Introduction

The scholarly examination of abuse committed against older adults addresses the violence perpetrated against older adults. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), elder abuse is defined as single, inappropriate, recurring and harmful acts against older people (WHO, 2018). Experiencing mistreatment could have catastrophic impacts on older adults’ life, health and wellbeing (Dong, Reference Dong2015). However, older adult abuse has long received insufficient attention from the public, government and academia (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe2003; Mixson, Reference Mixson2010). Especially when compared with child abuse, older adult protection policy has developed later and has made slower progress in the United States of America (USA) (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe2003; Teaster et al., Reference Teaster, Wangmo and Anetzberger2010). Furthermore, few studies to date have been concerned with older adult protection policy. The reality of the asymmetry in the problem of abuse and the attendant research gap highlights the necessity to improve the current policy system to protect older adults against abuse. This paper compares older adult and child protection policies, explores why older adult protection policy is less developed than child protection policy and suggests how to improve older adult protection policy by emulating what has been learned from child protection policy.

Analytic framework: Dimensions of Choice

The Dimensions of Choice Framework is one of the most popular frameworks used to analyse social welfare policy within the social work discipline (Karger and Stoesz, Reference Karger and Stoesz2018). It developed under the institutional approach that posits individual deficiency to be attributed to institutional failure and argues that welfare services should be provided as remedial measures (Gilbert and Terrell, Reference Gilbert and Terrell2002). Gilbert and Terrell (Reference Gilbert and Terrell2002: 61) indicated that social welfare policy could be interpreted as ‘choices among principles determining what benefits are offered, to whom they are offered, how they are delivered, and how they are financed’. In other words, researchers can analyse the bases of resource allocation, type of provisions, strategies of delivery and ways to finance social welfare policy. These dimensions are examined on three axes: range of alternatives, social values, and theories or assumptions.

A similar framework has been applied in comparing social care for children and older adults across seven countries in Europe (Rostgaard and Fridberg, Reference Rostgaard and Fridberg1998), social protection for dependent older adults in Europe (Pacolet et al., Reference Pacolet, Bouten, Lanoye and Versieck1999), quality of social services (Alber, Reference Alber1995) and state education projects in the USA (Sosulski and Lawrence, Reference Sosulski and Lawrence2008). Therefore, this study will use the Dimensions of Choice Framework to examine differences between older adult protection policy and child protection policy.

When applying the Dimensions of Choice Framework, this study will mainly describe the differences among the four dimensions between the two policies. However, the three-axes explanation framework in Dimensions of Choice will not work well considering that older adult protection policy is modelled from child abuse policy and uses a similar system within the same socio-political context. Besides, Dimensions of Choice is usually applied in research about social work interventions or service programmes. Further, to explain clearly the reason why the differences exist between the two policies, Dimensions of Choice is combined with a leading theory of the policy process, the Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF).

Theory: Advocacy Coalition Framework

The ACF is a widely used theory-driven framework that synthesises the top-down and bottom-up approaches to the policy process and addresses changes in policy implementation (Sabatier, Reference Sabatier1988). ACF assumes some individuals or group actors with shared belief systems will generate advocacy coalitions to act on the same issue and compete with other opponents until they succeed in converting their shared beliefs into policy outputs and further achieve the desired policy change or impact. Policy sub-systems, including advocacy coalitions, policy brokers and others, are the basic elements of the policy process. Sub-system actors try to apply strategies to affect policy and learn to change or compromise to promote policies in the long run (Jenkins-Smith et al., Reference Jenkins-Smith, Nohrstedt, Weible, Sabatier, Sabatier and Weible2014).

Relatively stable parameters shape the coalitions’ long-term opportunity structure, while external events constrain the information, resources and network of sub-systems. These impact further feedback into sub-systems and result in policy change (Sabatier and Weible, Reference Sabatier, Weible, Fischer and Miller2006). Another important component of ACF is policy-oriented learning, whereby coalitions adjust their strategies. ACF indicates four pathways to explain the policy process or policy changes: external sources, internal structure, policy-oriented learning and negotiated agreements between coalitions (Weible et al., Reference Weible, Sabatier, Jenkins-Smith, Nohrstedt, Henry and DeLeon2011; Jenkins-Smith et al., Reference Jenkins-Smith, Nohrstedt, Weible, Sabatier, Sabatier and Weible2014). This paper uses the ACF to explain why there are differences between child and older adult protection policies. Combining the Dimensions of Choice Framework and ACF theory can describe and explain the comparison of the two policies well and further provide a cross-disciplinary link between social work and public policy studies.

Older adult abuse in the USA

Definition, prevalence, risk factors and outcomes

Currently, there is no consensus about the definition of older adult abuse in the USA. Based on the Older Americans Act (OAA), the definition of older adults refers to people aged 60 and above. Older adult abuse, also called older adult mistreatment or older adult maltreatment, could be considered as any action of harm or loss to an older person. Older adult abuse could be categorised as physical abuse, emotional/psychological/verbal abuse, sexual abuse, financial exploitation and care-giver/self-neglect (American Psychological Association, 2017; National Committee for the Prevention of Elder Abuse, 2017). Researchers and practitioners have found it difficult to determine the extent of harm perpetrated on older adults. Clinicians or medical professionals could screen for cases of abuse based on symptoms of physical pain or injury, but it is more difficult to measure the afflictions caused by emotional or financial abuse (Lachs and Pillemer, Reference Lachs and Pillemer1995). The most controversial aspect of older adult abuse is neglect, which raises difficult questions about understanding by older adults or care-givers of what constitutes adequate care. Many statutes fail to define what constitutes neglect (Mixson, Reference Mixson2010). Currently, there is no uniform definition in states’ statutes (Daly and Jogerst, Reference Daly and Jogerst2003).

