Introduction

Population ageing is a global phenomenon, and older adults (⩾50 years) make up a substantial and growing proportion of the population. In Europe, 40 per cent of the population are aged 50 and older (Eurostat, 2018), and in the United Kingdom it is 35.4 per cent (self-calculated using data from Office for National Statistics, 2017), and these figures are projected to increase over the coming years (Office for National Statistics, 2018b). Although people are living longer, the number of disability-adjusted life years is increasing (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Vos, Lozano, Naghavi, Flaxman and Michaud2012) and quality of life is not guaranteed (Beard et al., Reference Beard, Officer, de Carvalho, Sadana, Pot, Michel, Lloyd-Sherlock, Epping-Jordan, Peeters, Mahanani, Thiyagarajan and Chatterji2016). In addition, older adults are at greater risk of social isolation (Iliffe et al., Reference Iliffe, Kharicha, Harari, Swift, Gillmann and Stuck2007) and feelings of loneliness (Shankar et al., Reference Shankar, McMunn, Banks and Steptoe2011). The reasons for this are complex and multifactorial but include widowhood, having no (surviving) children, living alone, deteriorating mental or physical health, retirement, relocation and bereavement – which are commonly experienced in later life (Peplau, Reference Peplau, Sarason and Sarason1985; Grenade and Boldy, Reference Grenade and Boldy2008; Cotten et al., Reference Cotten, Anderson and McCullough2013; Courtin and Knapp, Reference Courtin and Knapp2017; Age UK, 2018a). Understanding the factors associated with social isolation and loneliness in later life is important for identifying those at greatest risk and informing targeted interventions.

Social isolation refers to the objective status of a person's social relationships including network size, diversity and frequency of contact, whereas loneliness refers to the subjective psychological experience of the gap between a person's desired and actual levels of social contact (Peplau and Perlman, Reference Peplau, Perlman, Peplau and Perlman1982; Perlman and Peplau, Reference Perlman, Peplau, Peplau and Goldston1984; Peplau, Reference Peplau, Sarason and Sarason1985; Hawkley and Cacioppo, Reference Hawkley and Cacioppo2007; Cacioppo et al., Reference Cacioppo, Hawkley, Norman and Berntson2011; Shankar et al., Reference Shankar, McMunn, Banks and Steptoe2011; Steptoe et al., Reference Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos and Wardle2013b; Age UK, 2018b; Kobayashi and Steptoe, Reference Kobayashi and Steptoe2018). Although the two constructs have been shown to be positively correlated (Cornwell and Waite, Reference Cornwell and Waite2009a, Shankar et al., Reference Shankar, McMunn, Banks and Steptoe2011, Steptoe et al., Reference Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos and Wardle2013b; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Kaye, Jacobs, Quinones, Dodge, Arnold and Thielke2016a), persons who are socially isolated may not experience loneliness whilst loneliness may occur without social isolation (Perlman and Peplau, Reference Perlman, Peplau, Peplau and Goldston1984; Peplau, Reference Peplau, Sarason and Sarason1985; de Jong Gierveld and Havens, Reference de Jong Gierveld and Havens2004; Hawkley and Cacioppo, Reference Hawkley and Cacioppo2007, Reference Hawkley and Cacioppo2010; Cornwell and Waite, Reference Cornwell and Waite2009b; Coyle and Dugan, Reference Coyle and Dugan2012; Beneito-Montagut et al., Reference Beneito-Montagut, Cassián-Yde and Begueria2018; Kobayashi and Steptoe, Reference Kobayashi and Steptoe2018). Prevalence estimates of loneliness among older adults (60–80 years) in Europe range from 8.1 to 46.8 per cent (Hansen and Slagsvold, Reference Hansen and Slagsvold2016). It is estimated that up to 30.0 per cent of older adults (⩾50 years) in Europe are socially isolated (Cantarero-Prieto et al., Reference Cantarero-Prieto, Pascual-Sáez and Blázquez-Fernández2018).

Social isolation and loneliness are important issues because they are reciprocally related to health and wellbeing; that is, they are both a risk factor for and a consequence of poor health (Hawkley, Reference Hawkley, Gellman and Turner2017). For instance, a scoping review found both social isolation and loneliness can detrimentally affect the physical and mental health of older adults (Courtin and Knapp, Reference Courtin and Knapp2017). However, physical and mental health problems can lead also to increased risk of social isolation and/or loneliness (Fokkema and Knipscheer, Reference Fokkema and Knipscheer2007).

