Introduction

At the height of the Nigeria-Biafra war in 1968, about 4,000 Biafran children were evacuated and flown to the neighboring countries of Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire by relief agencies to protect them from the conflict. This was part of a concerted international humanitarian airlift operation that brought much-needed food, medicine, and other supplies to the besieged Biafra territory. At the end of the war three years later, most of the children were returned to their homes in Nigeria through an international humanitarian repatriation effort. The process of evacuation and repatriation was complicated by wartime hostilities, national interests, and the politics of international humanitarian interventionism. Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire were two of only four African countries that recognized secessionist Biafra, putting both countries at odds with Nigeria’s federal government, which insisted that the evacuated children were not “refugees” but rather “temporary evacuees.” Eager to have the children returned after the war, the government of Nigeria solicited the intervention of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) to assist with their repatriation. The governments of Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire considered the Biafran children to be their responsibility while they were within their borders and were reluctant to accept the involvement of international agencies. The government of Gabon considered the repatriation of the children to be “abduction” (The Star 1970). When the UNHCR eventually became involved, it had to carefully navigate the politics of classifying the children, describing them as “evacuees” or “Nigerian children” rather than as “Biafran refugees.”

This article examines the politics of international humanitarianism in the wartime evacuation and repatriation of Biafran children during a period when the UNHCR’s refugee protection policies and procedures were still being formulated. There are two main arguments. The first argument is that the UNHCR’s role in the repatriation of Biafran children marked a pivotal moment in the agency’s expansion from its Eurocentric origins into Africa and the global South. UNHCR officials recognized this at the time of this event. Commenting on the role of the agency in the repatriation operation in 1971, one senior UNHCR official stated: “There is no doubt that this operation, of which the full story still has to be written up, will go down as one of the most impressive chapters in the annals of the UNHCR” (UNHCR Archives [hereafter UNHCRA] 11/1/61-610.GEN, NIG, UC.4 [R1]). Yet, this key episode in the early history of UNHCR has been largely overlooked in studies of the agency and in histories of international humanitarianism in the twentieth century.Footnote 1 By drawing attention to this episode in the Nigerian civil war, this article responds to calls for histories of the early period of UNHCR that can be used to address today’s humanitarian and refugee crisis (Loescher et al. Reference Loescher, Betts and Milner2017:77). The Biafran repatriation is also important because it highlights how the UNHCR’s activities in Africa have shaped the development of international humanitarianism.

The second argument is that the Biafran repatriation operation offers useful insights into the politics of classifying displacement in international humanitarianism. Specifically, I am interested in what has been described as the politics of naming conflicts and classifying the victims of conflicts (Mamdani Reference Mamdani2017:5–8; Berry Reference Berry2016). In the case of the Nigeria-Biafra war, who named the conflict? How were parties in the conflict categorized, and what difference did it make? In this case, who got to be labeled as a refugee, displaced person, evacuee, or simply a forced migrant? The politics of classifying victims and displaced persons extended to the broader framing of the Biafran conflict. There is considerable semantic and political difference between labeling the conflict as an “insurgency,” as the Nigerian federal government did, a “civil war” as the international media did, and a “genocide” as the Biafrans did (Moses & Heerten Reference Moses and Heerten2018:5).

More recent debates on the politics of naming conflicts have centered on the creation of “hierarchies of victimhood,” as evident in the mobilization of international humanitarian interventionism in the Darfur “genocide” but not in comparable atrocities and suffering in Iraq or Bosnia (Mamdani Reference Mamdani2017). Within refugee studies, the politics of categorizing migrants holds contemporary relevance to current debates in Europe, the United States, and elsewhere about limiting migrant flows (Schoenholtz Reference Schoenholtz2015:83). In these situations, the politics of naming has centered on efforts to distinguish between “genuine refugees” and other forced, voluntary, or “economic” migrants. In line with the call for new approaches to refugee studies that question dominant discourses and interrogate narrative authority and historical agency, this article explores how state interests and wartime politics of international humanitarian interventionism have shaped the discourse of displacement and the protection of unaccompanied children—the most vulnerable victims of the conflict.

The Legacy of “Biafran Babies”

In 2015, Gabon was embroiled in a controversy over the nationality of its president Ali Bongo Ondimba. The rumor was that Ali Bongo was not a Gabonese and was not born in Gabon. Critics claimed that Ali Bongo, who succeeded his father’s 40-year rule of the country, was in fact a Nigerian, one of the 4,000 Biafran children evacuated from Nigeria during the Nigerian-Biafra war in 1968. As the story went, the former President Omer Bongo adopted the young Ali from among the starving Biafran children evacuated to Libreville by humanitarian agencies to protect them from the conflict. Photographs made the rounds on social media purportedly showing Ali as a child among a group of malnourished Biafran children newly arrived in Libreville. In Nigeria, the story of Ali Bongo’s alleged Nigerian ancestry resonated with a resurgent Biafran separatist movement (PM News 2015). The apparent origin of the story was a French writer whose claims in a book on Ali Bongo’s rule led opposition politicians to demand a DNA test from the president. This claim was politically sensitive because it disputed Ali Bongo’s qualification to be president under Gabon’s constitution (Jabbar & Ofiaja Reference Jabbar and Ofiaja2014). Gabonese officials denounced the rumors as unfounded, insisting that the President was born in Gabon. The controversy over President Ali Bongo’s alleged Nigerian ancestry brought renewed public attention to the largely forgotten episode of Biafran children airlifted out of Nigeria during the civil war and the fate of some of the children who were never reunited with their families.

