Introduction

The introduction of mechanisms to enhance ‘user choice’, such as vouchers or cash-for-care benefits, has been one of the key transformations across Europe in the provision of care to frail older people. This type of care is often coined long-term care (LTC) (Da Roit and Le Bihan, Reference Da Roit and Le Bihan2010). Two principles underlie ‘user choice’. First, the notion that the users are able to act as consumers of care and make decisions about their care that best suit their needs and preferences (Prime Minister's Strategy Unit, 2005). Second, the assumption that the range of tasks and services that constitute care are similar to any other commodity (Bartlett and Le Grand, Reference Bartlett, Le Grand, Le Grand and Bartlett1993). There exists, however, a wide body of literature – mainly from the feminist critique – defining ‘care’ as encompassing much more than tasks and services. Care is defined as different to a conventional commodity given that it involves the establishment of caring relationships (Graham, Reference Graham, Finch and Groves1983; Tronto, Reference Tronto1993; Himmelweit, Reference Himmelweit1999; Fine, Reference Fine2007). The impact of this relational component on the decision to provide informal care (i.e. care by family members) has been extensively researched (Folbre and Weisskopf, Reference Folbre, Weisskopf, Ben-Ner and Putterman1998; Nelson, Reference Nelson1999). The impact of different institutional arrangements on the relationships between users and their carers has also been explored (Ungerson, Reference Ungerson2004; Yeandle et al., Reference Yeandle, Kröger and Cass2012). Much less attention has been devoted to the influence of caring relationships on the decisions made by frail older people and their satisfaction with care. This article seeks to shed some light on this gap in the literature.

This article uses the narratives of older users of English Direct Payments (DPs) to describe their decisions and examine the role of caring relationships in these decisions. More specifically, the decision to hire and employ a previously unknown ‘personal assistant’, to employ a known friend or acquaintance, or to purchase services from an agency. This article is structured as follows. The next sections summarise the several arguments concerning ‘user choice’ in LTC and review the concept of ‘care’ as defined (mostly) by the feminist and ethics of care literature. This is followed by contextual information on ‘user choice’ policies in LTC in England. The fourth section describes and justifies the qualitative methods and data used for analysis. The results are presented in the fifth section. A discussion follows, which addresses what the results add to theory and policy, before presenting the conclusions. One note on terminology. Although LTC includes both care tasks in people's own homes and communities as well as in institutions (care homes), in this article LTC refers to care provided in older people's own homes. The term ‘care’ is meant to include both feelings and emotions of concern as well as tasks, unless otherwise stated. ‘Carer’ refers to the person delivering care tasks to frail older people, whether this person is a professional or an informal carer (e.g. a family member), paid or not.

‘User choice’ in LTC

The rationale for introducing choice in LTC rests on two main arguments: as a means to achieve improved responsiveness of providers at a lower cost, and as a desirable end in itself (Bartlett and Le Grand, Reference Bartlett, Le Grand, Le Grand and Bartlett1993; Dowding and John, Reference Dowding and John2009).

The former argument is also referred to as the instrumental value of choice (Bartlett and Le Grand, Reference Bartlett, Le Grand, Le Grand and Bartlett1993). When faced with the possibility that users may choose competitors, providers have the incentive to deliver not only what users want – responsiveness – but also at the lowest possible cost – efficiency.

Choice may also have intrinsic value (Dowding and John, Reference Dowding and John2009), since choice is equated with autonomy, self-determination and ‘decisional autonomy’ (Collopy, Reference Collopy1995; Boyle, Reference Boyle2005). Opportunities to exercise choice over daily routines and activities may also be regarded as a desired outcome of good quality care (Glendinning, Reference Glendinning2008). Finally, the intrinsic value of choice is linked to the premise that people derive satisfaction from the process of choosing. It enables people to discover their own preferences, or at least experience a sense of security and control (Dowding and John, Reference Dowding and John2009).

However, both the instrumental and intrinsic value of choice in the context of LTC have been subject to criticism. Some authors point to imperfect information about providers, limited purchasing power and restricted ability to exit providers that characterises LTC (Needham, Reference Needham2006; Glendinning, Reference Glendinning2008). Another criticism highlights the (in)equitable outcomes of choice, given that imperfect information is more likely to affect poorer, less-articulate and more-isolated users (Greve, Reference Greve2009). Providers may also face incentives to select users in a context where demand exceeds supply (Scourfield, Reference Scourfield2007).

Consumerism assumptions underpinning the intrinsic value of choice have also been questioned. Some authors have expressed doubts about whether consumerism, which implies having a surplus of options to choose from, is compatible with the rationing logic inherent to scarce public services (Clarke, Reference Clarke2006; Greener, Reference Greener2007). The supposed satisfaction derived from choice has also been questioned due to the psychological costs that it entails (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2004). Among these are the ‘costs of regret’ (Thaler, Reference Thaler1980), where decisions entailing substantial implications for the future may be postponed, avoided, deferred to experts or lead to over-cautious decisions (Baxter and Glendinning, Reference Baxter and Glendinning2013). Finally, decisions involving trade-offs are more likely to generate negative emotions during the process of choosing (Lerner and Keltner, Reference Lerner and Keltner2000), a hypothesis that seems to be confirmed by empirical evidence (Netten et al., Reference Netten, Jones, Knapp, Fernández, Challis, Glendinning, Jacobs, Manthorpe, Moran, Stevens and Wilberforce2012).