The health risks associated with social isolation and loneliness are many and varied, and may also be due to having a negative effect on health behaviours (Lauder et al., Reference Lauder, Mummery, Jones and Caperchione2006). Loneliness is associated with increased risk of premature all-cause mortality in older adults (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Hawkley, Waite and Cacioppo2012; Perissinotto et al., Reference Perissinotto, Stijacic Cenzer and Covinsky2012; Rico-Uribe et al., Reference Rico-Uribe, Caballero, Martín-María, Cabello, Ayuso-Mateos and Miret2018). Compared with never lonely older adults, those reporting often feeling lonely had a 130 per cent increased risk of cardiovascular disease risk and 22 per cent increased risk of ischaemic heart disease, even when controlling for age and sex (Patterson and Veenstra, Reference Patterson and Veenstra2010). Loneliness is also an independent risk factor for cognitive decline in older adults – for instance poorer cognitive performance, hastened cognitive decline, poorer executive functioning, slower processing speed and poorer memory (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Krueger, Arnold, Schneider, Kelly, Barnes, Tang and Bennett2007; Cacioppo and Hawkley, Reference Cacioppo and Hawkley2009; Boss et al., Reference Boss, Kang and Branson2015) – and is associated with 17 per cent higher odds of having a mental health condition in older adults (⩾50 years) (Coyle and Dugan, Reference Coyle and Dugan2012). Loneliness has been shown to be a risk factor for sedentariness and lower likelihood of engaging in physical activity, and increased likelihood of discontinuing physical activity (Hawkley et al., Reference Hawkley, Thisted and Cacioppo2009; Netz et al., Reference Netz, Goldsmith, Shimony, Arnon and Zeev2013; Hawkley and Kocherginsky, Reference Hawkley and Kocherginsky2017), and is also a risk factor for obesity, smoking and alcohol abuse (Hawkley and Kocherginsky, Reference Hawkley and Kocherginsky2017).

Social isolation is a predictor of mortality, independent of experiencing loneliness (Steptoe et al., Reference Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos and Wardle2013b). Social isolation has been independently associated with cardiovascular disease risk in older adults (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Hamer and Steptoe2009; Leigh-Hunt et al., Reference Leigh-Hunt, Bagguley, Bash, Turner, Turnbull, Valtorta and Caan2017) and is associated with increases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (Shankar et al., Reference Shankar, McMunn, Banks and Steptoe2011). People who are socially isolated are also less likely to engage consistently in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity at least once a week, and are more likely to be overweight or obese and smoke (Kobayashi and Steptoe, Reference Kobayashi and Steptoe2018).

One possible means of reducing social isolation and loneliness in old age is the use of modern technology, in particular the internet. Geographical distance to friends or family, mobility issues and time-consuming roles (e.g. care-giver) may impair older adults’ ability to engage socially, leaving them vulnerable to social isolation and feelings of loneliness (Leist, Reference Leist2013). However, using the internet may help foster social support, keeping in contact, development of social networks and improve self-confidence among older adults (Chen and Schulz, Reference Chen and Schulz2016). Using technology provides a low-cost and accessible means for communication that has the potential to reduce loneliness and social isolation in older adults (Chipps and Jarvis, Reference Chipps and Jarvis2016).

A systematic review showed technologies – such as social networking sites, general information communication technology (ICT), video games, chat rooms, 3D virtual environments – can be useful for reducing social isolation in older adults (⩾50 years) (Khosravi et al., Reference Khosravi, Rezvani and Wiewiora2016). Another systematic review of 25 studies showed that the use of ICT– such as Skype, Windows Live Messenger and telephone – increased social support, social connectedness and reduced social isolation among the elderly (age range 66–83 years), although the effects rarely lasted more than six months post-intervention, and even with adequate training some ICT interventions were not suitable for every older adult (Chen and Schulz, Reference Chen and Schulz2016). Many of the included interventions were only tested at one time-point, usually short term, and used a relatively small number of participants, thus the authors suggest a need for more well-designed studies (Chen and Schulz, Reference Chen and Schulz2016).

In a cross-sectional study of 11,000 older adults (⩾65 years) living in Europe, loneliness was reported less frequently by those who used the internet daily or sometimes compared with never users, and social isolation was less common among those who used the internet every day and sometimes compared with never users (Lelkes, Reference Lelkes2013). Despite indications that interventions using technology, particularly the internet, can reduce social isolation and loneliness, there is limited up-to-date information investigating associations between older adults’ current internet/email use in relation to their social isolation and loneliness.

Therefore, the present study used data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) to explore (a) the prevalence of internet/email use in older adults, particularly devices used and online activities engaged in; and (b) the associations between frequency of internet/email use with social isolation and loneliness. It was hypothesised that older adults who more frequently engage with the internet/email would be less likely to be socially isolated or to report feeling lonely, and that associations would be stronger for those who used technology most frequently.

