are pertinent to older women, e.g. community-dwelling women, rural women's facilitators and barriers in acquiring and preparing food, or rural older women's health promotion needs and resources.4,5,9,23,24,34 This may reflect the fact that one of the theoretical frameworks at the root of the photovoice method is feminist theory (Wang and Burris, Reference Wang and Burris1997; Wang and Redwood-Jones, Reference Wang and Redwood-Jones2001). Other target groups that we encountered in studies included: older Latinas, older Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean and African immigrants, and older people with diabetes.11,18,30,32

Data collection

Interviews and/or focus groups were mostly used as methods of data collection together with photovoice (Table 1). Half of the studies conducted either focus groups or interviews as well as focus groups after the process of taking photographs by the participants. The rest of the studies conducted only interviews after the use of photovoice. During focus groups and interviews participants discussed photographs that best represented barriers and facilitators of physical activity,7,8,24 photographs that represented age-friendly communities,10,29 experiences of social participation19,38 and aspects of environment.24,26,40

Cameras and period of photograph taking

The majority of studies (N = 24) used disposable cameras for taking photographs. Other studies stated that digital cameras, iPads, own cameras or other types of camera were used (N = 10). Thirteen studies reported giving participants two weeks for taking photographs, with the others ranging from one week to seven months (reported in one study). The study that used photovoice during seven months was designed to establish intergenerational contacts between young, homeless women and older, independently housed women through the use of photovoice (for more details, see Table 1). During the discussion of their photographs the women established mutual respect, exercised affirmation and also built alliances. Even though the women were from different generations and had different life experiences, the sharing of photographs revealed many commonalities between them and thus helped to establish intergenerational contact.

Topics covered

Studies covered a broad range of topics, such as the meaningful aspects of people's surroundings in the last phases of life; experiences of home; environmental factors influencing walking; Latinas’ socio-cultural context relative to health; views of African immigrants on health; meaning and experience of leisure of persons with early stage memory loss; and perceptions of ‘age-friendliness’ (see Table 1).

Advantages of photovoice

Many advantages of photovoice were highlighted. These advantages could be grouped into the following themes: therapeutic effects of photovoice; enrichment of data; providing opportunity for capturing perceptions and sharing experiences; empowerment of subjects; photographs acting as facilitators for interactions and reflection; and specific advantages of photovoice (Table 2).

Table 2. Advantages of the use of photovoice

Therapeutic effects of photovoice

Photovoice was seen as facilitating catharsis and providing therapy for some participants that allowed them to express feelings and experiences that were causing them problems.4,6,22 Studies that demonstrated this advantage were exploring ageing and social and health promotion needs and resources of older rural women or the experiences of ‘home’ of older persons and their relation to health and ageing in place.4,6

At the same time, photographs provided participants with the basis to talk about difficult issues and problems, things about which they normally would not talk. Topics that were more easily addressed with photographs included physical activity opportunities and perceived barriers to physical activity; physical elements and places that symbolised crime in the neighbourhood; or images of an age-friendly community.7,11,38,39

Enrichment of data

Photovoice helped to evoke a wealth of information from older persons’ perspectives, improving the understanding of the lived experiences of the participants, and gaining an understanding of what is meaningful and important to them.4,5,19,24,26,29 By talking and discussing various issues of interest, participants also became more acquainted with them, and realised and understood things that they might not have been aware of before. Thus, photovoice helped to increase awareness of the issues that were addressed in the research.20,23,24,30,32,42

The combination of different methods such as photovoice, interviews, focus groups and participant observation was seen as particularly valuable. An example is provided by a study that examined the role of leisure activities in people with dementia (Genoe and Dupois, Reference Genoe and Dupuis2014). Combining photovoice with interviews and participant observation allowed a better understanding of the complexity of living with memory loss and how this impacted on leisure seeking. The study provided insight into the changes in leisure experiences and participants’ day-to-day experience of life with memory loss (Genoe and Dupois, Reference Genoe and Dupuis2014).

