Introduction

Concerns over the economic implications of the ageing population are growing. Nowadays in Belgium, 16 per cent of older persons (⩾65 years old) report having significant mobility difficulties, while around 29 per cent report experiencing difficulties in performing at least one daily activity (Van der Heyden and Charafeddine, Reference Van der Heyden and Charafeddine2014). In 2013, 8.4 per cent of elderly persons received residential care in Belgium (Vrijens et al., Reference Vrijens, Renard, Camberlin, Desomer, Dubois, Jonckheer, Van den Heede, Van de Voorde, Warkiers, Léonard and Meeus2016), while in the four neighbouring countries the rate varied between 4.1 and 5.6 per cent (OECD, 2016). Overall in Belgium, 4.9 per cent of older persons received long-term nursing home care in 2013 (Vrijens et al., Reference Vrijens, Renard, Camberlin, Desomer, Dubois, Jonckheer, Van den Heede, Van de Voorde, Warkiers, Léonard and Meeus2016). With increases in longevity, the absolute number of disabled older persons is expected to rise, leading to increases in long-term care expenditures (Spillman and Lubitz, Reference Spillman and Lubitz2000). In order to keep these expenditures under control, it is believed that promotion and development of community-based support is a sustainable solution compared to institutional care. Estimating the cost of support currently provided to disabled older persons is therefore a crucial initial step to evaluate the potential economic consequences of community support systems. To our knowledge, there has been no large-scale study published on the cost of support of community-dwelling disabled older persons in Belgium. Moreover, most of the international studies were limited to the estimation of additional costs borne by disabled persons in comparison with non-disabled persons (Wilkinson-Meyers et al., Reference Wilkinson-Meyers, Brown, McNeill, Patston, Dylan and Baker2010; Morciano et al., Reference Morciano, Hancock and Pudney2015; Antón et al., Reference Antón, Braña and de Bustillo2016; Hirsch and Hill, Reference Hirsch and Hill2016) or on specific diseases, such as dementia (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Schenkman, Zhou and Sloan2001; Jonsson et al., Reference Jonsson, Jonhagen, Kilander, Soininen, Hallikainen, Waldemar, Nygaard, Andreasen, Winblad and Wimo2006; Suh et al., Reference Suh, Knapp and Kang2006; Jönsson and Wimo, Reference Jönsson and Wimo2009; Gustavsson et al., Reference Gustavsson, Jonsson, Rapp, Reynish, Ousset, Andrieu, Cantet, Winblad, Vellas and Wimo2010, Reference Gustavsson, Cattelin and Jonsson2011; Quentin et al., Reference Quentin, Riedel-Heller, Luppa, Rudolph and König2010; Schwarzkopf et al., Reference Schwarzkopf, Menn, Kunz, Holle, Lauterberg, Marx, Mehlig, Wunder, Leidl, Donath and Graessel2011; Wimo et al., Reference Wimo, Jönsson, Gustavsson, McDaid, Ersek, Georges, Gulacsi, Karpati, Kenigsberg and Valtonen2011; Gerves et al., Reference Gerves, Chauvin and Bellanger2014).

In Belgium, the role of the state is to provide universal access to long-term care services by predominantly financing various ‘benefits in-kind’. Long-term healthcare services for persons living at home (e.g. nursing, medical home care and paramedical) are financed at the national level through the federal compulsory health insurance system (the National Institute of Health and Disability Insurance (NIHDI)) covering 99 per cent of the population (OECD, 2017). Its funding is mainly based on social security contributions (from workers, employers and retirees) and also general taxes (Willemé et al., Reference Willemé, Geerts, Cantillon, Mussche, Costa-Font and Courbage2011: 300). The driving principles for access to healthcare services are equal access and freedom of choice. The payment system is mainly based on fee-for-services.

Support for at-home living services, mostly financed by taxes, are regulated at regional levels and organised locally to help persons in need with their instrumental activities of daily living (IADL; e.g. domestic tasks) and with personal care. The aim is to prioritise the support of persons with the highest levels of need and with low income. A co-payment is requested according to household financial resources. Alongside this system, since 2001 and regardless of functional limitations and income, a system of vouchers is also possible (financed by taxes). It was implemented to reduce significantly the labour costs of workers providing home care services (e.g. housework, meal preparation) or those outside the residence (e.g. shopping, transportation for persons with mobility limitations or other specific chores, such as laundry or ironing). At-home living services using the voucher system are mainly provided by organisations from the private sector.

An intermediary care setting also exists between these home and residential care facilities: day-care centres facilitate the daily support of persons living at home. They provide nursing care and rehabilitation, financed by the regions, alongside user-financed occupational activities and catering. In nursing homes, care provisions are publicly financed based on a case-mix system determined by the disability profiles of residents and the number of healthcare staff (Van den Bosch et al., Reference Van den Bosch, Willemé, Geerts, Breda, Peeters, Van De Sande, Vrijens, Van de Voorde and Stordeur2011). Boarding and lodging costs are financed mainly by residents (or in the case of financial incapacity, by relatives or the public municipal welfare). Finally, in Belgium, seven ‘sickness funds’, representing the political and religious spectrums, also play a significant role in the financing of long-term care services. The sickness funds offer complementary and supplementary insurances to their members for specific health care provisions and home care services. Private insurance may also intervene in the funding of long-term care. To summarise, the support of disabled older persons in Belgium is mainly based on benefits in-kind with a ‘multilevel governance’ (Degavre et al., Reference Degavre, Nyssens, Bode, Breda, Fernandez and Simonazzi2012) involving various organisations from the healthcare and social sectors. Such fragmentation of the long-term care system hinders the centralised management of resources at the microlevel which would allow for routine calculations of long-term care costs. Hence, to fill the knowledge gap in Belgium, we propose estimations based on the cost of resources that support disabled elderly persons at home.

The aim of the study was to estimate the direct costs (medical and non-medical) (Annemans, Reference Annemans2008) of supporting disabled elderly persons in their home. Using a combined perspective, the following stakeholders were considered: public payers (the NIHDI and the regional federated entities), disabled elderly persons and their main informal carers (identified as those helping the older persons most of the time). For formal support, only the cost borne by the NIHDI was distinguished, as no data were available on the shared costs of other funding stakeholders.

