“It is a calamity of biblical dimensions, but God doesn’t really come into it,” stated a 1974 article in the Atlantic Monthly, describing ongoing drought and famine in the Sahel. The remainder of the piece contains ghoulish accounts of the human suffering wrought by the drought, utilizing hackneyed imagery that has contributed to deeply problematic stereotypes about Africa and Africans that persist to this day. These tropes—so harmful in their longevity and consequences—encapsulate the horror with which not only European nations and the United States, but also China, the USSR, and Arab countries, viewed the drought crisis in the Sahel during the early 1970s.Footnote 1

Beginning in the late 1960s and accelerating in the 1970s, famine, as well as other contemporary crises such as the Biafran War, led to an unprecedented flow of foreign aid into West Africa, in the form of both food and capital. This contributed to the mushrooming non-governmental organization (NGO) industry (Rempel Reference Rempel2008). Indeed, the author of the Atlantic piece reported that she “met a number of foreign development experts travelling around the Sahel—you can scarcely turn around there nowadays without bumping into one.”Footnote 2 Legacies of this era, encapsulated in reporting such as the Atlantic article, have contributed to stereotypes of Africa as wreaked by poverty, dependent on outside assistance, and utterly desolate. Yet, the image of helpless Africans waiting on external succor belies the important and consequential initiatives that Sahelian nations undertook in the midst of this climatic catastrophe.

Scientific scholarship on the 1970s Sahelian drought has emphasized the long-term negative impact it has had on drought-affected populations’ livelihoods and health. Periodic droughts have affected the Sahel throughout the twentieth century, if not for longer, and have had major social, political, and economic consequences (Webb Reference Webb1995; Clark Reference Clark1995; Searing Reference Searing1993). The droughts that impacted the region during the late 1960s and early 1970s, however, were particularly devastating. While precipitation improved during the mid 1970s, drought returned in the 1980s. Longer-term trends show increased incidence of rain irregularities (Zeng Reference Zeng2003; Agnew & Chappell Reference Agnew and Chappell1999). Social science and humanities researchers also note the conjunction of environmental devastation, macroeconomic trends, and 1970s geopolitics, arguing that these hastened a re-subordination of African political and economic independence to “neo-colonial” forces. This culminated in structural adjustment and neoliberal policies in the 1980s (Dieng Reference Dieng1996; Lumumba-Kasongo Reference Lumumba-Kasongo2002; Fonchingong Reference Fonchingong2005; Kazah-Toure Reference Kazah-Toure2006). In particular, Gregory Mann has argued that drought contributed to undermining state sovereignty and led to the increasing importance of “nongovernmentality.” This served as a “wedge” that stymied state-building efforts, as NGOs gradually superseded state responsibilities and functions (Mann Reference Mann2014).

Yet, the environmental crisis in the Sahel also provided an opportunity for transnational action by African states in the Senegal River basin. This was remarkable because drought and reliance on external assistance simultaneously eroded the sovereignty of West African nations. Here, sovereignty means the capacity of national governments and state institutions to determine and enact economic, political, and developmental prerogatives. A long history contributed to the resiliency of transnational action in the Senegal basin. During the colonial era, government officials, engineers, and hydrologists had proposed the management of the Senegal River across political boundaries. The desire to develop the Senegal River as a single unit persisted after independence, as Mali, Mauritania, Senegal, and, for a time, Guinea, created a series of transnational river organizations to plan and implement river development programs. In 1972, Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal formed the Organisation pour la Mise en Valeur du Fleuve Sénégal (Senegal River Development Authority, or OMVS), which is still in existence.

The OMVS was emphatically a state organization, led by government officials and technocrats from Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal. However, it also surpassed the national scale in its purview and activities. OMVS officials ranged from ministerial-level politicos to state-employed experts in fields such as hydrology and agriculture. The heads of state of the member nations also directly participated in its affairs, particularly with regard to fundraising. The fact that the OMVS was a state entity but at the same time non-national is important and evinces the complex link between state capacity and state sovereignty. In a context of drought and famine, OMVS gave its member states the collaborative capacity to evaluate possible development schema, put forward proposals, and obtain funding. This resulted in enhanced sovereignty across the basin in terms of the ability to dictate the trajectory of development within and across borders, with planning occurring at a supra-national scale.

Further, the acquisition of funds by the OMVS during the 1970s and the successful implementation of a river basin-wide development program during the 1980s presents a puzzle at the heart of the relationship between state sovereignty and the international development hegemon that emerged during this period. If enhanced reliance on and imposition of externally determined developmental regimes and ideas was an increasingly prevalent form of neocolonial meddling, how was the OMVS able to largely avoid this trap and at the same time enhance its standing and autonomy? The OMVS was successful because it superseded limits of national-level action, becoming more than the sum of its parts through the coordination of efforts across the entire river basin.

This article utilizes various kinds of documents to present this argument: internal records, such as minutes of various OMVS meetings as well as resolutions, and planning documents, including impact analyses and policy statements. The OMVS itself produced most of the documents utilized during the first portion of this article. In contrast, the documents used in the digital analysis contain a substantial number authored by consultancies and firms under contract with the OMVS, although each section of the article relies on a mix of both of these general types. While differences between documents in each section of the article are not absolute and there is a degree of mixture throughout, these generalizations about content and audience are worth noting.

Using this evidentiary base, this article utilizes two related but discrete methods to demonstrate how the OMVS envisioned river development in response to the 1970s drought and how this enabled it to attract financing for its proposed long-term projects. It does so first through a close analysis of internal OMVS records, in particular meeting minutes of ministerial councils, along with their recommendations and resolutions. Then, the second part of the article employs digital text analysis to analyze a larger set of technical studies carried out and/or sponsored by the OMVS from before, during, and after the drought in order to show how the deployment of language by the OMVS related to food security and other development priorities, such as industrial development and navigation, changed.

