Introduction

Disasters pose a serious threat to older adults’ health, safety and wellbeing. Roughly 71 per cent of people who died in Louisiana in the United States of America (USA) as a result of Hurricane Katrina were over age 60, most of whom died in their homes and communities (Gibson, Reference Gibson2006). Similarly, the Chicago 1995 heatwave disproportionately impacted community-dwelling older adults, especially those experiencing poverty and social isolation (Klinenberg, Reference Klinenberg2015). In addition to increased mortality risk, disasters negatively impact older adults’ health by exacerbating chronic health conditions, creating psychological strain, and disrupting access to care and social services (Aldrich and Benson, Reference Aldrich and Benson2008; Sakauye et al., Reference Sakauye, Streim, Kennedy, Kirwin, Llorente, Schultz and Srinivasan2009; Malik et al., Reference Malik, Lee, Doran, Grudzen, Worthing, Portelli, Goldfrank and Smith2018).

As 15 per cent of the US population is currently over age 65, a number expected to grow to nearly 25 per cent of the population by 2060 (Administration for Community Living, 2018), and disasters become more frequent and severe in a changing climate, the development and implementation of strategies to improve the disaster resilience of older adults is an increasingly urgent public health priority (Gamble et al., Reference Gamble, Hurley, Schultz, Jaglom, Krishnan and Harris2012). The concept of community disaster resilience includes a focus on the needs of vulnerable populations such as older adults, and emphasises the role of governmental, non-governmental and community-based organisations in providing social services and assistance to provide vital community needs each day and after a crisis (Wulff et al., Reference Wulff, Donato and Lurie2015). Research and policy efforts specifically focused on older adults’ disaster resilience are also growing, although a stronger research agenda is necessary to address this age group's disproportionate disaster outcomes (Hartog, Reference Hartog2014; Brockie and Miller, Reference Brockie and Miller2017; Kwan and Walsh, Reference Kwan and Walsh2017; Liddell and Ferreira, Reference Liddell and Ferreira2019).

Nearly 80 per cent of adults age 50 and older want to remain in their communities and homes as they age, or ‘age-in-place’ (Binette and Vasold, Reference Binette and Vasold2018). There is increasing interest in the USA and globally in identifying effective strategies that enable older adults to age-in-place (Vasunilashorn et al., Reference Vasunilashorn, Steinman, Liebig and Pynoos2012; Scharlach, Reference Scharlach2017). In recent years, a growing number of initiatives and organisational models have been implemented across the country to create ‘age-friendly communities’ with social and physical environments to support older adults ageing-in-place (Greenfield, Reference Greenfield2012; Lehning et al., Reference Lehning, Scharlach and Wolf2012; Scharlach, Reference Scharlach2012; Siegler et al., Reference Siegler, Lama, Knight, Laureano and Reid2015). Two of the most prominent ageing-in-place organisational models are senior centres and Villages. Senior centres are one of the most widely used services among the USA's older adults ageing-in-place, providing recreational, nutritional, health and social service programmes at nearly 11,000 centres nationwide (Pardasani and Thompson, Reference Pardasani and Thompson2010; National Council on Aging, 2015). Villages are an increasingly popular volunteer-based and ‘grassroots’ organisational model that co-ordinates a diversity of services and programmes to promote health and quality of life for older adults ageing-in-place (Scharlach et al., Reference Scharlach, Graham and Lehning2012).

Community-based organisations are increasingly recognised as critical partners in local disaster management (Chandra et al., Reference Chandra, Williams, Plough, Stayton, Wells, Horta and Tang2013; Ritchie et al., Reference Ritchie, Tierney, Gilbert, Miller and Rivera2010; Drennan and Morrissey, Reference Drennan and Morrissey2019; Shih et al., Reference Shih, Acosta, Chen, Carbone, Xenakis, Adamson and Chandra2018; Sledge and Thomas, Reference Sledge and Thomas2019). However, there has been little research examining the role of community-based organisations that support older adults ageing-in-place in building disaster resilience. A recent RAND Health report examined perspectives of public health departments, Village and age-friendly community leaders on disaster preparedness and found that many Villages are engaged in programmes directly relevant to disaster preparedness, but noted a lack of guidance regarding effective strategies for Villages and other ageing-in-place organisations to play an effective role in disaster preparedness for their members (Shih et al., Reference Shih, Acosta, Chen, Carbone, Xenakis, Adamson and Chandra2018). Similarly, though senior centres reportedly conduct some disaster-related programming (Ashida et al., Reference Ashida, Robinson, Gay and Ramirez2016), there has been no in-depth examination of the senior centre role in supporting older adults’ disaster resilience.

Conceptual model

A prominent theoretical framework in disaster resilience scholarship discusses six ‘levers of resilience’ as means of strengthening community resilience to disasters. The model points to ‘wellness’, or health promotion and population health, ‘access’, or availability and quality of health and social services, ‘education’, or disaster-related communications, ‘engagement’, or participatory decision-making in disaster planning, response and recovery, ‘self-sufficiency’, or community responsibility for disaster preparedness, and ‘partnership’, or collaboration between government and non-governmental organisations on disaster-related activities (Chandra et al., Reference Chandra, Williams, Plough, Stayton, Wells, Horta and Tang2013). The World Health Organization's Global Network of Age-friendly Cities and Communities ‘domains of livability’ identifies eight key areas that influence the quality of life of older adults ageing-in-place. These community features include (a) outdoor spaces and buildings; (b) transportation; (c) housing; (d) social participation; (e) respect and social inclusion; (f) civic participation and employment; (g) communication and information; and (h) community support and health services (World Health Organization, 2007). This research operationalises a conceptual model integrating key elements from ‘levers of resilience’ and ‘domains of livability’ frameworks to examine the type and nature of resilience-building activities supported by ageing-in-place organisations. Thus, this study contributes to the literature by investigating the applicability of this conceptual model to examine the disaster resilience-building activities that King County, Washington senior centres and Villages currently support, and the challenges and opportunities these organisations face in building disaster resilience for older adults ageing-in-place.

