Introduction

Access to affordable, stable, secure and accessible housing is a vital resource in old age, linked to life satisfaction, wellbeing and life choices (Hu, Reference Hu2013). This paper focuses on the housing circumstances and arrangements of older Malaysians who are childless and poor. Such older people are especially vulnerable in the Malaysian context because they lack the support of adult children to assist in care and financial transfers in a policy and service system environment where families are expected to be the main providers of such support. The responsibility of younger family members for the care of the elderly has been emphasised at a social, cultural and policy level. The government's role in providing social support is targeted to complement rather than to replace family provision (Hamid and Yahaya, Reference Hamid, Yahaya and Lee2008). Access to affordable and appropriate housing is a priority for remaining independent in the community. Poor and childless older people have few means to purchase services that would make up for services usually provided for many by adult children.

A number of studies have noted the link between housing-related issues and other life domains (Izuhara and Heywood, Reference Izuhara and Heywood2003; Feijten and Mulder, Reference Feijten and Mulder2005; Vanhoutte et al., Reference Vanhoutte, Wahrendorf and Nazroo2017). The ability to accumulate housing resources is influenced by a chain of events over the lifecourse. These include family life, employment, education, income and inheritances, partner relationships, health, location, and structural contexts including policy and service support systems, and social, cultural and political changes. Earlier advantages and disadvantages can be accumulated as well as diminished over time. This paper uses the lifecourse perspective to understand success or otherwise in the accumulation of such an asset and links individual and family histories with structural opportunities and impediments.

The paper is based on a larger project exploring the experiences of social support of older Malaysians who are childless and poor. It reports on the housing trajectories and transitions of this group and their implications for current and future wellbeing. It aims to discuss the current housing arrangements of childless and poor older people, and explore how lifecourse events intertwined to influence current housing arrangements for this group in old age. The implications of these findings for this group are then considered.

Fundamentals of the lifecourse perspective

The lifecourse perspective (Elder, Reference Elder1998, Reference Elder2000: 50–52; Elder and Johnson, cited in Marshall, Reference Marshall, Bengtson, Gans, Putney and Silverstein2009) proposes that an individual lifecourse results from a combination of circumstances and events which are influenced by many factors such as family background, education, marriage, employment and housing. It views individuals’ lives as embedded within the social, historical, cultural and policy contexts. These structural factors have the capacity to both influence, and be influenced by individual lives and decisions. The notion of lifecourse also emphasises the cumulative effects of earlier advantages and disadvantages to later life (Phillipson and Baars, Reference Phillipson, Baars, Bond, Peace, Dittmann-Kohli and Westerhof2007). Individuals are viewed as having the ability to shape their life by making decisions and choices based on their circumstances. Where individuals are living in the community generally, and with family specifically, their life is essentially intertwined with and affects each other. The lifecourse perspective addresses this relationship with the concept of linked-lives. This approach is useful in understanding how earlier lifecourse events shaped the current housing arrangements of childless and poor older people. In a recent study in Hong Kong, the lifecourse perspective is used to examine the interactions between individual lives with family, social and historical events, and at the same time acknowledges the capability of individuals to make decisions under a given set of opportunities and constraints (Kwok and Ku, Reference Kwok and Ku2016). Some previous studies (Dykstra and Hagestad, Reference Dykstra and Hagestad2007) also used the lifecourse perspective in understanding childlessness in old age generally. This paper, however, aims to look at the lifecourse influence on the current housing arrangements of childless and poor older people. It explores the link between childlessness, poverty, lifecourse and housing in a particular social and policy context.

Childlessness, poverty and housing in old age

There is no consensus or widely accepted definition of childlessness. Some researchers noted that childlessness in old age is not simply about not having children biologically, but also inclusive of those who outlived or were estranged from their adult children (DeOllos and Kapinus, Reference DeOllos and Kapinus2002; Dykstra and Wagner, Reference Dykstra and Wagner2007; Allen and Wiles, Reference Allen and Wiles2013). In some instances, childlessness included foster (Dykstra and Hagestad, Reference Dykstra and Hagestad2007), adopted (Koropeckyj-Cox et al., Reference Koropeckyj-Cox, Pienta and Brown2007), stepchildren (Zhang and Hayward, Reference Zhang and Hayward2001) and de facto Footnote 1 childlessness (Zimmer, Reference Zimmer1987; Schröder-Butterfill and Kreager, Reference Schröder-Butterfill and Kreager2005). In this paper, childlessness in old age describes older people who do not have support from adult children, regardless of how children are defined.

A concern noted in studies on childlessness is the perceived negative consequences for social support and wellbeing of being childless in old age. Adult children are generally seen as an important resource in older age, providing support and care (Masud et al., Reference Masud, Haron and Gikonyo2008). There are generally strong intergenerational transfers between parents and children in a family. The extent, nature and direction of these exchanges vary according to differences in welfare systems, as well as cultural values. For example, Khan (Reference Khan2014), in his study on intergenerational transfers across 24 countries, showed that older people in countries with limited access to formal support, such as in Asia, are more likely to receive financial transfers from their children as compared to other regions. Similarly, in Malaysia, children are expected to be the main providers of support and care for older people (Hamid and Yahaya, Reference Hamid, Yahaya and Lee2008). There is also a strong traditional value of filial piety among Asians that reinforces a reliance on family support to provide care for older people, particularly where the social security system is less developed (Zeng and Wang, Reference Zeng and Wang2014). The experiences of childlessness in old age may vary due to differences in context of each country. Childless older people who are poor, therefore, could be more vulnerable in the context of less-developed welfare systems and in a society with strong family values and expectations of family rather than where state-based income support and care prevail.

