Introduction

In 2002, the United Nations, through the World Health Organization (WHO), prepared the ‘Active Ageing: A Policy Framework’ document, in which active ageing is defined as ‘the process of optimising opportunities for health, participation and security in order to enhance quality of life as people age’ (World Health Organization 2002: 12). This document is designed as a guideline for public policies on ageing. Thus, the health, security (physical and social protection) and participation of older persons in different spheres of society become priority action areas. The active ageing paradigm draws on theoretical work that promotes the involvement of older people in all areas of society (Lemon, Bengtson and Peterson Reference Lemon, Bengtson and Peterson1972; Rowe and Kahn Reference Rowe and Kahn1998).

Active ageing assumes that the participation of the older person in social, economic, cultural, spiritual and civic matters, according to their abilities, needs and preferences, has positive effects on their quality of life. More specifically, associative participation is a type of participation that meets two specific objectives of active ageing, namely recognising the value of voluntary work and promoting both the leadership of older persons and their organisations through their inclusion in the planning, implementation and evaluation of social development initiatives (WHO 2002: 51–2). Currently, both political discourse and research pay special attention to the importance of associative participation in the ageing process. However, the justification that both areas offer in promoting the associative participation of older adults are based on different logic. The logic that governs a document such as active ageing is normative logic. In other words, this document reflects objectives based on what is thought to be desirable to promote. But what is desirable from a normative point of view is not necessarily based on empirical evidence, which is the rationale behind the research field.

From a political point of view, it is always desirable to promote the civic participation of citizens, especially older people. From Tocqueville ([Reference Tocqueville1835, 1840] 2004) to Putnam (Reference Putnam1993, Reference Putnam2000), associative participation has been considered an instrument that promotes democracy. In addition, it should be remembered that the civic participation of older people may be productive to society itself (Kaye, Butler and Webster Reference Kaye, Butler and Webster2003), a proposition which has only recently been acknowledged by policy makers (Baldock Reference Baldock1999).

In recent years, empirical research has revealed many examples of the positive relationship between participation in voluntary associative activities and different aspects of personal wellbeing (Dávila de León and Díaz-Morales Reference Dávila de León and Díaz-Morales2009; Morrow-Howell et al. Reference Morrow-Howell, Hinterlong, Rozario and Tang2003: S137–8; van Willigen Reference van Willigen2000: S308; Wheeler, Gorey and Greenblatt Reference Wheeler, Gorey and Greenblatt1998). In Spain, Funes (Reference Funes2010, Reference Funes2011) found that older adults who participate in associations expressed both various general and specific personal benefits.

However, studies on the subject face methodological problems that limit the scope of the relationships found. A key problem that arises here is delimiting the direction of the relationship. So, does associative participation predict positive effects on various domains of the subjective quality of life of older adults or do the good conditions in these domains help to explain whether an older adult will participate in associations? In this case, the risk of self-selection bias is present when the characteristics of the sample subjects include aspects which can also be theoretically conceptualised as a cause and consequence of the independent variable of interest (associative participation). This problem of endogeneity (Wooldridge Reference Wooldridge2006) is also evident in the subject matter of this work, both overall measures and in specific dimensions of individual welfare as an indicator of subjective quality of life.

Although studies tend to value the importance of both objective and subjective dimensions of quality of life, the debate has not been resolved definitively (Cummins Reference Cummins2000). In fact, the WHO encompasses active ageing as part of a subjective understanding of quality of life: ‘Quality of life is an individual's perception of his or her position in life in the context of the culture and value system where they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns’ (WHO 2002: 13).

As Lau, Cummins and McPherson stated (Reference Lau, Cummins and McPherson2005: 404–5), ‘subjective quality of life, also known as subjective wellbeing, refers to how people feel about their lives. It provides a broad, global and comprehensive view of life quality, conventionally measured by questions of life satisfaction’. However, it is necessary to differentiate between global and specific levels of quality of life. Cummins, Lau and Stokes (Reference Cummins, Lau and Stokes2004: 413) point out that one of the basic approaches in studying the concept of quality of life is to try to measure the subjective component of quality of life through general satisfaction with life expressed by the individual and their satisfaction with different specific compartments (domains).