Case study description

King County, Washington is a county in western Washington State with a population of over two million (US Census Bureau, 2018). Earthquakes, severe weather, winter weather, floods, landslides and wildfires are priority hazards for King County (King County Office of Emergency Management, 2015). Seventeen per cent of the population is age 60 and older, and the 60+ population will near 25 per cent of the total population by 2040. Among residents age 65 and older, 19 per cent speak a language other than English at home and 3 per cent do not speak any English (Aging and Disability Services, 2017). A diversity of organisations across King County, including 35 senior centres and five Villages, offer activities and services for older adults to support ageing-in-place (Aging and Disability Services, 2017; Village to Village Network, 2019). King County, Washington was selected as a case study because of its rich network of ageing-in-place organisations and its relatively high urban–rural, socio-economic, and racial and ethnic diversity (Public Health – Seattle & King County, 2016; Aging and Disability Services, 2017).

Methods

Study design

Semi-structured interviews were conducted between August and October 2018 with individuals in leadership roles in senior centres and Villages in King County, Washington. We chose a qualitative study design to gain a rich contextual understanding of respondents’ perspectives on the subject of ageing-in-place organisations’ role in building older adults’ disaster resilience. Study procedures were determined to qualify for exempt status by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division on 25 July 2018 (Category 2).

Participant recruitment

Eligible study participants were in a leadership role at the time of the study, either as a staff member or board member, at a not-for-profit organisation whose primary function is to provide services to community-dwelling adults age 65+ in King County, Washington. Eligible participants were sampled purposively to represent diversity in organisation size, geographic location and structure.

The sample was sized to attain saturation of themes, meaning that subsequent interviews would no longer provide new themes or insights (Fusch and Ness, Reference Fusch and Ness2015). Twenty-eight organisations were invited to participate in the study through email and phone outreach using contact information available through community partner organisations and through online directories of senior centres and Villages located in King County (Aging and Disability Services, 2016; Village to Village Network, 2019). Of the 28 organisations that were contacted, 14 agreed to participate in an interview. This was sufficient to achieve saturation. Of the non-respondents, ten failed to respond to multiple contact attempts; two expressed interest in participating in an interview but did not have the capacity to participate in an interview during the study time period; two indicated that their organisation was not involved in disaster-related activities.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted in person or by phone after respondents provided informed consent to participate. One author (CP) with masters-level training in qualitative research methods conducted all interviews. A semi-structured interview guide with open-ended prompts and follow-up questions was developed a priori based on the study's conceptual model to solicit information on ageing-in-place organisations’ activities related to key ‘domains of livability’ and ‘levers of resilience’. The interview guide included questions on respondents’ perspectives on disaster-related risks, organisational activities related to disaster resilience, and challenges and opportunities to increasing older adults’ disaster resilience. Examples of questions include: ‘How does your organisation's work support members in preparing for, responding to or recovering from disasters?’, ‘How might disasters threaten your organisation's operations and members?’, ‘Do you currently partner with any other organisations to support disaster preparedness for your centre's members?’ and ‘In an ideal world, what do you think the role of [senior centres or Villages] in promoting disaster resilience would be?’ (see Appendix 1). Two authors developed the interview guide (CP and NE) and two authors reviewed and provided feedback on the guide (BB and AB). Three practitioners, including two local and county government staff and one senior centre director, none of whom were interviewed for this study, also reviewed and provided feedback on the guide. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Demographic information on organisational size, location and structure was collected from study respondents and from organisation websites.

Data analysis

We chose to use the ‘framework approach’ to conduct a thematic analysis of the data (Pope et al., Reference Pope, Ziebland and Mays2000). We first familiarised ourselves with the data through review of audio-recordings and transcripts to list key ideas and recurrent themes. We then developed a preliminary codebook through inductive and deductive approaches (Braun and Clark, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Codes were identified a priori based on the research questions and the study's conceptual model (Elo and Kyngäs, Reference Elo and Kyngäs2008) and additional codes were created for concepts that recurred in the data (Pope et al., Reference Pope, Ziebland and Mays2000). NVivo qualitative data analysis software (QSR International version 12, 2018) was utilised to index the data by applying the codes to the transcripts. Two transcripts were double-coded by (CP) and a researcher outside the study to increase the validity and reliability of code description and application. A consensus-building approach was utilised to adjudicate minor discrepancies, and modifications to the codebook were made as appropriate (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Thompson and Williams1997) (see Appendix 2). One researcher (CP) then independently coded the remaining 12 transcripts. Analytic memos were developed by interview, by code and by theme to summarise major themes that emerged. ‘Member checking’ was conducted by sending respondents a summary of key points after the interview to increase the validity of subsequent findings (Yin, Reference Yin2011). Coded data were arranged and synthesised by connecting codes to broader themes organised in a thematic framework (Pope et al., Reference Pope, Ziebland and Mays2000). Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic characteristics collected, including services available, organisational structure and size of municipality.

Respondent characteristics

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 15 individuals in leadership roles representing 14 different ageing-in-place organisations. In one case, the individual initially contacted for an interview requested that one additional individual be included in the interview. Table 1 presents the job titles of respondents.

