With the breakdown of colonial-era work regimens, growing land shortages in rural regions, and the out-migration of women accompanying men to urban sites, post-colonial migration in many regions of Africa takes on myriad forms, often distinctly different from the classic colonial-era circulatory patterns that the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute so astutely examined in the 1940s and 1950s (Wilson and Wilson Reference Wilson and Wilson1945; Richards Reference Richards1977). Contemporary sub-Saharan African urban residents exist along a continuum, ranging from recent arrivals who continue to view their rural region as home, to urbanites who have lived in the city for years, or perhaps generations (Potts Reference Potts1995; Cooper Reference Cooper2002: 149). Much of the rural–urban movement documented in recent years defies the classic pattern in which men work in the factories and mines, while women remain behind to run the farm (Potts Reference Potts2000). Often, it follows neither a consistent back-and-forth circulatory pattern, nor a simple teleological trajectory from transient rural labour migration to permanent urbanization (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1999: 42–4). Rural–urban movement instead reflects sporadic and episodic economic crises and political instabilities endemic to Africa in recent years (Linares Reference Linares2003).

Despite the diversity of rural–urban movement, there is nevertheless widespread acknowledgement that even those who have lived in the city for years, or generations, maintain some sort of orientation towards their rural region of origin (Cheney Reference Cheney2004). Such links to a rural homeland often serve as forms of resistance to proletarianization (Bank Reference Moore1993), may still be places to turn to for ceremonial occasions or burial (Gugler Reference Gugler2002; Cohen and Odhiambo Reference Cohen and Odhiambo1992), or sometimes represent little more than a point of nostalgia and collective memory (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1992). Van Binsbergen calls these highly symbolic connections to a rural homeland ‘virtual’ culture, representing ‘cultural material from a distant provenance in space or time’, often fragmented and de-contextualized, ‘yet with formal continuity shimmering through’ (1998: 878). Such virtual culture reaches beyond feelings and sentiments about a rural past – for an urbanite contemplating farming after a long hiatus, it also may aid in the reproduction of material conditions that serve as components in an urban domestic economy.

This article documents the process through which two post-colonial peri-urban settlements of northern and western Kinondoni District of Dar es Salaam developed over a period of fifteen to twenty years. The present study specifically focuses upon individuals who lived in the city for a decade or more, drawing from a repertoire of socio-cultural forms to create their distinctly urban households. Subsequently, they moved to its peri-urban fringe, either to recreate the ‘garden suburbs’ of their former colonial rulers, or to engage in urban farming as part of a strategy of economic diversification (Berry Reference Gugler2002; Mortimore Reference Mortimore, Moss and Rathbone1975; Simon, et al. 2004; Nkambwe and Totolo Reference Nkambwe and Totolo2005). The farms they created bore some resemblance to those found in the north and west of Tanzania, where many of them originated before moving to Dar es Salaam over a decade earlier.

However, looks can be deceiving – in spite of similarities with their rural counterparts, urban farms incorporated elements of urban infrastructure and culturally salient configurations familiar to other kinds of urbanites. Though cities continually experience spatial transformations, the emergence of new urban social institutions, or the replacement of personnel through migration or decolonization, urban relations of power often turn out, in the end, to reproduce pre-existing, distinctly urban, patterns (Mabogunje Reference Mabogunje1990). While peri-urban farming emerged as a strategy of economic diversification during Tanzania's period of state socialism, social relations of production in these peri-urban areas wound up resembling those of urban neighbourhoods closer to the city centre, as increasing numbers of urbanites moved from the city to its periphery after privatization received official sanction following the Zanzibar Declaration of 1991. Peri-urban settlement and urban farming are not necessarily evidence of poor or incomplete adaptation to urban life.

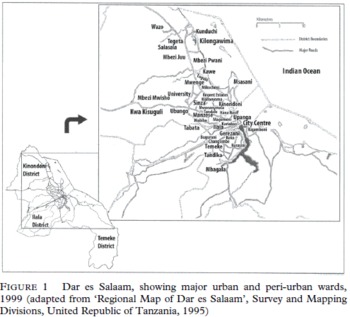

This study is based on fieldwork concentrated in two areas of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The first is Mbezi block ‘L’, known locally as Kilongawima, approximately twenty kilometres north of City Centre. The second area is known as Kwa Kisuguli, located about twenty kilometres west of City Centre on the Morogoro Road. As of the 2002 Tanzania census, Kwa Kisuguli was still within the jurisdiction of Mbezi Centre, the former Ujamaa village of Mbezi, now an urban ward within Kinondoni District, with approximately 10,000 inhabitants. Kilongawima became a separate urban ward in 2000, and had a 2002 population of 4,174 (United Republic of Tanzania 2004).

THE SUBURBAN VANGUARD'S UPCOUNTRY ORIGINS

From Dar es Salaam's founding in the 1860s until the late 1950s much of the growth of the town's African community derived from movements of ethnic groups originating in surrounding regions (Owens Reference Owens2006; Vincent Reference Vincent1970). Many were active participants in circular migration, while others were long-time residents, whose settlements were incorporated into the city's expanse as Dar es Salaam grew (Brennan and Burton Reference Brennan, Brennan, Burton and Lawi2007: 44–51; Swantz Reference Swantz, Swantz and Tripp1994). Immigrants from outside Tanganyika also contributed to urban growth (Brennan Reference Brennan, Brennan, Burton and Lawi2007). There was also a small semi-skilled professional class serving as mid-level clerks and educators in the colonial regime (Leslie Reference Leslie1963).

Immediately before and after Tanzania's independence in 1961, decolonization necessitated replacing the British colonial civil service with African government employees. New opportunities arose for the development of a professional class in Dar es Salaam's civil service and parastatal sectors. This gave rise to a shift in the pattern of urban in-migration throughout the Reference Curtis1960s; a great many more urban migrants came from more distant regions of Tanzania. Many of those participating were products of the educational system in these more remote districts. Most indicated that they intended to stay in the city on a permanent basis (Tripp Reference Tripp, Swantz and Tripp1994: 103; Sawyers Reference Sawyers1989: 841–60).