The first objective was to estimate costs borne by the different stakeholders (NIHDI, informal carers and other stakeholders) and to identify the main cost components of the following three disability profiles: (a) functional limitations on IADL with low cognitive impairment: IADL (Cogn.); (b) functional limitations on IADL and basic activities of daily living (ADL): Func.; and (c) functional limitations on IADL and ADL with significant cognitive impairment: Func. Cogn. The second objective was to discuss the potential underuse of formal support, by performing a cost benchmarking analysis of various situations at home, defined by the combination of three disability profiles and three presence levels of the main informal carer (none, non-cohabitant, cohabitant). We supposed that these two factors are the main determinants of support at home.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This study was part of a broader research programme (de Almeida Mello et al., Reference de Almeida Mello, Van Durme, Macq and Declercq2012, Reference de Almeida Mello, Declercq, Cès, Van Durme, Van Audenhove and Macq2016; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Cès, Malembaka, Van Durme, Declercq and Macq2019a, Reference Lambert, Legrand, Cès, Van Durme and Macq2019b) aiming to evaluate large-scale innovative bottom-up healthcare projects that support disabled elderly persons at home. Data were collected from 2010 until November 2016. The recruitment criteria were being 60 years of age or older and fulfilling one of the following scoring criteria: a score on the Edmonton Frail scale of at least 6 (total score from 6–7 = ‘vulnerable’ to 12–17 = ‘severe frailty’) (Rolfson et al., Reference Rolfson, Majumdar, Tsuyuki, Tahir and Rockwood2006):

• or at least a Score A – need for assistance to perform personal care (bathing/showering and mobility/toilet use), or additionally with a Score B – incontinence or problems eating, or a Score C – all of these difficulties, assessed by a home-adapted Katz Index (Katz et al., Reference Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson and Jaffe1963) or assessed by the residential-adapted Katz Index, Scores A, B or C (similar to the home version but considering additional criteria regarding disorientation in time and space) or Score D (dementia diagnostic);

• or having been diagnosed with dementia by a geriatrician, neurologist or psychiatrist (in the absence of a score on the residential-adapted Katz Index).

The baseline data used reflected the ‘usual care’ situation. Trained healthcare or social care professionals collected the data through interviews with disabled elderly persons and their main informal carers at home.

The InterRAI Home Care instrument (interRAI HC) and an ad hoc questionnaire (for social care service utilisation and time spent by informal carers) were used. The interRAI HC instrument is an internationally validated and comprehensive geriatric assessment that provides a holistic evaluation of the main components of disability.

In addition, administrative data on the reimbursed healthcare consumption, routinely recorded, were used (individually matched with their Belgian national number between the two databases). For the municipality of the disabled older persons in our sample, the median fiscal income per household and municipality was available (from StatBel, for the year 2013) and used as a proxy for socio-economic status. Low-income municipalities were identified as the first quartile municipalities with the lowest median fiscal income per household, by using a representative sample of the older population in Belgium (provided by the national healthcare intermutualist agency).

Stratification of the sample into different disability profiles

Disability profiles of older persons reflect the levels of long-term care needs and thus the level of support required. Disability is defined as ‘difficulty or dependency in carrying out activities essential to independent living, including essential roles, tasks needed for self-care and living independently in a home, and desired activities important for one's quality of life’ (Fried et al., Reference Fried, Ferrucci, Darer, Williamson and Anderson2004: 255). To characterise degrees and types of disability, functional limitations on IADL and ADL, cognitive impairment (Salvador-Carulla and Gasca, Reference Salvador-Carulla and Gasca2010) and behavioural problems were considered. Indeed, persons with cognitive impairment are more likely to have a higher need of overall supervision due to their cognitive decline (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Maslow and Zhang1999). Furthermore, they are less likely to receive help with IADL and ADL because of possible denial of their disability (Lavoie, Reference Lavoie2000) or are less willing to be helped (Drennan et al., Reference Drennan, Cole and Iliffe2011). Only data with fully completed questionnaires on the variables of interest were included in the study. The Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Performance Scale (IADLP), the Activities of Daily Living Hierarchy Scale (ADLH) (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Fries and Morris1999), the Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Fries, Mehr, Hawes, Phillips, Mor and Lipsitz1994; Hartmaier et al., Reference Hartmaier, Sloane, Guess, Koch, Mitchell and Phillips1995) and the number of behavioural problems (inappropriate sexual behaviour, wandering, verbally aggressive, physically violent behaviour and inappropriate social behaviour) are the components used in the InterRAI HC to determine the disability profiles.

A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted, enabling explanatory variables to be on a unified scale (the scores of the following four scales measuring: functional limitations on IADL, ADL, cognitive performances and the number of behavioural problems) (Hastie et al., Reference Hastie, Tibshirani and Friedman2009). A clustering analysis was performed based on the PCA correlation matrix. A hierarchical algorithm (Ward algorithm) was used to define the number of groups; this is a compromise between having similar individuals within a group, and having groups with important differences (Hastie et al., Reference Hastie, Tibshirani and Friedman2009), computed using the R package FactoMineR (Le et al., Reference Le, Josse and Husson2008).

Disability profiles were described by the mean score compared to the scale cut-off. The cut-off is considered to be the threshold above which disability is significant: 3 (scale range 0–6) for the ADLH, 3 (scale range 0–6) for the CPS, 24 (scale range 0–48) for IADLP and more than 0 (scale range 0–5) behavioural problems.

Stratification into presence levels of the informal carer

Formal and informal care are known to be highly interrelated (Bolin et al., Reference Bolin, Lindgren and Lundborg2008; Bonsang, Reference Bonsang2009; Balia and Brau, Reference Balia and Brau2014). Litwin and Attias-Donfut (Reference Litwin and Attias-Donfut2009) showed that formal support utilisation depends on the family relationship of the main informal carer (spouses, children). Individual situations between spouses and children differ greatly on many characteristics: age, physical ability to help, time schedule constraints, potential other caring responsibilities, ability to choose to get involved in the care of relatives, to delegate or to share tasks, motivations, their ability to cope with unexpected events or difficulties, etc. Also for specific tasks such as intimate care, the willingness to provide help may also be significantly influenced by family relationship, such as gender considerations for children for parent intimate care (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Coon and Crogan2007). The living arrangements of the main informal carer are another important factor, since co-residence with the care recipient fosters the provision of help and overall a high level of involvement of informal carers (De Koker, Reference De Koker2009). Moreover, defining informal care also requires the distinction between non-cohabitant and cohabitant (Cès et al., Reference Cès, de Almeida Mello, Macq, Van Durme, Declercq and Schmitz2017a). Hence, we chose the living arrangements of the main informal carer as the second main determinant of the support. ‘No carer’ was the third complementary modality, besides non-cohabitant and cohabitant. In addition, we did not expect an important discrepancy as mainly children are non-cohabitant and spouses are cohabitant. For children, becoming cohabitant may sometimes be decided after the loss of independence of older persons, for practical convenience. Nevertheless, such a configuration is assumed to remain marginal due to practical constraints (space, location, etc.) and possible financial incentives to live alone.

