Introduction

Pastoral conflicts in Ethiopia are multifaceted and complex. Such conflicts occur between pastoralists of different ethnic groups as well as between pastoral and agro-pastoral groups of differing ethnicities. Victims and participants vary from one locality to the next. The conflicts affect social and economic activities by undermining local relationships. They also disrupt investment activities, thereby reducing the pace of economic development in pastoral areas of the country. The presence of territorial claims and counterclaims, manifested along ethnic lines, has increased the complexity of pastoral conflict (Alemmaya & Hagmann Reference Alemmaya and Hagmann2008). Meanwhile, pastoralists have resisted the expansion of the state administrative structure into pastoralist-inhabited areas (Alemmaya & Hagmann Reference Alemmaya and Hagmann2008); the main reasons for such resistance are “pastoral land alienation” for investment purposes and the establishment of national parks, which put pressure on pastoral grazing areas and limit economic opportunities (Mousseau & Martin-Prével Reference Mousseau and Martin-Prével2016).

The politicization of land in connection with the country’s transition toward ethnic-based federalism has contributed to the deterioration of interregional relations. This has been exacerbated by the federal state, which has played an ambiguous role in reconfiguring the conflicts to achieve its own political goals (Lober & Worm Reference Lober and Worm2015). Recurring clashes between neighboring pastoral-dominated regions on the administrative boundary have undermined the pre-existing resource-sharing arrangements. In Eastern Ethiopia, this has resulted in the unproductive use of pasture for livestock grazing and a subsequent diminished return from livestock production. Cross-border movement in search of pasture and water involves trafficking of firearms, increasing the space for violent conflict among pastoralists and resulting in regional instability (Galaty Reference Galaty2016). An increase in the use of lethal weapons, such as automatic machine guns, has increased the human costs of these conflicts (Unruh Reference Unruh2006).

There are a number of studies which investigate the causes of conflict in pastoral areas. Some tend to attribute the conflict to the transition of the Ethiopian political system toward ethnic-based federalism and competition for territorial control.Footnote 1 For example, Fekadu Adugna (Reference Fekadu.2012) studied the conflict between the Borana and Gari clans, while Debelo Regassa (Reference Regassa2012) investigated the conflict between the Guji and Burji clans in southern Ethiopia. There have been a number of developments in the nature and complexity of the conflicts in 2016 and 2017. Some studies have associated the pastoral conflict in eastern Ethiopia with resource scarcity, as exacerbated by climate change (Beyene Kenee Reference Beyene Kenee2013). Still other scholars link the cause to commercialized livestock raiding, in which stolen animals are illegally sold to large-scale live animal exporters (Gray et al. Reference Gray, Sundal, Wiebusch, Little, Leslie and Pike2003; Alemmaya & Hagmann Reference Alemmaya and Hagmann2008). However, each study has looked at a single cause of violent conflict, overlooking the dynamism and multidimensional nature of the causes of the conflict and the interaction of the causes. None of these studies has examined the violent conflict between the Jarso and Gihri groups, as well as between the Ittu and Issa clans, where the context of the violent conflict differs substantially on various socioeconomic grounds. To fill this gap, this article makes use of four theories (resource scarcity, property rights, political economy, and political ecology), which enable an understanding of the multiple perspectives that have bearing on the causes of conflict in Chinaksen and Mieso Districts in eastern Ethiopia. As a conceptual lens, no single theory can fully capture the complexity of the conflict. But this approach has been found to be relevant in producing a fresh look at explaining and understanding conflict and in shedding light on ways in which the state (political) institutions might be able to build sustainable peace.

Resource-based violent conflict between Somali and Oromo pastoral groups has been increasing in scale and frequency at the boundary of the Oromia and Somali Regional States since December 2016. The economic and social costs of the violent conflict have become increasingly significant. The need for a response at the state level to this precarious situation has informed this study. This article examines the causes and dynamics of the violent conflict and explores institutional arrangements in peacebuilding, based on evidence from selected key informant interviews and focus group discussions with pastoral and non-pastoral groups. This analytical approach combines narratives, mapping, and timeline analysis to explain processes and to map actors based on the roles they have played in the conflict. The second section provides a literature review on causal analysis and peacebuilding. The third section describes the data collection methods and analytical approach. Section four presents the findings of the research, and the final section concludes the piece.

Theories Explaining Conflict and Peacebuilding

Four streams of thought are crucial in explaining resource-based conflict. The first is the property rights school. This perspective considers poorly defined and enforced property rights as a major source of resource conflict (Alston et al. Reference Alston, Libecap, Mueller, Drobak and John1997; Demsetz Reference Demsetz1967). The scholars who follow this reasoning argue that resource scarcity cannot lead to conflict. Rather, it causes a change in property rights favoring privatization. The purpose of change is to increase benefits from the resource through investing in it and thereby increasing its productivity. This is achievable through technological change (Demsetz Reference Demsetz1967). An alternative approach could be to hold the property in common to overcome disputes arising from possible incursion upon privately used land. In both cases, the failure to undertake a desirable institutional change is an important cause of resource-related conflict. Thus, peacebuilding efforts need to consider institutional change as an imperative.

The second theoretical explanation for the cause of conflict arises from the environmental security group. This school of thought associates the source of resource conflict with resource scarcity (Homer-Dixon Reference Homer-Dixon2001; Hauge & Ellingsen Reference Hauge and Ellingsen1998; Homer-Dixon et al. Reference Homer-Dixon, Boutwell and Rathjens1993). The environmental security group classifies the sources of scarcity as belonging to one of three dimensions. These are supply-induced (resource is degraded faster than it is renewed), demand-induced (increment in population or per capita consumption), and structural scarcity (inequitable distribution of resources or more concentration under the control of a few while the rest of a society falls short of the resource) (Hauge & Ellingsen Reference Hauge and Ellingsen1998).

The third explanation is the political economy argument. This theory uses greed and grievance as conceptual perspectives to explain the causes of conflict. Greed refers to engaging in violent conflict which is motivated by the need to accumulate wealth through taking away others’ resources. Grievance occurs when a certain group is systematically marginalized from taking part in important political decisions. Such political and economic marginalization prevails in the policies and systems of governance. Grievance advances due to elite capture, economic instability, and rent-seeking behavior by certain groups. This characterization of the causes of conflict as greed- or grievance-based has often been labeled as flawed in many accounts related to diversity along ethnic and religious grounds. Nevertheless, where grievance remains a cause, the necessary measures to alleviate the situation would involve policy interventions to address the causes of grievance, such as inequality and the need for increased political rights (Collier Reference Collier2006).