The memory of Biafran refugee children evacuated during the war has more recently been revived by a renewed scholarly interest in the history of the war and the rise of pro-Biafra political activism in Nigeria and the Igbo diaspora (Omaka Reference Omaka2016; Moses & Heerten Reference Moses and Heerten2018; Heerten Reference Heerten2017; Bird & Ottanelli Reference Bird and Ottanelli2017). Resurgent Igbo separatist movements such as the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB) have drawn attention to this episode to promote Igbo nationalism and their campaign for the recreation of an independent state of Biafra (Okonta Reference Okonta, Moses and Heerten2018:364). Recent studies have also drawn attention to the plight of Biafran mothers who had to make the difficult decision to give up their sick and malnourished children who were subsequently evacuated. For some of those women, such painful separations were final, as they were never reunited with their children (Chukwu Reference Chukwu, Moses and Heerten2018; Ibeanu Reference Ibeanu, Osaghae, Onwudiwe and Suberu2002). The episode of the evacuated Biafran children has also been kept alive by Igbo cultural groups committed to identifying and reuniting the Biafra children, now adults, with their families in the former conflict areas. Their aim is to identify all the children taken to relief camps by the Biafra humanitarian airlift relief program and bring closure to their families by locating burial sites of children who did not survive in the relief camps, through forensic investigations and DNA analyses (Igbo League N.D.).

Blockade and Airlift

The Nigerian civil war broke out in 1967, just seven years after the country gained independence from Britain. What began as a “police action” by the federal government to rein in an insurgency in the Eastern part of the country quickly escalated into a civil war described at the time as one of the most significant global humanitarian crises of the post-World War II era (Neue Zürcher Zeitung 1969). The ethnic Igbo of Eastern Nigeria, who felt marginalized and threatened within the new nation, fought to establish an independent Biafran state. Nigeria’s leaders, on the other hand, saw the conflict as a war to uphold the unity and territorial integrity of the newly independent country. Biafran leaders accused the Nigerian government of waging a genocidal war of starvation against the Igbo people, an allegation that elicited global concern. Images of starving Biafra children horrified many people around the world, prompting an international humanitarian campaign to provide food and medical supplies to the conflict areas. The fundamental question raised by the Nigerian civil war in the post-colonial era of the right to self-determination was whether there existed a threshold of state repression beyond which a people have the right to create another state to ensure their protection (Simpson Reference Simpson2014:342).

Unlike other Cold-War era “Third World” conflicts, international intervention in the Biafran war resulted primarily from humanitarian rather than political or ideological concerns (Stremlau Reference Stremlau2015:xi). There were, however, implicit political considerations in the ways various countries approached this humanitarian aid. While the suffering was hardly unprecedented, the international response to it was (Barnett Reference Barnett2013:133). The war contributed to the rise of post-colonial moral interventionism. It also ushered in a new form of human rights politics, one that “first emerged in the humanitarian mission stations and hospitals of Biafra and took full shape in the post-Cold War era of humanitarian interventionism” (Heerten Reference Heerten2017:337).

