Introduction

Botswana held its 2019 general election amid a great deal of uncertainty regarding the outcome. Perhaps the 2014 general election served as a precursor, as it had featured an enhanced and well-resourced opposition campaign. The Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) entered the 2019 election having split for the second time in its history. This more recent split was led by former president Ian Khama, the revered son of founding president Seretse Khama. Following a political fallout with his successor, Mokgweetsi Masisi, Khama broke away from the BDP and offered his support to a new opposition party, the Botswana Patriotic Front (BPF). He also supported the opposition coalition, the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC), in a bid to unseat the BDP from power. As such, Khama capitalized on his traditional authority, leveraging it for political expediency.

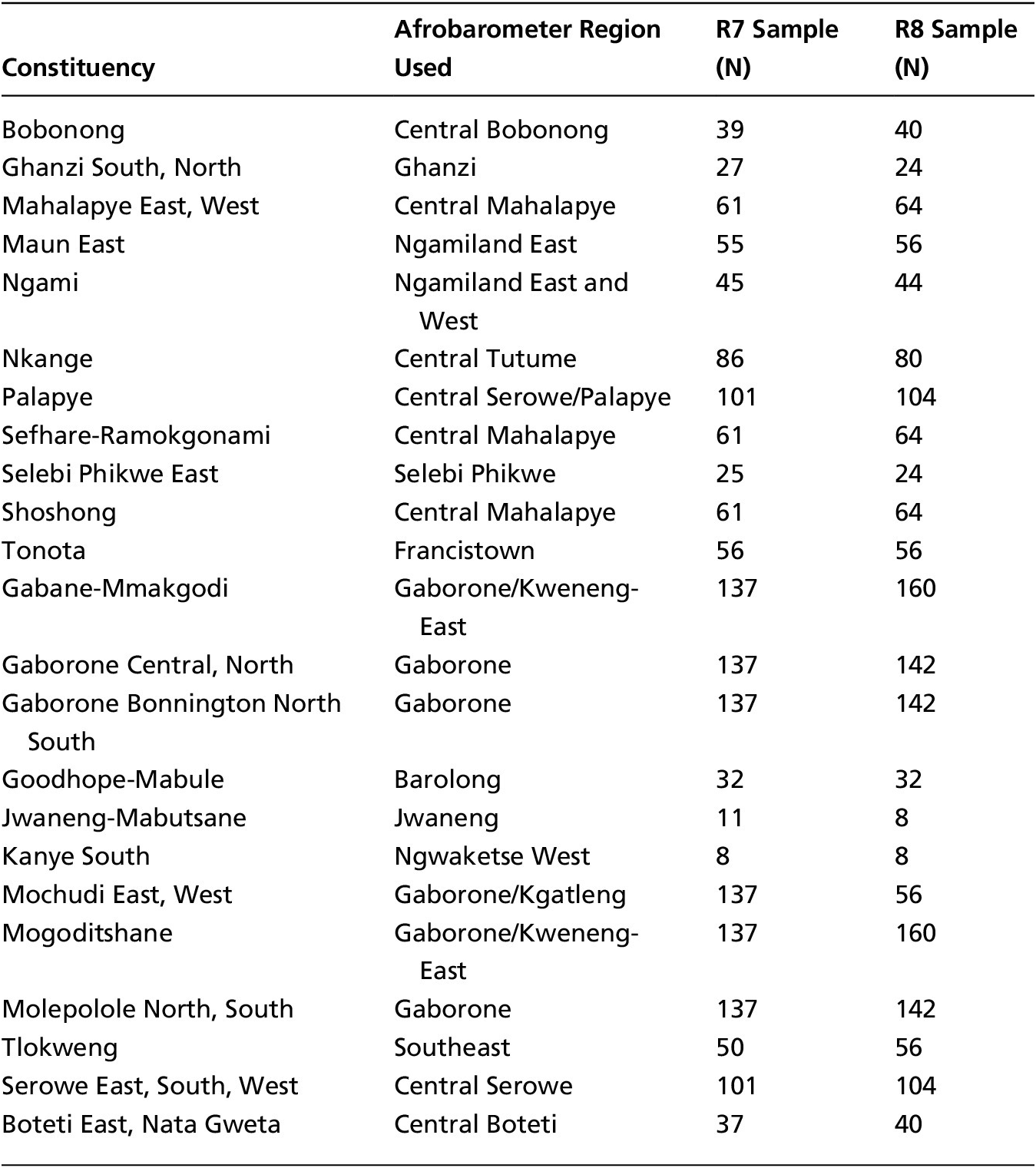

These elections were unique, in the sense that the UDC mounted a strong campaign against the ruling BDP, leading analysts and observers to predict a possible change of government. However, despite the opposition’s optimism in the runup to the election, the BDP was returned to power with a seemingly resounding victory. As shown in Table 1, on the surface, it maintained its two-thirds parliamentary majority (adding one seat) and won 53 percent of the national aggregate vote. On average, it won constituencies by a remarkable 24 percent, many by more than 30 percent. A shift in the balance of power may have occurred as the BDP made significant strides in the opposition’s historical strongholds. Scratching below the surface, the BDP also lost several seats in the Central District, its historical heartland. The overall outcome thus masks considerable fluctuation at the constituency level.

Table 1. 2019 Botswana Election Results

Source: Independent Electoral Commission of Botswana (IEC)

Note: Botswana has Single-Member electoral districts (SMDs) so the number of seats won is not directly or proportionally allocated.

This article analyzes the factors that shaped the outcome of the 2019 election. Using Afrobarometer survey data and official constituency results, we test relevant theories from the African voting literature, focusing on ethnic, partisan, and government evaluation explanations. Our central argument is that the 2019 general election served largely as a referendum on former president Khama, and by extension his successor Masisi, occasioned by Khama’s informal cooperation with the UDC. Khama’s connection to the Bangwato community, along with his campaign behavior, threatened to interject ethnicity into politics in a country long considered to be relatively immune from such influences. However, we find scant evidence that ethnicity played a major role in the contest. The BDP, which has been in power since independence, has been criticized by some scholars (Good & Taylor Reference Good, Taylor, Southall and Melber2006; Good Reference Good2010, Reference Good2017) as increasingly authoritarian. The internal struggle for its leadership, resulting in a severance with the Khama political family, has bolstered its democratic bona fides and led to a renewal of sorts.