The fourth theory is the political ecology argument. Developments within political ecology theory can be divided into three generations (Bohle & Fünfgeld Reference Bohle and Fünfgeld2007). The first was in the 1980s, when it addressed the socioeconomic and political dimensions of environmental problems, with an emphasis on the poor and marginalized groups within their historical, economic, and political contexts. The second was in the 1990s; it focused on the politics, power relations, resource access and control, and definition of property rights to resources, involving negotiation within the political space. The third was in the 2000s, where it emphasized the link between environment, geopolitics, and violence, covering aspects of environmental security (Dalby Reference Dalby2002; Collier Reference Collier, Berdal and Malone2000). This link has been criticized since the nature of state governance determines the nature of relationships between scarcity and violence (Peluso & Watts Reference Peluso, Watts, Peluso and Watts2001).

Until the 2000s, the political ecology theory was silent on the relationship between resource scarcity and violence (Peet & Watts Reference Peet, Watts, Peet and Watts2004). The political ecology theory subsumes elements of the other two theories, including how ill-defined property rights and environmental scarcity contribute to violent conflict (Bohle & Funfgeld Reference Bohle and Fünfgeld2007). And the “politics of scale” has been added to the theory to capture the role of scale in defining and explaining environmental problems (Neumann Reference Neumann2009). Robbins (Reference Robbins2019) identifies five dominant narratives of the political ecology theory, one of which is environmental conflict, which is used to explain access to natural resources and conflicts over exclusion from such resources along the lines of gender, class, and race.

A number of empirical studies have employed this theory to analyze conflict and the decision to take action as a response to being marginalized. For example, T. J. Bassett (Reference Bassett1988) indicates how herder-farmer conflicts in Ivory Coast may be explained by land use change. The absence of compensation for crop damage by herders has contributed to sustained conflict. Matthew Turner (Reference Turner1999) identifies the underlying cause of resource-based conflicts as the failure of local institutions to govern resources in Mali and Niger. In a similar fashion, Tor Benjaminsen and Boubacar Ba (Reference Benjaminsen and Ba2019) have underlined how grievances by the pastoralists over the role of a corrupt state in triggering land use conflicts has eventually forced them to join the Jihadist movement in Mali.

It is important to consider the interdependence of these four theoretical orientations in explaining conflict. For instance, political ecology has an influence on the structure of property rights (how they are defined and enforced) and structurally induced scarcity. The four theories are interlinked, with each one compensating for the weaknesses of the others. For these reasons, this analysis relies on all of these theories to explain the causes of conflict and to explore possible institutional responses toward peacebuilding. However, where and when the failure of political institutions contributes to the emergence of violent conflict, political economy and ecology theories are more powerful in explaining the conflict. Therefore, this article relies most heavily on these theories to explain the border conflict.

As this article explores institutional options regarding peacebuilding, it is important to provide a brief discussion of the theory of peacebuilding. Peacebuilding is understood as a comprehensive concept that encompasses, generates, and sustains the full array of processes, approaches, and stages needed to transform conflict toward more sustainable and peaceful relationships (Lederach Reference Lederach1998). The various approaches to peacebuilding can be classified as liberal, local, and hybrid. The liberal approach to peacebuilding involves the promotion of democracy, market-based economic reforms, and the involvement of other institutions associated with modern states as a driving force for building peace (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Paris and Richmond2009). Local peacebuilding is based on cultural norms using traditional systems of peacebuilding. A hybrid peacebuilding approach considers the interaction of local peacebuilding processes (by relying on customary practices) with liberal peace agents (Ginty Reference Ginty2010). This approach connects the liberal and local peacebuilding methods. The critiques of liberal peacebuilding and the need to adopt a more accommodative and emancipative approach have shifted the discourse of peacebuilding toward hybridizing the liberal with the local (Anam Reference Anam2015). The liberal peacebuilding approach is often criticized for disconnecting peacebuilding processes from the local contexts (cultural values and norms). It is often assumed to be artificial, since the peace resulting from this process becomes dependent on national and international actors rather than on the local community. Hybrid peacebuilding does not ignore liberal peace agents, their networks and structures; instead, it considers: “(1) the ability of local actors to resist, ignore or adapt liberal peace interventions; and (2) the ability of local actors, networks and structures to present and maintain alternative forms of peace making” (Ginty Reference Ginty2010:392).

Nevertheless, the hybrid peacebuilding approach is not without its own weaknesses. It tends to romanticize the local/traditional approach, which may contradict universal human rights and liberal democracy. For instance, the type of punishment issued to perpetrators of violence may involve torture, which violates universal democratic rights (Boege Reference Boege2011; Richmond Reference Richmond2011). Peacebuilding in the pastoral context can be implemented in three ways: through state intervention, through the use of customary systems, or by combining the state and customary approaches. The third category falls under the designation of hybrid peacebuilding (Anam Reference Anam2015). This is often seen where state authorities empower customary systems to complement and compensate for the weaknesses of the state system (Beyene Kenee Reference Beyene Kenee2017). This article draws on the specific aspects of these theoretical concepts and relies on insights from the field to identify institutional options regarding peacebuilding.

Methodology

The study area

This study was conducted in eastern Ethiopia in two administrative districts: Mieso and Chinaksen. There have been conflicts between the Oromo and Somali pastoral groups in these districts. The conflict in Mieso is between the Somali clan of Issa and the Oromo clan of Ittuu, while in Chinaksen the conflict is between the Jarso clan of Oromo and the Girhi clan of Somali. The border dispute and resulting violent conflict have existed for a long time along the long border between the two regional states. However, the scale of violence and human cost is extremely high in Mieso and Chinaksen (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Location of the study area

The involvement of both state and non-state actors in the resolution of this violent conflict makes it unique. These sites were selected based on the history and frequency of pastoral conflicts over the last two decades and a recent border dispute between the two regional states.Footnote 2 The frequency of violence has recently increased, resulting in loss of property and lives. There is no sustainable peace, and pastoralists live in fear. The absence of sustainable peace due to heavy reliance on armed forces to settle the conflicts (while ignoring customary systems) in these areas has had a negative effect on the national economy, since pastoralists live along the major trade route connecting Ethiopia with Djibouti.

Data Collection and Analysis

This article relies on qualitative data from key informants from the Somali and Oromo ethnic groups, experts, district administrators, lawyers, women, youth, and police officers. Extracts from newspaper accounts provided by the state and opposition groups having a stake in the violent conflict were important on a case-by-case basis as the conflict continued. The fieldwork was conducted between June 2017 and November 2017, at a time when the border conflict was severe. Overall, data were collected from twenty-five key informants and twelve focus-group discussions (ten pastoral and two non-pastoral groups), using a pre-defined and open-ended set of questions. The focus group discussion was composed of participants with different backgrounds and domains of knowledge about conflict and the peace process. In addition, conflict–mapping was used to identify actors and their roles and relationships in conflict and peacebuilding. This helped to stimulate an in-depth investigation of cases and issues related to a specific conflict setting and in drawing the pattern of violent conflicts through time. The issues of sites and scales of conflict are argued to be important in the process of mapping conflict (Bjorkdahl & Buckley Reference Bjorkdahl and Buckley2016).

