Introduction

In a digitally networked age, to describe the relationship between the Nigerian state and history can mean to imagine how successive governments have routinely unfriended the past through educational policies that undermine the chronicling and pedagogic transmission of history in the country. How the Internet facilitates a practice of historical recovery or retweeting—to use another social media metaphor—is the goal of this article. Encounters with history in Nigeria are being shaped publicly by digital media that facilitate connections to the past as a mode of resisting anti-historicism, even as we highlight the problematic politics of the Net’s very design and structure.

Safiya Umoja Noble’s Algorithms of Oppression is one of several recent studies that crystalize the view of digital technologies as political entities which structure social meanings. That digital platforms and infrastructures are embedded in social and cultural meanings and are implicated in the circulations of forms of injustices and inequalities is at the heart of what she calls “technological redlining” (Reference Noble2018:1). As technologies of power, algorithms construct search engines as spaces that reinforce otherness and reify difference. Similarly, Ruha Benjamin has argued that technologies often hide, speed up, even deepen discrimination, while appearing to be more racially neutral than before (Reference Benjamin2019:7). In relation to other forms of domination, racism is not just an ideology or history, but rather a set of technologies that generate patterns of social relations that become Black-boxed as natural, inevitable, and automatic (Reference Benjamin2019:23). We start on this almost pessimistic note about the politics of digital technologies and platforms to stress an important point. Rather than presenting a romantic view of tecno-commercial infrastructures such as Google and Facebook that routinely monetize users’ data and endanger online privacy, our goal is to focus on the alternative cultural uses to which they are put.

On the one hand, we admit that digital platforms such as Google exercise “considerable discursive and hegemonic control over identity at the group and cultural levels,” and also have significant “control over personal identity and what can circulate in perpetuity, or be forgotten” (Noble Reference Noble2018:123). On the other hand, we deliberately go beyond this grim fact by foregrounding the historical voice of digital subjects who engage in conversations about the past in Africa-based virtual communities. We are using “voice” in Nick Couldry’s sense of the crucial process of submitting accounts of ourselves and the worlds we inhabit despite the forces of neoliberalism that structure modern communication (Reference Couldry2010:3). Voice matters and is evident in what Koleade Odutola calls “cyberframing” (Reference Odutola2012:17) to refer to how Nigerian intellectuals debate and discuss the variegated dynamics of nation-building on listservs that represent the digital space as a realm in which narratives are produced to shape Nigerian politics and culture. Mostly constituted by a combination of Nigeria-based middle-class scholars and an exilic class—which Farooq Kperogi refers to as Nigeria’s digital diaspora (Kperogi Reference Kperogi2020)—these online communities also signpost the imperative of class in Nigerian digital culture.

Based on the perspectives of Shola Adenekan and Helen Cousins (Reference Adenekan and Cousins2014), the question of class in African online discourses resembles that of digital access itself. In a country in which not everyone has Internet connections, educated netizens, mostly in the middle class, post content in online forums, and on blogs, and social media platforms as an expression of participatory politics and cultural engagement. The International Telecommunication Union, a United Nations agency, reported in 2018 that 3.9 billion people (51.2 percent of the world’s population) would be online by the end of that year, with the strongest growth seen in Africa (UN News 2018). However, even in 2021, a vast number of people in the global south still remain without access, despite such milestones. This can mean that a digital divide that produces “a new kind of digital subaltern” (Kent Reference Kent2008:84) also makes cultural and political interactions a class affair. Nigerian digital subalterns, citizens with no access to digital platforms, are not citizens in the same way as netizens are. References to “ordinary Nigerians” narrating history online may also presuppose another class of “digital subalterns” who, although they have Internet access, are marginal to, and excluded from, hegemonic power structures they resist on social media platforms. Any sense of history as coming from below is thus mediated by the vexing questions of class politics based on Internet access. A subaltern class with no access to either the Internet or hegemonic power structures is excluded in a manner that signals the limitations of the Net and the political underpinnings of its infrastructure and deigns. Whether it is through the epistemic violence of the protocols and algorithms of digital technologies or through the deployment of their authorial and functional structures for politicized speech, the digital realm is a site of political contestations that animate new publics. That said, the digital worlds we inhabit, despite their entanglements with power structures, also manifest different forms of cultural possibilities, including the enactment of historical subjectivities. That is the stake we pursue.

On Google Doodles

The politicization of the Google search engine may be typified by its doodles. In the over two decades since the global technology company started creating what are known as “doodles,” Google has produced thousands of custom search engine homepages for its domains around the world by making changes to the Google logo “to celebrate holidays, anniversaries, and the lives of famous artists, pioneers, and scientists” (Google, n.d). There are, however, political meanings attached to doodles, even as these visual narratives are both emblematic of Google’s presence in the country they celebrate and are performative expressions of their solidarity with nations whose historical legacies are visualized and broadcast through the significations of the doodle. With the 2014 winter Sochi games in Russia, Google produced a doodle that appeared to be a form of resistance against state-sponsored homophobia, as it presented athletic events as acts from which ideologies proceed. Pushing back against Russia’s anti-gay legislation and the country’s heteronormative conservatism, the Google doodle (see Figure 1) was designed with rainbow colors that symbolized and further normalized gay pride in Russia, accompanied by this statement from the Olympic Charter: “The practice of sport is a human right. Every individual must have the possibility of practicing sport, without discrimination of any kind and in the Olympic spirit, which requires mutual understanding with a spirit of friendship, solidarity and fair play” (Bennett Reference Bennett2014). Through this Google doodle, the search engine bar manifests as a spatial arena that connects digital technologies to power relations.

Figure 1. Google Doodle for the 2014 Winter Games in Sochi, Russia.

Similarly, in several African countries, Google doodles are produced and affiliated with major sporting events, the celebrations of national independence, historical personalities, or even national elections, constituting important visual texts of Africa’s recent postcolonial histories. These images, alongside several other popular memes on the Internet, bear witness to the present, while documenting and connecting it to the past. Since 2008, when Google produced doodles to mark South Africa’s and Morocco’s independence celebrations, the company has created images that recall other significant events on the continent, as well as celebrating the lives and achievements of several African leaders. Because of the ideological significations that doodles produce through different kinds of political and historical encounters with users of Google around the world, we examine the local iterations of this visual culture in the Nigerian digital ecology as one of the digital opportunities to learn history in the country. First, Google doodles are significant in the context of the powerful messages they circulate in a country that manifests a troubled relationship with its past. Also, the ways in which digital subjects in Nigeria themselves are directly involved in a process of historical recovery that is visible in the deployment of social media for historical transmission and re-education is key and will form the second half of our intervention.

