Introduction

There is nobody [else] worth worshipping / There is nobody [else] to ask forgiveness from / There is nobody but You / You are here; You are our Lord / All around the world / A scourge has been dropped upon us / Contamination from place to place / The virus has already killed enough people. (Kingbooking, “Mbas mi” [2020])

As the coronavirus pandemic started to spread worldwide in mid-March 2020, Senegalese musicians began to release an array of awareness-raising songs to engage with the public about COVID-19. After the first case in Senegal was reported on March 2, a flurry of creative endeavors surfaced from Senegalese musicians, with new music videos populating YouTube seemingly every day. The stanza above is an extract from one such song, titled “Mbas Mi,” which addresses a spiritual dimension of the pandemic. The term mbas mi—Wolof for “the epidemic”—also refers to the official government briefings which have aired daily on national television since mid-March 2020. One of the major objectives of these songs was to teach people measures they could use to protect themselves and others against the virus. More importantly, these songs were part of an impressive array of public health announcements that emerged from the national response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As the country closed its borders and limited travel between cities, enforcing a curfew and shutting down markets for sanitization, music circulated on television, radio, and social media to offer lists of symptoms along with techniques for prevention and care. Overall, between March and May 2020, dozens of well-known artists across genres (including Youssou N’Dour, Fata, Viviane, Fou Malade, Awadi, and Baaba Maal) provided support for the national effort. While these songs constituted a public health discourse, they also addressed rumors and untruths about the virus, urged people to stay home, sought answers and solace, praised frontline workers, and grappled with perceptions of the “sinful origins” of the pandemic and possibilities for divine intervention. The significance of these songs and their impact on the general population raise several questions: What are the sociological, political, and historical dynamics that facilitated the emergence of these songs? What do these songs accomplish? How do the songs conceive of the pandemic? Given Senegal’s apparent success in the pandemic response, what positive role might music have played in the public discourse?

Building on Fallou Ngom’s idea of music-derived literacy (Ngom Reference Ngom2016), this study examines how Senegalese artists have used music as part of an arsenal of public health announcements around a coordinated national response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Through these songs, the artists have transmitted “mixed” messages, in which science, spirituality, and active fatalism are seemingly interlaced. Music is an effective tool for public health messaging for two reasons: first, as Ngom and Rudolph Ware note, the millennia-long tradition of West African aural religious education reinforces the local importance of auditory production and dissemination of knowledge (Ngom Reference Ngom2016; Ware Reference Ware2014). Second, scientific evidence demonstrates music’s ability to be used as a memory aid and as a mass pedagogical tool (Werner Reference Werner2018:2; Purnell‐Webb & Speelman Reference Purnell-Webb and Speelman2008; Wallace Reference Wallace1994). As language researcher Riah Werner points out, the “link between music and verbal memory is reinforced by studies that find that recall is facilitated when text is sung instead of spoken, particularly when the melody is familiar or repetitive” (Werner Reference Werner2018:3). Melody (through music) therefore contributes to what we identify as “pandemic literacy”: widely circulated and consistent knowledge about the coronavirus. Though Ngom applies his theory of music-derived literacy to ‘Ajamī poetry produced by Murid disciples in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, he also argues that it is a pedagogy applicable to contemporary modes of knowledge production and acquisition through digital conduits.Footnote 1

In this article, we first outline the Senegalese tradition of using music to respond to pandemic and epidemic situations during the last half-century, placing it within relevant ethnomusicological, anthropological, sociological, and historical literature. Second, we analyze the public health awareness messaging and the function of these songs as “medical” advice, advocating for protective measures to the general public. The article highlights the spiritual and metaphysical connotations of selected songs, as many Senegalese consider the pandemic to be a retributive act of God. Many of these musical productions are permeated by a belief in the coexistence of the spirit and the body, the scientific and the metaphysical, despair and hope, dichotomies which are not mutually exclusive. Particularly applicable, for many Senegalese Muslims, is the idea that divine punishment is often followed by divine recompense. This idea is supported both by Qur’ānic teaching and Wolof proverbs.Footnote 2 Finally, this study delves into the language use and imagery within the songs and music videos.

Our analysis is based on forty-two songs that were released on YouTube, with the bulk of them produced during Senegal’s national quarantine and curfew in late March and early April 2020. The songs represent a mix of genres, including rap, mbalax, Afro-beat, and reggae, among others. These songs are situated within the context of the national strategy against the pandemic that has been enacted by the government, the Senegalese scientific community, and the World Health Organization. In addition to exploring scholarship dealing with past public health crises in Senegal, we also analyze primary sources and data from the Senegalese Ministry of Health related to pandemic management. Recent trends in (ethno)musicological scholarship have called into question the emphasis on context over music (Currie Reference Currie2009; Steingo Reference Steingo2016). In this vein, rather than focusing primarily on artists or production, we critically examine the songs themselves as pedagogical tools.

Senegal’s COVID-19 Response

In March 2020, as the first coronavirus cases were emerging around the world, Senegal’s official response drew on its long history of epidemic management. Preexisting resources included the Protocoles Opérationnels Normalisés EBOLA, a 226-page manual outlining instructions and standard operational procedures for pandemic response, and the Plan Stratégique for general public health emergencies. Based on these manuals, the Senegalese Ministry of Health, in concert with the Health Emergency Operation Center (Centre des Opérations d’Urgence Sanitaire, or COUS), rolled out the centralized pandemic response to COVID-19. They set up call centers to direct symptomatic people to testing locations and the closest designated hospitals, providing quarantine beds in government-requisitioned hotels. Mobile labs and field hospitals assisted with rapid testing and the anticipated large numbers of cases.

On March 9, 2020, the Senegalese Minister of Health, Abdoulaye Diouf Sarr, summoned Senegalese musicians and other artists to a meeting to request their contributions to the awareness campaign. In this meeting, he stated:

The fight against the epidemic is not just the affair of the health sector; it requires an inclusive and multi-sector approach…. Everybody is therefore involved. The longstanding collaboration between the health and culture sectors must not be neglected. Artists, through their songs, sketches, theater performances, and artworks, have always facilitated the awareness-raising campaign, thus helping in behavioral changes and improving public health indicators among the population. (Abdoulaye Diouf Sarr, March 9, 2020)

This is an indication of the intersection between the political and the artistic in public health intervention. Diouf Sarr’s address provided artists with an official governmental commission, requesting their songs as part of the national pandemic response.

The rapid propagation of the coronavirus in March and April overwhelmed some of the most robust healthcare systems in the world, proving that an effective response to a global pandemic does not solely depend on economic and technological capacities. While some industrialized, so-called “Global North” countries such as Italy saw their healthcare systems on the brink of total collapse, the United States and many other countries struggled early on with a comprehensive, coordinated effort to contain the virus. On the other side of the Atlantic, countries such as Nigeria, Rwanda, and Senegal managed to formulate an effective national response to the pandemic, with positive results that have been touted by international institutions such as the World Health Organization. Due to Senegal’s robust pandemic response, neighboring countries Mauritania and the Gambia solicited Senegal’s expertise to help them better manage the spread of the virus in their own countries (Cissé Reference Cissé2020). As journalist Jen Kirby notes, “consistent messaging from government and public health officials helped these efforts” (Kirby: April 28, Reference Kirby2021).

As Judd Devermont, the director of the Africa program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, stated, “Senegal deserves to be in the pantheon of countries that have … responded well to this crisis, even given its low resource base” (Shesgreen Reference Shesgreen2020). A recent analysis of thirty-six countries examined by Foreign Policy magazine ranked Senegal’s pandemic response as second in the world, behind only New Zealand, finding that “Senegal received strong marks for ‘a high degree of preparedness and a reliance on facts and science,’ while the U.S. was dinged for poor public health messaging, limited testing and other shortcomings” (Shesgreen Reference Shesgreen2020). Fourteen months after the beginning of the pandemic, data from the Senegalese Ministère de la Santé et de l’Action Sociale showed that 42,437 COVID-19 cases had been confirmed in Senegal, with 1159 deaths (as of June 2021). Overall fatality has remained at 2.75 percent, with test positivity at 3.2 percent (Ministère de la Santé et de l’Action Sociale 2020).