To analyze the data, I used a mixture of methods: narratives, mapping, and timeline analysis. Conflict timeline analysis was used to help understand the interaction between events and outcomes, and how the conflicting parties interpret an event. Information from interviews and discussions was used to draw a timeline considering the major events since the regime change which took place in Ethiopia in May 1991. In this study, agents of conflict, their connections and coalitions, their goals and the incompatibility of these goals, and predispositions influencing the emotions of conflicting parities were examined using mapping, timeline analysis, and narratives. All of these were necessary in order to explore institutions that might help manage the conflicts and build peace.

Identifying institutional options for peacebuilding requires the use of analytical tools considering time factors. For this purpose, a case-study approach to data analysis involved the documentation of evidence on conflict events within the two specific pastoral systems. This produced a chance for a deeper investigation to identify patterns of change in the state-pastoral relations as well as in inter-pastoral conflicts at each site. This was pertinent, as the causes of conflicts and peacebuilding interventions vary across space and time. With this in mind, I used the case-study approach to analyze deep historical grievances and the underlying reasons for the violent conflict.

Findings of the Study

The findings of the study are presented in two separate sub-sections. The first sub-section explains the causes of the conflict by emphasizing territorial claims, referendum, and the link between politicization of ethnicity and administrative boundary. It provides a timeline analysis of events and analyzes how the feuding parties interpreted these events. The relationship of different actors with respect to the conflict is also mapped to explain their roles in the conflict. The second sub-section presents the formal approaches toward peacebuilding, which were identified based on insights from interviews and discussions.

Explaining the Causes of the Conflict

Territorial claims, conflict, and referendum

Prior to 1991, Ethiopia’s government followed the socialist system; it was divided into fourteen provinces without considering ethnic differences. Diversity based on culture, language, and interests was ignored. The political struggle within the country, driven by the need to recognize diversity, contributed to the emergence of a new political system in 1991. An attempt to delineate regional boundaries based on ethnicity in the new political order of Ethiopia has created uncertainty, hostility, and tension between certain ethnic groups, specifically the Jarso and Girhi, as well as the Issa and Ittuu groups.

The main cause of uncertainty and confusion is related to boundaries, which have created contestation between newly created regional states and the ethnic groups that were involved. This process resulted in a referendum which triggered contestation over territoriality between the Somali Regional State and the Oromia Regional State. Such a political transition, from a unitary system of governance to ethnic-based federalism in 1991 following the collapse of the socialist government, has escalated the desire for territorial control and grievance over territorial units lost by both parties due to a second referendum in 2004. Following the referendum, the conflict between Jarso and Girhi persisted. This has been especially true in areas where the regional states have members of their respective ethnic groups included within the territorial units controlled by another regional state. With respect to the entire regional boundary shared between Somali Regional State and Oromia Regional State, the referendum of 2004 covered 85 contested districts and administrative units.

The conflict events and outcomes in the cases of Mieso and Chinaksen can be explained using a timeline analysis. Conflict between pastoralists of the two ethnic groups was exacerbated by boundary disputes between the two regional states following the aggression by the Liyu police in the Somali Regional State in December 2016. Insights from the discussions show that behavioral inconsistency in negotiations and in implementing agreements was an obstacle to the creation of institutions for peacebuilding. On September 12, 2017, the Oromia police fought the Liyu police as an act of revenge, and also to protect civilians in their jurisdiction. The justification for this violence was that the federal forces did not restrain an incursion by the Somali armed forces. This occurrence contributed to greater instability, even as the federal government continued assure the citizens that they would bring the perpetrators of violence to justice. The killing of the former office holder from the Oromo ethnic group who was serving as deputy security head of the Gursum district (neighboring Chinaksen district) created considerable anger. The expulsion of more than one million Oromo residents from the Somali region under the direct order of the Somali region president in September 2017 fueled the violence, which resulted in unprecedented humanitarian crises in eastern Ethiopia.