Care as a relationship

The feminist scholarship has long conceptualised care around the distinction between ‘care’ as a motivation or feeling of concern for others, and ‘care’ as an action or task (Fine, Reference Fine2007), a distinction coined as caring about and caring for (Graham, Reference Graham, Finch and Groves1983). It is this relational component that sets care apart from other domestic work (Himmelweit, Reference Himmelweit1999) and brings care closer to Hochschild's (Reference Hochschild1983) concept of ‘emotional labour’, as it requires the management of the carer's emotions to create a particular feeling for the care recipient. Care tasks and care emotions are also both integral components of care-giving as expressed by the ethics of care, particularly by Tronto (Reference Tronto1993), who defined care using four principles linked to different stages of care: attentiveness as the development of awareness for the needs of others that comes from caring about someone; responsibility for planning that is linked to taking care of someone; competence in meeting the needs when caring for someone; and responsiveness from the person who receives care. Underlying the approach offered by the ethics of care is a moral disposition to care in which reliance or dependency on others, far from being avoided or deemed undesirable, is actually embedded in how people live co-dependent lives (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd2010; Barnes, Reference Barnes2011). In other words, according to the ethics of care, caring relationships are interdependent.

This interdependency means that caring relationships require the active involvement of both the carer and the person receiving care. This goes well beyond the mere collaboration required for the provision of physical tasks, rendering the user also a co-producer of care (Baldock, Reference Baldock1997). Perceived quality and satisfaction derived from the caring relationship therefore very much depend on the person receiving care, as well as the person giving it. The association between care quality and caring relationships seems to be confirmed, at least in the context of care homes, as caring relationships established between residents and staff are reported as a key aspect of perceived quality of care, particularly for people with dementia (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Davies and Nolan2009; Watson, Reference Watson2016; Canham et al., Reference Canham, Battersby, Fang, Sixsmith, Woolrych and Sixsmith2017).

Caring relationships, however, are not neutral. Kittay (Reference Kittay1999, Reference Kittay2011), first and foremost, followed by other authors (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd2004; Fine, Reference Fine2007; Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Henwood and Smith2016) defined care around power relationships marked by asymmetries. According to these authors, power inequalities within caring relationships are associated with asymmetries in the ability to self-care, disadvantaging the care recipient. This also occurs with regards to access to resources, e.g. when the care recipient is also the carer's employer. Kittay (Reference Kittay1999), however, distinguishes between the inequalities of power arising from asymmetric relationships, and the abuses of power (domination) to which both parties may be vulnerable. This includes the carers in view of their moral obligation to care, and the care recipients in view of their frailty. Only through mutual trust and respect for each other's vulnerabilities may domination be averted. Power imbalances may also reflect the particular social context in which carers provide care, as well as the nature of the care tasks. Care-giving is characterised by gender as well as class and ethnic inequalities, as care work remains not only an overwhelmingly female occupation, but one disproportionately provided by people with low levels of education, ethnic minorities or migrants. This may place the carer in a subordinate social position in relation to the person cared for. This social subordination is likely to be particularly relevant in contexts where carers are not recognised as members of a professional expert group with command over specialised knowledge (Fine, Reference Fine2014).

Power dynamics are also mediated by the locus of LTC as an activity often taking place inside older people's own homes, at the boundaries between paid and unpaid work and regulated and unregulated labour markets (Ungerson, Reference Ungerson2005). The nature of care as ‘boundary work’ is also intimately related to its relational component. The idealised labour of love is often portrayed as altruist and driven by intrinsic motivations and thus placed outside the realm of the monetised economy and the cash nexus (England et al., Reference England, Budig and Folbre2002). Professional boundaries often involve having a clear demarcation between users and professionals regarding such topics as personal details (O'Leary et al., Reference O'Leary, Tsui and Ruch2013). This can also be blurred in the context of caring relationships. The commodification of care through cash benefits – such as DPs – only exacerbates the relevance of care at the boundaries between employment and familial relationships (Ungerson, Reference Ungerson2005).

While the feminist and ethics of care literature emphasise the relational aspects of care, care remains deeply embodied. However, the embodied and relational aspects of care, far from being mutually exclusive, actually reinforce each other. Care tasks are corporeal and defined by the lived realities of the body (Lanoix, Reference Lanoix2013) in which the delivery of personal bodily care involves touch, which potentiates the development of intimacy. Touch and intimacy, both strongly gendered notions (e.g. regarding the nature of feminine and masculine ‘touches’), are in turn associated with the development of emotional bonds. Furthermore, the body is also a means of exerting power and status, as Twigg (Reference Twigg2004) points out in her example of nakedness as a potential form of subjugation in the context of bathing. Even the ethics of care literature recognises this embodied notion of care, when it refers to the ‘inevitable dependencies’ of life (Fineman, Reference Fineman1995, cited in Kittay Reference Kittay1999: 30) determined by the body.

The relational aspects of care, in the multiple dimensions described above, have important potential implications for the decisions made by users of LTC. Firstly, caring relationships become yet another characteristic of care on which users base their choice. Secondly, they reinforce the nature of care as an ‘experience good’, whose quality can only be correctly assessed by users after experiencing it. Users could overcome this problem of imperfect information by trying different providers, or by hiring carers with whom trust has long been established through shared biographies (Ungerson, Reference Ungerson2005). However, exiting a relationship with a provider might be time-consuming or emotionally exhausting, so users might be faced with high switching costs (Glendinning, Reference Glendinning2008). The quality of relationships becomes not only difficult to assess before the relationship is established, but it crucially depends on the co-producer of care – the user. Finally, if supporting those in need has a moral weight or desirability attached to it, as implied by the ethics of care, the commodification of care may substantially alter how care is experienced (Barnes, Reference Barnes2011).