Below we continue with a brief synopsis of Botswana’s electoral context, its political climate with commentary on electoral trends, and the rupture between Khama and Masisi. We then discuss voting theories to develop some testable hypotheses from the African literature and apply them to our specific case. Next, we discuss our methodology, followed by our analysis and discussion subsections, and we finish with some concluding remarks for the broader study of African elections and democracy.

Botswana’s Electoral Context

Since its independence from Britain in 1966, Botswana has held eleven successive elections, all dominated by the ruling BDP. Several explanations account for the BDP’s electoral supremacy. First, even though the elections have been judged to be free and fair (Sebudubudu & Botlhomilwe Reference Sebudubudu and Botlhomilwe2010; Cook & Sarkin Reference Cook and Sarkin2010), opposition parties decry the uneven political playing field (Molomo & Sebudubudu Reference Molomo and Sebudubudu2005; Osei-Hwedie & Sebudubudu Reference Sebudubudu and Osei-Hwedie2006; Sebudubudu & Osei-Hwedie Reference Sebudubudu and Osei-Hwedie2006). The ruling BDP has enjoyed incumbency privileges and used state resources to overwhelm opposition parties which have limited resources.

Second, opposition parties have also suffered incessant internal factionalism and fragmentation, which have diminished their capacity to challenge the BDP (Lotshwao Reference Lotshwao2011; Maundeni & Lotshwao Reference Maundeni and Lotshwao2012; Maundeni & Seabo, Reference Maundeni and Seabo2013; Poteete Reference Poteete2012). Third, successive BDP governments have been credited with prudent economic management, due to their investing diamond revenues in infrastructural development, education, and social welfare (Good & Taylor Reference Good, Taylor, Southall and Melber2006; Leith Reference Leith2005).

The fourth explanation is the BDP’s association with its founding leader and country’s first president, Sir Seretse Khama. Khama, a revered leader of his time, was heir to the royal chieftaincy of the Bangwato. Later exiled, he returned to become Botswana’s first president after the BDP’s triumph in the 1965 general election. Since then, the BDP has dominated constituencies in the Central District, a region inhabited by the Bangwato. This traditional status, later to be enjoyed and used for political capital by his son Ian Khama, as a de facto paramount chief of Bangwato, has sparked debates over the influence of chieftainship in Botswana politics. When he assumed power in 2008, not only did Ian Khama ride on the automatic succession politics of the BDP, but his traditional status also influenced the BDP’s decision to recruit him to stabilize and heal party factions (Good Reference Good2010; Nasha Reference Nasha2014).

From Khama to Masisi: A Bumpy Transition

Despite his popularity and charisma, Khama’s political legacy remains questionable, as the country’s democratic credentials were blighted during his tenure. The Directorate on Intelligence and Security Services (DISS), commissioned by Khama (Good Reference Good2017; Nasha Reference Nasha2014), was reportedly culpable for extrajudicial killings and harassment of opposition politicians. As a result, Freedom House downgraded Botswana’s freedom ratings, as some journalists were arrested while others fled the country (Freedom House 2016).

Unexpectedly, Botswana experienced an extremely turbulent power transition when Khama stepped down in April 2018 and was succeeded by Mokgweetsi Masisi. Almost immediately, Masisi moved to reverse a number of his predecessor’s policies. He instituted policies regulating the liquor trade, extending trading hours for businesses, and reversing the elephant hunting ban (Bloomberg 2019). The firing of Khama’s close ally and former intelligence service director Isaac Kgosi, and later his arrest, were probably the tip of the iceberg in Masisi’s attempt to consolidate power. The other school of thought on the feud suggests that Masisi did not honor a succession deal with Khama over the appointment of Khama’s younger brother as vice president (Kgalemang Reference Kgalemang2018). However, Khama would deny these allegations as a source of the feud, rather citing ill-treatment at the hands of Masisi’s government.

Masisi’s rise to political prominence had not been entirely smooth, as some in the BDP had opposed his selection as vice president. Signs of opposition to Masisi’s authority emerged early, as fellow cabinet colleagues began to cast aspersions on his leadership credentials (Gabathuse & Johannes Reference Gabathuse and Johannes2017). Without a political base of support even within his own party, it would not be far-fetched to conclude that Masisi could only consolidate power by addressing Batswana’s frustrations with the Khama regime. In so doing, Masisi curtailed some of Khama’s retirement benefits, including banning his long-time privilege of flying Botswana Defence Force aircraft. A state media blackout on Khama eliminated the extensive coverage he had previously enjoyed. Masisi also moved swiftly to contain Khama’s influence in the kgotla meetings he addressed and tried to limit favorable coverage of his philanthropic activities, which included popular soup kitchens (Ramatiti Reference Ramatiti2018). At the height of the tensions with Masisi, Khama perhaps hosted these events more frequently in order to curry political favor.

In retaliation to the Masisi government’s perceived onslaught against him, Khama allegedly sponsored a motion of no confidence against Masisi in parliament, with the intention of ousting Masisi from office before the general election (Mmeso Reference Mmeso2018). However, the motion was soundly defeated. When the attempted parliamentary coup failed, Khama publicly pledged support for former minister Venson Moitoi to challenge Masisi at a BDP elective congress. Traditionally, BDP presidents who succeed their predecessors through automatic succession go uncontested on the eve of elections and remain the chosen one to carry the party forward. After Moitoi announced her candidacy, Masisi dropped her from his cabinet, causing Moitoi to withdraw from the presidential race at the Kang elective congress. Subsequently, the BDP confirmed Masisi as its 2019 presidential candidate. Faced with no other options to maintain control, Khama defected from the BDP, joining the newly established BPF. In an effort to exert maximum influence in the election’s outcome, Khama also pledged support for the opposition coalition UDC, traversing the Central District endorsing its candidates.

The 2019 General Election: A Possibility of Regime Change and Hung Parliament

The election’s uncertain outcome resulted from several factors. First, the resurgent opposition coalition put together a competitive campaign, which led many observers to predict a regime change or a hung parliament. The UDC campaign, allegedly sponsored by South African business billionaire Zunaid Moti, allowed top officials to reach far-flung constituencies via private jets and helicopters.

Khama’s defection also factored heavily into a potential BDP loss. The Khama family and name have been the backbone of the BDP, especially in the Central District, since the party’s establishment in 1962 (Good Reference Good2010). Controlling nineteen of the fifty-seven contested constituencies, the Central District holds significant electoral importance. After his defection, Khama strategically exhorted his constituents in the Central District to endorse UDC candidates in regions where the BPF did not compete. The defection of Khama’s younger brother and former cabinet minister, Tshekedi, to the BPF further cemented the end of the family dynasty’s connection to the BDP.