For this second argument, we undertake a reading of photographic images which, although they are sometimes decontextualized from their original locations, histories, and purposes, are deployed by netizens to resist an elite culture of forgetfulness by the Nigerian ruling class. We focus on photographs on social media, centering posts and discussions from the Facebook group The Nigerian Nostalgia Project (1960–1980) to gesture at the archival possibilities of social media. The Facebook group is “a popular culture identity-focused organization” that “aggregates digital images, documents, sound bites, and video footage from a plurality of public and private sources” (Nigerian Nostalgia Project, “About This Group” n.d.). Since its creation on October 2, 2010, by Etim Eyo, one of its founders and current administrators, the group has used these materials to promote thoughtful self-examination and a reconnection to Nigeria’s foundational ideals (NNP, “Our Story” n.d.).Footnote 1 Our central task is to demonstrate the role of digital technologies in the reconstruction of history in Nigeria, connecting these to the workings of nostalgia in Nigerian digital culture. The process of learning history is enhanced by these technological opportunities for social media users in Nigeria, as these digital media spaces potentially enable pedagogic avenues for netizens to learn about the Nigerian past and celebrate iconic public figures. Although we begin with Google doodle to show the political underpinnings of the search engine, we will focus a large section of this article on how the Nigerian Nostalgia Project (NNP) can more easily facilitate the documenting and archiving of Nigerian history through a public engagement with history.Footnote 2 The NNP demonstrates how social media creates and disseminates historical narratives through the digital labors of members virtually engaged in the production of social and family histories online. The reason we emphasize the Facebook examples more is in line with previous work on Nigerian social media that focuses on the amplification of the activist voices of Nigerian netizens who, as it has been argued elsewhere, employ Internet memes and viral hashtags such as #BringBackOurGirls, and #NotTooYoungToVote to document the recent history of Nigeria as a symbolic mode of signalling affiliations of citizenship online (Yékú Reference Yékú, Adelakun and Falola2018:219).

As the images below demonstrate, the Google Nigeria homepage has featured doodles focusing on social activists and feminist voices such as Ransome Kuti, as well as those that highlight and commemorate the death of sporting heroes, writers, and even professionals such as Stella Adadevoh. Adedevoh was the Nigerian medical doctor who identified and contained Nigeria’s first Ebola patient, preventing a major outbreak but lost her life in the process. The first example is a 2018 posthumous celebration of Stella Adadevoh’s 62nd Birthday and was made at a time different people online were petitioning the Nigerian government to honor and recognize her effort that stopped the potentially pandemic spread of the Ebola virus in Lagos in 2014.Footnote 3 By memorializing her work, the Google doodle is also participating in pushing back against a state-based apathy and silence that misrecognize and undermine the historical significance of Stella Adadevoh’s expertise and heroic effort. Resisting governmental silence is important because silence, in recent years, has become a screaming metaphor for the political indifference of the state in Nigeria. The #BringBackOurGirls social media campaign, for instance, was partly activated by the silence of the Goodluck Jonathan government and the way it handled the abduction of the Chibok schoolgirls by Boko Haram in Northeast Nigeria. The historical repression of narratives such as those of the Nigerian civil war is another way the state employs silence, and it is for this reason that silence is read as a form of historical erasure that images such as the Adedevoh Doodle undercut. Like the Sochi games example, the Google doodles on Nigeria are visual signifiers of technology’s involvement in political struggles, as in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. A screengrab of Google Doodles of Nigerian women leaders, Stella Adadevoh and Funmilayo Ransome Kuti.

The visual rhetoric of these doodles is a significant aspect of their meanings and underlying assumptions. The Ransome Kuti Doodle, for instance, presents a complex narrative of a former winner of the Lenin Peace Prize, an alternative Nobel for leaders in anti-colonial-imperialism movements. Through its rhetoric and the choice of images, the doodle captures the historical facts of Ransome Kuti as a teacher, politician, and the first woman to drive a car in Nigeria. Also re-presented to us is her documented legacy as a pioneer women’s rights activist and social crusader against patriarchal violence and other forms of structural inequalities in Nigeria. Funmilayo Ransome Kuti’s legacy of advocacy and activism is something the designer of this doodle stresses when she states that she “needed to create an image that would make the observer want to learn more about her legacy” (Ejiata Reference Ejiata2019). There is the sense in this view that those who encounter and “read” this historical image can “learn more” about the legacies and memories it circulates. This cultivation of a historical consciousness by the Google doodle is significant, despite the possible ambivalence that may define Google’s involvement in reconstructing the past because of its overarching corporate interests. We discuss this below as we consider one final example.

With doodle representations of the lives, works, and achievements of Nigerian literary greats such as Chinua Achebe, Buchi Emecheta, and Olaudah Equiano (see Figure 3), Google produces a body of visual imageries that enable an appreciation of the rich history of literary imagination from Africa. In the discourse of African literature and the literatures of the African diaspora, Equiano’s position as a pioneering literary voice is well documented. Although his Nigerian birthplace is contested by Vincent Carretta (Reference Carretta2007), Equiano is generally seen as a Nigerian-born British binomial citizen and former slave who became a leader of the movement to abolish the slave trade in the 1780s. His autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, is an important canonical text of black literature. Olaudah’s Interesting Narrative contributed significantly to turning British public opinion against the slave trade, as he emerged as a critical voice on the subject of the transatlantic slave trade. His vivid recollection of his Nigerian childhood and his description of the experience of being captured and sold into slavery made him an important figure in the abolitionist circles in London. What Equiano’s Google Doodle accomplishes is not merely the celebration of his posthumous birthday but also a reiteration of the Nigerian’s significance in the context of actual historical events such as the transatlantic slave trade. The far-reaching consequences of these doodles are significant, especially in relation to the Equiano example and in terms of the circulation of ideas that cohere around his identity. Unlike many other Google Nigeria doodles that are seen only within the country, the Equiano doodle reached many other parts of the world, a fact that underscores his global fame. In addition to literary encounters with Equiano, therefore, many other people around the world, non-academics in particular, have an opportunity to learn about a major historical figure whose abolitionist work remains foregrounded in official historical documents and sources.

Figure 3. A Google Doodle for Olaudah Equiano’s 272nd birthday.