Linking these two methods allows for an understanding of not only planning characteristics and why the OMVS sought financing for a basin-wide development program when it did, but also of how it was successful in attracting funding. In this manner, this article intervenes in two conversations, one historiographical, one methodological. The successful completion of major dam projects by the OMVS during the 1980s, after it had obtained financing during and following the 1970s drought, challenges the prevailing viewpoint on how this environmental crisis impacted West African political capacity. It shows the drought’s effects to be less uniformly negative than previously believed. Methodologically, combining a close reading of documents with digital methods has been enthusiastically adopted by scholars working in other disciplines and historical sub-fields, including United States history and literary studies (Spirling Reference Spirling2012; Wilkens Reference Wilkens2013; Blevins Reference Blevins2014; Grubert & Algee-Hewitt Reference Grubert and Algee-Hewitt2017), legal history (Funk & Mullen Reference Funk and Mullen2018; Guldi & Williams Reference Guldi and Williams2018), policy analysis (Laver & Garry Reference Laver and Garry2000), and diplomatic and international history (Hicks & Connelly Reference Hicks and Connelly2018; Allen et al. Reference Allenn.d.). Scholars of Africa have been slower to adopt digital text analysis, despite Africanists’ leadership in the use of digital methods for understanding the historical slave trade(s) (Eltis & Richardson Reference Eltis and Richardson2008; Domingues Reference Domingues2017; Lovejoy et al. Reference Lovejoy2019) and its suitability for research that focuses on institutions and organizations which generate massive source bases (Tiffert Reference Tiffert2019). This article provides an example of how Africanists interested in questions of development, post-independence governance, or the press, to give a few examples, might use digital methods to inform and answer research questions. It also constitutes a significant revision to understanding the limitations and possibilities of large-scale development planning and aid during the 1970s as well as to how Africanists might approach this topic combining digital with more traditional, non-digital methods.

The OMVS and Other Histories of Transnational Management

One key piece of the “puzzle” of how OMVS successfully proposed and implemented its river development program is that it rested on a deep historical and institutional infrastructure. Following World War I, French colonial officials and entrepreneurs began to carefully consider how the Senegal River basin might be profitably managed; this resulted in proposals to introduce intensive cotton agriculture similar to the Office du Niger’s projects in the Niger Valley in French Soudan (Sarraut Reference Sarraut1923; Bélime Reference Bélime1922, Reference Bélime1934; Conklin Reference Conklin1997; Bernard Reference Bernard1995). In March 1934, the Governor General of Afrique Occidentale Française (French West Africa, or AOF) formed a trans-colonial development unit, the Mission d’Études du Fleuve Sénégal (Senegal River Study Mission), which became the Mission d’Aménagement du Sénégal (Senegal Planning Mission, or MAS) in 1938.Footnote 3 The MAS commissioned numerous hydrological studies, conducted agronomic research at experimental crop stations, and pursued ethnographic research on agricultural practices.Footnote 4

Despite this long history, the Senegal River remains an overlooked site of coordinated transboundary activity. As Frederick Cooper shows in his 2014 monograph Citizenship Between Empire and Nation, becoming a nation state was not a foregone conclusion for French territories in AOF, as other political forms, particularly federations, held great appeal. However, the short duration—three months—of the only significant attempt at federation, the Mali Federation, has led scholars to conclude that there were no meaningful cases of non-national sovereignty in post-independence West Africa (Foltz Reference Foltz1965; Ndiaye Reference Ndiaye1980; Cooper Reference Cooper2014; Mann Reference Mann2014).

However, postcolonial riverine development organizations in the Senegal basin revise the narrative of the failure of non-national governance in Francophone West Africa. Since independence, there have been three transnational river organizations in the Senegal basin (Merzoug Reference Merzoug2005; Boinet Reference Boinet2013; Meublat & Ingles Reference Meublat, Ingles and Baré1997; Gautron Reference Gautron1967). In 1963, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal created the Comité Inter-États (Interstate Committee, or CIE) to coordinate the management of the Senegal River basin. Then, in March 1968, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal dissolved the CIE and founded the Organisation des États Riverains du Sénégal (Organization of Senegal River States, or OERS).

The OERS did not achieve its lofty ambitious. Seven months after its formation, a coup-de-état in Mali threw the OERS into turmoil. Later, on November 22, 1970, Portuguese soldiers, mercenaries, and Guineans hostile to Guinean head of state Sékou Touré launched an amphibious assault on the Guinean capital, Conakry, in an attempt to topple Touré’s government and assassinate the Portuguese Guinean anticolonial leader Amílcar Cabral (Arieff Reference Arieff2009). Touré immediately suspected that Senegal and its president, Léopold Sédar Senghor, had aided the Portuguese attack.Footnote 5 In March 1972, Guinea officially withdrew from the OERS. Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal responded by dissolving this organization and forming the OMVS.

While the Senegal Basin is an unusually rich site of transnational collaboration, there were a number of other African transboundary initiatives. Situating the OMVS in terms of IGOs, both in West Africa and elsewhere on the continent, provides critical points of comparison on how to grapple with and navigate regional integration in the face of environmental, political, and economic challenges. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) is one of the best known and most durable African IGOs. Founded in 1975 primarily as an economic and monetary union, its activities now extend to agriculture, industry, health and social programs, and military defense and peacekeeping (Fall Reference Fall1984; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2000; Camara Reference Camara2010). Outside of West Africa, the East African Community (EAC), the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) represent significant regional integration efforts, with the IGAD particularly comparable to 1970s Sahelian anti-drought efforts as Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Sudan, and Uganda formed the IGAD in 1986 to mitigate the effects of another series of catastrophic droughts (Weldesellassie Reference Weldesellassie2011). The 1980 SADC treaty posited that economic growth required regional integration. While disagreement between members and interference from external actors have at times stymied its activities, the SADC has had notable successes, in particular in developing a conceptual framework for the management of regional rivers (Chikowore Reference Chikowore2002; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Robinson and Thierfelder2003; Savenije & van der Zaag Reference Savenije and van der Zaag2000). The EAC is another important organization. It was founded by Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda in December 1967 but collapsed in 1977 when member states failed to approve a 1977–1978 budget, although it was revived in 2000. The initial focus of the EAC was financial coordination, but it also expanded into other domains, including education and aviation (Nye Reference Nye1963; Mugomba Reference Mugomba1978; Vaitsos Reference Vaitsos1978; Hazlewood Reference Hazlewood1979; Kasaija Reference Kasaija2004). While the SADC and EAC differ from the OMVS in emphasis, the three share ideological origins and the goal of regional solidarity. However, the OMVS differs in its narrower geographic purview and predominantly technical, developmental focus.