A BDP victory, however, still remained a possibility. The party’s optimism largely emanated from the hope that Masisi inspired in the citizens and the belief that he ushered in a new and improved era of BDP rule. Indeed, as highlighted above, Masisi utilized the period before the election to carry out an effective campaign, while implementing some policies that endeared him to the voters. He presented a somewhat “new BDP” that was to be marked by consultation, embracing private media and the labor federation movement. This was by all accounts a departure from his predecessor’s political modus operandi. What, then, accounts for how the people of Batswana made their electoral decisions in 2019?

Theories of Voting

We draw on the extant voting behavior literature to develop some theoretical explanations for voter motivation. Central to our concern is Khama’s ability to play the ethnic card. We develop hypotheses that engage with and tailor ethnic explanations to our specific case, and then briefly consider alternative theories (partisanship and government evaluations) to account for micro-level electoral decisions.

Ethnic Voting

Early studies of African voting behavior identified the role of ethnic identity in Ghana (Gyimah-Boadi Reference Gyimah-Boadi2001; Lentz & Nugent Reference Lentz and Nugent2000; Nugent Reference Nugent2001), Kenya (Bratton & Kimenyi Reference Bratton and Kimenyi2008; Elischer Reference Elischer2008), South Africa (Ferree Reference Ferree2006), Zambia (Posner & Simon Reference Posner and Simon2002), and across Francophone Africa (Fridy Reference Fridy2007; Toungara Reference Toungara2001). Central to these studies was the fact that the foremost cleavage structures influencing politics emanated from ethnic considerations, and that ethnic groups would exhibit uniform electoral behavior in choosing “one of their own.”

When assessing the specific mechanism, some authors (Ferree Reference Ferree2006; Fridy Reference Fridy2007) argued that voters used race and ethnicity as cognitive heuristics when making electoral decisions. Pippa Norris and Robert Mattes (Reference Norris and Mattes2003) found some support for the belief that ethnicity—measured as both race (respondents who identified as Black African) and language (those who belonged to largest linguistic group)—strongly conditioned citizens’ voting behavior. However, later empirical studies question the validity of ethnic explanations. Evaluating cross-national survey evidence, researchers highlight other cleavage structures—income, education, geography, linguistics, and occupation—as the major political fault lines (Basedau et al. Reference Basedau, Erdmann, Lay and Stroh2011; Lindberg & Morrison Reference Lindberg and Morrison2008; McLaughlin Reference McLaughlin2007; Mozzafar et al. Reference Mozaffar, Scarritt and Galaich2003).

Given the dominance of ethnicity in the African voting behavior literature, we probe its possible influence in Botswana. Over the years, scholars have connected BDP support with the eight major Tswana ethnic groups, perhaps with the exception of Bangwaketsi, among whom the BNF was more popular (Wiseman Reference Wiseman1977; Makgala Reference Makgala2005).Footnote 1 Even though Botswana’s political process is not structured around ethnic politics, John Wiseman (Reference Wiseman and Potter1997) contended that ethnic diversity existed and played a political role: Seretse Khama’s traditional prestige was immense within the Bamangwato. As discussed above, the community’s respect for Ian Khama could potentially shape members’ propensity to sever their long-standing connections with the BDP. Khama campaigned vigorously on behalf of the BDP’s opponents, targeting areas in which his traditional legitimacy was strongest (such as Serowe in Central District). If the ethnic argument holds, we would expect the Bangwato to follow their co-ethnic and defect from the BDP, supporting either the UDC or BPF, when making electoral decisions. As such, we posit that:

Hypothesis 1a: citizens who self-identify as Mongwato will be less likely to vote for the BDP.

Moreover, scholars have noted some traces of perceived ethnic neglect or discrimination by the BDP. This was evidenced by the relocation and the dispossession of the Basarwa of their land by the government (Good Reference Good1999). In a different vein, Dominika Koter (Reference Koter2019) illustrates that, during Khama’s tenure, levels of national identification among the Bangwato significantly increased as they believed they had acquired greater political standing. Khama’s very public spat with and severance of ties to the BDP, followed by well-publicized investigations into Khama’s allies, might have convinced the community that they had lost their newfound enhanced position. This may have further led them to conclude that their ethnic group was now facing political discrimination. We posit:

Hypothesis 1b: citizens who perceive their ethnic group faces discrimination will be less likely to vote for the BDP.

Alternative explanations

We acknowledge that other factors also shaped Batswana voting behavior. As such, we list two other explanatory variables that we will control for: partisanship and evaluations of government performance.

In the African context, some authors highlight a strategic partisan motivation—voters try to align themselves with likely winners, in an attempt to reap the benefits of electoral victory. Other researchers (Bratton Reference Bratton1999; Kuenzi & Lambright Reference Kuenzi and Lambright2007; Posner Reference Posner2007) stress the mobilizing effect of political parties. While partisan attachments have been shown to be relatively stable over time (Lindberg & Morrison Reference Lindberg and Morrison2008; Young Reference Young2009), some countries have experienced declining party identification. Similar to Keith Weghorst and Staffan Lindberg (Reference Weghorst and Lindberg2013:720), we acknowledge that partisanship does not lead to an automatic transfer of votes; rather, partisans may also be swing voters, and the effects of partisanship should be empirically tested.

In our specific case, the internal disputes within the BDP came to the fore well before the election, resulting in Khama’s party defection and Venson Moitoi’s challenge of Masisi in April 2019. The losing faction at the Kang congress, commonly known as “New Jerusalem,” publicly endorsed UDC candidates during the campaign (Gabathuse Reference Gabathuse2019; Kanono Reference Kanono2019). As such, we would expect that traditional BDP supporters who may either be taking cues from Khama or from disillusioned BDP party leaders would be more likely to consider alternative, possibly opposition, candidates at the ballot box. Conversely, BDP supporters who are firmly supportive of Masisi would be more likely to continue to support the incumbent party. Our analysis should also center on non-partisan Batswana, an increasing segment of the electorate.

When evaluating the performance of their government, voters across the world consider economic conditions. The well-established economic voting thesis posits that voters will punish incumbents during times of hardship and they will reward them for success; voters have quite sophisticated and multifaceted economic outlooks. Some (Lewis-Beck & Stegmaier Reference Lewis‐Beck and Stegmaier2008) claim that economic concerns weigh even more heavily in voters’ minds in the developing world. In the African context, economic performance evaluations of the government feature prominently in electoral decision-making (Posner & Simon Reference Posner and Simon2002; Bratton et al Reference Bratton, Bhavnani and Chen2012). Additionally, one may expect in countries that have held many successful elections since independence (such as Botswana and Ghana) that the voting patterns of their citizens may more closely resemble those of voters in the developed world. As such, economic issues may not be the primary concern of voters. Other factors such as education, infrastructural development, and healthcare may also have some influence.

