Introduction

The quality of care practices is still a central issue for long-term care (LTC) policy and care workers’ working conditions are recognised in recent literature as determinants of quality care (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2013a; Shulmann et al., Reference Shulmann, Gasior, Fuchs and Leichsenring2016; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Rodrigues and Leichsenring2018; Hussein, Reference Hussein2018).

The need to focus on quality care practices is crucial due to several factors. Firstly, Europe's population is ageing rapidly. The global population of older people (>65) in the European Union (EU) in 2016 was 19.2 per cent (Eurostat, 2019) and will rise to 30 per cent by 2050. Secondly, the population aged 80 or above is projected to almost triple to 10 per cent by 2050 and the group of the oldest-old is likely to require more institutional care, tending to have cognitive impairments or require help with their physical needs.

Demographic changes and the increase in the participation of women in the labour market has led to so-called care gaps, raising a central concern: what trained and qualified resources meet the growing formal and informal care-giving needs?

LTC is defined as a labour-intensive sector, which includes person care and assistance services. Formal care is a complement to informal, unpaid work, in supporting people who are dependent on help with basic and/or instrumental activities of daily living for an extended period of time (more than six months) (Rodrigues, Reference Rodrigues, Ferreira, Cabral and Moreira2017; European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs 2018) . Both concepts, formal and family care, are integrated within the broad category of care work.

Pressure for increased public provision and financing of LTC services may grow substantially in the coming decades, especially in those EU Member States where the bulk of care is currently provided informally. A large proportion of care in the EU is actually provided by informal carers such as family members and friends – mainly spouses and children (Gil, Reference Gil2010; Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Huber and Lamura2012; Verbakel et al., Reference Verbakel, Tamlagsrønning, Winstone, Fjær and Eikemo2017).

The International Labour Office (ILO) estimates that globally more than 50 per cent of older persons do not have access to needed LTC services, given the absence of the required workforce (Scheil-Adlung and ILO, 2015). The LTC workforce represents ‘over 60 per cent of the total employment in long-term care’ (ILO, 2018: 180). Due to staff shortages, the majority of older persons in need of LTC receive services from family members filling the gaps in the health and social care workforce (Scheil-Adlung, Reference Scheil-Adlung2016). The availability of informal care will remain a key factor influencing future demand for formal services (Cangiano and Shutes, Reference Cangiano and Shutes2010) and the analysis cannot be dissociated from formal care (home-care services and institutional care).

Caring for someone over a long period is known to affect carers’ health, participation in the labour market, financial status and social integration (Gil, Reference Gil2010, Reference Gil2018; Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Huber and Lamura2012; Yeandle, Reference Yeandle2016). These impacts also extend to care work, and care practices should be evaluated according to residents’ care needs but also the needs of care workers. Both are indispensable in ensuring people's access to quality care. However, little or no attention has been accorded by policies to the conditions under which care workers provide care – their job and income security, health and safety, care workers’ own family responsibilities (King-Dejardin, Reference King-Dejardin2019) and employment conditions (contracts, pensions, national insurance, holiday and sick pay) (Woolham et al., Reference Woolham, Norrie, Samsi and Manthorpe2019; Gil, Reference Gil2020).

The ILO (2018) has claimed that it is important to look at the dynamic intersection of informal and formal care to explain the impact on working conditions of care workers. The ILO (2018: 10) named the model the ‘unpaid care work–paid work–paid care work circle’. The availability of family care and the access to care services depend on the levels of employment and the working conditions, and affect, particularly, women. Gender inequality emerges as the central issue in the relationship between paid care work and unpaid care work.

In this intersection between informal and formal care, the concept of care regimes is an important analytical approach for differentiating the variety of policy frameworks that exist in LTC care systems: the universal system of care, the mixed solidarity model, the familist model and an emerging model.

Mediterranean countries are integrated in the familist model, which stands for the traditional caring responsibilities, mostly by women, and is characterises by the underdevelopment of formal care (Simonazzi, Reference Simonazzi2008; Bettio and Verashchangina, Reference Bettio and Verashchangina2012; Salis, Reference Salis2014; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 2019).

In Europe, there are a variety of regimes and policy changes, in public policies of LTC and in the formalisation of family care (Bouget et al., Reference Bouget, Spasova and Vanhercke2016; European Commission, 2018), to meet the growth of care needs. Even so, precarious working conditions seem to be a common denominator across Europe (OECD, 2020).

Taking Portugal as an example of a country where informal (unpaid care work) and formal care (paid work care) are connected, this paper aims to answer two specific questions: firstly, what is the interdependency between unpaid care work and paid care work; and, secondly, what are the individual, interpersonal and organisational determinants that most influence quality care.

Portugal has been pointed out as one of the European countries where the size of the LTC workforce is the smallest but where its growth rate is high (OECD, 2020). Based on this finding, this article intends qualitatively to go further and explore the profession's itinerary, both in terms of the legal framework and in terms of labour statistics.

In Portugal, the term ‘care worker’ is used to designate a paid carer who is defined as the person who possesses a contractual link, who accompanies the older person within an institution or at their home, performing personal and instrumental activities, and specialised care, such as mobilisation, incontinence management, on a regular basis throughout the day. The legal framework of the care worker profession was defined, in the 1980s, with the designation of ‘family assistant’, as someone who provides care, tasks conceived, at the time, as the family's responsibility. The legal itinerary shows that the care worker emerges as the family's helper and not as a profession with its own identity and competences.

This paper presents the results of an ongoing research project ‘Ageing in an Institution: An Interactionist Perspective of Care’. A multi-method study was developed, with the aim of analysing the relationships between the organisation of nursing homes, the interpersonal features of care providers and their relation with home residents’ quality of life. The project involved data collection in 16 nursing homes. Interviews were conducted with different actors in order to compare the perspectives of managers, nursing care workers, professional staff and residents. The focus of this article is on the perspectives of care workers, their daily experiences and professional trajectories. Through the narratives of care workers and based on the care trajectory concept, proposed by Corbin (Reference Corbin1992) and developed by Hayes (Reference Hayes2017), this article intends to explore the interdependency between unpaid care work and paid care work. Both concepts, paid and unpaid work, are conceived as part of a continuous and integral part of the care work process, which can be influenced by individual, interpersonal and organisational determinants, with direct consequences on quality of care.

Conceptualising care work trajectories

Corbin (Reference Corbin1992) defined the care-giving trajectory as a care process that is dynamic and interactive in which social actors (care-giver/receiver, family system, community and services) intervene, encompassing various tasks, activities, competencies and negotiations that almost always appear invisible (e.g. supervising and monitoring the care receiver, and the relational aspects of care) (Keating et al., Reference Keating, Eales, Funk, Fast and Min2019).