Methods

Population

ELSA is a longitudinal survey of a representative cohort of adults aged ⩾50 years old living in England. The study began in 2002, with data collected via computer-assisted personal interviews and self-completion questionnaires in biennial waves (Steptoe et al., Reference Steptoe, Breeze, Banks and Nazroo2013a). To ensure the most current technology usage possible in a rapidly changing industry, cross-sectional data from the most recent wave, Wave 8 (collected 2016/2017), were used. Moreover, longitudinal analysis was considered not feasible due to attrition reducing the sample size within individual categories of internet/email use even further, leading to problems with statistical power. Complete data on all variables of interest were available for 4,492 of the total sample of 8,445 participants. Ethical approval was obtained from the London Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee and all participants provided full informed consent.

Measures

Outcome variables: social isolation and loneliness

Social isolation was computed using a five-item index as used in previous literature (Shankar et al., Reference Shankar, McMunn, Banks and Steptoe2011; Steptoe et al., Reference Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos and Wardle2013b; Kobayashi and Steptoe, Reference Kobayashi and Steptoe2018; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Firth, Firth, Veronese, Gorely, Grabovac, Yang and Smith2019a). One point was assigned to each of the following: if they reported having less than monthly contact (including face-to-face contact, telephone and written/email/text messaging contact) with children, other family members and friends, if they did not belong to a social organisation or club, and if they lived alone. Scores ranged from 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of social isolation. As in previous studies, scores were dichotomised at ⩾2 versus <2 points to indicate high versus low levels of social isolation (Steptoe et al., Reference Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos and Wardle2013b; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Firth, Firth, Veronese, Gorely, Grabovac, Yang and Smith2019a).

Loneliness was self-reported using a three-item short form of the Revised University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale (Russell, Reference Russell1996). Questions included: ‘How often to you feel you lack companionship?’, ‘How often do you feel left out?’ and ‘How often do you feel isolated from others?’. Response options were ‘hardly ever or never’ = 1, ‘some of the time’ = 2 or ‘often’ = 3. Total scores ranged from 3 to 9, with higher scores indicating greater loneliness. As in previous papers, these were dichotomised at ⩾6 versus <6 to indicate high versus low loneliness (Steptoe et al., Reference Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos and Wardle2013b; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Yang, Veronese, Gorely, Grabovac, Johnstone, Firth and Smith2019c).

Exposure variable: internet/email use

Frequency of internet/email use was assessed in the self-completion questionnaire, with the question ‘On average, how often do you use the internet or email?’ Response options were ‘every day, or almost every day’, ‘at least once a week (but not every day)’, ‘at least once a month (but not every week)’, ‘at least once every three months’ or ‘never’.

Those who responded that they accessed the internet/email more than every three months were asked about the devices they used to access the internet: ‘On which of the following devices do you access the internet?’ Response options included desktop computer, laptop computer, tablet (e.g. iPad, Samsung Galaxy Tab), smartphone (e.g. iPhone, Android phone), other device, or do not access internet. In addition, participants were asked ‘For which of the following activities did you use the internet in the last three months? Tick all that apply’. Response options included ‘sending/receiving emails’, ‘telephoning over the internet/video calls (via webcam) over the internet’, ‘searching for information for learning, research, fact finding’, ‘finances (banking, paying bills)’, ‘shopping/buying goods or services’, ‘selling goods or services over the internet e.g. via auctions’, ‘use social networking sites (Facebook, Twitter, MySpace)’, ‘creating, uploading or sharing content (YouTube, blogging or Flickr)’, ‘news/newspaper/blog websites’, ‘streaming/downloading live or on demand TV/radio (BBC iPlayer, 4OD, ITV Player, Demand 5), music (iTunes, Spotify), or eBooks’, ‘games’, ‘looking for jobs or sending a job application’, ‘using public services (e.g. obtaining benefits, paying taxes)’, ‘other’ or ‘none of the above’.