Methods & Data

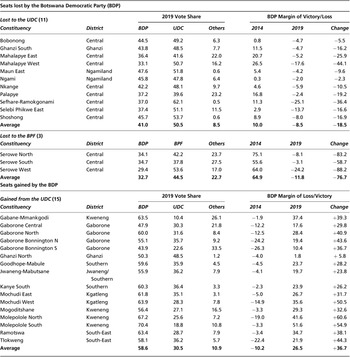

We make use of two types of analysis: first, we conduct statistical tests on available Afrobarometer survey data; second, we qualitatively assess the constituency-level data available from Botswana’s Independent Electoral Commission (IEC). A discussion about our data use is necessary, including transparency about the data’s limitations.

Ideally, we would have liked to have panel data that measured the change in Batswana voting intentions at different time intervals, corresponding to the political events detailed above. For instance, it would have been instructive to look at evaluations of both Khama and Masisi at different points of the electoral campaign. However, publicly available and credible survey data are limited in Botswana. As such, we have tried to maximize the inferential leverage afforded by the available survey data. The 2017 (Round 7) and 2019 (Round 8) Afrobarometer surveys conducted in Botswana are nationally representative, and both include 1,200 respondents. The 2017 sample was conducted in May; it captures the attitudes of citizens while Khama was still in office. The 2019 iteration was conducted in July and August, less than three months before the October 23 election. This fortuitous timing allowed us to avoid the temporal disconnect that plagues many electoral studies relying on Afrobarometer data (Lindberg Reference Lindberg2013:4). Utilizing both of these samples also allowed us to track the changes in Batswana attitudes before and after Khama left office, enabling some tentative conclusions on the broader political effects his departure from the BDP may have had on voting behavior.

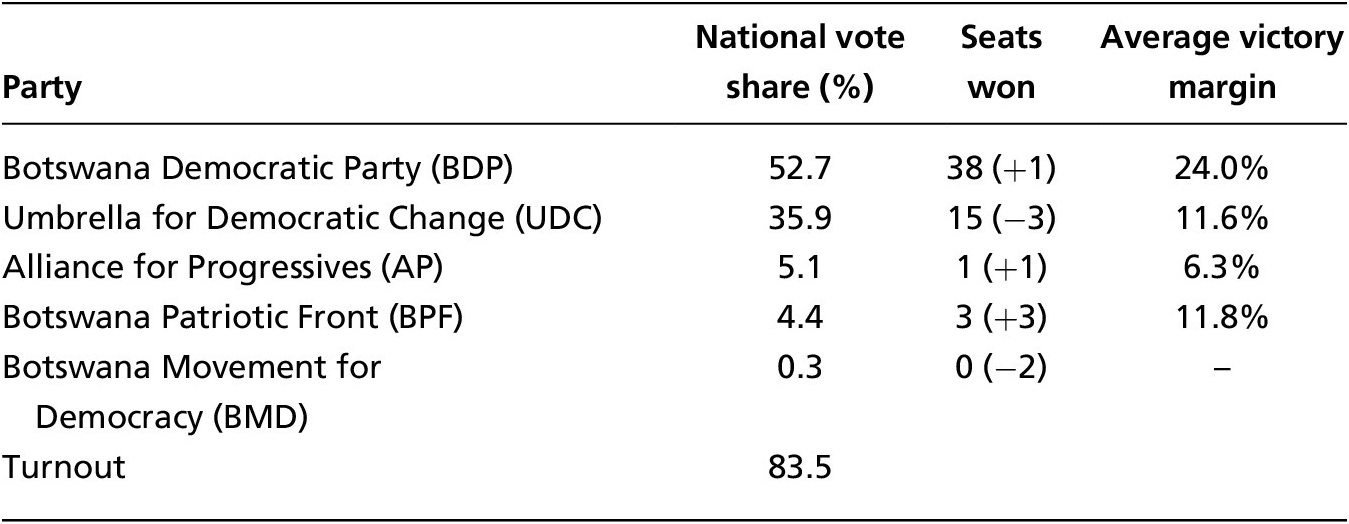

As with any use of survey data, there are questions of their representative nature. We compared the sample’s results with the results observed in the actual election. In Table 2, the first column illustrates that, in our sample, 81.4 percent of people reported that they would vote. This number compares very favorably with the actual results (83.5 percent). Similarly, the aggregated national vote measures in the election correspond very well with the figures from the sample (columns two and three). There is minor divergence in the vote shares for the BDP and other parties (overrepresented), and the BPF and UDC (underrepresented). There are some reasons that may account for this small discrepancy.

Table 2. 2019 Botswana Election Results

Sources: Afrobarometer Round 8 (2019) Botswana data, IEC

First, the constituencies are single-member districts, and many of the districts were not competitive. As the election approached, it is possible that some voters switched to the likely winner, as suggested by the decrease from other, smaller parties’ shares, or chose not to vote at all. Second, the BDP’s vote share decreased as both the UDC and BPF’s shares increased. It is unknown whether these voters shifted to these parties as a result of campaign appeals. However, in the context of our analysis and argument, we may be underestimating Khama’s campaigning effect, given that the survey occurred three months prior to the election. It appears that both the BPF and UDC improved their standing, albeit slightly, and some of this is likely due to Khama’s influence. One of the major political events occurred toward the end of the campaign, as Ian Khama’s brother, Tshekedi Khama, resigned from the BDP and joined his sibling in the BPF, contesting the election under their banner. This late disruption, a month before the election, sent the BDP scrambling to find a replacement candidate prior to the IEC’s deadline, but it also effectively secured Tshekedi’s Serowe West constituency seat for the BPF (Tau Reference Tau2019). In our analyses we also used questions that asked respondents to indicate their approval of incumbent president Mokgweetsi Masisi. Masisi assumed office in early April 2018 and had served in office for fifteen months prior to the survey’s data collection. Given his very public efforts to repeal and replace many of his predecessor’s policy initiatives, we assumed that respondents would be able to clearly assess his performance.