Although Google claims its major interest is to celebrate pioneers and achievers, its commitment to preserving and circulating history is apparent in these examples. What may be problematic, though, is how these doodles may also function simultaneously as capitalist appropriations of historical personalities and legacies from Africa and around the world. Equiano, for instance, is also the subject of a recent subsea cable project by Google to connect Africa with Europe as part of the company’s global subsea cable investment. According to Google, the cable, named “Equiano,” will begin in western Europe and run along the West Coast of Africa, between Portugal and South Africa, with branching units along the way that can be used to extend digital connectivity to additional African countries.Footnote 4 A potential problem that some commentators see in this project is how it may demonstrate technology’s complicity in the tragic insensitivity to the history of symbolic and corporeal violence that the Atlantic represents. As Kenyan writer Shailja Patel imagines, to name a subsea cable connecting Africa and Europe after an enslaved African who, unlike over two million of his African kinsmen, didn’t end up at the bottom of the Atlantic is unsettling and obscene. For her, it is a capitalist venture that obscures and erases the work of an anti-slavery African who devoted his life to fighting the imperialism and capitalism that turned Africans into property (Patel Reference Patel2019). While some may read the Google project as an opportunity to honor and recall Equiano’s passage across the Atlantic, the possessive and dispossessive logics of the colonial moment in Africa are restaged through a technological infrastructure that metaphorically returns Olaudah Equiano to the Atlantic he successfully crossed centuries ago. The paradox inherent in this example is that while other visual forms such as Google doodles may celebrate Equiano’s past, commercial projects such as the undersea cable undercut that celebratory gesture.

In The Tools of Empire, Daniel Headrick discusses the nineteenth-century tools of colonization and colonialism that facilitated Europe’s imperial conquest of different parts of the world. He describes colonizing inventions such as breech-loading rifles, steamships, quinine, and submarine cables as tools of Europe’s colonial expansion (Reference Headrick1981:3). Similarly, it might be said that Google’s Equiano’s project, as well as the various doodles they produce, are visual tools of a new global financial empire that exist to strengthen Google’s hegemony. In other words, we can read these doodles as constituting archives of visualizations that reinforce the neoliberal hold of Google on the user’s consciousness even as their investment in the past is intertwined with the huge commercial opportunities the digitization of African narratives make possible. We can read the possible manifestation of computer codes and algorithms in the shaping of the African past as a digital subjectivization that frames African historical experiences and personalities as subjects of neoliberal capital. How algorithmically driven platforms “are situated in intersectional sociohistorical contexts and embedded within social relations” (Noble Reference Noble2018:13) should motivate thinking about supposedly benign practices such as doodles. This contemplative posture enables us to appreciate how the construction of the identity of African history, framed and determined by foreign technologies that embody the ideologies of their owners, may result in digital exploitations of the past.

Despite the possible contradictions inherent in Google’s projects on historical documentation, the doodles are useful for signposting an ongoing explosion of digital images in the chronicling of African history. Whether doodles or historical photographs, these images push us to consider a visual turn in African historical scholarship, one particularly invigorated by digital technologies. Like Google, the social media company Facebook structures any expression of agency on its platforms, with its design options, interface, and structure shaping the articulation of any historical memory. Despite the fact of Facebook’s ownership of the space of the conversations on Nigerian history, that these discussions are taking place at all and that they are improving the learning of history is worthy of scholarly attention, although as already mentioned the history being reconstructed is subject to the workings of class, since many without access to the Internet are marginalized. We thus highlight the ways in which regular Nigerian netizens, whether at home or in the diaspora, participate in discussions of the country’s history on Facebook and examine how nostalgia figures in these conversations. Based on conversations around Google doodles on many online forums, Google doodles of Nigerian icons also stage nostalgic encounters both about a glorious past and about the futures imagined through artistic logos for citizens of different countries.

It is, however, the Facebook group (with its several Twitter and Facebook derivatives on Yoruba and Igbo histories) that embodies this element of nostalgia most coherently. Participation in the NNP as a mode of resisting official devaluation of historical memory by the Nigerian state allows us to assess how the platform stages a performative constitution of nostalgia that renders visible a past employed by members to reimagine the future differently. Through the appropriation of social media as a network space sponsoring the emergence of online peer-to-peer communities, the NNP embarks on the repossession, dissemination, and archiving of Nigerian history. By providing a digital hub where Nigerian Facebook users can recover and discover a sense of historicity, the NNP offers an invigorating platform from which netizens “piece together, through commentary and discussion, the fragmented history of our collective recent past” (NNP, “Our Story” n.d.). Since the NNP is a crowdsourced digital archive and social media project, collating and collecting historical images “depicting scenes and people from Nigeria between the mid-19th century and 1980,” the project furnishes us with a space to reflect on how the Nigerian past and future connect on social media. Also, it enables an interpretation of the NNP approach to historical redocumentation and preservation from an artistic perspective, locating nostalgia and memory as productive categories harnessed to appreciate an aspect of Nigeria’s postcolonial condition.

Friending the past on Facebook

According to the administrators of the Facebook group: The “1960 –1980” in the name (“The Nigerian Nostalgia 1960–1980 Project”) is not a literal representation of the decades covered by the photographs posted in this forum. Rather, it is a symbolic reference to the shared experiences and collective identity of the “Nigerian” during the era encompassing the formation of the nation and its subsequent independence. The scope for subject acceptability in NNP 60–80 is from the mid-1800s up until 1980 (NNP, “About This Group,” n.d.). Alan Liu’s astute volume on the sense of history in the digital age can help us to understand the significant emergence of Facebook in the chronicling of Nigerian history.Footnote 5 The sense of history on NNP’s social media platforms combines epistemological and socio-historical paradigms. At the epistemological level that centers the sensational and virtual, the apathy of the Nigerian state toward providing the necessary infrastructural and structural conditions for engagement with the historical past forcefully presents itself. In the socio-historical paradigm of the sense of history, on the other hand, history is happening socially through the interactions of nation, class, ethnicity, or/and generation. History in this mode also takes place through an attachment as “social bonds become distributed in time to affect sociality with memories of long ago and dreams of communities far in the future” (Liu Reference Liu2018:162). Without digital infrastructures built by the Nigerian state, however, projects of recovering the past are undertaken through U.S.-based private media companies that control and own the data produced through these projects. Infrastructure thus becomes emblematic of the politics of technology.