Covariates

Covariates were selected a priori on the basis of previous studies showing associations between these variables and the exposure and outcomes of interest. Covariates assessed in this study were age and sex, as they are both independently associated with differences in internet use (Hogeboom et al., Reference Hogeboom, McDermott, Perrin, Osman and Bell-Ellison2010; Choi and Dinitto, Reference Choi and Dinitto2013; Berner et al., Reference Berner, Aartsen and Deeg2017; Bol et al., Reference Bol, Helberger and Weert2018; Office for National Statistics, 2018a; Quintana et al., Reference Quintana, Cervantes, Sáez and Isasi2018), loneliness and social isolation (Kobayashi and Steptoe, Reference Kobayashi and Steptoe2018). Sex was reported as male or female. Age was input in categories of 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80–89 and 90+ years. Marital status (married/living as married versus single) has also been associated with internet use (Hogeboom et al., Reference Hogeboom, McDermott, Perrin, Osman and Bell-Ellison2010; Berner et al., Reference Berner, Aartsen and Deeg2017), social isolation and loneliness (Peplau, Reference Peplau, Sarason and Sarason1985; Grenade and Boldy, Reference Grenade and Boldy2008; Steptoe et al., Reference Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos and Wardle2013b; Hawkley and Kocherginsky, Reference Hawkley and Kocherginsky2017; Kobayashi and Steptoe, Reference Kobayashi and Steptoe2018). Socio-economic status (SES) was assessed using household non-pension wealth as this has been identified as an appropriate indicator of SES in older adults (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Karlsen and Oldfield2004) and used in previous studies utilising the ELSA data-set (Hamer et al., Reference Hamer, de Oliveira and Demakakos2014; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Gardner, Fisher and Hamer2015; Quintana et al., Reference Quintana, Cervantes, Sáez and Isasi2018; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Firth, Firth, Veronese, Gorely, Grabovac, Yang and Smith2019a, Reference Jackson, Hackett and Steptoe2019b). This was entered as a covariate as it has previously been associated with internet use (Hogeboom et al., Reference Hogeboom, McDermott, Perrin, Osman and Bell-Ellison2010; Berry, Reference Berry2011), social isolation and loneliness (Choi and Dinitto, Reference Choi and Dinitto2013; Steptoe et al., Reference Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos and Wardle2013b; Kobayashi and Steptoe, Reference Kobayashi and Steptoe2018).

Limiting long-standing illness has previously been associated with internet use (Hogeboom et al., Reference Hogeboom, McDermott, Perrin, Osman and Bell-Ellison2010; Choi and Dinitto, Reference Choi and Dinitto2013), social isolation and loneliness (Grenade and Boldy, Reference Grenade and Boldy2008). Participants were asked if they had any long-standing (meaning anything that has troubled them over a period of time, or that is likely to affect them over a period of time) illness, disability or infirmity. Response options were yes or no. Those answering yes were then asked if these illness(es) or disability(ies) limit their activities in any way. Response options were yes or no. Participants responding yes to the second question were categorised as having a limiting long-standing illness, otherwise participants were categorised as not having a limiting long-standing illness.

Depression has been associated with internet use (Cotten et al., Reference Cotten, Ford, Ford and Hale2012, Reference Cotten, Ford, Ford and Hale2014), social isolation and loneliness (Perlman and Peplau, Reference Perlman, Peplau, Peplau and Goldston1984; Peplau, Reference Peplau, Sarason and Sarason1985; Cacioppo et al., Reference Cacioppo, Hughes, Waite, Hawkley and Thisted2006, Reference Cacioppo, Hawkley and Thisted2010; Cornwell and Waite, Reference Cornwell and Waite2009b; Coyle and Dugan, Reference Coyle and Dugan2012; Victor and Yang, Reference Victor and Yang2012; Cotten et al., Reference Cotten, Anderson and McCullough2013; Domenech-Abella et al., Reference Domenech-Abella, Lara, Rubio-Valera, Olaya, Moneta, Rico-Uribe, Ayuso-Mateos, Mundo and Haro2017) in older adults so was included as a covariate. The eight-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to identify people at risk of depression, although one question was excluded to avoid overlap with loneliness scores meaning a total of seven questions were used; scores were dichotomised as high risk ⩾3 and low risk <3, in line with previous literature (Turvey et al., Reference Turvey, Wallace and Herzog1999; Steptoe et al., Reference Steptoe, Shankar, Demakakos and Wardle2013b; Kobayashi and Steptoe, Reference Kobayashi and Steptoe2018; White et al., Reference White, Zaninotto, Walters, Kivimäki, Demakakos, Biddulph, Kumari, De Oliveira, Gallacher and Batty2018). Questions included: ‘(much of the time during the past week) you felt depressed, you felt that everything you did was an effort, your sleep was restless, you were happy, you enjoyed life, you felt sad, you could not get going?’, to which participants could respond yes or no. The CES-D has acceptable psychometric properties in older adults (Cosco et al., Reference Cosco, Lachance, Blodgett, Stubbs, Co, Veronese, Wu and Prina2019).