The various home situations were defined by crossing the three disability profiles of the care recipient with the three presence levels of the informal carer (N = nine sub-groups).

Confidence intervals (CI) were based on bootstrapping using bias-corrected and accelerated method (5,000 replications of the same size as the original sample) (DiCiccio and Efron, Reference DiCiccio and Efron1996; Elliott and Payne, Reference Elliott and Payne2005). In our study, several sub-samples of different sizes were created. Using a normal-based method is not appropriate for sub-samples of small size, given the underlying non-normal distribution of cost data. Hence, we chose to apply the bootstrap method for all sub-samples, regardless of the sample size, thus accounting for positive skew and heavy tails. The analysis was performed in the R boot package (Canty, Reference Canty2017). The estimations of CI of cost differences were performed in Stata SE 15.0 using a generalised linear model with a Gamma family distribution (appropriate for continuous, positive and skewed variables with variance being proportional to the square of the mean) and log link (the log function of the mean of the dependent variable is a linear combination of independent variables) (Mihaylova et al., Reference Mihaylova, Briggs, O'Hagan and Thompson2011).

Cost estimates of formal and informal support

A micro-costing method was used to collect data (Frick, Reference Frick2009; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Rutten, van Ineveld, Redekop and Hakkaart-van Roijen2009). In addition to informal care costs, the costs of formal support used were presented as follows:

• ADL–IADL: nursing care (provided by a registered nurse), domestic help service, home care worker (domestic help and personal care) and meals-on-wheels.

• Equipment (hearing aids, glasses, orthoses, etc.) and incontinence material (a yearly lump sum financed by NIHDI: €493.1 for disabled persons or €160.9 in 2016 for non-disabled persons and, additionally, a minimum monthly cost estimate of €100 for incontinence material, for three pads per day for the persons with incontinence problems at least once per day for urine and/or faeces).

• Health monitoring: personal alarm system, ‘care attendant’ (a healthcare professional monitoring the health status at home); and medical care, including general practitioner and specialists (neurologist, neuropsychiatrists, psychiatrists, geriatrician).

• In-community respite services: day care (including reimbursed transportation costs) and short stays in a nursing home (less than 90 consecutive days).

The average costs per month, in euro (2016), were based on the consumption for the six-month period before baseline.

In the ad hoc questionnaire, the intensity of informal care was measured retrospectively using time spent on care-giving over the past week, and included the following tasks: ADL (personal hygiene care, incontinence management, eating, dressing, use of the toilet and mobility within the house), IADL (meal preparation, medication, shopping, phone use, transportation, use of stairs and finance management) and supervision. For cohabitant informal carers, public commodities were excluded from the time measurement (shopping, household chores, finance management and meal preparation) (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Brouwer and Koopmanschap2004; Cès et al., Reference Cès, de Almeida Mello, Macq, Van Durme, Declercq and Schmitz2017a). The time spent by informal carers was valued using the replacement cost method (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Brouwer and Koopmanschap2004, Reference van den Berg, Brouwer, van Exel, Koopmanschap, van den Bos and Rutten2006; Paraponaris et al., Reference Paraponaris, Davin and Verger2012; Wubker et al., Reference Wubker, Zwakhalen, Challis, Suhonen, Karlsson, Zabalegui, Soto, Saks and Sauerland2014). The valuation is performed according to the unit cost of the closest professional substitute. This estimation can be interpreted as the cost of supporting disabled elderly persons at home in the absence of informal carers. The hourly rate was the cost of home care services (for domestic tasks only or a home care worker), partially subsidised by the regions through a system of vouchers, €22.04 in 2016 (Schooreel and Valsamis, Reference Schooreel and Valsamis2017). Time spent on caring was limited to 17 hours per day for several reasons (Quentin et al., Reference Quentin, Riedel-Heller, Luppa, Rudolph and König2010): some cohabitant carers reported that a high intensity of help was required. However, time use is less identifiable when sharing the same household, particularly when the patient has a high level of need of assistance, as supervision time may actually include being on-call ‘in case of need’ (e.g. 24 hours per day help was a recurrent answer). Furthermore, the daily capacity of carers to provide help (including supervision) is limited, as informal carers also have to perform their own basic ADL and IADL and need to sleep. We performed a sensitivity analysis of the cost estimates of informal care by using two methods: the opportunity cost method (OCM) and the contingent valuation method (CVM). The valuation principle of the OCM is to consider the costs of alternative activities that cannot be performed due to time spent on providing care. The value of the forgone activities is determined by the wages of informal carers, which is consistent with the theoretical analysis of labour supply (Posnett and Jan, Reference Posnett and Jan1996; Chari et al., Reference Chari, Engberg, Ray and Mehrotra2015). We used the net average wage rate (€16 per hour in 2015) for persons both employed and unemployed (Statbel, 2017). For unemployed persons under the age of 65, the minimum net wage rate of €9.5 per hour in 2016 (Eurostat, 2017) was used as a lower bound for reservation wages (Posnett and Jan, Reference Posnett and Jan1996; van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Brouwer, van Exel, Koopmanschap, van den Bos and Rutten2006). Since no information was available on their qualifications, it gives an approximation of their reservation wage. Finally, for persons over the age of 65, we considered opportunity costs to be not null. We used net retirement income (€11 per hour in 2016) as an estimation of the displacement value of leisure activities and/or unpaid labour (Defeyt, Reference Defeyt2017; ENEO, 2017). Furthermore, another scenario can be presented using the CVM; we used the value determined in the De Meijer study (€11.9, adjusted for 2016) that corresponds to the Willingness To Accept (WTA) to provide one additional hour of care (de Meijer et al., Reference de Meijer, Brouwer, Koopmanschap, van den Berg and van Exel2010). The WTA method is based on the assumption that an additional hour of care would require financial compensation since marginal costs are supposed to exceed marginal benefits. The value would represent the net difference between additional benefits and costs (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Brouwer, van Exel and Koopmanschap2005).