The relationships between housing arrangements and individuals’ wellbeing, life satisfaction and/or quality of life are well established. Some researchers found that home-ownership has a positive effect on life satisfaction (Rohe and Stegman, Reference Rohe and Stegman1994; Hu, Reference Hu2013). Individuals who are renting were more likely to feel insecure and vulnerable to housing as compared to home-owners (Zainal et al., Reference Zainal, Kaur, Ahmad and Mhd Khalili2012). The fear of losing the ability to house themselves can occur for individuals at any stage of life, however, it is likely to be a more distressing experience for older people, particularly the poor who have limited capacity to accumulate new resources. Older people tend to appreciate residential stability in this stage of life (Dunn, Reference Dunn2000), thus any changes towards their housing arrangements may cause anxiety due to life uncertainties. Insecurity and instability in housing can impact on wellbeing and quality of life.

Access to affordable, stable, secure and accessible housing in older age has been identified as a valuable resource and failure to accumulate financial resources over the lifecourse can make this difficult (Izuhara and Heywood, Reference Izuhara and Heywood2003). Wealthier childless older people have more options, and can afford to purchase support services, and/or are more likely to have access to support from their extended family members who are perhaps motivated by potential inheritance (Schröder-Butterfill, Reference Schröder-Butterfill, Kreager and Schröder-Butterfill2004).

Malaysian demographic, social and policy context

Housing and ageing take place in a social, cultural and policy context. Malaysia is a multi-racial society with a population of more than 28 million. The Malaysian population is comprised of three majorFootnote 2 ethnic groups with MalaysFootnote 3 and other natives (67.4%), Chinese (24.6%) and Indians (7.3%) (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2011). Older people, defined as aged 60 years and above, made up 8.4 per cent of Malaysians in 2010. Older people comprise 56.9 per cent Malays,Footnote 4 35.6 per cent Chinese and 6.4 per cent Indians. It is of interest to note the over-representation of Chinese in the older population relative to their proportion of the general population.

A mix of increased longevity and reduced fertility has fostered concerns about the provision of economic and social support for older people (Department of Social Welfare Malaysia, 2013). In response, the retirement age was increased to 60 years from 58 years in 2012. Researchers exploring social protection and security for older people (e.g. Hamid and Yahaya, Reference Hamid, Yahaya and Lee2008; Ong et al., Reference Ong, Philips, Hamid, Fu and Hughes2009) acknowledge that the older population in Malaysia is a heterogeneous group with differences in demographic, socio-economic, cultural and religious backgrounds. The knowledge of certain sub-groups within the older population, however, remains limited. One such group with limited visibility in national population surveys are older people who are poor and do not have the support of children in their old age.

Prior to 1995, issues related to older people were addressed in the broad context of welfare (Ong et al., Reference Ong, Philips, Hamid, Fu and Hughes2009). There was no specific policy for older people in Malaysia until 1995 (Department of Social Welfare Malaysia, 2013). Malaysia has no state-based universal aged pension. The main source of economic support in old age comes from the contributory retirement fund (the Employee Provident Fund (EPF)), the pension fund (for civil servants), personal savings (Goh et al., Reference Goh, Lai, Lau and Ahmad2013) and intergenerational transfers from adult children (Masud and Haron, Reference Masud and Haron2014).

The EPF, established in 1951, is compulsory for those who work in the formal employment sectors with established and registered companies. Informal employment (including those self-employed in small-scale operations) is less regulated. Many older people today were more involved in informal employment as a result of low levels of education excluding them from formal employment. Their schooling was limited because it was neither compulsory nor free or was interrupted by war and/or political instability prior to independence in 1957.

The EPF is not only important as retirement savings generally, but also serves as a means of saving to purchase a house. Contributors are allowed to withdraw from the EPF for housing purposes. The lack of EPF funds limits the possibility of using this funding for housing purposes. In 2012, Private Retirement Schemes were implemented potentially to safeguard a group of people involved in employment (i.e. self-employed, informal employment) who are not covered by the EPF. This initiative, however, has little impact on the current cohort of older people who have reached old age without sufficient retirement funds and/or individual savings. Those who lack children to provide financial support are thus in a vulnerable situation.

A public financial assistance scheme of MYR 300 per month (recently increased to MYR 350 per month) is provided by the state for poor older people who have no income and no family support, in order to sustain living in the community. This is a very basic payment when compared with the median income (MYR 864 per month) for workers with no formal education, according to the Salaries & Wages Survey Report 2014 (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2015). There is also financial assistance known as Baitulmal for the Malay community regulated by the Islamic Council. Baitulmal can also be received in the form of housing assistance. However, there is no provision in housing policy that is specifically directed to older people in the community, except for some emphasis on the facilities such as elderly-friendly housing areas. Besides the public low-cost housing programme which targeted poor families and squatters, the housing options for older people with low income are limited (Hamid and Chai, Reference Hamid and Chai2013). Poor older people who did not manage to secure public housing, or did not have the support of their social networks and/or could not afford private rental, may end up homeless. The government has taken measures to address this issue through Acts and Rules focusing on poor and homeless older persons since the 1980s (Hamid and Yahaya, Reference Hamid, Yahaya and Lee2008). There are public homes or shelters for older people who lack support in the community. This institutional care is seen as a last resort (Ong, Reference Ong2001). Older people generally prefer (Yahaya et al., Reference Yahaya, Siti Farra, Chai, Haron, Hamid, Sharifah Norazizan, Laily, Asnarulkhadi and Ma'rof2006) and are encouraged by the policy context to remain living in the community and be independent rather than living in residential care.