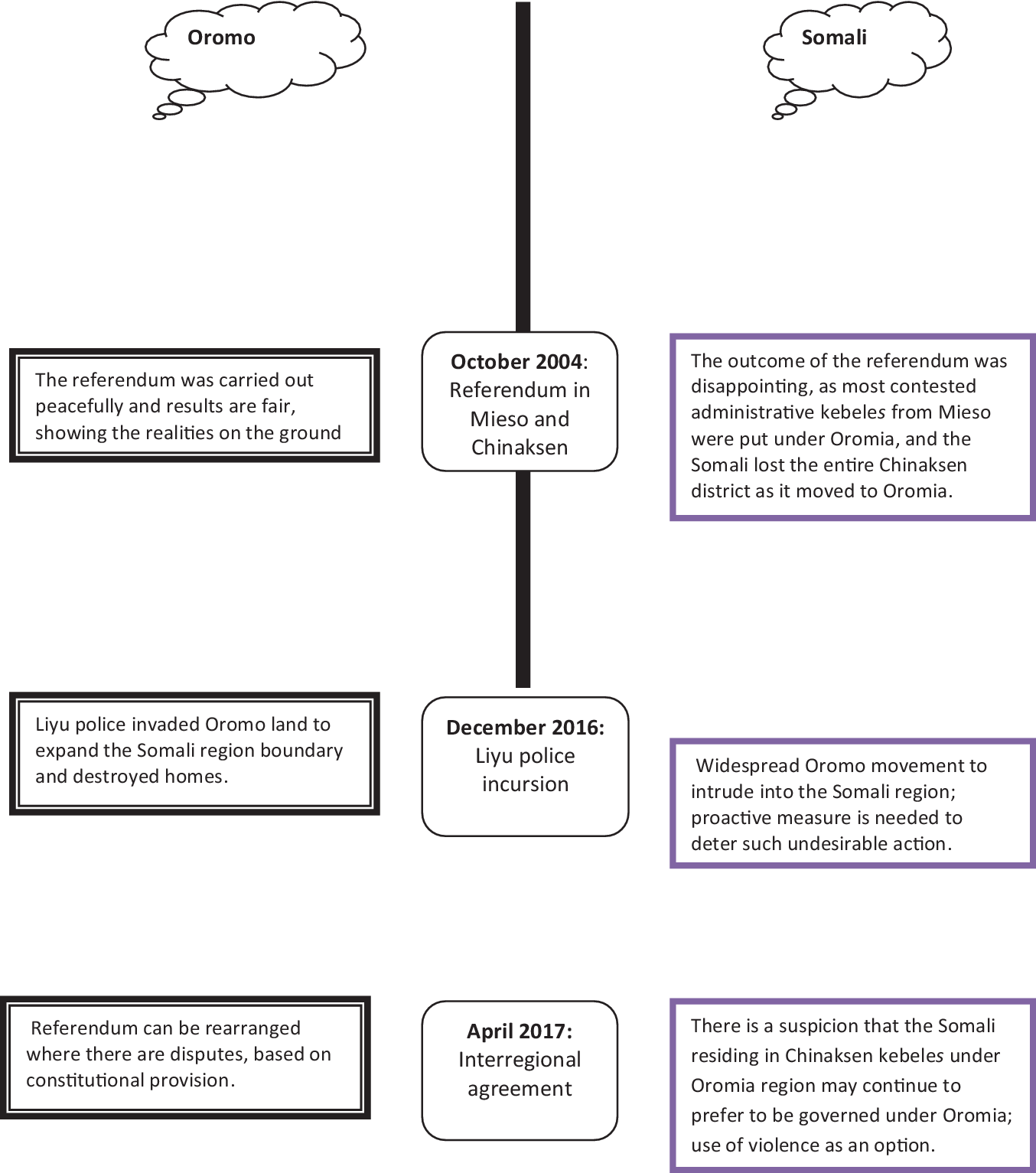

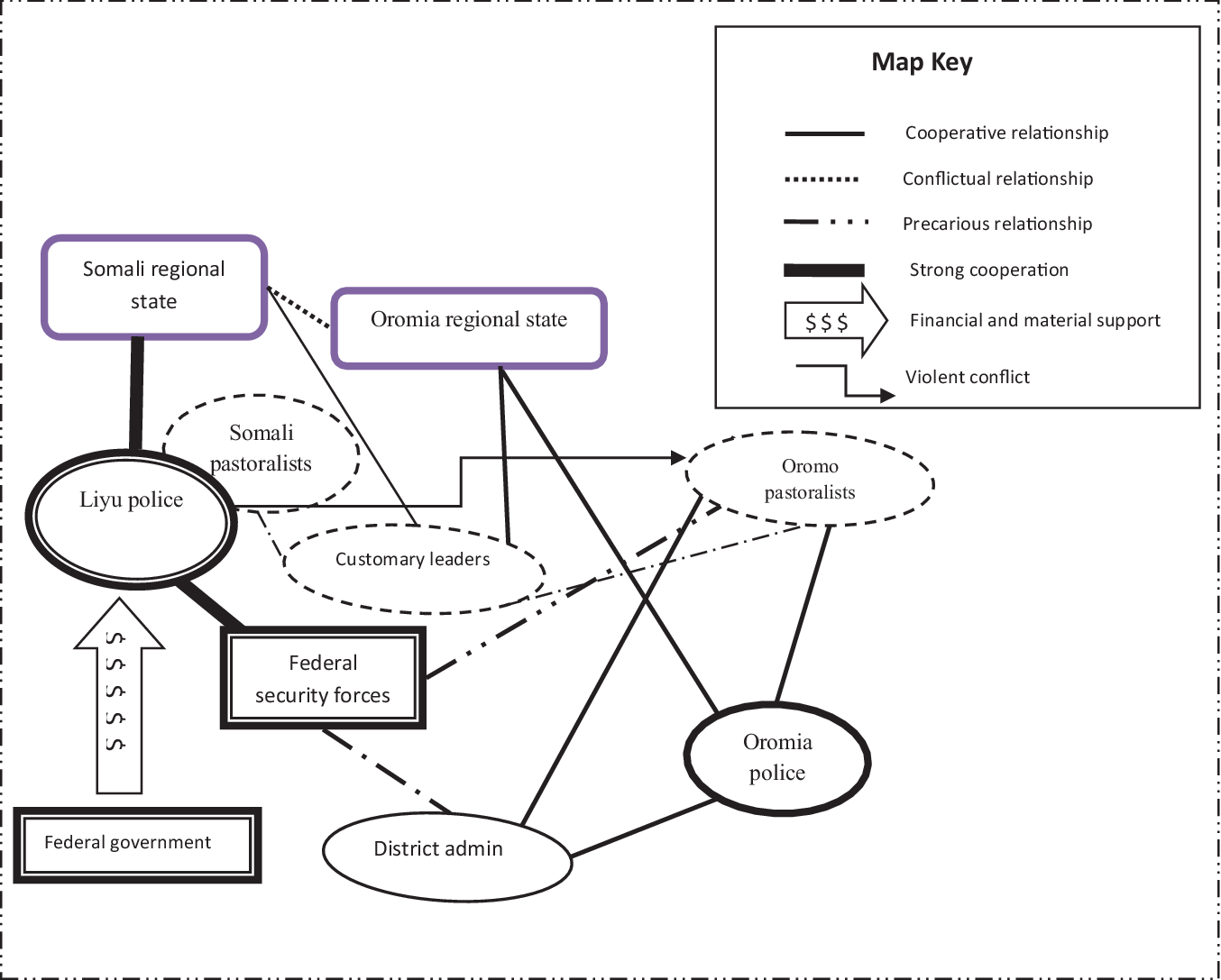

There are three important factors contributing to the current conflict: the implementation of the referendum, the Liyu police incursion, and inter-regional agreements. The Somali and Oromo ethnic groups (see Figure 2) interpreted these events differently. The different reactions of the feuding parties to each event demonstrate the disparity in perception of the outcome that was attributed to each event. For instance, the October 2004 referendum was perceived as realistic and fair among the Oromo pastoralists, while the Somali considered it disappointing, as they lost the entire district. Figure 3 maps the relationship between the feuding parties.

Figure 2. Timeline analysis showing divergence of perceptions

Figure 3. Relationship mapping for the violent conflict between Somali and Oromo pastoralists

Politicization of ethnicity and administrative boundaries

Historical accounts show that the relationship between the Somali and Oromo groups has a complex background. Both groups were key players in the sixteenth-century mass population movements in the Horn of Africa. In addition, the Oromo played a key role in Ethiopian politics beginning in the twentieth century (Clapham Reference Clapham1988). The two regional states share an administrative boundary of more than one thousand kilometers. The earliest recorded interactions between the Somali and Oromo ethnic groups date from the 1500s and 1600s, when the Oromo were expanding to the north, northeast, and northwest (Baxter Reference Baxter1978). The groups competed for more than four hundred years along their borderlands for water, grazing, and agricultural land (Lewis Reference Lewis1966). Ethiopia’s political transition toward a federal restructuring that connects ethnicity, territory, and administrative boundaries triggered the current competition for land. The longstanding interaction between Somali and Oromo is also manifested through marital and cultural relations, which make it difficult to draw borders in a strict sense. As a result, the approach of the ethnicization of territory has been challenged, as it generated inter-ethnic tensions in the process of assigning territorial control (Asnake Reference Asnake2013).