In line with previous empirical efforts (Basedau et al. Reference Basedau, Erdmann, Lay and Stroh2011), we employed a multistep analysis that utilized several statistical methods—bivariate descriptive statistics, logistic regression models—and then examined over time changes in presidential approval levels matched with constituency-level electoral outcomes. We started with descriptive statistics to probe the effects Khama’s departure from the BDP may have had on the ethnic components of party support, and whether his subsequent public campaign against Masisi had an effect on the attitudes among traditional BDP supporters.

We continued in our examination of Batswana voting behavior by using a logistic analysis that treated voter choice for the BDP as our dependent variable, modelling respondents’ support for the BDP in relation to all other party options (the UDC, AP, BPF, and BMD).Footnote 2 This analysis seemed particularly appropriate for the voting decisions of respondents, as one of our principal objectives was to examine the BDP’s support base relative to all other options on the electoral menu.

Our regression outputs featured in Figures 1 and 2 require some discussion. Similar to other empirical studies, we included standard controls for demographic characteristics—age, gender, education, and poverty.Footnote 3 Considering age, and given the BDP’s historical dominance and claim as the party of liberation, we expected that the party would still be able to rely on a reservoir of political capital among older Batswana. Gender was treated as a binary variable in the response, with female respondents serving as the reference group. Education ranged from zero to nine, with a higher score reflecting more years of education. Respondents’ location of residence included “rural,” “semi-urban,” and “urban,” with “rural” serving as the reference group. We had only a priori expectations for gender and geographic location. Michael Bratton et al. (Reference Bratton, Bhavnani and Chen2012) found that both female and rural residents were more likely to support the ruling party, while Amy Poteete (Reference Poteete2012) documented that the BDP’s traditional dominance of the countryside has continued, albeit weaker than in the early years after independence. In assessing respondents’ income and living conditions, we constructed an index of their material insecurity—how often they have gone without food, medical services, cash income, water access, and fuel. This practice has become quite common in studies of southern African voting behavior (de Kadt & Lieberman Reference de Kadt and Lieberman2017; Mattes Reference Mattes2015).Footnote 4

Figure 1. Marginal Effects Plot for Batswana Voting Intention for the BDP

Figure 2. Marginal Effects Plot for Non-Partisans’ Voting Intention for the BDP

Our three explanatory variables included measures of ethnicity, national government performance, and Khama’s and Masisi’s leadership. We made use of several questions to investigate whether ethnic identity shaped Batswana’s voting behavior. Similar to Bratton et al (Reference Bratton, Bhavnani and Chen2012), we tested whether the respondent’s ethnic identity relative to her national identity mattered, and whether she felt that her ethnic group had faced discrimination. Second, we considered each individual’s nominal ethnic identity. In doing so, we tested the argument that respondents who shared Khama’s ethnicity (Bangwato) would be less likely to support the incumbent BDP, relative to other ethnic groups and those who viewed themselves as Motswana only.Footnote 5 The government evaluation variable is an index of three separate questions measuring respondents’ assessments of the government’s performance with respect to creating jobs, fighting crime, and combatting corruption.Footnote 6 To test the argument that the elections served as a referendum, of sorts, on Khama, we included questions asking respondents about their approval of both Khama and Masisi.

Analysis and Discussion

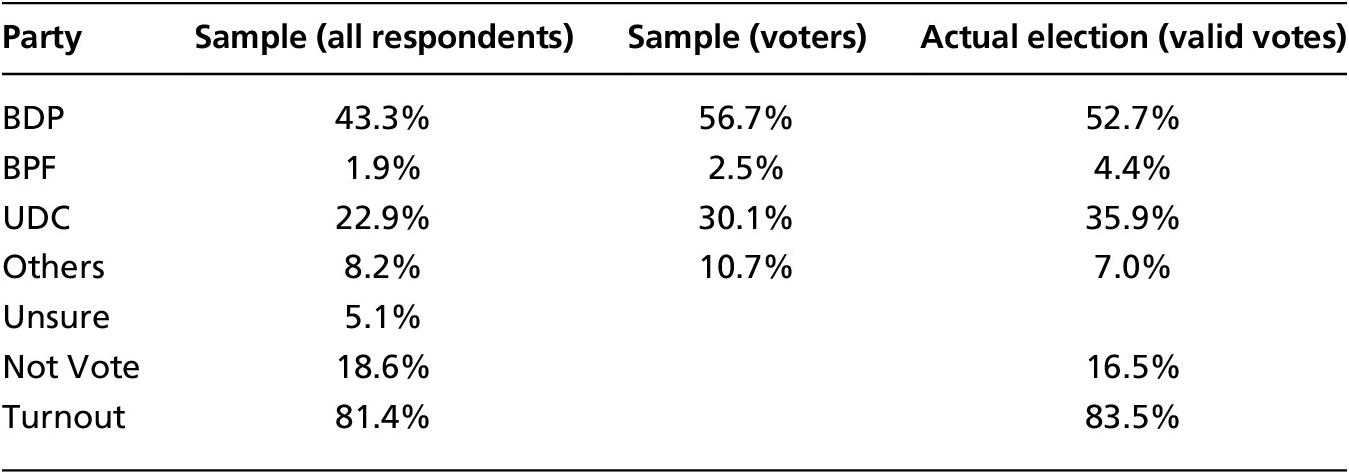

Table 3 illustrates the constituencies that were either gained or lost by the BDP in the election, to both the UDC and the BPF. The aggregate national election figures offer a misleading impression that the contest was marked by relative stability. At the subnational constituency level, the BDP lost fourteen seats while gaining fifteen seats. Our analysis aims to offer an explanation that accounts for both national and subnational results.

Table 3. 2019 Botswana Election Results, at the Constituency Level

Source: IEC

The BDP lost eleven seats in the Central District, two in Ngamiland in the northwest, and one in Ghanzi in the west. More striking than the electoral losses is the overall shift in voting patterns in these constituencies. In 2014, on average, the BDP won these seats by a comfortable double-digit margin (10 percent). In 2019, they averaged an 8.5 percent defeat, reflecting a swing of nearly one fifth of the district electorates. Even more troubling for the incumbent party is that only four of these seats were competitive (won by less than 5 percent) in the 2014 contest. Table 3 also demonstrates that the BDP lost all three seats to the Khama-backed BPF candidates in Khama’s hometown of Serowe, illustrating electoral sea changes in these constituencies. One preliminary conclusion that may be drawn from these figures is that Khama’s desertion, as expected, negatively impacted the BDP’s performance in the Central District.