Caring for someone who needs 24-hour assistance presupposes an intensive care work, often conceived of domestic work. It involves time, tasks, skills, knowledge, management of emotions and resources, and a permanent ‘work of conciliation’ (Guberman et al., Reference Guberman, Maheu and Maillé1992) with other family members and formal services (Gil, Reference Gil2010).

Keating et al. (Reference Keating, Eales, Funk, Fast and Min2019) conceptualise lifecourses of family care with core elements of ‘care as doing’ and ‘care as being in relationship’, creating hypothetical family care trajectories to illustrate the diversity of lifecourse patterns of care, which are influenced by institutional and social changes. The authors demonstrate how cumulative care experiences might shape lives, including professional trajectories. ‘The risk of cumulative disadvantage across a life course of care remains untested’ (Keating et al., Reference Keating, Eales, Funk, Fast and Min2019: 150) and it is important to give visibility.

Through the narratives of care workers and based on the care trajectory concept, the intention is to describe their educational and social profile, family experiences of caring, the reasons for choosing the profession, what daily care work means, what are the main impacts on their lives and how their working conditions influence care the provided and their quality aspirations.

The professionals’ trajectories are based on personal experiences, a concept that allies the emotional representation to its cognitive dimension. Dubet (Reference Dubet1994: 95) describes experience as a ‘cognitive activity, a way of constructing reality, and mostly, of verifying it, and experimenting on it’. Social experience is a way of constructing the world, in which individuals construct the meanings of their practices. By assuming that experience is socially constructed, ‘the discourse of the interviewees selects the social categories of the experience, as much as it is recognised and shared by others’ (Dubet, Reference Dubet1994: 95). The conceptual perspective also allows one to understand the way of thinking and interpret the daily reality of care workers regarding care practice experiences and how working conditions actually shape the quality of care.

The ‘unpaid care work–paid work–paid care work circle’

Decent work, job quality (proposed by Eurofound, 2017, cited by ILO, 2018), and an attractive and supportive work environment (Wiskow et al., Reference Wiskow, Albreht and Pietro2010; Gil, Reference Gil2020) are determinants that have impact on quality care in the social and health sector.

A definition that recognised that there is an interdependence between quality of care and work conditions is proposed by the ILO (2018: 12): ‘quality care means, among other things, access to affordably priced care services, provided by care workers with the necessary skills’. It means that access, price and qualification are three important dimensions of quality care. The ILO (2018: 10) designed this process as a ‘unpaid care work–paid work–paid care work circle’, when the availability and quality of care services are directly related to the levels of employment and the working conditions of care workers, and affect the supply of labour, particularly of women, increasing gender inequality.

Family care

The literature provides clear evidence that long periods of care have an impact on careers, not only on the number of hours of care, physical and mental health, employment, wages, increased risk of poverty and early retirement from the labour market (Gil, Reference Gil2010; Bouget et al., Reference Bouget, Spasova and Vanhercke2016).

A large part of the care work is provided by unpaid, often female workers who are fully or partly pulled out of the labour market to provide LTC to relatives (Gil, Reference Gil2010). In Portugal, this tendency is particularly noticeable, given that 70 per cent of informal care work is performed by women over 50 years of age (OECD, 2019a) and 21 per cent of women (50–64 years of age) (Eurostat, 2018) leave the labour market early to take care of dependent family members.

Portugal reveals high female participation in the labour market, when compared with other European countries, mainly the southern European countries, such as Italy and Greece with values of female activity below 45 per cent. In 2018, 54.4 per cent of Portuguese women aged 15 years and over were in the labour market (in 1986 the percentage was 46.5%) (Pordata, 2020). In addition, the majority of Portuguese female workers have full-time jobs (in 2018, only 12.3% had part-time jobs) (Pordata, 2020). As Portuguese women have traditionally been the main carers of older people, their increasing participation in the labour market, mostly on a full-time basis, put limits on their availability to provide care. This trend contributes to the phenomenon commonly called the ‘caring gap’ (increased demand for care for older people and decreased supply of care-givers) (OECD, 2014). The projected ‘support ratio’, i.e. the ratio of women aged 45–64 for each person aged 80 and older, has already diminished in the period (1990–2030), in Portugal, from five to two care-givers (Hoffmann and Rodrigues, Reference Hoffmann and Rodrigues2010: 5). The propensity to provide care will be affected by the participation in the labour market, as well as the availability to provide care.

To promote family care, Portugal did put in place measures to support the care recipient, in case of dependence (first generation of LTC policies) (‘allowance for dependence’) and measures to support family care-givers,Footnote 1 mainly a family allowance,Footnote 2 measures regarding contributory career and a facilitated access to care services (domiciliary services, nursing homes and National Network of Integrated Continuous Care (RNCCI).Footnote 3 However, work–life balance policies are sparse, as well as measures that promote reintegration into the labour market. Thus, the availability of informal care will remain a key factor influencing future demand for formal services.

Formal care

Despite an improvement in the availability of social services and facilities for older persons, in Portugal, the network of social responses for older people and the user capacity is not sufficient to cope with all those in need (Gil, Reference Gil2020), taking into account demographic indicators. Demographic projections suggest that the increase in people over 80 will reach 16 per cent by 2060, from 6 per cent in 2016 (European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs 2018) ), due to increasing life expectancy (84.6 for women and 78.4 for men; OECD, 2019a).

Portugal allocated 0.5 per cent of its Gross Domestic Product to the public provision of LTC, less than the average across OECD countries, in 2015 (1.7%) (Gil, Reference Gil2018, Reference Gil2020; OECD, 2019a). Low public investment in the residential sector leads to the number of places available in care homes being consequently low, within a system where the staff–resident ratios are out of step with a population already advanced in age and in need of LTC.

Staffing ratios (according to the legislation in Portugal, i.e. one for every five residents) are not compatible with the profile of the resident population: 72 per cent of these were women over 80, with severe care needs (cognitive and physical impairments) (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, 2011), a tendency also identified in the social profile of those who live in nursing homes in Portugal (72.5% aged 80+ years) (Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento, 2018).

The inadequate coverage rates led to a second issue, the exponential increase in non-licensed nursing homes in Portugal (Gil, Reference Gil2019). Families cannot afford care home fees in the private sector (which are licensed), which are outside the reach of the majority of the Portuguese population, and there are no vacancies in the non-profit sector because of the limited number of places available. A number of consequences arise from the inadequate coverage of LTC, such as the reliance on an informal care work market, the increase in unlicensed homes and a higher responsibilisation of the family, particularly of women (Gil, Reference Gil2019), and a continued demand for domestic and care workers, mostly immigrants: Brazilian, Ukrainian and Cape Verdean women (Wall and Nunes, Reference Wall and Nunes2010). This trend has persisted throughout the last decade, where the employment of foreign-born workers in domestic or residential care services has increased, respectively, by 20 and 44.5 per cent between 2008 and 2012 in the European OECD countries (OECD, 2013b).