Physical activity was entered as a covariate as individuals who are socially isolated and/or lonely tend to be less physically active (Lauder et al., Reference Lauder, Mummery, Jones and Caperchione2006; Hawkley et al., Reference Hawkley, Thisted and Cacioppo2009; Hawkley and Kocherginsky, Reference Hawkley and Kocherginsky2017; Kobayashi and Steptoe, Reference Kobayashi and Steptoe2018). Currently, there is no literature on associations of physical activity and internet use in older adults. Level of physical activity was assessed at interview with questions on the frequency of mild, moderate and vigorous physical activity in which the participants engaged. Responses included ‘more than once a week’, ‘once a week’, ‘one to three times a month’ and ‘hardly ever or never’. It was not possible to calculate and then dichotomise physical activity based on the recommended guidelines of 150 minutes per week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, due to the information available from the ELSA Wave 8 data-set. Responses were dichotomised as physically active if moderate and/or vigorous intensity physical activity once or more a week and inactive as less than once a week, in line with previous literature in this cohort regarding physical activity and health outcomes (Hamer et al., Reference Hamer, Molloy, de Oliveira and Demakakos2009, Reference Hamer, Lavoie and Bacon2014; Demakakos et al., Reference Demakakos, Hamer, Stamatakis and Steptoe2010; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Gardner, Fisher and Hamer2015; Kobayashi and Steptoe, Reference Kobayashi and Steptoe2018).

Statistical analysis

Data were weighted to correct for sampling probabilities and non-response to the self-completion questionnaire. Characteristics of the study population, devices used to access the internet and online activities were summarised using descriptive statistics. Differences in covariates, devices and internet activities according to internet/email use were analysed using Pearson's chi-square analysis. Differences in devices and internet activities according to loneliness and social isolation were also analysed using Pearson's chi-square analysis. Results were presented as p values with Cramer's V effect sizes. Binomial logistic regressions were used to analyse associations between internet/email use and social isolation and loneliness, and were adjusted for covariates listed above. Daily use was chosen as the reference group as it was hypothesised that this group would be lowest risk. Results were reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95 per cent confidence intervals (95% CI). All data were analysed in IBM SPSS Statistics v24. Statistical significance was accepted at p ⩽ 0.05.

Results

The initial sample comprised 8,445 older adults, however, the exclusion of older adults with missing data resulted in a final analytical sample of 4,492 men and women (mean age = 64.3, standard deviation = 13.3; 51.7% males). The majority of older adults reported using the internet/email every day (69.3%), fewer participants reported once a week (8.5%), once a month (2.6%), once every three months (0.7%), less than every three months (1.5%) and never (17.4%). Overall, 19.4 per cent of the sample reported high levels of loneliness and 32.9 per cent were classified as socially isolated.

Table 1 summarises sample characteristics in relation to frequency of internet/email use. Significant differences were found in all characteristics when comparing internet/email use groups. Compared with less-frequent users, older adults who used the internet/email every day were more likely to be younger, male, married/living as married, in richer SES quintiles, have no limiting long-standing illness, exhibit high levels of depressive symptoms, be physically active, not lonely and not socially isolated. Those never using the internet/email were more likely to be older, female, married/living as married, in the poorest SES quintile, have a limiting long-standing illness, exhibit high levels of depressive symptoms, be physically active, not lonely but socially isolated. Although both every day and never users were more likely to be married/living as married, have high depression and be physically active, never users had a higher proportion of people who were single, had high levels of depression and were physically inactive compared with every day users. Compared with other frequencies of internet/email use, those who reported using the internet/email once every three months had the highest prevalence of loneliness and social isolation.

Table 1. Sample characteristics in relation to internet/email use

Notes: Values are number of participants (percentages) within each category of internet/email frequency use unless otherwise stated. SD: standard deviation. SES: socio-economic status.

Unadjusted logistic regressions found once a week users were significantly less likely to experience loneliness than every day users (OR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.52–0.76) and the same was found when only adjusting for social isolation (OR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.63–0.92); however, this became non-significant when adjusted for covariates (OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.89–1.37) (Table 2). Less than once every three months users were significantly more likely to be lonely when adjusting for covariates (OR = 2.49, 95% CI = 1.05–5.90), but became non-significant when additionally adjusting for social isolation. No significant associations were found between other frequencies of internet/email use and loneliness in either the unadjusted or any adjusted regression model.

Table 2. Older adults’ frequency of internet/email use in relation to self-reported loneliness

Notes: 1. Unadjusted. 2. Adjusted for social isolation. 3. Adjusted for covariates sex, age, wealth, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, marital status, limiting long-standing illness, depression. 4. Adjusted for social isolation and covariates sex, age, wealth, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, marital status, limiting long-standing illness, depression. OR: odds ratio. CI: confidence interval. Ref.: reference group.

In the unadjusted and all adjusted models, once a week (adjusted for loneliness and covariates OR = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.49–0.72) and once a month users (adjusted for loneliness and covariates OR = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.45–0.80) were significantly less likely to be socially isolated than every day users (Table 3). In contrast, those using the internet less than once every three months were more likely than every day users to experience high levels of social isolation, but only in the covariate adjusted and loneliness plus covariate adjusted model (adjusted for loneliness and covariates OR = 2.87, 95% CI = 1.28–6.40). Never users in the unadjusted and loneliness adjusted models were less likely to be socially isolated than every day users (unadjusted OR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.30–0.87; loneliness adjusted OR = 0.50, 95% CI = 0.29–0.85), however, this became non-significant when covariates were adjusted for. Once every three months were no more likely than every day users to experience high levels of social isolation in any of the adjusted or unadjusted models (adjusted for loneliness and covariates OR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.61–1.45).