Examining the other side of the same electoral coin, the BDP made significant electoral inroads in the southeastern part of the country, in or around the capital. In fourteen out of the fifteen seats it gained, the BDP reversed its fortunes from 2014 by more than 20 percent. On average, it won these seats by a remarkable 26.5 percent, illustrating an average shift of more than 35 percent across constituencies. Furthermore, the BDP won thirteen out of the fifteen seats with a majority of votes, a clear sign of electoral strength in the FPTP contests. What is perhaps most surprising is that the BDP had such an incredible electoral showing in an area over which the opposition has had a monopoly for decades. Specifically, the BNF had dominated the Southern District for five decades, while the opposition had claimed most districts in Gaborone for the past twenty-five years (Brown Reference Brown2020:707). The rest of the examination below further probes why the BDP lost seats in its historical stronghold (Central District) while establishing an electoral foothold in the opposition’s traditional bastion of support (southeastern Botswana).

Table 4 illustrates that party defection in voting was minimal for the two major parties, the BDP and UDC. However, when examining the Central District, it becomes apparent that partisan loyalty decreased slightly among the BDP, with the BPF gaining votes. For UDC partisans, roughly one in six of them selected others at the ballot box, with the BDP and BPF gaining a small number of followers. A central question at play in this election was whether BDP supporters in the Central District would show loyalty to the ruling party or abandon the incumbents, taking cues from their paramount chief (Brown Reference Brown2020). The lack of meaningful party defection among BDP loyalists suggests that these partisans decided to reject Khama’s appeals to support the UDC and BPF. Interestingly, UDC supporters may have abandoned their own party, mostly to support BPF candidates, while a small number chose the BDP. As such, another preliminary conclusion is that party loyalty among BDP partisans trumped Khama’s appeals to desert and defect to alternatives at the ballot box.

Table 4. Vote Choice by Party Affiliation

Sources: Afrobarometer Round 7 (2017) and Round 8 (2019) Botswana data.

In southeastern Botswana, the story was a little different. BDP partisans were still loyal, but slightly higher rates of voters defected than in the Central District and in the country as a whole. Again, UDC partisans remained very loyal, with few defecting to the BDP.Footnote 7 It is notable that independents again broke for the BDP, but to a lesser extent than in the rest of the country. However, the fact that the BDP won a majority of independents in this region speaks volumes to the ability of the BDP, and of Masisi in particular, to court voters. This is all the more important as this area had become an opposition stronghold over the past two decades. Independents, overall, broke consistently for the BDP, and of particular interest to this analysis, broke more heavily in favor of the BDP in the Central District. The inability of both the BPF and the UDC to make inroads with this vital sector of the electorate offers support for our contention that the underpinning factor of this electoral contest was a resounding rejection of Khama’s continued political influence. We proceed with explanatory efforts below to account for the rates of defection among BDP partisans and the voting motivations of those who lacked any affiliation. Together, these groups make up roughly three out of four Batswana in our survey samples.