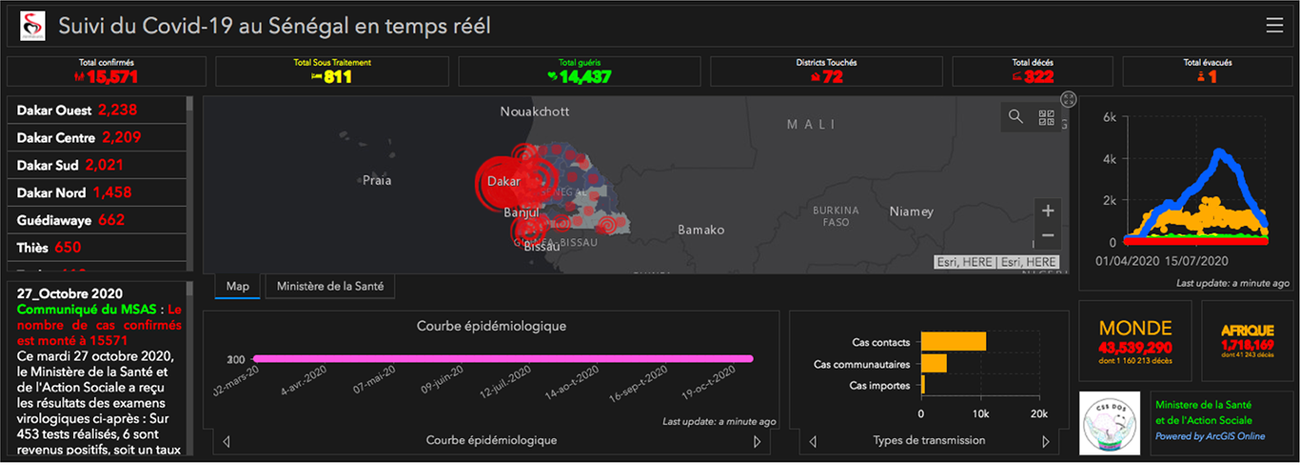

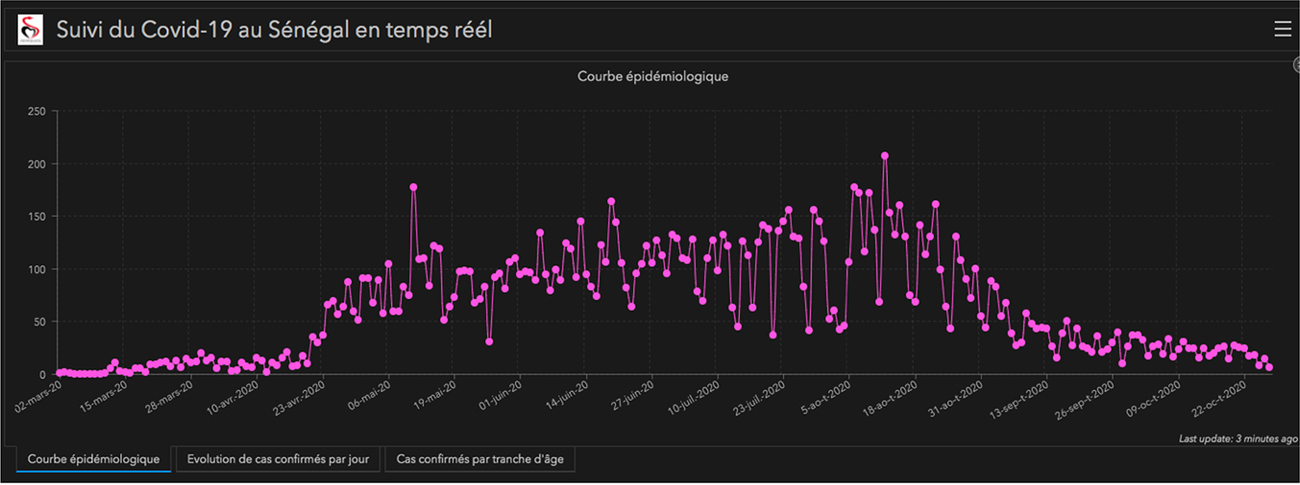

The charts shown in Figures 1 and 2 are partly indicative of the Senegalese government’s commitment to providing transparent and up-to-date data concerning case numbers and fatalities. Some of Senegal’s other strategies cited by international agencies as having had a positive effect on pandemic outcomes include “early and aggressive implementation of preventative policies,” including travel restrictions, a nightly curfew, and closures of businesses for sanitization. In addition to the government’s reliable data and involvement of the scientific community, Senegal relied on public discourse centered around opinion leaders, including musicians, who quickly joined in the response with efforts to educate the population about prevention and care. African musicians have long tapped into this capacity when addressing issues of public health.

Figure 1. Epidemiological chart showing the number of positive cases in Senegal between March and October 2020. Source: Ministére de la Santé de l’Action Sociale.

Figure 2. Interactive chart showing the evolution of the pandemic in Senegal in real time. Source: Ministére de la Santé de l’Action Sociale.

The History of Music and Health Crises in Africa

Popular music has a long history of prophylactic use in public health efforts. While artists in the Gambia, Liberia, and Guinea used music to spread information and prevention tactics about Ebola during the epidemic which lasted from 2013 to 2016 (McConnell & Buba Reference McConnell and Buba2017), a number of ethnomusicologists have also written about the efforts of African musicians in AIDS awareness and prevention (Barz & Cohen Reference Barz and Cohen2011; Kyker Reference Kyker2012) and in public health and sanitation work (Frishkopf Reference Frishkopf2017). Tim Rice has noted that “partly as a consequence of musical interventions in this context, the incidence of HIV/AIDS has dropped significantly in Uganda over the last two decades” (Reference Rice2014:199). In the same vein, Fraser McNeill identifies a dual purpose in “singing songs of AIDS”: first, it “exposes the general public to the safe sex message, fulfilling the obligations of the NGO,” and then it touts “a fluency in biomedical knowledge of the kind which is valued in the public health sector” (Reference McNeill2011:4). Imani Sanga notes that Congolese-born musician Dr. Remmy Ongala advocated condom use through song in the face of the AIDS epidemic (Reference Sanga2010). Austin Okigbo also comments on the multiple functions of songs in South Africa’s AIDS response, in relation to tradition and community links, morality, politics, and the supernatural (Reference Okigbo2017). Historically, Senegalese musicians have participated in this tradition, as they have used music to educate the public regarding epidemics such as yellow fever, tuberculosis, polio, HIV/AIDS, cholera, and particularly malaria.

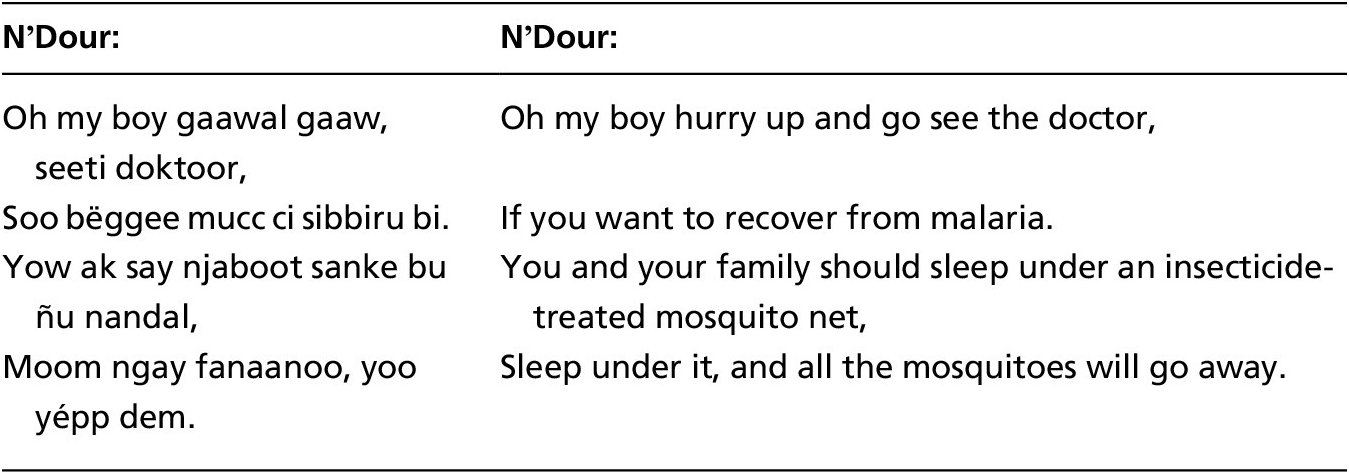

In 2005, Youssou N’Dour and other well-known West African musicians performed at a “concert in Dakar, Senegal, to generate support in the fight against malaria” (Ashenfelder Reference Ashenfelder2007:685). This concert (“AFRICA LIVE: The Roll Back Malaria Concert”) was part of a larger campaign known as Roll Back Malaria (now the RBM Partnership to End Malaria), a global initiative begun in 1998 which was designed to “halve deaths from malaria by 2010” (Yamey Reference Yamey2004). Following the concert, “N’dour and his brother created Senegal Surround Sound, a communication and education initiative designed to reduce the burden of malaria in Senegal,” as well as the 2009 endeavor Xeex Sibbiru [Wolof: Fighting Malaria] (Mouzin et al. Reference Mouzin, Thior, Diouf and Sambou2010:16). Xeex Sibbiru generated a number of music videos, songs, and song competitions throughout Senegal; these efforts were accompanied by a mass distribution of mosquito nets in late June 2009 (AIDS Weekly 2009). In the song “Xeex Sibbiru,” N’Dour advises:

Source: Youssou N’Dour, “Xeex Sibbiru” (Reference N’Dour, Diouf, N’Dour, Faye and Gawlo2009)

In these lyrics, the artist offers advice on protection from the mosquitoes which carry the disease, insisting on the importance of mosquito nets. Senegalese musicians Omar Pène and Fata released a similar song called “Palu” (malaria) in 2002. These songs were very popular, making them recognizable and therefore good material for contrafacta that younger artists used during the COVID-19 pandemic. ZBest Family’s song “Coronavirus” (2020) uses the melody of “Palu,” making it an easily recognizable tune, a memory aid, and a translatable message from one epidemic to the next. Particularly because of music’s ability to act as a memory aid, there is a dialectical link between music and health education.

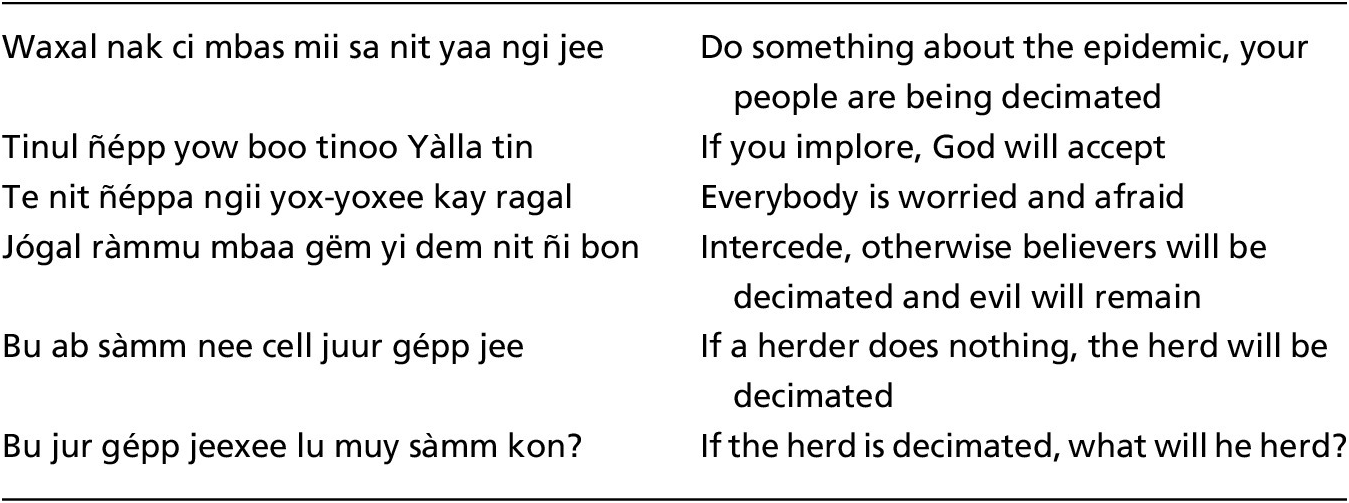

Consistent with this idea is the work of ethnomusicologist Abimbola Cole, who describes “musical arts education [as] capable of conveying health care objectives and details related to psycho-medical care” (Reference Cole, Barz and Cohen2011:145). Similarly, Okigbo analyzes the use of gospel music in the struggle against HIV/AIDS, as well as the long history of music and epidemics in South Africa going back to the influenza pandemic of 1918 (Reference Okigbo2016). In Senegal as well, religious leaders have used chants and sung poetry to address pandemic awareness, suggest prayers, and give ndigël (instructions) for profitable spiritual investments which may have a life-saving outcome. In one of his chanted poems, Muusaa Ka chronicles how Bamba, founder of the Murīdiyya Ṣūfi order, saved Siidi Maabo from the plague as a result of Maabo’s kindness to Bamba when he was on his way to exile (Ngom Reference Ngom2016:138). This constituted a spiritual investment on Maabo’s part, one which was rewarded with protection from the epidemic. Another chanted poem by Sëriñ Mbay Jaxate, one of Bamba’s companions, points to the importance of intercession by the saints, especially during an epidemic:

Source: Excerpt from a Wolof Ajami poem by Sëriñ Mbay Jaxate. (Courtesy of Fallou Ngom)

Chanted poetry is therefore a powerful tool which historically has been used to address public health issues and ask for intercession in times of calamity. It also reinforces the centrality of religious leaders in public affairs.

