Introduction

The impact of an ageing population on the workplace is a concern for many governments internationally (Keese, Reference Keese2006). Since the mid-1990s, the policy situation has moved from one where older workers were encouraged to exit the labour market in order to make way for younger workers to one where continued labour market participation is encouraged (Phillipson, Reference Phillipson2013a, Reference Phillipson, Field, Burke and Cooper2013b; Loretto and Vickerstaff, Reference Loretto and Vickerstaff2015; Phillipson et al., Reference Phillipson, Vickerstaff and Lain2016; Taylor and Earl, Reference Taylor and Earl2016; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Loretto, Marshall, Earl and Phillipson2016). Thus, increasing numbers of older workers are remaining in work (Aliaj et al., Reference Aliaj, Flawinne, Jousten, Perelman and Shi2016). In the United Kingdom (UK), the Government has sought to remove previous barriers to the extension of working lives and give more choice to workers in the timing of their retirement. In 2011, the Default Retirement Age (DRA) was abolished (HM Government, 2011), giving more control to the employee in terms of retirement timing (HM Government, 2011), although the true extent of this is debated (Beck, Reference Beck2013). Pension ages are also increasing (Department of Work and Pensions, 2017b). Thus, many may have no choice but to carry on working because of financial necessity. In this legislative context, Annual Population Survey data show that the labour market participation of those aged 50+ has increased steadily in the last ten years in the UK. For the year to September 2006, the employment rate for those aged 50–64 years was 64.7 per cent and 6.4 per cent for those aged 65 + . This had increased to 69.9 and 10.4 per cent, respectively, by the year to September 2016.Footnote 1 Older workers are also increasingly integrated across occupations and sectors, no longer clustered in ‘Lopaq’ occupations characterised by low pay, part-time hours and requiring few qualifications (Lain, Reference Lain2012; Lain and Loretto, Reference Lain and Loretto2016).

While older workers are ever-more integrated into the labour market, and make up a greater proportion of available labour, research has consistently found a lack of systematic plans by businesses to prepare and benefit from demographic and labour market changes (see e.g. Fuertes et al., Reference Fuertes, Egdell and McQuaid2013). The UK Government has sought to raise awareness of the benefits of employing older workers amongst the business community. They have highlighted the business case for employing older workers in terms of retaining experience and firm-specific knowledge, addressing skill shortages, lowering recruitment and training costs, and meeting customer demand for an age-diverse workforce (Department of Work and Pensions, 2014, 2017a; Altmann, Reference Altmann2015). However, the effects of previous employer-focused government drives, campaigns and programmes to encourage the extension of working lives have been limited. Flynn (Reference Flynn2010: 441) commented that (in relation to retirement), ‘the business case approach to retirement has had limited impact on employers’ practices and is a weak instrument for changing the culture of retirement’. These comments have resonance with earlier findings that highlight the difficultly in changing employer attitudes and behaviours towards older workers through campaigns and programmes (Taylor and Walker, Reference Taylor and Walker1998). Consequently, it is interesting to consider whether recent government efforts to facilitate the extension of working lives have had any effect on employer policy and practice.

It is with this demographic, social and legislative landscape as a backdrop that this paper draws on qualitative research undertaken in Scotland with managers and older workers.Footnote 2 The aim of this paper is to examine (a) how managers and employees think about age and ageing in the workplace; (b) the support currently put in place for older workers and the priorities for managers to enable them to support older workers in the future; and (c) the lived experiences of the older workers who are being supported (or not). The labour process perspective that asserts that employers are driven to maximise the conversion of the potential to labour into profitable production (Thompson and Smith, Reference Thompson and Smith2009) theoretically influences this paper.

In examining the extent to which older workers are supported, this research will provide insights into the degree to which employers in Scotland are aware of the effects of an ageing population on the workplace, as well as the effects of government efforts to extend working lives. Scotland makes an interesting focus for research. Compared with the UK as a whole, Scotland has a higher median age – almost two years higher (House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee, 2016). In 2016, the proportion of people in Scotland aged 65–74 and those over 75+ years rose by 22 and 16 per cent, respectively; while those in the 25–44 year age group fell by 3 per cent (National Records of Scotland, 2017d). Population projections for the year 2041 are even more dramatic, suggesting a 7 per cent fall in the population of under 21 year olds and a 45 per cent increase in the 50+ population (National Records of Scotland (2017d). This situation has arisen from an enduringly low total fertility rate which is trending downwards – the total fertility rate stood at 1.52 in 2016 (National Records of Scotland, 2017d).

It is argued in this paper that, as increasing numbers of older workers have no choice but to remain in work, and increased focus is placed on the importance of fair and decent work (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Marsh, Nicol and Broadbent2017), age awareness will need to increase in order to support the diverse workforce, foster intergenerational relations and tackle the barriers in the workplace faced by older workers. Research to date has often focused on employer reports of organisational policies, neglecting the gap between formal policies and implemented practices (Loretto and White, Reference Loretto and White2006a, Reference Loretto and White2006b; Boehm et al., Reference Boehm, Schröder, Kunze, Field, Burke and Cooper2013). In presenting both manager and older worker accounts, this research starts to address this gap. Research on older worker's relationships with the labour market is also primarily dominated by quantitative approaches that do not necessarily glean insights into older workers as people, situated within particular work, employment and legislative contexts (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Loretto, Marshall, Earl and Phillipson2016). Drawing on narrative accounts, this paper considers how legislation has shaped how managers and older workers think about age and ageing. As such, the paper will provide insights with regards to the extent to which government efforts to publicise the business value of an age-diverse workforce (Department of Work and Pensions, 2014, 2017a; Altmann, Reference Altmann2015) have been successful given the limited success of earlier efforts (Taylor and Walker, Reference Taylor and Walker1998; Flynn, Reference Flynn2010).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In the next section, a brief overview of the literature on age management in the workplace is provided. The research methods are then described, before the research findings in relation to the policies, practices and attitudes towards older workers, and the lived experiences of older workers, are presented. The paper ends with a discussion of the implications of the research findings.