Informal care work market

Migrant workers (middle-aged women) are employed as lower-level care workers, but sometimes have more qualifications than native-born care workers and the wages are lower (Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, Nozal, Mercier and Tjadens2011; Theobald, Reference Theobald2017). This characterisation of immigrant groups coincides with the immigration report (Reis Oliveira and Gomes, Reference Reis Oliveira and Gomes2014), where 26.7 per cent of immigrants in Portugal performed unqualified work, which means that foreign workers make up the lowest paying jobs in the job market. Unqualified work, which includes mainly domestic work, cleaning services and social care for the older population, was performed by African (Cape Verde, Angola), Romanian, Ukrainian and Brazilian immigrant groups (Reis Oliveira and Gomes, Reference Reis Oliveira and Gomes2014: 65). Immigrant care workers are employed mainly in the informal market, often as live-in carers in private households or in non-licensed private nursing homes (Gil, Reference Gil2019), and sometimes are vulnerable to exploitation, abuse and harassment (Figueiredo et al., Reference Figueiredo, Suleman and Botelho2018) due to insecurity surrounding the irregularity of their immigration status. Thus, irregular immigrants can only enter the informal labour market where low wages and poor or exploitative working conditions are more common in the private sector (Salis, Reference Salis2014).

In the last decade, in Portugal, the lack of social protection and flexibility that characterised domestic services is increasing into an underground status (Abrantes, Reference Abrantes2012).

Research in Portugal (Peixoto and Figueiredo, Reference Peixoto, Figueiredo and Malheiros2007; Wall and Nunes, Reference Wall and Nunes2010; Abrantes, Reference Abrantes2012; Figueiredo et al., Reference Figueiredo, Suleman and Botelho2018) suggests that the domestic sector is one of the main areas where immigrant women more easily find jobs, not only because there is demand for workers in the care sector, but also because it is becoming less attractive for Portuguese workers due to the poor working conditions that the formal services offer.

Portugal follows the European trend in dealing with staff shortages by developing policies to attract migrants (OECD, 2019b). The employment of female live-in care workers has increased in Europe, as well as in Portugal, mainly by immigrants from Brazil, African countries and Eastern Europe. Even though there are different patterns of migration, as well as a variety of regimes and policies, precarious working conditions seem to be a common denominator across Europe (Eurofound, 2019; OECD, 2020).

Linking undervaluing care work with working conditions

The formal care workforce is often associated with low recognition and salaries, which leads to relatively high staff turnover and staff shortages, a tendency recognised in some countries of Europe (European Commission, 2018; OECD, 2020). Inadequate ratios of care workers and poor working conditions are considered to be the main factors that contribute directly to gender equality in the world of work and to redistribute unpaid care work, according to the ILO (2018).

In several countries, the numbers of care workers relative to the population aged 65 and over is far lower than the OECD average. There are, on average, five LTC workers per 100 people aged 65 and over across 28 OECD countries. Numbers are much lower in Portugal (less than one worker per 100 people aged over 65), leading to waiting lists for access to care and insufficient capacity to meet needs (OECD, 2020).

Across 19 OECD countries, 56 per cent of LTC workers are based in institutions (OECD, 2020). In Portugal, 70 per cent of LTC workers are based in institutions and 30 per cent are nurses (OECD, 2017). The differences are increased between care workers in institutional care (0.6) and home-based care services (0.1). In 2018, the worker density in institutional care decreased in the case of nurses (0.2) and personal care workers (0.4) (OECD, 2017). Institutional care is provided by untrained and unskilled workers (64%) (OECD, 2019).

An inadequate ratio of care workers is associated with poor working conditions: excessive workloads and long working hours, high rotation of care workers, earning an hourly rate similar to the minimum wage and poorly trained (Lopes, Reference Lopes and Greve2017; Gil, Reference Gil2018). This trend is worst in the case of immigrants.

A survey in the United Kingdom (UK) showed that over 30 per cent of foreign-born care workers worked more than 40 hours a week compared to only 18 per cent of UK-born care workers; the comparative figures for shift work were 74 and 60 per cent, respectively (Cangiano et al., Reference Cangiano, Shutes, Spencer and Leeson2009: 81).

Poor working conditions lead to recruitment problems, high turnover, early retirement in the care sector (Cangiano and Shutes, Reference Cangiano and Shutes2010; OECD, 2020) and high incidence of work-related poor health (physical and mental) (Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, Nozal, Mercier and Tjadens2011). According to the OECD (2020: 111), in Mediterranean countries (Spain, Italy and Portugal), about 80 per cent of LTC workers report exposure to physical risks, while about 40 per cent report exposure to mental wellbeing risk factors.

Different strategies have been implemented in several European countries to deal with staff shortages. Adequate working conditions, quality supervision, social support and social recognition are measures important for safeguarding workers’ wellbeing and ensuring the quality of care delivery (Gil, Reference Gil2018; Hussein, Reference Hussein2018). Some countries have opted to rejuvenate and requalify the workforce in the care sector. In England, the stand-out measures include: support with travel costs, opportunities to obtain qualifications, supporting older care workers (60–75 years old), and offering opportunities for workers to continue active employment combined with more flexible work arrangements (Hussein, Reference Hussein2010; Hussein and Manthorpe, Reference Hussein and Manthorpe2010, Reference Hussein and Manthorpe2012).

In some OECD countries, initial vocational training for LTC is publicly financed, although in some, there is a mix of public programmes with national certification, and private funding (Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, Nozal, Mercier and Tjadens2011: 165).

In Germany, some examples of measures to increase professionalisation are programmes providing three years of occupational training, the definition of qualification standards and a 50 per cent quota of skilled staff being required by law in residential care services (Theobald, Reference Theobald2017).

Although there is a diversity of programmes, curricula for the LTC sector show little development, especially in the case of lower-level care workers (Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, Nozal, Mercier and Tjadens2011) and their impact on quality care practices, which can be an area for further investigation.

Some countries have attempted to deal with staff shortages by developing policies to attract migrants. However, this strategy can help mitigate short-term shortages, but the extent to which migrants may compensate for staff shortages in the longer term is unclear (European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs 2018) 2018) and depends on the country's care regime (Anderson, Reference Anderson2012; Salis, Reference Salis2014; King-Dejardin Reference King-Dejardin2019) . The migrants’ employment setting differs across countries and their working conditions become harder in countries with a less well-developed public care sector, such as Portugal.

Methods

Participants

This study was carried out in one council in the metropolitan area of Lisbon and included different actors’ perspectives: managers, professional staff and residents. Although the study included interviews and observation of daily life, the focus of this article centred on care workers’ perspectives.