There are no official statistics to identify the national prevalence of older adult abuse. Data that are available in some states are not comparable. Data collection regarding older adult abuse has been incremental (Mixson, Reference Mixson2010). Acierno et al. (Reference Acierno, Hernandez, Amstadter, Resnick, Steve, Muzzy and Kilpatrick2010) interviewed 5,777 adults aged 60 and above nationwide in 2008, asking about their mistreatment experience along with demographic and socio-economic information. Results indicated that abuse was common among older adults, with 4.6 per cent reporting emotional abuse, 1.6 per cent physical abuse, 0.6 per cent sexual abuse, 5.1 per cent potential neglect and 5.2 per cent financial exploitation in the past year. More recent data from a larger-scale nationwide investigation are needed to inform the current situation.

Many studies have indicated the risk factors and outcomes of older adult abuse. Dong (Reference Dong2015) systematically reviewed epidemiological and medical articles concerning older adult abuse, indicating that risk factors included socio-demographic traits, medical conditions, physical functioning, social network, social participation, mental health indicators such as depressive symptoms and loneliness, history of violence, number of family members and care-giver burden, among others. The most consistent correlates of older adult abuse were low social support and previous exposure to traumatic events (Acierno et al., Reference Acierno, Hernandez, Amstadter, Resnick, Steve, Muzzy and Kilpatrick2010; Dong, Reference Dong2015). Abuse is associated with disability, mortality, depression, long-term nursing home placement, hospitalisation and suicide, among other outcomes (Dong, Reference Dong2015).

Policy, legislation and practice

Adult protection policy was modelled after child protection policy but developed much later in the USA (Teaster et al., Reference Teaster, Wangmo and Anetzberger2010). The Public Welfare Amendments to the Social Security Act of 1962 first authorised the federal government to fund protective services, but focused mainly on child protection (Myers, Reference Myers2008). By 1974, the US government began to pay more attention to adult protective services (APS). States modelled older adult protection policy after child protection policy and established agencies to provide APS. Regulations like mandatory reporting and involuntary interventions were introduced. However, federal funding in this area has declined steadily since the 1980s (Teaster et al., Reference Teaster, Wangmo and Anetzberger2010). For example, funding of Social Services Block Grants, the primary source of federal funding to each state for protective services, has been cut by 36 per cent since 2000 and 73 per cent since its inception in 1982 (Shapiro et al., Reference Shapiro, DaSilva, Reich and Kogan2016).

The legislative process phased in even later. It was not until 1987 that the federal government introduced statutory language related to older adult abuse, neglect and exploitation under amendments to OAA. In 1992, the OAA Amendments introduced Ombudsman programmes to investigate complaints or reports of older adult abuse in long-term care institutions. The Elder Justice Act (EJA) of 2002 represented the first federal undertaking on older adult abuse issues, and enabled both public and private sectors to ‘legally, ethically, and structurally protect older people’ (Teaster et al., Reference Teaster, Wangmo and Anetzberger2010). OAA funds the National Center on Elder Abuse to provide states with the capacity to develop programmes to address older adult abuse. The EJA issues reports and recommendations regarding enforcement activities, and provides grants to sponsor community programmes, long-term care systems and research (Dong and Simon, Reference Dong and Simon2011; Dong, Reference Dong2013).

However, the legislation provided no national direction in principles or protocols for practitioners to screen older adult abuse cases or to intervene (Lachs and Pillemer, Reference Lachs and Pillemer2004; Dong, Reference Dong2013). Arguments about the definition of abuse, eligibility, scope of service, pros and cons of mandatory reporting, and involuntary intervention can confuse practitioners or impose ethical burdens on them (Macolini, Reference Macolini1995; Mixson, Reference Mixson2010). In addition, state laws had different definitions or instructions that were difficult to implement (Mixson, Reference Mixson2010). Interventions developed by overly vague law might violate older adults’ civil liberties, and no mature investigation or intervention mechanisms exist (Macolini, Reference Macolini1995). Faced with these difficulties, older adult protection practitioners had to struggle for guidance and resources (Mixson, Reference Mixson2010).

Comparison with child protection

The definition of child abuse has been less uncertain. Juvenile courts can render a judgement based on relatively clearer instructions codified in federal and local statues (Myers, Reference Myers2006). The 1974 federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) defined child maltreatment as an act to cause or impose imminent risk to children of serious harm or death. States’ definitions of child abuse vary and in some states are enshrined in criminal statutes (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016). Unlike older adult abuse, the prevalence of child abuse is measurable through national data and comparable state-level statistics (Children's Bureau, 2017).

Child abuse has been related to qualities of parents and family, such as parent personality, family structure and the parent–child relationship (Stith et al., Reference Stith, Liu, Davies, Boykin, Alder, Harris, Som, McPherson and Dees2009). Child maltreatment experiences also led to poor health outcomes including mental disorders, unhealthy life habits, risky sexual behaviours, and long-lasting negative effects on children's development into adolescence and adulthood (Trickett and McBride-Chang, Reference Trickett and McBride-Chang1995). Research on child abuse is abundant while progress on older adult abuse research has been slow. As Wolfe (Reference Wolfe2003) commented, research efforts to study older adult abuse have lagged behind the study of child abuse and domestic violence for 20 years.