Age management in the workplace

Older people are often framed as an expensive group, responsible for the inequalities experienced by younger generations (Hurley et al., Reference Hurley, Breheny and Tuffin2017). In a context where individual identity is focused on the labour market (Beck, Reference Beck1992), the ‘problem’ of population ageing is increasingly addressed by governments internationally through a focus on (the socially legitimising force of) work and work-related activity (Biggs and Kimberley, Reference Biggs and Kimberley2013). Thus, policy has emphasised autonomy, choice and the individualisation of responsibility for income in later life, with work often framed as the panacea to the problem of powerlessness and dependency in old age (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2006; Moffatt and Higgs, Reference Moffatt and Higgs2007; Biggs and Kimberley, Reference Biggs and Kimberley2013).

These policy approaches have tended to be quite simplistic, not acknowledging the complex labour market barriers faced by older workers that extend beyond the individual. Employers and managers play a crucial role in facilitating the continued labour market participation of older workers, with an extensive literature outlining the age management policies and practices that can be used to combat age barriers, promote age diversity and maintain the skills of older workers (see e.g. Naegele and Walker, Reference Naegele and Walker2006; The Age and Employment Network, 2007; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Mayho, Robson and Sharp2016). Age management encompasses organisational policy and practice areas such as: recruitment; learning and development; job flexibility and flexible working; health protection and promotion; workplace design; benefits packages; and employment exit (Naegele and Walker, Reference Naegele and Walker2006; The Age and Employment Network, 2007; Boehm et al., Reference Boehm, Schröder, Kunze, Field, Burke and Cooper2013; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Mayho, Robson and Sharp2016). However, research has consistently highlighted that organisations may lack (systematic) age management policies and practices (see e.g. Fuertes et al., Reference Fuertes, Egdell and McQuaid2013).

A key barrier to older workers, and the development and implementation of age management policies and practices, are the pervasive, and often unfounded, stereotypes held by managers/employers about the abilities of older workers (Loretto and White, Reference Loretto and White2006a, Reference Loretto and White2006b; Posthuma and Campion, Reference Posthuma and Campion2009; Fuertes et al., Reference Fuertes, Egdell and McQuaid2013; Hsu, Reference Hsu, Field, Burke and Cooper2013; Dordoni and Argentero, Reference Dordoni and Argentero2015; Nicholson et al., Reference Nicholson, Mayho, Robson and Sharp2016). Even at the macro-level, the government rhetoric in support of the extension of working lives is imbued with ageist assumptions about both older and younger workers; sometimes almost ‘pitching’ generations against each other in terms of their perceived value (Taylor and Earl, Reference Taylor and Earl2016). At the micro-level, older workers may internalise stereotypes about their abilities, which can become self-perpetuating. Indeed, it has been argued that age awareness should also target older workers who may ‘discriminate “against themselves” by not coming forward for training or promotion’ (Loretto and White, Reference Loretto and White2006a: 327).

Older worker stereotypes are not necessarily negative. For example, older workers may be seen as highly skilled and experienced, being high in warmth, having a positive attitude, more reliable, more dependable and going beyond their job requirements (Posthuma and Campion, Reference Posthuma and Campion2009; Krings et al., Reference Krings, Sczesny and Kluge2011; Ng and Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2012; Zheltoukhova and Baczor, Reference Zheltoukhova and Baczor2016). However, in the main the research base draws attention to the negative stereotypes surrounding older workers – although it must be noted that employers and managers may at the same time hold both positive and negative views (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Chan, Snape and Redman2001; Van Dalen, Henkens and Schippers, Reference Van Dalen, Henkens and Schippers2009; Dordoni and Argentero, Reference Dordoni and Argentero2015; Kroon et al., Reference Kroon, Van Selm, ter Hoeven and Vliegenthart2018). These include beliefs that older workers are less motivated, are less keen to participate in training and/or development opportunities, are less adaptable, are resistant to change, are less productive, conflict with younger colleagues, have a shorter tenure, are costly, have poor technological abilities, and do not have up-to-date skills and qualifications (Naegele and Walker, Reference Naegele and Walker2006; Posthuma and Campion, Reference Posthuma and Campion2009; Porcellato et al., Reference Porcellato, Carmichael, Hulme, Ingham and Prashar2010; Ng and Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2012; Axelrad and James, Reference Axelrad, James, Antoniou, Burke and Cooper2016; Zheltoukhova and Baczor, Reference Zheltoukhova and Baczor2016; Kroon et al., Reference Kroon, Van Selm, ter Hoeven and Vliegenthart2018). Given these negative stereotypes, it is perhaps not surprising that research identifies that employers and managers often consider the ageing of the workforce as associated with a growing gap between labour costs and productivity (Conen et al., Reference Conen, Henkens and Schippers2012).

However, it is also not only the negative stereotypes that need to be considered as a barrier in terms of the continued labour market participation of older workers. Positive stereotypes about older workers can also perversely create barriers for older workers. For example, perceptions regarding the mentoring role of older workers may limit the (training and development) opportunities available to them (Kroon et al., Reference Kroon, Van Selm, ter Hoeven and Vliegenthart2018). There may also be expectations that older workers take on additional roles in order to make available learning opportunities to younger colleagues (Beck, Reference Beck2014). Age bias may also counteract the potentially positive characteristics of older workers (Krings et al., Reference Krings, Sczesny and Kluge2011).

The experiences of older workers, and policies and practices, are not homogenous within and across workplaces. For example, even if organisations have age management policies in place, they may not be consistently implemented on the ground (Loretto and White, Reference Loretto and White2006a, Reference Loretto and White2006b; Boehm et al., Reference Boehm, Schröder, Kunze, Field, Burke and Cooper2013; Dordoni and Argentero, Reference Dordoni and Argentero2015). In general, good practice examples of age management highlight buy-in at all levels of the organisation. There is backing from senior management, a supportive human resources (HR) environment, flexible and tailored solutions are offered, and older workers are motivated to take part (Walker and Taylor, Reference Walker and Taylor1999). However, research suggests that individual arrangements with immediate managers rather than organisational policy and practice are most influential in supporting, or otherwise, the extension of working lives (Flynn, Reference Flynn2010). Thus, it is useful to consider the attitudes of managers and any individual characteristics, such as age, that could shape their views (Principi et al., Reference Principi, Fabbietti and Lamura2015).