For social care services, ‘care attendants’ (a skilled professional who monitors health status at home), services providing domestic help and home care workers (providing domestic help and basic hygiene care), the total number of hours worked over the past week was reported by respondents. The unit cost of the ‘care attendant’ was €30 an hour, as a skilled professional (average hourly rate of nurse estimated in the pilot innovative healthcare projects). For meals-on-wheels, the frequency of meals per month was collected. The cost unit of meals was estimated by phone survey of a sample of organisations providing this service in Wallonia. The real cost is rarely known as there is no separate accounting for such services within organisations. Thus, the estimated unit cost was €6 per meal. A personal alarm system was valued at €55 per month (according to an average of different websites on personal alarm systems).

The accommodation cost of temporary stays in nursing homes, paid by the disabled elderly person, was valued at €45.97 per day (FOD-SPF Economy, 2014). The cost estimation of day-care centres for care recipients has been valued at €15 per day (this cost varies between €10 and 24, according to a sample of day-care centre websites).

The costs of formal support are presented, divided between:

• support funded by the NIHDI, and

• support funded by ‘other stakeholders’ (Others): care recipients, informal carers, regions, sickness funds or private insurances.

Table 1 provides an overview of the different sources of the cost data: the quantity of resources used, cost units of these resources and funding stakeholders.

Table 1. Overview of the data of resources used, cost units and funding stakeholders

Results

Profile of the care recipients and informal carers

The sample consisted of 5,642 disabled older persons, divided into nine sub-groups according to the disability profiles and the presence levels of the informal carer. The individual characteristics of the disabled older persons and their main informal carer are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Profiles of the care recipients and informal carers

Notes: IADL (Cogn.): functional limitations on instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) with low cognitive impairment. Func.: functional limitations on IADL and basic activities of daily living (ADL). Func. Cogn.: functional limitations on IADL and ADL with significant cognitive impairment. CI: confidence interval. Low inc: low-income municipalities. N: total number of disabled older persons.

The three profiles of disability identified had the following characteristics:

• Persons in the group IADL (Cogn.) (N = 1,178) had significant limitations on performing IADL (average score = 32 (range 0–48), compared to the cut-off of 24). The average score of functional limitations in relation to ADL was low (average score = 1 (range 0–6), compared to the cut-off of 3). Finally, cognitive impairment was moderate (average = 2 (range 0–6) on the CPS, compared to the cut-off of 3). The average number of behavioural problems was low (0.2).

• Persons in the group Func. (N = 2,595) had significant difficulties in performing IADL (average score = 34, compared to the cut-off of 24). There were also significant limitations on the ADL (average score = 3, equal to the cut-off of 3), while no cognitive impairment or behavioural problems were reported.

• Persons in the group Func. Cogn. (N = 1,869) had significant difficulties in performing IADL (average score = 42, compared to the cut-off of 24). They also had limitations in terms of the ADL (average score = 3, equal to the cut-off of 3), significant cognitive impairment (average score = 4 on the CPS, compared to the cut-off of 3) and at least one behavioural problem, on average.

The distribution of the presence levels of the informal carer was similar between the first two profiles of disability, without significant cognitive impairment (58% with a non-cohabitant carer, 27% with a cohabitant carer and 16% with no carer). In the group Func. Cogn., the proportion of persons helped by a cohabitant carer was much higher (57%); 38 per cent of persons had a non-cohabitant carer, and only 5 per cent did not have an informal carer. The disability groups were built to be homogeneous. However, within groups, we observed that the average scores in functional limitations and cognitive impairment were higher in the situation with a cohabitant informal carer. The majority of care recipients were females, but within each disability profile, the proportion of females was lower in situations with a cohabitant informal carer (49–58%). The proportion of care recipients living in municipalities with a low median fiscal income per household was lower in situations with an informal carer (6–15%) than without one (26–36%).

The profiles of informal carers were different according to their living arrangements and confirmed our hypothesis on the link between living arrangements and family relationship. Non-cohabitant informal carers were, on average, younger (55 years) than cohabitant informal carers (69 years). Non-cohabitant carers were primarily adult children of the recipient (78–82%), while cohabitants were primarily spouses (74–75%). Overall, the majority of non-cohabitant carers were also helped by at least one other informal carer (49–55%), while cohabitant carers were slightly less often helped by another informal carer (38–42%). The professional activity varied according to the living arrangements of the informal carer. Non-cohabitant carers had, primarily, a professional activity (56–62%), while only 19 per cent of cohabitant carers worked professionally.

The cost of support (per person, per month)

The cost results are presented in Table 3, per disability group and per level of presence of the informal carer. Table 4 shows the differences in the costs of formal support according to the different disability profiles and levels of presence of the informal carer.

Table 3. Average costs of health care and long-term care services used by disabled elderly persons and informal care (per person per month)

Notes: IADL (Cogn.): functional limitations on instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) with low cognitive impairment. Func.: functional limitations on IADL and basic activities of daily living (ADL). Func. Cogn.: functional limitations on IADL and ADL with significant cognitive impairment. CI: confidence interval. NIHDI: National Institute of Health and Disability Insurance. PAS: personal alarm system.

Table 4. Cost differences of formal support between the different profiles of disability and the presence level of informal carers

Notes: Statistics: univariate GLM model, Gamma family, log link. Ninety-five per cent confidence intervals are in parentheses. IADL (Cogn.): functional limitations on instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) with low cognitive impairment. Func.: functional limitations on IADL and basic activities of daily living (ADL). Func. Cogn.: functional limitations on IADL and ADL with significant cognitive impairment. NIHDI: National Institute of Health and Disability Insurance.

In the group IADL (Cogn.), the average total cost of home support was €2,283.6 (95% CI = 2,146.3; 2,454.8), including the cost of informal care. The average cost of informal care was higher in situations with a cohabitant carer, €3,549.4 per month (95% CI = 3,140.6; 3,995) compared with a non-cohabitant carer, €1,064 (95% CI = 965.2; 1,191.1).