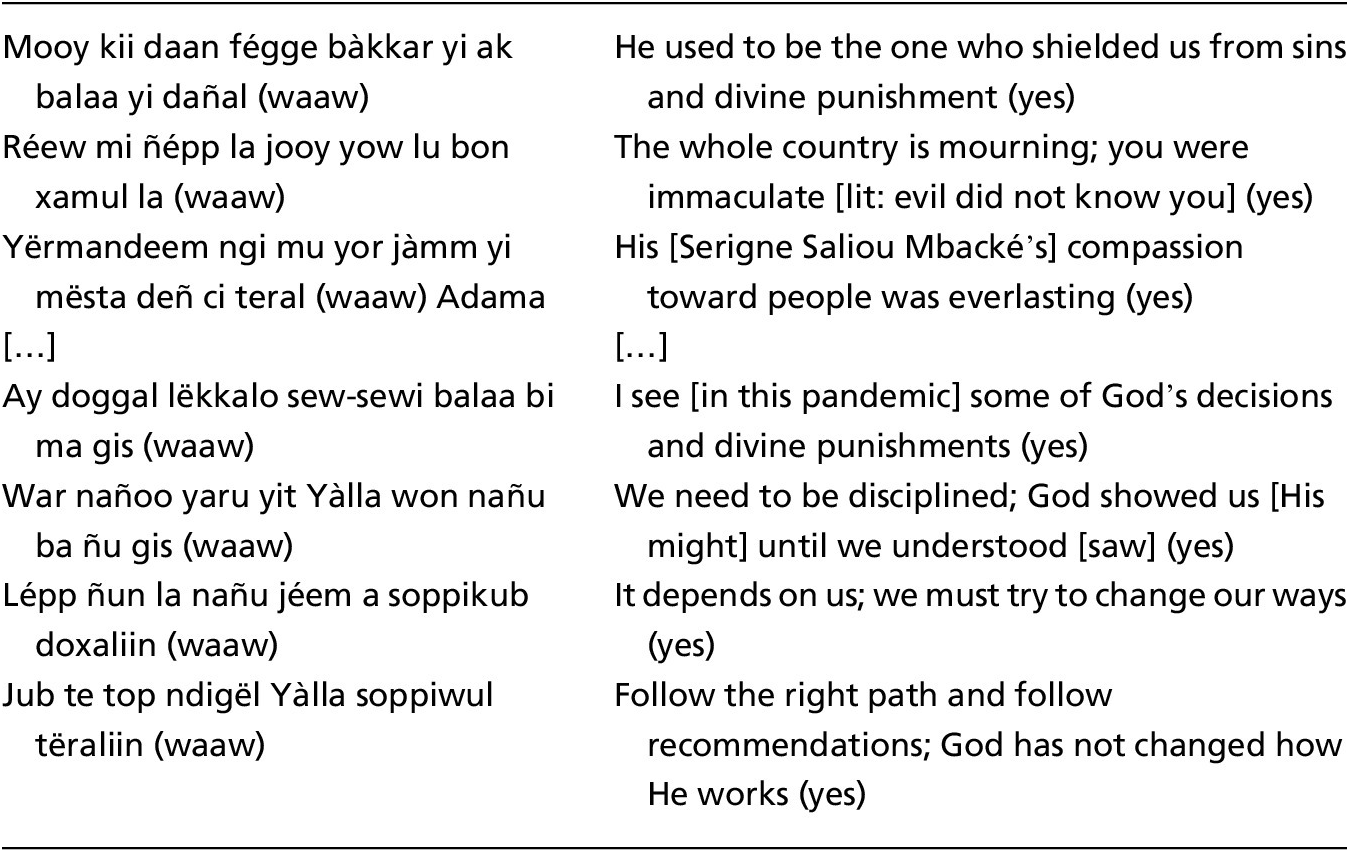

In Senegal, pandemic management has never been solely the affair of the state and elected public officials. It also involves artists, athletes, civil society, and religious leaders and organizations. The involvement of the latter is especially important, as during colonial times, religious leaders constituted an essential link between the authorities and the population at a time when healthcare facilities and services were poorly developed. In 1918, for instance, El Hajji Malik Sy, leader of the Tijaniyya Ṣūfi order in Senegal, was instrumental in a public health campaign during a plague outbreak. When the disease threatened to infect the colonizers, the colonial administration, led by William Ponty, attempted to move a segment of the indigenous population to a newly created isolation village, initially called Ponty Village. However, Senegalese historian Mor Ndao writes that there were violent protests because the population did not want to be displaced or vaccinated; they argued that the vaccine was a form of vengeance because of the earlier election of Blaise Diagne in 1914 to the French parliament. It was the religious leader El Hajji Malik Sy who negotiated with Governor Ponty, convinced the population to move to the isolation village (which he renamed Médina), and volunteered to be vaccinated as an example to his followers (Reference Ndao2015). While El Hajji Malik Sy physically intervened between the colonial government and the population, there is a second type of intervention common in local discourse about catastrophes, which is spiritual intervention by saints between the population and God, especially in order to gain protection from divine punishment (Ndao Reference Ndao2015). Descriptions of such intercession are prominent in music produced about the novel coronavirus in Senegal. In his music video for “Fagaru” (“prevention”), religious singer Mouhamed Rassoul Niang visually gestures toward a picture of the late Khalif Serigne Saliou Mbacké, as he sings a description of intervention in call-and-response, saying:

Source: Mouhamed Rassoul Niang, “‘Fagaru’ COVID-19” (Reference Niang2020)

Not only do these quoted lines allude to a metaphysical origin of the pandemic, but they also associate protection from it with the intercession of saints such as Serigne Saliou. Niang’s song is marked by its vocal style, prominent within Murīd circles (and specifically within the Baay Faal community, a sub-group of Murīdiyya), which uses a ndënd (percussive instrument) but no other melodic instruments, and a call-and-response interaction between the woykat (lead singer) and awwukat yi (the chorus). The hagiographic style refers to a type of song typically used to praise saints, the Prophet, or other religious leaders. The sound of the song itself carries spiritual authority, and therefore lends extra legitimacy to Niang’s text from a religious perspective. Along with his religious advice, Niang’s song also provides instruction for preventive measures, serving to educate his audience.

COVID and Music-Derived Literacy

In times of crisis, music has been used not only as a ludic tool, but also for didactic functions. This is all the more evident in the case of COVID-19, as Elise Cournoyer Lemaire notes in the Canadian Journal of Public Health: “Music constitutes a resource that allows for rapid and massive transmission of information to a variety of audiences” (Reference Cournoyer Lemaire2020:479). Although much ethnomusicological scholarship is critical of claims of music’s universal application(s), studies in the field of psychology have suggested some type of “universal” emotional response to musical stimuli, as well as local and frequent engagement with music in contemporary everyday life (Egermann et al. Reference Egermann, Fernando, Chuen and McAdams2015; Greasley & Lamont Reference Greasley and Lamont2011).Footnote 3

In Senegal, health authorities enlisted the aid of artists, using the ability of music to transmit information to popularize their message and increase their audience base. The use of music as a literacy aid also has deep roots in local religious communities. Linguistic anthropologist Fallou Ngom has described a phenomenon within the Murīd Islamic communities in Senegal, wherein sung poems, also known as Xassida, are used to teach classical Arabic and ʿAjamī literacy.Footnote 4 Ngom notes that music “is a primary channel of acquisition of literacy,” since from the

early days of the Murīdiyya, as peasants and herders heard the songs composed by Bamba and his ʿAjamī masters, they learned about the ethical, spiritual, pedagogical, and ideological underpinnings of the movement, memorized some songs, and gradually learned to decipher the Arabic and ʿAjamī orthography in the lyrics they had memorized. (Ngom Reference Ngom2016:33)

The roots of Ngom’s music-derived literacy additionally reach into the history of Islam itself, since “the Qur’ān is regularly read and recited in Murīd communities as in any Muslim community,” and as Ngom points out, the original revelation of the Qur’ān to the Prophet was also received aurally (Ngom Reference Ngom2016:33). Through the process of music-derived literacy, Ngom highlights that not only is music a means for the acquisition of knowledge, but it is also a way to learn skills (in this case, reading and writing a different language). Music about COVID-19 functions in a similar way, and with similar goals: to broaden the knowledge base of the general population in the language of this specific virus and its symptoms and treatments. The music, in effect, provides a specific type of literacy.

With respect to the music produced during the early days of the pandemic, music-derived literacy is effective for several reasons. First, for the nearly seventy percent of the population that does not necessarily read or write French (the official language of the country), many of the songs we analyze constitute a valuable source of information about treatments, lists of symptoms, and instructions for what to do when experiencing them in a variety of local languages. In this case, music acts as a bridge between the population, the government, and the scientific community, allowing for easier access to information. These songs are predominantly in Wolof, but some also provide information in the other national languages of Senegal, including Joola, Séeréer, and Pulaar; French and English also have limited representation, targeting foreigners living in Senegal who may not speak local languages. The polylingual nature of the songs provides an inclusive method of communication for health concerns related to the pandemic. In other words, this music helps the general population acquire a specific type of literacy around COVID-19—what we could term “COVID-literacy.” This literacy was urgently needed at the beginning of the pandemic, since the novel coronavirus might initially have symptoms similar to the flu or the common cold. The contributions of musicians to the dissemination of knowledge helped to quickly educate the population in three specific areas: prevention, symptoms, and instructions for how to proceed if symptoms should appear. One important aspect of this type of music-derived literacy is the consistency of the information provided through the songs. All of the songs we analyze give the general population clear and consistent instructions—endorsed by the Senegalese scientific community—for how to respond to the virus.

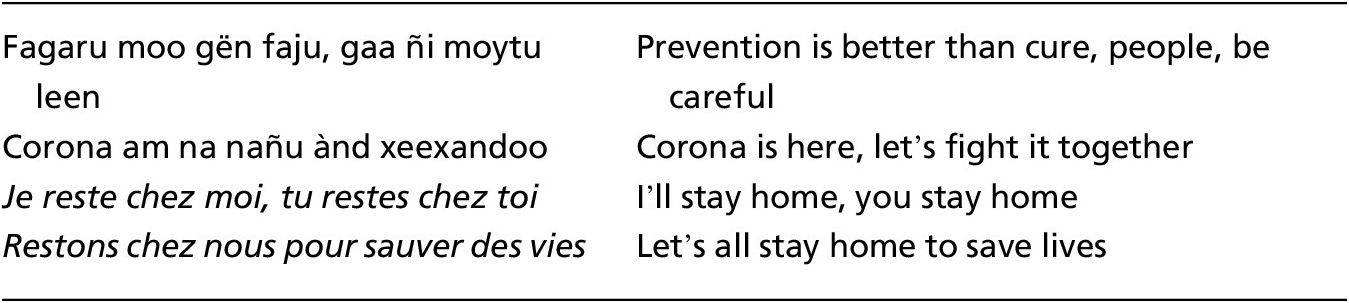

Being COVID-literate in Senegal means knowing first how to protect yourself and your family from the virus; these preventive measures include masking, wearing gloves, coughing and sneezing away from others, staying home, and respecting the curfew from eight o’clock at night until six o’clock in the morning. In the song entitled “Nooy Moyto Corona” (How to Avoid Corona), Senegalese artists Bass Thioung and Bril emphasize (in both Wolof and French) the importance of social distancing and staying home for limiting the spread of the virus:

Source: Bass Thioung and Bril, “Noy Moyto Corona” (Reference Bril2020)

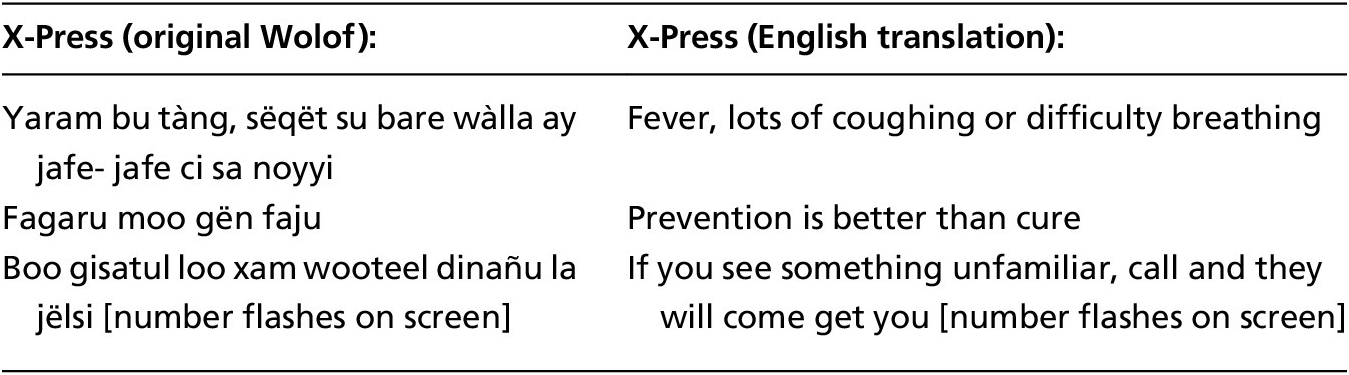

Second, COVID-literacy involves knowledge of the symptoms of COVID-19: loss of sense of smell and taste, headache, cough, and fever. Almost all of the songs involve sections which list at least some symptoms. For example, in hip-hop group X-Press’s song “Fagaru (Si Coronavirus Covid-19)”—a contrafactum of their 2014 song “Réer” (Lost)—the group gives a list of symptoms associated with the novel coronavirus, according to health authorities:

Source: X-Press, “Fagaru (Si Coronavirus Covid-19)” (2020)

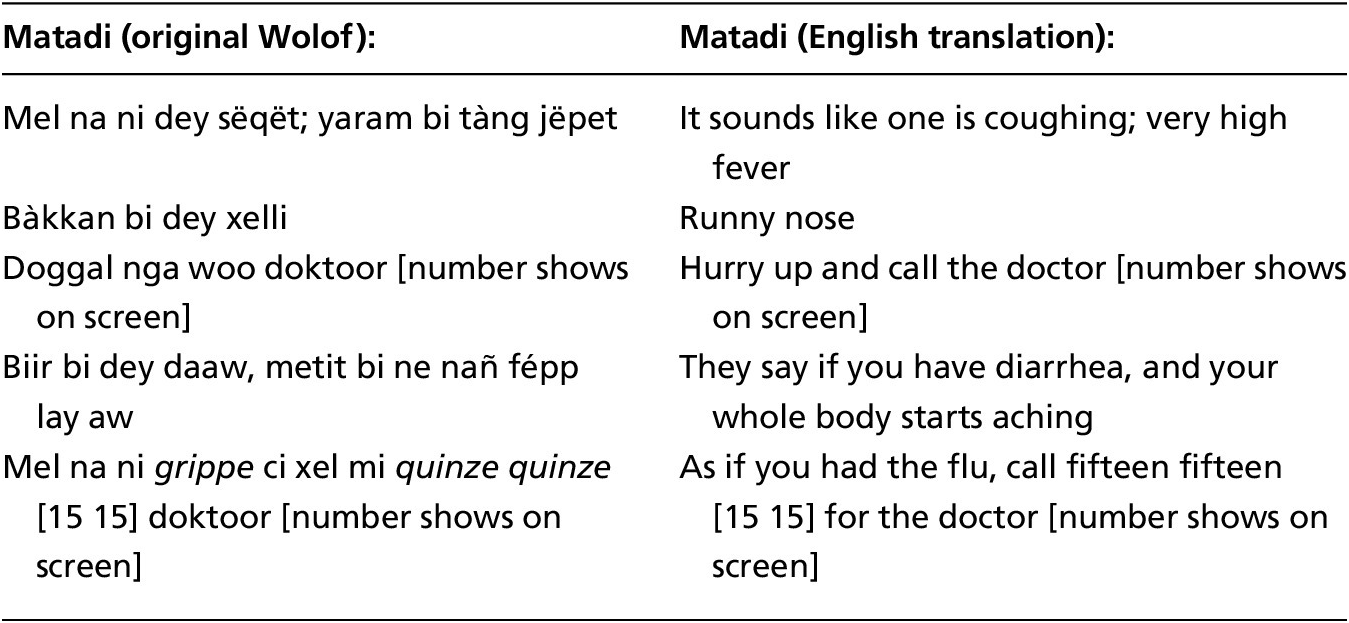

In the same verse, X-Press alludes to one of the most important tenets of COVID-literacy: how to contact health authorities if symptoms appear. The national government set up hotlines for reporting such symptoms. The hotline is the central point of access for all of these services, and the number(s) make appearances visually, in music videos, but also audibly in the songs. The rapper Matadi gives one of the numbers aurally in his verses in the collaborative song “Covid-19”:

Source: Matadi, “Covid-19” (2020)

Singing the phone numbers within the song becomes an effective rhetorical act, increasing accessibility for those who are visually impaired and can’t see the number on the screen, as well as for those who are hearing the song over the radio. One cannot help but notice the insistence on the toll-free number, a way for artists to ensure that their audience understands what to do when symptoms appear. In this sense, vocalizing the numbers underscores the linguistic conflation of the concepts of hearing and understanding in many West African languages; in Wolof, dégg can mean both “to hear” and “to understand” (Ngom Reference Ngom2016:30). Many of the songs use repetition to emphasize important elements. Afro casa’s song repeats the toll-free number three times, following a list of symptoms, using repetition as a pedagogical tool.

Source: Afro casa, “Coronavirus sensibilisation” (Reference casa2020)

Calling prompts one of several responses: an ambulance might be sent for a suspected patient, taking them to a location where they can be quarantined and tested, a health official or a mobile lab might be sent to perform a test on site, or the family might receive further instruction for what to do next. The publication of phone numbers by musicians in their music videos aids in the rapid dissemination of information, leading to a coordinated and predictable response. This response involves COUS, who maintain that their goal is to guarantee a bed for every COVID-19 patient, no matter how mild the case, in order to isolate them and prevent the virus from spreading among families and community members (Shryock Reference Shryock2020). Some artists, such as Y en a marre, worked hand in hand with the Ministry of Health and COUS to produce prophylactic videos to help with the campaign (See Figures 1 and 2).