Table 1. Participating individuals by job title

Interviews lasted between 27 and 74 minutes. Respondents had been in their roles for time periods between less than one year and more than 30 years. Given their leadership roles within ageing-in-place organisations, respondents each provided insights on their personal perspectives regarding the role of ageing-in-place organisations in supporting older adults’ disaster resilience, as well as on their own organisation's past and present involvement in disaster-related activities. Organisations represented included government senior centres, non-profit senior centres and Villages, and were located in cities and towns with populations ranging from less than 10,000 to greater than 500,000 (Public Health – Seattle & King County, 2016). Organisations served between roughly 200 and 3,500 individuals yearly and provided a variety of social services and programming to older adults ageing-in-place (Table 2).

Table 2. Ageing-in-place organisation demographics

Results

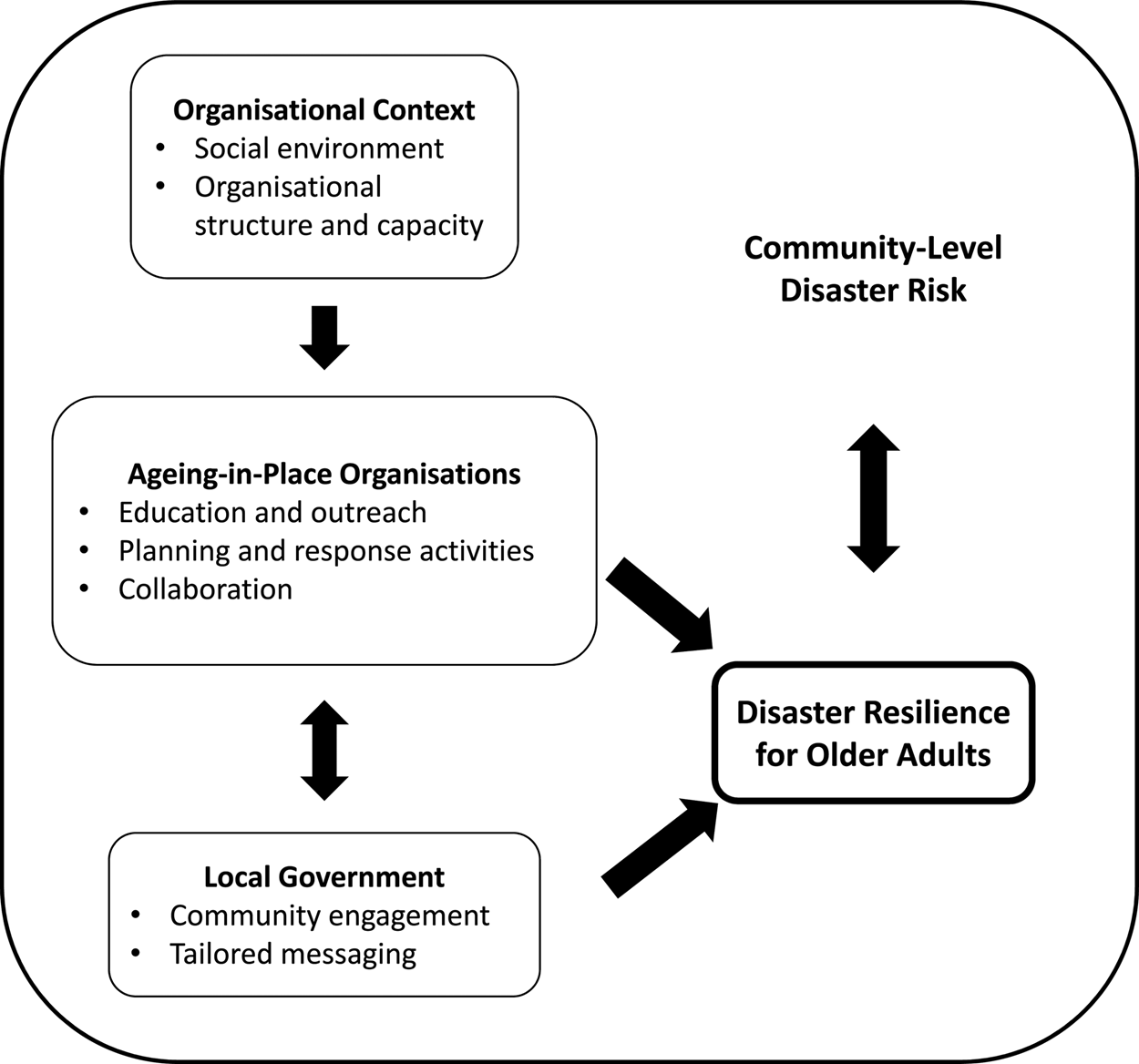

Our analysis generated four major themes that influenced older adults’ disaster resilience: community-level disaster risk, organisational context, ageing-in-place organisation actions and government responsibilities (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Major thematic categories found to influence ageing-in-place organisations’ participation in disaster resilience activities.

Community-level disaster risk

Respondents expressed concern around a wide range of hazards posing threats to their organisation's operations and its members, including wildfire smoke, extreme heat, snow, flooding, pandemic flu and earthquakes. Hazards that occurred frequently could be forecast, and those that caused minimal infrastructure damage were perceived as less dangerous and more manageable than rare and unpredictable hazards that would cause region-wide damage. Respondents expressed the greatest concern for seismic risks, given the region's vulnerability, the scale and severity of damage that could occur to buildings and transportation infrastructure, and the lack of feasible guidance for earthquake preparedness and response strategies for older adults. Several respondents also expressed concern that climate change would worsen disaster-related risks.