Research methodology

This paper aims to explore the link between lifecourse events and experiences, and the current housing arrangements of this group. A qualitative approach is appropriate for an exploratory study seeking to gain a rich understanding of the views and experiences of a particular group.

Sampling

The sample of interest is older people who are childless and poor living in the community. The data collection took place in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The urban poor in the capital city are likely to be particularly vulnerable due to the high cost of living in the area (Zainal et al., Reference Zainal, Kaur, Ahmad and Mhd Khalili2012). As a ‘hard-to-reach’ group, recruitment was through the sole welfare office of Kuala Lumpur, the key provider of welfare for poor older people. This strategy also ensured the use of a national standard of poverty to determine the eligibility of the sample. The Department of Social Welfare reported that, of 142,032 older people in Malaysia who received Older People's Financial Assistance in 2014, 40.7 per cent were Malays, 19.1 per cent were Chinese, 9.1 per cent were Indians and the rest were natives. Approximately 3.7 per cent or 4,452 older people of the total older population (118,788) in Kuala Lumpur in 2010 received the welfare financial assistance (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2011; Hamid and Chai, Reference Hamid and Chai2013) regulated by the department for the poor. However, genderFootnote 5 and marital status breakdowns were not readily available from the Department's annual report on recipients of various assistance including Older People's Financial Assistance. Specific reports on childlessness in old age are also lacking.

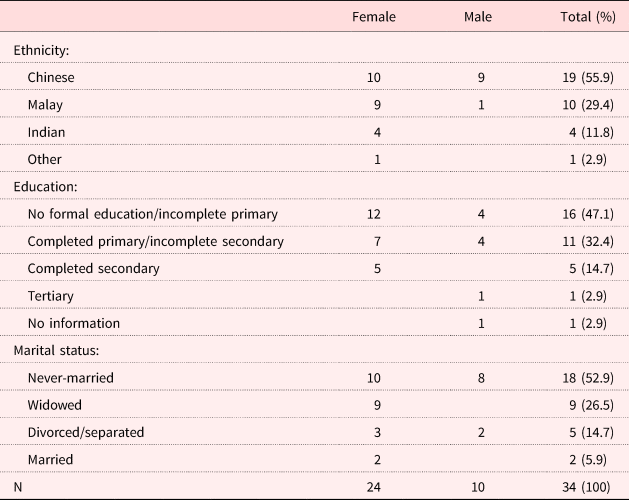

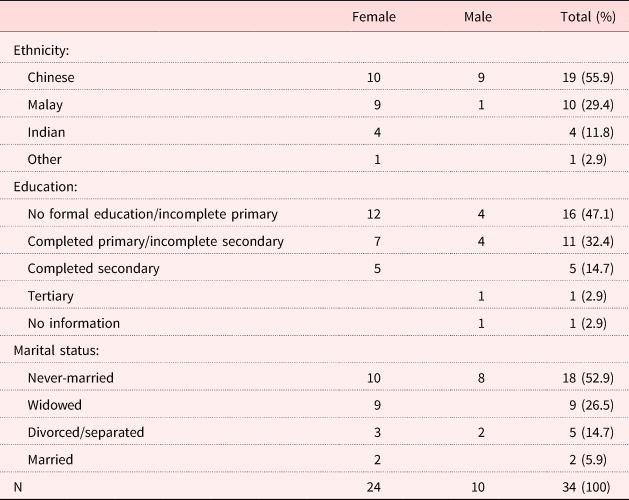

A purposive sample of older people who were childless and poor was recruited as participants from March to June 2014. The purposive sample sought to include variation in gender, ethnicity and marital status. As there were no data on childlessness in the departmental records, the target group was difficult to identify and quota sampling was not possible. Across a four-month period 34 participants were able to be recruited. The first author was positioned in the only welfare office in Kuala Lumpur and also accompanied an outreach team. She approached people with details of the study who welfare staff indicated might fit the sampling criteria. The sample description is in Table 1. Although attempts were made to obtain greater variation, most who agreed to be interviewed were women (70%), Chinese (56%) and never-married (53%). Although the sample contains this bias, it should be noted that most recipients of the assistance were women in Kuala LumpurFootnote 6 (see Note 5) and that the proportions of Chinese, Malay and Indian participants closely reflect the ethnic distributions among the older population in Kuala Lumpur.Footnote 7 Despite being fluent in Malay, Cantonese and English, the first author is a Malaysian Chinese and this may have impacted on the willingness of other groups to participate when direct contact was made. All participants were aged between 62 and 82 years, aligned with the national definition of an older person as aged 60 years and above. Most participants were the current recipients of the welfare financial assistance; some were having their applications updated or renewed which happens annually.

Table 1. Distribution of the sample by selected characteristics

Ethical considerations

The study was cleared by the human research ethics committee of the relevant university. Gatekeeper approval was obtained from the relevant government agencies and the welfare office. The role of the welfare office was to provide a private office for interviews and indicate who might be approached regarding participation. The welfare office played no role in providing additional information or oversight. Participants were reassured verbally and in consent forms that the research was based in a university, not attached to any agencies or the welfare office, and in no way could or would influence any dealings with the welfare office. Participation was on a voluntary basis and participants’ identity remains confidential to ensure that participants were able to share their stories willingly and openly. At the end of the interview, participants were provided with some money (MYR 60), enough to purchase groceries or several meals in recognition of their time and interest in the study.