Finally, another important aspect of COVID-literacy is refuting misinformation—which was common in the beginning of the pandemic—such as the widely circulated idea that Black people were immune to COVID-19 because Black bodies were inherently stronger than white bodies and would therefore be less susceptible to the novel coronavirus. Musical COVID-literacy worked to dispel these beliefs about who was at risk. Many of these songs address this specific false claim, breaking down ideas of fundamental biological difference and emphasizing that the virus could affect any body, regardless of class, race, gender, religion, or national origin. Ombré Zion offers the following line in the collaborative song “Covid-19”:

Source: Fata et al., “Covid-19” (2020)

In the same song, Ngaaka Blindé adds:

Source: Fata et al., “Covid-19” (2020)

Dip Doundou Guiss addresses the same piece of misinformation after providing a list of symptoms in order to deliver scientific context:

Source: Dip Doundou Guiss, “Ànd Xeex Coronavirus” (Reference Guiss2020)

In summary, musical COVID-literacy in Senegal centers around four major points: prevention, symptom recognition, contact with health authorities, and dispelling misinformation. Many of these tenets of COVID-literacy have been applicable to other local health crises; songs about malaria from previous decades likewise addressed misinformation in the community, as well as symptom identification and instructions for seeking care. Senegalese musicians were therefore able to draw from a preexisting repertoire of songs on health education when producing songs on COVID-19. Some artists, such as Youssou N’Dour, Viviane, Awadi, Fata, Fou Malade, and Baaba Maal, had themselves already produced or collaborated on songs about previous health crises in Senegal. This lineage of songs about epidemics and public health is perhaps what allowed contemporary artists to produce such a massive number of songs so quickly. In this way, musicians are working in parallel with the Senegalese government which, having recently dealt with the Ebola epidemic, already had measures in place when the novel coronavirus appeared. Rather than starting from scratch, musicians also had an existing template of songs crafted during previous health crises. While science is central to the understanding and messaging about pathologies, many communities also believe in non-scientific origins, explanations, and cures for diseases. Therefore, attacking a pandemic from a united medical, metaphysical, and religious front is vital. Many of the songs mention prayers and other spiritual prescriptions in order to protect oneself and one’s household against the disease. More importantly, they also mention the pandemic as a divine punishment for human sins and nonconformity to spiritual morality.

Music and the Metaphysics of Epidemics in Senegal

The belief in a divine force as the cause of a health crisis suggests a connection between the spiritual and the corporeal; in this epistemological understanding, physical ailments can have metaphysical causes and cures. This spiritual perception of disease has a deep socio-local history. In discussing the cholera epidemic in northern Senegal in the mid-nineteenth century, historian Cheikh Anta Babou notes that the Muslim leader “Amadu Sheikhu […] in the wake of a cholera epidemic in Fuuta Tooro […] viewed the epidemic as a punishment that God sent to Muslims for their sins and for tolerating the occupation of their land by infidels” (Babou Reference Babou2007:29; Pam Reference Pam2018). The late historian Lamin Sanneh has likewise noted a history of faith healing among West African Christians, particularly during the 1918 influenza epidemic (Reference Sanneh2018). Historian Myron Echenberg has catalogued songs in the Séeréer community grappling with the loss of relatives and loved ones during the bubonic plague outbreak in the mid-1910s. One song in particular, composed by Coumba Gaye, addresses the perceived causes of the plague, hypothesizing that a local woman, Yaa Man-ce, had transgressed Séeréer “codes of conduct” by bringing food from outside of the quarter to a pregnant woman; this transgression was responsible for the deaths by plague of both the pregnant woman and Yaa Man-ce: “Yaa Man-ce has brought unhappiness to the home of Baa Mbeet. She has not been spared since she was brought down at Ba’jataa where she was buried. Being taken to the lazaretto is better than contracting plague” (Echenberg Reference Echenberg2002:178). Contemporary songs concerning the coronavirus pandemic echo the metaphysics of Coumba Gaye’s song, searching for a supernatural cause, and therefore, perhaps, a remedy for senseless illness and death. Interestingly, Coumba Gaye identifies the supernatural and non-adherence to a moral code of conduct for divine punishment resulting in death by disease.

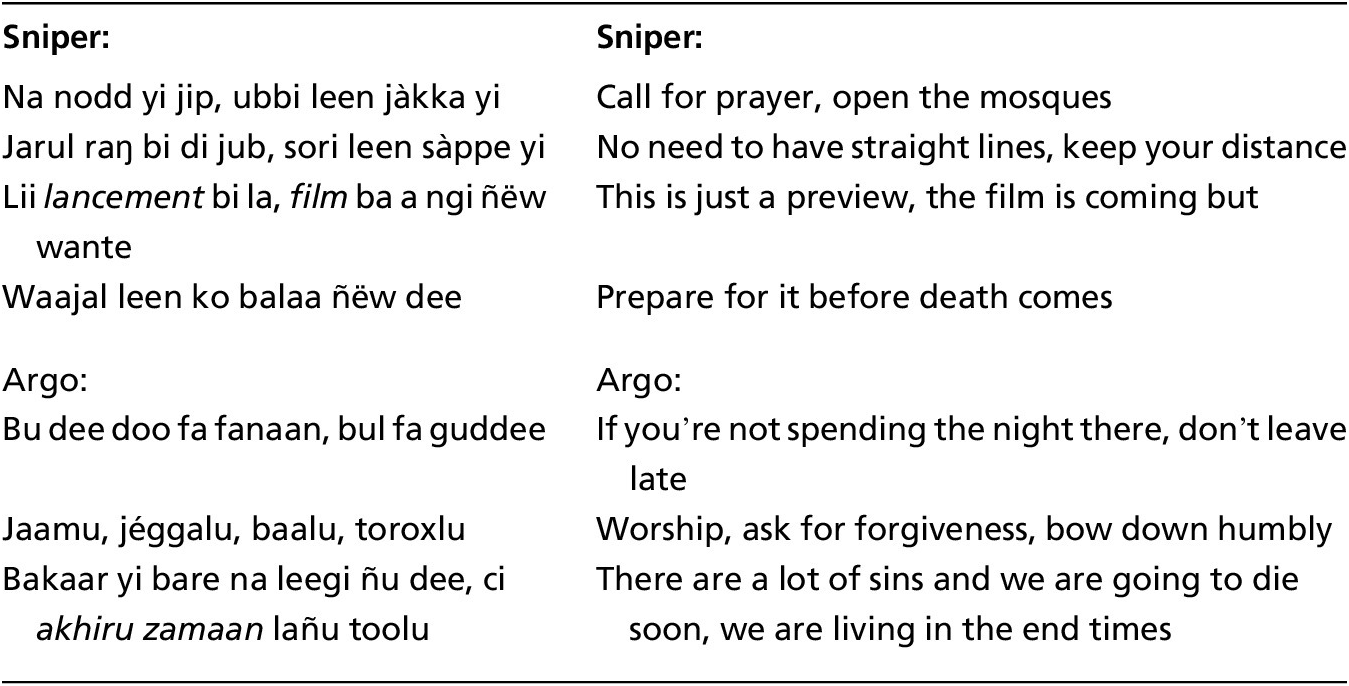

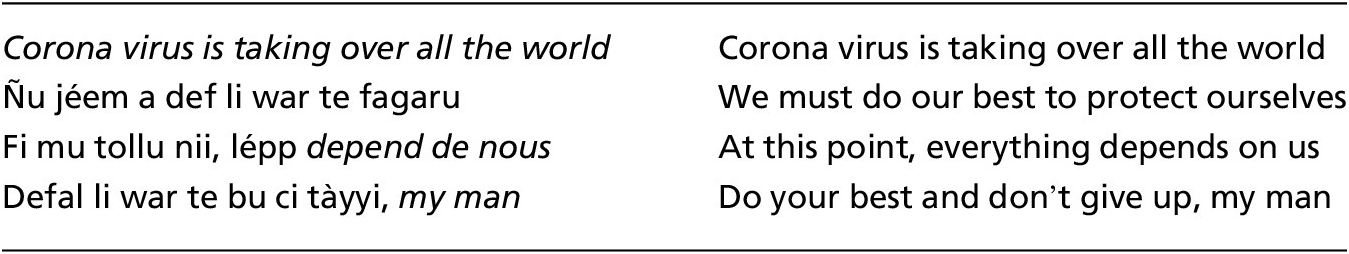

Although many of the songs we surveyed point to scientific prevention measures, symptoms, and instructions for how to proceed, many artists also identify human behavior that is contrary to divine recommendations as the core cause of the pandemic. In the song “Mbas mi” (“The Epidemic”), rappers Sniper and Argo note:

Source: Kingbooking, “Mbas mi” (2020)

The use of the imperative in the first two lines of the lyrics indicates a pressing call for people to return to their Muslim faith and practice, and to pray for forgiveness and deliverance from the pandemic. Similarly, the use of the imperative metaphor bu dee doo fa fanaan, bul fa guddee (“If you’re not spending the night there, don’t leave late”) suggests an urgent call to believers to examine their actions and immediately stop sinning before it’s too late, as the world is nearing its end. This type of rhetoric recurs in many of the Senegalese songs produced during the pandemic, and it reflects a popular mindset that tries to draw causality between calamities and human actions. As Senegalese philosopher Assane Sylla notes in his book La philosophie morale des Wolof (Moral Philosophy of the Wolof):