Also, a reliance on an American company is not unproblematic in the context of a Nigerian presence in a field such as the digital humanities.Footnote 6 Social media platforms may be hailed as democratizing on the grounds that they are free, yet they are only “free” to the extent that we overlook their ability to engage all of us in unpaid data-generating activities. As Kate Eichhorn writes, the communicative capitalism that structures social media captures value from things that were once intangible, including our nostalgia (Reference Eichhorn2019:134). Unlike our framing of nostalgia in productive and performative terms, Eichhorn signals attention to the problematic use of a technology that monetizes our online experiences, and this is critical. However, it appears that members of the NNP, like other Nigerians deploying social media as a space to refigure power, are more invested in the prospects of resisting historical erasure and befriending the past. While we believe using platforms such as Google and Facebook for historical archiving has neoliberal implications that shape alternative expressions of nostalgia on the NNP, we yet identify specific aspects of the nostalgic playing out through photographs that constitute a digital history of Nigeria.

Unlike the Google doodles, which are fictional, the images shared on this Facebook group are actual photographic narratives of the Nigerian past shared by members who are mostly Nigerians, along with several other non-Nigerians. Studies exploring the intersection of digital technologies and photographic practices include Erika Nimis’s Reference Nimis2014 essay that stresses the various ways in which contemporary African visual artists re-appropriate photographic archives to transmit African history. Nimis’s work is an exploration of “photo-archival artistic practices” (Reference Nimis2014:556) rather than an in-depth scrutiny of notions such as new media and its impact on audiences and photographic styles or appreciation, the reproduction of historical memory, and the transmission of personal memories and collective nostalgia. Rather than representing mainly artistic collections, the NNP provides an avenue for a public engagement with Nigerian social history by non-state actors. Hence, digital technologies and user-generated media are influencing the ways in which Nigerian netizens and those in its diaspora relate to historical knowledge, presenting de-territorialized avenues for the articulation and construction of local and national memories.

The idea of “Nigerian nostalgia” itself suggests that the Facebook group is invested in nostalgia as a national project which is collectively produced by its members. There is a performative dimension to the ways in which the historical photographs shared on the platform serve as performances displayed as a form of social autobiographical commentary on the Nigerian past. As historical writings reflect particular social and cultural contexts, digital platforms such as social media can provide for these everyday users a critical moment assuring that their perspectives are fleshed out by the redocumentation of history taking place online. Tim Hitchcock’s idea of “history from below” (Reference Hitchcock2004) as one that foregrounds the narratives and stories of marginalized groups is being played out in the Nigerian social media arena, even as members of the group participate in discussions that amplify their peer-to-peer reconstructions of history. The ways in which Web 2.0 centers and makes visible the media experiences and narratives of users potentially make it possible for digital subjects to be part of the virtual processes of salvaging a grim situation in which Nigeria’s history is either incomprehensively documented or exists precariously on the fringes of the standard education curriculum. The NNP offers a virtual space in which past, present, and futures are imagined on the Internet by Nigerians at home and in the diaspora. There is a process of collective remembering at work on Web 2.0 platforms that enable heterogeneous and different voices of the NNP to bring multiple perspectives to visual narratives of Nigerian history. The broad timespan allows for a more nuanced visual representation of Nigerian history by a community of Facebook users ranging from professional historians to academics and regular but educated citizens with access to the Internet who take an interest in history. From discussions on the platform, it is evident that these different members of the platform understand history to mean the Nigerian past, in particular the period from before political independence until the 1980s. Very importantly, the visual stories on the platform bring to focus the creative, even if sometimes contentious, uses of the past to discuss the present on the page. The NNP relies on the new media principle of connectivity to facilitate an assemblage of voices interested in historical visual narratives, reconnecting its Facebook members to the everyday socio-cultural and political aspects of the Nigerian past. The narratives of the past on the NNP stress not only official sections of Nigerian history but also the mundane and the everyday, with collective and individual protocols of remembering and archiving that do not necessarily bind its community to any romanticized notion of the past. Rather, these processes commit the NNP archival community to revisiting, rediscovering, and reliving the history that shapes contemporary Nigeria, even as they have to respond to divergent perspectives in the group.

Performative Nostalgias

The ways in which digital technologies and social networking sites such as Facebook re-politicize and reinvigorate Nigerian citizens, empowering them to mobilize online reconstructions of the past as a modality of recuperating historical awareness, is central to our approach to nostalgia. In the direct context of the NNP and its iterations of aspects of Nigerian social history, nostalgia may be explained as an agonizing longing for the past that proceeds from constantly returning to better images of the country in order to negotiate the precarity of its present. While it manifests differently for members in the group, nostalgia, as we conceive of it, is a digital performance by members in conversations around photographs that map the contours of a past place or home that is arguably irrecoverable materially. The expressions of nostalgia on the NNP are not necessarily homogenous, as there are individuals, both Nigerians and foreigners, who post family photographs which recall different aspect of childhood experiences. Generally, irrespective of what is posted on the platform, there appears to be a longing by most members for a Nigerian past that supposedly worked better than the present condition does today.

Nostalgia “is related to a way of living, imagining and sometimes exploiting or (re)inventing the past, present and future” (Niemeyer Reference Niemeyer2014:2). In other words, nostalgia is a performative means by which members of the NNP self-fashion themselves as people who possess historical knowledge. While the cinema historian Teresa Castro links the production of a kind of “counter-history,” or “alternative history” (as quoted in Nimis Reference Nimis2014), to the artist-historian, user-generated media invites us to reflect on the ways we think about how the citizen-historian uses photographs to propagate both personalized and collective versions of Nigerian history on the NNP. With digital media, nostalgia becomes an effective mode of reimagining and rethinking the past, in this case based on the narratives of multiple visual texts such as videos and photographs from both private and public collections. Despite the possibility of reading nostalgia as a kitsch version of the past, it can be a useful mechanism for imagining an alternative future from the images and recollections of the so-called “good old days.”