Data collection

Life history interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide. Participants were asked about their life in younger years, family background and education; their transitions to adulthood in the areas of employment, relationships and marriage; and current arrangements including social support and how they managed. They were also asked to talk about their accumulation of assets including housing and the factors that influenced transitions and choices. Face-to-face interviews were carried out to allow participants to reflect on their life experiences of social support, including housing, as childless and poor older people. Participants were also able to convey and identify previous life events, and make their own interpretations of the events and decisions made throughout their lives (Muirhead et al., Reference Muirhead, Levine, Nicolau, Landry and Bedos2013).

Interviews were conducted by the first author in a private room in the welfare office or in a participant's house in one of the three languages, Malay, Chinese or English, as chosen by the participant. The data were translated and transcribed into English. During the process, the first author adopted the meaning-based translation as suggested by Esposito (Reference Esposito2001) and Larson (Reference Larson1998). That is, ‘the interpreter (researcher) conceptualised the meaning and, using vocabulary and grammatical structure appropriate for the target language, reconstructs the meaning of the statement’ (Larson, cited in Esposito Reference Esposito2001: 570). However, to ensure the accuracy of the data and transparency of the process, a sample of the transcriptions was sent to an experienced translator. The second and third authors also assessed and agreed that the meaning was consistent in both the transcripts from the first author and the experienced translator. Due to the illiteracy of most participants and/or concerns about the security of the documents, transcripts were not sent to participants for checking. The interviewer's understanding of participants’ story was checked during the interview or at the end by repeating some of the main events in their life.

The process of coding and thematic analysis was assisted by the qualitative software NVivo 10Footnote 8 (Wong, Reference Wong2008). The coding processes followed the six phases of thematic analysis identified by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Lifecourse concepts of individual and structural impacts on opportunities, linked-lives, transitions and cumulated disadvantage helped to organise the analysis. As both an insider and outsider culturally as a Malaysian Chinese to her participants, it is important to build a degree of closeness and trust so that they were more open in sharing information about their personal life. Her reactions and preconceptions and how they might influence the interviews and the subsequent analysis were discussed extensively with the research team. Rigour was enhanced by the contributions of the other authors in the team, for instance, on the initial coding of interview transcripts which were checked by the team members, each as an independent coder.

Results

The overarching theme in the interviews was maintaining independence in the context of poverty and older age. This included a desire to continue living in the community and remaining independent from family, if some family were still in contact. Access to housing was crucial to this independence and participants were prepared to reduce expenditure on food and other needs to protect this resource. The analysis in this paper reports on current housing arrangements and the factors that constrained or promoted access to this central resource.

Housing arrangements and its impacts on life in old age

Affordability, stability, security and accessibility are key issues in housing in later life among lower-income groups (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Bell, Tilse and Earl2007). These concepts were used to firstly consider the quality of current housing arrangements and then to link lifecourse events or experiences that had hindered or facilitated the accumulation of appropriate housing resources. Participants’ current housing arrangements represent a hierarchy which can be categorised into four types: home-owners, public renters, private renters and those who have an informal housing arrangement. No participant was currently homeless, although one woman had been homeless before being put in contact with the welfare office. This sampling limitation will be further considered later in the paper. This section discusses the advantages and disadvantages of these housing arrangements based on key issues of affordability, stability, security and accessibility of housing, and its impact on life.

Hierarchical structure of housing

Most childless and poor older people in this research have been struggling to get their housing needs met over their lifecourse. Housing arrangements were likely to remain unchanged or worsen as they age, due to limited resources over time. Home-owners (N = 7) were participants who managed to accumulate housing resources over their lifecourse and owned a house at the point of interview. These were a minority in the sample. Public renters (N = 9), on the other hand, were participants who were renting and living in public housing provided by the government, at the affordable rate of MYR 124 per month. Private renters (N = 8) were participants who were renting in the private market, while participants who have an informal housing arrangement (N = 10) were those who were staying informally within their social networks (i.e. family and friends) without the need to pay a monetary rental.

Home-owners are the most advantaged as they enjoyed the stability, affordability and security of their own house. In contrast, those who had informal housing arrangements were the most disadvantaged. Although informal housing is affordable, this housing arrangement is highly dependent on participants’ relationships with the provider, hence, it does not necessarily provide stability and security of housing:

if they [nephews/nieces] want to sell the house, I will have no place to stay … Now that they are ‘accepting’ me, so I will just stay there … I would not be so pathetic if my sisters were around. (P016, never-married Chinese woman aged 76)

This participant is at risk of being evicted because of the lack of relationship with her nephews/nieces as compared to her sisters. However, most were grateful with the housing assistance provided by their social networks. They felt the need to reciprocate by doing household chores to ‘repay’ the provider:

I am helping a bit (without asking to do so) … I would keep the clothes away when it rains … I just help out. I still need to help others in the house if I could run and walk, as I am staying with them. (P023, never-married Chinese woman aged 78)

Despite being in a housing arrangement that does not offer stability and security, those who benefited from informal housing arrangements reported on the importance of these networks and the assistance provided.