In addition, there may be sector and organisational size differences. Research has shown that age stereotypes may be more pervasive in certain industries, e.g. finance, insurance, hospitality, retail and computing (Posthuma and Campion, Reference Posthuma and Campion2009). Certain sectors/industries in particular are associated with poor practice towards older workers (McNair and Flynn, Reference McNair and Flynn2006a, Reference Loretto and White2006b; Peters, Reference Peters2011; Martin et al., Reference Martin, Dymock, Billett and Johnson2014). While the construction sector has a high proportion of workers aged 55+, attitudes to older workers in the sector are mixed, with hazardous age discrimination practices identified in some businesses – although there are examples of good practice (McNair and Flynn, Reference McNair and Flynn2006a; Peters, Reference Peters2011). On the other hand, the health and social care sector generally has an older workforce, and there are largely positive attitudes to the older workforce, although hazardous practices may exist (McNair and Flynn, Reference McNair and Flynn2006b). There are also sectoral and occupational differences in terms of learning and training opportunities, and the value attached to the experience of older workers. For instance, in low-skilled retail jobs, older workers may be seen as not having the ‘right’ attitude, whereas in professional occupations, such as engineering, length of service is valued (Beck, Reference Beck2014). In terms of organisational size, examples of good practice in age management are often drawn from large supermarket chains, hospitality groups or utility companies – although there are exceptions (see e.g. Department for Work and Pensions, 2013). Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) face a specific set of issues when implementing age management policies and strategies. They may have fewer human and capital resources, less-formalised and strategic approaches, and fewer opportunities for flexible working (Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Rankine, Bell and MacVicar2007; Fuertes et al., Reference Fuertes, Egdell and McQuaid2013; Atkinson and Sandiford, Reference Atkinson and Sandiford2015).

It is in this context that the labour process perspective (Thompson, Reference Thompson1989; Thompson and Smith, Reference Thompson and Smith2009) theoretically influences this paper. Recent writing on employment is increasingly concerned with the rising ‘precarity’ of contemporary work, with a focus on the rising insecurity and ‘risks’ (Beck, Reference Beck1992) that are increasingly borne by the employee themselves (see Gill and Pratt, Reference Gill and Pratt2008). Labour process theory, a meso-level theoretical perspective originating in Marxist theory but largely independent of Marxism with the establishment of a ‘core’ theory (Thompson, Reference Thompson1989), asserts that employers purchase the employees’ potential to labour – or ‘labour power’ – and employers are therefore impelled to maximise the conversion of this potential to labour into profitable production (Thompson and Smith, Reference Thompson and Smith2009). Management therefore controls the work of labourers to reduce the ‘indeterminacy’ of this process. However, the research base outlined above indicates that employers may not be maximising the potential of the older workforce. Employers do not see the need to invest in, or adapt to, older workers. While much of labour process theory has focused on the various ways workers are controlled or the ways workers resist this control, little has been written on ageing and labour power from a labour process perspective. Age can be seen as essential to labour process analysis as it directly affects the capacities of embodied labour power and the potential value of this power in the labour market and for employers. While much has been written about the forms of labour power valorised within the labour process, such as manual, mental, emotional and aesthetic forms of labour power (see Witz et al., Reference Witz, Warhurst and Nickson2003; Thompson and Smith, Reference Thompson and Smith2009; Vincent, Reference Vincent2011), writing on how age itself is managed and profited from within the labour process perspective is currently neglected.

Method

This paper draws on qualitative research undertaken in Fife, Scotland in 2016. Fife is a council area in the east of Scotland, located between the Firth of Tay to the north and the Firth of Forth to the south. It is the third largest local authority area in Scotland by population. The 2015 population for Fife stood at 368,080, accounting for 6.9 per cent of the total population of Scotland (National Records of Scotland, 2017b). The Fife population is ageing. By 2039 the population of Fife is projected to increase by 5.4 per cent (from the base year of 2014), with the 75+ age group projected to increase the most in size, followed by the 65–74 age group (National Records of Scotland, 2017b). Life expectancy at birth has also increased in Fife (National Records of Scotland, 2017c) and the low fertility rate (1.66 in 2016) falls well below the replacement rate of 2.1 (National Records of Scotland, 2017a).

In terms of the characteristics of the Fife labour market, the largest employing industries in Fife in 2015 were: wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles; human health and social work activities; manufacturing; public administration and defence; compulsory social security; and education (Office for National Statistics, 2017). The Fife business base is dominated by SMEs. Of the 10,815 business sites, 68 per cent of sites employ one to four people, 15 per cent of sites employ five to nine people, 6 per cent of sites employ 10–14 people, 8 per cent of sites employ 15–49 people and 3 per cent of sites employ 50 or more people (Fife Council, 2015). The dominance of SMEs is of particular note given the specific set of issues faced by SMEs when implementing age management policies (Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Rankine, Bell and MacVicar2007; Fuertes et al., Reference Fuertes, Egdell and McQuaid2013; Atkinson and Sandiford, Reference Atkinson and Sandiford2015).

For the purpose of this research, ‘older workers’ were defined as those aged 50+ (Department for Work and Pensions, 2014). The authors do, however, acknowledge the difficulties and lack of clarity surrounding attempts to define the ‘older worker’, alongside the stigma and prejudice associated with the term (Desmette and Gaillard, Reference Desmette and Gaillard2008; van der Heijden et al., Reference Van der Heijden, Schalk and van Veldhoven2008; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Heraty, Cross and Cleveland2014; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Loretto, Marshall, Earl and Phillipson2016). Therefore, questions were asked to reveal understandings of what consitutes an older worker, not necessarily grounded on chronological age.