The Comité permanent inter-États de lutte contre la sécheresse au Sahel (Permanent Inter-State Committee to Fight the Drought in the Sahel, or CILSS) is worthy of particular attention because of its similarities to the OMVS with respect to goals, geography, and timing. Given the magnitude of the drought crisis, Francophone Sahelian nations, along with the Gambia and Cape Verde, formed a transnational community, the CILSS, to address the challenges of the drought and to attract and manage outside support. By the late 1970s, the CILSS had managed to secure around USD one billion, mostly in the form of loans and emergency aid. This is the transnational organization most associated with anti-drought action, despite the fact that its activities ultimately amounted to few durable legacies, in contrast to the OMVS, with its ongoing construction of dam projects in the Senegal basin.

Comparing the CILSS and the OMVS illustrates the constraints and possibilities that were encountered by IGOs in trying to obtain international aid. When Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal formed the OMVS in 1972, the Western Sahel deeply felt the effects of drought. The formation of the CILSS one year later reflected the situation’s gravity. While the OMVS did emphasize drought and famine relief, it also inherited a developmental agenda from the colonial-era activities well as the CIE and the OERS. Discussions within the OMVS administration illustrate the ways that political leaders, technical experts, and financial officers weighed which projects to pursue and, crucially, how to obtain financing.

As an intergovernmental organization, the OMVS occupied an ambiguous place. It maintained clear links to the governments of its member states but had discursive and political space to draw contrasts with its members. In particular, it could represent itself as a more responsible partner than its member nations through the creation of robust fiduciary practices designed to assuage donor concerns. Furthermore, the distance of the OMVS from any particular national government meant that its responsibilities did not lie with the politics or citizenry of any single member state, and like NGOs it articulated its language particularly to attract international donors rather than domestic stakeholders. At the same time, the OMVS shared some of the challenges that member states faced, particularly the requirement to solicit external loans to finance projects. Reliance on external funding could be a liability, and subordination to exogenous forces often weakened African state capacity for independent action, stymied the development of homegrown technical expertise, and ensnared nations in debt (Dieng Reference Dieng1996; Yansané Reference Yansané1996; Diop Reference Diop2016). Nonetheless, the OMVS’s identity as a transnational river development authority gave it flexibility in articulating how it could address urgent river development needs, allowing it to grow during a strained period for national governments.

The founding charter and institutional structure of the OMVS underscores this point. The OMVS was both connected to and separate from the nations making up its membership. Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal formed the OMVS on March 11, 1972, when they signed a convention creating the organization and laying out the basic principles of transnational river governance. Their objective was “to develop a close cooperation to enable the rational use of Senegal River resources.” This transnational model of development required that any project that might significantly modify the river needed the approval of all three member states for implementation.Footnote 6 The OMVS also claimed privileges that superseded the authority of the individual nations. A March 1976 framework agreement articulated these rights, which included exemptions from certain sovereign powers of the member nations. For example, “[the OMVS’s] premises [were] inviolable” and “agents and functionaries of the government of the host country, be they administrators, judicial officials, military, or police, cannot enter the headquarters to exercise their official functions” without OMVS approval.Footnote 7 Other special rights included protection of OMVS publications and communications from censorship, special identification cards and exemption from taxes for OMVS employees, and exemptions from import duties.Footnote 8 These regulations placed the OMVS beyond the reach of the member nation in certain domains, empowering it to operate with less national-level interference.

In April 1973, a little more than one year after the formation of the OMVS, the heads of state of Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal reconvened for the Second Conference of Heads of State and Government. At this meeting, their first since March 1972, drought was a major topic of discussion. The meeting minutes reported that “the Conference [of Heads of State and Government], preoccupied by the serious drought striking Member States’ lands, approved the decision of the Council of Ministers to engage, through the OMVS, a regional program to fight against the drought and desertification using the best possible paths and means.”Footnote 9 This required funding, so the Conference of Heads of State and Government decided that “in order to achieve this mission the Organization [OMVS] may receive donations, take out loans, and make calls for technical assistance with the agreement of the Council of Ministers.”Footnote 10

Managing to “receive donations” and to be in a position to “take out loans” was very important for the OMVS, since it could not count on substantial financial support from its capital-poor member nations; as late as 1977 the OMVS stated “financial constraints are certainly the most pressing.”Footnote 11 Meetings during the early years of the OMVS focused on how the organization could present itself to potential donors as a fiscally responsible partner. It needed to demonstrate that it would make efficient use of any funds it received, and in order to not be trapped by debt, to “negotiate financing under the most favorable terms.”Footnote 12 OMVS strategies for obtaining funds included creating a “Consultative Committee” in 1976 whose sole purpose was “to assist the High Commission and the OMVS in finding ways to achieve the Organizations’ program” by bringing together OMVS delegates with representatives from donor nations and international organizations.Footnote 13 The OMVS also structured itself in such a way that it would elicit the confidence of potential donors. In particular, it created robust internal financial regulations. The OMVS limited opportunities for misappropriating funds by requiring all deposits to be accounted for on the same day as their transfer; it forbade officials from making high-value contracts without written approval and created a position of financial officer with access to all accounts and the ability to conduct audits at any time.Footnote 14