Participating in associations may contribute directly to the subjective quality of life of older people when that participation satisfies an expressive need. This need is not exclusive to any age group and may correspond to certain values such as altruistic values (Burns et al. Reference Burns, Reid, Toncar, Fawcett and Anderson2006), an idea of citizen participation linked to a sense of moral duty, just as civic republicanism raises (Maynor Reference Maynor2003), or simply a desire to continue contributing positively to society (Herzog and House Reference Herzog and House1991). So, when participating in associations, the individual would feel greater overall satisfaction with their life because this participation would cover that expressive need. However, it is also reasonable to argue an inverse relationship, i.e. subjective quality of life can act as a selection mechanism, making it more probable that those people who feel greater satisfaction with life, for example, get involved in associations. Similar evidence of this bi-directional process has been found in various literature (Hao Reference Hao2008; Thoits and Hewitt Reference Thoits and Hewitt2001).

Likewise, associative participation can affect and be affected by other specific quality of life dimensions. As different literature reviews highlight (Morrow-Howell, Hong and Tang Reference Morrow-Howell, Hong and Tang2009; Onyx and Warburton Reference Onyx and Warburton2003), the positive impact of associative participation on mental health has been suggested in numerous studies. The benefits would mainly come from aspects associated with emotional resources. These benefits would include the alleviation of stressful situations (Rietschlin Reference Rietschlin1998), an increase in self-esteem and recognition by society (Thoits and Hewitt Reference Thoits and Hewitt2001) and an improvement in the negative effects resulting from loss of roles (Mutchler, Burr and Caro Reference Mutchler, Burr and Caro2003). However, pre-existing emotional resources can also explain associative participation. Here, Li and Ferraro (Reference Li and Ferraro2006) and Hendricks and Cutler (Reference Hendricks and Cutler2004) explain associative participation as a compensation mechanism activated by older people to overcome pre-existing weak emotional resources.

Social integration at the community level is another element which may also potentially be a consequence of associative participation and a factor that explains it. On the one hand, participation would reinforce the social integration of the older adult within its immediate context (Midlarsky and Kahana Reference Midlarsky, Kahana, Midlarsky and Kahana1994: 126–88; Oman and Thoresen Reference Oman and Thoresen2000). On the other hand, community social integration is another resource which, according to Tang (Reference Tang2006: 377), the literature has identified as influential in the older person's associative participation, by increasing information and recruitment opportunities.

A less studied positive effect would be one produced through satisfaction with participation in free-time leisure activities (time not spent at work and available for hobbies and other activities that you enjoy). As indicated by Silverstein and Parker (Reference Silverstein and Parker2002), literature on quality of life has shown that leisure activities in older people are very important for their life satisfaction. In this respect, associative participation may be one of several options older people have for enjoying their free time, taking part in a gratifying activity (Fischer and Schaffer Reference Fischer and Schaffer1993). Furthermore, the satisfactory carrying out of other types of leisure activities has also been revealed as a predictor of associative participation amongst older people (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Saito, Takahashi and Kai2008: 183–4).

There is plenty of evidence that a thorough study of this relationship would also require considering the effect of different control variables as probable antecedents of either the decision to participate in associations or the subjective evaluation of different aspects of quality of life. In this respect, Morales Díez de Ulzurrún (Reference Morales Díez de Ulzurrún2006: 37, 139–41) shows how the literature has identified the importance of individual resources (sex, education, income, marital status, religiousness, etc.) when it comes to shaping attitudes and life experiences that facilitate or hinder association. What is more, all individual resources define the individual's social situation, which is an evaluative component of subjective quality of life (Brown, Bowling and Flynn Reference Brown, Bowling and Flynn2004).

Furthermore, as already mentioned, when studying the subjective quality of life, it is important to distinguish between general and specific measures. This is because, despite the fact that participation in associations has been associated with specific personal benefits, previous research shows contradictory results when wellbeing is a general measure such as ‘satisfaction with life’ (Pushkar, Reis and Morros Reference Pushkar, Reis and Morros2002: 142). In this respect, the literature review justifies the importance of using both types of variables when exploring relationships between associative participation and subjective quality of life.

The object of the research presented in this paper is to explore the possible self-selection effects of associative participation in both the overall measure of individual wellbeing (satisfaction with life) and in other specific domains (satisfaction with leisure, community social integration and emotional resources) in order to contribute to the debate on empirical bases that support active ageing in terms of older people's associative participation.