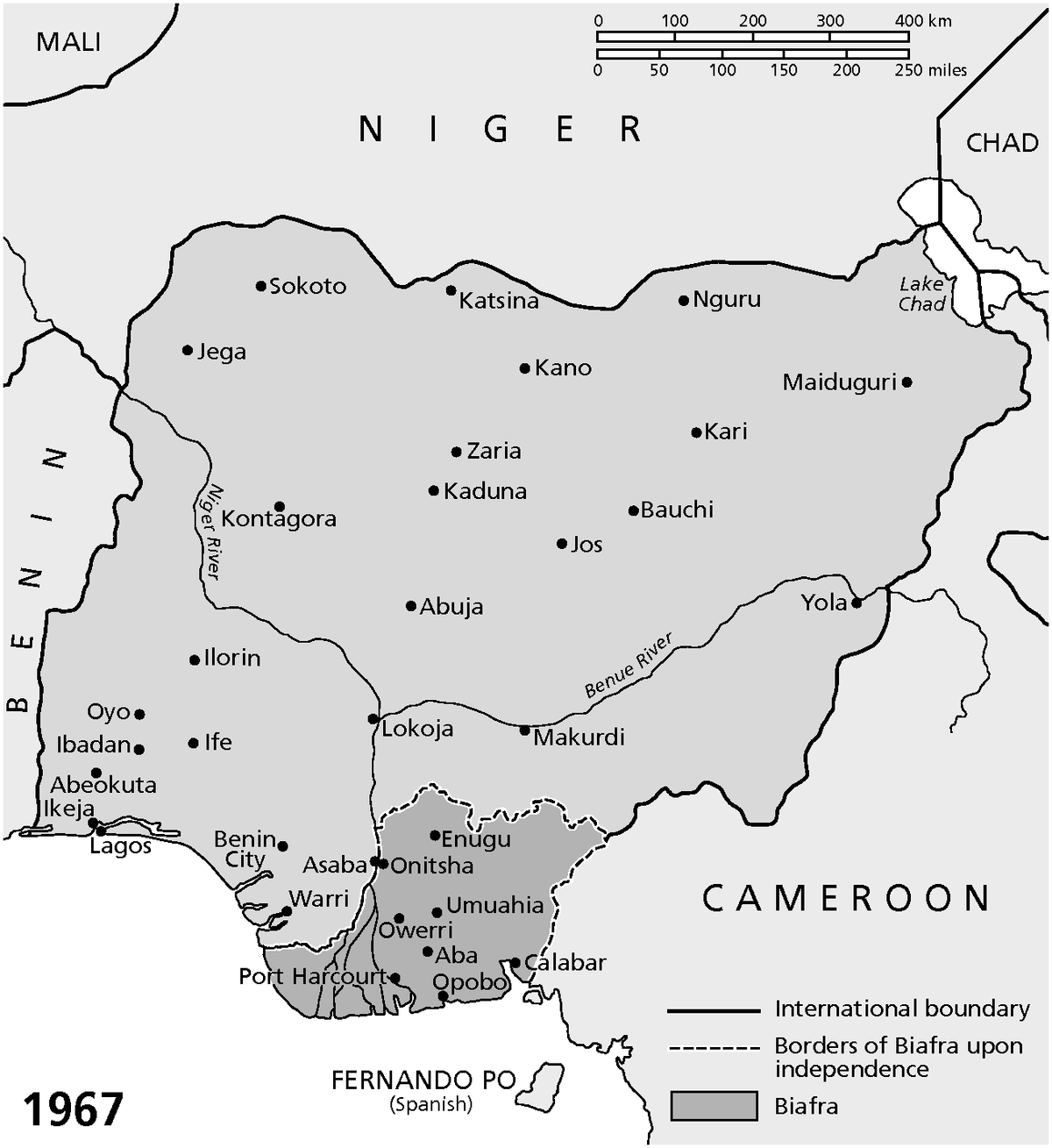

During the conflict, mass starvation became an instrument of war. As part of its military strategy to defeat the secessionist Biafra, the federal government imposed a blockade of all air, sea, and land routes into and out of Biafra territories, effectively cutting Biafra off from the rest of the world (see Figure 1). The blockade stopped food and medicines from getting into Biafran territories, which were already devastated by the war. Although international relief agencies such as the Red Cross and Oxfam International and Christian charity groups such as Caritas Internationalis and the Joint Church Aid were eager to provide humanitarian support, the Nigerian government did not welcome these interventions. Nigerian officials presented the conflict as a domestic matter that should be fully under its control. As the head of state Yakubu Gowon stressed, “I regard this as a Nigerian problem to be solved by Nigerians” (quoted in Gribbin Reference Gribbin1973:52). In contrast, the Biafran head of state, General Ojukwu, made repeated appeals to the world’s humanitarian agencies to come to the aid of the people of Biafra (Igwe Reference Igwe1969).

Figure 1. Map of Nigeria showing Biafran territories

Biafran war propaganda and independent reports from missionaries and humanitarian organizations working in the conflict zone painted a picture of mass starvation and civilian mortality that galvanized sustained international humanitarian relief efforts. By the end of the war in January 1970, about one million people were estimated to have died of malnutrition, starvation, and related diseases (Omaka Reference Omaka2016:62). Protein deficiency was the biggest problem, as the population of fourteen million in Biafran territories were denied access to protein-rich foods, such as imported fish, beef, beans, and peanuts traditionally supplied from Northern Nigeria. Food scarcity also meant that children, who are most susceptible to hunger and diseases, were the first victims of the blockade.

It is estimated that within the first year of the war, three thousand people—mostly children and the elderly—died daily from protein deficiency and starvation (Waugh & Cronjé Reference Waugh and Cronjé1969:67). By December 1968, more than five hundred thousand Biafrans had died of starvation and disease. Many of these victims were children. The prevalence of kwashiorkor and marasmus (general undernourishment), the diseases that made the war infamous, intensified global calls for international intervention and humanitarian aid (British National Archives DO 186/1; De St Jorre Reference De St. Jorre1972:237–38). By the summer of 1968, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC /Red Cross) reported that three million children were near death. Similar assessments by the International Social Service (ISS), and the International Union for Child Welfare (IUCW), following missions to the conflict areas in 1970, estimated that there were 30,000 vulnerable displaced children inside Nigeria. These missions recommended that the children should urgently be accommodated in the receiving centers in transition to more permanent safe placement (Goetz Reference Goetz2001:4–5).

In the age of audiovisual mass media, the internationalization of this “Third World” conflict was dependent on images of suffering. Media reports and images of malnutrition and mass starvation in Biafra galvanized humanitarian efforts to send critical food and medical supplies to Biafra and for affected children in the conflict areas to be evacuated from Nigeria. Television brought the war home to a global audience, with images of Biafra’s starving children brought to the living rooms of many people in Europe and North America who in a previous era would have been less informed about such humanitarian crises happening on the other side of the world. The publication of disturbing images of the starving “Biafran babies,” which would become an icon of Third World misery, was the defining moment that turned the conflict into a global media event (The Times 1969). In what has been described as the “post-colonial politics of pity,” Biafra was framed more as a humanitarian rather than a political cause, in which children became the visible face of the suffering (Heerten Reference Heerten2017:9,152).

Many sympathizers saw similarities between the images of starving Biafran children and the images of starving Jews and other prisoners in Nazi concentration camps during World War II. This gave rise to several new activist groups. Biafran support committees mushroomed in the West to raise funds for relief operations and to lobby Western governments to intervene in the conflict. The humanitarian crisis also galvanized a broad coalition of established international non-governmental organizations into action, including the ICRC, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Oxfam International, Caritas Internationalis, World Food Programme (WFP), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), World Council of Churches (WCC), and the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). The work of these organizations was made possible by an unprecedented outpouring of private donations that surprised relief workers (Teltsch Reference Teltsch1969a:30).

ICRC officials in Nigeria who, by the middle of 1968, had estimated that 3,000 famine deaths occurred daily in Biafra, recommended a massive airlift of relief supplies as the only viable solution. Despite strong objections from the Nigerian government and actions by the Nigerian army to prevent aid provision, the ICRC and other relief agencies began covert airlift missions to provide supplies to the people of Biafra. The ICRC would later restrict its activities to supporting the Nigerian Red Cross, following objections from the Nigerian government. The airlift mostly comprised secret missions taken in the dark of night in an effort to evade the Nigerian military, which routinely targeted aircraft and airfields with bombing. The Biafran airlift remains one of the largest civilian airlifts, and like the Berlin airlift of 1948–49, one of the largest non-combatant airlifts of any kind. Although other countries were reluctant to participate directly in the airlifts into Biafra due to the politically sensitive nature of the conflict, Gabon, Dahomey (Benin), Portugal, and Equatorial Guinea supplied the external bases. Governments such as the United States, Canada, Norway, and Denmark provided food, medicine, and aircraft to Joint Church Aid and Canairelief to support the humanitarian airlift. However, such government participation was limited and was mostly a response to domestic pressure groups rather than an exercise in global responsibility (Gribbin Reference Gribbin1973:51).