The Chaga, Haya and Nyakyusa are well represented among those arriving to take advantage of the decolonization of the civil and parastatal sectors in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as among the earliest participants in the subsequent growth of peri-urban districts of Dar es Salaam. Each of these groups came from different regions of Tanzania. But as van Binsbergen points out (1993: 186), though African urban migrants may represent a diverse array of ethnic groups, each with its own unique set of cultural values and subsistence strategies, they often share general underlying cultural experiences that serve as a ‘substratum’ for forging a cosmopolitan urban identity. Common dilemmas governed not only the manner in which they participated in decolonization, but also their willingness to join a small group of individuals relinquishing many of the comforts available in the urban centre to pursue farming early in the development of Dar es Salaam's outlying districts. Their experiences are illustrative of how translocal experience may have contributed to shaping the configuration of peri-urban areas.1

Historically, the Kilimanjaro Region of north-eastern Tanzania, where the Chaga originated, was a central locus of nineteenth-century caravan routes and a refuge for a diverse array of peoples from this part of East Africa. Bananas were and remain an important subsistence crop in a region with a relatively cool and moist climate, and watered by streams flowing from Mount Kilimanjaro. Residence was based on the kihamba, a localized patrilineal cluster of houses and compact banana groves on ancestral land (see Moore 1986: 82–3). The Chaga also benefited from cross-border trade with neighbouring Kenya. As the colonial economy became increasingly dependent on coffee production, and the population grew, land became a valued and scarce economic resource (Moore Reference Moore2005: 262). At 103 persons per square kilometre, the Kilimanjaro Region is currently the third most densely populated mainland region of Tanzania (United Republic of Tanzania 2006: 12).Footnote 2 Because many vihamba had been subdivided over generations, young people today are far less likely to inherit a viable plot of land on which to farm. Many parents see providing children with education as a substitute for farming in a region with an increasingly scarce land base (Stambach Reference Stambach2000). As of 2002, Kilimanjaro had the second highest rate of literacy after Dar es Salaam, and highest level of school completion. But it has also experienced a net out-migration – by individuals of all educational levels (United Republic of Tanzania Reference Lewinson2006: 57–66, 152).

The Kagera Region where the Haya originated is blessed by ample rainfall, but has irregular fertility. Rural villages in Kagera consisted of a collection of vibanja, in which an individual family's plot seldom exceeded two hectares of densely intercropped land containing bananas, fruit trees and coffee – their principal cash crop (Reining Reference Reining1967: 53–60; Weiss 2003). Villages were clustered and land intensively fertilized, either with manure obtained from pastoral peoples living in the abundant neighbouring grasslands, or with grass cut and carried to farms from drier open lands surrounding villages (Curtis Reference Curtis1989: 42). The result was an agricultural village in which homesteads press tightly upon one another beneath a canopy of banana, fruit and coffee trees, punctuated by fences surrounding trails leading to individual houses and courtyards.

Fourth in population density at 71 persons per square kilometre, Kagera District has also had limited room for expansion. The Haya tended to practise patrilocal residence, with sons and unmarried daughters living in their fathers’ households. While the agricultural system represented an essential part of the economy, most Haya men and women did not depend exclusively on agriculture but also participated in small trade, the fishing economy of the Lake Victoria-Nyanza region bordering on Uganda and Kenya, and beer brewing (see Weiss 1997). Currently, many out-migrants choose Bukoba town or neighbouring Mwanza as a destination of choice, and many Haya residents of Dar es Salaam started their careers in one of the towns or cities in the north-west.3

The Nyakyusa originated in the western highlands of Mbeya Region, bordering Lake Malawi in south-western Tanzania, which also enjoys abundant rainfall and ample fertility. They relied on plantain and bananas as staple crops, and the kaaja or family grove served as an important marker of household prosperity as well as an ancestral burial site (Maruo Reference Maruo2007: 22). They also engaged to a lesser extent in millet cultivation and kept cattle and pigs. After the Second World War cash crop cultivation, especially coffee and rice, became increasingly important to the local economy. As commercial farming developed, demand for land began to outstrip supply, resulting in a general shortage (Gulliver Reference Gulliver1958: 3). While the 2002 census reports that Mbeya Region as a whole was not nearly as densely populated as Kilimanjaro or Kagera, the Nyakyusa are concentrated within the districts of Kyela, Rungwe and Urban Mbeya, with population densities of 72, 138 and 1,440 per square kilometre, respectively (Planning Commission 2009: 12; United Republic of Tanzania Reference Lewinson2006: 3).

In the early colonial period, the power of Nyakyusa chiefs and elders centred upon control of prestige trade goods and cattle for bridewealth. As the century progressed education led to skilled employment and wage labour opportunities outside Tanganyika, opening alternative avenues of prestige and wealth for young men and women (Wilson Reference Wilson1977: 63–4). Young men became active participants in circulatory labour in the mining industries of Rhodesia and South Africa, postponing marriage and the acquisition of land until their elders were ready to retire (ibid.: 183–4). This option was abruptly cut off when the post-independence government of Tanzania closed its borders in 1964 and forbade migrant work in Southern Africa (Willis Reference Willis2001). Land shortages, combined with diminishing wage labour opportunities, prompted many men and women to seek opportunities in other regions of Tanzania, including Dar es Salaam.Footnote 4

Aside from the fact that many who first settled in the peri-urban districts of Dar es Salaam were part of an emerging educated professional group – a quality they shared with many other post-independence migrants to Dar es Salaam – three other common characteristics seem to tie them together. First, they came from regions where fertile land was a scarce resource, and viewed as an important basis for economic and community development. Though predominantly rural in origin, their regional economies were also tied to secondary urban areas, translocal trade networks and labour migration routes to neighbouring countries. This suggests a pre-existing familiarity with a repertoire of strategies of socio-economic diversification that would end up serving them well in urban Dar es Salaam. Given pressure for scarce resources, diverse sources of income, and emerging cultural forms that challenge conventional social structures in rural areas, urban migrants now have little if any rural existence to return to even if they had so wished. Though many expressed their wish to be buried on ancestral land, and a few hoped to build a house on or near their ancestral farmstead, virtually none contemplated returning to a rural life in their home regions anytime soon.