The average total cost of formal support was €725 (95% CI = 686.5; 766.9) in this disability group. This cost was significantly lower in situations with a cohabitant carer, €562 (95% CI = 499.4; 639.2) than with a non-cohabitant carer (average difference: −209.1 (95% CI = −297.4; −120.8)) or with no carer (average difference: −271.8 (95% CI = −407.4; −136.1)).

• For the NIHDI, the average total cost was €192.1 (there was no significant difference between the presence levels of the informal carer).

• For other funding stakeholders, the average total cost of formal support was significantly lower in situations with a cohabitant carer, €377.9 (95% CI = 325.6; 442.2) than in situations without one, €598.7 (95% CI = 513.4; 704.9) (average difference: −220.9 (95% CI = 330.1; −111.6)) and in situations with a non-cohabitant carer, €587 (95% CI = 543.6; 638.8) (average difference: −209.19 (95% CI = −283.74; −134.64)). This difference was mainly due to the cost of home care services (domestic help, home care worker, meals-on-wheels) which was lower in situations with a cohabitant carer, €301 (95% CI = 257.8; 352.1) than in the situations without a carer, €523 (95% CI = 444.5; 617.6) or with a non-cohabitant carer, €496 (95% CI = 458.1; 536.9).

In the group Func., the total cost of the home support was €2,738.5 (95% CI = 2,626.4; 2,864.8), including informal care costs. The average cost of informal care was much higher in situations with a cohabitant carer, €4,410.9 (95% CI = 4,109.7; 4,736.5) than with a non-cohabitant carer, €1,050.8 (95% CI = 979.4; 1,134.6).

The average total cost of formal support was €995.5 (95% CI = 960.2; 1,035.7), which was not significantly different between the three presence levels of the informal carer.

• For the NIHDI, the average total cost was €406.7 and varied according to the presence levels of the informal carer. It was significantly higher in situations with a cohabitant informal carer, €548.2 (95% CI = 501.3; 597.9) than in groups with a non-cohabitant carer, €356.6 (95% CI = 335.8; 379.2) (average difference: 191.58 (95% CI = 138.14; 245.03)) and without a carer, €360.2 (95% CI = 318.8; 414.1) (average difference: 188 (95% CI = 119.9; 256.2)).

• For other funding stakeholders, the total average cost was €588.9 (95% CI = 561.9; 619.4) and varied according to the presence levels of the informal carer. It was significantly lower in the group with a cohabitant carer, €453.9 (95% CI = 413.4; 499.7) than in situations with a non-cohabitant carer, €653.5 (95% CI = 616.4; 696.7) (average difference: −199.6 (95% CI = −258.9; −140.3)) and without one, €575 (95% CI = 515.9; 648.3) (average difference: −121.38 (95% CI = −199.8; −43.0)).

In the group Func. Cogn., the total cost of home support was €5,719.7 (95% CI = 5,523.1; 5,928.8) per person per month, including informal care costs.

The average cost of informal care was much higher in situations with a cohabitant carer, €6,311.7 (95% CI = 6,054.3; 6,570.8) than with a non-cohabitant carer, €2,086.6 (95% CI = 1,899.4; 2,283.4).

The average total cost of formal support was €1,343.9 (95% CI = 1,292.9; 1,398.1) but varied significantly according to the presence levels of the informal carer. In situations with a cohabitant carer, the average cost was significantly lower, €1,246.4 (95% CI = 1,181.5; 1,313.2) than in situations with a non-cohabitant carer, €1,506.8 (95% CI = 1,416.3; 1,608.1) (average difference: −260.3 (95% CI = −376.7; −143.9)). Finally, the average cost in situations with a non-cohabitant carer was significantly higher than without one, €1,227.6 (95% CI = 1,071; 1,425.7) (average difference: 279.1 (95% CI = 78.6; 479.6)).

• For the NIHDI, the average total cost was €571.7 (95% CI = 543.7; 601) and no significant differences were observed according to the presence levels of the informal carer.

• For the other funding stakeholders, the average total cost was significantly lower in situations with a cohabitant carer, €648.5 (95% CI = 603.2; 699.5) than with a non-cohabitant carer, €964 (95% CI = 886.6; 1,047.8) (average difference: 315.59 (95% CI = −407.9; −223.3)). The average cost in situations with a non-cohabitant carer was also significantly higher than with no carer, €730 (95% CI = 600; 887.3) (average difference: 233.82 (95% CI = 69.64; 398.01)). The cost of home care services (domestic help, meals-on-wheels and home care workers) was significantly lower with a cohabitant carer, €430 (95% CI = 396.2; 466.8) than in the other two situations, with a non-cohabitant carer, €726 (95% CI = 669.4; 788.2) or with no carer, €624 (95% CI = 506.8; 760.2).

Figure 1 shows the average total monthly costs of support per funding stakeholder. Informal care costs are sub-divided by time: up to eight hours per day and between eight and 17 hours. In the group Func. Cogn., the cost of informal care between eight and 17 hours accounted for 73 per cent of the average total cost of informal care, while in the two other disability groups it was 43 and 52 per cent of the average cost.

Figure 1. Average total costs (per person per month).

Notes: IADL (Cogn.): functional limitations on instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) with low cognitive impairment. Func.: functional limitations on IADL and basic activities of daily living (ADL). Func. Cogn.: functional limitations on IADL and ADL with significant cognitive impairment. NIHDI: National Institute of Health and Disability Insurance.