The disjunction between research on child abuse and older adult abuse may be attributed in part to the longer history, better-developed legislation and experienced practice of child protection. In 1874, activists Henry Bergh and Elbridge Gerry formed the first non-governmental organisation devoted to protecting children. With the government's increased concern for social service in the 1930s, child welfare gained increasing attention. States formulated laws to establish responsibility to protect children. Especially since 1962, the government-sponsored child protective service (CPS) has spread nationally (Myers, Reference Myers2008).

CAPTA defined the role of the federal government in protecting children. Federal funds help states improve reporting, investigation, professional training of staff and regional programmes. The National Center on Child Abuse and Neglect was established to fund important research (Berrick, Reference Berrick, Gilbert, Patron and Skivenes2011). However, the expansion of the reporting system resulted in a flood of reported child abuse cases (Myers, Reference Myers2008). CPS currently is provided in several forms. For the mild cases, prevention service is the primary option. For more severe cases, out-of-home care is necessary. However, with increasing caseloads, practitioners turned to a strategy prioritising family reunification or maintenance (Berrick, Reference Berrick, Gilbert, Patron and Skivenes2011). Child protection practitioners struggled with caseload and developed new strategies, while older adult protection workers have continued to strive for more government attention and resources (Mixson, Reference Mixson2010).

Research objective

The existing literature has implied that the older adult protection policy modelled from child protection policy lagged behind and developed slower than anticipated (e.g. Wolfe, Reference Wolfe2003). However, most of the extant literature focused on only one policy and lacked comparative perspective. Some of the literature also analysed materials decades ago, highlighting the necessity to renew our understanding using up-to-date evidence (e.g. Teaster et al., Reference Teaster, Wangmo and Anetzberger2010). This study fills the above-mentioned gaps by comparing the older adult and child protection policies and providing updated evidence by synthesising recent materials. By combining the Dimensions of Choice Framework and ACF, this study not only illuminates the differences between two policies but also explains why these differences occur. Findings will further provide practical policy implications for future improvement, especially for older adult protection policy after learning from child protection policy.

Methods

This study used the qualitative synthesis method to compare child and older adult protection policies. Qualitative research synthesis is a useful approach to review existing qualitative studies or other research literature of interest to researchers and provide evidence-based information for policy and practice. Compared with other synthesis methods, such as systematic review or meta-analysis, qualitative synthesis research is flexible enough to be driven by the research agenda and able to include ‘grey’ literature while building an actionable knowledge base (Denyer and Tranfield, Reference Denyer and Tranfield2006; Tong et al., Reference Tong, Flemming, McInnes, Oliver and Craig2012).

Data collection and appraisal

Data were retrieved from various sources (e.g. government websites, law archives, national coalitions and academic journals). The searching process was iterative; that is, we sought all available materials related to either older adult abuse or child abuse. The process is similar to the snowball sampling method. We tracked down and cross-referenced the information of interest which an article/report cited or recommended. The snowball searching technique was applied particularly when we were looking for information about older adult abuse since a lot of information was unavailable in existing literature. Statistics from government reports or publications from peer-reviewed journals were preferred because they were assumed to be authoritative sources. The ‘grey’ literature, such as practitioner reports or propaganda publications from national coalitions, is also considered because such items could provide useful and updated information. We screened out unqualified items and double checked their reliability. Triangulation technique was employed to ensure the reliability of results, meaning the synthesis results have been cross-examined by information from at least two sources. The data and materials for this article were derived from various sources, including:

(1) Documents, reports and fliers from websites in both the public and private sectors, such as the Children's Bureau, Child Welfare Information Gateway, National APS Resource Center, Administration for Community Living, National Center on Elder Abuse, National Council on Aging and National Committee for the Prevention of Elder Abuse.

(2) Legislative archives from Centers for Elders and the Courts, CONGRESS.GOV.

(3) Academic publications related to older adult abuse and child abuse by searching in Google Scholar.

Analysis

We first compare child and older adult protection policies from four dimensions (Alber, Reference Alber1995; Rostgaard and Fridberg, Reference Rostgaard and Fridberg1998; Pacolet et al., Reference Pacolet, Bouten, Lanoye and Versieck1999; Gilbert and Terrell, Reference Gilbert and Terrell2002): (a) allocation (regulations, eligibility criteria, diagnosis tools and other special issues of protection service); (b) provisions (procedural (mandatory reporting), institutional (responsive mechanism) and individual (participation right)); (c) delivery (provider, process and management of delivery); and (d) finance (sources, amounts and flows). After illustrating the differences between the two policies, we further apply the ACF to explain why differences occur. Generally, we discuss how internal structure and external factors shape the development of older adult protection policy by contrasting with the child protection policy, and how policy-oriented learning strategy used by older adults protection policy was less successful.