AFRICAN SOCIALISM: THE BEGINNINGS OF URBAN–RURAL MIGRATION

By the mid-1960s, this influx of upcountry educated individuals into Dar es Salaam laid the groundwork for an emerging urban educated elite. They joined the workforce in significant numbers, and successfully adapted to urban life. However, in 1967, President Julius Nyerere implemented the Arusha Declaration, making socialism, or Ujamaa, Tanzania's ‘official’ policy. This abrupt shift in national policies had profound effects on Dar es Salaam, making land available for urban farming on its periphery, and creating conditions motivating many urban residents to leave the central city. Rather than returning to their regions of origin, members of the urban vanguard sought land in Dar es Salaam's periphery, ultimately contributing to the city's expansion.

Around 1969 or 1970, government representatives travelled throughout Tanzania's 21 mainland regions, declaring government intentions to form Ujamaa villages, a kind of concentrated collectivist agricultural settlement. Those living in scattered homesteads would move to the villages, where they could live together and engage in cooperative agriculture. By 1973, the government had changed Ujamaa policy from a voluntary system to an enforced one (Coulson Reference Coulson1982: 270–1), and eleven million people were moved into nucleated settlements (Fortmann Reference Fortmann1980: 33). Operation Pwani, designed to implement this forced relocation in the Coast Region surrounding Dar es Salaam, was more or less completed by 1975 (Mesaki Reference Mesaki1975: 82).

Before Operation Pwani, most farmers of the Coast Region engaged in swidden cassava, millet and rice cultivation in scattered homesteads. A few urbanites also kept garden plots or second homes on the city's periphery. North and west of the city, concentrated informal settlements had already sprung up on transit points along major roads, or near local centres of employment like concrete works, sisal plantations, tourist hotels and military barracks. In the Coast Region, the government located many Ujamaa villages on or near these existing settlements. Families living in scattered homesteads saw their homes demolished and belongings sent to the location of the new Ujamaa villages, where land redistribution was limited to a few garden plots adjacent to their new residences.

Aside from being required to participate in cultivating village block farms, farmers continued cultivating their original farms, provided that they returned to their Ujamaa villages each evening. Relocation presented little difficulty for those who had been moved only a short distance from their original farmsteads. But those resettled into villages some distance away sometimes had to walk for several hours to tend their crops. Many gave up cultivating altogether. One unintended consequence of forced villagization was a near collapse of agriculture throughout Tanzania (Scott Reference Scott1998: 223–60); another was that on the outskirts of Dar es Salaam land that formerly had been worked by local farmers became available for cultivation.

With the near collapse of agriculture following the implementation of socialist villagization, the government's top priority was to encourage citizens to engage in any kind of farming activity that could ameliorate the loss of production, including urban agriculture and animal husbandry. In Dar es Salaam, the government implemented Operation Kufa na Kupona (Death or Recovery) in 1974. Although regulations limited farming and animal husbandry within city limits, both to promote sanitation and as a mosquito control measure, the government made land available on Dar es Salaam's outskirts to those employed in government offices and factories (Bryceson Reference Bryceson and Guyer1987: 190). The government tacitly encouraged many non-government employees to cultivate any unutilized open spaces in or around the city (Kulaba Reference Kulaba, Stren and White1989: 225).

Urbanites enthusiastically seized opportunities to both feed their families and produce marketable crops in the Dar es Salaam Region. One reason for this interest in urban farming is that key industries were nationalized after the Arusha Declaration. By 1976, 65 per cent of wage employment was in the hands of the government. Wanting to reduce the gap between rural and urban incomes, it implemented wage controls in the industrial and parastatal sectors (Tripp Reference Tripp, Swantz and Tripp1994, Reference Tripp1997: 40–3). Many individuals decided to quit paid positions and try their fortune in private businesses. Others found it essential to supplement incomes by engaging in informal business activities including farming and animal husbandry. Tripp cites a survey sponsored by the World Bank in 1974 which noted that, while many individuals cultivated small gardens in the vicinity of their homes, few identified themselves as farmers. By 1988, more than half the residents of Dar es Salaam engaged in urban farming (Tripp Reference Tripp1997: 39).

Both planned and unplanned settlements on the city's edge attracted residential urban farmers. The land was a component in a much broader and flexible household economy, including garden crops for household consumption, cash crops for urban markets, animal husbandry, and petty trade – all in addition to wages from employment in Dar es Salaam. Should crops fail or wages stagnate, householders could temporarily withdraw from the weaker components of their household economy, and put more energy into stronger ones. Urban farming was part of what Camillus Sawio has termed a ‘logic of survival’, governing urban wage earners’ decisions to diversify income-generating strategies during the economic crises of the 1970s and 1980s (1994: 46).

In a 1990–1 survey of 260 urban farmers in Kinondoni, Mwananyamala and Msasani, urban wards of Kinondoni District about 7–8 kilometres from the urban centre, Sawio found that, while urban farming was practised by representatives of all socio-economic strata, farming was not evenly distributed among them. Members of his sample tended to be well educated relative to the urban population as a whole, with 65 per cent having completed O-level education (1994: 38). He also found that the top two occupational categories to which most urban farmers belonged were small business or trade operators, and professionals (teachers, doctors, architects and other high-skill occupations). His survey results also suggested that those who cultivated or practised animal husbandry in the more remote, medium-density areas of Msasani and Regent estates tended to occupy high posts in the Tanzanian government (1994: 43).