Although some had willingly accepted help from their networks, others were reluctant to receive such housing assistance. Despite the availability of housing provided by their family networks for some, they chose to be independent and remained in the private rental market. Interestingly, this did not reflect that they had sufficient resources to pay for rent in the private rental market. Instead, they did not want to rely on others for support or feel obligated with the responsibilities to reciprocate, if they were to stay with their family members. It was a choice made considering their position and relationship with their family members:

If I cannot pay the rent, I have to move back to my [mother's] house and I wouldn't know what will happen. I am dreading the day to go back as I don't want to go back. It will be a hell for me. Three of them [siblings] also couldn't get along as they fight against each other. I have to provide them food. (P019, never-married Chinese woman aged 70)

Staying with the family members could probably solve housing issues, but it also promotes conflict and potentially made emotional wellbeing difficult to achieve.

Informal housing arrangements are highly dependent on social networks; private rental housing is more accessible to older people regardless of social networks. However, this arrangement did not offer affordability, security and stability. Not being able to afford to pay rent at any point in time could put the tenant at risk of losing a place to stay. Most participants who were renters in the private market were struggling, as they had limited financial resources. Due to depleting resources, half of the participants who were renting a place either in the public or private sector reported working in old age. They were primarily involved in odd jobs and some collected recyclable items for some cash. A participant described the importance of having a job to manage her rental:

I ended my MYR 800 job last week … Then, I am paying MYR 300 for my rental … Now, my worry is the rental, the food … I can survive with water. (P019, never-married Chinese woman aged 70)

Generally, participants who did not have affordable, stable and secure housing sought to meet this important need first before the other needs (i.e. food). Some private renters described a very limited diet of rice and water.

In this context, the need to pay rent on a low income had a substantial impact on their quality of life in old age. The impact of housing arrangements among childless and poor older people, however, is not simply about taking care of rent, but also about the housing condition that is linked to the arrangement. Due to the limited financial capacity to rent, most private renters could only afford to rent a room instead of a house. For some, this meant no cooking facilities and hence a higher cost of living:

I buy the dishes from outside. This is because I only have a room, I don't have a place to cook. (P025, never-married Malay woman aged 67)

The struggle to pay rent was ever present for most private renters, and this brought distress and anxiety. Most participants in this research had led difficult lives and did not expect old age to be any better. They hoped to have sufficient resources to last their days and focused on living in the moment. Their acceptance of their life situation, however, does not spare them from feeling insecure about their future. Without children to provide care when their health fails or they could no longer afford to pay rent, public residential homes were seen as the last resort. Although participants were aware of the availability of these homes, the possibility of entering homes was primarily driven by the need for care more than housing:

So I thought it would be better if I ask for the [financial] assistance and support myself … The officer was suggesting why not I stay at the public old folks home. I rejected it … I can [still] walk around and all, I don't think I can stay in there [old homes], as I will go crazy. (P025, never-married Malay woman aged 67)

For this woman, the residential homes appear to be an option for housing and care later in life, but it is not an earlier life transition of choice. The reluctance is mainly due to a perception that the homes are for the frail, and that their resource for housing in the community has not been exhausted yet.

The impact of structural and policy factors

Participants who lived in public housing were better off compared to those in the private rental markets and informal housing arrangements. This housing provides affordability, security and stability. However, it was not accessible to all as the supply is limited and eligibility criteria exclude some groups. Never-married and/or childless individuals had experienced exclusion from this housing option. This will be further discussed in the later section on opportunities and constraints.

A few participants who were living in public housing had perceived that they were achieving a better life in old age as compared to their early years. Coupled with the welfare financial assistance in old age, public housing had made previously hard lives somewhat easier. For example, a Malay woman in the public housing reported:

My life is better. I have milk, I have oat, because I have welfare money. (P018, separated, Malay woman aged 67)

Another Malay woman (widow) mentioned that her life is getting easier in old age which can be attributed to her current public housing:

From the beginning to the middle it has been difficult, and at the end, it is easier. Now, it is a little bit easier. It became easier in old age. Easier in term of the food and living place. (P014, widowed, Malay woman aged 78)

Participants who had more positive outlook of life in old age were those who enjoyed more affordable and stable housing as a result of being home-owners or public renters in old age. Access to affordable and stable housing resources had contributed to their independence and hence, the perception of better life in old age. Nevertheless, despite achieving a better life in old age, they were no different from the majority who were worrying about their future life, with maintaining their health and independence, being their main concerns. Having no children and with limited resources in old age, self-sufficiency is essential to avoid the possibility of being institutionalised.

Given that housing arrangements in old age differed among participants, how they came to have these housing arrangements in old age is explored in the next section.

Accumulating housing resources for old age

Lifecourse experiences influence housing trajectories (Izuhara and Heywood, Reference Izuhara and Heywood2003). The lifecourse perspective emphasises the sequences of different life events in an individual life, and the cumulative effects of the previous events on to the subsequent one. As individual life circumstances vary, some have more advantages than others. In this context, the ability to make choices may not be available to all individuals due to constraints such as a lack of resources or, in another circumstance, a structural constraint. The effect of such constraints or opportunities can be lasting as they tend to accumulate over time. Broadly, in this research, this group of older people had experienced more disadvantages than advantages over the course of their life. Most were from poor families and this had affected their subsequent trajectories in education, marriage, employment and, therefore, housing. In other cases, the opportunities and constraints in decision making related to housing are influenced by a combination of individual life circumstances and external factors, such as social, cultural and policy factors. For instance, a few participants were from relatively well-to-do families with higher education as compared to others, however, they ended up in a similar situation on housing and did not necessarily own a house in older age. This will be discussed throughout this section.