In the past, violent conflict has occurred due to competition for access to grazing land and water points. The pastoralists attempted to prevent intruders from forcefully entering their grazing areas (at times of extreme scarcity) without prior negotiation with the group which held primary use rights to a particular grazing area. The current practice, in association with the current boundary disputes and new territorial claims, emphasizes the redrawing of the boundary on the part of the Somali region. The justification offered for this is that the regional government was not strong enough to properly address the interests of its own people during the 2004 referendum, and hence, some border adjustments were needed. Such a claim was interpreted on the part of the Oromia region as a strategic move to expand the Somali territory. For example, the whole Chinaksen district was administered by the Somali region before the referendum in 2004. Chinaksen town was administered as 07 kebele (the lowest administrative unit) under Jigjiga, the regional capital. However, in 2004 when the referendum was conducted on disputed districts between the two states, Chinaksen was legally moved into Oromia.

Pastoralists explain that the Somali region flew its flags and declared that a particular kebele belonged to it. The Somali group then started evicting villagers by force and looting their property. The region provided wheat grain, as part of food aid, for those who were not actually in need of it but were politically affiliated. The purpose was to manipulate them to change their opinion in favor of Somali regional political elites. Others who did not accept the aid resented those who received it. Competition between the two groups resulted in violent conflict as the affiliated groups provided information for the armed Somali police, triggering violent reprisals. Consequently, the conflict that occurred over the use of grazing resources took on a new shape. The Jarso and Gihri clans, which have historically shared grazing and water resources and lived in the same distinct, were drawn into the hostility and tension. Respondents emphasized that there was a strategic shift toward the creation of interest groups to achieve long-term goals of territorial control.

A comparison of the views expressed by various categories of respondents shows that the strongest interest in raising territorial claims comes from the Somali regional state and not from the Somali Girhi, who are living in harmony with the Jarso Oromo. Public disapproval of the new territorial claim is linked to a lack of good governance. This is explained by the lack of transparency, elite capture, and non-responsiveness that both groups experienced before the 2004 referendum, when they were both administered under the Somali region. During the fieldwork for this study, both ethnic groups claimed that “there is relatively better governance under Oromia region in providing public services (water, health, and schooling).” There is also a “well-organized emergency response at the time of environmental stress (such as food aid and livestock feed).” The pastoralist respondents indicated that they benefited more from the provision of services (water supply, health, and schools). One of the respondents stated, “we have three tap-water supply points developed since 2004 and before that we did not see any water supply service from the Somali region.”

In this case, the Somali region has politicized ethnicity as a strategy for expanding its territory, partly by adhering to the Ethiopian principle of ethnic-based federalism. Responses from the different informants underline the Somali region’s choice for aggression using a special police force (known locally as “Liyu police”), which intimidated and raided the Oromo pastoralists, confiscating their property and killing dozens of them. The locals and the federal government interpret such an action differently. While local people and the district administration emphasized that the aggression was carried out because the Somali region failed to settle the dispute peacefully, the federal government denounced certain interest groups who, they claimed, wanted to destabilize the regional borders and thereby perpetrated the violent actions.

There were cases of intimidation, confiscation of property (mobile phones and laptops) and tearing up identity cards of Oromia Regional State employees by the Somali Liyu police. At the local level, the Somali region prepared a stamp and gave it to the Girhi group, simply to prove to the federal state agents that each contested kebele had sufficient population to justify being governed under the Somali. The Somali Region used “fake population data” to secure a favorable decision by the federal agents. This evidence demonstrates how politicizing ethnicity can cause internal social instability; the pastoral people were forced to support ethnic division and undermine their social cohesion. Furthermore, the rent seeking behavior of the political elites involving all kinds of tactics to gain political support had a counterintuitive effect at the local level by disrupting peace and stability. Therefore, ethnicity in itself has not been the sole cause of the conflict (Schlee Reference Schlee2008). The different cases of manipulation and the use of armed forces to influence the position of different clans in relation to the violent conflict by the political elites can be clearly associated with the political ecology argument (Collier Reference Collier2006).

In Ethiopia, the regime change in 1991 introduced ethnic-based political representation. The intention was to provide solutions to those problems where competing interests tied to ethnic and linguistic groups could be accommodated. However, the creation of regional administrative boundaries based on ethnic identity has brought an unprecedented challenge with respect to building peace (and ensuring stability) in pastoral areas of the country. Different groups are deliberately politicizing ethnicity and boundaries in order to attain their own political ends. There are direct relationships between inter-ethnic conflict and government administrative policies, where such conflict has undermined customary arrangements involving access to grazing resources (Boku & Gufu Reference Boku and Oba2004; Dereje Reference Dereje2013). The Somali Regional State and the Oromia Regional State share a boundary that mainly crosses pastoral-inhabited areas from the northeast to the southeast. The violent conflict has been protracted in the post-2004 referendum along the border of the two regional states. Specifically, the violence perpetrated against the Jarso clan in Chinaksen and the Ittuu of Mieso by an armed group has further escalated the conflict since December 2016. One of the respondents in the focus group discussions at Sodoma-Goro-Misira kebele in Mieso district stated, “We do not know why government fails to protect us and our rights to live on our land.” The violence continued for several months, even after the prime minister had guaranteed a thorough investigation and prosecution of the perpetrators. The political ecology concept best explains such machinations by political elites to achieve their own private interests. The elites use distorted narratives and politicization of ethnicity to profit from the violence.

Mapping the Relationship of Actors in the Conflict

Mapping is used here as an analytical tool to investigate the relationship between actors in the violent conflict, emphasizing their roles. The central point is that the two regional states had incompatible goals. This appears to be the case as the Oromo pastoralists insisted on respect for the 2004 referendum on administrative boundaries, while the Somalis were motivated by their regional state’s desire to expand their territory. The key actors in the conflict were the Oromo pastoralists and the Somali Liyu police. As time passed, the Oromia police occasionally participated in the conflict to protect their people, while the key informants did not appreciate such an action, which the victims of violence perceived as ineffective. The federal forces also discouraged the Oromia police from engaging in violence against the Somali armed forces, because the role of the federal security forces was to prevent the violence from intensifying. The key informants lost confidence in the government, as they perceived that federal forces held an ambivalent position (see Figure 3).

The efforts of the political leaders in settling the boundary dispute did not generate concrete results. There have been several negotiations carried out since December 2016, but they were not successful. As a result, trust has deteriorated, leading to the creation of a “we-they” cleavage within the two societies, despite the fact they have historically co-existed peacefully. One indicator of the loss of trust is evidenced by a statement made by one of the respondents, who said, “The current claim to administer one or two kebeles is not an end in itself, and the Somali Regional State intends to gradually expand its territory by evicting the Oromo pastoralists.” Insights from the interviews also show that the customary leaders tended to take sides and could not freely exercise traditional means to manage the conflicts. The customary leaders were often driven by their own private interests, at the expense of the interests of their community, which cost them community-level respect.