By the 1980s, a few adventurous individuals had moved out further into the city's periphery, to sparsely settled and unplanned areas 10–25 kilometres north and west of the centre of the city. Only a limited number of urbanites were enamoured with the prospect of living on a farm located at a remote distance from the city centre. As one member of the vanguard described it, they were somewhat mockingly referred to as washamba – roughly the equivalent of ‘bumpkin’. Considering the distances between their urban residences and the remote areas in which they intended to relocate, the vanguard understood that they would sacrifice many comforts of urban life. Bus services were sporadic and other municipal services only extended to the city boundaries and connecting routes along major roads. One long-time resident said that, had he been told then that services such as electricity, telephone service and piped water would some day come to his area, he would not have believed it.

Farmers tended to find themselves in one of two situations: either they were fortunate enough to have secured a garden plot in the vicinity of their residence, or they had a plot located somewhere in the city periphery. The latter found themselves in a situation analogous to that of residents of Ujamaa villages – having a somewhat long commute to and from their residences and crops. In order for the vanguard to commence the transformation of urban farms into peripheral urban settlements, these peripheral plots had to become residential farms.

As urbanites moved north and west of the city, the government drew up ‘master plans’ for city expansion beyond the urban threshold as it existed in the early 1970s. In areas like Kilongawima and Kwa Kisuguli, land from nationalized sisal plantations and grazing lands of the Tanganyika Packers became available for government allocation after these parastatals failed. In other cases, urbanites acquired an interest in farmland that had been used by local Zaramo or Matumbi farmers prior to being relocated to Ujamaa villages. As urbanites expressed an interest in acquiring under-utilized land under the jurisdiction of the village authorities, and village residents were willing to collude with them to transfer rights of occupancy, there inevitably came to be an overlap between the governmental and city authorities, and the Ujamaa villages established just beyond city boundaries.

Through the 1980s, ‘secret sales’ of land became rampant. Urban residents offered local cultivators ‘compensation’ for farms abandoned during villagization. Local Ujamaa village officials and residents typically colluded with urbanites, the latter accepting such compensation, and the former collecting ‘witness fees’ to document the transfer of farms to newcomers. In Kunduchi, village authorities parcelled and sold off their collective block farms to urbanites in what is presently the ward of Salasala. With signed and witnessed documentation of the transfer of a ‘farm’ within the jurisdiction of the Ujamaa village, an urbanite could then go to the Ministry of Lands or City Council to register the land, and have his or her name registered on the master plan map as the current occupant of that plot.

Those with plots registered or surveyed by government in the peri-urban regions of Kinondoni often speak of themselves as ‘owners’ of the land. Strictly speaking, this is a misnomer, since officially only use rights are recognized under Tanzania law. Because the vanguard often had ample economic resources to navigate the legal system in order to press claims for first registry, they were undoubtedly familiar with the government position that land does not belong to them in any Western sense of legal ownership. Because many originated in regions bordering Kenya, Uganda and Malawi, where a private land market is recognized, perhaps their perspective was based on a concept of private ownership of land, which may have been familiar to those who had travelled or had communication with neighbouring countries. Thus, in the near term, urban farming served as a contingency plan in a time of crisis. But in the longer term this strategy positioned residents of these peripheral settlements to maintain and even increase their economic position relative to urbanites not participating in this initial move to the city's periphery.

Case Study: James Mwaijongo5

An early representative of the urban vanguard was James Mwaijongo. He was born in Mbeya Region, where he studied until Standard VII. His father had worked in Zambia for a number of years, enabling him and his siblings to extend their education to this level. Subsequently, he was able to obtain a position in a secondary school in Arusha, where he completed Form IV. He was then hired as a clerk by the Tanzania Tourist Board and later transferred to Dar es Salaam. Through the 1970s, he worked at various tourist hotels along the coast of Dar es Salaam, including one at Kunduchi beach near Kilongawima. He applied for rights of occupancy to a plot at the nearby Ujamaa village of Mtongani in 1980. Echoing familiar rural practices from his home region of Mbeya, he sought out swampy lowlands for commercial rice cultivation. Subsequently, he built a home and planted bananas. In addition to his clerical position and farming, he has also operated a salt pan in the area with a group of investors.

He described a group of elders living in Kilongawima in the late 1970s, who were neither local cultivators (all of whom relocated to Ujamaa villages) nor members of the new urban vanguard. Many had been born and raised in neighbouring African countries, and moved to Tanzania during the colonial period. Shortly after local farmers had been relocated, these elders quickly built houses and established farms in the abandoned fields and thickets of the city's borderlands. It was to one of these elders, a Ugandan by birth, that he paid compensation. Even when Tanzania was fully engaged in villagization in the mid-1970s, these individuals were confident that one day land close to the city would be a target for speculation as the city expanded and demand for land increased. Though many had since died or moved away, their forecasts turned out to be accurate, as land became a scarce and valuable commodity after Tanzania turned away from socialism in the mid-1990s.

URBAN FARMS: A RURAL/URBAN MOSAIC

By the time of my observations in the late 1990s, representatives of upcountry ethnic groups who came to Dar es Salaam had broad experiential knowledge of urban living, having lived and worked in Dar es Salaam as wage earners, business people and civil servants. The vanguard of residential urban farmers, living in Kilongawima and Kwa Kisuguli, had also been settled for as much as a decade or more, with well-established farms in these peri-urban settlements. Approximately one in three households engaged in substantial urban farming, and approximately 85 per cent of urban farmers were from the Chaga, Haya and Nyakyusa ethnic groups described earlier. Other farmers represented various groups from various regions of Dar es Salaam.Footnote 6 Other residents, arriving after the vanguard established itself, had homes, businesses and rental units, but did not engage in substantive farming on the premises.