Such tactics were necessary to make the OMVS an attractive destination for international financing. The CILSS employed similar strategies to attract funding. A 1974 CILSS internal communique outlined rules for making contracts and reporting expenditures, such as a regulation to “[pay] bills only by bank check,” and limited cash advances to CFA50,000.Footnote 15 In March 1974, the CILSS held a conference in Bamako for potential donors. Several speeches emphasized that the CILSS understood the potential concerns of donors regarding fiscal accountability. In his opening address, the head of the CILSS trumpeted its new “accounting division.”Footnote 16 The stakes of presenting a responsible image were high, as the Minister of Rural Development from Senegal told attendees that the CILSS needed “long-term credit, at very low interest rates, with deferments as far off as possible.”Footnote 17 Like the OMVS, the CILSS was preoccupied with attracting financial support, constrained by the economic weaknesses of its member states.

The fact that both the OMVS and CILSS were concerned with proving that they were trustworthy destinations for financial support during the Sahelian drought says something important about such West African regional organizations during the 1970s. Not unlike African nations in an emerging neocolonial order, they were reliant on donors and had to cater to their whims, prejudices, and preferences. One factor was the malign belief that African governments and officials were corrupt, which robust accounting practices purportedly mitigated. But, while both the OMVS and CILSS tried to attract funding by demonstrating fiscal responsibility, and both received substantial external support, the CILSS accomplished less over the long term. In contrast, the OMVS leveraged funds for a dual-dam project on the Senegal River. This is because the OMVS was able to pitch a precise river basin infrastructure plan to funders deeply concerned about drought and famine. It struck the right scale for potential donors, inspiring confidence in a concrete and apparently achievable program. The next section discusses how the OMVS deftly pitched its plan in terms of the overriding concern of the donors: food security.

The Two-Dam Senegal River Basin Plan

The specific river management program that the OMVS proposed involved two dams: the Diama Dam, near the mouth of the Senegal River about twenty-five kilometers upstream from Saint Louis, Senegal, and the Manantali Dam, in western Mali on the Bafing River, a major tributary of the Senegal (see Figure 1). Variants of an integrated Senegal River basin development program had been discussed since the late 1940s.Footnote 18 While the French administration paid for a series of studies for this project in the early 1950s, these did not result in any construction.Footnote 19 After independence, the CIE and OERS conducted their own studies, including a 1964 United Nations study that ultimately settled on Manantali as the optimal site for a hydroelectric dam that would also regulate river flow volumes while balancing downstream irrigation needs for Mali, Mauritania, and Senegal.Footnote 20

Figure 1. Senegal River basin with the approximate locations of Diama and Manantali Dams.

In the early 1970s, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) funded a second set of studies for the OERS. These studies were published in 1974, at an opportune time for the OMVS; the organization had a precise and detailed integrated river development plan in hand just as it began to search for financial backers. These studies represented the major vetting of an integrated program combining an anti-saltwater dam (Diama) with an upper-basin hydroelectric and regulatory dam (Manantali).Footnote 21 The plan emphasized that the Senegal River was a single unit that needed to be managed as such: “This program constitutes a homogenous set: it is the construction of Manantali and Diama Dams that will make the exploitation of available resources as well as navigation possible.”Footnote 22

While the OMVS had gotten off to a slow start after its formation, a turning point came in July 1974, when the OMVS hosted a meeting with potential donors in Nouakchott, Mauritania. This conference brought together significant amounts of capital and “demonstrated the interest and support that the international community had toward a frontal attack on the Sahelian problem.”Footnote 23 At this meeting, the OMVS presented a report synthesizing the findings of the UNDP studies. This document, according to a 1976 OMVS program report, “represented the affirmation that the development of the entire Senegal River Basin needed to be considered a common enterprise of the three states.”Footnote 24 The four main objectives of this “common enterprise” were to stabilize and increase the income of people living in the Senegal River basin, to reach a better equilibrium between humans and the environment in the Sahel, to reduce vulnerability to climatic factors affecting OMVS states, and to accelerate economic development through cooperation.Footnote 25 By 1976, the regional infrastructure program had obtained funding commitments from France, the Federal Republic of Germany, and Canada, and final negotiations were underway for support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).Footnote 26

Catastrophic famine, coupled with a fear of future recurrences, motivated the funding that enabled the OMVS to begin the Senegal River infrastructure program that centered around the Manantali and Diama Dams.Footnote 27 The 1976 program report noted that irregular precipitation, both across seasons and space, characterized the Senegal River basin. A lack of agricultural, industrial, and navigational infrastructure choked economic development, and “the situation is such that living conditions of the rural population remain precarious and worsen year by year. The result: rural exodus.” The report continued, “For the economic development of the OMVS states, the development of the Senegal River is a compelling need,” particularly in light of the drought, which was likely worsened by “the absence of regulating management systems.”Footnote 28 Indeed, “the solution to the Sahelian problem must be sought in the medium or long term.”Footnote 29 The integrated Senegal development plan was exactly the kind of medium- to long-term solution that could mitigate the impacts of future droughts; this was a project that was compelling enough to attract financial support.