The key actors with different roles and positions in the violent conflict were the Somali Liyu police, the regional states, pastoralists, Oromia police, customary leaders, federal security forces, and the administration of the two districts. In identifying and characterizing the key actors, three important criteria were used: (1) the role of each actor in triggering violence (providing information, mobilizing resources, actions) and building peace (initiating dialogue, creating platforms, monitoring the peace process, enforcing agreements); (2) the way the actors were positioned in terms of existing links and alliances as well as in facilitating peacebuilding, and 3) the way their roles have been affected by changes in the nature of governance (boundary/territorial dispute). These criteria were helpful in concretizing the views of the various respondents.

To map the relationship, historical accounts have shown that resource-based violence has existed between Somali and Oromo pastoral groups. In their first incursion in December 2016, the Liyu police used some Somali pastoralists to obtain information in order to strategize when to attack. Oromia police received support from the Oromia Regional State to protect the security of the Oromo pastoralists, but they also occasionally fought against the Liyu police to protect the civilians. The district administrations deployed kebele militias to monitor village-level security and to undertake preventive measures against violent attacks from the either the Somali pastoralists or the Liyu police. The district administrations were also suspicious of the federal security forces, as they often failed to deter the violent action by the Liyu police. However, the federal security forces also had the additional task of securing the Somali region against the Ogaden National Liberation Front insurgents, and for this reason they cooperated with the Liyu police. The federal government invested in capacity-building long before the boundary dispute started in December 2016 (Figure 3). Hence, the Liyu police implicitly served the purpose of ensuring national security and were as such better armed. Tobias Hagmann (Reference Hagmann2014:49) characterized them as “The special police [who] operate without accountability, effectively a paramilitary force beyond the reach of the law.” The key informants indicated that the Liyu police had been manipulated by the military generals who were affiliated with high-ranking TPLF (Tigray Peoples’ Liberation Front) political elites, whose interest was to weaken the Oromo youth struggle toward a democratic transition in the country. This was the elites’ hidden motive for not protecting innocent civilians from aggression by the Liyu police.

Customary leaders from both the Oromo and Somali pastoralist communities are accustomed to resolving conflict over grazing and water resources. As such, they were involved in addressing the violent conflict. Meetings were convened by both regional states to resolve the conflicts, but their efforts did not generate any better outcome toward building peace. Traditional leaders are unfortunately often influenced by the interests of government agents. The evidence from the field shows that customary leaders were also influenced more by their private interests than by a desire to build sustainable peace. One of the respondents stated, “Some of the customary leaders attending meetings… count on the daily subsistence allowance; they are not concerned about our children suffering from the trauma of violence.” Therefore, customary leaders were perceived, among the pastoralists of both groups, as having a “precarious role.” One of the focus-group participants in Mieso emphasized that “we need [a] little time to resolve resource-based conflicts but this time we are excluded from the process.” The respective regional governments claimed to believe in the positive role that customary leaders play in peacebuilding, but in this case, the leaders were co-opted by the state and so lost public trust.

The mapping in Figure 3 shows the overlapping role of the Liyu police and the Somali pastoralists. At the beginning, the local people and politicians interpreted the violent events between the two pastoral groups differently. For instance, the Ethiopian government considered the violent conflict as an issue between armed Somali and Oromo pastoralists, whereas the local people indicated that it was manufactured aggression, in which Liyu police played a key role in triggering the violence. A deeper analysis shows elements of both interpretations are likely true, but with variability in the intensity of conflict, timing, scale of violence, and outcomes related to the conflicts. The peace process went back and forth because of a divergence of interests and unwillingness to compromise by either conflicting party with respect to the disputed administrative border. For instance, on September 18, 2017, the two regional states reached an agreement to cease any violent action around the border and promised to settle their differences peacefully. However, this agreement did not last more than a day. The Liyu police again perpetrated violence in Chinaksen on September 19, 2017, burning houses and killing civilians who were anticipating a political settlement of the border issues.

The conflict mapping shows that peacebuilding could begin by using customary leaders who are “truly representing” each pastoral group. It also requires that federal forces play a positive role in restraining the Liyu police from either triggering violence or assisting the Somali pastoralists in perpetrating violence, which will in turn help the customary leaders to resolve the conflict and restore peace. Meanwhile, the presence of any armed non-pastoral forces at the border between the two regional states could induce further uncertainty with respect to the behavior of state armed forces, since each of the conflicting parties mistrusts the other. As the narratives have shown, the absence of meaningful action by the federal forces in preventing violence has reduced acceptance of their role by the public.

Institutional Arrangements for Peacebuilding

A distinction must be made between stabilizing and peacebuilding. Stabilizing is a precondition for peacebuilding. In assessing pastoral conflicts in the Horn of Africa, Stephen F. Burgess (Reference Burgess2009) argues that Ethiopia has played a central role in mobilizing military forces toward ensuring stabilization. Nevertheless, peacebuilding efforts have remained sporadic and unsustainable. The peacebuilding processes in East Africa do not often address the underlying reasons for the conflicts, and the state often adopts a liberal peacebuilding approach. In such an approach, the role of the state is to make sure that there is peace in a region or country where citizens respect law and order. Some scholars question whether liberal peacebuilding is a strategic enterprise to contain conflict or if it is able to resolve the underlying causes of conflict emanating from sustained grievances (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Paris and Richmond2009). Stabilization and peacebuilding among pastoralists of different ethnic groups at a local level should be an integral part of a comprehensive institutional framework for ensuring stability in the Horn, based on the IGAD-CEWARN (Intergovernmental Authority on Development-Conflict Early Warning and Response Mechanism) early warning and action systems. Such efforts may include the recognition and strengthening of pastoral self-governance and improved representation of the marginalized pastoral groups in the larger system of governance to enable them to voice their concerns (Burgess Reference Burgess2009). One of the IGAD-CEWARN’s visions is a systematic tracking of political events, an assessment of their trends prior to escalations of violence, and the formulation of options for response that seek peaceful, sustainable resolutions to pastoral conflicts. The CEWARN is essentially designed to support the collection of data on conflicts on a regular basis and the development of preventive measures prior to an escalation of the violence. Peacebuilding efforts at the national level should adopt and operate within this framework.

However, the empirical evidence from Chinaksen and Mieso districts of Ethiopia reveals that state failure to fully adopt the IGAD institutional framework has resulted in a struggle over resources and territories which has become a protracted conflict. During my fieldwork for this article, I found no clear peacebuilding infrastructure in place. No one was accountable for the lives of pastoralists that were lost every day. Even the Pastoral Affairs Standing Committee in the House of Representatives, which is presumed to represent the interests of the pastoralists, was not influential in addressing the underlying causes of the violence. The committee was initially established by Proclamation number 217/2002, with a mandate to respond to and address conflicts and other development challenges in pastoral areas (Mussa Reference Mussa2004). The Ministry of Federal and Pastoralist Development Affairs has failed to take any action toward fulfilling one of its mandates and responsibilities, which was to “facilitate the resolution of disputes arising between regional states.”Footnote 3 Therefore, one can consider pastoral grievance and resource-based violence as indicators of state weakness and fragility in closely monitoring new developments in pastoral areas with respect to the delineation of boundaries.Footnote 4 In addition, the free-riding behavior of political elites who actively wish to take advantage of violence is consistent with the political ecology theory.