The Wolof people easily forge causal links between accidents, natural calamities, failures and the immoral conduct of individuals. That a fire devastates a neighborhood, that an epidemic breaks out, that the drought compromises harvests, it is above all the fault of those who indulge in debauchery. (Sylla Reference Sylla1978:61)

Sylla’s statement highlights two important factors: first, that humans must accept that a superior force can determine their destiny, and second, that human actions are always the origin of divine punishment. In other words, devastation, whatever its nature, is God’s reaction to human sin. Sylla’s statement evokes the concepts of passive and active fatalism, the latter of which Senegalese philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne defines as follows: “Active fatalism consists in believing, as is said, in one’s own destiny, in believing that one’s action coincides with that of the pen that writes what must be, since one is oneself the pen and the ink that trace this destiny. This is the fatalism of men and women of action” (Reference Diagne and Adjemian2018:89). Diagne goes on to say that passive fatalism, by contrast, allows no creative flexibility—even for God himself—in decisions relating to everyday life. It should be noted that, when we talk about fatalism, it is not meant to refer to what German Enlightenment philosopher Gottfried Leibniz mischaracterized as fatum mahometanum (Islamic fatalism), or the belief in a predestination “marked by a blind fatalism anchored in the belief of an already-written destiny” (Diagne Reference Diagne2009:86).Footnote 5 According to Diagne, Leibniz based his idea of fatum mahometanum on an unfounded example of Turks who remained in places infected with the plague.

Diagne points out that Leibniz ignored an ambiguous oral tradition which has several versions; in the most complete, the second caliph of Islam, ʿUmar, learned that the plague had descended on a town in Syria to which he was traveling, and he halted his travel plans. When his companion, Abu Ubaydah ibn Al-Jarrah, challenged his decisions by invoking an act of God (fate), ʿUmar responded to him that it was reported (by Abd Al-Rahman ibn Awf) that the Prophet said, “If you are planning to go somewhere and hear that the plague has broken out there, don’t go; but if you are already there, stay and don’t leave the place” (Diagne Reference Diagne2009:90).Footnote 6 ʿUmar, therefore, relied on what Diagne identifies as active fatalism: acknowledging that there are things out of human control, but that humans also have free will, an agency which allows human action to potentially change destiny. For Diagne, active fatalism then becomes the standard; it is not an unchangeable predestination, but rather a fatalism wherein the actions of humans, and changes to their behavior, ultimately both matter and make a difference.

The significance of this concept lies in the fact that in the overwhelming majority of the songs relating to the current pandemic, the artists paint the pandemic as an act of God (ndogalu Yàlla or balaa), but one which can be remedied by following the recommendations of scientists and the Ministry of Health, and by changing “moral” behavior. In these songs, active fatalistic belief transpires through the intersection of faith in a higher power (Allah) and the faith in human proactivity. One example can be found in the hip-hop artist KeiDjily’s song “Fagaru Gënë Fadjû” (2020); KeiDjily notes that the pandemic is pexe jaam la ndogalu buur la; fagaroo gën faju (human action [of the servants of God] and an act of God; prevention is better than cure). Even though the artist believes in the divine origin of the pandemic, he calls for proactivity on the part of the community. Furthermore, the use of “ndogalu buur/Yàlla” (act of God) along with “balaa” (scourge; calamity) and “fagaroo gën faju” (prevention is better than cure) are leitmotivs in the body of songs. The duality between the expressions reflects the core of active fatalism, where faith in God and agential proactivity do not cancel each other out.

Active fatalism in the songs addressing coronavirus not only hearkens back to Islamic tenets, but also to a rich history of popular Wolof proverbs. These proverbs function not only as philosophical and moral lessons, but also as a viaticum, to guide individuals in their life’s journeys (Sylla Reference Sylla1978). Sylla identifies one proverb in particular which resonates with Diagne’s active fatalism: “Yàlla, Yàlla bey sap tool,” which Sylla translates as “hope in God, but cultivate your field.” He goes on to say that “Divine Providence is real, but we must not remain inactive and wait for it to solve all problems. Thus, the Wolof do not admit fatalism or predestination. For them, man has his own efficiency to which is added the help of God” (Sylla Reference Sylla1978:51). These songs reflect two complementary aspects of active fatalism; on the one hand, they acknowledge the ultimate power of God in this situation. On the other, they also recognize the transformative power of the individual and the community to change the outcome of an “act of God” through preventative measures and prayers.

Mouhamed Rassoul Niang’s song provides a potent lyrical example of this type of fatalism. The artist points out that the pandemic is a balaa (scourge), but he goes on to assert that lépp ñun la, nañ sòppi doxaliin (it’s all on us, let us change our ways); the response to his lines is a chorus providing the anaphor fagaroo ngee (here is prevention) throughout the second section of the song. Niang’s song also includes a well-known adage which appears in almost all of the songs: fagaru moo gën faju (prevention is better than cure)—a rallying cry for proactivity.

COVID-literacy in Language and Images

One of the outstanding characteristics of Senegal’s COVID music catalog is the diversity of the languages used. Artists mainly sing in Wolof, but they also use other languages, such as Pulaar, Joola, Séeréer, Saraxulle (Soninké), Bambara, English, and French. The variety of the languages used ensures broader audience accessibility, given the presence of a large foreign population in Senegal and the ethnic pluralism of the country. For example, the song “Stop Coronavirus” by Guinean artists living in Dakar is composed in French and Fulani, as is Baaba Maal’s “Jam Leeli, Jam Yo.” Likewise, Simon Sene’s “Sayo Corona” addresses his audience in Séeréer. Naturally, this ethnic pluralism is reflected in linguistic plurality, with much of the population fluent in more than one language.

Moving a cosmopolitan nation toward COVID-literacy necessitates communication not only using languages which are accessible to a large segment of the population, but also engaging in polylinguality within individual songs. Traditionally, Senegalese music employs an amalgamation of several languages, notably Wolof, French, English, or what Ngom calls “Wolofranglais,” but other languages, such as Arabic, Pulaar, and Séeréer, also appear in the context of musical productions (Ngom Reference Ngom2012:111).

The use of polylinguality within individual songs might be an artistic choice (since more available words increase the possibilities for rhyming or rhythmic structures), but it is also a political decision or strategy to make sure that the overwhelming majority of the population understands the message and moves toward COVID-literacy. This explains the government’s daily briefing being delivered in Wolof (which is spoken by more than 80 percent of the population) and French, but with commentaries in the six national languages (Wolof, Séeréer, Pulaar, Mandinka, Joola, and Soninké) (Cruise O’Brien Reference Cruise O’Brien1998:41). This is a strong attempt at inclusivity, both on the part of the artists and the government; it is particularly critical because a lack of inclusivity could be deadly during a pandemic. In the collaborative song “Daan Corona” (Defeat Corona), hip-hop artist Awadi (Positive Black Soul) and Simon Kouka deliver their verses in French (Didier Awadi Reference Awadi, N’Dour, Korka, Blinde and Viviane2020). Similarly, while Thione Ballago Seck uses a mix of Wolof and French in his song “Corona,” other artists (such as Clayton Hamilton and Matador) choose to use a mixture of English and Wolof:

Source: Clayton Hamilton, “Covid-19” (Reference Hamilton, Awadi, Sene, Bakhaw, Blindé, Adiouza and Matadi2020)

These lyrics illustrate a phenomenon common in the COVID-catalogue: interaction between several languages within a single stanza. This polylinguality has several benefits beyond the inclusivity discussed above. First, it facilitates rhyming, as the artist engages with a larger champ lexical, which can be heard above with Hamilton’s rhyming “fagaru” (Wolof: to prepare/to prevent) with the French word “nous.” Second, as Catherine Appert notes, rapping in English can signal a “sonic zoom, reaching across the Atlantic to a US hip hop tradition” and therefore solidifying affective ties within a trans-Atlantic hip-hop community (Reference Appert2019:161). Finally, the use of multiple languages signals an impressive linguistic competence which is uncommon in even larger musical markets like those in the United States or Europe. It may also point toward a high level of education, cosmopolitanism, or international mobility, all of which can boost a musician’s reputation and marketability. In summary, language use is determinant in achieving COVID-literacy as well as in fighting the pandemic. One of the ultimate goals of the artists and the government is for people to understand the message of how to collectively eradicate the virus. Therefore, another significant aspect of these songs is the “dramatization” in the music videos which accompany them.