An official partnership agreement was made between the institution (NOVA.FCSH), the City Hall of the council and the local Social Services, regarding the use of the data (only for study) and respecting the confidentiality and anonymisation of data.

In the scope of this social network we invited, by post, all the nursing homes located in rural, semi-urban and urban civil parishes, followed by a personal phone call to explain and plan the fieldwork. Forty nursing homes (for-profit and not-for-profit) were invited to participate and 16 agreed to participate.

Data analysis

The data shown in this article include: (a) employment statistics from the Strategy and Planning Office; (b) analysis of laws/regulations; and (c) 40 interviews with care workers.

Employment statistics from the Strategy and Planning Office

The use of employment statistics, from the Strategy and Planning Office within the Ministry of Solidarity, Employment and Social Security, provides a profile of Portuguese care workers. Socio-demographic variables were restricted to sex, age, qualification, working hours per week and salary. The data have limitations because they do not encompass the totality of care workers working in nursing homes, leaving aside those working for unlicensed homes. The statistics are not available to the public and therefore were acquired as a service purchase for research purposes. It was not possible to carry out any quantitative data analyses since access to the original database was not available. Despite the percentages of the OECD (2019a), the data do not estimate the real number of care workers in Portugal. The preliminary results allowed me to characterise and quantify the Portuguese care workforce in the non-profit sector.

Analysis of laws/regulations

This paper provides an overview of the legal framework of the care worker profession in Portugal, in order to identify the main social changes that occurred in the profession. Based on a documental and historical analysis, 11 regulations were identified. A content analysis of Portuguese laws was carried out, from 1989 to 2018, focusing on the care tasks required, competences profile defined, recruitment criteria and training content required, and career prospects.

Care workers’ interviews

The aim of the care workers’ interviews was to obtain data on organisational features of the settings, focused on: personal and professional trajectories, the organisational definition of care; impacts and problems associated with care work; factors influencing quality care; and solutions to requalifying the care worker profession.

The majority of the interviewees were women, aged between 24 and 64 years, and the average time working in the profession was 10 years. Educational background varied between primary education (4th grade) and the 12th grade of high school.

All interviews were recorded (E1 to E40) and fully transcribed (interviews lasted between 30 and 90 minutes). The transcription and English translation of the quotations is intended to preserve the original form of the oral language used by participants to share their experiences and trajectories of care work.

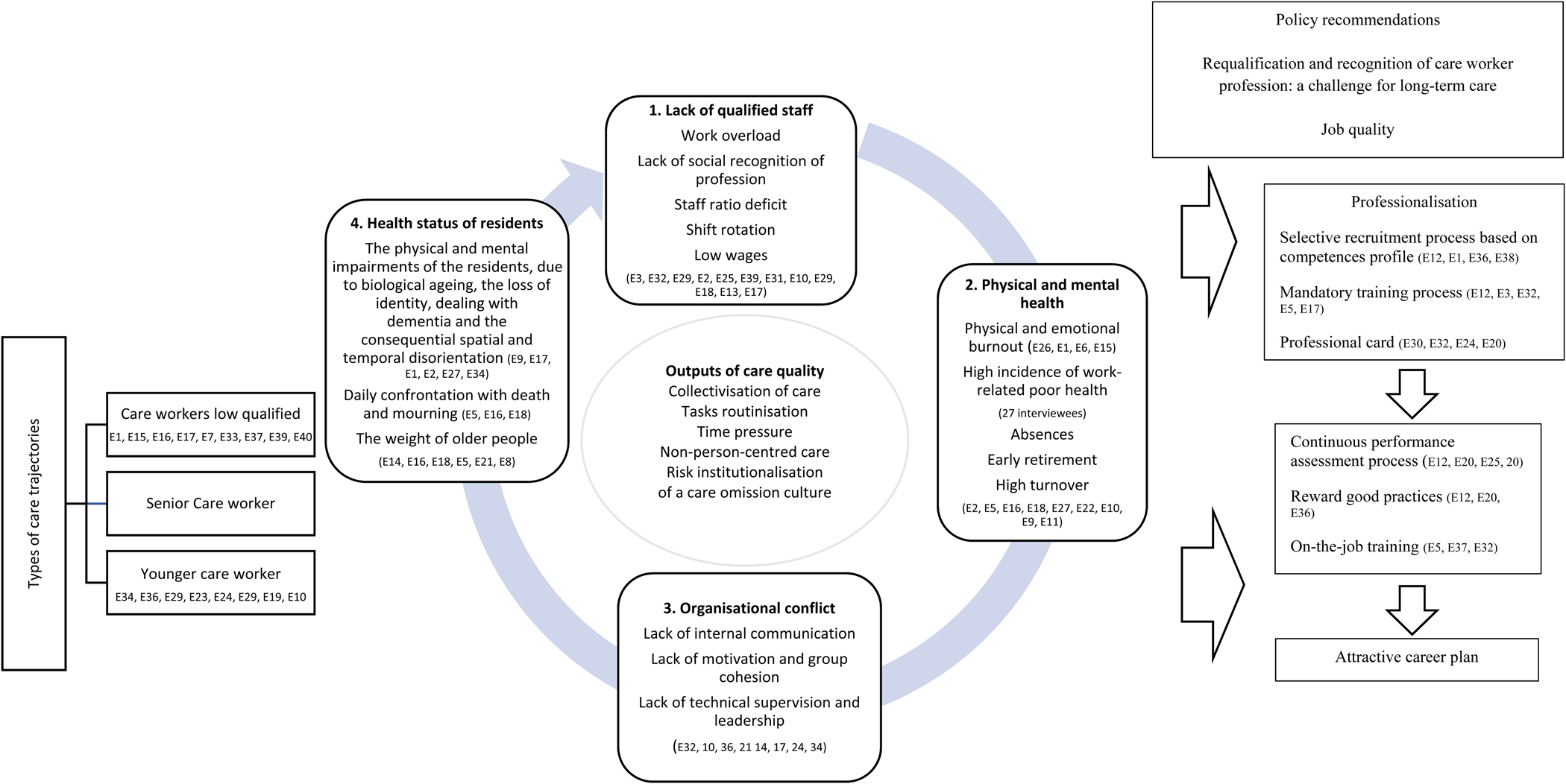

A three-stage thematic content analysis was used: (a) the process of assigning categories and sub-categories reflecting previously defined core themes as a guiding framework (trajectories of care, working conditions and care quality) as well as new ones (Figure 1); (b) the compilation of all excerpts from the text subordinate to the same category in order to permit comparison and identify segments that could intersect care quality and working conditions; and (c) through an analytical induction method, exploring with in-depth categorical and theoretical-substantive coding categories (Miles et al., Reference Miles, Huberman and Saldana2014; Gil, Reference Gil2018, Reference Gil2020).