Respondents felt that older adults are at risk in a disaster due to limited access to medication, power outages limiting use of electricity-dependent medical equipment, infrastructure damage preventing building evacuation or limiting transportation options, weather conditions increasing fall risks and limited social services causing increased social isolation. Sources of increased vulnerability identified by respondents included very advanced age, limited mobility or frailty, social isolation, low income, homelessness, chronic medical conditions including mental illness, limited access to digital communication and limited English proficiency/prior immigration status. Many respondents described having an informal understanding of which members were especially vulnerable and may need additional support in a disaster situation. However, they also emphasised that ageing-in-place organisations do not serve every older adult in their community, and their disaster-related activities may not reach older adults who are socially isolated or homebound and especially vulnerable to disasters. However, several respondents also emphasised that while older adults may experience greater vulnerability to disasters, they are also strong, savvy and resilient; as one respondent said:

Overall, knowing this cohort, this age group, they're a pretty resilient group of people, and they're going to do as well as anybody because they have lived through a lot. And they know what to do to get through and get by. (P7, government senior centre)

Organisational context

Respondents pointed to local contextual factors, including social environments and organisational structure and capacity, as influential for ageing-in-place organisation's capacity to support older adults’ disaster resilience.

Social environments

Respondents described rural–urban differences in organisational capacity to support disaster-resilience activities, noting that urban communities had less social isolation and more services available to support disaster response, including transportation, health care and first responders. However, respondents from smaller cities and towns (populations under 100,000) described close community connections in rural areas as an asset to their organisations in providing flexible and appropriate services to support members in disaster situations. As one respondent explained:

The good news about a small town is that people know each other and it's about relationships, right? So I've got the mayor's cell phone number on my cell phone. And if something's really going wrong or whatever, I could be like, ‘Hey, I need help. Who do I talk to? How can we get this done?’ (P3, non-profit senior centre)

Many respondents felt that the social connections created through ageing-in-place organisations would reduce older adults’ disaster-related risks by connecting older adults with organisation staff, volunteers and members who could provide support in a personal emergency or a disaster situation. One respondent described their organisation as ‘an extension of family for many, many people’ (P1, government senior centre). Respondents noted that these social networks enabled older adults who were members or volunteers of ageing-in-place organisations to both provide and receive support in preparing for, responding to or recovering from disasters. However, several respondents felt that groups of community members, rather than ageing-in-place organisations, should play a lead role in disaster planning, given the uncertainty that staff would be present or that the facility would be accessible in a disaster situation. As one respondent explained:

I feel like it has to be a neighbourhood response, and yes, I do need to be involved, because if it did happen while I'm here, I would be part of the neighbourhood right at that moment, but I don't think the lead can be us. (P9, non-profit senior centre)

Organisational structure and capacity

While respondents recognised disasters as a risk to older adults’ health and wellbeing, their organisations’ ability to reduce disaster risk effectively for older adults reflected the realities of their organisational structure and the capacity of their physical facility and staff. Government-run senior centres, non-profit senior centres and Villages each identified unique strengths and weaknesses in their capacity to support older adults’ disaster resilience. Government senior centres described co-ordination, training opportunities and resources from local emergency management departments as an asset, though most government senior centres described few opportunities to provide input on disaster plans or take part in disaster-related activities without being directed to do so by emergency management staff. Non-profit senior centres described greater autonomy in developing and implementing disaster-related plans and programmes, but they referenced restrictive grant conditions and limited funds and staff capacity as barriers to supporting resilience-building plans and activities. Villages pointed to their organisations’ large volunteer base who are equipped to provide in-home services as advantageous for providing disaster-related support in older adults’ homes (e.g. storing water, installing air conditioning units). One respondent described the potential for volunteer networks to provide support in a disaster event, saying:

Our volunteers are helpful and considerate people because that's what brought them to here. So I would imagine that if there's a disaster, they're going to be thinking about their family and themselves first, but then as soon as they have the capacity to, ‘Oh, I know there's a Village member a few houses down. I'm going to go check on them’. (P14, Village)

Leaders of organisations whose mission focused on serving older adults from specific ethnic and linguistic groups anticipated that their strong community ties and in-depth understanding of the unique social services needs of their members would benefit their clients on an everyday basis and especially in a disaster. One respondent described their organisation as uniquely equipped to co-ordinate with government partners on emergency planning and to provide a centralised location for their community to access resources and information in a disaster situation.

Respondents saw their organisation's physical facility and staff as influential to their organisation's capacity to support disaster resilience. While some organisations had their own building, most operated in community centres or shared a building with other organisations; those that shared a space anticipated collaborating with their neighbouring organisations on disaster planning and response. Most organisations’ facilities were not seismically retrofitted, and several respondents felt their facility would be unsafe to access in a disaster, precluding participation in disaster response activities. Respondents also discussed the need for adequate staff capacity and expertise to support disaster-related activities. Many respondents emphasised that staff passion for the organisation's mission of serving older adults motivated them to ensure members’ needs were met on an everyday basis, and that this commitment to providing support would continue in a disaster situation. As one respondent explained:

I think it's part of the philosophy of this senior centre. And we are here to serve seniors. And certainly, we're here to serve them most when they're without electricity or closed in because of snow. (P10, government senior centre)

Ageing-in-place organisation actions

Respondents discussed education and outreach, planning and response activities, and collaborations as potential actions for ageing-in-place organisations to support older adults’ disaster resilience (Table 3).