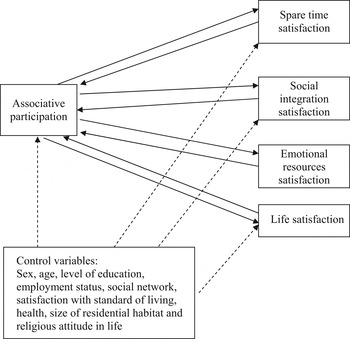

In view of the above literature, the hypothesis of this research is the existence of self-selection effects in the relationship between associative participation and subjective quality of life. That is, the relationship would be bi-directional: associative participation would act as an explanatory factor of the subjective quality of life indicators, and vice versa. In order to assess this hypothesis we used the statistical technique of structural equation modelling (SEM), a type of analysis based on linear regression that allows bi-directional relationships to be assessed. The objective of the analysis was to evaluate the coefficients between associative participation and subjective quality of life measures, after controlling the bi-directional relationships, and the effect of other control variables: sex, age, level of education, employment status, social network, satisfaction with standard of living, health, size of residential habitat and religious attitude in life.

Methods

Source and measures

The data source is the Quality of Life of Older Adults-Spain ('Calidad de Vida en Mayores-España’, CadeViMa-Spain) survey, conducted in 2008 among people aged 60 or over living in a family dwelling in Spain (Fernández-Mayoralas et al. Reference Fernández-Mayoralas, Giráldez-García, Forjaz, Rojo-Pérez, Martínez-Martín and Prieto-Flores2012). The aim of this survey was to assess the conditions and quality of life of older adults in Spain, based on the most relevant dimensions expressed by older people in previous studies (Fernández-Mayoralas et al. Reference Fernández-Mayoralas, Rojo-Pérez, Frades-Payo, Martínez-Martín, Forjaz, Rojo-Pérez and Fernández-Mayoralas2011). The 1,106-subject sample was obtained from the Municipal Register (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica [National Institute of Statistics] 2007) by random sampling stratified by sex, age group (60–70, 71–84 and 85 and over), region (14 groups) and size of the residential habitat (seven groups). The sampling error (or the error produced when the statistical characteristics of a population are estimated from a subset) was ±3.5 per cent for a confidence level of 95 per cent. Any subjects suspected of cognitive impairment (more than four errors) according to the Short Portable Mental State Questionnaire (Pfeiffer Reference Pfeiffer1975) were excluded.

The main independent variable, ‘associative participation’, was created from two questions on current frequency of participation in ‘voluntary organisations, non- governmental organisations (NGOs), voluntary work in the parish or others’ and in ‘neighbourhood, cultural or other types of clubs or associations’. This procedure enables comparison with other studies on active participation in voluntary associations (see Cnaan, Handy and Wadsworth Reference Cnaan, Handy and Wadsworth1996). The response options were: ‘every day or almost every day’ (4), ‘once or twice a week’ (3), ‘once or twice a month’ (2), ‘less frequently’ (1), ‘never’ (0) (five categories). The resulting variable, ‘associative participation’, is the sum of the values (0–4) of these two types of associative participation. Although the values of this new variable (0–8) have no clear substantive definition, this operationalisation has been chosen to make better use of the underlying information of the variable by treating it as a continuous variable.

Two types of measures have been used to measure subjective quality of life. Firstly, the ‘satisfaction with their life’ variable is used because it is the classic indicator (Andrews and Withey Reference Andrews and Withey1976; Campbell, Converse and Rogers Reference Campbell, Converse and Rogers1976) which includes the cognitive assessment of dimensions that each person considers most important for their life (Brown, Bowling and Flynn Reference Brown, Bowling and Flynn2004: 20–4). In gerontological research, there is a pronounced tendency to use subjective ratings to evaluate the life situation in old age, as pointed out by Ferring et al. (Reference Ferring, Balducci, Burholt, Wenger, Thissen, Weber and Hallberg2004: 16), while objective indicators (those which are not based on opinions or perceptions) have generally shown to be very poor predictors in measuring subjective quality of life (Cummins Reference Cummins1998). Thus, satisfaction with life as a whole is measured on a bipolar scale of 11 points, from 0 (completely dissatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied) (The International Wellbeing Group 2006). The question was as follows: ‘Thinking about your own life and personal circumstances, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole, on a scale from zero to 10? Zero means you feel completely dissatisfied. 10 means you feel completely satisfied. And the middle of the scale is 5, which means you feel neutral, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’.