One of the important ideas the NNP archive can invite us to appreciate is the intersection of nostalgia and digital technologies. Signifying re/presentations such as the media harbor a certain presentness that makes us seek and locate the past in present mimetic reproductions of culture. With user-generated media, this longing becomes expressed individually as netizens produce mediatized culture that recaptures the past and reimagines the future. By highlighting the “lifestyle, achievements, values, thought processes, and standards that existed [among everyday people and prominent citizens] in Nigeria prior to 1980,” and contrasting them with present conditions, the Facebook group creates “an interactive and emotional experience for the group participants” (NNP, “About This Group” n.d.). These members can contribute to the project by submitting public and private photos or videos, or simply by joining in the conversations that these historical artifacts engender. Since the NNP exists “to reconnect the Nigerian psyche to the socio-cultural and political space before, during, and after the colonial project in the country,” as the group claims on its blog on Tumblr, its capacity to disseminate a visual history of Nigeria to its citizens at home and in the diaspora is one grounded in a positive vision of history. While the crowdsourcing of Nigerian history is made possible because of the media’s propensity for connection and sharing, what needs to be emphasized is the way in which the platform facilitates the preservation of history and knowledge that pushes back at the state-sponsored erasure of history and memory.

As a crowd-sourced reconstructive archive, the NNP, together with the photographs and videos shared by participants, represent a determination to resist the politics of forgetting that the Nigerian state appears bent on imposing on the public sphere. Even though the educational policy that expunged history from the schools has now been reversed, there is still a national attitude toward history and culture that remains to be challenged, the kind that the Stella Adedavoh Google doodle foregrounds. Although there are no explicit references to government policies in the group, members share and discuss photographic images with an alertness to the conditions of historical erasure foisted on them by the state. By refusing to engage with its own history and the legacies of the Nigerian past in recent years, the government presents an ambivalent position that rejects the unpacking of the history of colonialism, decolonization, the Nigerian-Biafra war, and many other struggles and politics of post-independence Nigeria. Nigerian history is, therefore, being rearticulated through a mediatized and social mediated perspective in which the sociality of Web 2.0 platforms is engaged by an eclectic mix of professional, academic, and amateur historians offering and sharing alternative narratives through the reconfiguration of past visual culture.

The reconstruction of history in the online community serves to buttress a nostalgic longing for the past that could potentially foster national bonding as well as a shared and collective identity among its members, even as they debate different aspects of the country’s invaluable past. This reference to history in nostalgic terms is informed by the group’s desire to mobilize nostalgia as a mode of reimagining the present and inspiring a present generation of netizens. Perhaps important here is the claim that nostalgia could be restorative or reflective, two different perspectives on nostalgia, whose difference “lies in their attitude towards history in the present: restorative nostalgics try to restore the past, as in national and nationalist revivals everywhere, turning history into tradition and myth and monument.” On the other hand, “reflective nostalgics realise the partial, fragmentary nature of history, and linger on ruins and loss.” (Walder Reference Walder2010:11). Neither of these approaches represents the goal of the NNP, which has a vision to reclaim and repossess the past through visual archives that, as the group’s Tumblr Page suggests, “show[s] Nigeria’s true beauty and richness in culture both in the past and at this very moment” (NNP, “About NNP” n.d.). As people engage with the Nigerian past on the NNP, they participate in a shared and collective reconstruction of historical memory that potentially refashions nostalgia as a productive sentiment—expressed in the narratives of netizens participating in the documentation of the past. Depending on the promptings of the individual photographs, the impulse to recapture the past by merely having it on display, which we call performative nostalgia, can be accompanied by the two other forms of nostalgia identified above. In this first example, there is a clear sense of an image posted to the forum to recall a key moment in Nigeria’s political history. The image transports members of the forum to the time of Nigeria’s independence, staging a version of nostalgia that is more reflective and performative for its members than restorative. In this sense, photographs on the NNP mark nostalgia as operating both as a record of the past and as an exhibit that becomes spectacle.

Here in Figure 4 is an important print artefact of Nigeria’s independence purchased by one of the members of the NNP in 1960 as a memento and guide and which relates to how the countless photos on the NNP serve as artistic expressions of a digitally enabled memorialization of the Nigerian narrative. By digitizing and posting the souvenir on Facebook, Adebayo Ladipo is invoking the power of social media to share marginalized stories and to highlight an important aspect of the history of Nigeria’s independence celebrations. It is the same impulse for which Google creates a doodle to celebrate the country’s independence. The dialogic nature of Facebook assures that while history itself is being shared, there is also sharing and discussion by commenters who provide important contexts and narratives to the moments captured in the images. This post inspired another NNP member, Oliver Stephan, who, like several other members of the NNP, is a non-Nigerian member of the forum, to reflect on the first time his parents traveled to Nigeria “to cover the independence preparations and celebrations for German TV in 1960.” The fact that other nationals can participate in the activities of the group underscores the ways in which histories and memories are connected at a transnational level that gestures at the social web’s global dimensions.

Figure 4. A souvenir of Nigeria’s first independence celebration in 1960.

While the potential reinscription of colonialist ideologies in this Facebook archive may be troubling for some, the visual images and narratives of the Nigerian past harvested from personal colonial archives by European subjects who contribute content to the NNP further enable an appreciation of the ways these individuals confront and recall the legacies of the colonial moment in Nigeria. From the contributions of the descendants of ex-colonial subjects and postcolonial Nigerian netizens, one can see how the colonial past in Nigeria is being re-narrated jointly through the archival information and online discussions of both, producing a discursive space in the visual memories of empire to connect with the varied sites of national nostalgia in the group. While one may argue that colonial nostalgia informs the sharing of these photos, it is more fitting to read the contributions and narratives of the non-Nigerian members of the group as a desire to archive the Nigerian past and relive their memories of the country in a digital community on Facebook. With social media as further evidence of global media flows, this connected history of the colonial and the postcolonial subject is important. In Figure 5, Diana Johnson’s post which depicts a 1958 wedding picture further underscores this connected history of empire that is replayed on the NNP.

Figure 5. A wedding photograph from a member’s private collection.

In this example, a personal narrative of a member of the online archive is a window to understanding the existence of inter-racial marriages in pre-Independence Nigeria. A mixed-race marriage in colonial Nigeria challenges notions of race as a fixed social construct that serves certain hegemonic interests, since it imagines possible sites of intimacies between the colonizer and colonized. We should note here the contested history of photography as an iconic site of signification in the framework of empire and colonial history in Africa. In his chapter in Images and Empires: Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa, Paul Landau writes of how photography positioned Europeans as observers of Africans, noting the manner in which the photographic image was a medium for colonialism’s representational encounter with Africa (Reference Landau and Kaspin2003:142). Many images shared on the NNP Facebook page offer the vestiges of this encounter, but often in apologetic ways that recognize the epistemological violence of photographic images by sharing mostly intimate images of family history. The paradox, however, is that even such private photographs make intimate connections both with recollections of the history and with personal memories of empire in Nigeria, even as they signify as archival records of the past.