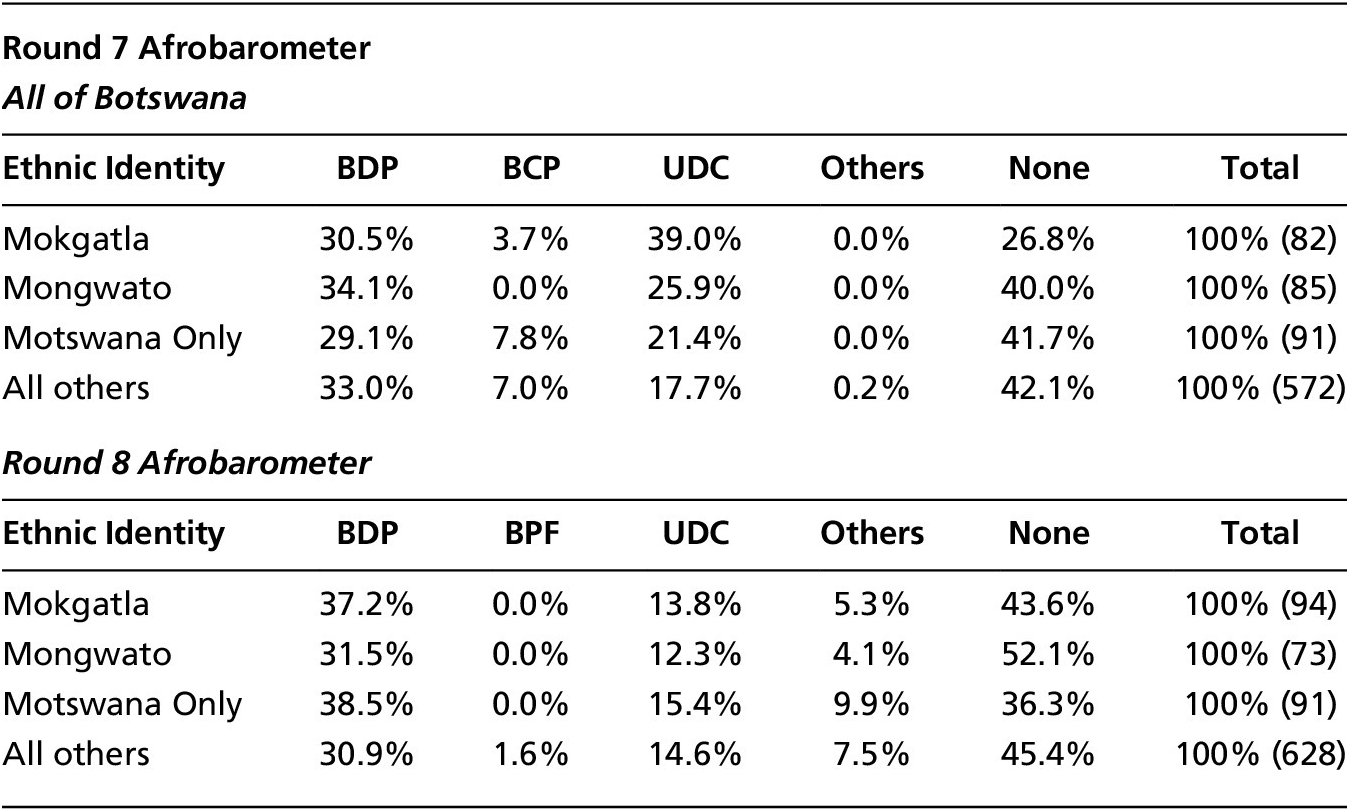

Table 5 illustrates that, considering the BDP and the UDC, some shifts occurred along ethnic lines. The survey respondents who self-identified as Mokgatla were more likely to claim an affiliation with the BDP over the two rounds, but more of them became politically unaffiliated. It is of particular note that support for the UDC dropped rather significantly between these two surveys.Footnote 8 These results offer some support for the ethnic argument, as Masisi himself identifies as a Mokgatla. Unfortunately, we do not have data that could show party-switching among respondents who identified as Mokgatla. As such, we tempered our findings. Behavior among Mongwato self-identifiers does cast doubt on the ethnic argument. We expected that this group, if they followed the cues from Khama, would switch allegiances to either the BPF or the UDC, at the expense of the BDP. There was a minor (2.6 percent) drop in BDP allegiance, but a major decrease (roughly half) in support for the UDC. Most damning for the ethnic argument is the fact that no Mongwato self-identifiers claimed BPF affiliation, undermining the expectation that the Bamangwato would choose ethnic loyalty over other political concerns. They did, however, claim greater political independence, and their ethnic loyalty may yet express itself in voting behavior, as analyzed below. Overall, the number of survey respondents who lacked a partisan affiliation continued to be a plurality in the sample. In Round 7, 42.7 percent claimed to be politically independent, increasing to 44.6 percent in Round 8. Thus, electoral outcomes in Botswana seem to partly hinge on the voting behavior of political independents, especially since there is a consistently high level of party loyalty at the ballot box. These observations guide and structure the specification of our statistical modelling below.

Table 5. Vote Choice by Ethnicity

Sources: Afrobarometer Round 7 (2017) and Round 8 (2019) Botswana data.

Figure 1 illustrates the findings of our logistic analysis, which accounts for the variance in why certain Batswana supported the incumbent BDP. We illustrate the marginal effects for each independent variable to adjudicate among their relative explanatory weight. Figure 1 confirms our earlier exploratory analysis that partisan attachment largely shaped voting behavior, with very little defection among party loyalists. What is interesting and key to our analysis is that political independents, even after controlling for sociodemographic and ethnic factors, were more likely to vote for the BDP; this warrants additional examination. Demographically, Batswana over the age of sixty-five are most likely to support the BDP, while urban and male voters are less likely to have voted for the BDP compared to their rural, female compatriots. While it was expected that Khama might pull away a noticeable number of his base, mainly the elderly, most older voters decided to remain with the party they had known and voted for all their lives.

When we examined only political independents, we found that older non-partisans were much more likely to support the BDP than their younger compatriots. Why these older citizens and other Batswana lack partisan attachment is beyond the scope of this analysis but warrants future study. Chief among motivations for independent voters was their evaluation of Masisi in office. This fact provides robust empirical support for our main argument that the 2019 election was largely a referendum on the Khama years and his continued political involvement.

Table 6 also illustrates the model run for survey respondents across political affiliation. What is striking about this analysis is that BDP partisans and political independents behaved rather similarly in making their electoral decisions in 2019. The factor that best explains their electoral decision-making is their approval of Masisi’s leadership, and we found no evidence that ethnicity shaped their preferences. Evaluations of Masisi mattered even more for independents than for BDP partisans, as illustrated by the positive and statistically significant interaction in column 3. The fractured nature of the BDP, given the divisiveness in the run-up to the election, could help account for this. Alternatively, Masisi as the face of the BDP seems to have offered a clear choice for political independents to reject Khama’s waning influence. In sum, we find clear and robust evidence that Batswana’s voting behavior was largely motivated by the voters’ evaluations of the incumbent president. We do, however, need to consider whether these evaluations mattered at the subnational level, to which we now turn.

Table 6. Model of Voting Intention for BDP in 2019 (logistic regression; baseline category is all other parties)

Note: + p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Source: Afrobarometer Round 8 (2019) Botswana data.

Constituency-level analysis

In Table 7, we supplemented our statistical modelling by considering constituency-level data available from Botswana’s IEC,Footnote 9 which allowed us to examine the relative popularity levels of both Khama and Masisi.Footnote 10 The figures illustrate the approval percentages for both Khama in Round 7 and Masisi in Round 8 Afrobarometer data. By this stage (July 2019), Khama had publicly called on his supporters to go out and vote for the UDC in districts in which the BPF did not field a candidate (Mail and Guardian 2019). As such, we demonstrate the gaps in votor approval between the two leaders and assess these differences within the context of actual electoral outcomes.Footnote 11 The constituency-level results lead us to three conclusions that lend support to our overall argument that this election was, in fact, a referendum on former president Ian Khama.

Table 7. Leaders’ Approval Ratings and 2019 Botswana Election Results, by Constituency

First, the BDP lost a total of eleven seats to the opposition UDC. In these electoral districts, Khama’s approval rating was significantly higher than Masisi’s, by an average difference of 30.7 percent.Footnote 12 Half of these defeated parliamentarians were incumbents, and, of note, several of them lost quite heavily (by double-digit margins). This is all the more surprising, given that, on average, the BDP won these districts by 10.2 percent in 2014; and that vote swings of 30 percent are exceptionally rare in Botswana (Poteete Reference Poteete2012:78). Given the massive swings in electoral fortunes for the BDP candidates, coupled with Khama’s popularity and Masisi’s much lower standing in these areas, it seems that Khama’s political shadow loomed large in these specific contests. It could well be that Khama’s clarion call to support the UDC candidates was heeded by his constituents.

Second, when considering the electoral districts the UDC lost to the BDP, again we examined the differing levels of approval for Khama and Masisi. Masisi was, on average, 10.7 percent more popular in these constituencies than Khama was in the earlier survey. The UDC won these districts, on average, by 10.3 percent in 2014, and twelve out of fifteen featured incumbent candidates running. Given the advantages of incumbency and the stark differences in popularity between Khama and Masisi, this time favoring Masisi, these results once again offer evidence for our argument.

Third, the constituencies that flipped from the BDP to the BPF once again fit the pattern one would expect if Khama’s popularity had shaped electoral outcomes. Given the location of these seats (Serowe, Khama’s home area), the observed effect should be even stronger. Again, the difference in Khama’s and Masisi’s popularity is vast—40.3 percent—and this lends support to the argument that voters in these regions were cognizant of the political animosity between the two antagonists and decided to support the BPF out of their loyalty to the former president. The Khama effect seems to be even more convincing when we consider that these three Serowe constituencies were won by BDP candidates by an average of 65 percent in the 2014 contests. The most direct impact Ian Khama had in these contests was to recruit his brother, Tshekedi, to desert the BDP and join him in the BPF. As a BPF candidate, Tshekedi Khama re-won the Serowe West constituency with 53.6 percent of the vote, almost double the votes of his nearest competitor.