Secondly, another series of variables related to specific dimensions of subjective quality of life are also used, such as spare time satisfaction, social integration satisfaction and emotional resources satisfaction, and which, as already mentioned, may be associated with associative participation. These variables are measured on the same 11-point bipolar scale. The following question was used for each of these items: ‘How satisfied are you with your spare time on a scale from zero to 10? Zero means you feel completely dissatisfied. 10 means you feel completely satisfied. And the middle of the scale is 5, which means you feel neutral, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’.

The ‘social integration satisfaction’ variable was obtained from the resulting average of an additive scale composed of various items of the Community Well-being Index (Forjaz et al. Reference Forjaz, Prieto-Flores, Ayala, Rodriguez-Blazquez, Fernandez-Mayoralas, Rojo-Perez and Martinez-Martin2011) and the Personal Well-being Index (Cummins et al. Reference Cummins, Eckersley, Pallant, Van Vugt and Misajon2003; Rodríguez-Blázquez et al. Reference Rodríguez-Blázquez, Frades-Payo, Forjaz, Ayala, Martinez-Martin, Fernandez-Mayoralas and Rojo-Perez2011). The wording of the questions referring to these items is identical to that previously mentioned for the case of spare time, although on this occasion they were asked for their level of satisfaction with: (a) ‘Trust in people living in the community where you live’, (b) ‘feeling part of the community where you live’, (c) ‘local security in the community where you live’ and (d) ‘feeling part of your community’.

The ‘emotional resources satisfaction’ variable shares the same logic, the same wording of the questions and the same measurement as the previous variable. It was obtained from the resulting average of an additive scale composed of items related to concepts such as social role, self-esteem, external recognition, autonomy and coping (Prieto-Flores et al. Reference Prieto-Flores, Fernández-Mayoralas, Rojo-Pérez, Lardiés-Bosque, Rodríguez-Rodríguez, Ahmed-Mohamed and Rojo-Abuín2008). These items measure the satisfaction with: (a) ‘their capacity to make decisions, face up to them and control their consequences’, (b) ‘the freedom they have to express their thoughts or opinions’, (c) ‘the respect and treatment they receive from others’, (d) ‘their position and recognition in society’ and (e) ‘their self-satisfaction’.

The following control variables were used: sex, age, level of education (seven levels), employment status (dichotomous variable works/does not work), social network (measured by the level of agreement with the phrase ‘there are a lot of people I can rely on when I have problems’, a dichotomous variable with the value 1 when the answer is ‘Yes’ and 0 when it is ‘More or less’ or ‘No’), satisfaction with standard of living bearing in mind their economic situation and needs (0–10), size of residential habitat (ten levels) and religious attitude in life (measured by the level of agreement with the phrase ‘My religious beliefs help me to understand or face difficult situations in life’, a dichotomous variable with the value 1 when the answer is ‘Strongly agree’ or ‘Generally agree’ and 0 when ‘Hardly’, ‘Not at all’ or ‘Slightly’). Finally, for health, the EQ-5D (The EuroQoL Group 1990) instrument descriptive system was used which records three levels of severity for five dimensions (mobility, personal care, carrying out of daily activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). The scores for these five items were converted into a single health state index by the trade-off method, with theoretical possible range of −1 and 1 (Badía et al. Reference Badía, Roset, Montserrat, Herdman and Segura1999).

Analysis

We attempted to resolve the question of the bi-directional process between associative participation and the satisfaction variables with the dimensions of life used (spare time satisfaction, social integration satisfaction and emotional resources satisfaction). Strictly speaking, only longitudinal designs help identify causal effects. In non-experimental or cross-sectional designs, the problem of endogeneity can try to be resolved by using instrumental variables (Wooldridge Reference Wooldridge2006). However, in many cases, as here, there are no suitable instrumental variables that provide reliable estimates. The use though of SEM helps to model non-experimental cross-sectional data to check complex relationship structures, including the two-way structures of possible effects. The SEM model is used to show whether the hypothesised relationships are consistent with the structure of underlying data covariance. For this it uses a series of model fit indexes under consideration. Following various recommendations (Garson Reference Garson2011; Kline Reference Kline1998), here the following goodness-of-fit statistics are used with the following cut-off criteria (Hu and Bentler Reference Hu and Bentler1999): chi-square (lack of significance reflects a general goodness of fit of data with the proposed relationships), Standardised Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR; values below 0.05 reflect a good fit), Comparative Fit Index (CFI; values above 0.95 reflect a good fit), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI; values above 0.95 reflect a good model fit), Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA; values below 0.05 reflect a good model fit).