Aside from re-documenting this particular event, Diana Johnson and the other people who post historical images on the NNP platform provide examples of the constitution of history through the voices of the transnational users of the community. Our understanding of this development is that personal photos such as Johnson’s challenge the normative assumption that social media is a chaotic venue for the performance of unreal identities. More importantly, the constitution of historical information is no longer in the exclusive domain of the professional historian, since the previously passive consumers of historical knowledge, as long as they have Internet access, are actively engaged in the process of recording and transmitting the past.

The productive approach to nostalgia in our work is necessary, because as “the negative sense of nostalgia prevails, there is a tendency to neglect the reciprocal relationship between audience and media in generating the conditions for making sense and meaning” (Pickering & Keightley Reference Pickering and Keightley2006:930), both of past and present realities. While nostalgia might, therefore, be “an ambivalent desire for the past,” we conceptualize its associations within the NNP context as constructive sentiments produced through online visual culture for imagining present and future realities. One possible antidote for the so-called “dictatorship of nostalgia” (Boym Reference Boym2007:17) and the cooptation of history and politics by nostalgic emotions might be to develop an understanding of nostalgia as “a poetic creation, an individual mechanism of survival, a countercultural practice” (Boym Reference Boym2007:17), which Kerwin Klein (Reference Klein2011) locates as a therapeutic response to the crises of historiography. Having neither restorative nor reflective sentiments as its chief aims, therefore, the NNP offers a sense of nostalgia that is mainly performative, one that is reinforced by the self-presentational and visual strategies of social media as a user-focused media form. To show the true beauty of the past in a documentary sense that invites citizens to linger on it is to stage nostalgia on the NNP as a representation of the past displayed through photographic narrations.

Our appropriation of nostalgia within the framework of the Nigerian Nostalgia Project is this positive formulation of nostalgia that is not reduced to “the concept of a unique regressive, embellished social phenomenon of popular culture, historical amnesia or the consumer world” (Niemeyer Reference Niemeyer2014:6). From this optimistic viewpoint, nostalgia in Nigerian social media can be a source of national bond and pride in a country consistently fractured by ethno-religious tensions and, in recent times, Jihadist terrorism and economic recession. Historical knowledge is not only being shared and stored by the NNP community, it is also being reshaped and renegotiated as a strategy for understanding the present from the past. As the Nigerian state has a counter-productive approach to documenting and engaging with the past, “a crisis of relevance” (Dibua Reference Dibua1997:118) actively promoted by the wielders of official power in Nigeria comes to mind. It enables us to focus on the ways in which participants on the NNP subvert and resist this ahistorical stance. As visuality is an integral feature of social media, visual culture is central to the reimagination of the past that takes place on the Facebook group. Hence, visual signs and codes work more as the main artistic expressions than mere textual or linguistic narrations of the past, even if linguistic commentaries are modalities of interactions on the platform. While our work is focused more on ways the NNP leads to the production of nostalgia, we also need to say that memory which, though often tangled and unstable (Sturken Reference Sturken1997), is relevant to understanding the past because the processes of remembering on the NNP are bound up with the various sites of contestations surrounding aspects of Nigerian history (e.g., military rule, the Nigeria-Biafra war—which is a major source of unending argument on the Facebook page). In relation to the turn to memory in historical discourse in the 1980s, Kerwin Lee Klein notes:

It is no accident that our sudden fascination with memory goes hand in hand with postmodern reckonings of history as the marching black boot and of historical consciousness as an oppressive fiction. Memory can come to the fore in an age of historiographic crisis precisely because it figures as a therapeutic alternative to historical discourse. (Klein Reference Klein2011:137)

The NNP nuances Klein’s explanation of the emergence and representation of memory in historical discourse, precisely because the online platform operates in the context of the crisis of historicism in Nigeria. While history “as an oppressive fiction” that promotes hegemonic culture may be absent in current negotiations of historical knowledge in the Nigerian context, what platforms such as the NNP repudiate is the absence of a sense of history in recent national memory, as well as the official relegation of history by the Nigerian state. Put differently, what Klein (Reference Klein2011) calls “a historiographic crisis” manifests in the Nigerian context as a de-historization forced on the modern citizen of the country by its agents of power.