Table 3. Disaster-related activities currently supported or expected to be supported by ageing-in-place organisations

Education and outreach

All respondents pointed to provision of disaster preparedness information or resources as an appropriate role for ageing-in-place organisations in supporting older adults’ disaster resilience. Government senior centres, non-profit senior centres and Villages all described similar levels of past and ongoing involvement in disaster-related communication activities. Each organisational model perceived themselves as a trusted source of information for their members and felt they were well-positioned to disseminate disaster preparedness guidelines specifically for older adults. Education and wellness programming are strong components of existing programming for ageing-in-place organisations, so respondents saw incorporating disaster-related education and outreach into their work as highly feasible. Many described a range of disaster risk communication activities, including seasonal messaging around weather-related hazards, posting and disseminating materials from state and local public health departments and emergency management departments, hosting disaster preparedness educational events, and answering questions and providing information on an individual basis. Several respondents discussed low attendance at previous disaster preparedness educational programmes they had hosted. They noted that disaster preparedness information offered by ageing-in-place organisations may not reach all members of the organisation, but rather those who were already concerned about disaster risks and motivated to seek out resources and support. Respondents emphasised the importance of delivering disaster preparedness information in a format appropriate for an older adult audience; in-person delivery of large-font, hard-copy materials were preferred over online communication. As one respondent explained:

It probably also requires sort of boots on the ground and go and talk to people about this stuff. If it's on a website, it's just the fact that it's not going to get to everybody. Seniors necessarily aren't as savvy. (P12, non-profit senior centre)

Respondents also encouraged positively framing disaster preparedness messages and ensuring messages come from a trusted messenger, such as ageing-in-place organisation staff, volunteers or other members. Several respondents described peer-to-peer educational programming in which older adult members or volunteers provide formal or informal information on disaster preparedness or response as an especially effective communications strategy.

The lack of appropriate disaster messages tailored specifically for an older adult audience was frequently discussed as a challenge; respondents especially emphasised a need for more appropriate messages for older adults with limited mobility, chronic health conditions, limited financial resources or homeless older adults, as standard preparedness recommendations were not actionable for those groups. While respondents felt that disaster preparedness materials were readily available in appropriate translations, they emphasised that building bi-directional relationships, cultural understanding and trust were also critical to effective disaster risk communication for diverse communities. As one respondent said:

The websites that have all this information, they put a lot of information online in every language possible. They try to be culturally responsive. But it's online, and it doesn't necessarily connect people. So your job's not done after you do that. It's like you have to be out there in the community. You have to be talking to seniors. You need culturally responsive right there in the community, people who speak the language. (P12, non-profit senior centre)

Planning and response activities

Nearly all respondents had a disaster or emergency plan in place, though the detail and formality of plans varied widely between organisations. Government senior centres were more likely to have detailed and formalised disaster plans, while the scope and formality of planning varied widely for non-profit senior centres. Villages described less formal planning around disaster-related activities, expressing a more informal expectation that, if feasible, Village staff and volunteers may provide support to member needs as they arose during or after a disaster event. Many respondents described plans specifically outlining procedures for their organisation to evacuate the building, or policies around organisational closures during unsafe weather conditions. Especially sophisticated examples of disaster plans included a disaster recovery plan outlining mutual aid agreements, a disaster communication plan providing tailored messages for different audiences to ensure staff was consistent in its messaging, and hazard-specific plans including protocols for both the organisational response and educational programming for members. Several respondents pointed to the uncertainties around the type, severity, and timing of a disaster as barriers to effective planning, emphasising the need for flexibility in disaster planning and response. Respondents frequently referenced the challenge of allocating staff time to the development and maintenance of disaster-related plans. As one respondent put it:

That's why these things need constant review, and revision, and updating and the reality is nobody has the time and the energy to establish any of that. (P9, non-profit senior centre)

Similarly, while many respondents discussed staff training in first aid, CPR, and the US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and American Red Cross (ARC) trainings as valuable, maintaining a trained staff was challenging as staff turned over.

Many organisations served as designated ‘warming centres’ or ‘cooling centres’ in extreme temperatures, but respondents described relatively low attendance during hot weather in spite of efforts to make cooling centres inviting by providing refreshments and entertainment. Most government senior centres’ facilities were designated as an ARC shelter site, and respondents described providing support to ARC volunteers who were unfamiliar with the facility. Respondents emphasised the importance of considering pets when considering older adults’ disaster preparedness and response needs, and several described incorporating pets into their organisation's cooling centre and sheltering policies.

Many respondents saw maintaining a list or registry of older adults in need of additional support in a disaster as unfeasible; however, several described adding home meal delivery recipients to lists maintained by local fire and police departments to direct first responders to homebound older adults. While many respondents would not have the capacity to reach out to members in the event of a disaster, a few described co-ordinating or conducting home visits or wellness checks during disaster events. These efforts by staff and volunteers included checking in by phone, shovelling driveways, installing air conditioners and co-ordinating pharmacy visits as in-home supports provided by organisational staff and volunteers.