The introduction of ‘user choice’ in England

The English LTC system has been transformed by a series of reforms dating back to the early 1990s. The first reforms, undertaken in 1993, introduced competition between public and private providers for the provision of care. Each Local Authority (LA) assessed needs and effectively purchased care on behalf of users from competing providers (Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Glendinning and Greener2011). From this third-party choice, more elements of ‘user choice’ and consumerism were introduced in the following decades. This was partially triggered by campaigns led by the disability movement, which drew extensively from the social model of disability (Glendinning, Reference Glendinning2008). By emphasising the distinction between impairments, borne out of the body, and disability, which results from how impairments are socially constructed as a limitation, advocates of the social model of disability urged for the reversal of power relations between carers and people with disabilities. They advocated for providing the latter with the means to choose and employ their own carers. The changes introduced arguably led to greater user choice by devolving agency to users over the choice of who provides care, when and how. Hiring ‘personal assistants’ was now also possible. These changes were gradually extended from disabled people of working age to frail older people.

Under the current system, introduced in 2007 (HM Government, 2007), older people assessed by LAs as having substantial or critical needs and meeting the means-test are allocated a Personal Budget (PB). This represents the public funds available to finance their community or home care. PBs can be used in different ways. Firstly, PBs can be managed by LAs that commission services on behalf of the user – in effect a third-party choice. A second option is to take the PB as a Direct Payment (DP) of cash, managed directly by the user. The latter may use it to either purchase care services from home care agencies, directly employ a Personal Assistant (PA), pay relatives or friends (close co-residing relatives are usually excluded) who provide care, or purchase mainstream services (e.g. taxi for transportation). When employing PAs, users are responsible for social contributions and tax payments, as well as insurance and abiding to general employment regulations (National Audit Office, 2011). Finally, the PB can also be held and managed by a home care agency chosen by the user and used when and how the user needs. In comparison with other cash-for-care benefits introduced in Europe (Da Roit and Le Bihan, Reference Da Roit and Le Bihan2010), DPs stand out as being fairly regulated as to how cash may be spent. This is unlike the Austrian and German cash allowances system, for example. Unlike similar regulated benefits introduced with a view to enhance choice and competition in LTC (e.g. in the Netherlands or Sweden), DPs are remarkable for being quite stringent regarding the employment of close family members.

In theory, by providing more sensitive market levers, DPs should increase user satisfaction by stimulating providers’ responsiveness. It should also allow a better matching of users and providers by increasing the diversity of providers and empowering users to shape care according to their preferences (Le Grand, Reference Le Grand2007; Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Glendinning and Greener2011). The underlying premise of personalisation of care delivered through DPs has thus been based on individual decisions made by atomised, self-reliant, autonomous and rational agents (older people) (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd2010). However, the impact of DPs has been subject to considerable debate. The improvements observed among DP users seem to be confined to those who employed PAs, or had sufficient resources to acquire more than the bare minimum of care or pay for more than just personal care (Slasberg and Beresford, Reference Slasberg and Beresford2016). Although there has recently been a small uptake of DPs, most new users are purchasing care from agencies rather than hiring PAs (Slasberg et al., Reference Slasberg, Beresford and Schofield2012). Since its inception, take-up of DPs among older people has remained low. Reasons given for older people's reluctance to act as individual purchasers of care include increased anxiety in making decisions and managing payments, lack of information and support, a dearth of available PAs and over-cautious attitudes of care managers regarding risk management (Fernández et al., Reference Fernández, Kendall, Davey and Knapp2007; Netten et al., Reference Netten, Jones, Knapp, Fernández, Challis, Glendinning, Jacobs, Manthorpe, Moran, Stevens and Wilberforce2012). The Care Act 2014 did not fundamentally change regulations regarding DPs, although LAs must now provide PBs to all eligible persons. DPs should be provided to as many people as possible. According to the latest figures available, only 10 per cent of all PB holders aged 65 and older receive DPs (National Audit Office, 2016). There is scarce information available on the profile of older DP users, but in comparison to other PB users they are likely to have a higher ability to manage DPs on their own (National Audit Office, 2016) and have higher levels of resources (Woolham and Benton, Reference Woolham and Benton2013).

Research has explored the difference in outcomes between those using PBs and those with conventional LA-managed PBs (Baxter and Glendinning, Reference Baxter and Glendinning2013; Woolham et al., Reference Woolham, Daly, Sparks, Ritters and Steils2017). Much less is known about the motivations, processes and experiences of older people using DPs to hire PAs or purchase care from agencies, or the factors underlying this decision. DP users would in theory be closer to the notion of ‘consumers of care’ as they can in effect choose between several options of care. In particular, the role played by the relational dimensions of care in these choices has yet to be established. This study aims to explore how care as an experience good, particularly its relational aspects, affect the different decisions of frail older people and their satisfaction with care in the English context.

Two pathways regarding how the relational aspects of care can impact on older people's choice and satisfaction with care are explored. The first pathway examines the possibility to choose and directly employ the carer. This could reduce the uncertainty associated with care being an experience good by building on an existing relationship. At the very least it would enable better control of the relational aspect of care when hiring a stranger. In other words, if care is indeed defined by caring relationships as the feminist and ethics of care literature propose, having the ability to choose the carer, particularly one that is already known, should be an important driver of user choice. The second pathway explores the possibility of better shaping care to users’ needs and preferences. The premise is that being able to choose who provides care may also give users increased agency and flexibility to define when, how and what type of care they receive. For this second pathway, Kittay's concept of care – built around power dynamics – provides an added layer of analysis when studying the negotiation of care tasks between DP users and carers.