In sum, the BDP picked up seats where Masisi was more popular than his predecessor, while the opposition UDC and BPF rode the wave of leftover Khama support to subnational electoral victory. Together with our above regression results, the collective evidence offers significant and robust support for our argument that the 2019 election actually served as a referendum on Khama, and, by extension, on his successor Masisi. In essence, voters made their electoral decisions pitting the long-serving icon versus his political and very personal rival.

One last remaining piece of our empirical puzzle is to consider which factors largely influenced the independents’ evaluations of Masisi. Above, we outlined the criticism lodged against Khama during his time in office—specifically, his autocratic tendencies and the perception that his administration was permeated by corruption. Considering these two factors, we ran linear regressions to model the independents’ evaluations of Masisi. Table 8 below illustrates that middle-aged independents who self-identified as either Mongwato or Mokgatla were much more positive in their assessments of Masisi. This again refutes the impression that ethnicity was a major factor in Botswana’s political system. Furthermore, independents who were more satisfied with the way democracy functioned in Botswana and less likely to perceive the president’s office to be corrupt were much more positive in their evaluations of Masisi. This offers support for the premise that voters cognizant of the worst abuses of the Khama years and convinced that Masisi offered a renewal for the BDP and the country in general gravitated toward the BDP at the ballot box. The interactions with both the Central and Southeast parts of the country yielded some conflicting results, likely due to the small sample sizes. However, they do seem to suggest that independents in the Central region were more concerned with the functioning of democracy, while those in the southeastern part of the country considered government performance in line with the president. None of the interactions achieved statistical significance, though.

Table 8. Model of Political Independents’ Evaluations of Masisi (linear regression)

Note: + p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Source: Afrobarometer Round 8 (2019) Botswana data.

Conclusion

As a model of democracy for the continent, Botswana has held twelve uninterrupted elections in its more than five decades of independence. As such, it is Africa’s oldest democracy. This level of consistent democratic political competition may have allowed voters to develop attitudes and behaviors resembling those of more economically advanced countries. Our findings allow for reflection on the broader African voting literature, as well as on the 2019 election’s consequences for the country’s democratic consolidation.

The defection of Khama from the BDP and his subsequent campaigning in his home region opened the possibility that ethnic appeals and mobilization could be interjected into Botswana’s political system. However, in this article we demonstrate that ethnicity does not seem to have played a major role in helping Batswana make their electoral decisions. Even where Khama played the ethnic card (the Central region), his co-ethnics, the Bangwato, were not less likely to express support for the BDP in any statistically significant fashion. In fact, consistent with our argument that the election was a referendum on Khama, and, consequently also on his successor, the Bangwato still largely identified with and supported the BDP at the ballot box. Furthermore, Batswana voters displayed rational behavior in assessing leader performance as well as the performance of the national government, corroborating earlier studies (Seabo & Molebatsi Reference Seabo and Kesaobaka2017) focused on the country, and on the voting behavior of Africans in general (Bratton & Kimenyi Reference Bratton and Kimenyi2008; Bratton et al. Reference Bratton, Bhavnani and Chen2012; Mattes Reference Mattes2015). As voters continue to base their electoral choices on leadership and performance issues, political parties are likely to become aware that they increasingly have to respond to governing shortcomings, thereby enriching the quality of representation. As others (Posner & Simon Reference Posner and Simon2002) have argued, voting behavior patterns more closely resemble those in institutionalized democracies after continued, uninterrupted democratic contests.

In much of the quality of democracy literature, Botswana is usually heralded as a success case and, relative to other African countries, rightfully so. However, some scholars (Good Reference Good2017; Makgala & Botlhomilwe Reference Makgala and Botlhomilwe2017; Mogalakwe & Nyamnjoh Reference Mogalakwe and Nyamnjoh2017) have recently questioned the country’s democratic health. Criticisms of the more than five decades of electoral dominance by the BDP usually center around the consequences of a perpetually weak and fragmented opposition competing in an unequal electoral playing field, non-competitive districts, and the creeping elements of authoritarianism in the country’s executive branch. The 2019 election, and the broader political conditions emanating from the outcome, offer a mostly but not entirely positive reflection. The country’s opposition parties launched well-funded and well-organized campaigns and defeated the BDP in over a dozen constituencies. However, the general lack of competitive districts, as demonstrated in Table 1, illustrates a reversal of the trend of increasingly close contests for most of the early twenty-first century (Poteete Reference Poteete2012); this represents a potentially worrisome symptom for the country’s democratic well-being.

More broadly, the 2019 election largely served as a fundamental rejection of Khama, his political allies, and his desire to continue wielding significant political influence. His tenure in office was plagued by an increase in governmental corruption, the persecution of political opponents, and malfeasance by close allies (Makgala & Botlhomilwe Reference Makgala and Botlhomilwe2017; Mogalakwe & Nyamnjoh Reference Mogalakwe and Nyamnjoh2017), leading some scholars to label Botswana a “highly elitist and authoritarian democracy” (Good Reference Good2017:114). In the last few years, Masisi has moved decisively to strengthen his own political legacy and to undo many of his predecessor’s policies and achievements. This has led him to, at times, directly challenge eminent political figures and Khama loyalists.

The political fallout of these decisions resulted in increased divisions within the BDP, which eventually culminated in Khama’s departure. The party’s internal turmoil spilled out into the public political arena, setting the electoral stage. In what seems to be a win for the country’s democracy, citizens adjudicated among the competing factions in the electoral marketplace. With nearly six out of seven eligible Batswana voters having their voices heard, they sent a strong signal to the troubled, former ruling guard. These outcomes seem to be positive for the internal party democracy of the BDP, as it has reformed itself after years of decline. The actions undertaken by Masisi to root out corruption and to ameliorate authoritarian tendencies in the executive branch largely resonated with Batswana, allowing for a more optimistic assessment of the country’s democratic trajectory and their emboldened leader. The removal and rejection of Khama from the political center stage offers hope for institutional renewal; however, it remains to be seen whether more widespread democratic improvements will be forthcoming.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Statistics Peer Group at the University of Botswana for inviting us to present an earlier manuscript in their seminar presentation. The authors would also like to thank the participants at the Workshop on Elections in Southern Africa in December 2019 at the University of Cape Town for their excellent feedback. A special thanks to Matthias Krönke, Joshua Gellers, Robert Mattes, and Russell Dalton for their insightful comments on early drafts of the manuscript. Finally, we would like to convey our sincere gratitude to the anonymous reviewers and editors of African Studies Review for their valuable feedback that significantly strengthened the article.

Appendix