Collaborations

Respondents discussed collaborations as essential to their organisation's involvement in disaster-related activities. Many felt that partnering with local emergency management departments or the ARC was essential, given these organisations’ expertise in disaster preparedness and ageing-in-place organisations’ limited capacity to develop new programmes; as one respondent described, ‘we are constantly doing cross-programming with them so that we can get the information out of whatever needs to be out’ (P2, government senior centre). Other collaborators discussed food banks, neighbourhood ‘hub’ disaster volunteer groups, home care agencies and religious organisations. Respondents described experiencing challenges in co-ordinating disaster planning with other community organisations due to staff and volunteer turnover. Urban organisations generally described fewer disaster-related collaborations than organisations in smaller communities. A respondent discussed the collaborations that had occurred in a previous disaster, saying:

In our community, because we're small enough, because we've been here a long time, I have other city departments that call and say, ‘We can't do this and that today, so what can we do to help you?’ (P10, government senior centre)

Ageing-in-place organisations shared insights and disaster planning materials with one another through personal connections and through a state-wide association of senior centres. However, some respondents saw little need for collaboration with other ageing-in-place organisations around disaster activities, but they felt that neighbourhood-scale co-ordination between organisations was necessary; as one said:

seems like that's what would be needed in a disaster. You don't need a centralised something … because nobody could get to it. You would need to work with all the little partners that were inside trying to help serve people in a disaster. (P6, non-profit senior centre)

Government responsibilities

Respondents looked to local government agencies and organisations to co-ordinate inclusive disaster planning and tailor disaster communications and policies specifically for an older adult audience. Many respondents also emphasised a desire for two-way collaborations with government emergency management planners. They expressed an interest in ageing-in-place organisations having the opportunity to participate in disaster planning conversations to share their insight on older adults’ specific needs and identify opportunities for their organisation to contribute to disaster preparedness and response. A respondent shared:

I just think that whether it be the state or the county or cities, when they have disaster planning committees or meetings, to be sure and involve your senior centres. Because we are the focal point within the community. We know the seniors. (P10, government senior centre)

While some respondents felt they were not equipped to contribute significantly to disaster response efforts, others felt that their organisation had both physical resources and social connections that would be valuable in a disaster situation and should be included in government-led neighbourhood and city-level disaster plans. As one respondent put it:

If there's a loose way that we would be connected to a bigger overall emergency response in the city, we would be glad to do that. But I can't plan what that would be. I would need somebody who is looking at the bigger picture to just talk to me about how we could fit in and help. (P6, non-profit senior centre)

Respondents looked to government agencies and organisations to take a hands-on approach to developing educational materials and providing organisational policy recommendations that specifically addressed the heightened vulnerability and unique needs of older adults. As one respondent emphasised:

We really need the local government to be here physically and tell us exactly how we can make this work together, collaborate with each other, and make sure that we are prepared … And I say this because our constituents are different. They're not the school-age children. These are very vulnerable, and there should be a different programme for that. (P5, non-profit senior centre)

Discussion

Our results indicate that ageing-in-place organisations support a diversity of activities that may build older adults’ disaster resilience. Respondents described supporting activities that aligned closely with concepts in the study's conceptual model, supporting both the ‘levers of resilience’ and ‘domains of livability’ frameworks and suggesting that ageing-in-place organisations support healthy ageing on an everyday basis and contribute to older adults’ disaster resilience. Our analysis suggests that local physical and social contexts influence the role ageing-in-place organisations play in supporting older adults’ disaster resilience. Organisations saw their diverse approaches to supporting older adults’ disaster preparedness, response and recovery as complementary and closely connected to local government disaster planning and response activities.

Our research highlights the importance of considering local context when considering an organisation's capacity to support disaster-related activities, a conclusion which supports the ‘community gerontology’ framework's emphasis on communities as fundamental contexts for ageing research, policy and practice (Greenfield et al., Reference Greenfield, Black, Buffel and Yeh2018). We found that institutional actors such as senior centres and Villages play diverse and influential roles in supporting older adults’ disaster resilience, providing appropriate supports for the disaster-related needs of older adults in a diversity of community contexts even within a single county. Future studies should conduct more in-depth examinations on the influence of diverse social, economic and physical contexts on ageing-in-place organisations’ approach to building older adults’ disaster resilience. Our findings also point to a need for community-engaged disaster planning efforts at the neighbourhood, city and county level to ensure that plans to support vulnerable populations will align with the realities of unique local physical and social contexts. Ageing-in-place organisations have an in-depth knowledge of the detailed realities of serving older adults in their communities; soliciting their input throughout the disaster planning process could ensure that the unique needs of older adults are consistently considered and addressed.

Factors influencing disaster risk and resilience opportunities included both built environment and social environment factors, reflecting multiple domains of the World Health Organization's (2007) ‘domains of livability’ framework. While ageing-in-place organisations recognised that built environment ‘domains’ such as housing, transportation and buildings are relevant to disaster risk and resilience, they felt ill-equipped to support interventions related to modifying built environment factors to support older adults’ disaster resilience. Future studies should therefore examine the perspectives of other organisations, such as senior housing, public transportation and urban planning organisations, in creating built environments that support disaster resilience for older adults. Our findings also support the emphasis in the ‘domains of livability’ framework on the need for a diversity of stakeholders, including individuals, community organisations and policy stakeholders, to address the breadth involved in creating age-friendly communities. Given that ageing-in-place organisations focus primarily on providing social services (aligning with the framework's ‘social environment’ domains of social participation, communication, and community support and health services), future studies may benefit from explicitly focusing in greater depth on the contributions of ageing-in-place organisations to these specific ‘social environment’ domains, both in the context of general community ‘age-friendliness’ and in the context of building older adults’ disaster resilience.

Our findings that education and partnerships were central to ageing-in-place organisations’ disaster activities align closely with these components of the ‘levers of resilience’ framework (Chandra et al., Reference Chandra, Williams, Plough, Stayton, Wells, Horta and Tang2013). Future research should examine the efficacy of specific communication and collaboration-focused activities to build a stronger evidence base for informing ageing-in-place organisations’ disaster-related programming. Respondents recognised that older adults’ disaster resilience was improved by ageing-in-place organisations’ day-to-day work supporting health promotion and providing social services, aligning with the ‘wellness’ and ‘access’ levers described in the framework as well.