The construction of the final model was made with the program AMOS 17.0. Analysis of missing cases (7.5% of the total) revealed in the Little's MCAR (missing completely at random) test that these were distributed completely at random, so these missing cases were rejected. The total sample used was 1,023 cases. However, the analyses were repeated with the imputed missing values (multiple imputation) and no substantial differences were found in the results.

The estimation method used was Asymptotically Distribution-Free (ADF), which does not require multivariate normal distribution. However, this estimation method requires particularly large samples, so its estimates were obtained by bootstrapping. The bootstrapping sampling distributions of the effects are empirically generated by taking a sample (with replacement) of size N from the full data set and calculating the effects in the resamples. This way, point estimates and 95 per cent confidence intervals are estimated for the effects. Confidence intervals containing zero are interpreted as not significant.

The following explains how to obtain a final model in the SEM analysis: first, estimate the initial theoretical model (see Figure 1). With this, obtain the fit indexes, which assess whether the estimated theoretical model responds adequately to the data. If this is not the case, modifications must be made to the original relationships. The modifications are made in line with statistical criteria (modification index higher than 4), as long as these modifications make sense theoretically. The resulting model is re-estimated and its fit indexes are assessed. When these fit indexes are good (according to the aforementioned goodness-of-fit statistics), it means that the final model adequately represents the structure of latent covariances in the data.

Figure 1. Bi-directional relationships between associative participation and subjective quality of life-dependent variables: initial theoretical model.

Results

The socio-demographic description of the studied population can be seen in Table 1. The total sample is mainly urban, has an average age of 72 with a slight predominance of women. Older people tend to live in households of two people, or alone, the level of education is low (common among the elderly population) and the monthly income in most cases does not exceed €900 per month.

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics

Notes: N=1,106. SD: standard deviation.

Table 2 presents the average and standard deviation of the variables used in the analysis. As this table shows, the elderly people's health is good, their associative participation is low and their social network is relatively solid. The satisfaction measurements (life satisfaction, spare time satisfaction, social integration satisfaction and emotional resources satisfaction) also offer positive results.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the used variables

Notes: N=1,106. SD: standard deviation.

The correlations between the associative participation variable and dependent variables fluctuate between 0.20 and 0.24. The final model obtained shows the estimation of all its parameters (see Table 3). The fit indexes show a good fit, with the following results: χ 2=47.19, df=33, p=0.052; TLI=0.965; CFI=0.987; SRMR=0.0237; RMSEA=0.021.

Table 3. Final model parameters: Asymptotically Distribution-Free (ADF) bootstrap estimation

Notes: Associative participation R 2=0.07; spare time satisfaction R 2=0.43; emotional resources satisfaction R 2=0.43; social integration satisfaction R 2=0.19; life satisfaction R 2=0.42.

Significance levels: * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001. Bold values show none of the relationships between associative participation and the dependent variables of subjective quality of life are significant when controlled by the model relationships structure.

As mentioned above, the parameters represented in Table 3 show the standardised regression coefficients and the correlation coefficients in the represented relationships. The main advantage of the SEM analysis is that it allows us to estimate all the represented relationships at the same time. In this case, five linear regressions were carried out simultaneously, and we took into consideration both the effect of the bi-directional relationships and the effect of other control variables. Similarly, the correlations and dependency relationships which, maintaining theoretical consistency, improve the model fit, have been added to the bi-directional relationships of the initial theoretical model. The R 2 coefficient for each of the variables is: associative participation, 0.07; satisfaction with their leisure, 0.43; satisfaction with their emotional resources, 0.43; satisfaction with their community social integration, 0.19; satisfaction with their life, 0.42.

As shown (bold values in Table 3), none of the relationships between associative participation and the dependent variables of subjective quality of life are significant when controlled by the model relationships structure. However, statistical significance was found in the beta coefficients of the rest of the relationships analysed.

Another advantage of the SEM analysis is that it is capable of estimating the effect of an independent variable on various dependent ones, taking into consideration the complex structure of relationships represented. In this case, we estimated the effect of associative participation on the different dependent variables of subjective quality of life. These effects can be direct (not mediated by any variables) or indirect (produced by the effect that associative participation has on a variable, which, in turn, has an effect on the dependent variables of subjective quality of life).

Table 4 specifically contains the total effects (direct and indirect) of associative participation with the dependent variables of subjective quality of life.