All of this cited evidence brings us to the question of how to facilitate a transition from “institutions of violence” to “institutions of peacebuilding,” and how best to identify factors that can enhance the transition.Footnote 5 The underlying question is, what can be done, or what can the Ministry and the Pastoral Affairs Standing Committee (together with other state actors) do to ensure peace between the pastoral groups in the two regional states? The findings of this study suggest four possible avenues to be considered in order to build peace. Each possible action also lists the measures that must be taken to make progress toward peacebuilding.

1) Establishing a mechanism in which the conflicting parties respect the 2004 referendum: The Somali and Oromo had lived together peacefully for years before the outbreak of border violence. They had shared values and systems of conflict management. Peace can prevail only if both parties respect the 2004 constitutional referendum. In particular, the district experts state that the current state intervention should have facilitated this process instead of pursuing a different strategy serving only short-term interests, which involved an attempt at the stabilization and prevention of conflicts. The question of why a new territorial claim was presented in the Somali region after thirteen years was alarming. Most respondents consider the claim to be “unjustifiable by any standard.” Neither the Somali nor the Oromo pastoralists have raised the issue of inclusion into either of the two regions. The territorial claim was perceived to be a political move, where the Somali region brought in new claims which promoted violence.

Moreover, pastoralists indicated that those kebeles which claimed to have been left out during the 2004 referendum (specifically the Chinaksen district) should let their issues be peacefully put to referendum to reconfirm public choice. This is based on the provisions made by the national constitution in Article 48 (sub-article 1) on “state border changes,” which states that “All State border disputes shall be settled by agreement of the concerned states. Where the concerned States fail to reach agreement, the House of the Federation shall decide such disputes on the basis of settlement patterns and the wishes of the peoples concerned.” In a normative sense, the wish of the people is revealed through the votes they cast in a transparent referendum, without any imposition or manipulation. Insights gained from interviews suggest that the national election board needs to recognize the “disputed kebeles in each district,” and address the claims and counterclaims based on provisions made in the national constitution.Footnote 6 This can be followed by an immediate delineation of the boundary based on the outcome of the public vote.

The new political order in Ethiopia initially adopted ethnic-based federalism to enable ethnicities and nationalities to enjoy their long-suppressed cultural and political rights and to ensure unity within diversity, as stipulated in the Ethiopian constitution. The practice of correlating ethnicity with boundaries and the effort to expand territorial control have been central to the violent conflict. Such violence could have been prevented by abiding by Article 48 of the constitution. For the purpose of sustainable peacebuilding, there is now a need to de-emphasize the ethnic-based regional boundaries, as ethnicity itself remains fluid at the regional interfaces between Somali and Oromia due to intermarriage and other longstanding relationships. To the contrary, reinstating a system whereby pastoralists of both ethnic groups honor their traditional resource use arrangements is critical. Along with this, local administrators have expressed the need to ensure the creation of a democratic system for the people’s voice to be heard and their choices to be respected, following the 2004 referendum.

2) Formal recognition of the customary system in conflict prevention and peacebuilding: Insights gained from interviews show that pastoralists of both ethnic groups have a well-established system of managing conflicts over resources, using customary systems practiced by their elders. Peace can prevail through the decentralization of decision-making to the local level, which requires providing support for capacity-building for the resolution of conflicts over resources or territorial units by customary leaders. Some elders provide state decision-makers with distorted information on the conflicts; they hold ambivalent positions and try to benefit from the conflict processes. Meanwhile, pastoral elders of Jarso and Girhi have expressed the need to invest in building trust between both ethnic groups in order to exercise traditional justice, in accordance with their shared cultural norms and social cohesion.

Additionally, security officers suggest an exclusive use of a “community-based policing system” to provide security to the pastoral groups involved in the conflict, in which case decisions by the customary leaders in resolving disputes are enforced by the community police. Some scholars argue that it would be difficult to implement such a system, as the relationship between the state and customary systems is characterized by mounting political uncertainties. There is also a deteriorating legitimacy of the customary leaders among the pastoral communities. For example, the weak and incomplete state presence in addressing cattle raiding and the inability of the customary systems to control such actions have contributed to the violent conflicts (Hagmann & Alemmaya Reference Alemmaya and Hagmann2008). This suggests that the prevailing governance structure must support and reinforce the state-customary relations. The relationship has to be reshaped in such a way that it provides a space for customary leaders to exercise their culturally respected conflict resolution procedures.

To facilitate sustainable peacebuilding, the respondents from both districts emphasized that those “customary leaders who are in the people and with the people” can complement the government’s effort to enforce comprehensive agreements which can prevent violence and build peace. The Somali elders agreed, explaining that customary systems work by means of oath taking (swearing by perpetrators). They break the bones of slaughtered animals, which are dedicated by the perpetrators, at the ritual of reconciliation. The perpetrators express their commitment to peace by reiterating the words of culture: “let God break my bone like this if I happen to breach this agreement.” Breaking promises is expected to cause bad luck in life. Among pastoralists, this superstition embedded in their belief system works effectively in suppressing undesirable behavior that might otherwise trigger violence.

Victims of violence were formerly compensated through a system of compensation, termed gumma (among the Oromo) and mag (among the Somali), in which culturally-based rituals are performed to resolve violent conflicts. Though this practice has been reduced over time due to a weakening of the customary systems (owing to external influence and people’s temptation to resort to formal systems), customary leaders judge such practices to be “much more powerful than the formal court” in preventing undesirable behavior. In this case, the involvement of the state in capacity-building and the elders’ role in peacebuilding is characteristic of hybrid peacebuilding.Footnote 7

3) De-emphasizing the use of military forces to prevent violence: The relationship-mapping process indicates that peacebuilding requires the removal of all state-based armed forces from the border of the two regional states. This was related to the general fear by both ethnic groups that any army at the border may favor one or the other of the parties involved. All national armed forces should be restricted to their mandates of peacekeeping and national defense. They should not interfere in matters related to boundary disputes or internal matters, such as shifting of kebeles into either region, which can be handled easily by employing constitutional provisions. Mediating actors, such as the federal government, need to respect the interest of the people to be governed under either of the two regions. Agreements between the two regional states have often been violated, partly due to the weak nature of law enforcement and reluctance on the part of the federal government. Along gender lines, while men perceive “state failure to build peace and limited commitment of the law enforcing agents,” women still firmly believe that “there is nothing that goes beyond the capacity of the state” to build peace.