In June 1976, the Council of Ministers held a “special session” to discuss obtaining further financing for this project. A number of backers had already committed to supporting the Diama-Manantali project at the 1974 Nouakchott meeting, but not all major sources of financial support supported the plan. The World Bank was conspicuously disinterested and had sent representatives from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development to meet with the OMVS only “after numerous hesitations.” While the World Bank was skeptical about the project, especially the more costly Manantali Dam, the meeting minutes noted, “it would be appropriate to not discourage the bank and to note with satisfaction its interest in agriculture.”Footnote 30 The OMVS was correct to identify agriculture as the World Bank’s investment priority for the drought- and famine-stricken Sahel; the World Bank digital archive for Senegal, Mali, and Mauritania contains a number of reports and studies about irrigation and agriculture, but none specifically focusing on dams.Footnote 31 An overriding focus on agriculture did not neatly match the goals of the OMVS, which still included a hydroelectric dam at Manantali. Its official view, recorded in meeting minutes from a 1978 reunion of the Council of Ministers, was that “the regional infrastructure program is a coherent whole that must be accomplished as the first step of basin development.”Footnote 32 Nonetheless, the OMVS understood that couching proposed development programs in terms of agriculture and food security carried greater weight with potential donors, and emphasized such benefits the two-dam project offered. In the case of the World Bank, however, OMVS’s overtures did not succeed, and the World Bank declined to finance either Diama or Manantali. World Bank disinterest was a blessing in disguise, however. In the absence of any one large donor, the OMVS retained a high degree of control over the operation and management of the Diama and Manantali Dams.

The USAID demonstrated greater enthusiasm than the World Bank for the integrated management of the Senegal River. When the OMVS held its 1974 financing meeting in Nouakchott, Mauritania, USAID proposed conducting a detailed evaluation of the potential environmental impacts of the integrated development program. Negotiations between the OMVS and USAID took time, but on February 25, 1976, the two parties signed a contract for detailed studies.Footnote 33 The next few years saw an explosion in the number of studies and plans for Diama and Manantali. They also clarified the provisional costs for the projects. One 1980 joint document estimated the costs for each dam: USD109.3 million for Diama, and USD413.6 million for Manantali.Footnote 34 By the early 1980s, the OMVS had assembled a mix of funding sources sufficient to fund the dams. The list of donors for Diama captures the diversity of funding sources, as well as emphasizing how no one donor predominated (see Table 1).Footnote 35 While the funding landscape for Manantali is messier, it shares these characteristics with Diama.

Table 1. Diama Funding Sources (UCF=1.11 USD in 1979).

The high level of financial support from the Middle East is notable, with Saudi Arabia the single largest donor. Bilateral aid from Arab states to the Sahel was a significant source of financing during the 1970s and 1980s. Middle Eastern aid to African countries had origins in Nassar’s close connection to nationalist leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah, Modibo Keïta, and Sékou Touré. The amount of aid grew after 1973, when spikes in oil prices led to increased capital availability in Arab oil-producing states and a severe lack of capital in Western Sahelian nations. Offers of aid further increased after a 1977 Cairo Summit focusing on Afro-Arab solidarity (Founou-Tchuigoua & Zarour Reference Founou-Tchuigoua and Zarour1986; Zarour Reference Zarour1986a, Reference Zarour1986b). Arab donors to the OMVS program accounted for a significant percentage of the total funding for the project, and 94 percent of aid from the Middle East occurred between 1980 and 1984, a reflection of how the program was a major priority for this subset of donors. As with the broader set of the program’s bilateral aid donors, Arab donors prioritized promoting food security, which included emphasizing irrigation and related hydrological interventions, rather than hydroelectric development (Zarour Reference Zarour1986a:268–75). Aid between sub-Saharan Africa and Arab states is an enormous topic deserving of separate consideration, but one possible explanation for Arab donors’ interest in food over energy production is that they hoped to continue to export petroleum to West Africa in exchange for agricultural production.

The OMVS secured funding to construct two major dams on the Senegal River through selling donors on an integrated river management plan that would provide the best medium- and long-term solutions to drought in the Sahel. Financial support began to coalesce in 1974, and by 1976 the OMVS had enough backing for extensive studies on Diama, Manantali, and the Senegal River basin as a whole. Construction began on both dams in the early 1980s; Diama was completed in 1986 and Manantali in 1988, resulting in the successful implementation of a river basin-wide development program. This did not occur by happenstance, but rather through the strategic reshaping by the OMVS of its development program around food security. Through producing knowledge emphasizing food and agriculture in the form of contracted studies or reports, sometimes conducted by external partners, a kind of feedback loop emerged wherein enhanced food supplies supplanted other considerations such as navigability or energy production. The next section of this article will look at these studies, using digital analysis to demonstrate that the OMVS and its partners generated information that prioritized the integrated development program’s food security benefits.

Digital Text Analysis: Methodology and Findings

The previous section showed how the 1970s famine and international concern about food security in the Sahel led to the implementation of an integrated river management plan in the Senegal River basin that emphasized agricultural concerns. The Diama and Manantali Dams were the centerpieces of this plan, and the OMVS required funding from a diverse set of international donors in order to implement it. Through a close examination of OMVS documents, particularly meeting minutes, summaries of resolutions, and internal strategy documents, the first portion of this article demonstrated that there was a purposeful shift in emphasis from the benefits of a river basin development program for energy, navigation, and food security to a predominant focus on agriculture and food production. Looking closely at these planning documents and studies points to the reason for this shift, which was the clever leveraging by the OMVS of the increasing emphasis on the importance of food among an international community of financers and donors in the context of famine.

This section considers the knowledge production practices of the OMVS before, during, and after the famine by analyzing the language with which studies conducted and/or commissioned by the OMVS explained and discussed river development. In particular, it tracks language related to food security and famine, and how this compared to the use of language related to industrial development, energy production, and navigation. This analysis shows that the OMVS responded to both pressing food security needs and international funding priorities by emphasizing agricultural production.

There are strengths and limitations of digital text analysis. The greatest strength inherent in bringing computing power to textual data is the ability of computers to identify trends and patterns far more quickly than the unaided human eye (and brain). This is particularly helpful with massive digital source bases, such as the repository of Foreign Records of the United States or the World Bank digital archive. Digital methods also facilitate the quantification of qualitative data. However, these methods should be used judiciously. In an intellectual climate that increasingly privileges quantification as “real knowledge,” it can be tempting to prioritize quantifiable results as more valid than qualitative insights. This is a great disservice to the nuance and sophistication of qualitative methodologies. Furthermore, the majority of extant text analysis approaches utilize a “bag of words” methodology, relying on the analysis and statistical manipulation of word counts. However, these methods only count the relative frequency of words in a corpus and have limited ability to look at context. For this reason, a strategy mixing qualitative and quantitative methods is often the most prudent approach.