Methods

Study design

This was a qualitative study based on semi-structured face-to-face in-depth interviews with older users of DPs. Qualitative methods were chosen to understand better users’ own perceptions of the reasons for their choices, and to capture the complexity of the decision-making process and perceptions regarding satisfaction with care.

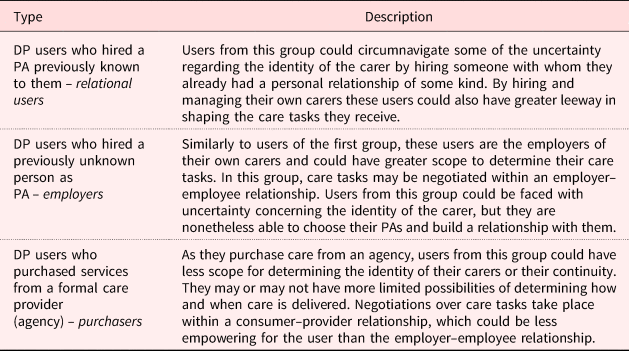

From the different deployment possibilities of PBs, those using DPs come closer to acting as ‘consumers of care’ (Rodrigues and Glendinning, Reference Rodrigues and Glendinning2015). Among these, the different uses of DPs suggest possible varying degrees of agency for older people to choose the identity of the carer. It also allows different degrees of uncertainty associated with that same choice (Table 1) – the first pathway referred to earlier. Similarly, each option might have different implications for satisfaction with care. Being able to choose who provides care (in the case of hiring a PA) may enable users to shape care to their needs and preferences – the second pathway. The different possibilities of using DPs are employed to define a typology comprising three types of DP users (Table 1): relational, employers and purchasers.

Table 1. Different ways of using Direct Payments (DPs): implications for user choice

Note: PA: Personal Assistant.

Having a typology of users defined around the different ways they chose to use their DPs provides an opportunity to contrast their choices and perceived satisfaction and identify any underlying commonality. Users from each group made different choices with their DPs, which could reflect different ways of dealing with uncertainty about the carer. They might otherwise reflect different preferences about hiring strangers, acquaintances or purchasing care from agencies. It might reveal different constraints, such as lack of suitable or affordable options. Perceived satisfaction with care and the reasons behind it can thus be contrasted and linked to the different choices made. Users with LA-commissioned services, a form of third-party choice, were purposely left out of the study.

Participants

The study included 24 English-speaking DP users aged 60 and older, residing in the community in three LAs in the Greater London area. Older adult social services of participating LAs shortlisted a total of 90 potential interviewees among their DP users. Participants were aged 60 and older; their cognitive capacity allowed them to be interviewed or they had relatives able to be interviewed as proxies. In order to minimise recall bias, shortlisted users were limited to those that had been assessed and provided with DPs for the first time in the past year. Shortlisted users were contacted directly by phone or personal contact by LA staff (LA2 and LA3), or through invitation packages containing a return consent form posted by the LA (LA1). Purposive sampling was used with the aim of achieving a balanced number of interviewees from each of the above-cited groups (Table 2). Only three interviewees had employed relatives as their PA, given the restrictions placed on the use of DPs to hire relatives. Because of the frailty of many users, particularly those with dementia, a significant share of interviews took place with proxy respondents (who were not employed as PAs). All proxy respondents were either co-residing with or very close relatives of the user and whenever possible users with mild dementia were also present during the interviews and probed about their views.

Table 2. Characteristics of the sample of older Direct Payment users

The study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Social Policy and Social Work of the University of York. Informed consent was gathered from each participant or their proxy respondents.

Data collection

Interviews were carried out between March and May 2013. All interviews took place at the user's home and lasted between 30 and 70 minutes. The interviews were semi-structured using a prepared topic guide as a starting point, which included prompts and open-ended questions covering four areas: contact with the LA, making choices with the DP, making choices regarding the carer/care received and satisfaction with care.

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Further contextual details of the user were gathered as field notes during and immediately after each interview.

Data analysis

The verbatim transcripts of the interviews were analysed using Framework Analysis (Ritchie and Lewis, Reference Ritchie and Lewis2003). This methodology involved four phases. The first phase required familiarisation with the transcripts and coding of data using the MAXQDA software. A thematic framework, or index of themes, was initially developed based on a brief review of the existing literature. It was subsequently populated with codes and adapted to reflect new emerging themes from the interviews (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Curry and Devers2007). In the second stage, data were summarised by way of thematic matrices, with each cell summarising information pertaining to each particular theme (column) and individual (row). As the cell contents were systematically analysed, some themes were grouped together into more abstract concepts. In the third stage, the thematic matrices were examined to identify patterns arising across the whole sample and subsequent similarities, associations, but also differences and deviant cases or outliers between the three groups. In the final stage of the analysis, conclusions were drawn based on the associations and exceptions found in the data.

The findings presented in the next section are organised around four headings emerging from the analysis of transcripts. These include: (a) the initial choices of users; (b) the type of relationship with the carer, and whether it was a factor affecting choice and/or perceived satisfaction with care; (c) the definition of tasks and timings, and their impact on the perceived satisfaction with care; and (d) reciprocity in caring relationships, a new theme emerging from the analysis of transcripts. For each heading the results for each of the three types of user are presented, highlighting differences and commonalities between them.