Significantly, the Biafran airlift operations also involved the evacuation of many unaccompanied children from the war zone. Beginning in August 1968, a group of unaccompanied children was evacuated and flown away to Libreville (Gabon) by the Christian charity group Caritas Internationalis. The French and Biafran Red Cross, the Order of Malta, and the French organization “Terre des Hommes” also evacuated children to Gabon, Côte d’Ivoire, and São Tomé. The children were flown out of the war zones in the same planes that international relief organizations had flown clandestinely into Biafra with supplies. The goal of the evacuation was to remove the most vulnerable children from the war zones to safety, where they could be provided with nourishment and medical treatment. The Gabonese government, which recognized Biafra, welcomed the evacuation and indicated its willingness to host as many as two million children if shelter and care were provided by others. Provisioning for Biafran children evacuees became a key fundraising goal for relief agencies working in Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire. They embarked on fundraising campaigns in Europe and North America to build facilities and secure food and medical supplies for the evacuated children (Teltsch Reference Teltsch1968a:4, Reference Teltsch1968b, Reference Teltsch1969a). One relief worker involved in the airlift operation described the children and the evacuation process. The children were

in the last stages of starvation: limp bones, distended bellies, skeletal faces, large eyes. I looked down at the children, unable to place the sight in any context I had ever known. I had seen pictures of the starving Biafran children, and I had seen the recovering children on São Tomé, but this was something beyond all else. Vacant eyes stared at the vacant sky… We carried them up the ladder one by one. They were so very light. Soldiers, grim and silent, permitted a small-small light as we lifted our delicate cargo into the plane. We folded blankets on the floor and placed the children on them.

(Koren Reference Koren2016:231)By mid-1969, 3,940 Biafran children had been evacuated to Gabon, 908 to Côte d’Ivoire and 130 to São Tomé. The children evacuated to São Tomé were later moved to join others in Gabon. Most of the children airlifted out of the conflict zone to Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire were sent to hospitals, orphanages, and relief camps run by local and international humanitarian NGOs. In Gabon, 250 of the injured children ended up in a French military tent hospital in the Gabonese capital of Libreville (Howe Reference Howe1970:2). With the end of the war in January 1970, most of these children were brought back to Nigeria, and many of them were reunited with their families. Of about 5,000 children identified by UNHCR in Gabon, Côte d’Ivoire and São Tomé, about 4,000 had enough identifying information to be returned to their parents, relatives, or foster parents. The remaining 1,000 remained in their adopted countries. The largely forgotten wartime evacuation of Biafran children has been compared to the evacuation of Jewish children from Germany to other parts of Europe to escape Nazi persecution (Steinbeck Reference Steinbeck1993:12).

The Politics of Classifying Displacement

Since its establishment in 1950, one of the issues that has confronted the UNHCR is outlining a coherent and efficient process of determining who qualifies as a refugee, thereby deserving of international protection. Working with governments and other stakeholders, the UNHCR has, over the years, developed a comprehensive Refugee Statues Determination (RSD) process (UNHCR 2017b; Bianchini Reference Bianchini2010:368). This provides the legal and administrative framework for determining when a person seeking international protection may be considered a refugee under international, regional, or national law (UNHCR 1997).Footnote 2 A central consideration in the determination process is whether migrants are fleeing their home countries because of persecution, war, or violence, or whether they have “a founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group” (UNHCR 1951). While the understanding of how to determine refugee status via international law is a source of ongoing global contestation, at the time of the Biafran crisis this framework was not nearly as well established as it is today. As such, there was much uncertainty over the status of the evacuated Biafran children and the obligations of the UNHCR and the international community with regard to their protection.

The repatriation of Biafran children marked the UNHCR’s first major involvement in the movement of non-European refugees (UNHCRA 11/2/61-610.GEN.NIG.UC.1 [C1]). The 1951 Refugee Convention, which is the centerpiece of international refugee protection and the work of the UNHCR, started out principally as a European treaty, limited to events occurring before 1951 that had caused cross-border displacement in Europe. The adoption of the Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees by the UN General Assembly in 1967 removed these limitations and essentially universalized the international refugee definition and the rights set forth in the Convention (Schoenholtz Reference Schoenholtz2015:83). During the Biafran war, these UNHCR RSD processes had not fully crystallized. Yet, the politics of naming the conflict and classifying its victims are evident in the debates over humanitarian intervention.

UNHCR High Commissioner Sadruddin Aga Khan was initially reluctant to become involved in the major internal conflicts of the 1960s. Despite evidence of massive human suffering, the UNHCR assumed a “policy of strict non-involvement” (Loescher et al. Reference Loescher, Betts and Milner2006:145). Part of the UNHCR’s consideration was that the displacements in Nigeria were largely internal rather than external. As such, the situation was not a matter within the purview of the High Commissioner and not a matter of direct concern to the UNHCR. This was in line with the UN’s overall position on the conflict. UN Secretary-General U Thant took the position that the war in Nigeria was a civil war and, under the UN Charter, therefore outside the jurisdiction of the UN. The Secretary-General was also unwilling to take any initiative that might have offended major powers or African states, most of which viewed the conflict as a domestic affair (Loescher et al. Reference Loescher, Betts and Milner2006:146).

In spite of its general reluctance to become involved in the conflict, the UNHCR played a limited role in humanitarian activities during the war. In 1969, it provided humanitarian assistance to some 40,000 Igbo refugees in Equatorial Guinea and other African countries at the request of Nigerian authorities (UNHCR 2000:47). The UNHCR was not involved in the evacuation of the Biafran children, which was planned and executed by relief agencies operating in Biafra. However, with the end of the war in January 1970, the Nigerian government requested the UNHCR’s assistance in repatriations from several countries, including that of over 4,000 children from Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire. Even though the UNHCR facilitated the repatriation of the children, it considered these responsibilities outside its core mandate functions. The UNHCR officials, including High Commissioner Aga Khan, made it clear that the organization’s role in the repatriation and protection of the children was only part of the High Commissioner’s “good offices” responsibilities (UNHCRA 11/2/61-610.GEN.NIG.UC.1 [C2]). The “good offices” responsibility refers to the UNHCR’s obligation to assist groups outside its mandated functions if the General Assembly or the Secretary-General invites the UNHCR to extend its “good offices” to such groups (UNHCR 2017a). In spite of this official position, however, Aga Khan was personally very supportive of the UNHCR’s role in the repatriation, as evident in his shuttle diplomacy to Nigeria, Gabon, and Côte d’Ivoire to reach agreements on the modalities of the operation. Under Aga Khan’s leadership, the UNHCR facilitated meetings between these governments at a time of fraught diplomatic relations (UNHCRA 11/2/61-610.GEN.NIG.UC.1 [IM1]).