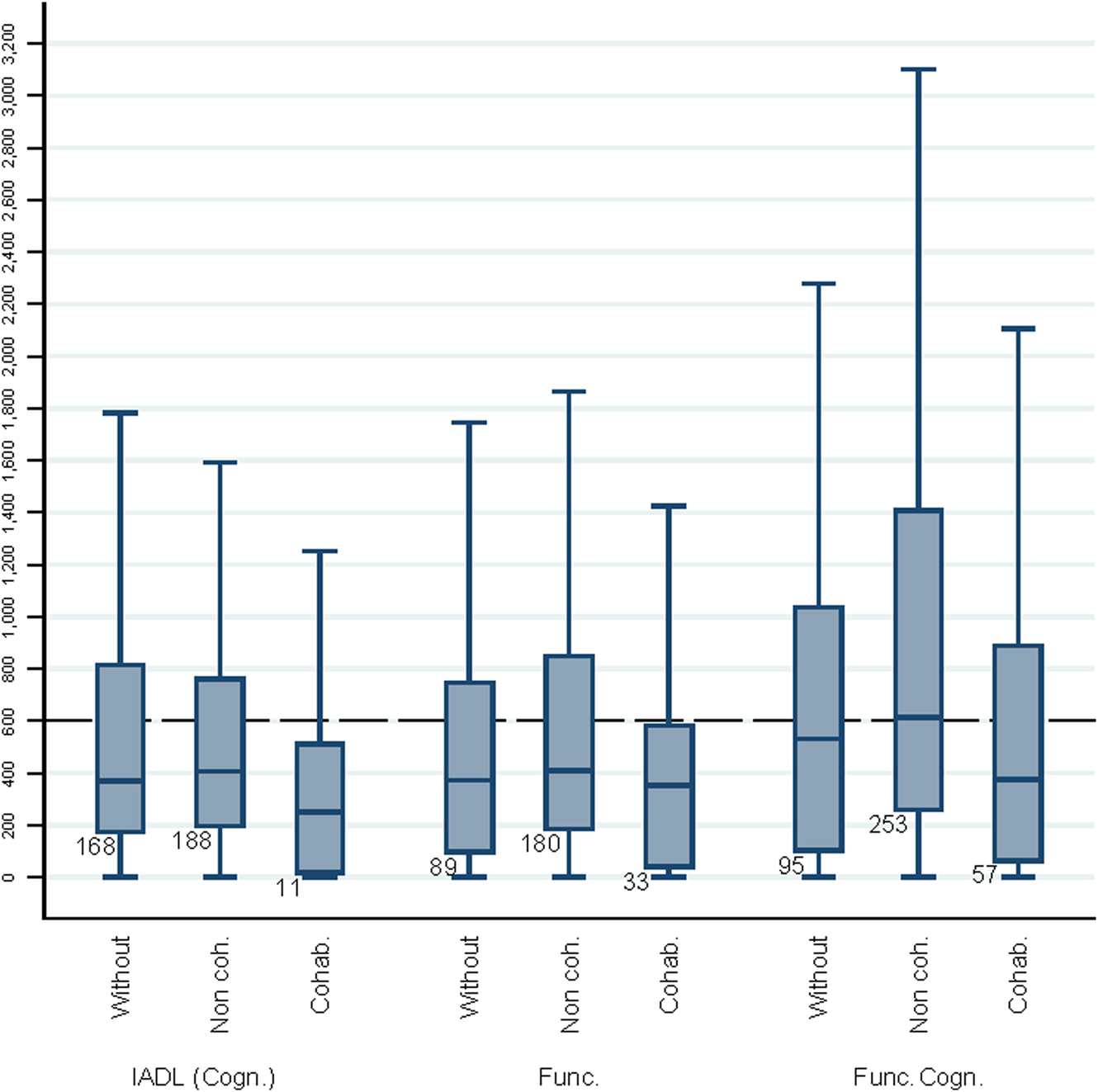

The cost distributions were highly skewed. Thus, box plots, presented in Figures 2–4, were useful to show the overall low levels of use of formal support through the first quartile values and medians, according to the presence levels of an informal carer in the two disability groups with significant functional limitations (with or without cognitive impairment). The box represents the three quartiles: the lower part of the box indicates the first quartile (the cost is lower than this amount for 25% of the persons), the upper part of the box indicates the third quartile (the cost is higher than this amount for 25% of the persons) with, in-between, the median cost. Outside the box, the two whiskers indicate the highest value and the lowest value determined as: quartile ± 1.5 × the interquartile range. In order to improve the readability of the graphs, the outlier values (defined as those above the largest value) were removed.

Figure 2. Total cost distributions of formal support (per person per month, values of the first quartiles displayed, outliers are not displayed).

Notes: For an explanation of the box plots, see the Results section. IADL (Cogn.): functional limitations on instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) with low cognitive impairment. Func.: functional limitations on IADL and basic activities of daily living (ADL). Func. Cogn.: functional limitations on IADL and ADL with significant cognitive impairment. non coh: non-cohabitant. cohab: cohabitant.

Figure 3. Total cost distributions for the National Institute of Health and Disability Insurance (per person per month, values of the first quartiles displayed, outliers are not displayed).

Notes: For an explanation of the box plots, see the Results section. IADL (Cogn.): functional limitations on instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) with low cognitive impairment. Func.: functional limitations on IADL and basic activities of daily living (ADL). Func. Cogn.: functional limitations on IADL and ADL with significant cognitive impairment. non coh: non-cohabitant. cohab: cohabitant.

Figure 4. Total cost distributions for other stakeholders (per person per month, values of the first quartiles displayed, outliers are not displayed).

Notes: For an explanation of the box plots, see the Results section. IADL (Cogn.): functional limitations on instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) with low cognitive impairment. Func.: functional limitations on IADL and basic activities of daily living (ADL). Func. Cogn.: functional limitations on IADL and ADL with significant cognitive impairment. non coh: non-cohabitant. cohab: cohabitant.

In the group Func.:

• The total cost of formal support was below €353 per month for 25 per cent of the persons. No important differences were observed according to presence level of the informal carer.

• For the NIHDI, the level of the first quartile was low: between €26 and 56 per month. Medians remained below €400 per month.

• For other stakeholders, the level of the first quartile was also low: between €33 (with a cohabitant carer) and 180 per month (with a non-cohabitant carer).

In the group Func. Cogn.:

• For 25 per cent of persons, the total cost of formal support was below €382 per month in situations with a cohabitant carer, €531 with no carer and €631 with a non-cohabitant carer.

• The cost for the NIHDI remained at a low level for half of the persons in this group: overall, the medians were below €400 per month, and the first quartile was between €49 and 116 per month.

• For other stakeholders, the cost also remained low for a large proportion of the persons in this disability group: the median was below €600 per month, and the first quartile varied between €57 (with a cohabitant carer) and 253 per month (with a non-cohabitant carer).