The sample

Six workplaces were recruited to take part in this qualitative research. Workplaces were identified through two main avenues. First, as part of a wider research project, an online survey of workplaces in Fife was conducted (this survey is not reported upon in this paper; for further details, see Egdell et al. Reference Egdell, Chen, Maclean and Raeside2017). Workplaces participating in the online survey were asked to indicate if they were happy to take part in interviews of managers and older workers. Second, in order that the workplaces taking part in the interviews represented the diversity of employers in Fife, employer databases and directories were mined to identify potential case study workplaces. The databases and directories drawn upon included the Financial Analysis Made Easy (FAME) database,Footnote 3 which the authors have access to through their university, and Fife Council's Business Directory.Footnote 4

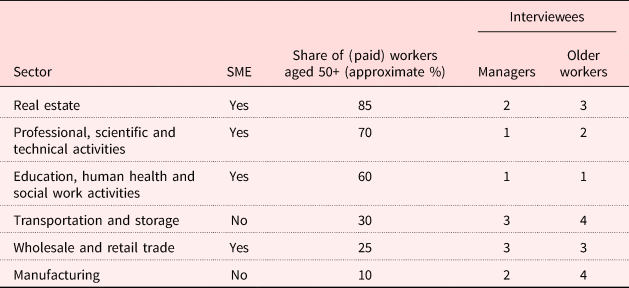

As detailed in Table 1, the six workplaces that participated represented a range of sectors and included SMEs and microenterprises (as defined by the European Commission 2017). In terms of the share of workers aged 50+, the proportion of older workers ranged from just over 10 per cent of the workforce to over 80 per cent. The proportion of older workers in these workplaces and/or the impact of the ageing population was expected to increase for a variety of reasons including low staff turnover and the rising State Pension age.

Table 1. The sample

Note: SME: small and medium-sized enterprise.

Overall, 29 individuals were interviewed. Those interviewed were selected by the key gatekeeper that the research team contacted to access the participating workplaces. These gatekeepers were usually the managing director/business owner or an HR manager. The research team requested that they speak to several individuals with managerial roles, as well as a number of employees aged 50+ . The numbers interviewed in each workplace depended on the size of the organisation.

Twelve individuals from the six workplaces who had managerial roles were interviewed. Their roles included managing director/business owner, HR manager, line/general manager and/or occupational health roles. In some instances, due to the size of the workplace, some of those interviewed occupied one or more of these roles. Throughout this paper, these participants are described as ‘managers’. In addition to the managers interviewed, 17 older workers (i.e. employees aged 50+), working in a range of roles in the participating workplaces, were interviewed. Throughout this paper, these participants are described as ‘older workers’.

It should be noted that some of the managers, incidentally during the course of the interviews, disclosed that they were aged 50+ . Consequently, their interview narratives to some extent reflected not only their managerial roles, but also their experiences as older workers. However, from the outset, the research design was to compare the views of managers and older workers. That some of the managers were also older workers is therefore treated as a coincidence. Thus, this paper does not report on a study of older workers irrespective of their position in the workplace hierarchy, but on a study of managers and older workers.

Data collection and analysis

The research team undertook workplace visits and conducted semi-structured interviews with managers and older workers. The interviews gathered information on attitudes and policies/practices towards older workers with a focus on workplace health, safety and wellbeing. Information was also gathered regarding opinions of the impact of demographic trends.

All interviews were audio recorded with the participants’ permission, and transcribed. Thematic analysis was applied to identify key themes in the data. An interpretivist approach was taken, not seeking to make generalisations to the wider population (Lin, Reference Lin1998). The research adhered to the Code of Practice on Research Integrity of Edinburgh Napier University. Written consent was taken from all participants. The data from the managers and older workers are presented in separate sub-sections, as the consent form detailed to the older workers that their data would be written up separately to that of the managers to help preserve their anonymity. Similarly, in order to preserve the anonymity of both managers and older workers, their specific role or the sector that they represented is not reported in the findings – although they were assigned randomly allocated interviewee numbers in order to highlight that quotations are taken from a range of participants.

Results

This section draws upon the interviews with the managers to examine how they think about age and ageing, as well as their priorities in terms of supporting older workers now and in the future. Then consideration of the key themes emerging from the interviews with the older workers is presented, revealing the lived experiences of age and ageing in the workplace.

How do managers think about age and ageing in the workplace?

‘Feeling’ older or ‘thinking’ older was cited in several instances as a key defining factor of an older worker, rather than the chronological age of the individual. While the Department for Work and Pensions (2014) defines an older worker as those aged 50+, older managers rejected the notion that they were ‘older’ or ‘too old’ to work, citing that they did not ‘feel’ older. The definition of an older worker depended on the individual in question. For example, one manager stated that, ‘I am [in my sixties] … but I am not considering myself old yet’ (Manager 12). Older workers were those who were ‘set in their ways’ and could not ‘adapt to change’:

I would say I would put somebody as older if they're thinking is older, they're more set in their ways. Rather than their actual age. (Manager 8)

In this context, the 50+ marker was not seen as relevant, as depending on the individual, someone in their forties could be considered an older worker because of their way of thinking. The sector or occupation that the individual worked in was also important when managers thought about age and ageing in the workplace, with experiences of age being seen as very different in physical roles and office-based (sedentary) roles. One manager commented that while someone may be able to work in an office, they may be ‘too old’ to do heavy manual work:

I would say that's a very strange question, [because] it depends on, what you're doing for a living. To have someone [doing heavy manual work] at the age of 75, you know, you're too old to do that. But if they're in the office … then they're fine. (Manager 5)

As such, even in one workplace where there was a variety of job functions, understandings of age and ageing could vary greatly.