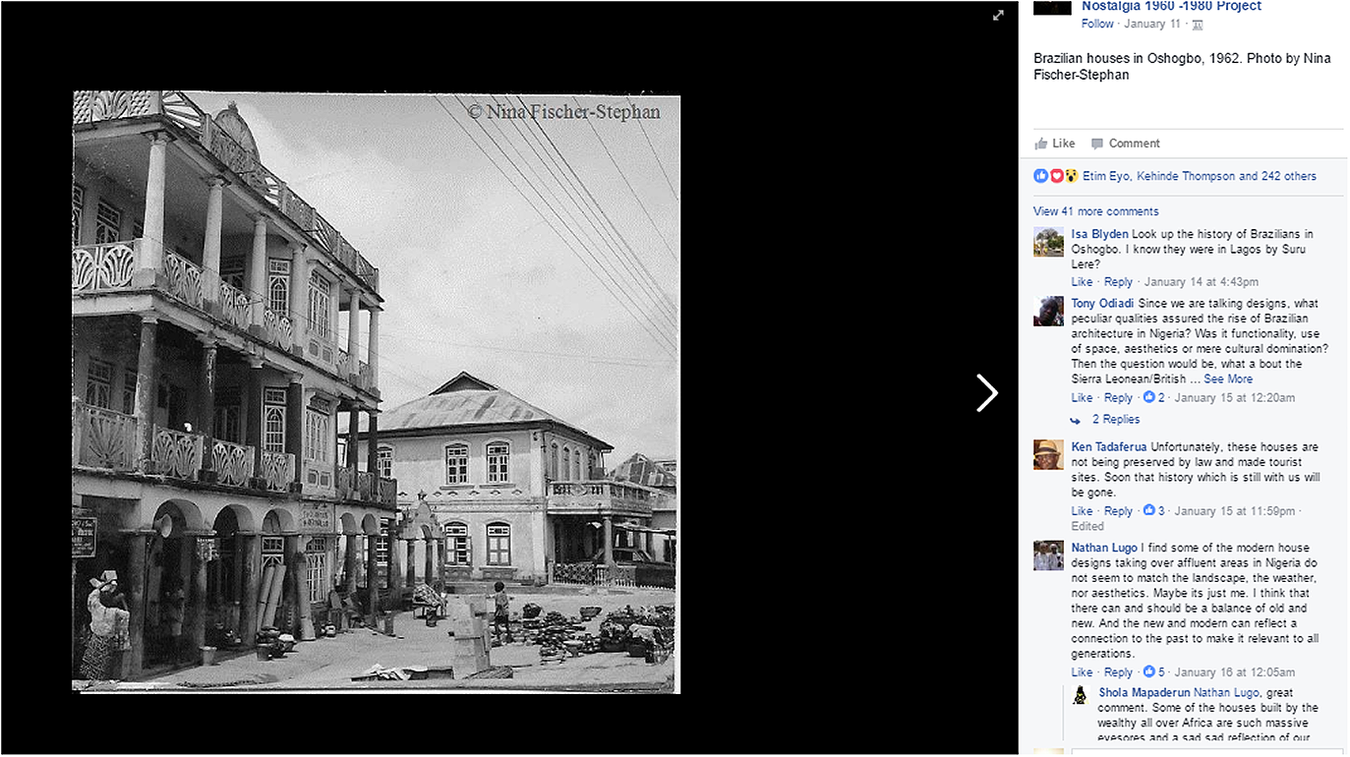

Considering the volatile nature of cultural and political conversations in Nigerian social media, one can appreciate the productive ways in which the NNP also serves as an epistemic site where Nigerian heterogeneous voices converge and negotiate the past in a mostly harmonious and decorous manner. Volatility is premised upon the argument that the Internet should be regarded as “a space of conflicting networks and networks of conflict so deep and fundamental that even to speak of consensus or convergence seems an act of naïveté at best, violence at worst” (Dean Reference Dean2003:106). Despite the possibility of conflicts in Nigerian social media, intensified by the precariousness of ethnic tensions, the NNP facilitates a discursive space in which the dialogic and interactive format of social media is used by its members to reconstruct Nigeria’s social and political histories, with members engaged in contentious but necessary debates on the Nigerian past. The photograph in Figure 6, for instance, depicts Brazilian architecture in Oshogbo, southwest Nigeria; it was taken by Nina Fischer-Stephan. Having provided commentary on another post, Oliver Stephan, in this example, provides one of the copies of the several photographs taken by his parents.

Figure 6. A photo of Brazilian architecture in southwest Nigeria.

Resistance Through Photography

As photographic texts, the various images submitted by members of the NNP serve to provide aesthetic avenues for expressing artistic sensibilities. As the founder of the NNP archive might have envisioned, the interventions are mobilized “to provoke or record thought or changes in the collective thought process by a variety of means that use art as a tool” (Personal communication with Etim Eyo, April 6, 2017). The NNP may not be composed of formal artists in this sense, but equally of interest to the group is an exploration of history through the use of historical photographs as a form of “speech,” in response to an institutional silence on history in Nigeria. This online speech is artistically harnessed as an online tactic of historical preservation on Facebook that resists the antipathy of the Nigerian state to historical subjectivity. This official attitude toward history underscores a gap, an absence in the national consciousness, since the state sees no connection between institutional locations of memory and power structures. In their seminal work on the making of memory and the politics of historical institutions such as museums, libraries, and archives, Richard Brown and Beth Davis-Brown write about “the power that is structured in and through the official knowledge discourse of the archive” (Reference Brown and Davis-Brown1998:21). Since to control the archive along with memory is to suppress alternative perspectives, the archive, as other scholars have shown, signifies as a cultural apparatus of domination. The repression of the archive, and of history, as is happening in Nigeria currently, is the state’s denial of historical memory.

The desire to archive the past though photographs submitted online by netizens is a practice that reframes historical discourse, redefining it as a private-public intervention owned and organized by netizens. In other words, social media facilitates a public understanding of the past through images and discursive commentaries of private citizens online. The view that there is a paranoid dimension of archival art that is rooted in utopia is another way to restate this poststructuralist anxiety about the archive: “The other side of its utopian ambition—its desire to turn belatedness into becomingness, to recoup failed visions in art, literature, philosophy, and everyday life into possible scenarios of alternative kinds of social relations, to transform the no-place of the archive into the no-place of a utopia” (Foster Reference Foster2004:20). To be clear, the rhizomatic spaces of online networks can indeed materialize both utopian and indeed dystopian versions of culture. Judging by the nature of historical discourses (for instance, on the Nigeria-Biafra war) produced on the NNP, the archive that emerges in online environments sometimes becomes a space of resistance to an institutionalized culture of apathy toward historical education, to the extent that citizens rendered ahistorical by the forces of the state encounter social media as a place for contending historical erasure. The members of the NNP come to it as place for recovering a sense of history displaced by the state with the help of one of its ideological state apparatuses, the school system.

The appreciation of these photos, as reflected in the comments on the thread of the post in Figure 6, invites the staging of heterogeneous voices that are in dialogue with various aspects of the Nigerian past, in this case the Afro-Brazilian heritage symbolized by the translation of Brazilian architecture in parts of Nigeria. These discussions on historical architecture are important conversations to have, as they resist the commodification and erasure of sites of memory in the country. Being able to participate in meaningful discussions on the past is not only a practice of reclaiming history through social media, it is also what marks the Nigerian Nostalgic Project out as a space for different Nigerians to learn and relearn history. While similar projects, such as Nsibidi Institute’s The Memory Project of Nigeria, merely invite people to document oral and visual history and send it to them, the NNP relies on the conversations and knowledges produced by members as part of the constitution of its identity and project. Footnote 7 The commentaries on the post become heteroglossic space in which individual comments take on lives of their own, as they become newer sources of historical knowledge that others can equally participate in. This view is certainly true of the comment of Bimbola Babarinde, who explains that one of “the earliest examples of Afro-Brazilian architecture in Nigeria was the iconic Olaiya House (built in 1855) near Tinubu Square in Lagos. Despite [being] declared a National Monument in 1956, it was demolished in December 2016 by some ignorant people.” Babarinde’s comment, while operating within the larger discursive framework of Stephan’s photograph, invites further reflections and arguments from other people, making the production of historical knowledge on the platform a decentered practice. Based on this example, the NNP makes visible the collective outrage of netizens who decry the commodification of invaluable objects and buildings that are carriers of valuable memories. Seen mainly through an economic optic that blurs the vital memory of their production, these objects become metaphoric of the vexation of the members of the NNP against a state that is indifferent to the past. These different historical perspectives people share offer trenchant criticism of the present state of historical documentation in Nigeria, while serving as virtual venues for members of the platform to participate in the reconstruction of national memory. The position of Ken Tadaferua on Stephan’s photograph articulates the point made earlier about the erasure of historical knowledge by the Nigeria state: “Unfortunately, these houses are not being preserved by law and made tourist sites. Soon that history which is still with us will be gone” (NNP Facebook). Social media thus becomes operationalized as a shared archival environment that responds to this possible and final disappearance of a sense of history in Nigeria.