The UNHCR approached the repatriation of the children differently from similar assistance it provided to Biafran refugees in several other African countries including Cameroon, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and Ethiopia (UNHCRA 11/1-1/0/GHA/NIG [RS1; UNHCRA 11/1-1/0/ETH/NIG [RS2]). The term “internally displaced person” had not gained currency at the time of this conflict. In official and public discussions of conflict, the term “refugee” was used broadly for both those internally displaced as well as for those outside their country of origin (Goetz Reference Goetz2001). However, there was clear reluctance on the part of UNHCR officials and the Nigerian government to apply the term “refugee” to the evacuated children. What explains the reluctance to designate the children as refugees? The answer lies in UNHCR policies, wartime diplomatic hostilities, and the politics of naming in international humanitarian interventionism.

Biafra was not recognized by the UN when it declared itself a sovereign state in 1967, and only a few countries accorded it recognition.Footnote 3 Throughout its involvement in the humanitarian crisis therefore, the UNHCR only recognized the Nigerian state, even though UNHCR personnel dealt with the Biafran officials to negotiate access and plan relief activities. This highlighted a key paradox for UNHCR interventions. Scholars of refugee studies have pointed out that the UNHCR refugee status determination process poses protection challenges because it is founded on a basic contradiction. On the one hand, engagement with states and government action is essential for effective refugee protection. On the other hand, however, the UNHCR refugee status determination process is premised on at least partial government failure (Kagan Reference Kagan2005). This paradox was certainly evident in the Nigerian civil war, where UNHCR’s intervention was influenced by the interests of the Nigerian government, whose actions and failures were partly responsible for the plight of the refugees in the first place.

Before its involvement in the repatriation, the UNHCR had come under criticism from humanitarian groups and the media for not doing enough to address the suffering in Biafra. One press report accused the UNHCR’s “cumbersome machinery,” whose role is limited to refugees crossing international boarders, of giving only minimal aid to Biafrans who had fled to neighboring Dahomey, Ivory Coast, Gabon, and Equatorial Guinea (Berlin Reference Berlin1969:10). This criticism extended to the United Nations, which was accused of being blind to the plight of the longsuffering Biafrans. UNHCR officials worried that such critical press on the Nigerian civil war could diminish its reputation as an international humanitarian agency (UNHCRA 11/1-1/0/GAB.NIG [IM3]).

Within the UNHCR, there were no questions that Igbo people who had fled across international borders could be labeled as “refugees” under the terms of the Geneva Refugee Convention. However, there were internal debates over the status of unaccompanied children who had been evacuated from the war zone to countries that recognized Biafra. Were these children also Convention refugees? Even though under the 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Protocol, refugee children were legally indistinguishable from adult refugees, the status of the Biafran children was contentious.Footnote 4 The UNHCR’s legal division outlined its legal position thus:

The United Nations recognizes the state of Nigeria only, not Biafra. To the High Commissioner therefore, the recognition of Biafra by certain African states (such as Gabon) is not binding… It may be said that children of such tender age cannot claim any fear of persecution for themselves. However, as long as we do not know the reasons why the parents sent their children away and why the parents could not come themselves, it is felt that the children be given the benefit of doubt. This would be in agreement with the decision in respect of Jewish children evacuated to Europe from the United Arab Republic after the five-day war.

(UNHCRA 11/1-1/0/GAB.NIG [IM3])In spite of this legal argument, UNHCR officials, aware of the politically sensitive nature of the repatriation exercise, took a pragmatic approach and publicly described the children as “evacuees” or simply “Nigerian children,” rather as refugees or “Biafran children.”

Diplomatic Tensions

The diplomatic tensions arising from the war complicated the UNHCR’s role in repatriating the evacuated Biafran children. The Nigerian government distrusted the humanitarian airlift, which it viewed as a cover for the supply of arms and ammunition to Biafra. Nigerian officials believed that Biafran war propaganda had made many humanitarian agencies politically sympathetic to the Biafran cause (Nwaka Reference Nwaka2015:65–83). They perceived wartime international humanitarian support for Biafra as sabotaging the blockade of Biafra, undermining their war efforts, and unduly prolonging the conflict. Their position, which was unacceptable to some aid agencies, was that relief supplies should be channeled through the Nigerian government to the affected conflict areas, which they still considered part of Nigerian territory. For these reasons, Nigerian official urged the U.S. government to supress the activities of organizations collecting funds to support Biafra (Bigart Reference Bigart1970:22). The Nigerian government also barred certain countries, including France, Portugal, South Africa, and Rhodesia, from providing aid because of their perceived hostility (Gribbin Reference Gribbin1973:52).

The Nigerian government downplayed the extent of the humanitarian crisis. Where aid agencies and Biafran officials talked about the refugee problem, Nigerian officials referred to “displaced people.” The Nigerian leader General Yakubu Gowon pledged that the federal government would provide national leadership in tackling the issue of “displaced persons.” He outlined a five-point program aimed at preserving the unity of the country that included a “nationally coordinated resettlement and rehabilitation program for displaced persons” (Africa Report 1967:39; Elaigwu Reference Elaigwu2009:115). Although the plan involved the resettlement of those who had fled the country because of the war, there was no reference to “refugees.” Other official Nigerian documents published during the war hardly refer to refugees. This reflected Nigeria’s position that the conflict was an internal matter and its opposition to internationalizing the war. Instead, there are references to “displaced persons,” “evacuees,” and even “escapees.”Footnote 5 In contrast, the Biafran leader, Chukwuemeka Ojukwu, frequently described those displaced by the war both within and outside the country as “refugees fleeing atrocities committed against our people” (Ojukwu Reference Ojukwu1968:2).

The Nigerian government opposed all airlifts to Biafra but was particularly opposed to the evacuation of the children to Côte d’Ivoire and Gabon because it saw this as further internationalization of the conflict. Determined to take matters of war relief into its own hands, the government gave full control over coordination of the operations to the Nigerian Red Cross rather than the ICRC (Heerten Reference Heerten2017:295). The government also opposed the role of Côte d’Ivoire and Gabon because of their open support for the Biafran cause. It reacted strongly to what it termed “illegal” flights made by the Catholic Church Charity, Caritas, through São Tomé and Gabon. Nigerian officials considered the evacuated children as having been illegally taken away from Nigeria and described them as temporary Nigerian “evacuees” who should be returned to the country as soon as the conflict was over (Federal Republic of Nigeria 1967b:2–8).