Legislation was important in shaping the way in which age was thought about. Anti-discrimination legislation meant that managers could be reticent to identify workers in terms of their age: ‘We don't identify an older worker for obvious reasons as well, an age discrimination point of view’ (Manager 11). Many managers also felt that the changes in the legislation in relation to pensions and retirement had moved the ‘goalposts’ and changed the definition of an older worker. For example, one manager expressed that the removal of the DRA meant that the term older worker was no longer relevant:

It probably isn't as meaningful as it used to be because we all retired at 60, so if you got to 50 you were into single figures to retire. Now with no retirement age that doesn't really reflect an older worker now. (Manager 3)

It is interesting to note though, that managers still felt that older workers had a mind-set that they would retire at a certain fixed age, as it was what they had ‘psychologically planned’ (Manager 8). Others, examining how far current policy reforms are in line with the retirement age preferences of older workers, have highlighted that many still plan to retire before the ‘politically envisioned’ or ‘nationally defined’ retirement (Hofäcker, Reference Hofäcker2015). One manager, reflecting on their own situation, commented that they had previously felt that they were ‘always going to retire at 60’. This had been the status quo ‘until a few years ago when the government went hang on a minute, let's change the goalposts’ (Manager 3).

In some occupations, this moving of the goalposts was highlighted as having implications for the health and wellbeing of older workers. One manager stated that some of the workers in their workplace who were in their forties were signalling concerns that they could not keep working until they were in their late sixtiesFootnote 5 because of the physically demanding nature of their work. It could be suggested that previously workers ‘put up’ with physical demands because they knew that they could retire when they were 60–65 years. Having to stay in the workplace for longer made these demands less bearable, and the cumulative effects on the health and wellbeing of older workers was greater.

Questions were asked to explore the managers’ perceptions about the skills and abilities of older workers. The interviews revealed a range of sometimes complex and contradictory attitudes held by managers when thinking about age and ageing in the workplace, confirming existing research (Van Dalen et al., Reference Van Dalen, Henkens and Schippers2009; Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Chan, Snape and Redman2001; Dordoni and Argentero, Reference Dordoni and Argentero2015; Kroon et al., Reference Kroon, Van Selm, ter Hoeven and Vliegenthart2018). Examples from three workplaces were given where (new) technology had presented challenges to older workers. Some managers also felt that older workers were not willing to change ways of working and were reluctant to adapt to change. As one manager commented: ‘you will inevitably have some people who will say well this is the way I have always done it, so that's the way I am always going to do it’ (Manager 1). For this manager, being able to adapt was important given the pace of technological change. Questions therefore need to be asked regarding the ability of those (older and younger) workers who cannot adapt to new technology to stay engaged in the labour market given the increased digitalisation and technological transformation of the workplace (Störmer et al., Reference Störmer, Patscha, Prendergast, Daheim, Rhisiart, Glover and Beck2014).

The pace at, and way in, which older workers worked was also a concern for some managers. Older workers were perceived as being less able to work in fast-paced environments. One manager, reflecting on their own situation, stated that they would be unable to carry on working at this pace as they got older:

I have a very fast-paced, very reactive [job], if something happens I have to react to it. [Some days] I'm up at quarter past four in the morning, and I come back home at half past ten at night. Could I do that in a few years’ time? I don't know the answer to that, but I'm surmising possibly not, I wouldn't have the same energy. (Manager 3)

Other managers felt that older workers lacked attention to detail, and had increased risk aversion meaning that business opportunities could be lost. Some managers felt that harder physical work was not suitable for older workers, and some did equate ageing with an increased risk of illness and decreased physical abilities. It has been identified elsewhere that certain jobs or professions may be viewed as unsuitable for individuals of particular ages (Posthuma and Campion, Reference Posthuma and Campion2009).

Turning to the positive attributes of older workers, a range of advantages to employing older workers were mentioned, including bringing valuable life experience, skills, consistency and pragmatism to their work. They could act as mentors to younger workers, teaching them the ‘tricks of the trade’. Older workers were also felt by managers to be an asset as they could relate to an older client base. Some managers also stated that older workers had a better work ethic than younger workers: ‘I'd say older workers never, ever suffer from the Monday morning blues’ (Manager 5). The skills and abilities of older workers are often contrasted against those of their younger colleagues (Taylor and Earl, Reference Taylor and Earl2016).

Older workers were also felt to be more loyal in terms of being more likely to stay with an organisation for a longer period than younger colleagues. Many participants saw this as an advantage as it gave stability in the workplace. One manager, from a small company, described how younger workers often wanted to progress. The manager felt that older workers did not necessarily want to progress and were happy to stay in their role. In the industry this workplace was in, this meant that younger workers would go and set up their own company once they had been trained. The authors of this paper would argue that the size of the organisation could also play a role, with limited opportunities for younger workers to progress in SMEs, and therefore the need for them to set up their own company if they wanted a managerial position.

Arguably this stereotype about the ambitions of older workers could limit the opportunities for those older workers who wanted to progress. As previous research has found, opportunities for older workers to develop and progress may be limited (Beck, Reference Beck2014; Kroon et al., Reference Kroon, Van Selm, ter Hoeven and Vliegenthart2018). Another manager commented that they tended to promote younger workers:

I think the older they get out there, when you say you're doing a good job, I'm thinking of promoting you, they're quite happy doing what they're doing. The younger guys who were shown to be enthusiastic, yeah that's the guys that I tend to promote because I look at them as they are this company's future. (Manager 5)

The quotation draws attention to assumptions that might exist about the short length of tenure of older workers (Posthuma and Campion, Reference Posthuma and Campion2009). Younger workers who will stay on with the organisation are the future, rather than older workers who will only remain with an organisation for the short term. However, this can be contrasted with the views of other managers who felt that older workers gave stability in the workplace.

The quotation from Manager 5 also highlights the benevolence that managers may feel towards younger workers – especially in the context of high youth unemployment in the aftermath of the 2008 recession (Bell and Blanchflower, Reference Bell and Blanchflower2011) – as well as the need to think about the long-term sustainability of an organisation. In terms of performance, managers consistently tended to see older workers as reliable, consistent performers – in labour process terms, a reliable source of labour power – that required little managerial intervention. Younger workers were the ‘company's future’. Therefore, policies and practices towards older workers need to be understood as an intergenerational project for managers, who are also considering the needs of younger colleagues and the importance of succession planning.