Given limited budgets, staff capacity and disaster-related expertise, ageing-in-place organisations must prioritise effective and feasible resilience-building activities. Government agencies and organisations should support and incentivise ageing-in-place organisations’ participation in disaster preparedness educational activities and neighbourhood-scale disaster planning efforts. Ageing-in-place organisations need accessible tools and resources to enable their organisations to make use of their unique assets and identify feasible opportunities to contribute to disaster planning and response. Organisations would benefit from successful examples of ageing-in-place organisations contributing to local disaster activities and supporting older adults in preparing for and responding to disasters.

Leadership from local government agencies and organisations is essential in co-ordinating disaster planning and response for older adults. Providing tailored policy guidance for each ageing-in-place organisational model may be valuable (Shih et al., Reference Shih, Acosta, Chen, Carbone, Xenakis, Adamson and Chandra2018), given the unique challenges and opportunities faced by government senior centres, non-profit senior centres, and Villages. Similarly, ageing-in-place organisations in smaller communities and large urban areas may benefit from tailored support, although more research is needed to understand how best to support older adults’ disaster resilience in rural communities (Ashida et al., Reference Ashida, Robinson, Gay and Ramirez2016). Brief planning documents, draft programme materials and Web-accessible trainings may enable ageing-in-place organisations with limited resources or in rural environments to participate more easily in resilience-building activities. Local and state government agencies and organisations should develop such tools in collaboration with community partners, but they may benefit from existing materials and guidance developed at the federal level (Gibson, Reference Gibson2006; Acosta et al., Reference Acosta, Shih, Chen, Xenakis, Carbone, Burgette and Chandra2018).

Our results show that ageing-in-place organisations play a role in providing community-level supports to older adults ageing-in-place, potentially increasing their resilience to disasters. This research focused specifically on the role of organisational staff and volunteers in supporting older adults’ disaster resilience; it did not seek to examine the contributions members of ageing-in-place organisations make to community resilience, either independently or through their involvement with ageing-in-place organisations. While our findings suggest a need for organisational involvement in disaster-related activities supporting older adults, this does not necessarily support a ‘top-down’ approach to disaster-related activities in which ageing-in-place organisations, rather than older adults themselves, contribute to disaster resilience. Previous studies have found that older adults are often assets in disaster situations, playing key roles in supporting disaster preparedness, response and recovery in their communities (Cornell et al., Reference Cornell, Cusack and Arbon2012; Howard et al., Reference Howard, Blakemore and Bevis2017). Our findings pointed to social support and peer-to-peer communications as ways in which older adults contribute to community resilience through their involvement in ageing-in-place organisations. Future research should explore the perspectives of older adults themselves on if and how ageing-in-place organisations equip them to build their community's disaster resilience (Tuohy et al., Reference Tuohy, Stephens and Johnston2014).

Limitations

The main goal of this qualitative research endeavour is to provide well-grounded rich description rather than objective and population-wide generalisable knowledge; findings may be limited in their relevance to ageing-in-place stakeholders in other settings (Miles and Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994; Morse, Reference Morse1999). This study was conducted in a large county in the Pacific Northwest, and findings are most directly relevant to other large metropolitan areas and areas with similar priority hazards to the study area. However, the King County area contains urban, rural and suburban populations representing diverse populations, and many of the study's findings may be relevant to any community's efforts to build disaster resilience for older adults. This study described ageing-in-place organisation leadership's previous direct experience with disaster response to hazards such as snow, extreme heat, wildfire smoke and minor earthquakes. Respondents also discussed their past and current preparedness activities, as well as hypothetical future disaster scenarios. However, as King County has not experienced a severe disaster event in recent decades, respondents may be limited in their capacity to discuss effectiveness of specific strategies employed in disaster response or recovery. Future research should examine the perspectives of ageing-in-place organisations located in areas that have recently experienced disasters (such as hurricanes, tornadoes or wildfires) to expand on this study's findings on the roles of ageing-in-place organisations in building disaster resilience to diverse hazards.

Respondents volunteered to participate in the study, and the perspectives of organisations that did not elect to participate in the study are not reflected in these results, including organisations with very limited resources or those with no previous involvement in disaster-related activities. Our study population included only senior centres and Villages, and therefore our findings do not represent perspectives from other organisational types, such as age-friendly communities, senior companionship programmes or faith-based organisations, that may also support older adults’ disaster resilience. Future studies should examine the potential disaster resilience-building role of each ageing-in-place organisational model, as well as conducting a more in-depth examination of Villages, as this study's geographic scope resulted in a limited number of Villages in its sample. Interviews were conducted with organisational leadership, whose perspectives may differ those of from other staff, volunteers or organisational members. Our study also focused on organisations that serve a select group of older adults ageing-in-place; older adults who are not connected to senior centres and Villages may be homebound or experiencing severe social isolation, factors that likely put them at great risk in disaster situations; future research should prioritise the identification and evaluation of resilience-building strategies for these high-risk groups.

Conclusion

Given the increasing frequency and severity of disasters and the ageing of the US population, there is an urgent need to identify and implement effective strategies to support older adults in preparing for, responding to and recovering from disasters. Ageing-in-place organisations recognise disasters as a threat to older adults’ health and safety, and see opportunities to contribute to disaster resilience for older adults in their communities, though the type and extent of participation in resilience-building activities reflect each organisation's unique local context. Ageing-in-place organisations have insights and resources to contribute to local disaster planning efforts. They are also uniquely equipped to serve as a trusted messenger of disaster-related information for a highly vulnerable population with specific risk communication needs. Local government agencies and organisations can support ageing-in-place organisations in building older adults’ disaster resilience by including them in neighbourhood and city-level planning conversations and by providing tailored disaster planning and messaging material for older adults and ageing-in-place organisations.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the ageing-in-place organisation leaders who volunteered their time to be interviewed for this study.