Findings

Before we apply the Dimensions of Choice Framework to indicate the differences between older adult protection and child protection policies, we present the problem pressure of the two policy domains. As indicated in Table 1, the number of older adults is projected to exceed the number of children in 2033. By 2050, the USA is expected to have 88.5 million older adults and 79.9 million children. This study tried to compare the prevalence rates between child abuse and older adult abuse retrieved from government reports, but there was limited comparable information because national statistics about child abuse are available – CAPTA requires all states to submit annual data to the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (Committee on Child Maltreatment Research, Policy, and Practice for the Next Decade: Phase II, Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Committee on Law and Justice, Institute of Medicine and National Research Council (Committee on Child Maltreatment Research), 2014) – but no national statistics or comparable state-level data about older adult abuse exist (Mixson, Reference Mixson2010). Based on the Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (Administration for Children & Families 2010), the prevalence of child abuse is 1.71 per cent. So far, official statistics about the prevalence of older adult abuse have been unavailable. However, some estimations are found in existing scholarly research. For examples, Acierno et al. (Reference Acierno, Hernandez, Amstadter, Resnick, Steve, Muzzy and Kilpatrick2010) did a national sample study and found about 10 per cent of respondents reported abuse, many of whom suffered from financial exploitation and neglect. Another nationwide study done by Laumann et al. (Reference Laumann, Leitsch and Waite2008) suggested the prevalence rates were 9 per cent for verbal abuse, 3.5 per cent for financial abuse and 0.2 per cent for family member-related physical abuse. Cooper et al. (Reference Cooper, Selwood and Livingston2008) systematically reviewed the studies about elder abuse prevalence, finding 25 per cent of vulnerable older adults were at risk of abuse. The inconsistent findings in previous studies was attributed to the lack of a valid, reliable and adequate measure for detection (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Selwood and Livingston2008).

Table 1. Comparative descriptive analysis of problem pressure in child and older adult protection policies

Source: 1. US Census Bureau (2017). 2. Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, POP1 Child Population and POP2 Children as a Percentage of the Population Available at https://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/tables/pop2.asp. 3. Estimated number based on national sample studies (Lachs and Pillemer, Reference Lachs and Pillemer1995; Acierno et al., Reference Acierno, Hernandez, Amstadter, Resnick, Steve, Muzzy and Kilpatrick2010). 4. Prevalence rate from the Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (Administration for Children & Families, 2010). 5. Estimated prevalence rate based on national telephone survey in 2008 (Acierno et al., Reference Acierno, Hernandez, Amstadter, Resnick, Steve, Muzzy and Kilpatrick2010). 6. Estimated number by National Council on Aging (2018). 7. Statistics about child abuse are retrieved from the annual report Child Maltreatment 2015 (Children's Bureau, 2017).

However, it needs to be clarified that certain types of older adult abuse could be underestimated because of the unique features of the victims. Generally, the prevalence of physical and sexual abuse against older adults would be underestimated while the prevalence of neglect against children was difficult to estimate in the scholarly research (e.g. Lachs et al., Reference Lachs, Williams, O'Brien and Pillemer2002). There is no measure of financial abuse against children since they do not usually have assets. Additionally, the prevalence rates retrieved from various studies were conducted in different settings. Jud et al. (Reference Jud, Fegert and Finkelhor2016) suggested the impossibility of directly comparing prevalence across studies.

Finally, it is important to clarify that this study is not indicating that the two policy domains should be competing with each other for attention and resources. Nonetheless our research emphasises that advocates of older adult protection policy profitably could emulate the efforts of the proponents of child protection policy. The following section presents differences in the four dimensions using the Dimensions of Choice Framework developed by Gilbert and Terrell (Reference Gilbert and Terrell2002).

Allocation

Regulation, criteria of eligibility and diagnostic tools

OAA and EJA are the two major federal legislative actions that regulate states’ older adult abuse victim service allocation. However, they do not specify the definition of abuse, especially highly prevalent neglect and financial exploitation. Thus, no national directions exist about how to determine eligibility criteria for older APS (Macolini, Reference Macolini1995; Lachs and Pillemer, Reference Lachs and Pillemer2004; Dong, Reference Dong2013). OAA specifies the Ombudsman Program to investigate reported abuse in long-term settings. Another important piece of legislation related to older adult abuse is the Elder Protection and Abuse Prevention Act (S.178 – 115th Congress, 2016), which directs the Administration on Aging of the Department of Health and Human Service to provide funds, information and assistance for training older APS workers.

It has been difficult to detect or report older adult abuse because most such cases are characterised by financial exploitation and self-neglect in domestic settings (Lachs et al., Reference Lachs, Williams, O'Brien and Pillemer2002; Rabiner et al., Reference Rabiner, Brown and O'Keeffe2005), and clinical assessment tools are still in development (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe2003; Fulmer et al., Reference Fulmer, Guadagno and Connolly2004). Some tools have been newly developed in recent years, such as the Elder Abuse Suspicion Index (Yaffe et al., Reference Yaffe, Wolfson, Lithwick and Weiss2008) and the Older Adult Financial Exploitation Measure (Conrad et al., Reference Conrad, Iris, Ridings, Langley and Wilber2010). However, the existing assessment tools need to demonstrate improved thoroughness and validity as well as their applicability and accuracy among different clinical professionals and settings (Cohen, Reference Cohen2011; Imbody and Vandsburger, Reference Imbody and Vandsburger2011; Gallione, Reference Gallione, Dal Molin, Cristina, Ferns, Mattioli and Suardi2017).

To contrast, multiple federal laws regulate the allocation of child abuse victim services, including CAPTA, the Children's Justice Act in 1985, the Victims of Child Abuse Act in 1990, and the Child Victims’ and Child Witnesses’ Rights Law in 1990. CAPTA provides a federal foundation for states to define child abuse as ‘Any recent act or failure of parents or caregivers to present an imminent risk of serious harm’. Under this guidance, most states could address four major types of mistreatment (neglect, physical abuse, psychological maltreatment and sexual abuse) although specific details vary (Committee on Child Maltreatment Research, 2014). Child abuse also has more fully developed and acknowledged diagnostic tools for intake cases. Caseworkers screen cases based on their relevance to abuse or neglect, sufficient evidence, harm standard, substantiated risk, child's age, and so on.