The recognition of Biafra by Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire, which complicated the repatriation efforts, can be linked to post-colonial politics and the decision of the De Gaulle government in France to support Biafra. The French government officially declared support for Biafra in July of 1968. Referring to the airlift operation, French Foreign minister Michel Debré stated that Biafra was “a kind of genocide,” with “thousands of children being evacuated in physical conditions that makes one think of the worst horrors of the last World War” (Griffin Reference Griffin, Moses and Heerten2018:156). France’s support for Biafra has been explained in terms of Paris’ strategic interest in breaking up Nigeria, which through its size was seen by France and its African ex-colonies as overshadowing Francophone presence in West Africa (Heerten & Moses Reference Heerten and Moses2014:176; Gould Reference Gould2012). This, combined with consideration of the potential of an oil-rich independent Biafra grateful to Paris, shaped French foreign policy (British National Archives [Hereafter BNA] FCO 65/347; BNA FCO 65/270). French official humanitarian response was therefore not devoid of politics. Rather, post-colonial regional politics conjoined with efforts to ride the wave of French domestic humanitarian concern.

Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire were the main conduits of French support for Biafra. France delivered arms to Biafra, mostly channelled through Côte d’Ivoire. Projecting its post-colonial power through the ties of Françafrique, the French government put pressure on president Omar Bongo of Gabon to support Biafra. In Libreville (Gabon’s capital), French ambassador Maurice Delaunay convinced a reluctant Bongo to cooperate with the relief operation, despite strong objections from Nigeria. Bongo’s hesitance was likely due to the fear of Nigerian retaliation. However, the memory of the 1964 French intervention in his country as well as the understanding that his position in power was due to French support, led him to acquiesce (BNA FCO 95/617; Griffin Reference Griffin2015:123). Leaders of other francophone African countries such as Houphouet-Boigny of Côte d’Ivoire insisted that recognition of Biafra was a humanitarian gesture founded on Biafra’s right to self-determination rather than a political calculation influenced by France (Britain-Biafra Association 1968:3). At the end of the war, Côte d’Ivoire provided political asylum for the Biafran leader Ojukwu, while President Bongo declared that Gabon would accept exiled Igbos (Howe Reference Howe1970:2).

The question of whether the support for Biafra by Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire was driven primarily by humanitarian and human rights concerns or by political calculations remains a matter of debate. What is more certain, however, is that French, Ivorian, and Gabonese roles in the conflict were decisive in the international humanitarian response. President de Gaulle’s active support of Biafra’s secessionist cause stood in direct opposition to the position of the British government, which wanted to maintain a united Nigeria and thus gave strong support to the federal government of Nigeria. Under pressure from London and facing hostility from the Nigerian government, both Oxfam and the ICRC cut off all aid to Biafra in 1968. Disagreement among international aid agencies on how to respond to the blockade led to the well-known rupture between the future founders of the French charity Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and the ICRC. Encouraged by a French government that supported Biafra’s secession, the French Red Cross started its own relief operation of clandestine airlift of supplies from Gabon to Biafra. Several later founders of MSF were part of the team that broke away from the ICRC. More than a rupture with ICRC principles, the position of the French doctors was partly a response to the specific situation in the field. As direct witnesses to the suffering on the ground, they could not tolerate the ICRC’s hesitation to take a more active and defiant role in the humanitarian crisis (Desgrandchamps Reference Desgrandchamps2014:289).

The deep distrust of France and the Francophone states by the Nigerian government largely shaped its response to the humanitarian crisis. The issue of humanitarian access and assistance for Biafran children inevitably became caught up in wartime diplomatic hostilities and mutual suspicion. This shaped the response of each country to the humanitarian crisis and the way they interpreted the status of those displaced by the war. The Nigerian government was adamant that the evacuated “Nigerian children” were temporary evacuees, not refugees, who were illegally taken out of the country and should be returned to Nigeria. French, Ivorian, and Gabonese officials, on the other hand, considered the “Biafran children” refugees who should be provided long-term care and protection from the war and its aftermath. The fate of these children would become entangled in the politics of post-colonial conflict and international humanitarianism.

The Politics of Repatriation

Even before the war officially ended in January of 1970, following the surrender of Biafra’s leaders, the Nigerian government took steps to repatriate the children evacuees back to Nigeria. The UNHCR would play an important role in this process. The plan to repatriate the children to Nigeria was initially led by the charity organization Americans for Children’s Relief, with the support of the Nigerian government. The plan was unsuccessful, however, because the government could not reach an agreement with the host countries, Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire. This stemmed mainly from the active support which Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire had given to the Biafran cause during the war (Holborn Reference Holborn1975:1392). Furthermore, the Gabonese government took the view that the children evacuated to Gabon were solely its responsibility while they were within its borders and therefore did not welcome any international intervention (Ojeleye Reference Ojeleye2016:87). Gabonese officials protested plans to “abduct” the children from Gabon, claiming that the children had become “pawns who are being sent home to starve to death” (The Star 1970). President Omar Bongo issued a directive to all local voluntary agencies in Gabon to inform them that they should not become involved in the question of Nigerian children who, he claimed, were the responsibility of the Gabonese government (UNHCRA 11/2/61-610.GEN.NIG.UC.3 [IM4]). In addition to the inter-state political difficulties associated with repatriating the children, some humanitarian groups and Biafran sympathizers accused the Nigerian government of a post-war campaign of retribution against the Igbo, suggesting that the children would not receive adequate protection if they were returned to Nigeria.

Another argument against returning the children was that the parents of many of the children had been killed or had disappeared during the war, making it likely that some of the children would not be reunited with their families if returned to Nigeria. A group of French left-wing intellectuals urged the French government to use its influence to prevent the repatriation of the children because their health and safety could not be guaranteed in Nigeria (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1970:29). French doctors attending to the children at a military hospital in Libreville insisted the children must stay in Gabon until security could be guaranteed in Nigeria. Local medical personnel working in the conflict territories also advised against “rushed repatriation” of the children from Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire until adequate arrangements could be made for their resettlement and continued care (Goetz Reference Goetz2001).