Providing opportunity for capturing perceptions and sharing experiences

Photovoice was perceived as a form of creativity, a different ‘lens’ to illustrate participants’ experiences, allowing less tangible aspects of life, such as feelings, experiences and life challenges, to be illustrated.1,4,7,8,10,15,22,26,29,38

In addition, photovoice gave tools that helped participants to share their stories with other participants or researchers.20,22,37 The camera, as a research tool, was able to get to the places that would normally not be reachable by other means and capture things that would be difficult to study using other methods only, for instance, aspects of the home, social networks and local environments.26,28,30

Empowerment of subjects

Using photovoice fostered empowerment of the participants, and enabled participation and co-learning between participants and researchers. Sharing and discussing their photographs helped participants to realise that their perspectives and experiences are important and valuable. Participants became aware that their opinions matter and can be beneficial for others.4,5,8,28,30,42

Participants supported and encouraged each other in showing and sharing their photographs, also empowering each other. High levels of interaction, empathy, compliance and engagement among them showed that they enjoyed the process and welcomed the opportunity of being together and talking about their photographs. Furthermore, involvement of the participants in the research process revealed new information, engaged them in dialogue and increased ties among the participants.4,22,24,27,32,34,36,37,42

In two studies, participants’ photographs were included in the report that was sent to political leaders and community organisations.10,42 This enabled their concerns and ideas to be brought to local policy makers and community organisations that helped to advocate for change.

At the same time, participants could control the process of taking photographs, and determine which images to discuss and analyse, and how they may be interpreted by the researchers. This enabled a more equal relationship between the participants and researchers within the research project.26,27

Photographs as facilitators of interactions and reflection

Photographs served as an archival record and memory aid that provided participants with a visual reminder and a guide during interviews and focus groups.13,27 Moreover, photographs gave participants the possibility of expressing themselves both visually and textually, facilitating the dialogue and helping to delve deeper into the issues studied and thus obtain a more comprehensive understanding of these issues.1,4,27,34,32,36,38,39 In some studies the participants were using photographs as a metaphor for their feelings about ageing, physical activity and physical self, or the relationship between social participation and physical environment.34,38

Photovoice allowed participants to reflect on their own experiences, which was influential as they could talk about the issues which were important for them or that they were concerned about. For example, experiences of home safety challenges, concerns with food access or characteristics of home environments.13,20,23,38

Specific advantages based on topic of interest and/or purpose of study

Photovoice enabled various participants to identify, define and understand better the issues that were researched in the studies, e.g. features of environment, hazards and facilitators of walking, age-friendliness, chronic pain, food access, meaning of risks, facilitators and barriers for physical activity in social and physical environments, experiences with diabetes, multigenerational links, and features of the city that contributed or prevented respect and social inclusion.8,10,17,20,21,24,26,27,30,37,38,39,42

Using photovoice for identifying environmental barriers to and facilitators of walking allowed not only specific hazards and facilitators of walking among community-dwelling older persons to be defined, but also allowed an understanding of how these factors relate to each other and to the broader environment to be gained (Lockett et al., Reference Lockett, Willis and Edwards2005). With the use of photovoice in the study on older persons’ perceptions of age-friendly communities, participants defined for themselves what age-friendliness meant and documented positive features and barriers in different settings throughout their communities (Novek and Menec, Reference Novek and Menec2014).

Other advantages

Photographs created by the participants themselves made the experience more applicable to them. Thus, photovoice was also perceived as a learning method (Breeden, Reference Breeden2016). Also, it was pointed out that photovoice is less reliant on cognitive function than other methods of data collection, like surveys, filling in diaries or questionnaires (Tishelman et al., Reference Tishelman, Lindqvist, Hajdarevic, Rasmussen and Goliath2016), which seems particularly valuable for research among vulnerable older people.

Limitations of photovoice

In this part we discuss the main limitations mentioned in the various studies included in this review. We combined them in the following categories: issues with informed consent forms; training of the participants; mobility and vision problems of the participants; feasibility issues; issues with cameras; and issues with photographs (see Table 3).

Table 3. Limitations of using photovoice method

Issues with informed consent forms

Issues with informed consent forms included refusal to sign informed consent and thus loss of potential participants, which appeared as an obstacle in many studies.5,15,29,32 Moreover, obtaining informed consent forms from people who were on the photographs was an issue which is clearly unique to using photovoice data collection.4,34 Some participants took photographs without people, as in that way they could avoid obtaining consents (Novek et al., Reference Novek, Morris-Oswald and Menec2012). This might have implied that they felt not completely free to take photographs of everything that was important to them: sometimes reluctance to obtain consents was mentioned as a reason not to include people on the photographs (Bell and Menec, Reference Bell and Menec2015).