Table 4. Total standardised effects of associative participation with respect to subjective quality of life variables

Notes: Bca 95% CI: bias corrected and accelerated bootstrapping confidence interval that includes corrections for both median bias and skew. Confidence intervals containing zero are interpreted as not significant. Number of bootstrap samples=5,000.

The parameters estimated in Table 4 (point estimates) are interpreted in the same way as the beta coefficients of a linear regression. In this sense, as we can see, the most relevant aspect is that none of the parameters is statistically significant. This means that when we control the bi-directional effects and those of other control variables, participation in associations is not related to the variables of subjective quality of life analysed. That is, associative participation shows no effects, either direct or indirect, with the satisfaction variables analysed.

Discussion

As the results show, there is a weak correlation between associative participation and various dimensions of subjective quality of life. The important question here is to determine whether the relationship is maintained in multivariate models of complex relationships and to identify the direction of this relationship, which was the focus of the study.

The results of the SEM analysis show that when bi-directional effects and the complex effect of other variables are controlled, associative participation is not shown to be a predictor of any of the dependent variables analysed. Thus, participating in associations does not have statistically significant effects on the subjective quality of life of older adults in Spain, whether in an overall measurement, such as satisfaction with life, or in the other specific domain measures of wellbeing analysed. The good fit indexes of the model show consistent results.

These results support the idea that an associative participation self-selection bias could be being generated for older adults in Spain. This bias would mean, as the literature states, that there are no positive participation effects on the individual wellbeing of older adults. In other words, older adults who participate in associations have pre-existing characteristics (socio-demographic and life) which, when controlled, result in associative participation not being a significant activity for their individual wellbeing and subjective quality of life. Consequently, research supporting the positive effects of associative participation on subjective quality of life is not confirmed in this study.

Expressive needs and values that can be behind the decision to participate in associations do not appear to be sufficiently significant to affect an overall measure such as satisfaction with life. The same could be said for whatever effects associative participation might have on other specific domains not tested here. If these effects were significant, they should have been reflected in an overall measure such as satisfaction with life.

In terms of satisfaction with leisure such as the subjective quality of life domain, associative participation would be a useful instrument for fulfilling the desire for greater social interaction in old age (Clary and Snyder Reference Clary, Snyder and Clark1991) and the need for older people to significantly occupy their free time at a moment in their life cycle when they are retiring from work (Okun Reference Okun1994). However, as our results show, participating in associations has not become the preferred choice of the older adult over others to maximise their personal satisfaction, as could be predicted by adopting the interpretive framework of the socio-emotional selectivity theory (Carstensen Reference Carstensen1992, Reference Carstensen1995).

Following the same idea of the benefits of freely chosen and meaningful social interaction, it could be expected that associative participation might have some type of benefit on emotional resources (Adelmann Reference Adelmann1994; Midlarsky Reference Midlarsky and Clark1991). But this relationship is not confirmed either among older adults in Spain.

Satisfaction with social integration is another of the quality of life dimensions which associative participation might impact. In that respect, the benefits of social integration have long been reflected in literature on gerontology (Rosow Reference Rosow1967). These benefits were firstly established for the general population based on the pioneering work of Durkheim ([Reference Durkheim1897] 1951). His theories have served as a guide for subsequent studies that relate personal wellbeing to activities which, like associative participation, require a high degree of social interaction (Musick and Wilson Reference Musick and Wilson2003: 260). In particular, literature on community organising (for a review, see Ahmed Mohamed Reference Ahmed Mohamed2005) has identified social integration as an important outcome in associative participation processes. Specifically, the relationship between social participation and social integration in older persons often shows a positive association (Hyde and Janevic Reference Hyde, Janevic, Marmot, Banks, Blundell, Lessof and Nazroo2003; Ogg Reference Ogg2005). However, once again, the results reject the idea that associative participation is an activity through which older adults in Spain become more socially integrated. One might say rather that the associative participation of this population is not very ‘community-oriented’, in the sense that it does not especially encourage intra-group ties, refuting therefore one of the bases of social capital (Putnam Reference Putnam2000) and suggesting a type of associative practice with either weak personal ties to other participants or a practice where personal ties are pre-associationism. This result is in line with the potential implications of the longitudinal study of van Ingen and Kalmijn (Reference van Ingen and Kalmijn2010) who, after controlling the self-selection effects, reached the conclusion that the effects of associationism on an individual's trustworthy social network were either zero or minimal.