It is also important to acknowledge the limitations and potential issues with the source base or corpus. Corpus means the set of written texts that form the group of analyzed documents. While all the documents are from a cogent genre (studies), they are not homogenous, and they vary in length and emphasis. Some documents focus on the entire Senegal River development program, while others have a narrower theme such as navigation or agriculture. Therefore, the documents are not comparable on an individual basis, but can be compared as part of a larger set. Furthermore, while efforts have been made to consult as complete a set of documents as possible, the corpus may not and likely does not contain every study the OMVS conducted or commissioned. This requires a measure of caution about the comprehensiveness of the results, although they still may reflect significant trends in the deployment of language by the OMVS.

This text analysis has 64 unique documents in its corpus, totaling 8371 pages. The documents are all studies such as environmental impact assessments, economic evaluations, agricultural studies, industrial development analyses, and navigation studies, and they all were either produced by or for the OMVS. The 64 documents in the corpus began as Portable Document Format (PDF) files, which first had to be converted to text files (.txt) prior to the quantitative analysis. This was accomplished using Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software, specifically the program ABBYY FineReader. Once the PDFs had been converted to .txt format, analysis of the documents as a set and over time became possible.

Not all of the 8371 pages, however, were suitable for text analysis, and the documents were therefore curated prior to analysis, a process called “data cleaning.” Data cleaning entails removing pages in the documents that could not be interpreted for textual content. The pages removed included, in descending order of prevalence, pages that included greater than 50 percent of either visual information (such as blueprints or photographs), tables and charts that may have contained alphanumeric information but generated too many errors when converted from PDF to .txt files, and pages that were damaged or had other issues that rendered them unreadable to OCR software. Furthermore, text analysis tools exist for numerous languages. Since they rely on machine learning, the most sophisticated are for English language texts. However, effective code also exists for French. Because the code is language-specific, it is important that the corpus be entirely one language. The vast majority of documents used here are in French, but occasionally the text switches to English within a French-majority document. PDFs were therefore also cleaned to remove English-language content.

It is beneficial to conduct the data-cleaning process prior to converting the information to .txt files, as conversion can take significant time and computing power, and it is difficult to remove errors after the fact. After data cleaning, the text analysis contained 4,606 pages of text. This is a relatively small corpus, making it difficult to prove causality between the shifting language of the OMVS and its successful acquisition of funding. However, correlating the digital analysis with the close reading in the previous sections nonetheless yields worthwhile analytical payoff, specifically a more precise quantification of trends and a model that, if expanded to a greater set of OMVS documents or incorporating documents from similar organizations like the CILSS, could potentially advance to evidence of causation in subsequent research.