Financial support

This work was supported by the University of Washington Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Boeing Focal Award (CP).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix 1: Interview guide

Thank you for agreeing to participate in my study. My thesis is exploring the role of community-based senior service organisations in supporting older adults’ disaster resilience, or a community's capacity to rebound from a disaster. A ‘disaster’ is defined as a situation or event that overwhelms local capacity: a few examples of disasters that have previously been declared in King County are earthquakes, heatwaves, wildfires and severe storms. I am talking with senior centre and Village leadership to (a) gather information on how [senior centres or Villages] in King County think about disasters and (b) identify key recommendations for emergency planning.

The interview will last about one hour. I will be taking notes and recording the interview so that I can refer to the discussion later. We may write up our findings in a report or for publication in a peer-reviewed journal. We will not refer to you by name in any report or publication without your prior explicit permission. We also will share de-identified results with [names].

Your participation in this interview is voluntary. You can refuse to answer any question, and you can leave the study at any time. You will not be penalised for not answering any question or for leaving the study at any time.

If you are interested in reviewing a summary of our conversation, I would be happy to share that with you. Please let me know if that's something you are interested in.

Do you have any questions before we begin?

Do you consent to participate in my study? [Ask for a verbal ‘yes’.]

Question 1: Tell me about how you think a disaster might affect your [senior centre or Village]'s members.

Follow-up: What do you think might happen in a disaster?

Follow-up: Have you dealt with any disasters during your time at the [senior centre or Village]?

Response efficacy

Question 2: What role, if any, do [senior centre or Village] have to play in supporting older adults in preparing for, responding to or recovering from a disaster?

Probe: Does your organisation have a role in response or recovery from a disaster caused by a natural hazard?

Follow-up: What types of support could your organisation offer to its members or the community in a disaster situation?

Follow-up: Are there things that you think your [senior centre or Village] do that would not make a difference?

Self-efficacy

Question 3: How is your [senior centre or Village] equipped to support disaster resilience for older adults?

Probes: Resources, skills, interest, staff knowledge.

Follow-up: What types of efforts or preparations do you think should be in place at your [senior centre or Village] but are beyond your organisation's capacity?

Follow-up: How well prepared do you think your senior centre is should a disaster strike? Do you feel your organisation is ready for a disaster?

Question 4: How does your [senior centre or Village]'s work support members in preparing for, responding to or recovering from disasters?

Follow-up: What opportunities do you see for your [senior centre or Village] to make its operations and its members more resilient to disasters in the future?

Susceptibility

Question 5: How might disasters threaten your organisation's operations and members?

Follow-up: Tell me about the types of disaster that you worry about most.

Probe: Can you tell me anything more about that?

Follow-up: How do you prioritise what hazards to plan for at your organisation? Do you have a process for identifying priority hazards?

Severity

Question 6: What type of disaster do you think would be the most dangerous for your organisation's operations and members?

Probe: Can you tell me more about [whatever they mention]?

Probe: Specifics on wildfire smoke, extreme heat, severe weather, earthquakes.

Follow-up: Which of your members do you think would be at greatest risk?

Question 7: In a disaster, what would determine whether your [senior centre or Village] could continue to operate?

Follow-up: How might a disaster impact your operations?

Question 8: Does your [senior centre or Village] communicate with its members about disasters?

Probe: Answering personal questions? Providing written resources? Hosting events or trainings?

Probe: What is challenging about disaster communication? What support would be needed?

Question 9: Does your [senior centre or Village] co-ordinate or provide transportation services?

Follow-up: Would it be feasible for your senior centre to provide transportation support or evacuation support?

Probe: What would be challenging? What support would be needed?

Question 10: Would keeping a list of those in need of language or mobility assistance in a disaster be feasible for your organisation?

Follow-up: What type of information would you be able to record about members in need of assistance?

Question 11: Do you currently partner with any other organisations to support disaster preparedness for your centre's members?

Follow-up: What kind of help would you expect from other organisations or entities in this kind of an event?

Question 12: Does your organisation serve as a cooling centre or a warming centre?

Follow-up (if yes): Can you tell me about that experience?

Probe: Any challenges? Did you receive resources or support? Did members or non-members attend?

Question 13: Do you know if your [senior centre or Village] building would be able to withstand an earthquake?

Question 14: In an ideal world, what do you think the role of [senior centres or Villages] in promoting disaster resilience would be?

Question 15: How do you think your senior centre compares to other senior centres in King County in terms of resources and capacity to address disasters?

Follow-up: What do you think underlies differences between centres in regards to disaster preparedness? Does your centre get the same amount of support from government programmes compared with other senior centres? How about financial resources?

Question 16: Do you have any suggestions for how city and government programmes working to support disaster preparedness for older adults could better support your members?

Demographic questions

Question 17: How long have you worked at [name]?

Question 18: How many members does your [senior centre or Village] serve?

Question 19: What neighbourhood(s) do most of your members live in?

Question 20: We are interested in the living situation of your members. Of all your members, what percentage do you think live alone, with family, in a retirement community, are homeless, or other?

Question 21: We would also like to know about the financial situation of your members. Of all your members, what percentage do you think are lower-income, middle-income and upper-income?

Question 22: Is there anything else you would like to tell me that might be important to this project on the topic of disaster resilience?

Snowball sampling

Question 23: Are there other [senior centre or Village] directors that you recommend I talk to?

Appendix 2: Codebook