Mobility and vision problems of the participants

Mobility and vision problems of participants, not uncommon in older adults, were sometimes limiting their participation in studies because it was hard for them to take photographs, or it was difficult to reach all places that would be considered meaningful objects for photographs. Another limitation that was closely related to the functional abilities of participants was the inability to accommodate the special needs (e.g. transportation, pain severity, physical limitations) of the participants. Due to functional problems, more vulnerable groups were sometimes excluded from the studies or were under-represented.4,15,28,39 Another limitation was that researchers had to accompany some participants, especially the ones with mobility issues, which was not always possible and/or feasible.5,29

Feasibility issues

Feasibility issues that were mentioned by researchers encompassed seasonal characteristics, logistics, investment of time, money and effort, and the need for assistance for some participants. The season in which participants took pictures influenced what was captured in photographs on occasion. For instance, for studies investigating physical activity the season in which the photographs were taken could reveal different patterns or regularities (Lockett et al., Reference Lockett, Willis and Edwards2005).

Training of the participants

Training provided to the participants was considered to be a possible limitation that could influence the results obtained, as the choice of photographs taken by the participants might be influenced by the instructions that they received during the training.7,20,30,42

Issues with cameras and photographs

Issues with cameras and photographs, such as concerns and unfamiliarity with cameras and their manuals, and the difficulties in capturing with cameras the intangible aspects of social life such as isolation and exclusion, were also mentioned in some studies. Some of the photographs with valuable meaning or insightful information were not analysed because participants did not select them for discussion or were challenging to analyse.27,29,32,36,37,38

Discussion

It appears from this review that photovoice has been used to study a wide range of topics in older people, from health issues and the impact of environment on health and wellbeing, to leisure experiences of groups living with HIV/AIDS. Also, the contexts and settings in which studies were conducted varied from rural regions in Canada and urban New Zealand to community-dwelling older persons who live in hotels. In terms of gender, in the majority of the studies (N = 29) the participants were both older men and women. In this review we have discussed the various strengths and limitations of using photovoice that were experienced by researchers. These are important for understanding better the challenges and advantages of using photovoice with older persons.

The main advantages of photovoice discussed in this review focused on its therapeutic effect for participants, enrichment of data, its ability to capture perceptions of respondents and allow them to share experiences, empowering participants, facilitating interaction, and the reflection and connection of participants.

Photovoice was perceived as a therapy for older participants, giving them the possibility to express their feelings and worries, and to discuss issues that were often unspoken. This experience is difficult to obtain by using other methods of data collection as photographs as such were guiding older persons in their stories and served as special memory aids for reflections. This advantage of photovoice was also discussed by Levin et al. (Reference Levin, Scott, Borders, Hart, Lee and Decanini2007). Levin et al. (Reference Levin, Scott, Borders, Hart, Lee and Decanini2007) emphasised that photographs can serve as an alternative to verbal and written methods, providing participants with other means of self-expression, thereby increasing opportunities to engage in the research process, which was also the case in the studies discussed in our review.

Moreover, photovoice provided diverse information and data from older participants, and at the same time allowed a better understanding of their perspectives and allowed valuable insights into their experiences and stories to be gained. Their experiences were illustrated in a different creative way, using cameras and photographs, making them more alive and real, disclosing things, aspects and places that could not be discussed and reflected on by other means or methods. This strength of photovoice was also mentioned in the study of Novek et al. (Reference Novek, Morris-Oswald and Menec2012) on the strengths and issues of using photovoice with older persons. That study examined age-friendly community characteristics by exploring older people's perceptions and views, and the ways in which they make sense of the world. The participants found a creative way to capture important less-tangible aspects of life such as social environment, independence, community history, respect and participation.