Table 3. Older adults’ frequency of internet/email use in relation to self-reported social isolation

Notes: 1. Unadjusted. 2. Adjusted for loneliness. 3. Adjusted for covariates sex, age, wealth, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, marital status, limiting long-standing illness, depression. 4. Adjusted loneliness and covariates sex, age, wealth, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, marital status, limiting long-standing illness, depression. OR: odds ratio. CI: confidence interval. Ref.: reference group.

Among all older adults, the tablet (47.5%), smartphone (47.4%) and laptop (47.0%) were the most commonly mentioned devices used to access the internet/email (Table 4). Every day users were most likely to use a smartphone compared to less-frequent users, whereas a laptop was most commonly used among less-frequent users. Significant differences between internet/email use frequency and the devices used to access the internet among all devices were found.

Table 4. Devices used to access the internet in the last three months categorised by internet/email usage

Note: Values are number of participants (percentages) within each category of internet/email frequency use unless otherwise stated.

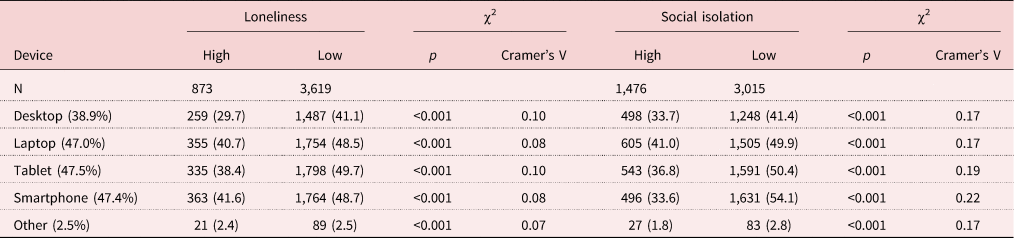

Smartphones were the most commonly reported device used among those with high loneliness (41.6%) and low social isolation (54.1%), whereas a tablet was most common in those with low loneliness (49.7%) and a laptop amongst those who were socially isolated (41.0%) (Table 5). Weak associations were found between all devices and loneliness, however, strong associations were found for social isolation.

Table 5. Older adults’ device use in relation to loneliness and social isolation

Note: Values are number of participants (percentages) within each category of loneliness/social isolation unless otherwise stated.

Searching for information, sending/receiving emails and shopping/buying were the three most common internet activities in the last three months among all participants, and even when split by internet/email frequency use (Table 6). However, every day users more frequently reported sending/receiving emails than searching for information. Significant differences between the frequency of internet/email use groups were seen among all internet activities.

Table 6. Internet activities in the last three months categorised by internet/email usage

Note: Values are number of participants (percentages) within each category of internet/email frequency use unless otherwise stated.

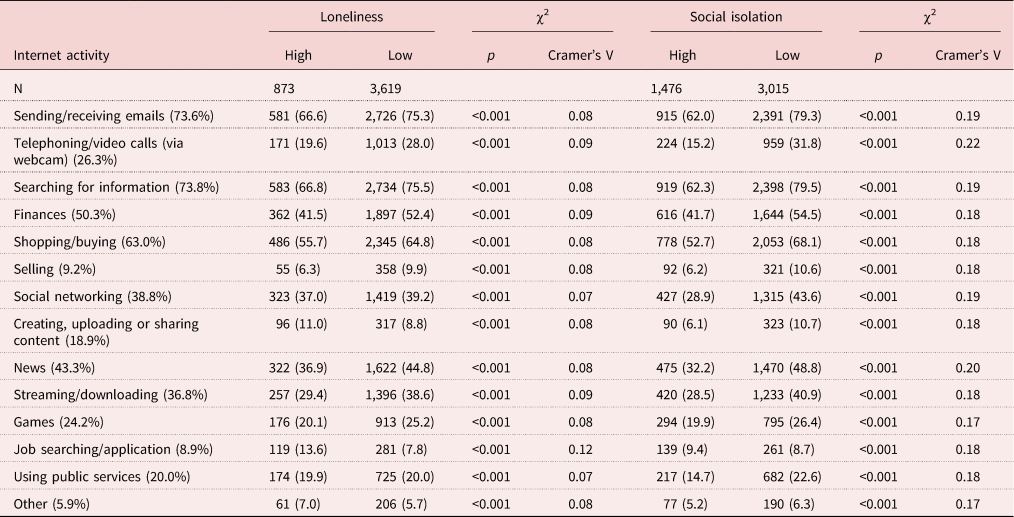

Weak associations were found between loneliness and all types of activities engaged with online, excluding job searching/application which showed moderate association with loneliness (Table 7). All online activities were strongly associated with social isolation status. A larger proportion of those with low loneliness engaged with most of the online activities compared with the proportion of those with high loneliness, excluding creating, uploading and sharing content (high = 11.0%; low = 8.8%), job searching/application (high = 13.6%; low = 7.8%) and other online activities (high = 7.0%; low = 5.7%). The same was true in job searching/application for social isolation status (high = 9.4%; low = 8.7%).