The main priorities for employers in supporting older workers now and in the future

As outlined earlier, the overriding message from the managers was that they tended to think about employees in terms of the individual and their abilities rather than their age. This could, in part, explain why there was not much evidence that the suitability of the workplace for older workers had been considered. Managers from two workplaces felt that it was up to the employee to decide whether they were able to do their work – although in one case this was also verified by a medical examination. As such, it seems that managers are absolving themselves of any responsibility towards older workers. For employees, links can be made to Beck's (Reference Beck1992) risk thesis and the increased individualisation that can be observed in reflexive modernity. Yet, in terms of the labour process perspective, management is impelled to maximise the value produced from its purchase of labour power (Thompson, Reference Thompson1989; Thompson and Smith, Reference Thompson and Smith2009). Within this research, we can see that age management procedures are negligible for many workplaces because as long as workers continue to perform, there is no need to invest or adapt workplaces.

Some workplaces did have policies in place to manage the effects of an ageing workforce. One workplace operated a phased retirement scheme, another had developed a scheme to support succession planning and knowledge retention as older workers retired. However, in the main, the majority of workplaces did not have specific policies in place to manage the needs of older workers, and it was not felt that there was a need to adapt the workplace:

I can't see anything we would need to adapt or change. That might change as the years go on, and so, at the moment I would say no. (Manager 9)

In part, these views may be the result of the approach described above where employees were considered in terms of their abilities rather than their age. Another consideration is that some workplaces were small and did not have HR departments, or similar, to develop and implement policies (Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Rankine, Bell and MacVicar2007; Atkinson and Sandiford, Reference Atkinson and Sandiford2015; Fuertes et al., Reference Fuertes, Egdell and McQuaid2013). This perhaps points to the importance of local authorities and sector bodies working with SMEs to give them the HR and health and safety support necessary to meet the needs of their older workers. For example, in Scotland support is available to SMEs through Business Gateway, Healthy Working Lives and Fit for Work Scotland.

Because of this lack of policy, employee needs and adaption requirements were dealt with on an individual basis – whether it be an older worker or a younger worker. It was recognised that older workers might want to work more flexibly, decrease their pace of working or reduce their working hours in the run-up to retirement. In most workplaces there were opportunities for flexible working and adapting to the changing needs of an employee (whatever their age). One manager stated that:

If it suits them and it suits us then they can flex pretty much whenever they want to … as things change, and your circumstances change … we try and allow that. (Manager 12)

Workplaces whose work involved physically demanding tasks had mechanisms in place to monitor the health of their workers of all ages. However, in terms of flexibility in roles, managers did not necessarily feel that there were many options available.

The lived experiences of ageing in the workplace

We now turn to consider the interviews with the older workers, revealing the lived experiences of age and ageing in the workplace. The majority of the older workers tended to define ‘older workers’ as being aged 60+, with many of their comments linked to those who worked beyond the State Pension age. Thus, most of the older workers rejected the notion that they were ‘older’, citing that they did not ‘feel’ older and that the definition of an older worker depended on the individual in question.

It's difficult to answer that! Anyone over 60 I think, or 65. I think it's because that's always been classed as retirement, not now, but in the past. (Older worker 3)

There was some acknowledgement that others might perceive them to be older (for instance, the members of the research team who were interviewing them). The older workers also supported the assertions made by their managers that the age at which an individual ‘became’ an older worker had changed over time. The older workers in particular contrasted the current status quo with their experiences from when they were younger. For example, one older worker commented that when they were younger ‘someone [who] was in their fifties they were old’ but this had changed with the government changing the retirement age, so ‘people see you maybe in your late sixties as old’. In addition, as has been argued elsewhere, increasing life expectancies have challenged conceptions of age (Moulaert and Biggs, Reference Moulaert and Biggs2012).

The participants mentioned that either they themselves, or their colleagues, would seek to carry on working as long as possible. Sometimes there was a financial need to carry on working. Despite policy narratives about increasing the options available to older workers and providing fairness across generations (see e.g. Department for Work and Pensions, 2017a, 2017b), many do not have the choice but to continue working because of financial reasons. Historically, the percentage of pensioners on low incomes (before housing costs) has been much higher than for other groups – although the proportion of pensioners living in poverty has fallen over the last 50 years (McGuinness, Reference McGuinness2016: 16). Aside from financial necessity, the enjoyment of working was a driving factor for the older workers participating in this research to continue working – although there might be a desire to work more flexibly in future. Generally, the older workers consistently cited a high degree of commitment to and enjoyment from their work. Indeed, the majority of older workers all restated the importance of work throughout their interviews.

While physical limitations were overwhelmingly highlighted as a key barrier to continued labour market participation, a number of office-based older workers also cited mental barriers in terms of stress and pace of working. Some felt that they were ‘slowing down’, taking longer to complete certain tasks, feeling increasingly tired, and/or were unable or unwilling to work at a fast pace or in such a pressured way:

A lot of people, myself included, I have slowed down compared to the young ones. I can still do the job but I am a bit slower. (Older worker 10)

As was the case with the managers, the older workers were generally positive about the skills and abilities of older workers. Echoing the same views as their managers, the older workers felt that their workplaces did not need to adapt to accommodate older workers. However, the interviews with older workers revealed that in several workplaces, supervisors or older workers themselves had devised strategies to manage physical and mental limitations associated with ageing. It could be argued that the financial need for some older workers to carry on working, along with the difficulties faced by older age groups in finding work (Axelrad and James, Reference Axelrad, James, Antoniou, Burke and Cooper2016), could make older workers reluctant to request changes to their workplace. They may however, need changes to be made, as demonstrated by the informal strategies adopted that were effectively ‘self-managed’ processes that operated outside established workplace policies. One of the older workers described how they managed their workload to combat stress. Other examples observed within the research included rotating physical jobs, putting people on to lighter duties, and pairing of older and younger workers. Supervisors would determine which older workers would benefit from less-strenuous activities. These self-managed processes would not necessarily operate during periods of high service demand, with the older workers expected to work at the same rate as younger workers. Many of the older workers argued that the younger workers would eventually benefit from these strategies.