Earlier cumulative effects

Family poverty restricted access to education and this then affected employability. Most participants never had the opportunity to be educated when they were younger. Many older people were not well educated as education was an expense to the family and not accessible to some groups. The current cohort of older people in Malaysia was of school-going age in the 1940s and 1950s when the education system in the country was not well established. They were born in the pre-independence era when the country was unstable in many respects. For instance, one participant who dropped out of school reported how the Japanese and British occupations in 1940s and 1950s had affected her education choices and trajectories. Those living in the villages or more rural areas were also highly affected. These were primarily Malays, where schools were not available in their locations:

The English school was available, but it was for those who were rich, for those rich officers. We were the poorer one, we couldn't get into the expensive one. We can go into the Malay school only [in which there was no secondary Malay school around yet]. (P032, divorced, Malay woman aged 67)

Some did not have an option to be educated and started working at a very young age, as education was not made compulsory until 2003 (Tie, Reference Tie2011) and family poverty made work a necessity. With limited education, most participants were restricted to informal employment. This type of employment brought about disadvantages in accumulation of resources. The contribution to the retirement fund (EPF) is not compulsory for informal workers. This was similarly experienced by both men and women, although the nature of their jobs differed. Men tended to be involved in work that required physical work and/or some skill such as a tailor, an electrician or a carpenter that did not require high education; while women worked as domestic workers or cleaners where they turned their traditional jobs into income-generating jobs. Some of these men and women had lived with their employers which meant lower wages at that time, and no housing when they could no longer work. Due to the nature of work in informal employment, there was no demand for EPF and it was uncommon in the industry:

No, we don't have it in this industry. We don't have things like EPF. (P011, never-married Chinese man aged 71)

No, I don't have EPF, very little. No. We don't understand this, we don't know about it … If I know I would have asked the boss. Why didn't we have the EPF. (P013, never-married Chinese man aged 77)

As a result, the disadvantage of a low level of education became more prominent with the lack of knowledge and poor employment without EPF resulting in few assets and/or savings accumulated for older age.

Familial relationships

Family structure and background had a role in influencing individual housing careers. A small number of participants had inherited a house from their late parents and became home-owners living in the city. The inheritance, however, often comes with a trade-off. For example, a never-married woman became a home-owner after the passing of her mother, for whom she had cared for most of her life. Partly because of her caring responsibility, she did not get married. In old age, she was living alone without her own family. Others with an inheritance reported coming from villages and migrating to the city earlier in their lives, mainly to seek employment. These participants who were primarily Malay had an option to go back to their villages where the family village house was available. Although, for some, they would have to share the house with the existing family members in the village, the option to be provided with housing remained open for them. Their relationships with the family members and community in the village, however, may not be good, and this affected their choices and decisions:

I didn't feel like staying in the village. Moreover, the neighbour would have a lot to say, that my brother need to support me and all, although I don't ask for his support. (P025, never-married Malay woman aged 67)

For most, the village house was not an option at all and they could not take advantage of the family resources provided through inheritance.

A house could also be inherited from a partner/spouse. One Chinese widow explained that she and her late husband managed to purchase a house with their work income earlier in their life, and in older age, she enjoyed more stability and security in relation to housing when compared to others. Their ability to accumulate resources through employment and acquire a housing resource was an advantage. A small number of participants also reported being able to purchase a house from their accumulated financial resources. Some better-educated participants were from this group. However, not all had managed to keep their house into older age. A participant who had a relatively well-to-do family earlier in her life and managed to complete her secondary education described:

at one time I got a house … But somehow, I was struggling between jobs … I needed cash to survive … I had to sell my house. So in the end, I sold my house for MYR 75,000. (P019, never-married woman aged 70)

This also highlights the impact of individual choice and decision making.

Individual decisions and situational disadvantages

Despite career instability and involvement in various types of employment, some had had some retirement funds and savings accumulated throughout their working years, but these were a modest amount:

I thought of buying a house, but the private ones were too expensive … I could afford to buy as I have MYR 80,000 [at that time] but I need it for my expenses and if I buy a house, it wouldn't be enough. (P025, never-married Malay woman aged 67)

However, she had made an active decision not to buy a house despite her ability to do so at that time, for fear of the living costs and income uncertainty. In old age, she is renting in the private market. This suggests that making a decision about housing is related to an individual's decision on other aspects of life. In another instance, a tertiary-educated man with good employment who once had his own house sold it earlier in his life to make up for his loss in an investment, and was now depending on a non-governmental organisation for housing assistance. This highlights that although most described a lifetime of poverty and limited resources, for some financial circumstances changed as a result of life events.

Poor health status had also affected one participant who decided to abandon the idea of purchasing a house:

I had saved some money but then I spent a lot seeing the doctors … I was afraid of the future … Therefore, I had abandoned the idea of buying a house. (P012, never-married Chinese man aged 65)

Purchasing a house, however, was not a priority for some, especially among the never-married men:

no one was talking about buying house at that time. All friends gathered are to eat and drink together … So I didn't think about buying a house. I feel regret for not getting a house. (P026, never-married Chinese man aged 70)

Most had concentrated on remaining in employment, a choice made based on their situations at that point in time, and missed the opportunities to become home-owners. For a few never-married men, accommodation had also been provided with employment and, hence, it may not have been necessary to purchase a house earlier in their life. However, once their services were not needed, they were left with no place in old age and with limited savings due to the provision of accommodation in the employment with lower pay:

The salary was low last time … The food and accommodation were provided, how much [salary] could they give? (P013, never-married Chinese man aged 77)

Men in this study were more likely to move from one place to another in search of employment, particularly if they were never-married and, hence, convenient housing such as private housing was preferable for its flexibility.