Figure 1. Care work circle of determinants.

After coding all text segments, the coded passages were organised according to meaning units and the analytic framework focused upon discursive meanings, perceptions of care trajectories and experiences of care workers. The data analysis aim was to shed light on the fundamental complementarities and contradictions between decent care and decent work. Therefore, the data focused on the relation between work conditions and quality care, and a set of factors were identified in the process of care: impacts on individual dimension (the confrontation with residents’ dementia; their physical and mental health); organisational system dimension (lack of care workers, low wages and absenteeism, alternate shifts, inadequate ratio) and quality aspirations. Throughout the process, the coded passages were compared and placed back in the context of the original transcripts in order to verify consistency and the analyses focusing on those factors.

Results

Personal care workers: an invisible profession in Portugal

The legal framework of care worker profession was defined, during the 1980s, with the designation of ‘family assistant’. According to Ordinance No. 98/1989, the family assistant's role is to:

(a) provide assistance with meal confection, handling clothing as well as hygiene care and personal comfort of the user; (b) perform outdoors services necessary to the users as well as accompanying them in their travels, whenever necessary; (c) administer to the user, when necessary, the prescribed medication that is not of the exclusive competence of health professionals; (d) to keep up with changes that may occur in the user's overall situation that affect their wellbeing and act in order of overcoming possible situations of isolation or loneliness. (Ordinance No. 98/1989: article 2)

The start points of this activity assumed the mandatory attendance of theoretical/practical training sessions, in which were included basic notions of gerontology and the issue of dependence, nutrition and safety, domestic economy, mobilisation techniques, personal care and human relations (Ordinance No. 98/1989: article 7).

Initially defined with the term ‘family assistants’, from 1999 it was designated as ‘care assistants’ (Decree No. 414/99 of 15 October 1999). Despite some efforts by the state to ensure that care workers receive training and have the skills necessary to provide care, during the 1990s a new care worker category was created, ‘care assistants’ (Auxiliar de Ação Direta), with a specific profile that ‘he/she must have the 9th year of schooling or equivalent and career seniority of three years or more … a vocational training course lasting not less than six months’ (Decree No. 414/99 of 15 October 1999: article 5),Footnote 4 and a professional career was defined with two levels: first-degree and second-degree direct action assistant. In order to be promoted to first-degree direct action assistant, it is necessary to have three years of good and effective service in the second-degree direct action assistant category (Decree No. 414/99 of 15 October 1999). In 2008, the number of years changed to five years.

From the analysis of the regulatory framework, there is a continuity in the tasks required, not just in terms of direct care providing, personal care (hygiene and comfort), health, personal and recreational support, but also equipment and material management (control, storage and distribution of materials and equipment). The cleaning maintenance of private and collective spaces, and even mobility assistance (escorting to medical appointments) remains as an integrated activity within home-based care services. In 2015, the figure of the family assistant resurfaces associated with home-based care services and the responsibility of organising theoretical/practical training courses is attributed to the supporting entity, before the contract signing begins, and training themes have already been defined since the end of the 1980s.

In the period analysed, all the regulation concerning the collective contracts of non-profit social facilities refer, exclusively, to the specification of tasks performed by care assistants, to the career advancement at both degrees and to the remuneration system.

Although there are no significant changes in the legal regulation about the profession, the socio-demographic profile of the Portuguese care worker has changed over the last decades when it comes to numbers, ages, education levels, number of working hours and salary. Between 1995 and 2016, the number of care workers increased almost 1,134.6 per cent (from 1,498 in 1995 to 18,494 in 2016) in care services for older people (Table 1). In these 21 years, the trend of female workers being the majority remained constant and we observe the ageing of the care workers’ group. However, the population revealed more qualifications in 2016 when compared to 1995, when 64 per cent of the population had four years of schooling. In terms of daily work hours, there was also a decrease: 57.7 per cent of the population worked more than 40 hours in 1995 and the average monthly wages had a relative variation of 78 per cent when compared with the national minimum wage (€607 without deductions).Footnote 5

Table 1. Care workers in non-profit residential care in Portugal

Source: Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento (2018).

This general profile of care workers follows the profile identified through the narratives of care workers and their care trajectories. Most of the interviewees had performed other jobs in the past, reported similar professional and personal trajectories, and placement in precarious jobs.

Care trajectory experiences: profiles and patterns

The findings suggest a diversity of care trajectories, revealing not only different motivations and objectives that underpin the decision to choose work in the care sector, but also the personal, family and professional events that shape the initial trajectories. Analysis of narratives revealed differential dynamics, which we classified into three types of trajectories of care (Table 2).

Table 2. Types of trajectories of care work

Domestic labour, low qualification, African immigrants

The majority had four years of schooling, some incomplete (five interviewees). With experience in domestic work, nine interviewees are linked by the same stories of labour precariousness, as cleaning staff.

Women, older, experiences in services or industry jobs, long-term unemployment and family trajectories of care

Long-term unemployment, illness and family issues, and long experiences of taking care of family members in the past, are issues associated with the decision to search for work in the area, perceived as the only alternative for employment. Twenty-five were hired as care workers, of whom only seven revealed having had training upon starting the job.

An example is E32, with 15 years as a receptionist in a company. Unemployment and enrolment in the employment centre provided her with the opportunity to attend a theoretical-practical course (‘geriatric agent’) that allowed her to do an internship at the home where she has worked for 10 years. E9 had the same trajectory. She worked in graphic arts for 20 years, became unemployed and was proposed by the employment centre to attend a geriatric course, where she took the 9th grade equivalency.

Women, younger, Ukraine, Brazilian immigrant, secondary level, dificulties in finding jobs

E36 is 24 years old. She attended a technical course in laboratory chemistry, but she knew that it would be difficult to work in the area and decided to apply to a nursing home. On her own initiative, she took several courses, first aid workshops and medical emergency. She had several references in the family of care-givers (grandparents and aunts) and the interest in care made her discover the care worker profession. E34 had a similar trajectory. He made the 12th grade and had several, but temporary, work experiences in services (from a store employee to an assistant at a dental clinic). His contract was not renewed and he remained unemployed. He also tried to attend a geriatrics course through the employment centre but in vain, there were no vacancies for people with 12th grade. Because of his long experience taking care of his grandmother, he decided to work in the area of care work.