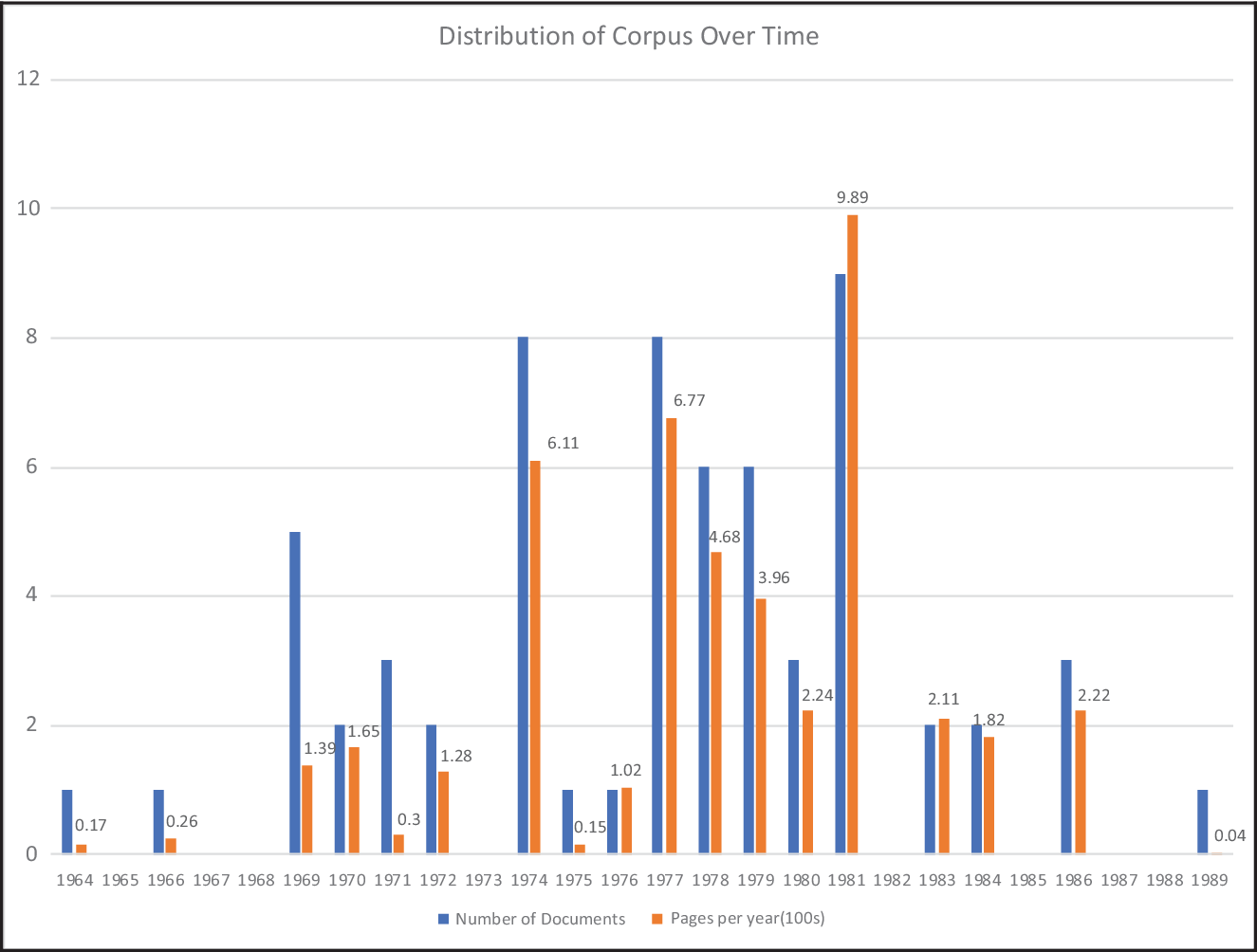

The dates of the documents in the corpus range from 1964 to 1989 (see Figure 2). There is therefore a set of documents from before the drought, as well as a set of documents during and after the drought. For the sake of comparison of before versus after the drought, documents from before 1975 will be considered pre-drought, and documents from 1975 and later are taken as after the impact of the drought is felt. This is justified for the following reasons: studies typically have a span of several years between their inception and the publication of results, so early-1970s studies are less directly impacted by the drought. The OMVS held its first explicit anti-drought mobilization activities in 1974 (the Nouakchott funders’ meeting), so considering 1975 and later documents as one group maps onto institutional change. Using this division, there are 22 documents from the pre-drought set, totaling 1,116 pages, and 42 documents from the post-drought set, totaling 3,490 pages.Footnote 36 The unevenness between the sets calls for caution when interpreting the changes in language. However, the larger number of documents following the drought is preferable to the inverse since it provides more data for understanding how the OMVS and its partners couched the benefits and objectives of development planning during and following this climatic event. The documents are drawn from two archives: the OMVS institutional archives in Saint Louis, Senegal, (OMVS-CDA) and the internal archives for the Société de Gestion et de l’Énergie de Manantali (Manantali Energy and Management Company or SOGEM) located in Bamako, Mali.Footnote 37

Figure 2. Distribution of corpus over time. Number of documents per year (blue) and hundred-pages per year (orange).

The method used is a lexicon-based or dictionary-based approach. This relies on counting the occurrence of words from a predefined lexicon. In this case, the lexicon involves words related to food, including vocabularies related to crops, livestock, irrigation, and nutrition, as well as navigation and energy production and industrial vocabularies. These three prongs mirror the three-fold mission of the OMVS. A dictionary-based approach is useful for tracking occurrences of language surrounding food security. Dictionary-based analysis text has been criticized for mischaracterization when used for sentiment analysis because of the contextual variation of the positive or negative polarity of specific words (O’Connor Reference O’Connor2011). However, these issues usually occur when researchers import dictionaries from other applications to their own work, and the integrity of a dictionary can be maintained if scholars create specific word lists applicable to their particular problem, as has been done here. It is nonetheless important to validate the findings from dictionary-based methods in other ways, because dictionaries can often be skewed or misrepresent trends (Grimmer & Stewart Reference Grimmer and Stewart2013:8–9). In this article, validation occurs through comparison with the results from the previous section.

Dictionary-based methods require attention not only to the frequency (word count) of terms, but also to their relative frequency. Measuring the relative frequency of key words (or word stems) shows their occurrence over time and mitigates the fact that documents within the corpus are of greatly varying lengths, because whereas frequency shows the number of times a particular term or stem is used as an absolute value, the relative frequency shows the occurrence of a term or stem as a number of times it appears compared to the total number of words, and it is expressed as a percentage or proportion.

Word stems can be used to account for related words that speak to the same concepts. Tracking the relative frequency of following three word stems, agri* (for agriculture-related vocabulary including words such as agriculture and agricole), industr* (for industry-related vocabulary including words such as industrie and industrielle), and naviga* (for navigation-related vocabulary including words such as navigation and navigable), is a proxy for understanding the shifts in emphasis on the three key development priorities of the OMVS.

The word stem agri* was, on the whole, discussed at a similar relative frequency from the 1960s until 1974. From the mid-1970s until the early 1980s, a number of documents began to mention agri* with much higher relative frequencies. After 1981, agri* returned to the same as or slightly below its pre-drought relative frequency (see Figure 3). This indicates that during the period immediately following the drought, OMVS studies and planning focused on agriculture and food production to a greater degree than before. At times for the entire period there are points where the relative frequency of agri* approaches zero. This is because that specific document had a focus on a different aspect of Senegal River development. What is important is how over time a higher number of documents mentioned agri* with greater frequency. The relative frequency of another word stem related to agriculture, riz* (for rice-related topics such as riziculture and riz), supports this conclusion (see Figure 4).

Figure 3. Relative frequency (proportion of total words) of agri* over time.

Figure 4. Relative frequency of riz* over time.

A separate visualization must be made for riz* since it cannot be subsumed in the stem agri*. Rice-related vocabulary represents an important subset of discussions and studies about agriculture, as there had been interest in enhancing rice production in the Senegal delta and middle valley, especially since the end of World War II. The need to conduct a separate analysis of riz* reflects one limitation of this methodology: not all words under a topic can be consolidated into a single stem, and therefore measuring the full relative frequency of a topic would require summing the value of all related terms.

Comparing agri* with indstr* and naviga* further supports the conclusion that agricultural concerns were more important to the OMVS and its funders during and immediately following the drought than industrial development and navigation improvements (see Figure 5). There are only two points where industry-related terms had greater relative frequency than agricultural terms, in 1980 and 1981. However, agricultural terms were higher in relative frequency for the majority of the period, especially in the period after 1976, following the launch of intensive studies with USAID funding. Plotting agri* alongside énerg* (for energy-related words, such as énergie and énergetique) and électr* (for electricity-related words such as électricité or électrificiation) also shows the predominance of agricultural vocabulary. Even if the relative frequencies of this set of industry-related terms were added together, they would still be far less relatively frequent than agricultural vocabulary.