Structural and policy impacts: opportunity and constraint

Housing policy was an important structural factor linked to participants’ housing arrangements in older age. Public housing is built to cater for the housing of those who are poor under different programmes and schemes. The New Economic Policy, introduced in 1970, aimed to eradicate poverty and restructure society. Rural Malays were encouraged to migrate to the city. As a result, squatter settlements increased (Sufian and Mohamad, Reference Sufian and Mohamad2009). Later, in the 2000s, under the People's Housing Program, the relocation of squatters in the urban areas to new housing was expedited to provide the poor with proper housing facilities. Some participants from those resettlements benefited from the relocation and managed to obtain a unit of public housing. Some, however, did not make a smooth transition from being a squatter to living in public housing. They reported that they were ‘dropped off’ in the process for various reasons due to its affordability, the complexity of the procedure and were disadvantaged by their marital status or family composition. Generally, priority for provision of a unit of public housing was given to applicants who were married, divorced or widowed (Sufian and Mohamad, Reference Sufian and Mohamad2009) or with older parents (DaVanzo and Chan, Reference DaVanzo and Chan1994). In the current research, five out of six women were widowed or had separated/divorced and were living alone in the public housing, while another married woman lived with her husband. Current or previous marital status was an advantage for these women to secure a unit of public housing.

On the other hand, a few never-married participants in the research had reported failure in obtaining public housing due to their marital and parental status:

I wanted to get a house, the house built by the government. But, without a family I failed to apply. (P001, never-married Chinese man aged 72)

In another instance, a Malay woman explained:

The house that the government built was for those who have families, however, I am single and younger, I couldn't get it. Until I am older and senior, I still don't get it. (P025, never-married Malay woman aged 67)

A larger number of participants who were or had been married were living in public housing, as opposed to those who were never-married who were mainly in the private rental market. There has been a failure of policy to notice the diversity of individuals who may need support when catering for the housing needs for the people (Izuhara and Heywood, Reference Izuhara and Heywood2003).

Participants who could not afford to become a home-owner and were not eligible for public housing went into and remained in the private rental market – for most, as soon as they left the parental house:

After he [elder brother] had children, I moved out myself and started renting room … I took care of myself since then. (P011, never-married Chinese man aged 71)

Employment income was one of the main sources of income to support private rental. Some participants were struggling to remain in the private rental market in old age when health status limited employability.

Social networks and linked-lives

Linkages to community organisations benefited certain groups of older people. Some older Malays benefited from the assistance provided by the Islamic Council to assist the poor regardless of age:

Baitulmal is paying [the rent] for us. But I need to pay for the water and electricity bills. Electricity bill around MYR 40 per month, and the water bill is MYR 25 per month. That's all I have to pay. (P035, currently married Malay woman, age 70)

Baitulmal was taking care of her rent and she was able to live independently with welfare financial assistance.

Not all private renters had access to community support in old age that allowed them to continue staying in the private rental market when they could no longer afford the rent. Some participants had also moved into informal housing arrangements which involved some degree of reciprocity in tasks and/or responsibilities:

Since I have stayed there for quite some times, and I am alone there, the owner was asking me to clean the house and look after her two kids. As I do that, I don't have to pay for the rent and I save that [money]. (P027, widowed Chinese woman aged 81)

Having no family of their own or children means that their friends became their main supportive community and networks. In older age, some were being offered accommodation by their friends with no or minimum fees (rents). A participant described his experience with his housing arrangement:

I don't have to pay for the food [the friend is buying him food], as for the rent, he charges me in low rent, because I help him to do some cleaning and other friends are helping out [too]. (P012, never-married Chinese man aged 65)

These participants were provided housing by their networks of friends and family. However, there was a gender difference in relation to the network that provides housing assistance. Never-married women had a better relationship with their family members as compared to men whose friends were their main network – networks which they could contact mainly for non-financial support including housing. Unlike never-married men, women were more likely to stay or work closer to their family or, for some, return to their parental home in older age despite leaving for work in their younger years.

The provision of housing assistance by the social networks can be obtained not only from the existing networks but also from newly developed networks of friends. A small number of participants had managed to get their housing needs met through newly developed networks:

I know him [friend] there [church] … He is my friend. He said, ‘is okay, you can stay with me, since I have two rooms, is okay, you don't need to pay, only pay a little for the utilities will do’. (P006, widowed Indian woman aged 63)

Individuals’ ability to react and build a close relationship with others in time of need opens up an opportunity to be provided with assistance. One never-married man in the study had reported having approached a non-governmental organisation in older age as a volunteer with the hope of being provided with accommodation if needed later. Some participants, therefore, make an active decision to be assisted and willingly accepted the assistance in times of need. However, these participants tended to highlight the instability and insecurity of this type of arrangement where there is a risk of eviction at any time. If there is a change in the relationship between the participant and the provider (i.e. families or friends, or existing or newly developed networks), they may not be able to continue with the informal housing arrangement. The need and effort to manage the relationships with the provider became the determinant of continuous housing provision:

They tell me that I cannot rent it [one of the two rooms] out but instead they want to rent out both of the rooms … I asked them, where am I going to stay then? on the street?! …They said, I am old … it sounded like wanting me to die. I was so angry. (P016, never-married Chinese woman aged 76)

This was the group most at risk of being homeless and/or institutionalised. In short, generally there are fewer opportunities and greater constraints in accumulating housing resources over time. The cumulative effects from various aspects worsened for many as they grew older.