Despite the diversity of individual, familiar and professional trajectories, care work includes, for all the interviewees, a set of activities that concern the wellbeing and comfort of the residents, as well as responding to basic needs, and personal and health care:

In the morning, there is the bathing, the beds and hygiene … at night we do rounds, diaper changing. (E1)

Beyond care work itself (the bathing, the hygiene, the food, among others), it is necessary to record information:

We have to register the basic needs of each resident and each one of us needs to record this information. (E4)

These record-keeping activities happen in just two of the homes.Footnote 6 In some nursing homes, it is necessary to provide domestic work, cleaning, washing, grooming and helping out in the kitchen; this is mainly carried out by the first type of less-qualified care worker (E16, E15). In opposition, some of the interviewees, mostly from the second and third types, also perform the role of intermediary co-ordination, supervision and training of the newest members (E2, E3, E10, E27, E36).

The job description of care work is also based on an important social stratification shaped by unequal starting conditions: age, qualification, race, immigration status. Regardless of professional trajectories, there are some elements that are transversal to the interviewees; the interpretation that they make about the factors that contribute to the quality of care and the relationship they establish with the residents, sometimes strong reasons that contribute to not leaving care work.

Determinants of care quality

From the interviewees, we created a typology of determinants that influence the quality of care provision (Figure 1). The first dimension is related to the lack of qualified staff and working conditions: work overload, lack of social recognition of profession, staff ratio deficit, shift rotation, low wages. The high incidence of work-related poor health, due to physical and emotional burnout, have consequences on early retirement and the high turnover of care workers, factors that explain the organisational conflict, associated also with the lack of internal communication and group cohesion, leadership and technical supervision. Staffing ratios are not compatible with the health status of the resident population, a population with severe care needs (cognitive and physical impairments), who suffer mainly from dementia. These multiple factors have impact on the care model: collectivisation of care, tasks routinisation, time pressure, non-person-centred care and increasing ‘the risk of an institutionalised culture of care omission’ (Gil, Reference Gil2018: 552).

Lack of qualified staff

One of the main problems identified is ‘the lack of qualified staff and the lack of professional recognition’ that hampers the task of hiring adequate human resources to the profession. Very demanding recruitment processes are incompatible with the limited offer that exists in the labour market and the requirements of the profession. Low-skilled, unemployed women, sometimes with no experience in the care sector, is the first profile type that appears in the labour market.

The first problem identified by interviewees is working in rotating shifts. Between shifts, there is also a gradation. The morning shifts are considered the ‘hardest’ and ‘exhausting’, the ‘heaviest’ because they concentrate a higher number of tasks:

It's making the beds, getting them ready, get the clothes in the laundry. It's a lot of work, and sometimes we leave tasks for the night-shift, for example restocking. (E29)

E17 describes the morning shifts as ‘more complicated, physically’ while the night shifts are ‘psychologically harder. They are tired, more agitated and they want to go to bed’.

Insufficient staffing and long working hours are reasons identified by interviewees to explain the workload. E32 does on average 10–12 hours daily:

Today I arrived at 6 am and I won't leave at 4 pm, but at 6 pm. I will fetch the materials for the shift and if there are doctor's appointments, I have to organise them. I always do a lot more hours than what I am paid for. (E32)

Usually we are four. If there's four of us, I'll do seven residents. If there's three I'll do nine residents, for 30 people. With four care workers we can work well. I started at 8 am and we end at noon. (E25)

Inadequate ratios do not allow a stable schedule:

we can't get schedules, having all those elements on the team. This ends up overloading the ones that are on duty and we have to speed up. (E28)

The uncertainty facing the number of care workers available on a daily basis is described by E4 as ‘working on the tightrope’.

Physical and mental exhaustion

From the total of interviewees, 27 consider that care work has effects on their physical health and 12 on their mental health. Health problems, already diagnosed by health services, make up the main life impacts of these care workers: ‘arthrosis, tendinitis, back pain’ and mentally ‘psychologically speaking, it's quite gruelling’ (E2).

E20 considers that to be able to work she needs antidepressants on a daily basis:

Psychological exhaustion, a lot of fatigue. There was one day where four people calling for me. I stopped and screamed: Stop! Which way do I go? I can't take it. I devoted myself greatly and today I'm suffering the consequences for it. Z. there's no paper, Z. there's no towels, where are the soaps, Z. the towels, since I'm the oldest and I've been here the longest, I have access to everything and its always Z. I reach a point where I don't want to be Z. I reach a point of exhaustion that I have to call in sick! (E20)

Despite an annual medical examination being mandatory, according to the health legislation, hygiene and safety at work legislation, this means a generic exam (electrocardiogram, hearing) and mental health is totally neglected (‘mental assessment doesn't exist’ (E17)(Gil, Reference Gil2018).

Impacts on the physical and mental health of care workers are the main reasons for absenteeism, early retirement and high turnover.

Organisational conflict

Staff shortages and workload pressures, lack of team co-operation, absence of leadership, low wages and alternating shifts make care work an unappealing profession and people end up leaving the sector. This perspective is shared by the majority of the interviewees. One of the consequences of hard-working conditions is organisational conflict. The lack of social and institutional recognition of care work leads to conflicts inside the teams, and also among the professionals, staff and managers. The problem is the lack of communication within the institution (E23): ‘In my opinion the problem is communication.’ For E36 and E10, younger care workers, lack of communication is transversal to the hierarchical chain, influencing the entire organisational system:

I think there is lack of training, because when I entered in the first nursing home, I didn't know anything; I was learning from colleagues and not always is what the colleagues teach us is the right thing to do. I think there is a lack of training and dialogue, above all, among care workers, managers and residents. (E36)

Given this scenario, it is important to question in what way the organisational climate reflects itself in the care practices. The lack of co-operation between the various team members, the weight and the non-co-operation of the older person are some factors that interfere in care practices and are reasons to trigger interpersonal conflicts.

To E5, the worst aspect of care work is the weight of the older people (‘heavy people, with no mobility, are a dead-weight’). The ‘physical strength’ necessary on a daily basis is also seen as the hardest aspect for E18 (‘We get completely beat, then you've got the hernias, the spine’). E18 considers that for people not to fall, the weight and physical strength used can lead to incorrect positioning. E16, for example, explains the excessive weight being due to the quality of nutrition. An unhealthy nutrition regime with little physical exercise and a sedentary lifestyle run the risk of obesity.

Health status of residents

The physical and mental impairments of the residents, due to biological ageing, the loss of identity, dealing with dementia and the consequential spatial and temporal disorientation, are also identified as, individual determinants of residents, one of the main difficulties felt by those who provide care.

To E17 it is witnessing the physical and mental decline on a daily basis:

It's very sad, I tell you. Those that have been here for a long time, seeing them is very sad. Seeing what they were and what they are now! (E17)

The physical and mental decline is associated with advanced age, 80, 90 years with signs of dementia. To E14, it is dealing with death and mourning: ‘It's hard physically and mentally, but I'll be honest … is dealing with death…’ ‘About mourning, no one talks about it’, considers E8. Dealing with death on a daily basis appears to be the hardest part of care work for 11 of the interviewees.