Discussion

The aim of the study was to estimate the direct costs of formal and informal support currently provided at home in Belgium, per disability profile and presence levels of the main informal carer.

The results show that the disability criteria used were significant determinants of cost of informal and formal support for both the NIHDI and other stakeholders. Cognitive impairment is a significant factor influencing the cost of home support for disabled older persons, as shown in other studies on dementia (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Schenkman, Zhou and Sloan2001; Quentin et al., Reference Quentin, Riedel-Heller, Luppa, Rudolph and König2010; Schwarzkopf et al., Reference Schwarzkopf, Menn, Kunz, Holle, Lauterberg, Marx, Mehlig, Wunder, Leidl, Donath and Graessel2011). Persons with cognitive impairment require more supervision outside the time spent on IADL and ADL. This result is also shown by the high proportion of cohabitant carers in this group, i.e. constant supervision is likely to be required at home. In a qualitative study, cohabitant carers who help persons with cognitive impairment reported the serious negative impact on them personally, as they are unable to go out (Cès et al., Reference Cès, Flusin, Schmitz, Lambert, Pauwen and Macq2017b).

The comparison of our results with previous studies is difficult to perform because of the diversity of methods (perspective, cost components, definition of informal care, target population, etc.) (Quentin et al., Reference Quentin, Riedel-Heller, Luppa, Rudolph and König2010) and lack of studies on disability of older persons living at home.

In our sample, a large majority of disabled elderly persons were supported by at least one informal carer. Only 5 per cent of persons in the group with the highest level of disability and 16–17 per cent of persons in the other two groups of disability had no informal carer. Similar figures were observed in France for disabled older persons with at least three different needs for help with IADL and ADL (Paraponaris et al., Reference Paraponaris, Davin and Verger2012). In our study, in the three disability groups, the cost of informal care accounted for more than half of the total cost of the support. For the group IADL (Cogn.), informal care cost represented 68 per cent of the total cost of support, in the group Func. it was 64 per cent while this number was as high as 76 per cent for the group Func. Cogn. This is in line with previous studies on dementia (Quentin et al., Reference Quentin, Riedel-Heller, Luppa, Rudolph and König2010; Schwarzkopf et al., Reference Schwarzkopf, Menn, Kunz, Holle, Lauterberg, Marx, Mehlig, Wunder, Leidl, Donath and Graessel2011). In France, the cost of informal care provided to disabled older persons was estimated to be two-thirds of the total cost of support (Paraponaris et al., Reference Paraponaris, Davin and Verger2012). Table 5 shows the results of the sensitivity analysis of the cost estimates of informal care. In our study, this cost component was highly dependent on the living arrangement of the carer: between €1,050.8 and 2,086.6 for non-cohabitant carers, and between €3,549.4 and 6,311.7 for cohabitant carers. The share of the informal care cost, based on living arrangements, varied between 51 and 58 per cent for non-cohabitant carers, and between 81 and 86 per cent for cohabitant carers (according to the disability profiles). These results were in line with the observations of De Koker (Reference De Koker2009) in Flanders that co-residence allowed more intensive informal care. Overall, using either the OCM or CVM leads to lower cost estimates of informal care (Table 5). Informal care costs for non-cohabitant carers represented between 36 and 46 per cent of the total cost, while in situations with a cohabitant carer, the proportion remained high (about 70–78% of the total cost).

Table 5. Informal care average cost estimates (per person per month), sensitivity analysis

Notes: Ninety-five per cent confidence intervals are in parentheses. IADL (Cogn.): functional limitations on instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) with low cognitive impairment. Func.: functional limitations on IADL and basic activities of daily living (ADL). Func. Cogn.: functional limitations on IADL and ADL with significant cognitive impairment.

Concerning only the cost of formal support, other stakeholders were the main funding body. They accounted for more than half of the total cost of formal support in the three disability groups (between 57 and 74%) and were always significantly lower in situations with a cohabitant carer. Hence, the NIHDI did not finance the main part of formal home support costs, even in the highest level of disability group. This result may be partially due to low costs of various healthcare services that support the disabled elderly at home: nursing care, physiotherapy and speech therapy. At home, the average costs of these similar services were much lower than in nursing homes. In our sample, only for these health services, these average costs, per person, per month, were €166 in the group IADL (Cogn.), 378€ in the group Func. and €517 in the group Func. Cogn. In contrast, in nursing homes, such healthcare services had an average total cost of €1,632 per resident in Belgium in 2017 (unpublished statistics provided by the NIHDI, for all disability profiles in nursing homes). The public funding of nursing home beds is based on a case-mix system determined by disability profiles of residents and the number of healthcare staff (Van den Bosch et al., Reference Van den Bosch, Willemé, Geerts, Breda, Peeters, Van De Sande, Vrijens, Van de Voorde and Stordeur2011). Hence, according to the average cost of formal support at home, reimbursed long-term healthcare services are much less provided at home than in nursing homes.

A deeper analysis revealed that cost sharing for the NIHDI was slightly higher in situations with a cohabitant carer because of the lower use of home care services (domestic help, home care worker and meals-on-wheels). This result is consistent with the hypothesis that cohabitant carers are a substitute for home care services. In the group with functional limitations, in situations with cohabitant carers, the savings of home care services almost compensated the higher costs observed for the NIHDI. This can be explained by a higher cost for personal nursing care because of a higher level of functional limitations of care recipients with a cohabitant carer than in the other two groups (no carers and non-cohabitant carer). Within the group Func. Cogn., the cost savings of home care services were even greater in situations with a cohabitant carer. Furthermore, for these situations, the total cost of formal support was significantly lower in situations with a cohabitant carer than in situations with a non-cohabitant carer, despite the high level of disability of the care recipients. All persons in the two disability groups with significant functional limitations (with or without cognitive impairment) were eligible for social care (domestic help, home care worker) and nursing care services. In these two groups, first quartiles and median costs of formal support suggested a low level of utilisation of formal support: in the group with the highest level of disability, Func. Cogn. (e.g. average total cost for the NIHDI below €57 per month for 25 per cent of persons with a cohabitant carer). One of the possible explanations for low levels of formal care service use is the difficulty in accessing information on these existing services in Belgium (Anthierens et al., Reference Anthierens, Willemse, Remmen, Schmitz, Macq, Declercq, Arnaut, Forest, Denis, Vinck, Defourny and Farfan-Portet2014; Willemse et al., Reference Willemse, Anthierens, Farfan-Portet, Schmitz, Macq, Bastiaens, Dilles and Remmen2016; Cès et al., Reference Cès, Flusin, Schmitz, Lambert, Pauwen and Macq2017b), which may be exacerbated in situations with no carer or with an aged carer.