In a letter to UNHCR officials in November 1970, the German Caritas Association raised objections to the agency’s role in the repatriations. Theodor Schober, president of the German Christian humanitarian group Diakonisches Werk, stated: “If the repatriation of the children were to proceed regardless of the conditions in Eastern Nigeria… this would amount to an international crime.” Instead of facilitating the repatriation of the children, Schober argued that the UNHCR had an obligation to prevent it (UNHCRA 11/2/61-610.GEN.NIG.UC.1 [IM5]). Other humanitarian groups accused UNCHR officials of complicity in stampeding the process of repatriation, noting that due to the critical situation in former conflict zones, “most of the families were probably not interested in having their children back at this time” (UNHCRA 11/2/61-610.GEN.NIG.UC.1 [IM5]). In a scathing protest letter to M.T. Jamieson, the UNHCR Director of Operations, Claire Glorieux of the Centre for Biafran Children in Libreville warned that repatriation would put the lives of the children at stake and would “mean death for many of the children” (UNHCRA 11/2/61-610.GEN.NIG.UC.1 [C3]).

Responding to these concerns, UNHCR officials clarified that the agency had made every effort to guarantee the safety and security of the children in Nigeria. They clarified that although the repatriation was essentially a “Nigerian operation,” the UNHCR had done the utmost within the scope of its responsibilities to ensure that “transportation, reception and re-integration of the children is performed in the best condition” (UNHCRA 11/2/61-610.GEN.NIG.UC.1 [IM6). They assured skeptical humanitarian groups that UNHCR officials had visited all the resettlement centers in Eastern Nigeria before the repatriation and during the repatriation to ensure that the conditions were adequate for the resettlement of the children (UNHCRA 11/2/61-610.GEN.NIG.UC.1 [IM7]). Indeed, although there were sporadic reports of arbitrary arrests, ill-treatment, and killing of former Biafrans in the immediate aftermath of the war, there was no evidence that this was systemic or orchestrated by the victorious federal government (Amnesty International 1970:11).

On the other side of the conflict, Nigerian officials demanding immediate repatriation claimed that the children were not well cared for in Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire. They accused Gabon of manipulating the humanitarian organizations that arranged the “Biafran babies” operation (West Africa 1970). These claims were not unfounded. While the children were generally well cared for in Gabon, relief workers who visited the camps in Côte d’Ivoire reported local resentment stemming from the belief that the refugee children fared better than the local children. The camp was surrounded by high wire fence which separated the Biafran children from the local people. One American nurse at the camps noted: “The locals resent us bitterly, and they resent the children more” (UNHCRA 11/2/61-610.GEN.NIG.UC.3 [R2]). Officials also observed that many of the children showed evidence of physiological and emotional trauma.

Eager to have the children returned, the Nigerian government sent representatives to the refugee centers in both Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire and assured that it could identify the children and guarantee their safety and wellbeing in Nigeria. Privately however, Nigerian officials conceded that some of the children were unidentifiable. The Nigerian government also claimed that the evacuated children were not all from the former conflict zones. It maintained that many of the evacuated children were from areas outside the former Biafra, challenging the narrative of “Biafran babies.” In all, Nigerian officials sought to reassure the international community that it was prepared to receive the repatriated children which they consistently described as temporary Nigerian evacuees. They stated that the reception centers prepared for the children in Onitsha, Enugu, and Umuahia were adequately staffed by medical and childcare experts provided by the government and partner relief organizations such as the International Union of Child Welfare Nigeria (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1970:29; see Figure 1).

It was in a bid to break the impasse that the Nigerian government asked UNHCR High Commissioner Sadruddin Aga Khan to assist with negotiating the repatriation of the children with the governments of Côte d’Ivoire and Gabon, with which it had severed diplomatic relations. In public statements, UNHCR officials reiterated the position that it “did not consider these children to be refugees and therefore, its offer of assistance in the repatriation fell within its good offices activities” (Goetz Reference Goetz2001:14). The Government of Nigeria accepted this position, affirming its claim that the children faced no fear of persecution in Nigeria. The voluntary decision of a migrant to live in another country, Nigerian officials claimed, could not be grounds for declaring such a person a “refugee.” In a letter to High Commissioner Aga Khan, the government stated that it “is unable to accept that one of the criteria under which the status of refugee is conferred on any person under the appropriate Geneva Convention is a voluntary wish of the person to live outside his country” (Goetz Reference Goetz2001:14). Given prevailing diplomatic tension, the UNHCR did not actively publicize its role in the operation and discouraged its officials from doing so. One internal memorandum urged officials not to give any publicity to the operation in view of its “very delicate nature” (UNHCRA 11/2/61-610.GEN.NIG.UC.1 [IM8]).

UNHCR officials also had to respond to critics who questioned why the agency considered its role in the repatriation of the children merely as part of the High Commissioner’s good offices mandate rather than as part of the agency’s core mandate. UNHCR’s official response to these queries is captured in one memorandum which stated:

…concerning eligibility for assistance, any person who is a bona fide refugee on the grounds of nationality, race, ethnic origins, religion etc. may benefit under our programs… The Nigerian children in the camps are excluded from the project not on account of their nationality but because they cannot be considered refugees under the Convention. The financing of their repatriation is provided from earmarked funds made available following the High Commissioner’s appeal undertaken under his good offices.