It is important to question in what way the organisational, interpersonal and individual determinants reflect themselves in the care practices and what is meant by decent and indecent care.

(In)Decent care: outputs of care quality

According to the interviews, decent care is associated with care individualisation, a set of tasks, including day-to-day activities, such as feeding, bathing and basic health treatment. E27, while defining decent care, emphasises the respect for the person's individuality and the fulfilment of their needs:

We have to respect their way of being and we respect each and every one of them, their skills and their personality, their experiences and when they arrive, they still want to do what they always did. We don't oppose them. They like to get dressed and undressed by themselves, combing their hair. For some of them, we are worried they might fall down so we follow-up on their hygiene, their getting dressed or their diet. Check if they eat or not, if they drink water are some examples of good care. (E27)

Decent care also implies a relational dimension. The need for interaction and communication (‘to have a chat with’ (E4); ‘Listen to them, their life stories’ (E36); ‘for me some [older person] are family’ (E16)).

However, staff shortages and workload pressures not only the limited time available to spend with each person but also to meet basic needs adequately, including minimum standards of personal care, considered as good care practices. The lack of time and inadequate personnel ratios do not allow for extra activities (simply chatting, walking exercises or collaborating on occupational activities) other than what is institutionally established. The limited time with residents, sometimes, generates feelings of frustration and overload:

They need other types of care that we can't provide … we have to follow the rules, the schedules, the plan. They have to eat and take their medication. It is very intense! Walking exercises, keeping them occupied, it is necessary but we don't have the staff for that and we can't do it ourselves. (E3)

E18 also considers that the lack of staff has inevitable impacts on the older people and reflects on the quality of care:

People need time, and in the end, we transmit a certain aggressiveness. It's not being aggressive! It's just abruptness, it's turning this way, turning that way. Things are done a bit abruptly. (E18)

Poor care practices aggravate when the accumulation of tasks coincides with team conflict and when the care is performed by only one care worker. The weight, the non-co-operation of the older person and the lack of co-operation between the various team members increase the risk of abruptness and inadequate movement. One example of autonomy loss has to do with personal care related with hygiene needs: ‘making them use diapers without it being necessary to avoid supporting the WC’ or ‘making them wait to go to the toilet intentionally’ or ‘making the elderly wait on purpose’ are examples of neglectful care and ways of (un)care that promote dependency.

The use of physical containment, as a safety measure to prevent falls, is a normalised practice and accepted institutionally:

E29: Our main worry is them falling. So, they wear the belts and it's the fear of them trying to get up and falling over. The people have the belts, and we go to the bathroom with them, and then they have to return.

Interviewer: Are they restrained in the morning and afternoon?

E29: Yes, because of the falls. It's our main issue. Ms X can walk and I really don't like having her restrained to a wheelchair. We don't have a care worker for each one! Now, for example, we are all busy and they follow us and we are afraid they might fall down given their age.

The use of physical containment and omissions in care are justified by the hard-working conditions and workload (‘Interferes with us and will interfere with the way we deal with them’ (E35)). Physical efforts and mental exhaustion lead, sometimes, to sudden gestures and inadequate responses to an older person.

Requalification of the care worker profession: a challenge for LTC

For interviewees, job quality depends on more selective recruitment processes, the certificate training process, better wages, a healthier work environment (prevention of work accidents, physical and mental burnout), continuous performance assessment and career prospects.

Specifically, E32 believes that the ‘vocational training’ she attended for six months should be mandatory on top of on-the-job training (‘To have a licence to work in the care sector’), ‘vocational training’ should be continuous (E5) and E37 added that any sort of training should not be in conflict with long working hours. Additionally, selection should happen through a defined recruitment process (E38), compatible with a skills profile for the profession (E12, E36), and the skills profile and training have to be adequate for the needs of dementia (E36, E32).

A selective recruitment process ‘that makes all the difference. Liking what you are doing’ (E1), associated with a caring profile, is essential to requalify the profession. Care work implies interpersonal competences (the empathic ability to listen to the other person and knowing how to communicate), person activities (washing, helping with feeding), but also specialised care. Sometimes, care workers are involved in health care: the administration of medication, under the supervision of nursing, maintaining care records and care plans.

Discussion

Demographic changes and the increase in working women in society has led to the so-called ‘caring gap’. This phenomenon raises a central issue for LTC policy: who will care for the elderly? The labour involved in providing care is feminised and typically undervalued, whether informal or formal, and marginal groups in society (women, long-term unemployed people, immigrants) who face discrimination in the workforce tend to become care workers (Tronto, Reference Tronto2010; Rummery and Fine, Reference Rummery and Fine2012).

In Europe, despite the significant investments in work–life balance measures for workers (Bouget et al., Reference Bouget, Spasova and Vanhercke2016) and the professionalisation of care workers (OECD, 2020), the effect of those policies on the gendered division and segregation of labour involved in providing care is unclear. Additionally, the low level of care-givers’ allowance income ends up not valuing and not compensating for the care provided, enhancing risks such as early exit from the labour market or a greater dependence on other family members.

Rummery and Fine (Reference Rummery and Fine2012: 337) pointed out that poorly resourced carers, and poorly resourced care recipients, have far fewer choices and fewer options to ‘exit’ care relationships and choose other arrangements. It is a double process of exclusion, caring for a family member for a long period, without public support, and, at the same time, the care sector emerges, as a potential employment area, for all care-givers who left the labour market to care for a family member and who want later return to work. This exclusion reflects the secondary status of care in society and the social devaluation of care work. Moreover, this leads to a higher risk of precariousness and in-work poverty (Eurofound, 2017). Therefore, it is important to look at the dynamic intersection of informal and formal, and the undervaluation of care work (paid and unpaid) also leads to precarious working conditions in care sectors.

The use of mixed methods allows me to portrait the profile of Portuguese care workers, which is represented mostly by middle-aged women, with low qualifications (median 45 years in 2016; median 37 years in 1995) (Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento, 2018). While in 1995 the percentage of care workers under 25 was 12.8 per cent, in 2016 it dropped to 3.2 per cent, which indicates a majority influence of older age groups, a tendency also identified in OECD countries (Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, Nozal, Mercier and Tjadens2011; OECD, 2020). This trend is also confirmed by the narratives of care workers and their care trajectories.

Portugal, like other Mediterranean countries, is characterised by strongly familialistic care regimes, where women continue to play a central role in family care, and poor regulation of professional care work with impact on unmet labour needs in the care sector (Salis, Reference Salis2014).