Results

Initial choices of users

A significant number of interviewees had previously received unsatisfactory care from home care agencies contracted by their LAs. Despite this, when shifting to DPs, purchaser-type users still viewed agencies as a more reliable option than employing relatives, neighbours or strangers as their PAs. They perceived agencies as being better equipped to find a back-up option in case a carer became unavailable (e.g. sickness). Unlike the other types of interviewees, purchasers expressed concern that the whole process of employing a PA and dealing with the mandatory insurance and tax responsibilities would prove too daunting. Furthermore, they had strong reservations about employing acquaintances so as not to cross the boundaries between kinship and employment relationships. They understood from the outset that they would be unlikely to be able to choose the agency carer. However, this issue, as well as continuity of carers, were seldom mentioned as factors driving their initial decision on how to deploy their DPs. Purchasers relied instead on the choice of carer made by home care agencies to whom they had delegated this decision:

I just sort of thought, oh well if I go with this agency [name omitted for confidentiality], he [agency manager] is pretty accommodating with finding the right sort of people. (LA3 010, female, purchaser, aged 87, proxy with user)

Unlike purchasers, continuity in the relationship with the carer stood out in the initial choice of relational-type users. For example, proxy respondents of users with advanced stages of dementia reported how continuity was particularly important for their relatives in accepting care, as carers would need to acquire habits of a care routine. Being able to choose the carer was therefore paramount for relational users, even if this included having overlapping kinship or friendships and employment relationships. In fact, many had chosen DPs because they already had someone in mind to become their paid carer.

Similarly, employers also prioritised continuity. Being able to determine the identity of the carer had been a clear motivation for their use of DPs. Unlike relational users, however, employers did not want to employ acquaintances, whom they felt could be overburdened or unreliable. Regarding the boundaries between employment and kinship, employers’ views were similar to those of purchasers. They expressed feeling uncomfortable receiving intimate care from relatives and had also strong reservations about mixing employment with pre-existing relationships:

When you are in a business arrangement, whatever it might be, the relationship is different, because there is power. In a friendship relationship the power is mutual, which is usually what makes the friendship work. It is not like that when money is changing hands. (LA2 007, male, employer, aged 64)

For employers, prioritising continuity while separating kinship and employment relationships meant facing a much higher uncertainty over the identity of the carer. Many expressed anxieties about having a stranger come into their house. Their narratives were quite different from purchaser and relational users, who, for different reasons, expressed no such anxieties. The former, because they delegated the decision to agencies, and the latter, because they already knew their carers. To manage imperfect information, many employer-type users based their choice of PAs on recommendations from acquaintances who also employed a carer. Others contacted user organisations and support agencies commissioned by LAs for information and support. Once a trusting relationship had been established with a hired PA, they could also become a valued source of information for employers.

Developing relationships with carers

In order to explore further the possible relevance of the relational aspects of care, interviewees were prompted to elaborate further on their relationships with paid carers and how it impacted their satisfaction with care. Although all types of interviewees valued the establishment of a bond with the paid carer, there was a wide range of relationships among the three groups of users.

The relationships with the agency carers had clearly set boundaries acknowledged by purchasers. This included, for example, views on when it was deemed appropriate to meet carers. Contacting current agency carers outside working hours was frowned upon. The relationship with agency carers was defined as a professional one – rather than friendship. It did not involve deeper emotional feelings or concern for the carer, even for long-tenured agency carers:

User: They turn up on time, that's the most important thing.

Husband: There is certain things with the carers that you might not like to personalise, you know. (LA3 002, female, purchaser, aged 80, proxy with user)

In this environment of clearly set boundaries, there was a clear awareness of the power held by those purchasing care, namely the power to end the relationship. These more detached relationships were consistent with the preferences of purchasers and reflected their decision to purchase care from agencies, which offered limited leeway in the choice of carers.

While some purchasers had actively sought to keep an emotional distance from their carers, they nonetheless acknowledged that the rapport they developed, even if detached, contributed to an improved experience of receiving care of an intimate nature. It enhanced their carers’ knowledge of user preferences and often shifting care needs. It was perceived as crucially important in managing challenging behaviour from users with dementia.

In comparison with purchasers, employer-type interviewees developed a wider range of relationships with their carers. Most developed close caring relationships that involved feelings of concern for their carers, viewing them as friends or kin-like, even though they had not previously known them. Others preferred to keep a certain distance. This mixed range of relationships also reflected the boundaries and power imbalances inherent to the employer–employee relationship. Employers, similarly to the purchasers, were very much aware of these boundaries:

It's like friends you know. It wouldn't be friends like go out to eat or something. It's just in between. Once she goes, she goes and that's it. (LA2 009, female, employer, aged 60, proxy with user)

What was clear was that being able to choose the carers and determine their continuity had enabled more control and flexibility over the development of the caring relationship:

It's whatever you want it to be, to be quite honest. I think, if you are the employer you can have the relationship with your carer how you want to have it. You want to have the distance between the two of you and I will be watching over you, you can do it. (LA2 003, female, employer, aged 60)

Concerning satisfaction with care, employers credited their rapport with carers with improving their experience of personal care in similar ways to purchasers. It was clear from the accounts of employers, however, that caring relationships were themselves viewed as an intrinsic part of their overall satisfaction with care.

Relational users had deep caring relationships with their PAs, even those that had employed acquaintances that were not relatives (e.g. neighbours). As mentioned previously, these pre-existing relationships played a role in their choice of use of DPs. Concerning the impact that caring relationships had on their perceived satisfaction with care, relational-type users held similar views to those of employers by linking caring relationships with their satisfaction with care.

The rapport established with the paid carer was thus deemed to impact on the perceived quality of care in two ways. Firstly, it improved the experience of receiving care, particularly care of an intimate nature. It contributed to better knowledge of the often-shifting care needs and preferences of users. It was also perceived as decisive in handling situations of challenging behaviour from users with dementia. At least one of these arguments was reported by nearly all respondents of each group, or their proxies. Secondly, the relationship itself was equated with satisfaction with care, by allowing users to receive emotional support and companionship. This was confined to the narratives of employers and relational-type users who employed PAs.