There is perhaps a contextual explanation for no relationship being found between participating associations and the individual wellbeing of older adults in Spain. From 1939 to 1975, Spain was under a dictatorship. This means that the current generation of older adults in Spain has been used to socialising in a context with lack of freedom and prohibition of associationism; this fact must have had an effect on how this population views activities such as participating in associations. In this case, it seems reasonable to suggest that this type of socialisation has helped associative participation not to be viewed as a preferred source of individual wellbeing. But, beyond these specific contextual characteristics, these results highlight the importance of controlling the self-selection bias if the objective is to identify the benefits of associative participation.

Naturally, other theoretical models may be compatible with the structure of relationships in this study data. As is known, the logic of SEM analysis is not to find a single ‘true’ model, but to check that the hypothetical relationships are supported empirically by the covariance matrix present in the data. Popper's logic (Popper Reference Popper1965), which underlies this, tries to find empirical support that refutes the hypotheses that sustain them, rather than prove them. In this sense, it can be stated that this work provides evidence that rejects the idea of the positive effects of associative participation on individual wellbeing and the subjective quality of life of older adults in Spain.

In any case, the results presented here do not reject the possibility that specific associative practices produce certain benefits under certain circumstances (Funes Reference Funes2010, Reference Funes2011). This field of research still needs specific data on participation experience (type of associative activity, type of association, relationship between the association and the older person, subjective evaluation of the association and activity, etc.), which has yet to become available from homogeneous data sources (Morrow-Howell Reference Morrow-Howell2010). Future research in this field should seek to obtain this specific data on the participative experience. Longitudinal designs should also be considered that help to establish with more certainty the possible causal conditions between those participative experiences and the subjective quality of life of older adults. This is the main limitation of our study. However, the SEM analysis results presented herein, being a cross-sectional study, are important because they have shown the lack of any statistically significant association between associative participation and the various measures of subjective quality of life, with a significant association being a necessary requirement for establishing a causal relationship.

Conclusions

Active ageing is a policy framework designed to guide public policies on the older population in order to improve its quality of life. Of its three main pillars of action, health, security (physical and social protection) and participation, it is perhaps the latter that has a less clear relationship with quality of life. Nevertheless, the benefits of associative participation have been the principal attraction for promoting association in this population group. But, it is difficult to establish clear directional relationships in this issue. A detailed analysis of the literature shows that not even through longitudinal studies has it yet been possible to distinguish effectively between self-selection effects and possible causal effects. When public intervention proposals are made as part of the active ageing policy framework, this does not prevent the scientific community from feeling implored to gather evidence that either supports or rejects the empirical basis of these proposals. The ultimate goal is to adopt a position on the reasons why it would be necessary to promote the associative participation of older persons.

The results obtained do not show any empirical evidence of a relationship between associative participation and the aspects of subjective quality of life and individual wellbeing considered. This is the conclusion reached when the analysis covers complex relationships between dependent and independent variables, and the bi-directional effects between associative participation and the various aspects of subjective quality of life are controlled. These results and the conditions evaluated here would, therefore, not support the introduction of programmes that aim to improve subjective quality of life and individual wellbeing of older people through associative participation.

The results found have two implications: firstly, in terms of the scope of the research, the need to control self-selection bias in studies on associative participation and individual wellbeing stands out. Secondly, it is very important for the debate on public policies designed for older adults. In this respect, an interpretation of the active ageing policy framework designed to promote their associative participation should be based on arguments other than the empirical evidence of the overall benefits that participation brings them individually. These normative arguments are easily available, because active ageing as a policy framework is not determined by empirical evidence, but rather by values, specifically the United Nations Principles for Older Persons: independence, participation, care, self-fulfilment and dignity. This means that the call to promote the participation of older persons in society is considered a value in itself, regardless of the nuances of empirical research in each context. In the case of associative participation, a call to empower older persons does not need to be based on studies that show that participating improves their subjective quality of life and individual wellbeing. This call could, therefore, be based on the possible productivity benefits that participation can also bring to the rest of society or a desire to strengthen the quality of democracy, as evidenced by some of the specific goals included in the participation pillar of the WHO.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Deputy Editor and two anonymous referees for their valuable comments that have helped improve earlier versions of this paper. This study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (National R+D+i Plan; Refs SEJ2006-15122-C02-01 and SEJ2006-15122-C02-02). The first author's current position is supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through a PhD scholarship (Ref. BES-2007-14836).