(UNHCRA 11/2/61-610.GEN.NIG.UC.1 [C4])Through a flurry of shuttle diplomacy which included meetings with Nigerian and Biafran officials as well as visits to Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire, High Commissioner Aga Khan was able to iron out an agreement between the countries involved to undertake repatriation of the children under the supervision of the ICRC and UNHCR officials (Daily Telegraph 1970:7). Between November 9 and 22, 1970, 891 children were repatriated from Côte d’Ivoire in an operation coordinated by UNHCR officials. This was followed by the airlift of the children in Gabon in two stages: the first groups were airlifted between November and December 1970, and the second between January and February 1971. Although the UNHCR presented the airlift as a “Nigerian operation,” the agency’s officials worked closely behind the scene with humanitarian groups and government officials in Nigeria, Gabon, and Côte d’Ivoire (UNHCRA 11/2/61-610.GEN.NIG.UC.3 [IM9]). In all, 3,711 of the refugee children in Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire were repatriated by an airlift consisting of 78 flights. Most of the cost of flying the children back to Nigeria, estimated at USD500,000, was donated by Denmark as part of its contribution to the relief efforts (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1970:29).

The repatriation of the children was a sensitive subject politically in Nigeria, where the victorious federal government presented it as evidence of its commitment to post-war national reconstruction and reconciliation. Soon after the war ended, the Nigerian head of state, Yakubu Gowon, declared a policy of reconciliation conveyed in the slogans “One Nigeria” and “No Victor, No Vanquished.” The end of the war and the victory of the federal government, Gowan proclaimed, was a victory for all Nigerians (Elaigwu Reference Elaigwu2009:181). The return of the evacuated children from Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire was symbolic of the post-war reconstruction and rehabilitation process. When the first group of 82 children from Côte d’Ivoire was returned to Lagos on November 9, 1970, they were received at the airport by Gowon in a well-orchestrated media event. “It’s not your fault that you left your country,” Gowon told the children as he welcomed them, but “we are very happy to see you back” (Boarders Reference Boarders1970:11).

Receiving the last group of repatriated children a few months later, Gowon paid tribute to the UNHCR and High Commissioner Aga Khan for facilitating the repatriation. Aga Khan, who accompanied the children on the flight from Gabon, thanked Gowon for his “great generosity and magnanimity” during and after the civil war. He called on other countries to emulate Nigeria’s example in bringing an end to animosity and disputes. Recalling that after the Spanish civil war, many Spaniards who had fled their country had not returned home because they had fought on the side that lost, Aga Khan noted that the contrary had been the case in Nigeria. He expressed admiration for the “ease and speed” of the repatriation (United Nations 1971). Within the Nigerian government, the repatriation of the children was considered an important achievement in the national post-conflict reconciliation effort.

Most of the repatriated children were eventually reunited with their families in the former conflict zones. The children were initially accommodated in receiving centers established under the auspices of the Nigerian Red Cross and supported by other international organizations, including the World Food Program and UNICEF. Children too young to remember their parents or where they came from were driven around the countryside, sometimes sixty miles a day, in the hope that they might recognize their surroundings. Humanitarian agencies involved in the reunification exercise reported that it was a “slow and heartbreaking process” (The Star 1970:7).

The repatriation also removed for Nigeria a major obstacle to the resumption of normal diplomatic relations with Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire. At the UN, the plight of the Biafran children became part of broader discussions about the importance of the UNHCR and its refugee aid program in developing countries. The successful repatriation of the children under difficult political circumstances, and the role of High Commissioner Aga Khan in the process, was heralded as an example of the important work of the UNHCR and the aid it provides to “millions of Africans made homeless by tribal conflicts and political unrests” (Teltsch Reference Teltsch1970:25). One news report titled “Charming Prince,” extoled the quiet intervention of “Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan, uncle of the young Aga and High Commissioner for Refugees” in getting the agreement of all the parties involved that made the repatriation possible (The Guardian 1970). In appreciation of the UNHCR’s role in the repatriation, the Nigerian government made a commitment to increase its contributions to the agency. UNHCR officials considered this an important vindication of the organization’s role in the operation. To them, this was evidence that its role in the operation had “paid good dividends” (UNHCRA 11/2/61-610.GEN.NIG.UC. 3 [IM10]).

Conclusion

As late as 2011, the UNHCR reported that some Biafran emigrants still remained at risk of statelessness in Côte d’Ivoire (UNHCR 2011). The more recent controversy over whether President Ondimba is one of the Biafran children left behind in Gabon is an indication of the endurance of this episode in the collective memory of those affected by the conflict. The evacuation and repatriation of Biafran children during the Nigerian civil war offer insight into the international politics of naming in humanitarian interventionism. It shows how sematic and political differences over the labeling of the conflict and its victims extended to unaccompanied displaced children—the most vulnerable victims of the conflict. While the opposing positions of the Nigerian government and Biafran authorities on the status of the children may be seen as a predictable extension of the politics of war, the disagreement extended to the role of other states, the UNHCR, and various relief agencies.

Evidently, the interest of the children as victims of conflict was not always the primary consideration in the politics of classifying these forced migrants. The decision of Gabon and Côte d’Ivoire to accept the evacuated children was informed by their support for Biafra, which in turn was influenced, at least partly, by their post-colonial affinities with France. Nigeria’s opposition to the airlift of humanitarian relief to Biafra and to the evacuation of the children was influenced by the overriding goal of defeating secessionist Biafra, rather than by consideration for the best interest of the children. The UNHCR’s role in the repatriation of the children was also shaped by diplomatic and political calculations. Despite concerns expressed about the return of the evacuated children to Nigeria immediately after the war, the UNHCR acceded to the request from the Nigerian government to facilitate the return of the children. Beyond the politics of naming, this episode demonstrates how state interests and international politics shape post-colonial humanitarian interventionism.

The lessons from this episode bear contemporary relevance. With growing global political anxieties about irregular migration and the refugee “problem,” it is important to pay close attention to the politics of labeling. Beyond the technicalities of official Refugee Status Determination processes, the international legal and policy framework for protecting forced migrants fleeing war and persecution continues to be defined by the politics of naming. The case of the evacuation and repatriation of Biafran children reminds us that the discourse of classifying those fleeing war and persecution is deeply political, often shaped more by the vested interests of states and the politics of humanitarian interventionism than by the best interests of those displaced.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the Social Sciences and Human Research Council of Canada for a research grant that supported my research at the Nigerian National Archives, Ibadan, and at the UNHCR Archives, Geneva, Switzerland. I am also grateful to Francis Ibhawoh and Patrick Ibhawoh whose vivid memories and personal stories of the Nigeria-Biafra war ignited my interest in this topic.