Discussion and conclusion

In the UK and internationally, increasing numbers of older workers are remaining in work (Aliaj et al., Reference Aliaj, Flawinne, Jousten, Perelman and Shi2016). Government has sought to encourage the continued labour market participation of older workers through removal of the DRA, the raising of the State Pension age and developing the awareness of the benefits of employing older workers amongst the business community (HM Government, 2011, 2014; Altmann, Reference Altmann2015; Department for Work and Pensions, 2017b). Despite this, the research base has consistently demonstrated that organisations are failing to prepare for and benefit from demographic and labour market changes, and that the business case approach to support the extension of working lives has not had the impact envisaged (Taylor and Walker, Reference Taylor and Walker1998; Flynn, Reference Flynn2010; Fuertes et al., Reference Fuertes, Egdell and McQuaid2013). Even if employers are developing policies to support their older workers, these are not necessarily translated on the ground (Loretto and White, Reference Loretto and White2006a, Reference Loretto and White2006b; Boehm et al., Reference Boehm, Schröder, Kunze, Field, Burke and Cooper2013). This paper has drawn on qualitative research undertaken with managers and older workers in Scotland to examine how they think about age and ageing in the workplace, the support put in place for older workers now and going forward, and the lived experiences of the older workers.

Previous research has highlighted a range of positive stereotypes that may be held by employers in relation to older workers, e.g. they are highly skilled and have a good attitude (Krings et al., Reference Krings, Sczesny and Kluge2011; Zheltoukhova and Baczor, Reference Zheltoukhova and Baczor2016). The findings of this current research confirm many of the positive stereotypes previously identified. The managers were generally positive about the skills and abilities of older workers. Compared to other countries (Greece, Spain and the Netherlands), UK employers may make more efforts to retain older workers and are more likely to see older workers as valuable workers (Van Dalen et al., Reference Van Dalen, Henkens and Schippers2009). This can be attributed to an employer attitude that ‘older workers are a fact of life – and you had better get used to that!’ (Van Dalen et al., Reference Van Dalen, Henkens and Schippers2009: 58). Indeed, in the participating workplaces, it was accepted that the proportion of older workers would increase. While ensuring that employers are aware of the benefits that older workers can bring to the workplace, it is important, however, not to fall back on normative stereotypes that could be harmful to those older workers who do not ‘conform’, as well as ageist assumptions about both older and younger workers that ‘pitch’ generations against each other (Taylor and Earl, Reference Taylor and Earl2016). While being positive, care still needs to be taken to avoid a ‘lumping together of older workers’ (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Dymock, Billett and Johnson2014: 1009).

Arguably, the overriding message from the research that warrants most attention is that managers tend to think about employees in terms of the individuals rather than their age. The older workers expressed similar views. Thus, it can be argued that managers and older workers do not think about age and ageing in the workplace, as it is not seen to be a relevant issue, despite the demographic trends. There was a lack of consensus about who ‘older workers’ are. There was no accepted chronological age. The DRA, which potentially provided a marker, was no longer relevant. Numerous and often contrasting views about the skills and abilities of older workers were highlighted.

On the one hand, adopting a subjective view of age and ageing presents opportunities for responsive and tailored support for employees. On the other hand, not considering the implications of age and ageing on the workplace may mean that support is not put in place to support workers as they get older.

The interviews with both managers and older workers demonstrated that the ageing workforce has not yet been effectively addressed through the development or review of workplace policies and practices. While managers were aware that the ageing population would affect their workforce, they had not considered the suitability of the workplace for older workers. Few of the participating managers believed that the ageing of the population would require changes to policies, practices and procedures. Some of the older workers themselves also agreed with these sentiments. Therefore, it could be argued that any adaptations that are made will be reactive, rather than proactive or preventative. Consideration, therefore, needs to be given as to potential effects this reactive approach could have on employee health and wellbeing. In two workplaces examples were given of practices to manage the effects of an ageing workforce (phased retirement and succession planning). It is, however, difficult to gauge whether these practices can be understood as efforts made by employers to ensure that they retain (tacit) knowledge and experience, or as efforts to meet the needs of older workers.

In some cases, managers felt that it was up to the individual older worker to judge whether they were able to continue working. Thus, it can be argued that managers are absolving themselves of any responsibility towards older workers. In part, it could be suggested that this state of affairs can be attributed to the legislative environment, which has sought to remove barriers to older workers, tackle age discrimination and make age less relevant in the workplace (see e.g. HM Government, 2011, 2014; Altmann, Reference Altmann2015; Department for Work and Pensions, 2017b). As the findings from this research highlight, one consequence of this is that the management of older workers is now fraught with ambiguity and the definition of ‘older worker’ has shifted alongside policy developments in how retirement is defined. It is hard to pin down exactly who older workers are as this may vary from individual to individual, by sector and by job role. Thus, the authors would suggest that employers may feel that it is hard, or not even relevant, to develop policies to support older workers if the legislation suggests that chronological age is not important. As others have found, there was a lack of ‘age awareness or strategies to integrate workers of different ages’ (Brooke and Taylor, Reference Brooke and Taylor2005: 426).

The views expressed by older workers also point to the complexities of managing an ageing workforce. While many felt that their workplaces did not need to adapt to accommodate them, some also expressed that they may need support to maintain their physical and mental health. As revealed in the older worker interviews, informal strategies to manage negative impacts of physically strenuous work or the negative effects of stress on mental health were formed by the workers themselves. Consideration needs to be given as to whether the presence of these practices points to the need to develop official policy and practice. While these informal practices could indicate at some level that the participating workplaces were ‘age friendly’ and ‘age aware’, they are very fragile arrangements and equitable and transparent implementation may not be guaranteed, especially as the workforce ages. The authors of this paper would also add that while advances in technology and ergonomic design of workplaces may reduce the negative health effects of some jobs (Hedge, Reference Hedge2017), the cumulative nature of ‘wear and tear’ to the bodies of older workers should not be underestimated. Therefore, remaining in the workplace may still present physical challenges to older workers because of the physical strain experienced earlier in working life when ergonomic design was less of a concern.