There is also a divergence between districts’ experts (civilian) and security forces on the position of the armed groups. While experts have stereotyped the armed groups as “escalators of tension” at the border, the security forces claim that they are protecting incidental attacks. Pastoralists were uncomfortable with the presence of state armed forces at the border. Such understanding confirms the need to quickly shift from stabilization (which is a temporary measure) to peacebuilding, where relevant federal actors develop a comprehensive roadmap toward settling territorial disputes by relying on the constitution (Burgess Reference Burgess2009).

4) Improving transparency, system of governance, and community dialogue: The narratives have shown that the conflicting parties have different demands and goals. Peacebuilding requires that both parties adopt strategies that safeguard the development of trust and dialogue. Evidence from the field confirms that state employees were afraid of reporting issues related to the violent conflict and its impact on their work, citing the sensitivity of the issues. The federal security forces were intimidating them for informing their friends about damages caused by the violence. One of the experts interviewed shared his experience of being kept under police custody upon his return from field supervision in 2016, suspecting that he had leaked information on what was happening to people at the regional border. However, the state media failed to report on the violent conflict at an earlier stage.

Open discussion about the violent conflict has been observed lately following a change in leadership in the Oromia Regional State, which involved the appointment of a new regional president, Lamma Magarsa. He was perceived to be taking a progressive approach and being willing to address public grievance through constitutional means. Pastoral respondents viewed this as a positive move. The experts called for the state authorities to prosecute those who encouraged the violence and to initiate a community dialogue including both Somali and Oromo pastoral groups. This should include the youth, elders, women, and all of the community representatives who have been affected by the violence. Such an all-inclusive community dialogue, as opposed to the previous ad-hoc meetings that were occasional and sporadic in nature, might open up a space for conflict settlement and reconciliation and help in developing a peacebuilding framework that addresses the concern of the wider pastoral groups of both conflicting parties. One of the benefits of dialogue, as identified by the security officers, is that such a platform would help to address the discontent that has been created over the course of conflict management and establish mechanisms for enforcing an inter-regional agreement. Current literature recognizes the power of sustained dialogue (extensive public consultations, workshops, and forums) in peacebuilding efforts where inter-ethnic conflict recurs (Burgess Reference Burgess2009). Such dialogue is perceived to be instrumental in preventing violence from escalating into civil war. It is much more effective than signing an agreement, as it involves a continued engagement of the feuding parties with issues of concern at multiple levels (Lederach Reference Lederach2005).

These four institutional pathways (or mechanisms) toward peacebuilding, identified based on evidence from the field, generally conform to the hybrid peacebuilding approach (Ginty Reference Ginty2010; Richmond Reference Richmond2011; Anam Reference Anam2015). Formal recognition of the customary systems through empowering elders would represent an effort to accommodate local perspectives toward peace. Meanwhile, state intervention to enforce respect for the agreed-upon borders, as drawn during the 2004 referendum, would complement such an effort. At the local level, facilitating community dialogue to ensure transparency by sharing information among all stakeholders (pastoralists and state actors) affected by the conflict would increase the effectiveness of the hybrid peacebuilding approach. As Roger Ginty (Reference Ginty2010) explains, the hybrid peacebuilding approach consists of: (1) the compliance power of the liberal peace in which law and order need to be imposed and (2) the option for the local actors (pastoralists) to resist, ignore, or adopt interventions, based on the principles of liberal peace.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

These findings demonstrate that the political economy and political ecology theories are more powerful than the other available theories in explaining the current violent conflict. While resource scarcity and property rights are slightly useful theories for examining the persisting resource-related disputes, the nature of the violence between the two ethnic groups over territory at the border is best explained by political ecology. Social and political factors are important determinants of violent conflict. The political dimension is manifested through the grievances over the outcome of the 2004 referendum, which has transformed local-level resource-based pastoral conflict into a regional-level border dispute. The deterioration of the security situation at the border between Somali and Oromia Regional States was an indication of the limited commitment on the part of the government in settling the issue through constitutional means. This study demonstrates how political elites have focused on “the rights to territory” and the use of ethnic-based networks, resulting in protracted violence as explained by the greed-grievance argument of the political economy (Collier Reference Collier2006) and political ecology theories, whereby access to natural resources is correlated with race (Robbins Reference Robbins2019). The findings also indicate that local-level relationships between pastoralists of both ethnic groups have been distorted by the politicization of ethnicity, which in turn has served the political elites as a strategy to gain more control over border land.

With respect to peacebuilding, the evidence from the field indicates the existence of customary approaches to peacebuilding at the local level, tensions between customary and state-led approaches, the limitations of customary and state-led approaches, and the need for a hybrid approach to peacebuilding. All of this underscores the need for institutional reform to facilitate sustainable peace. Such reform should pay attention to a careful integration of the four institutional arrangements outlined earlier. These findings suggest that a hybrid peacebuilding approach is more relevant than a simple state intervention using military forces to bring stability and prevent violence temporarily (Ginty Reference Ginty2010; Anam Reference Anam2015). As violent conflict remains dynamic, peacebuilding is a process which requires the systematic engagement of victims of violence from both the Somali and Oromo pastoralist communities in order to create and nurture communal platforms for exchange. For example, community dialogue requires the revitalization of the customary systems, which could otherwise be challenged in the presence of state-based armed forces at the border. This dialogue should emphasize how to recover from the destructive violence, to heal from the trauma of violence, and to restore relationships.

The state governance structure does not support the public choice which was revealed through the referendum. A mistaken understanding by the elites of the causes for the violence has contributed to protracted border conflict. Pastoralists of the two ethnic groups at the border did not raise concerns about territory. The findings indicate that the state structures are inefficient, as they depend on the interests of a few political elites. These structures are easily manipulated by self-interested elites and have remained ineffective in preventing further violent conflict. There was lack of control in the decision-making procedures by the district administrators. Complex customary systems were more stable in comparison with state structures, but they were downgraded by the state.

Therefore, peacebuilding requires a political commitment to work on the revival of customary systems by providing them with legal recognition, and to devise mechanisms to include women and youth in the deliberations. The Ethiopian government should also support efforts by customary leaders by undertaking institutional reforms which would discourage manipulation of these leaders by regional state actors in return for personal benefits. The political reform which began in 2018 has resulted in the prosecution of former political leaders who were suspected to have orchestrated inter-communal violence and involved inter-regional public consultation (to restore peace between the two regional states). Such initiatives must not be merely “ad hoc” measures in order to ensure sustainable peacebuilding.

This study has implications for peacebuilding in pastoral areas of Africa where the use of state armed forces to settle border disputes has produced a counterintuitive result, especially when a country suffers from wider political crisis and there is a high level of behavioral uncertainty among the armed forces. The result suggests that formal recognition of the publicly endorsed customary systems, in order to fill gaps created by state weaknesses, can generate sustainable peace. Such measures should be considered an integral element of national political reform.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was made possible by support from the African Peacebuilding Network of the Social Science Research Council, with funds provided by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Comments of the anonymous reviewers were very useful in improving the argument of the article.