Special issue

CAPTA also addresses the medical neglect of severely disabled newborns and requires states to have processes in place so that court orders could follow. For both child and older adult abuse, the legislation concerns minority groups but they are limited to indigenous Americans. The National Indigenous Elder Justice Initiative was developed to provide ‘culturally appropriate information and community education materials on elder abuse in Indian Country’, while the Indian Child Protection and Family Violence Prevention Act addresses child abuse among Indian Americans. Currently, no legislation addresses other ethnic older adult groups, and scholars have criticised the lack of cultural sensitivity (Dong, Reference Dong2012, Reference Dong2013).

Provisions

Mandatory reporting

Both older adult protection and child protection policies require mandatory reporting in federal legislation, but the child protection policy is stricter in implementation. CAPTA clearly defines that professionals such as child social workers, educators, child-care providers, medical personnel, and legal or law enforcement personnel whose work encounters children are required to report. In contrast, for older adult abuse, EJA only requires ‘owners, operators, employees, managers, agencies, or contractors of long-term care facilities that receive at least $10,000 in federal funds to report any reasonable suspicion of crimes against residents’. Penalties for failure to report include being considered guilty of a misdemeanour, resulting in fines or imprisonment.

However, arguments have arisen about the use of a mandatory reporting system and subsequent involuntary intervention for older adult abuse victims (Faulkner, Reference Faulkner1982; Rodríguez et al., Reference Rodríguez, Wallace, Woolf and Mangione2006). It is argued that a mandatory system does not respect older adults’ individual autonomy and imposes great pressure and ethical conflicts on physicians (Wei and Herbers, Reference Wei and Herbers2004). There is a trade-off between protecting older adults’ rights to be free from violence and exploitation, and maintaining their individual autonomy. Some state legislations have protected older people's autonomy to decide if they want the service.

Responsive mechanism

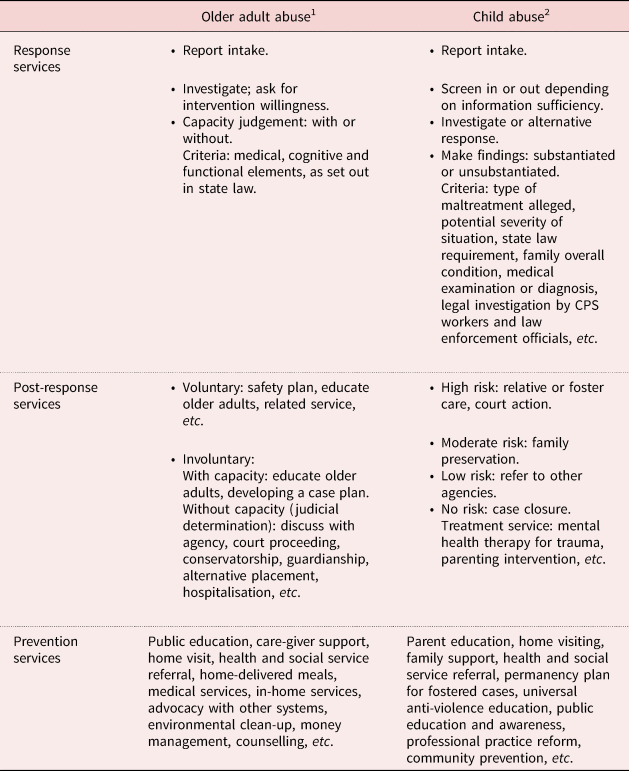

Older APS has a more-ambiguous and less-comprehensive response mechanism compared to CPS. As illustrated in Table 2, different criteria are established to intervene: for children intervention is based on risk level, while for older adults intervention is based on willingness to participate and capacity that is heavily dependent on the medical diagnosis of the older adults’ cognitive function. Usually involuntary intervention for older adults occurs for people with dementia, intellectual or developmental disabilities, mental illness, brain injuries or substance abuse, and often individuals with a combination of these conditions (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Teaster and Cassidy2017). In addition, compared to child abuse, policy related to older adults does not emphasise education for the care-giver, intervention for perpetrators, family-centred service or legal intervention (Jackson, Reference Jackson2017).

Table 2. Comparison of response mechanisms between older adult abuse and child abuse

Note: CPS: child protective service.

Source: 1. Lachs and Pillemer (Reference Lachs and Pillemer1995: figure 1). 2. Child Welfare Information Gateway (2013).

However, it needs to be pointed out that certain types of abuse prevention service are not available in the child protection system. Self-neglect and financial exploitation are the two frequent typologies in older adult abuse cases (Acierno et al., Reference Acierno, Hernandez, Amstadter, Resnick, Steve, Muzzy and Kilpatrick2010), but these forms of abuse are not well defined in the child protection system where the dominant types are neglect and physical abuse perpetrated by family members (Administration for Children & Families, 2010). The differences in prevalence of certain types of abuse further shape the focus and development of protection service for these two population groups.

Justice system

Severe abuse cases are adjudicated by the criminal justice system for both child and older adult abuse. Less-serious cases for children are referred to the Juvenile Court or Family Court, while older adult cases go to the Civil Court. The civil justice system focuses on the individual older adult victim and prevents or remedies the abuse, but currently is inadequate for issues such as financial exploitation (Stiegel, Reference Stiegel and Dong2017). The Juvenile Court legitimises the state's power to protect children when their parents or family cannot function. Thus, activities related to alternative responses, including petitions for removal and adoption, are conducted in the Juvenile Court (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2006). In this regard, the legal process of child abuse cases is usually more complicated and requires higher costs.