The experience of older workers in this paper can be seen in two ways. The individualised experience of age management for employees can arguably be seen in terms Beck's (Reference Beck1992) ‘risk’ thesis, with employers increasingly resistant to managing the responsibilities of older workers. Yet, the labour process perspective can help clarify this further. The focus on treating employees’ age and physical fitness for work on an individual basis, rather than having formal plans to manage the workplace for older workers, indicates a hands-off approach from management. While labour is performing and producing productively, employers do not need to provide significant adaptations to ensure that the embodied labour power of older workers is profitably exploited in the longer term. This reflects a lack of investment in older employees that has been demonstrated in previous research, particularly where older workers miss out on development opportunities because they are seen to provide a mentoring role to other employees (Kroon et al., Reference Kroon, Van Selm, ter Hoeven and Vliegenthart2018). Indeed, the socialisation practices in place and informal means of managing age within the organisations provide extra forms of unpaid labour that help employers ensure that the ‘indeterminacy’ of younger workers’ labour power is reduced and that it can be effectively exploited in the future.

As has been argued by Martin et al. (Reference Martin, Dymock, Billett and Johnson2014: 1011), ‘the challenge is to address the passive and widely held belief that workplaces are neutral places and have managers consider age in both their policies and practices’. A number of authors argue that supporting older workers necessitates a flexible and creative approach to policy and practice that acknowledges the heterogeneity of ‘older workers’ (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Dymock, Billett and Johnson2014). While in this current research the experiences of different groups of older workers (e.g. older women) has not been explored, the lack of age awareness identified does suggest that the specific needs of different groups of older workers need to be considered, otherwise they may be overlooked. As has been argued elsewhere in relation to older women workers:

the risk with this ‘flexibility for all’ approach is that it potentially overlooks the needs of specific groups of workers … a lack of employer policy that targets older women workers may compound their vulnerability as an employee group and, perversely, increase the risk of their early exit from the workforce. (Earl and Taylor, Reference Earl and Taylor2015: 218)

There are research limitations that need to be acknowledged. The sample size was small and located in one local authority area of Scotland. Therefore, the diversity of policies, practices and attitudes may not be revealed; and the specificities of experience in one geographical area may not be accounted for. Consequently, further research involving a larger sample across a wider geography is required. The reliance on gatekeepers to select those who were interviewed could mean that only those who would be ‘in-line’ with organisational rhetoric participated. Some might argue that this explains why, in some instances, the older worker responses echoed managers’ views. While it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about this either way, it should be noted that participants expressed both positive and negative views about their workplace. It was also beyond the scope of the research to unpick variation in experiences of different groups of older workers, e.g. older women and older workers from minority ethnic backgrounds. As a result of the study design, the age of the managers could not be considered in the analysis. Therefore, conclusions cannot be made regarding whether the age of the managers shaped attitudes towards older workers.

Further research would be useful in a number of areas. The small sample size makes it difficult to identify whether the demographics of each workplace have a bearing on the attitudes of managers and employees as to whether the ageing of the population is something that warrants attention. If the majority of the workforce is older, does this mean that older workers are more likely to be seen as a ‘non-issue’ because this is the norm in the organisation? Fuertes et al. (Reference Fuertes, Egdell and McQuaid2013) draw attention to the benefits of age management awareness interventions in influencing employer attitudes and practices towards older workers. Given that the workplaces did not consider population ageing to be of real concern, it would be interesting to revisit the participating workplaces to see if taking part in the research had subsequently changed their views. Had engaging in a process that raised questions not previously thought about subsequently altered the views of both managers and older workers? Further research with a larger sample of workplaces would also be useful in terms of exploring any variations that might be present in terms of policy, practice and attitudes between different-sized organisations and different sectors. Due to its scope, the paper can only provide a few indications in terms of sector-specific issues, e.g. in terms of the lack of flexibility available to those older workers in physically demanding roles; as well as findings across different-sized organisations in terms of lack of consideration of the need to support older workers specifically. It was also beyond the scope of this paper to unpick and analyse critically the quite ageist sentiments expressed by some participants.

This research has indicated that legislation to remove barriers to the extension of working lives has meant that older workers are not necessarily being supported by their employers. Managers are taking an age-neutral approach to the management of their workforce and do not see the need to act, even if they acknowledge that their workforce is ageing. From a labour process perspective, while labour is performing and producing productively, managers do not see the need to make adaptations to ensure that the labour power of older workers is profitably exploited. While older workers do not feel that workplaces need to adapt to accommodate them, there is evidence to suggest that they are also enacting informal practices to support an ageing workforce. As increasing numbers of older workers have no choice but to remain in work, and, as focus is increasingly placed on the importance of fair and decent work (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Marsh, Nicol and Broadbent2017), age awareness will need to increase to support the diverse workforce, foster intergenerational relations and tackle attitudes that present barriers to older workers.

Acknowledgements

This paper draws on research carried out for the Workplace Team, Health Promotion, Fife Health and Social Care Partnership, and Fife Health and Wellbeing Alliance by the Employment Research Institute at Edinburgh Napier University. The analysis reflects the views of the authors alone. We would like to thank all those who gave their time to participate in this research. We would also like to thank Dr Helen Graham and Dr Vanesa Fuertes (formerly of the Employment Research Institute at Edinburgh Napier University) who conducted and transcribed some of the research interviews.

Ethical standards

An ethics checklist was completed through Edinburgh Napier University's research management system when preparing the application for funding. This checklist was approved by the Edinburgh Napier University Business School ethics approver. A full application to Edinburgh Napier University Business School Research Integrity Committee for ethical approval was not required.