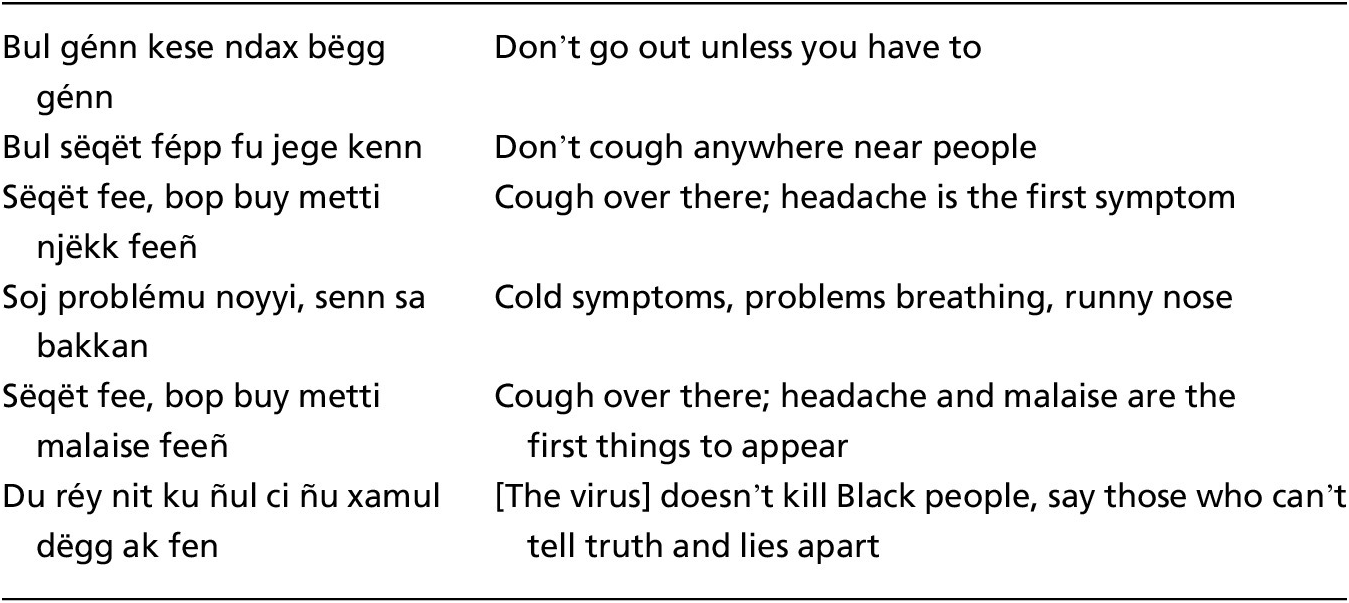

Many of the songs surveyed use graphic video footage of overcrowded hospitals, body bags and gurneys in Italy and France, and (in one case) a coffin wrapped in plastic reminiscent of the recent Ebola outbreak (see Figure 3). Several videos display a photo of the late Pape Diouf, the first Senegalese casualty of the pandemic and a well-known president of the football club Olympique de Marseille. There is an element of shock in the use of this footage; by displaying the faces of the dead and the consequences of the pandemic, perhaps the public can be warned into respecting the quarantine, maintaining social distance, and taking preventive measures. In other words, the artists use an alienation or defamiliarization effect to discourage their audience from engaging in irresponsible behaviors.

Figure 3. Rappers from the Y en a marre movement, wearing personal protective equipment and handing out masks in the streets of Dakar, in their music video entitled “Fagaru Ci Coravirus.” Source: Y en a marre “Fagaru Ci Coronavirus,” 2020.

While the videos discourage irresponsibility through shocking imagery, they also encourage responsible prophylactic actions, for example, by showing footage of Senegalese President Macky Sall washing his hands. Indeed, many of the artists themselves model hygiene, wearing hospital-grade masks and latex gloves. The songs also offer praise for the work of healthcare professionals on the front line, focusing on the image of Professor Moussa Seydi, the head of infectious diseases at Fann University Hospital in Dakar and a key member of the coronavirus task force. Seydi and his team have been hailed as heroes in the fight against COVID-19 in Senegal, but they were also the ones to treat Senegal’s only case of Ebola in 2014. Seydi’s media interventions about the virus are well-followed, as he insists on the importance of prevention to avoid a situation similar to Italy, France, or the United States (Soumaré Reference Soumaré2020). Interestingly, many of the music videos are accompanied by a series of images containing detailed written instructions identical to those displayed in doctors’ offices and hospitals. The videos effectively take the interior of the hospital to the streets—an important consideration when hospitals, preparing for an influx of coronavirus patients, may be inaccessible. Such images reinforce the tenets of COVID-literacy which, in order to be effective, must be aurally and orally accessible as well as visually didactic.

Although interviews with the public about the reception of this didactic musical genre are beyond the scope of this article, the YouTube comments provide cursory information about how the songs have been received. Comments regarding the songs have been overwhelmingly positive and encouraging. Some recurring comments assert that the role of the artist is to raise awareness; one commenter wrote on Dip Doundou Guiss’s video Le vrai rôle d’un rappeur: sensibiliser (“The true role of a rapper: to raise awareness”). Other comments reinforce the messages of the songs, encouraging the public to stay home or take precautions, or to offer prayers. On Mouhamed Rassoul Niang’s video, one commenter offered Yalnafi Yalla dieulé corona bi balla magal Touba (May Allah wipe out coronavirus before the Magal [religious pilgrimage] in Touba). Many of the comments for the religious songs, such as Niang’s, contained the Arabic word machallah, which can be an expression of joy and thanks, but which is also considered protection against the evil eye. Negative comments were extremely uncommon. In fact, we only found one, and it referred to the artist’s activism rather than to the actual message of the song.

Conclusion

As Senegalese artists tap into a history of music and disease awareness with both scientific and metaphysical content, they contribute to a coordinated response beyond just the endeavors of scientists and medical professionals alone. In the early days of the pandemic, when there were many unknowns about the virus, literacy constituted the cornerstone of Senegal’s national response, which exceeded all pessimistic predictions and continues to be cited as a positive example worldwide. Thanks to a coordinated effort on the part of the Senegalese government, religious leaders, civil society, and artists, information about the coronavirus has spread rapidly, and misinformation was quickly addressed to avoid confusion among the population. Senegalese artists made sure that their music became one of the conduits through which COVID-literacy was achieved. Africa in general and Senegal in particular have a long history of educating their populations about disease through music. This strategy has been prominent in the fight against malaria, HIV/AIDS, polio, plague, flu, and other pathologies. Therefore, pandemic music-derived literacy is a powerful and respected weapon which Senegal reinstated to strengthen its national response to COVID-19. Over a span of two months, Senegalese artists (solo and in collaboration) produced nearly four dozen songs addressing prevention measures, symptoms, and the officially recommended course of action in case of infection. Furthermore, many of the songs are infused with a dose of spirituality, whereby artists use metaphysics to explain the origins of pathologies while advocating for intercession and reliance on a higher power to fend off disease. In fact, many of the songs conceive of the pandemic as a divine punishment for human immorality. This spiritual, metaphysical perception also has deep roots in Senegalese history during times of illness. In both the cholera outbreak in nineteenth-century Fuuta Tooro and the plague epidemic in the early twentieth century, historians have noted metaphysical justifications for the disease.

Within the current pandemic, one of the prominent musical features of the songs is the plurality of the languages used within them, which resonates with Senegal’s multi-lingual population. The plethora of languages within the songs ensures that the content has a wide reach, and the music videos enable further accessibility through the usage of shocking and dramatic imagery to draw the audience’s attention to the potential damage the virus can cause, as has been seen particularly in Europe and the United States. As Senegal eases the restrictions that were put in place during the early days of the pandemic, artists continue to support the national response. It remains to be seen whether the catalog of COVID-19 songs will continue to grow, and how the content of the songs will adapt, based on constantly evolving information about a novel virus and a global pandemic.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Professors Fallou Ngom (Boston University) and Tyler Fleming (University of Louisville) for their insightful feedback.

Appendix

We encourage the reader to listen to the playlist from Senegal concerning the COVID-19 pandemic: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLssDmLwEHQhfWlemjZoO1zJ6r71_JtRkL