Participation rights of client

APS cannot compel older adults to accept services involuntarily unless with judicial determination that the client is incapable and in an emergency situation (Jackson, Reference Jackson2017). In practice, it is difficult for professionals to evaluate if older adults are capable of making free and informed decisions about their way of life and their wellbeing. The dilemma is especially true in self-neglect and financial exploitation cases (Moody and Sasser, Reference Moody, Sasser, Moody and Sasser2018). In practice, many older adults are hindered from accepting external help because of concerns about a sense of shame and fear of being placed in an institution or losing dependence on their perpetrators (Macolini, Reference Macolini1995). In reality, older adult guardianship is based on state law and there is no federal nationwide system (Wood and Quinn, Reference Wood, Quinn and Dong2017). For child abuse, there is no ethical dilemma of participation rights because children are naturally considered as incapable and dependent. Involuntary clients usually are family members; Juvenile Court may require the family or parents to co-operate (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2013).

Delivery

Providers

Most of the services are delivered by APS and CPS at the state level for older adult abuse and child abuse victims, respectively. APS serves older adults in domestic, community and institutional settings. It has flourished since the federal government claimed a leadership role in 1980. It was originally funded by federal funds that have declined steadily. As of 2016, no federal funds were appropriated for APS, which now mainly receives state financial support (Jackson, Reference Jackson2017). Its main responsibilities include conducting investigations, developing case plans and arranging placement. Another major service for older adult abuse was the long-term Ombudsman Program, developed to investigate complaints of long-term care residents. Its activity includes regular facility visits to monitor the quality of service and to advise facilities on practices. Since Ombudsmen are based on OAA, that programme receives designated federal funding (Snyder and Benson, Reference Snyder, Benson and Dong2017). CPS has a longer history since the federal government assumed leadership in child protection through CAPTA in 1974. CPS has always received steady federal financing. It conducts screenings and investigations, and provides alternative responses or additional services (Children's Bureau, 2017).

Little is known about APS and Ombudsman staff personnel profiles or demographics (Jackson, Reference Jackson2017). APS caseworkers have qualification requirements including education and pre-service training. There is no estimate of the magnitude of the APS workforce nationwide, but a national survey of APS workers in 2012 indicated that caseworkers averaged 39 cases annually (National APS Resource Center, 2012). According to the Administration for Community Living, the nationwide Ombudsman system had 1,300 staff in 2015 and an average caseload of 153 complaints. In contrast, the national data system shows 33,396 CPS workers in 44 states in 2015, with a mean caseload of 72. CPS also requires that its workers must be qualified with accredited education and years of experience.

Co-ordination

Both APS and CPS emphasise multi-disciplinary teamwork. Their caseworkers collaborate with all state and local agencies and bring outside professional expertise. Some states contract out the service to private agencies and community-based service organisations (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2013). CPS is under the supervision of the Children's Bureau in the Administration on Children, Youth and Families, of the Administration for Children & Families, within the US Department of Health and Human Services (Committee on Child Maltreatment Research, 2014). Although the National Adult Protective Services Association provides training and technical assistance, it exerts no power over APS agencies (Jackson, Reference Jackson2017).

Management

There is no standardised training model for APS or CPS. The Elder Abuse Victims Act of 2009 requires law enforcement personnel to be trained about justice-related matters, and the Office on Violence Against Women offers grants for training and service only for abused women aged 50 and above. However, no federal funds go directly to APS, so training of APS workers varies across states (Connell-Carrick and Scannapieco, Reference Connell-Carrick and Scannapieco2008). A tight budget could further weaken the quality of service provided (Lachs et al., Reference Lachs, Williams, O'Brien and Pillemer2002). A recent 30-state survey showed that 60 per cent of APS programmes have had their budgets cut 14 per cent on average, while two-thirds of the programmes averaged an increase of 24 per cent in reported older adult abuse cases (Dong, Reference Dong2013). CAPTA requires mandatory training for CPS workers, but does not establish a standardised training mode. Funding of CPS training comes from the Victims of Child Abuse Act (Committee on Child Maltreatment Research, 2014).

Finance

Source and flow

There are fewer funding sources for APS agencies (Snyder and Benson, Reference Snyder, Benson and Dong2017). They rely on multiple state-level funding streams, including appropriations from the Social Services Block Grant, OAA funding, targeted Medicaid case management funding and the US Department of Justice (National APS Resource Center, 2012). In contrast, CPS has both federal and state funding, including Grants to States for Child Abuse or Neglect Prevention and Treatment Programs, Community-based Child Abuse Prevention Grants, Promoting Safe and Stable Families, Social Services Block Grants and some family service grants (Children's Bureau, 2017).

Amount

There is great discrepancy in federal funding amounts between APS and CPS. From 2008 to 2010, the federal government invested US $7.4 billion in services for all 1.25 million child abuse victims, averaging US $5,920 per child victim, while only US $10.9 million of federal funding was allocated to 5.7 million older adult abuse victims, averaging US $1.92 per older adult victim (Snyder and Benson, Reference Snyder, Benson and Dong2017). Variation in federal funding distribution could be attributed to the different costs of legal arrangements in child and older adult abuse cases. The child abuse case management usually involves the engagement of multiple agencies (e.g. court, lawyers and CPS), which means higher costs to process and manage. The huge gap in federal funding does not necessarily mean that older adult victims’ services receive less-sufficient government support than the child victim services do.