Most urban farms did not exceed three or four hectares, often separated from neighbouring homesteads by walls or barbed wire fences. Among the three ethnic groups described previously, an overwhelming number divided their farms into two discernible parts. One was an inner garden with bananas and fruit trees, surrounding or adjacent to the main house, suggesting the kihamba, kibanja or kaaja settlements of northern or western Tanzania. Other parts of the farm were kept open, or contained more widely spaced orange or coconut trees, marketable crops requiring ample sunshine, or animal pens and sheds. Though the vanguard's urban farms took on many virtual qualities suggestive of rural farmsteads of upcountry Tanzania, they were not identical copies of upcountry rural settlements. Many observable differences resulted from differential patterns of urban household organization, differences in labour recruitment and utilization, and concessions to the coastal savannah environment in which Dar es Salaam is situated. The following illustrates ways in which urban farmers evoke their rural counterparts, while being firmly ensconced within the urban economy.

Case Study: James Mutalemwa

Many residents view the inner garden as an essential part of the household, suggesting to them the family groves of their home regions. In the course of one conversation with a long-time resident of Kilongawima, we discussed the similarities of his urban banana garden to the kibanja, or Haya farmstead. James Mutalemwa was born and raised in Kagera District, and had the good fortune to secure a position in a Catholic secondary school in Mwanza in north-west Tanzania. He first came to Dar es Salaam and lived with an uncle in Temeke, near downtown Dar es Salaam. He moved to Mwenge in 1979 because Temeke was crowded and expensive, and obtaining clean water was an ongoing concern for residents of the area. At Mwenge, he raised chickens and cattle. However, soon it too became crowded, and neighbours complained about his animals. By 1987, he had acquired land along the Morogoro Road in Kwa Kisuguli because it was near enough to a major transit route to be convenient – he worked as a driver, and later sales representative, for a company providing propane, butane and natural gas to restaurants and hotels in the Dar es Salaam area.

He objected when I used the Swahili term for farm, shamba, to describe his urban farm. While cultivars like bananas and coffee trees that surround a homestead are essential to any kibanja, the difference between a farm and kibanja is that the latter is ‘a place where people live’. A farm, on the other hand, is an open field in which crops are grown on a rotational basis. The bananas belonging to the kibanja had always been there as far as residents’ memories serve, and ‘no one knows who planted them’. They are thus analogous to the families who had lived on the kibanja for many generations, representing an unbroken chain of trees descended from the first ones planted. The kibanja is also where the ancestors are buried, making it inalienable. In a manner evocative of their rural home regions, householders view the peri-urban banana garden as critical to the creation of a true homestead, and not merely a subsistence strategy. A peri-urban plot would hardly be a home without them.

Bananas are propagated by shoots, which mature into a plant producing a single bunch of bananas. When the bananas are harvested, many farmers cut the plant down and leave it as mulch for new shoots that grow at the roots of fallen plants. Within a few years, at least one sector of the urban farm consists mainly of a concentrated canopy of banana trees. Beneath the banana trees, other kinds of plants may be intercropped, such as pineapples, avocado and beans. One family living in Kilongawima even attempted to plant a coffee tree in their household grove, reminiscent of practices in the highlands of northern and western Tanzania. Though farmers kept spindly coffee trees as ornamentals, it was virtually impossible to grow them on a commercial scale in the dry savannah environment surrounding Dar es Salaam.

Case Study: Mama Henry

Like their Haya neighbours, Chaga residents also evoked similarities between the kihamba and the urban banana grove. ‘Mama Henry’, as she is known locally, was born and raised in Marangu, in Kilimanjaro Region. She performed well in school, and eventually earned a position at Morogoro Teacher's Training College. She and her husband went to Dar es Salaam, where she worked as a teacher in Ilala, while he became a container manager for the Tanzania Harbours Authority. Unfortunately, she contracted a serious form of cerebral malaria, compelling her to retire early from teaching. She and her husband moved from Ilala to Sinza in the late 1970s, where they engaged in urban farming. As this district became crowded, they moved to Kwa Kisuguli. There, they maintained a household, but kept the house and land in Sinza as rental property. In 1985, her husband was offered a generous early retirement severance package, which they used to build a chicken coop and invest in raising milk cows.

Mama Henry observed that Chaga urban banana gardens also bore resemblances to ancestral vihamba groves in Kilimanjaro. Even in Dar es Salaam, Chaga women often took responsibility for household maintenance and upkeep of banana groves, while men played a greater role in animal husbandry and cash crop production. In this gendered division of labour, suggestive of households in the Kilimanjaro Region, families kept most harvested bananas for household consumption. Once a grove was well established, however, families often found themselves in a situation in which several bunches ripen about the same time. Women sometimes sold extra bananas not needed for household consumption – but usually limited such sales to close neighbours with whom they were on familiar terms. In one reminiscence, she explained that women could use the money earned as their own personal fund, to be spent as they wished:

If a husband is spending too much time around the house, she sometimes goes to the purse she hid in the kitchen, and takes out some money. She then gives it to her husband and says ‘Take this – go out to the bar with the men and have a good time! I want to be by myself!’

She was explaining that the household was a woman's domain, and that it would have seemed untoward for a man to spend a lot of his time in the company of women. But it also reflected the fact that women were allowed to keep money they earned independently through informal selling to friends, relatives or neighbours. In other instances, neighbours offer bananas as gifts or as a contribution to celebrations. The use of bananas seems to stand in contrast with many other cultivars on urban farms, aimed specifically at urban markets.