In addition, photovoice provided the opportunity for raising awareness, and helped participants to discuss their needs and issues of interest and to realise the importance of their own knowledge. These advantages are in line with the findings of other studies confirming that the discussion of the participants’ photographs made them conscious and aware of, and even critical of, their own perceptions and the issues they were facing in their daily lives (Wang and Redwood-Jones, Reference Wang and Redwood-Jones2001; Catalani and Minkler, Reference Catalani and Minkler2010; Novek et al., Reference Novek, Morris-Oswald and Menec2012).

A number of studies that we reviewed have seen empowerment, engagement, participation and involvement of older participants as one of the main advantages of the method. Older participants were able to support and empower each other by sharing their knowledge and experiences. Moreover, this brought them recognition, self-confidence and self-value. This is important for various target groups but especially for older participants as recognition of their own knowledge and valuable experiences may be crucial when older people feel more vulnerable, under-valued and less significant. Furthermore, it gives participants control over the process, by actually participating in data collection and contributing to the study.

A review on photovoice literature in public health confirmed our findings that photovoice was able to generate a social process of critical consciousness and participation, therewith facilitating empowerment, by providing opportunities for reflection, critical thinking and active engagement (Catalani and Minkler, Reference Catalani and Minkler2010). Empowerment was indeed one of the main goals of the development of the photovoice method by Wang and Burris (Reference Wang and Burris1997), emphasising that photovoice allocates visual image as a robust form of communication.

These apparent advantages of the photovoice method with older persons should stimulate and motivate researchers to conduct studies using this visual method of data collection. Moreover, as shown in this review it can be combined with other methods such as interviews, focus groups or observations. Topics of study in gerontology that may particularly benefit from including a photovoice element are, among others: aspects of physical and social environments; walkability; safety issues; aesthetics of the neighbourhood; elements of informal care-giving; and issues of trust, social participation and social isolation.

Studies in this review encountered or discussed some important limitations and challenges of applying the photovoice method. These included the frailty or special needs of older participants, unfamiliarity with the technology and the need for extra help with camera use.

One of the important limitations and challenges mentioned was the difficulty of accommodating the special needs of some participants. Moreover, the majority of studies did not include participants who had some health-related issues or older people with disabilities. It is important to point out that excluding people with special needs or participants who require extra assistance can limit the diversity of the results obtained. While using photovoice with older persons, it should be expected that participants may have special needs or require more, additional or just simply different assistance than other participants. Therefore, these issues should be taken into account during the initial planning and design of the study. Paradoxically, photovoice as a method for empowerment may lead to the exclusion of vulnerable groups of participants if studies are not designed to properly accommodate their needs.

Baker and Wang (Reference Baker and Wang2006) conducted a study with individuals who had physical limitations and transportation barriers, with whom they were unable to conduct group sessions. However, Baker and Wang solved this issue by instead carrying out an exit interview survey (final interview survey of the project) and most of the other photo-taking communication by mail. Another possible solution for the physical limitations and challenges with camera use is to have photographs taken by another person or someone from the research team, but still directed by the participant. On one hand, while collaborating with another person to take pictures may enhance participation and allow older persons with mobility issues to participate and contribute to the study; on the other hand, it may limit their independence and furthermore questions about whose perspectives may be portrayed in the photographs can be also an issue here. For instance, in the study of Novek et al. (Reference Novek, Morris-Oswald and Menec2012), research team members were available to accompany participants with the condition that the participant was in charge of the ideas captured in the photographs. This assurance of the available aid from the research team made it possible for participants with limited mobility to take part in and contribute to the study.

Issues and unfamiliarity with camera use may be addressed by devoting considerable time to explaining the instructions, letting older persons practise and ensuring that each person is comfortable using the camera. Moreover, it is possible to test the instructions and the ease of camera use beforehand with a few older persons in a pilot study.

As already mentioned, photovoice may lead to exclusion of more vulnerable older participants, instead of empowering, engaging and involving them. Groups of older people who are in danger of being excluded are those who have functional limitations and those who may be reluctant to use cameras or go out and engage with their environment to take photographs. These groups are likely to include a disproportionate share of people from lower socio-economic backgrounds, and people with mental health issues, low self-esteem and health problems. Researchers should be aware of barriers to including representatives of such vulnerable groups and, especially because photovoice may have an empowering effect on participants, should take great care to include representatives of all relevant groups in their studies. Similarly, Catalani and Minkler (Reference Catalani and Minkler2010) stressed the importance of photovoice in enabling researchers and practitioners in the public health field to reach out to isolated communities and groups in order to engage them in the meaningful research process.