The majority of informal care is provided daily by women over 50 (OECD, 2019a), a trend which mirrors the care workers’ profile (middle-aged women, with low qualifications). Care trajectories allowed me to illustrate the diversity of lifecourse patterns of care which are determined by cumulative social inequalities (gender, age, labour status, race and immigration status). The interviews revealed long work histories within the care sector, showing family experiences in caring, work instability, difficult working conditions (poorly paid, overtime, rotating shifts, few break times), without promotions and career development perspectives, as well as high levels of sick leave and regular absences.

Precarious working conditions seem to be a common denominator which connect different trajectories of care, including women who decide to leave their jobs to take care of family members and go back to work after many years. After a long period of unemployment, the reintegration of these care-givers into the labour market is difficult because of their age, lack of social protection and low level of education: that is why the care sector represents one of the areas with the greatest employability.

Informal care also includes the invisible work carried out by domestic workers, mainly by immigrants, predominately female live-in care workers, who play a crucial role in providing care in family households and in the care sector, as cleaning staff. The inequalities of gender, age, race, nationality and immigration status are embedded in care labour and in the migration trajectories of care workers (Wall and Nunes, Reference Wall and Nunes2010; Abrantes, Reference Abrantes2012; ILO, 2019).

This tendency is also confirmed by Hussein (Reference Hussein2010), who highlighted that the low prevalence of internal promotions and career development points to a low level of continuing professional development among older workers. The lack of recognition of care work is part of a social system that gives low value to the care (informal and formal) of older people (Hussein, Reference Hussein2018) and the still lacking recognition of care work as skilled work (Salis, Reference Salis2014).

The Portuguese care workforce is often associated with low recognition and salaries, which leads to relatively high staff turnover and staff shortages with impact on complying to the legally defined ratio, but in practice a seven to nine residents ratio, representing an indicator of large workloads (Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, Nozal, Mercier and Tjadens2011). On the other hand, the population in nursing homes is increasingly dependent. Physical and mental impairments of the residents, dealing with dementia and obesity, are also identified as, individual determinants of residents, one of the main difficulties felt by those who provide care.

Care is performed by care workers, sometimes alone, and for long periods; health problems (physical and mental) become motives for sick leave, constituting another determinant with serious impacts on care workers and quality of care. The OECD (2020) suggests that shift work, and cases of intensive caring and workload, are associated with health problems such as anxiety, burnout and depressive symptoms, reducing the ability to care and to remain in the care sector.

These results raise an inevitable issue: is it possible to provide a decent quality of care service in this context? For interviewees, decent care is associated with care individualisation, a set of tasks, including day-to-day activities, and a relational dimension, dignity and respect. Although caring relationships involving reciprocal emotional investment are an important outcome of care (Rodrigues, Reference Rodrigues2020), sometimes, it is a central factor that dampens the decision to leave the profession.

Personal dedication and motivation are minimised in the case of care workers with long experience in caring or who have professional training. The social disqualification that exists around care in society has repercussions on the organisational culture, in which the fragmentation of professional practices (in the health and social fields) prevails and, sometimes, there is a lack of internal communication, an organisational climate of conflicts allied to difficult working conditions, all of which have a toll on quality care practices. In summary, lack of qualified staff, physical and mental health problems, organisational conflicts and the dependence of residents are the determinants that most influence quality care.

Abrupt movements, screaming, ignoring, the type of language used (childish or slang), diaper usage, leaving people bedridden for long hours by themselves and without care, physical containment to prevent falls and work overload, and the excessive weight due to a diet rich in carbohydrates and lack of movement and physical exercise, are some indicators that surface from the interviews, which are considered as abusive acts in institutions (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Biggs, Tinker, Stevens and Lee2009; Drennan et al., Reference Drennan, Lafferty, Treacy, Fealy, Phelan, Lyons and Hall2012; Melchiorre et al., Reference Melchiorre, Penhale and Lamura2014). Some of these practices are identified in daily institutional life and recognised by interviewees as inadequate care, however, they are justified because of staff shortages, insufficient skills and poor job quality.

Although the Portuguese care worker profile has changed over the last decade, there is no investment to improve working conditions and competences, and there is no national strategy to attract younger generations to join the care-working sector. There is a regulation about the need for training skills, but in practice there is no public control over the exercise of the care work, or care workers’ skills, training and profile.

The analysis showed that the Portuguese legislation has stopped in time and there have been no significant changes in the requalification of the profession. However, there have been remarkable pressures and efforts to enhance the professionalisation and qualification of care work in recent years (although with differences) in Europe (Spencer et al., Reference Spencer, Martin, Bourgeault and O'Shea2010; Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, Nozal, Mercier and Tjadens2011; Salis, Reference Salis2014; ILO, 2019; OECD, 2020). There are proposals to assist care workers, such as the role of technologies in care (monitoring and remote care, alarms and safety) (Gil et al., Reference Gil, Moniz and São-José2019) and marketing campaigns promoting the profession (Hussein et al., Reference Hussein, Manthorpe and Stevens2011; OECD, 2020).

Regulation of care services and the qualifications of the care workers, training (geriatric care, care management, communication and use of technology) and registration of care workers are some of the major ways in which governments have tried to raise the quality of care (Cangiano and Shutes, Reference Cangiano and Shutes2010; ILO, 2019; OECD, 2020).

A European strategy for care-givers (informal and formal) is needed to guarantee that care work is recognised, valued and supported, facilitating the collaboration between formal and unpaid carers and promoting adequate social protection and job quality, essential conditions to ensure decent care. Therefore, it is important to identify what are the policies that promote dignified care and support tasks for those who care, paid and unpaid care work, reducing gender, professional and social inequalities.

Resorting to immigrants to face the growing needs of the care sector has been approached by several studies in last decade, which has allowed the importance of taking into account the role of more open immigration policies to be highlighted (Mackenzie and Forde, Reference Mackenzie and Forde2009; Cangiano and Shutes, Reference Cangiano and Shutes2010; Colombo et al., Reference Colombo, Nozal, Mercier and Tjadens2011; Hussein and Manthorpe, Reference Hussein and Manthorpe2012; Hussein et al., Reference Hussein, Stevens and Manthorpe2013; Salis, Reference Salis2014).

Professionalisation, mandatory and on-the-job training, selected recruitment processes, better working conditions, continuous performance assessment and attractive career plans were some of the policy recommendations discussed in order to reinforce social recognition of care work and, thus, to respond to the growing demand for care. The high demand for social care, due to the ageing of the population (Eurostat, 2019; Gil, Reference Gil2020), calls for continued efforts in improving working conditions, and a national strategy which promotes the recruitment of a diverse, younger and more-qualified workforce is needed – measures that will have impact on the long-term quality of care provided.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia) in Portugal (grant number SFRH/BPD/107722/2015).

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.