Definition of tasks and timings

Another potential factor impacting on perceived satisfaction was the degree of flexibility that the type of relationship between older people and their paid carers offered in negotiating the tasks and timings of care. These negotiations might also reflect different power dynamics. In general, purchaser-type users reported that their agencies were very accommodating of their needs and preferences in terms of schedules, particularly if given sufficient advance notice. Concerning the negotiation of tasks, there were noticeably fewer references to such tasks as housework help in the narratives of purchasers. There were also occasional references to a perceived lower flexibility in using DPs for certain tasks when receiving care from agencies, such as social outings. Despite this, the ability to determine tasks, including those that might not be explicitly covered in the care plan, significantly improved as interviewees spent more time with agency carers.

Employers reported great leeway in defining the timing and duration of care visits. Their narratives included descriptions of how they were able to change care schedules at a shorter notice or have PAs coming at very early or late hours. The flexibility also included the possibility of accumulating hours more easily or have PAs deliver care for longer hours than they were supposed to. Many of the PAs directly hired by employers belonged to ethnic minorities. It is possible that the setting of care schedules reflected inequalities in social status between them and White British users, or possible situations of domination as defined earlier by Kittay (Reference Kittay1999). This flexibility of care schedules notwithstanding, there was little evidence of potential abuses of power among interviewed users. In fact, the negotiation of schedules, although generally based on informal arrangements between PAs and employers, mostly involved quid pro quo arrangements in which users also adapted their schedules to fit around the PAs’ own constraints:

And it works both ways. If she needs to be somewhere earlier, she tells me and she goes! I don't sit there with a stopwatch, ‘Oh, you're 15 minutes due’. Not that! No. Adult relationship. And she knows what to do and I respect her and she respects me. Adults. (LA2 007, male, employer, aged 64)

In the descriptions of employers there were often references to tasks such as domestic chores, particularly heavier tasks, as well as social outings when relationships with PAs were closer. The closer relationships with PAs enabled several employers greater leeway in the definition of tasks as they felt more confident in approaching their carers to carry out tasks that were not in the care plan.

In both the definition of timings and negotiation of tasks, the narrative of relational-type users were identical to those of employers. Not only did the former express great leeway in the definition of tasks, with the carer often doing ‘things which are perhaps not entirely in her remits’ (LA2 008, female, relational, aged 75), they also alluded to the same type of quid pro quo arrangements concerning care schedules.

Reciprocity in caring relationships

As mentioned earlier, the analysis carried out also assessed potential power dynamics and possible situations of domination in the negotiation of tasks, particularly given the gender and ethnic background of the users interviewed and many of their PAs. In this respect, reciprocity emerged as an important aspect to understand the negotiation of tasks and definition of caring relationships. Throughout the interviews about relationships with paid carers, reciprocity was a contrasting theme in the experiences of purchasers in comparison with both relational and employer-type users.

Among relational and employer-type users, accounts of reciprocal exchanges included the exchange of symbolic ‘gifts’, but equally reflected altruistic behaviour from users towards carers. For example, one employer interviewee had willingly hired someone with a history of minor mental health issues as a PA in order to help this carer get back on her feet. Included in gift exchanges was the provision of different sorts of support to the carer, such as supporting a foreign-born carer in navigating the English tax and benefit system. Occasionally, some interviewees shared paid meals with their PAs, but as a rule gift exchanges had little monetary value and were not expressed in cash. Indeed, in the entire sample there was not one example of tipping.

On the one hand, this gift exchange, particularly the ability to listen and talk about personal or daily matters, was valued by interviewees as something that directly contributed to their perceived quality of care or satisfaction:

With a carer you need to have something private and confidential. Maybe she will tell you something private about herself. A problem with her boyfriend, or with a friend. When you get a carer after years together and get that quality and they give you good care at the same time, I think you got the package. (LA2 010, male, employer, aged 71)

Taken together with the quid pro quo arrangements regarding care schedules, these reciprocal exchanges denoted a concern for the vulnerabilities of PAs. Reciprocity was enabled by the intimacy that continuity of caring relationships allowed, which was found in a variety of situations among relational and employer-type users.

However, the opportunity to reciprocate the care received, even if just by listening to the carer's personal problems, also allowed users to regain a sense of independence in a context where they were otherwise relatively powerless and vulnerable.

Among purchasers, such a narrative of reciprocity was absent. One should bear in mind that agency carers faced greater constraints in accepting gifts from users. Nevertheless, reciprocity in the form of personal support, which could arguably still take place within care provided by agencies, was also absent from the accounts of purchasers. For example, although conversations with carers were appreciated as part of the experience of care delivery, the topics did not include the carer's personal problems:

But this lot [carers from a previous agency] were always complaining about the treatment they were getting elsewhere, it was something we didn't want. We didn't want to hear about their moans, you know, we had enough of our own, you know. (LA3 002, female, purchaser, aged 80, proxy with user)