In different studies, the season and weather were noted as factors which should be taken into account in future research. Conducting research in different seasons (summer and winter) and with different weather conditions may reveal different information and insights, as these factors may influence participants’ interaction with the community and with their surroundings. Indeed, some topics studied, such as patterns of physical activity, person–environment relationship, facilitators and barriers to food acquisition and preparation by rural older residents, or influences of the use of parks on healthy ageing, may change remarkably from one season to another. Longer study periods, allowing older participants to take photographs during both winter and summer, could prove much more useful.

Beyond the ethical principles that are important to consider when conducting any qualitative study, photovoice adds additional issues which need to be taken into account.

One of the most important challenges that many studies have encountered when using photovoice with older persons was the refusal to sign informed consent forms and difficulties with obtaining them from people who were captured on the photographs. This led to taking photographs without people on them or taking photographs without permission which made it impossible to use these photographs fully later on. Taking photographs of others without permission or photographs that risk showing a person, community or group in a negative light are key issues to consider when using photovoice. Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Morrel-Samuels, Hutchison, Bell and Pestronk2004) provided some valuable principles that other researchers have adopted to help minimise the ethical risks related to photovoice. These principles include differentiation between consent forms; engaging participants in education and discussion related to photography ethics; providing written material and instructions; reviewing consent for publication of photographs; and providing a copy of photographs to participants.

This review has several important strengths. It gives a comprehensive overview of the studies using photovoice with older persons, providing a clear picture of the study purpose, things that were captured by photographs, research participants and contexts, and methods of data collection used with photovoice. Moreover, it provides a thorough description and discussion of the advantages and limitations of the photovoice method with older persons.

Over the past few decades there has been an increasing interest in the use of participatory visual methods across different disciplines and within a wide range of social and geographic contexts. Researchers seek to explore social conditions and relationships, lived experiences, perceptions and views, as well as discuss the visual presentation of research findings through different means of visual media (Banks, Reference Banks2001; Catalani and Minkler, Reference Catalani and Minkler2010; Chalfen, Reference Chalfen, Margolis and Pauwels2011). This review shed light on important features and challenges of one of the participatory visual methods, i.e. photovoice, and moreover its usage with older persons. It has brought the evidence that photovoice has great potential and can be used as a participatory research tool for conducting engaging and empowering research. Thus, the findings of this review can be useful not only for the field of gerontology but also for public health and visual research in general.

Despite its strengths, there are possible limitations that should be mentioned. Although we tried to identify all existing studies that applied photovoice in research with older persons, it is possible that some studies were omitted by our search strategy. Second, the focus of our review was primarily on the method itself rather than on how the data were analysed or what the outcomes of the studies using photovoice were. Moreover, restriction to studies published in English may have led to the exclusion of studies from other countries.

Several topics that are of interest to gerontologists may benefit from a photovoice approach. For instance, photovoice would enable gerontologists to ask participants to visualise situations or contexts that they associate with experiences of elder abuse. Photovoice could elicit insightful information where feelings of guilt or shame might hamper data gathering on the basis of in-depth interviewing alone. Another example could be photovoice as a method for eliciting and contextualising older migrants experiences of adapting to their new countries and their attitudes towards and experiences with institutional health care.

Conclusion

Our review suggests that the photovoice method is a flexible tool for strengthening gerontology research. It can be altered to fit specific goals, divergent issues studied and different contexts. This study shed light on important features, limitations and challenges of photovoice, thereby increasing our knowledge and understanding of this participatory visual method with older persons.

Using photovoice, researchers can conduct engaging and empowering research which also reduces the power imbalance in ways that only interviews or focus groups do not generally manifest. Although while conducting photovoice studies it is necessary to understand that it can be practically challenging as older participants may have special needs that can differ from the ones of other target groups. Well-designed studies could overcome many of those challenges.

Financial support

This work was supported by the European Union Horizon2020 Programme (grant agreement number 667661; Promoting Mental Wellbeing in the Ageing Population – MINDMAP). The study does not necessarily reflect the Commission's views and in no way anticipates the Commission's future policy in this area.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.