Discussion

Summary of major differences

As the above analysis has indicated, older adult abuse faces severe challenges. The trend of population ageing worsens the situation and projects a worrisome future. There is no national direction to specify the definition of abuse, criteria of eligibility and diagnostic tools, and no national administrative agency to regulate older adult protection. Older adult abuse data systems have not been established, so little is known about the demographics of victims, service workers and organisations. Older adult abuse also has a less-developed response mechanism, with ambiguous judgement criteria and a less-comprehensive service model. Furthermore, older APS has received far less federal funding while child services were funded consistently.

Application of ACF

The ACF helps to explain the discrepancy between older adult and child protection policies in the USA. Using the three pathways indicated by Jenkins-Smith et al. (Reference Jenkins-Smith, Nohrstedt, Weible, Sabatier, Sabatier and Weible2014), the advocacy coalitions active in protection policy need to be put in context. Abuse of either children or older adults clearly is against a core belief of the US political culture for not respecting human rights and violating the value of freedom from fear, but the extent to which government should intervene is unclear. Based on shared belief about government intervention in protective services, we could categorise the advocacy coalitions into ally (more supportive) and opponent (less supportive). In promoting protection policy for children or older adults, both coalitions employ strategies to achieve their policy goals.

Internal structure

The internal conflicts between more-supportive and less-supportive advocacy coalitions are less controversial in child protection than for older adult protection. Children are generally considered incapable and vulnerable; therefore, when parents or family could not function, government could legally intervene and shoulder responsibility as parens patriae (Faulkner, Reference Faulkner1982; Macolini, Reference Macolini1995; Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2006). In contrast, it is commonly seen as less legitimate for government to intervene in older adults’ private lives, especially as the common setting of abuse is domestic. More importantly, there is less social consensus regarding older adults’ civil rights in abuse cases. Older adults have lived independently for most of their lives and still expect to be independent in most periods of their late life. When abuse happens, especially for the self-neglect and financial exploitation cases, it is difficult to determine whether it is intentional. The government or professional service providers need to assess if the older person is capable of making free and informed lifestyle decisions (Macolini, Reference Macolini1995; Moody and Sasser, Reference Moody, Sasser, Moody and Sasser2018). Therefore, there are strong internal conflicts between protecting older adults from abuse while respecting their individual autonomy.

The intensity of arguments about older adults’ autonomy can be illustrated in academic critiques of the system design for older adult abuse victims as being somewhat patriarchal (Macolini, Reference Macolini1995). Particularly, the mandatory reporting system modelled from child protection law might not be applicable to older adult abuse victims because this system assumes older adult victims, like children, are incapable of making their own decisions. Subsequently, it is not clear if it is legitimate to conduct involuntary treatment, incompetence and guardianship hearings for older adult abuse victims (Faulkner, Reference Faulkner1982). In this sense, there is less social consensus in how far government should go to protect older adults from violence while not being intrusive and patriarchal.

In addition, the public and government policy makers have lower awareness about the seriousness of abuse among older adults partly because of inadequate national statistics. Dong (Reference Dong2012, Reference Dong2013) suggested the need to conduct national longitudinal investigations, unify and standardise state databases, develop intervention studies and heighten concern about special issues. Without evidence-based theories or research, it is difficult to direct resource allocations or develop strategies for promoting policy options for older adult abuse. Another reason for low public awareness of older adult protection could be attributed to an ageism culture in the USA (Macolini, Reference Macolini1995), where older adult protection has lacked a cogent rationale in law. Government is less likely to provide funding to older adults who are seen as less dependent than children because of their life savings or pensions. Old age often is associated with negative characteristics in US society and mistreatment of older adults was not regarded as a serious problem that needed to be condemned (Macolini, Reference Macolini1995).

Finally, the efforts of the older adult protection policy ally coalition were weaker than those for child protection. Twenty-six national organisations comprise the legislative advocacy coalition for child protection policy, compared to nine promoting older adult abuse policy, according to the member lists of two national coalition websites specifically focusing on abuse prevention topics (Center of Excellence on Elder Abuse & Neglect, 2017; National Child Abuse Coalition, 2017). In addition, CAPTA directed child abuse legislative issues and the Children's Bureau administered policy implementation, while older adult protection did not have such leverage (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe2003).

External factors

Relatively stable parameters could affect the process of policy sub-systems indirectly through long-term coalition opportunity structures (Weible et al., Reference Weible, Sabatier, Jenkins-Smith, Nohrstedt, Henry and DeLeon2011). For social welfare policy, different topics competed for the allocation of limited federal funds, with older adult abuse issues not prominent enough to earn sufficient attention, resulting in a lack of APS federal funds. Views of children's and older adults’ civil rights also made it harder for older adult protection to achieve public consensus about the role of government intervention. Thus, older adult protection policy has looser regulations regarding judicial determination, mandatory reporting and involuntary intervention.

External sub-systems influenced policy changes by shaping the short-term constraints and resources of sub-system actors (Weible et al., Reference Weible, Sabatier, Jenkins-Smith, Nohrstedt, Henry and DeLeon2011). Great changes have occurred in socio-economic conditions, public opinion and governing coalitions. Although the USA is undergoing and is projected to experience rapid population ageing, Pew Research Center results estimated that only 26 per cent of respondents considered ageing as a national issue (Stokes, Reference Stokes2014). Furthermore, Americans became less supportive of expanding social welfare for older adults but more favourable towards cutting benefits (Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Angelelli and Parrott2001). The perceived role of government intervention has fluctuated greatly, and increasing legislative gridlock has made social welfare policy increasingly difficult to pass (Eggers and O'Leary, Reference Eggers and O'Leary2009).