Table 7. Older adults’ internet activities in the last three months in relation to loneliness and social isolation

Note: Values are number of participants (percentages) within each category of loneliness/social isolation unless otherwise stated.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore associations between internet/email use in a large sample of older English adults with their social isolation and loneliness. The use of internet/email was highly prevalent in the study population; 69.3 per cent of older adults (⩾50 years) use the internet/email every day and 77.8 per cent at least once a week. This means that using the internet/email as a method to deliver behaviour change interventions (e.g. physical activity, dietary, smoking cessation) has potential in this population, particularly those who may be harder to reach such as those who are socially isolated, without much additional cost.

No associations between frequency of internet/email use and loneliness were found in the present study when adjusted for covariates and social isolation; however, previous studies found greater use of the internet was associated with lower loneliness in older adults (Erickson and Johnson, Reference Erickson and Johnson2011; Cotten et al., Reference Cotten, Anderson and McCullough2013; Heo et al., Reference Heo, Chun, Lee, Lee and Kim2015; Chopik, Reference Chopik2016), as measured by the 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Peplau and Cutrona1980), three-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, Reference Russell1996) or the 11-item short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys (Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Waite, Hawkley and Cacioppo2004). One explanation for the null findings in the present study may be that loneliness is perceived by some older adults as a complex and private matter (Kharicha et al., Reference Kharicha, Iliffe, Manthorpe, Chew-Graham, Cattan, Goodman, Kirby-Barr, Whitehouse and Walters2017), so self-completion questionnaire answers may not reflect true feelings of loneliness. The three-item UCLA questionnaire to measure loneliness was selected to minimise this in the present study, rather than using the direct questions available in the ELSA data-set that explicitly mention loneliness (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2015). In addition, the UCLA three-item questionnaire only uses negative wording in the questions which may lead to participants providing the same answer for each question without properly considering what they are being asked (Campaign to End Loneliness, 2015). Equally, the use of different measures of loneliness may also provide reasoning for the different findings between previous studies and the present study.

A previous study found older adults’ online communities were most heavily used on afternoon weekdays, and fewer interactions occurred at weekends or during the Christmas holidays (Nimrod, Reference Nimrod2010). This suggests that when face-to-face interactions are available (e.g. with family members who work full-time), older adults choose these over online communities. Therefore, loneliness may only be associated with time spent with real-world connections, rather than online connections in older adults, hence the null findings in the present study. Loneliness in older adults is related to the quality rather than quantity of relationships (Holt-Lunstad et al., Reference Holt-Lunstad, Smith and Layton2010; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Cutrona, McRae and Gomez2012; Beneito-Montagut et al., Reference Beneito-Montagut, Cassián-Yde and Begueria2018), and relationships among older adults in online communities seem mostly superficial and rarely extend to offline domains (Nimrod, Reference Nimrod2010), so there is also potential that the objective measure of frequency of internet/email use in the present study has no bearing on the quality of a relationship for older adults.

The types of activities engaged in whilst online may, however, impact loneliness. In the present study, weak associations were found between most online activities and loneliness status. Loneliness was previously significantly negatively correlated with internet use for communication among older adults, whereas internet use for information, entertainment or total internet use was not correlated with loneliness, measured with the 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Erickson and Johnson, Reference Erickson and Johnson2011). In older adults (⩾52 years) Facebook use was not associated with loneliness, measured with the 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Fausset, Farmer, Nguyen, Harley and Fain2013), which although it could be seen as a communication tool, may suggest older adults use Facebook for other reasons such as entertainment or information. Video calls are a useful tool for overcoming barriers to connect people who cannot meet face to face (e.g. geographic distance, time constraints) (Khalaila and Vitman-Schorr, Reference Khalaila and Vitman-Schorr2018), however, they mostly foster established relationships, rather than creating new ones. Elderly residents of a nursing home showed significantly lower loneliness scores, measured using the 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale, after three months of video-conferencing with relatives for five minutes per week (Tsai et al., Reference Tsai, Wang, Chang and Chu2010). Previous research showed the number of outgoing telephone calls was not associated with loneliness in older adults, however, the number of incoming calls was negatively associated with loneliness (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Thielke, Austin and Kaye2016b), measured using the 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Peplau and Cutrona1980). Communicating via the internet with family and friends has been shown to reduce older adults’ (⩾55 years) feelings of loneliness (Sum et al., Reference Sum, Mathews, Hughes and Campbell2008), measured using the Social and Emotional Loneliness Scale (DiTommaso et al., Reference DiTommaso, Brannen and Best2004), which may suggest the type of online activity and the relationship with whom they are communicating may be an important factor. Future studies should therefore consider investigating the quality of these online and offline relationships when researching loneliness.