Discussion

This study provides two main original findings regarding choice in the context of care. The first is that caring relationships impact the decisions of older DP users. For a number of users, intimate caring relationships had an intrinsic value as an outcome of care. This was emphasised by those who chose to employ PAs: all of the relational-type users and most employers. Continuity and familiarity with the same paid carer were fundamental to develop this intimacy. Hiring PAs, whose identity users could determine, enabled the latter to either benefit from pre-existing relationships or develop new ones. In fact, many of those who hired strangers as PAs went on to develop intimate caring relationships in which users felt that these previously unknown paid carers cared about them. Not all users, however, valued relationships with their carers in the same way. All the interviewees purchasing care from agencies, as well as a minority of employer-type users, preferred to have a more detached caring relationship, or at least maintain a certain distance. At the same time, those purchasing care from agencies and employing strangers as PAs also overlapped in their strong opposition to employing acquaintances as carers. This occurred even if this could have diminished uncertainty and allowed them to receive more care through greater flexibility in the negotiation of care tasks. They did not wish to cross the boundaries between employment and pre-existing kin or friendship relations. The choice made could also have been motivated by other factors such as affordability. Some users (mostly employers) mentioned that PAs were able to provide more hours of care. However, there was no discernible association between income and the choices made by users, or references to this as a main driver for the different choices made. The means-tested nature of the English home care benefits meant that none of the users had a high income.

As with care provided in other contexts (cf. Pickard, Reference Pickard2009; Watson, Reference Watson2016; Canham et al., Reference Canham, Battersby, Fang, Sixsmith, Woolrych and Sixsmith2017), caring about was an important component that directly contributed to the satisfaction with care experienced by users employing PAs. However, caring relationships could also have an instrumental value in contributing to the perceived quality of care and through that to satisfaction with care. This was a view shared by all three groups of DP users. Developing a rapport with the carer, even if more detached, could greatly improve the experience of receiving personal care. This was an example of the complex corporeal nature of care and how it intersected with caring relationships. These relationships could enhance the experience of receiving intimate care from strangers as the carers developed an awareness of the users’ needs – a concept termed attentiveness by Tronto (Reference Tronto1993). At the same time, however, discomfort with intimate care provided by carers sharing a biography with the user could also be a strong enough motive not to employ them as PAs. Rapports with carers were also instrumental in allowing users to receive not only more care – albeit only for those employing PAs – but also to negotiate care tasks outside their care plan. In this respect, the narrative of older people was similar to the experiences of disabled people of working age, for whom closer relationships with carers allowed greater leeway in how and when care was provided (Leece, Reference Leece2010). The findings reported here also echo some of the criticism of personalisation and choice, which showed that ‘how’ and ‘from whom’ (i.e. the identity of the carer) care is provided are the most important aspects regarding choice for older users (Slasberg et al., Reference Slasberg, Beresford and Schofield2012).

The second original finding of this study was the existence of reciprocal exchanges that went beyond the exchanges taking place in the context of paid jobs. Reciprocity was found in a number of caring relationships and not only among relational users. They were reported by users who valued continuity and relationships as an outcome of care (i.e. who hired PAs) and had developed intimate caring relationships. Reciprocal exchanges were strictly non-monetised. Ritualised gift exchanges have been characterised as an important way to cement relationships that are valuable but potentially uncertain and asymmetrical (Mauss, Reference Mauss1954; Caplow, Reference Caplow1982). There is an evident parallel with the user–carer dyad, as reciprocity reinforces bonds in a context where the relationship and continuity of care are valued as an outcome of care, but the paid carer may choose to leave at any time. Engaging in mutual exchanges may also be seen as a display of compliance with the ‘norm of reciprocity’, that is, the moral obligation to reciprocate which is inherent to social exchanges (Gibson, Reference Gibson1985).

The impact of the relational dimensions of care on choice and the reciprocal exchanges observed have relevant implications for both theory building and the development of ‘user choice’ policies in LTC. From a theoretical standpoint, this study presents evidence of caring relationships that developed in the context of DPs. It lends credence to those who postulate that these relationships can co-exist with the cash nexus and that relationships forged in the context of personalisation – such as those developed by employers in this study – can still exhibit the characteristics of care as defined by the feminist and ethics of care literature (Ungerson, Reference Ungerson2005; Pickard, Reference Pickard2009; Barnes, Reference Barnes2011). In fact, employers were able to choose the tone of their rapport with carers alongside a wide range of caring relationships. The role of reciprocal exchanges is, however, more complex and potentially contested. Reciprocity can be seen as a defining sign of the existence of mutually supportive and potentially non-dominating caring relationships (Kittay, Reference Kittay1999; Ungerson, Reference Ungerson2005). In other words, reciprocity would confirm the interpretation of caring relationships as entailing mutual dependencies or interdependences (Fine, Reference Fine2007; Kröger, Reference Kröger2009). It is, however, important to acknowledge that this study focused only on DP users and the voice of carers is therefore not represented in the findings. The reciprocal exchanges or quid pro quo arrangements present in the users’ narratives, e.g. regarding care schedules, might be perceived by carers as impositions from those acting as their employers and holding material power. This imbalance of power may well be exacerbated by the gender and ethnic background of many of the carers. Kittay (Reference Kittay2011: 55) expressed that ‘In a model where equal parties participate in a fair system of social cooperation, the ruling conceptions are reciprocity’. It is, however, debatable whether carers and users are indeed equal parties in the context of LTC in England. Reciprocity could also be understood in the context of motivating the carer's emotional engagement through in-kind ‘rewards’ (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1985; Roth, Reference Roth2007). Paying for love and a sense of caring may be considered objectionable to both users and carers, unless the ‘payments’ are in-kind and take place in what users and carers see as a reciprocal relationship.