Finally, some policies related to older adult abuse were formulated without reference to theory or research (Macolini, Reference Macolini1995). Older adult protection policy at the state level was complicated, with rapid changes and variability across different states (Mixson, Reference Mixson2010). Policy makers and legislators failed to catch up with these changes. National policy related to older adult abuse has long remained unchanged and has not provided clear direction. In contrast, child protection policy had a stronger theoretical basis and a more-developed system. With insufficient public support, increasing political gridlock and inadequate research efforts, older adult protection policy develops slowly.

Policy-oriented learning

Older APS is modelled from the child abuse victim service, but could not develop equivalently because of the underdevelopment of measurement tools, different features of abuse, higher level of conflict between coalition elements, less stimulus and weaker priorities from what should be a more supportive coalition. To start with, currently there has been no gold standard to diagnose cases or evaluate intervention programmes for older adult abuse victims (e.g. Cohen, Reference Cohen2011; Gallione et al., Reference Gallione, Dal Molin, Cristina, Ferns, Mattioli and Suardi2017). The underdeveloped techniques in older adult protection further slow the APS practice, while the guidelines in child protection policy and practice are clearer and more developed. Second, the types of abuse are relevant to the development of APS. Certain types of abuse, such as self-neglect and financial exploitation, against adults are not defined in CPS. Therefore, APS cannot learn from the child protection model but will have to build its own.

Promoting advocacy efforts to protect older adults is more controversial than to protect children, so it is harder for more-supportive and less-supportive coalitions in older adult protection policy to reach agreement. Also, the lack of national statistics means that less information is available to older adult protection coalition actors, which makes it more difficult for them to raise the level of awareness in the government and among the public. Finally, other competing priorities for the older adult ally coalition, such as Medicare, long-term care and pensions, might have tended to crowd out older adult protection issues.

Policy implications

We recommend specific legislative action to strengthen the rationale of older adult protection policy and clarify the leadership role of the federal government in protecting victims. An administrative agency, at both federal and state levels, is needed to support older adult protection, improve responsiveness, increase cultural sensitivity and establish a training model. A national data system of victim and service provider profiles should be established. Such data could facilitate academic research and further provide policy options. Advocacy coalitions supporting older adult protection should pay more attention and extend efforts promoting policy and practice. Federal funds should be allocated to APS to raise public awareness about the seriousness of older adult abuse issues.

However, it is essential to note that advocacy to promote older adult protection policy does not mean competing with child protection policy or with other welfare policies related to older adults. There is no doubt that resource allocations or policy agendas have limited space within which to operate. But, this is not a zero-sum game. Older adult protection policy could emulate or learn from child protection policy, to have a stronger and more effective role in assuring human rights in the context of a modern society with an ageing population.

Policy analysis results in this paper could shed some light on other countries’ policy regimes, considering that older adult protection is a common theme around the globe despite countries’ different political systems. A country needs to build consensus about what defines older adult abuse both through the legislative process and by practical guidance for implementation. Clear directions about how to protect older adults while respecting their autonomy should be given by the federal or central government. Accountability systems and leadership roles within different levels of government should also be established. Professional staff should engage in effective practices and should work for continuous improvement in service delivery. Finally, more advocacy efforts from various policy coalitions are encouraged, particularly to raise public awareness and secure funds for protection services.

Limitations

First, this study was essentially a descriptive analysis to show the differences between two policies when applying the Dimensions of Choice Framework because some statistics were not available or comparable. However, this study is dedicated to presenting the comparison and explaining the reasons behind these differences by connecting the evidence guided by the ACF. Despite these efforts, empirical research with comparative data is needed in the future to test our explanation. Second, this paper focuses on national-level policy, although some states may be ahead of federal policy. Future studies could compare state-level policies or practices. Domestic violence policy and practice are also ahead of older adult protection, and future studies may compare them. Third, interviews with policy makers, implementers and practitioners may contribute to learning their thoughts about older adult protection policy. Finally, this study focused on policy only in the USA. However, other countries such as the United Kingdom and Australia have a well-established older adult protection system (Phelan, Reference Phelan2013). Future research in this policy domain may benefit from conducting a cross-national comparison to address the broader range of international experiences.

Conclusion

This study compared US older adult and child protection policies. The Dimensions of Choice Framework presented differences between two policies and the ACF explained why older adult protection policy developed later and more slowly than child protection policy. It was found that older adult protection policy lacked national legislative and administrative direction, developed diagnosis and evaluation tools, a national data system, sufficient federal funds and comprehensive responsiveness mechanisms. The ACF showed that older adult protection policy developed later and more slowly than child protection policy primarily because it had less social consensus about older adults’ rights, which is how the government could protect older adult abuse victims while respecting their individual autonomy. In addition, the public and government policy makers also have had lower awareness about the older adult abuse issue. Other factors included weaker efforts of the ally coalition, increasing legislative gridlock and inadequate research evidence. To improve policy design and implementation, we suggest specific federal legislation, an administrative agency, a national data system, greater advocacy coalition effort and promoting public awareness of older adult abuse. Considering the ageing trend of the national population and the challenge of older adult abuse in the USA, efforts from all stakeholders are needed to promote a society without violence and fear.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.