Older adults using the internet/email once a week or once a month were less likely to be socially isolated than every day users. Conversely, a previous study found that social isolation was reported less frequently in older adults using the internet every day compared with never and sometimes users (Lelkes, Reference Lelkes2013). A previous study that gave older adults computers with internet access for three years found that participants were able to stay in touch with their real-world contacts whilst suffering illness (Fokkema and Knipscheer, Reference Fokkema and Knipscheer2007). Thus, it may be that participants in the present study who are unable to reduce their social isolation, however, remain in contact with the outside world through these means (Chen and Schulz, Reference Chen and Schulz2016). There is also the possibility that it may encourage isolation due to convenience.

In a similar way to loneliness, explanations for the associations between social isolation and frequency of internet/email use may come from specific online activities. Strong associations were found between social isolation and all online activities in the present study. Communicating with family and friends via the internet reduced older adults’ (⩾55 years) social isolation, but when used often, for long durations and to communicate with strangers was associated with greater social isolation (Sum et al., Reference Sum, Mathews, Hughes and Campbell2008). Therefore, using internet/email as complementary, rather than replacement, of face-to-face social meetings may protect against social isolation and potentially loneliness (Fokkema and Knipscheer, Reference Fokkema and Knipscheer2007; Cornejo et al., Reference Cornejo, Tentori and Favela2013; Lelkes, Reference Lelkes2013). Another explanation for the findings in the present study could be that every day users may either be online too frequently and/or for long durations, which may lead to greater social isolation. Once a week and once a month users in the present study may have a better balance, e.g. they are too busy with real-world contacts and activities to spend as much time online, leading to reduced social isolation. Future interventions targeting social isolation in older adults may utilise the internet for cost-effectiveness, however, in addition to real-world interactions to reduce the increased risk of loneliness. Previous research suggests that sharing content online can enhance conversations and promote real-world interactions that strengthen older adults’ networks, particularly intergenerationally (Cornejo et al., Reference Cornejo, Tentori and Favela2013). Future research should consider exploring the frequency and duration of internet use, in addition to online activities, when exploring associations with social isolation and loneliness.

Those using internet/email less than once every three months were more likely to be socially isolated than every day users. Explanations for this could be poor access to internet/email services, lack of internet/email education or even a purposeful decision to live ‘offline’. Future digital interventions should thus consider the frequency and duration of use and time spent in face-to-face interactions to ensure quality relationships are fostered/maintained in order to reduce social isolation and feelings of loneliness in older adults.

One limitation of the present study is the data are self-reported, which although useful for gathering sensitive information such as loneliness and social isolation, may include bias and potential under- or overestimations of reported behaviours (Prince et al., Reference Prince, Adamo, Hamel, Hardt, Connor Gorber and Tremblay2008; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Macfarlane, Lam and Stewart2011; Scharkow, Reference Scharkow2016; Araujo et al., Reference Araujo, Wonneberger, Neijens and de Vreese2017). When split by frequency of internet/email use, some groups include low numbers of participants, which may potentially lead to type 1 statistical error. One purpose of internet use involves communication with others, which was also captured in the social isolation measures including written/email/text messaging contact, therefore there may be some overlap between these variables. In addition, the single-item question relating to internet/email use may not provide enough information to gain true insight into the duration of time spent online, via which device and for which activities. Therefore, future studies should aim to elicit more detailed information, including duration of use per day as total time and in bouts of use, in self-report questionnaires on technology use. The present study explores associations, and whilst speculations can be made, causation regarding internet use, social isolation and loneliness in older adults requires further research.

Conclusion

The present study found older adults’ perceived loneliness is not associated with their frequency of internet/email use; however, social isolation is associated with frequency of internet/email use, but not linearly. This suggests that internet use bears no impact on the perceived quality of relationships for older adults and is often used to keep contact with established real-world connections. The study also highlights that 69 per cent of older adults use the internet/email every day and 78 per cent at least once a week, and that smartphones and tablets are more popular with every day users whereas less-frequent users tend to use laptops or tablets. This may have important implications for future digital behaviour change interventions for health, specifically in older adults.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was obtained from the London Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee and all participants provided full informed consent.