Figure 5. Relative frequencies of agri* (pink) and industr* (orange).

It might be surprising that industry terms have a low relative frequency compared to agricultural terms in the pre-drought period. This conflicts with the theory that the OMVS opted to subordinate industrial development in favor of agriculture due to drought and famine. However, looking at the relative frequencies of agri* compared to industr*, énerg*, and électr* for the pre-drought documents (1974 and earlier) shows that these vocabularies had similar weights for this era, and that a greater divergence began in the mid-1970s (see Figure 6). Another possible explanation is that the predecessor organizations to the OMVS, the CIE and OERS, were not able to consider large-scale energy production programs, given their limited budgets during the 1960s, and it was only after the increase in international attention and funding that the Manantali project and attendant industrial planning got meaningfully underway.

Figure 6. Relative frequencies of agri* (pink), électr* (teal), and énerg* (light green).

Finally, the results of comparing naviga* and agri* are intriguing, as they show a high relative frequency of navigation-related terms (see Figure 7). This result is surprising for several reasons. While navigation has implications for food security and famine relief, particularly regarding the distribution and transport of food goods, it is not directly related to a vocabulary of nutrition and health. Furthermore, although navigation was one of the three priority areas for the OMVS, minimal investment or infrastructural development occurred in this domain in the 1970s, 1980s, or later. However, the fact that navigation has a higher relative frequency than agricultural terms for much of this period suggests a few important conclusions. First, it exemplifies the gap between planning and implementation. It is critical to remember that the corpus represents studies; in other words, records, recommendations, and potential plans, not necessarily results or actions. The disjuncture between the prevalence of navigation vocabulary in the corpus and the lack of implementation of navigation programs exemplifies this aspect of development planning. Second, another possible explanation for navigation’s having a higher relative frequency is that its vocabulary was likely to co-occur in discussions of both agriculture and industrial development. For agriculture, the kinds of intensive expansion of cultivation that the OMVS hoped to accomplish required enhanced riverine transport. The same was true for the hoped-for industrial benefits of the Manantali dam. This likely explains why navigation appeared so often in documents despite it not being a priority area for implementation.

Figure 7. Relative frequencies of agri* (pink) and naviga* (purple).

Conclusion

Drought and famine in the Sahel have been persistent scourges for West African nations. The drought during the early 1970s derailed regional economies, displaced vulnerable populations, and weakened recently independent nation states. It was indeed, as the Atlantic journalist put it, “a calamity of biblical dimensions.” Yet, one transnational river development organization, the OMVS, managed to turn the crisis into an opportunity, obtaining funds to implement an integrated river development project centered around the Diama and Manantali Dams. It was able to do so because of the conjuncture of a comprehensive management program for the entire river basin with unprecedented international donor interest in preventing future climate-caused famine in the region. The success of the OVMS shows that the impact of the 1970s drought on African sovereignty was not uniformly negative, and it did not necessarily lead to a weakening of political capacity.

The promise of enhanced agricultural production and greater food security were the greatest selling points of the OVMS’s plan. This is shown both in how the OMVS presented the benefits of the Diama and Manantali Dams and in the language and content of the studies that were carried out or commissioned by the OMVS. Combining close reading of OMVS institutional sources with a digital analysis of studies shows the predominance of agricultural considerations for Senegal River development in different ways. The qualitative analysis in part one of this article explained why the OMVS decided to pitch its integrated river basin management project in terms of food security. It also described how this, alongside the creation of robust fiduciary infrastructure, led to increased financing for river development. The quantitative analysis in the second part of the article indicates that this strategic focus on agriculture also manifested in the pages of OMVS studies, highlighting how the OMVS’s process of knowledge creation and sharing mirrored its strategy for attracting funding. While this study cannot prove causation between the changing language in OMVS documents and the successful financing of OMVS development projects, it enriches insights from a close analysis of the OMVS’s operations and planning and allows us to see trends in a different way.

An approach that combines deep historical contextualization, close reading of sources, and the judicious use of digital analysis is a promising strategy for understanding important trends in African history and policy. Combining these approaches is not a matter of quantitatively “proving” what can be gleaned from reading documents, but rather it illustrates how mixing methods provides further texture and context for understanding trends. Such an approach is promising for research dealing with large, digitized source bases and offers exciting avenues for future inquiry.

This article opened with a puzzle: how did the OMVS gain the resources to implement an ambitious, river basin-wide development program, and manage to do so without losing authority over the use and management of riverine space? The timing of the OMVS program’s conceptualization and implementation is crucial, with financing occurring during the late 1970s. This was the period when OMVS member states began to fall into debt, setting the stage for structural adjustment programs that represented grave challenges to national sovereignty. Looking at documents in two ways, first through more traditional close reading and later via distant reading utilizing digital methods, this article shows that the OMVS managed to leverage international attention directed to the Western Sahel. Presenting itself as a reliable, transnational body that was able to overcome the perceived limitations of its individual member nations, the OMVS channeled donor enthusiasm for promoting food security, recasting older development programs that balanced agriculture, navigation, and energy production as focused on food security alone. This deft management of donor interests enabled the OMVS to implement its program while at the same time retaining control of the river basin’s developmental agenda.

Acknowledgments

The author appreciates the thoughtful comments from the anonymous reviewers and editors which substantially improved the manuscript. Funding for portions of this research came from the Stanford Center for African Studies, the Fulbright-Hays DDRA, and the West African Research Association. The author extends special thanks to the Stanford Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis and Regina Kong, as well as to the Stanford University Africanist community. All errors remain mine.