The motivation behind some users’ unwillingness to employ acquaintances, despite the reduced uncertainty and greater possibility of getting more care that this option could entail, point to the impact of other factors on choice, such as norms governing what is deemed acceptable to ask from relatives. Care is thus ‘inevitably a social act and has social consequences’ (Fine, Reference Fine2005: 252) that are reflected in the choice users make. It thereby renders the rational choice theory that underpins much of the user choice and personalisation discourse ill-suited to explain fully decisions regarding care. Previous research in the context of the German LTC cash benefit has shown that preference for familial relationships could explain the use of cash benefits (Eichler and Pfau-Effinger, Reference Eichler and Pfau-Effinger2009). The results from this study portray, however, a more nuanced and to some extent contradictory picture. Nuanced, in the sense that it demonstrates that the importance of caring relationships in explaining the choice of older users goes beyond familial relationships. The picture is also arguably more contradictory since familial relationships, or at least the desire not to commodify them, also underlined strong preferences for agencies by many of the users interviewed (Ungerson, Reference Ungerson2004).

As for policy implications, first of all, caring relationships re-enforce the nature of care as an experience good. This raises questions on how to acquire information on the quality of caring relationships before they take place, as well as the nature of the regulation of the labour markets of care (Ungerson, Reference Ungerson2004). These questions were evident among users who employed strangers as PAs and point to the need to improve available information on and vetting of prospective PAs – an issue of relevance beyond England (cf. Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Winkelmann, Rodrigues and Leichsenring2016).

Secondly, the findings of this study indicate that continuity rather than exiting relationships may be a desired feature or outcome of care. Continuity of staff could thus be considered a key process indicator in the commissioning practices of public purchasers. Relationship-based care and continuity should be translated into the human resource management practices of home care agencies. Finally, user choice schemes should allow for a range of delivery options and control over different dimensions of care, including the possibility of developing a wide range of caring relationships.

User choice has gained increasing policy traction in LTC across Europe, including in countries that have traditionally relied on public monopoly for the provision of care, such as in the Nordic countries. Despite this and the wide diversity in choice that different schemes allow, there is limited evidence available on what drives the decisions of older people regarding LTC, a gap that this study helps to bridge. Although the current research has been carried out in the English context, its findings are relevant to a broader set of countries.

Limitations

This was an exploratory study based on a relatively small sample of older DP users, although the methods used allowed for an in-depth exploration of user narrative. Given the sampling procedure used, there could be scope for selection bias. DP users are unlikely to be a random sample of older users of publicly funded LTC in England as they might value relational aspects of care more than users of LA-managed care. They could therefore have self-selected into DPs. As was clear from the findings, however, the relational aspects of care were apparently not a factor in the choice of many DP users in our sample. It seems therefore less likely that they self-selected for these reasons.

A significant share of interviews took place with proxy respondents, particularly with DP users whose health condition affected their ability to express themselves, e.g. due to dementia or multiple sclerosis. The use of proxies raises important ethical issues (Pesonen et al., Reference Pesonen, Remes and Isola2011). On the one hand, reliance on proxies may further preclude the voices of actual users. Proxies may be overly cautious in allowing their relatives to take part in research. On the other hand, proxies may be able to protect potential interviewees from harm resulting from taking part in a study when the latter lack capacity for conscious informed decision. Eliminating the possibility of using proxies altogether would risk excluding particular groups from participating in research. After careful consideration, and given the relative importance of dementia among LTC users, a decision was made to include proxy respondents so as not to entirely exclude the voice of these users. From a methodological viewpoint, proxies’ answers might be considered as less reliable when questions relate to sensitive or highly subjective matters (Ettema et al., Reference Ettema, Dröes, de Lange, Mellenbergh and Ribbe2005). This is, however, somewhat tempered if proxies have close relationships with the user, and are therefore fully acquainted with the latter's preferences (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Mathiowetz and Tourangeau2004). Users with mild dementia were also present in the interviews, which allowed both users and their proxies to be probed about their decisions and satisfaction with care and for their views to be equally considered by the interviewer. The inclusion of proxies’ voices in this research was also further warranted by the fact that choice – the main object of this study – is likely to be deferred, or jointly made with close relatives in the case of dementia care. Similarly, existing studies show that older DP users are very likely to resort to family members when planning how to use their DPs (In Control, 2014).

Conclusions

Decisions involving LTC have often been conceptualised around the image of the user acting as a ‘consumer of care’, shopping around for the best service and exiting a provider whenever dissatisfied. The findings of this study suggest a more nuanced picture of the home care choice of older people. Caring relationships and boundaries between familial and employment relationships are salient factors impacting the decisions of older users and their perceived satisfaction with care. The findings also support the conceptualisation of care as comprising not only physical tasks but also relational aspects, even in the presence of cash benefits. A key aspect of the deeper caring relationships established in the context of DPs was the reciprocal exchanges that took place between users and PAs involving strictly non-monetary payments. These findings highlight relevant issues for the provision of care, such as imperfect information about the carer and the relational aspects of care. The relevance of caring relationships may impose further limits to the rational choice and consumerism theories that underline much of the user choice discourse. This is especially the case for the depiction of choice as a process unconstrained by the social environment or moral considerations, involving perfect information and based solely on cost–benefit considerations by users.

Author ORCIDs

Ricardo Rodrigues, 0000-0001-8438-4184

Acknowledgements

This article has greatly benefited from comments from Professor Caroline Glendinning and Professor Richard Cookson on earlier drafts. The author is also thankful to the three Local Authorities that agreed to take part in this study and to the users of Direct Payments interviewed. In conducting the fieldwork, the author benefited from being a visiting researcher at the Personal Social Services Research Unit at the London School of Economics.

Conflict of interest

The author confirms that there are no conflicts of interest on his part.

Ethical standards

The study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Department of Social Policy and Social Work of the University of York.