However, there is an important difference between the urban banana garden and an upcountry ancestral grove. Residents of Dar es Salaam generally do not bury deceased family members on their urban farms. Instead, most urban residents of upcountry origins go to great expense to arrange transport of the deceased to their home regions, to assure burial among their ancestors. Frequently, when a resident of Kilongawima or Kwa Kisuguli dies, neighbours collect money for a mchango – literally, ‘winnowing basket’, equivalent to ‘passing the hat’ in English. There is often a local memorial service, and contributions are used to ship the body to the deceased's home region. Urban farmers are remarkably vague as to the fate of their farms after they die. The few willing to speak on this subject seemed to have felt that the ambiguity in inheritance rights under current Tanzanian land law means that their children are unlikely to inherit their farms. Instead, they often encourage their sons and daughters to seek educational opportunities in the hope that they will not need to resort to part-time farming like their elders.

Beyond the house and its inner canopy of cultivars, urban residential farmers set aside ample space for crops requiring open sunshine. For many of the urban vanguard, especially from representatives of regions outside of Kilimanjaro, Mbeya and Kagera, their residential farms largely consist of fruit trees and/or rotating open-air garden crops. Okra and mchicha, a spinach-like green vegetable, served as both staples for household consumption and crops that could be marketed in and around Dar es Salaam. Some farmers also supplied food harvested from their commercial fields to tourist hotels dotting the Indian Ocean coast. Some families pooled their resources: for example, while some household members cultivated, others took responsibility for transporting and marketing produce in Dar es Salaam. There is also a growing commercial market beyond the region, including peppers, onions and garlic for export to Europe and the Middle East. As is the case in many rural settlements, open space gardening was critical to the household economy.

In addition to the production of crops, animal husbandry is an important component of these settlements. Even in higher-density settlements close to the city, a householder might keep one or two chickens for eggs or for household consumption. Raising chickens on a larger scale used to be more common in peri-urban areas, until Interchick, a large private conglomerate, saturated the market with inexpensive poultry. Many urban farmers kept dairy cattle, selling milk to wholesalers. Pig rearing represented a very profitable industry at the time of research. In addition to demand for pork from tourist hotels and businesses near the Indian Ocean, many farmers profited through a fad known as kitimoto – many bars and restaurants around Dar es Salaam now serve roast pork meat to customers. Sheep and goats, while commonly raised in the region, are not quite as profitable on a commercial scale – perhaps because of competition with coastal herders living in and around former Ujamaa settlements.

Labour recruitment and utilization on urban farms

Many of the vanguard were professionals, commuting to and from Dar es Salaam and running a variety of small business operations. While a modestly sized urban garden might be maintained by the farmer's immediate family, more successful operations led to a demand for manual labourers to assist them in daily operations. Because land around Dar es Salaam was variously allocated by the Ministry of Lands, the City Council and Ujamaa village authorities, members of extended kin groups living in the city tended to be widely scattered. Though individuals moving to the city often rely on kin to find temporary housing, urban farms were remote from most city services, making them less desirable destinations for relatives from rural regions.

Initially, members of the vanguard recruited herders, housekeepers, farm hands, craftspeople and small business operators who were part of Ujamaa settlements. Migrants settling near roadsides and transit points also provided support to these farmers. Often, members of the vanguard recruited labourers from upcountry ethnic groups reputed to be experts in specialized fields of agriculture or animal husbandry. For example, many householders who kept cattle hired herders who came to Dar es Salaam from the Dodoma Region. Others recruited Sukuma from the Shinyanga District as casual labourers clearing fields and harvesting. Many local businessmen hire Maasai, dressed in their ethnic wardrobe and carrying spears, as security guards.

Case Study: Fatuma Ramadhani

The account of Fatuma Ramadhani illustrates the dilemmas faced by labourers and others playing a supporting role in the local economy. She was born and raised in Morogoro District. Married in 1972, she went with her husband to Manzese, which at the time was one of Dar es Salaam's outermost districts. She engaged in a variety of small businesses, including marketing corn grown by her relatives in Morogoro and selling home-brewed alcoholic beverages. She divorced her husband in 1978 and returned to Morogoro, where she met her second husband. She once again moved to Dar es Salaam – only this time, her new husband worked as a hired hand for an urban farmer living in Kilongawima. She referred to her husband's employer, a Chaga man living up the hill, as their tajiri, meaning rich person or patron. She continued engaging in small enterprises, including running a wholesale cloth business: she bought quantities of cloth and divided it among groups of machinga, or petty traders, who carried it around to neighbouring houses to sell.

Between her husband's wages and the profits from her businesses, they were able to muster enough money to purchase a small plot from her husband's employer. In 1989, her second husband died, and with the loss of his contribution to the household she reorganized her economic plans. Since the plot was too small to make a viable farm, she built a somewhat large wattle and daub house with eight separate apartments and began renting rooms to those needing them. Her first renters were farm hands also working for her deceased husband's employer. But in 1998 their tajiri died and his widow discontinued the employment of many hands who had worked there. A fortunate few found work on other farms or businesses in the area. Two other renters began working for Fatuma's corn wholesale business in exchange for room and board.

More recently, urban farmers expressed a preference for house girls or male farm hands from their home regions. Many claimed to prefer rural labourers with recent farming or herding experience over established urban labourers. Others suggested that urban youths are uncouth and therefore unreliable workers. One somewhat cynically explained that hiring fresh rural workers is preferred because it is easier to obtain pliant workers at low wages who are less likely to leave for another proprietor's farm. Some labourers, such as women who seek employment as house girls, live within the household; their job entails watching children and assisting in the daily upkeep of the farm. They often receive paltry wages but live with the family, thus gaining room and board.

Environmental concessions and inputs to urban farms

The Dar es Salaam Region is dry, tropical coastal savannah, with irregular fertility. While members of the suburban vanguard made concessions to the coastal savannah in order to make their farmsteads viable, they also attempted to overcome these limitations through the intensive input of resources into the land – fertilizer, piped water, and other resources available in a region close to a major city. Modelling familiar practices from rural regions of origin, householders commonly collected grass from unoccupied neighbouring plots to feed animals and mulch plants. Offal from local fish markets could be fed to pigs or added to a banana grove as fertilizer. Chaff, discarded from local commercial flour mills, served as supplementary cattle, pig and chicken feed. In addition to these outside sources, household waste from family meals contributed feed and fertilizer. Through the 1990s, such inputs were plentiful in nearby markets and roadside settlements, or on adjacent unused land around farms. Increasingly, however, as neighbourhoods have become more densely settled, and demand for chaff and other waste has increased, farmers have had to drive further afield to obtain these inputs. Faced by the difficulty of obtaining a steady supply of feed, and dropping milk prices, many holders of dairy cattle have considered abandoning animal husbandry.