The act of sharing gestures at an inherent functionality of Facebook that allows users to distribute data, as the “share” button marks an ontological character of user-generated media as a space for individualized circulations of culture. To share data is to mobilize a new media ritual expressing the ways in which networked platforms facilitate the transnational distribution of media and meaning along rhizomatic pathways. Features of social media such as interactivity, connectivity, and multimodality are thus used in the circulation of Nigerian history at a level in which the re/appropriation of photographic archives by the members in the group is staged as a collective practice enabled by digital media. There is the possibility that the sites of knowledges and meanings produced from the NNP Facebook forum could be readily discarded because of the nature of the medium as a non-scholarly space of communication. Such views, which delegitimize user-generated media content as chaotic and spontaneous productions unmediated by the establishment, foreclose the ways alternative constructions of history such as what obtains on the NNP might function to legitimize a vision of the past constructed by netizens. Rituals of connectivity and interactivity have epistemic consequences. In line with the view on the formulation of nostalgic emotions that “the fantasies of the past, determined by the needs of the present, have a direct impact on the realities of the future” (Boym Reference Boym2007:8), the NNP community appears to understand that the knowledges generated on the platform have consequences for Nigeria’s cultural image. Also, there is a generational perspective to the knowledge produced on the platform, since members of the NNP lived through the histories that are shared, while many others did not. This propels a space in which the historical conversations and knowledge produced connect the past and the present through the embodied presence of members whose lives intersect with the materials shared.

Finally, in the same manner as Google doodles memorialize the dead, another way digital memories and identities are expressed in this respectful environment can be found in the way that the platform is used as a site for the digital articulations of grief and mourning. The next example (Figure 7) is a 1966 photo of former Nigerian sportsman Paul Hamilton, who died on March 30, 2016:

Figure 7. A photograph of the late Paul Hamilton, a former Nigerian soccer player and coach.

Ed Keazor posted this image, rather than an obituary with a recent photo, onto the NNP as a way of remembering Hamilton and his past sporting activities for Nigeria. Since the medium enables a decentered approach to the sharing of knowledge and historical information, other users take the narratives of the photo in other directions, supplying more information on other athletic feats of the former Nigerian football coach. Other members are content with simply posting “RIP.” There is something about the way people mourn in the age of social media that is reflected in this post, namely the use of the social network pages of the departed as space for expressing solidarity and respect for the dead. As Rhonda McEwen and Kathleen Scheaffer make clear in their work on virtual mourning, “Facebook users mourn online to remember loved ones that have passed away, to connect with the deceased’s community of friends, to honor the life lived by the deceased, and to receive and give support to other Facebook users” (Reference McEwen and Scheaffer2013:2). In this particular instance, a prominent Nigerian is being mourned through an archival image that narrates his past. Unlike the typical virtual mourning on Facebook, in which users post on the timeline of the departed, what is evident here is the incorporation of historical memory in the process of remembrance. The Facebook user posts a historical artefact that reclaims history as a ritual of mourning and grief.

Conclusion

Technologies of history and culture manifest through digital platforms provided by Google and Facebook, two major internet companies invested in connecting peoples and histories. Despite the neoliberal ideologies that underpin these Net spaces, Google doodles and Facebook forums serve as vital and symbolic spaces that motivate a healthy nostalgia for the past. Despite the possibilities of data monetization, digital subjects in Africa are not mere consumers of digital modernity; they are actively and consciously invested in the repurposing of social media to document and reimagine the past. In comparison with external efforts such as Google doodles, the NNP is perhaps a more productive digital avenue, in which Nigerian netizens can reproduce historical subjectivities while keeping alive discussions on the Nigerian past. While a more nuanced and separate analysis of Google doodles could be undertaken in a future study, we have used them to demonstrate how technology overall is bound up with power structures. The doodles also connect to the importance of digital images in the transmission of historical knowledge, by signaling attention to how they make visible, along with photos from the NNP, a return to visuality in the narrative of the past. Although we have not discussed photos focused on politics, we note, as we conclude, that images harboring political discourses are, for understandable reasons, the most disseminated posts on the platforms. Because of the contested history of the Nigeria-Biafra war, for instance, historical references to first-republic leaders such as Awolowo, Azikiwe, and Balewa, or to previous military rulers, gain topical traction in these online discussions. The preservation of memory and the productive deployment of nostalgia as a site for connecting the past to the present are some of the major ideas that make “The Nigerian Nostalgia 1960–1980 Project” an engaging online resource for historical education and transmission.

The NNP archive stresses the role the emergent digital culture in Nigeria is playing to preserve the past in an age in which there is a crisis of historiographic education in the country. That our essay uses only four images out of the countless submissions on the platform is informed by the need to use representative images to begin a conversation on the use of these photographic texts on social media as a source of historical preservation. Besides, we wanted to accommodate images from the growing archive of Google doodles that are also beginning to feature prominently in various online processes of historical recovery online. We have chosen these particular images, which range from a personal wedding picture to photos of rare architectural monuments, to illustrate the diversity of information being discussed on the platform. Future Nigerian scholarship in history and media studies can benefit from a more sustained inquiry into the particular forms of discourses produced on the platform, the role of performance in relation to the staging of female bodies, as well as the other ways digital projects such as these may promote historical education in general. The next phase of the online archive, succinctly named NNP 2.0, hopes to serve as a digital space for synthesizing the audio-visual content gathered from different stakeholders on the current platform, even as the group’s administrators produce different forms of clothing members and others can wear to promote the platform. There are reasons to believe this new project will be based on a digital platform built and designed by professionals along with ordinary “historians” in charge of the various NNP social media sites. This will mean another worthwhile Africanist contribution to the digital humanities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the administrators of the NNP for permissions to use images submitted by members to the private group, Benjamin Lawrance and the editorial board of the ASR for their comments, and the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions and careful reading of the manuscript.