Strengths and limitations

We acknowledge the various limitations of our study. First, the estimate of the direct cost of disability was based on an empirical approach (expenditure-based versus living standard approach) (Berthoud, Reference Berthoud1991) and does not allow for normatively determining the average costs according to the need for support. The cost observed by using the expenditure-based approach depends on many other factors, such as income constraints of disabled older persons, geographic availability, access to information, etc. Moreover, for cost estimates, some components were excluded as no data were collected, such as the cost to adapt the house for mobility or safety reasons, supplements paid for healthcare services linked to disability, the cost of transportation of informal carers to get to the care recipient's dwelling, the cost of support provided by other informal carers (particularly in situations with a non-cohabitant carer) and the possible overuse of other resources (e.g. heating, transportation facilities, etc.). Lastly, the cost of co-ordinating formal support was not included.

A second limitation is that the use of the replacement method to value informal care requires a valid and accurate time measurement. For cohabitant carers, time spent on helping activities is less clearly delimited than for non-cohabitant carers, which is mostly determined by physical presence at the care recipient's dwelling. Furthermore, some activities are not easily identifiable, such as supervision, which is likely to be mixed with ‘being-on-call’ (not included in the time measurement) (Cès et al., Reference Cès, de Almeida Mello, Macq, Van Durme, Declercq and Schmitz2017a). Moreover, the need for supervision is determined subjectively by informal carers and may not correspond to the same appreciation by professionals. For high values of the time spent on caring, overestimation is probable for cohabitant carers and when care recipients have a low or medium level of disability, even after data cleaning. The replacement method also relies on a strong hypothesis: formal care is equivalent to informal care (in efficiency and quality) and from the point of view of both the informal carer and care recipients (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Brouwer and Koopmanschap2004, Reference van den Berg, Brouwer, van Exel, Koopmanschap, van den Bos and Rutten2006; Koopmanschap et al., Reference Koopmanschap, van Exel, van den Berg and Brouwer2008). Thirdly, cost unit should correspond to the one of the professional who would replace informal carers. We lacked detailed data on time spent for personal care, which would allow a more accurate cost unit estimation by using a higher hourly rate of a trained home care worker or a nurse (between €22.04 and €30 for nursing care). Moreover, in case of high levels of disability (e.g. significant cognitive impairment), professionals who would replace informal carers should also be trained to look after highly disabled care recipients and would, thus, be more costly than a home care worker (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Brouwer, van Exel, Koopmanschap, van den Bos and Rutten2006). The cost of informal support is likely to be underestimated, since only the time spent on caring by the main informal carer was included in the estimation.

Fourth, another limitation is regarding selection bias. A significant proportion of disabled older persons may not be included, as they may not apply for formal help for many reasons such as lack of knowledge of existing formal support and lack of awareness of needs, refusal of formal support, financial constraints (Casado et al., Reference Casado, van Vulpen and Davis2011; Anthierens et al., Reference Anthierens, Willemse, Remmen, Schmitz, Macq, Declercq, Arnaut, Forest, Denis, Vinck, Defourny and Farfan-Portet2014; Willemse et al., Reference Willemse, Anthierens, Farfan-Portet, Schmitz, Macq, Bastiaens, Dilles and Remmen2016). The proportion of the situations with no carer or with a cohabitant carer is thus likely to be underestimated, as the older persons involved are less likely to seek formal help than those with non-cohabitant carers. The range of socio-economic statuses observed in our sample may also not fully represent the entire population of disabled elderly persons as municipalities of low fiscal income households may be underrepresented in our sample.

However, this study is unique for several reasons. On the methodology, we provide a clear delineation of the formal care services included in the cost estimates as there is a need for standardisation of the costing estimation, as mentioned with the cost of illness for dementia (Jönsson and Wimo, Reference Jönsson and Wimo2009; Quentin et al., Reference Quentin, Riedel-Heller, Luppa, Rudolph and König2010). The methodology to assess time spent on informal care was both carefully and explicitly delimited (Cès et al., Reference Cès, de Almeida Mello, Macq, Van Durme, Declercq and Schmitz2017a) (e.g. the exclusion of ‘normal’ tasks) as recommended (van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, Brouwer, van Exel, Koopmanschap, van den Bos and Rutten2006; Wimo et al., Reference Wimo, Jönsson, Fratiglioni, Sandman, Gustavsson, Sköldunger and Johansson2016). Data were adjusted according to an explicit justification (limit of 17 hours per day) on the issue of overestimation of time spent for informal care as noted by Jönsson and Wimo (Reference Jönsson and Wimo2009). Finally, the large sample size allowed an accurate calculation of cost estimates per disability profile and presence level of the informal carer in order to benchmark costs. This method overcomes the difficulty of normatively defining the amount of resources required since the concept of need is highly relative to the context and perspective (Wilkinson-Meyers et al., Reference Wilkinson-Meyers, Brown, McNeill, Patston, Dylan and Baker2010; Harrison et al., Reference Harrison, Young, Butow and Solomon2013).

Conclusion

Our results highlight that informal care costs are the main component of total cost of home support for community-dwelling, disabled older persons. With the ageing population, promoting community-based support may increase the already high costs borne by families. Moreover, there might currently be an underuse of formal support likely to result in critical situations. Indeed, in the two groups with high levels of disability, a significant proportion of persons had relatively low levels of formal support costs (e.g. in the group with high level of disability with no carer). With the rapid demographic change, such issues might be reinforced with the risk of shortage of long-term care services. Hence, to prevent the worsening of situations of disabled older persons and their informal carers, a better detection of seriously disabled older persons living at home with low levels of formal support is crucial.

Author contributions

All authors contributed substantially to the work.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (NIHDI), the federal organisation that manages and supervises the application of the health compulsory insurance in Belgium.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of each university in the consortium (B40320108337) and the Belgian privacy commission (No. 10/028 modified by CSSSS/16/024).