Water was and continues to be a challenge for urban farmers. In this region, maintaining banana groves require ample water. Initially, farmers depended on local shallow wells, which are less frequently used these days because of their high salinity and vulnerability to contamination. By the late 1990s, farmers utilized water piped in by DAWASA (Dar Water and Sewage Administration) from the Ruvu River, a permanent major river that passes about sixty kilometres west of Dar es Salaam. DAWASA had water mains along major arterial roads around Dar es Salaam, and urban farmers could pay a quarterly fee to receive water from the company. Householders are also responsible for supplying and running their own hoses to their farms.7

HOUSEHOLD ORGANIZATION

Data from the 2002 Tanzania national census indicate that average household size in Dar es Salaam, whether in rural or urban areas, has been shrinking over the last twenty years. In the urban areas of Kinondoni, the average household size is 4.2 persons per household, down from 4.5 persons per household reported in the 1988 census (United Republic of Tanzania 2004: 92). Urban farm households reflect this overall trend, and commonly include the husband and wife, unmarried children, and occasionally a resident house girl or herder, who may or may not be related.Footnote 8 Rural family members sometimes stayed in the household to conduct business or seek educational opportunities in the city. But such visitors tended to stay only briefly, preferring whenever possible to find accommodation closer to the central city.

One possible explanation for the vanguard's tendency toward smaller households may be the kinds of provisioning required while living closer to the central city in the 1960s and 1970s. Not unlike their husbands, women were engaged in the professional sector of post-colonial Dar es Salaam. However, they tended to spend a greater amount of time living in and maintaining the rented flats built by the parastatal National Housing Corporation (Lewinson Reference Lewinson2006: 475–8). Unlike earlier ‘Swahili’-style urban houses characteristic of the colonial era, the parastatal housing utilized by urban professionals was constructed to suit nuclear families with few children rather than the more extended family groupings common to many ethnic groups of Tanzania.

Although such professionals lived side by side with less substantively employed urban residents, this group was distinguished by its distinctive patterns of work, consumption, and social interactions within this urban setting. The new parastatal urban housing gave rise to a form of urban domesticity markedly different from the more ‘Swahilized’ style of urban life that had characterized Dar es Salaam during the colonial period (Lewinson Reference Lewinson2006: 480). As the vanguard moved to peri-urban areas, many built gradually, starting with a shed or two-roomed house, sufficient for sleeping and cooking. Gradually, they added rooms to complete the house. Other householders in Kilongawima and Kwa Kisuguli hired VETA-trained builders, who received vocational training in designing and constructing ‘Sinza-style’ five-room houses using pressed blocks.Footnote 9 These houses comfortably accommodated nuclear families, and may have contributed to the trend toward smaller household size documented in the census.

Reflecting this overall trend, household activities of the urban vanguard were ensconced in urban culture. Though women continue to follow the tradition of preparing meals, increasingly families eat together during morning tea and the evening meal. Women whose families can afford a car often drive to and from work. Men increasingly take responsibility for daily activities within the household like assisting children with homework and storing food. Often, one of the top priorities for money generated through selling produce and animal husbandry is the payment of school fees. And women often have a wide-ranging network of kin and associates that live in the city, making visits and receiving guests a daily part of the urban routine.

A growing trend in these suburban districts is women-headed urban farms, mirroring the fact that within Kinondoni District fully 30 per cent of private households are headed by women (United Republic of Tanzania 2004: 93).Footnote 10 Maria Swai moved to Kwa Kisuguli with her husband in the early 1980s. Her husband died about ten years before I arrived, and she continued to live in and run the household. The only notable difference was that she does not own as many cattle as the family had when the husband was still alive. Another woman ran a large farm with the assistance of recruited labourers. Her husband and sons, she explained, agreed that she would live on the farm. They were content to remain within central Dar es Salaam, where her husband works, and where they own another house.

CAPITALIST REFORM AND THE NEW EMERGING ELITE

By the late 1980s, the Tanzanian government had begun to recognize the internal contradictions inherent within the strict rules of the Arusha Declaration limiting land ownership and private enterprises. With Julius Nyerere's retirement from the presidency in late 1984, there commenced a withering away of the socialist project, and the government increasingly tolerated urbanites engaging in petty capitalist ventures. Both internal pressure, exerted by citizens engaging in such activities, and external pressures from the IMF and donor countries compelled the government to create a new economic and political agenda through the Zanzibar Declaration of 1991 (Tripp Reference Tripp1997: 185–9). Industries nationalized following the Arusha Declaration were privatized, and restrictions were lifted on capitalist ventures.

One of the results of this new liberalization was nearly two decades of continuous growth in the Tanzanian economy. Through the 1990s, GDP growth averaged 3.5 per cent (ICON 2000). By 2005, GDP growth had reached 6.7 per cent, with no signs of abating (Brennan and Burton Reference Brennan, Brennan, Burton and Lawi2007: 65). The most obvious beneficiaries of this unprecedented growth of Tanzania's economy were its emerging transnational business and political elite, many of whom were centred in Dar es Salaam. As capitalism became the accepted norm following the Zanzibar Declaration in 1991, and as the Tanzanian shilling became subject to inflation during the decade of the 1990s, this emerging elite began to view peri-urban areas as a place to invest its new-found wealth (Briggs and Mwafupe Reference Briggs and Mwafupe2000). Throughout the 1990s, they put their wealth into houses, farms and land on the outskirts of Dar es Salaam.