Conclusion and implications

Individual, cultural and structural factors intertwine over an individual's lifespan to shape housing arrangements in older age. Lack of success in securing secure housing earlier in life, combined with poverty and childlessness in older age, limit opportunities for affordable and appropriate housing. As Malaysia gained her independence during their childhood or early adulthood, this group of older people experienced various social and policy changes. These changes partly contributed to shaping the history of their family, and their education and employment trajectories, which mostly negatively impacted on their ability to accumulate housing resources. Never marrying was a disadvantage in public housing allocation and, for most, purchasing a home was not affordable. Limited conclusions, however, can be drawn based on differences between gender and cultural groups. Differences in housing arrangements between genders may be a result of the small sample size of men who were predominantly never-married Chinese. Thus, difference based on gender must be interpreted with caution. It is also not possible to explore the impact of cultural differences. Rather, the different housing outcomes for these participants could be attributed to differences in personal and social history and background (i.e. the availability of village houses for some Malays or the lack of schooling for village Malays), which impacted on access to housing resources and consequently their housing arrangements in older age.

Inequality in housing in old age was created in the process of accumulation of housing resources over the lifecourse. This has been reflected in the hierarchical structure of housing arrangements associated with advantages/disadvantages based on affordability, stability, security and accessibility of housing. Some may enjoy more stable and secure housing, while others struggle to have appropriate housing in old age. Some had managed to own a house earlier in life, but lost it over time due to life circumstances and individual decisions. By and large, there is an increased tendency for them to move downward in the hierarchy, given that they do not have the capacity to move upward due to poverty and low income in older age. Despite the struggles that they faced, such as poor health, inability to work and reduced income, they managed to continue living in the community. Maintaining independence was a strong value and housing was central to this. They did not see entering an institution as an option while they could still manage, though a number feared this may be the eventual outcome. They are survivors of a range of challenges and seek to remain in control of their lives despite few resources.

Social and policy expectations of assistance from family providing for older people were not met for this group of childless and poor. In fact, when there was some extended family, this group of older people did not want to ask for assistance from family members for various reasons, mainly due to pride and poor relationships with the members. Housing assistance may be available for some, but the acceptability of the assistance was an issue for them. Rather, this group of older people tends to rely on and is more hopeful for assistance from the government, the non-government service system and the non-family network. Therefore, it is important to recognise the role of welfare assistance in helping this group to survive in the community. Furthermore, non-institutionalised and affordable housing assistance in the community needs to be developed further to address the housing needs of this group of older people who are able to manage living in the community. Childlessness on its own is not the cause of housing problems in old age. However, for those who are childless and poor in old age, their disadvantage in a Malaysian context is likely to be increased because of the lack of non-familial resources to provide support for their housing needs. Public housing policies need to consider how better to support this vulnerable group.

Research on childlessness in old age is limited in Asian countries, particularly in Malaysia. This qualitative study focused on a particular group of older people living in an urban area and in receipt of government welfare payments. The advantages of this exploratory study are that it has a diverse sample, interviews were conducted in three languages, and in-depth understanding of the vulnerabilities and strengths of this group of older people were gained. Sampling limitations, however, need to be acknowledged. Although some were precariously housed and living a subsistence life, all participants were in touch with the income support providers (the welfare office) and living in the community in Kuala Lumpur. Further studies should include an exploration of the social support and lifecourse events of childless older people who are homeless or living in residential institutions, and/or rural areas. Larger studies could then include greater variation in gender, ethnicity and marital status, although the difficulties of recruiting such a hard-to-reach group are recognised. The current study was not able to include homeless participants because of constraints in terms of time and resources in accessing this group and ethical concerns about interviewing people in crisis about their lifecourse. The study provides an in-depth exploration of childless and poor older Malaysians receiving income support. Studies of homeless older people could potentially provide different perspectives in relation to housing and childlessness in old age in Malaysia and in Asia.

Recent initiatives, such as the availability of retirement funds for workers in informal employment to promote savings for old age, and development in housing policy to provide more affordable housing to its people, may be more beneficial to younger generations, the new cohort of older people. It would also be of interest to study the effect of these initiatives on the housing arrangements of a different group of older people in the future. It would be useful for the national census to collect more detailed data at individual level, including data on fertility and childlessness, so that this group can become more visible in policy agendas and trajectories, and change can be tracked over time. The Malaysian population aged 60 and above is projected to reach 15 per cent in 2030. Approaching the benchmark to be classified as an ageing nation (Samad and Mansor, Reference Samad and Mansor2017) suggests the value of reviewing the reliance on family support in current policy and a greater understanding of the diversity of the ageing population and the impact of lifecourse events and trajectories on current wellbeing.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff, resource persons and participants of the ‘Writing Workshop on Population Ageing Research in ASEAN’, organised by the Institute for Population and Social Research, Mahidol University, Thailand, for their comments on an earlier draft. Also the authors thank the University of Malaya Population Studies Unit for a small amount of funding for the preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

All authors participated in the design of the study. YMN completed the data collection and analysis under the supervision of the other two authors. All authors collaborated in the preparation of the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by a scholarship provided by the Ministry of Education Malaysia and the University of Malaya, and University of Queensland funding available to support PhD research. The funding had no influence on the research processes.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval for the research was granted by the University of Queensland, Australia (2013001597).