Though similar to the vanguard in background and education, this urbanized group was far less willing to give up urban services and amenities in order to live on remote urban farms on Dar es Salaam's fringe. A few initially relocated in the far northern and western fringes of Dar es Salaam District – not necessarily to farm, but to take advantage of job and investment opportunities at nearby employment centres such as the Wazo concrete factory and tourist hotels. But living on a farm without the benefit of running water, telephone, electricity, shopping or ready access to transportation was not viewed as desirable.

As the vanguard's productive activities increased, they managed to build their own infrastructure, bringing water, electricity, telephone and local bus services to their settlements. As this infrastructure improved, and the government built or repaired feeder roads, more and more residents of inner Dar es Salaam ceased thinking of the suburbs as isolated outlying regions, and contemplated acquiring land and building themselves. From the perspective of residents who have moved since the late 1990s, outer suburbs offered a less crowded, less hurried and more modestly priced location. With an obviously strained but growing infrastructure, moving to these more distant areas of the city now meant that one could live there without severing connections to jobs, businesses, friends and relatives in the inner districts of Dar es Salaam. Rather than sell their old homes, if they actually owned them in the inner districts, many rented these houses to other urbanites living closer to the central city. The more successful individuals often control several pieces of land beyond the one on which they happen to live. Property in the inner suburbs might be used as rental property, the farm meets the immediate needs of the family, and there has been a tendency for individuals to own plots outside the city limits – some as far away as Kibaha and Bunju, 30 or more kilometres from City Centre, for cattle keeping and agricultural activities requiring still larger spaces.

Members of the urban vanguard were advantageously situated when changes occurred following the Zanzibar Declaration. With the privatization of parastatal industries and drastic reductions in civil service employment, most employees were offered generous severance packages for voluntary retirement. Many retired civil servants used these severances to acquire land, and somewhat belatedly joined the vanguard. Members of the vanguard, already controlling land, could use these packages to expand their farms or diversify their household activities. Their households and farms compare favourably with those of the more recent member of the new transnational elite.

On the other hand, many of those who began as part of the initial vanguard feel squeezed by the presence of so many neighbours. They complain that it is becoming harder to find grazing land and grass for their animals, and that with an increase in the number of people there has been an increase in the amount of theft and clashes with neighbours. They suggest that the processes by which areas closer to Dar es Salaam, like the districts of Sinza and Mwenge, became inner suburbs is happening in Kwa Kisuguli and Kunduchi, and that a visitor coming in five years or so probably would be unable to distinguish Kilongawima or Kwa Kisuguli from other densely packed residential areas of the inner city.

CONCLUSION

This article interrogates the classical model of African urban adaptation theory, using the example of the growth of the peri-urban districts of Dar es Salaam in the last twenty years. The anthropologist Anthony Leeds (1994: 71) pointed out that ‘any society which has in it what we commonly call “towns” or “cities” is in all aspects an “urban” society, including its agricultural and extractive domains’. Urbanization is an elaboration of that social division of labour in complex society, based on the ‘internal differentiation of the function of localities’ (1994: 53), rather than a domain separate and distinct from the rural hinterland that supports it. Peri-urban farming was initiated by a vanguard of educated urban professionals as part of a strategy of economic diversification following economic crises in the 1970s and 1980s. Participants drew upon a repertoire of relations of production, suggestive of both urban and rural antecedents. Initially seeking economic diversification, the vanguard brought urban inputs and initiated infrastructural changes that turned out, in the end, to serve them well in maintaining and furthering positions of economic dominance relative to other urbanites.

The trends documented in this study give rise to a number of intriguing follow-up questions about the nature of urban farming in Dar es Salaam. First, to what degree is the virtual culture documented in this study a kind of memory culture, specific to the ethnic groups who attempted to recreate urban gardens suggestive of their natal homesteads? In the course of numerous interviews, residents sometimes juxtaposed descriptions of their urban farms and households with recollections of their lives before arriving in Dar es Salaam. Others commonly compared and contrasted their practices with those of other ethnic groups, especially the Zaramo and representatives of other ethnic groups who preceded them. However, no one ever explicitly stated that he or she farmed ‘like a Chaga’ or ‘like a Nyakyusa’. They often viewed their activities as best practices within their current situation, evidently contributing to success in weathering past crises, and prospering in relation to other groups.

It might also be worthwhile to inquire as to whether these new social forms will persist, and if so, what forms they might take in the future. It is possible that cultivable land may not remain as critical a component in shaping common interest communities; or that there may be a consolidation of landed interests; or an eventual replacement of the current resident families with new ones, each with its own social configuration and strategies for furthering socio-economic interests. Or, perhaps, farmers might adopt mixed practices characteristic of a range of ethnic groups, and together with inputs available in the urban market, create a ‘substratum’ for farming distinctive to the urban environment. A worthwhile avenue for future research might involve a follow-up study to examine the extent to which the younger generation continues similar patterns of settlement, or abandons them in favour of other kinds of urban social formations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A number of individuals and institutions made this study possible. First, I would like to thank the government of the United Republic of Tanzania for granting clearance for field research conducted in 1998 and 1999. This research was also made possible by a Fulbright-Hays doctoral dissertation grant. Many thanks to the anonymous reviewers of Africa, Sara S. Berry, Chigon Kim, Marlese Durr and Jim Brennan for their thoughtful and insightful suggestions. Special thanks to Stefan Dongus, who gave permission for the use of maps of peri-urban Dar es Salaam. I would also like to thank Mr Charles Kawishe, Prosper Mambo, Alan Nyange, Anton Ishengoma and the many government officials who provided much assistance during my fieldwork in Tanzania in 1998 and 1999.

Figure 1 Dar es Salaam, showing major urban and peri-urban wards, 1999 (adapted from ‘Regional Map of Dar es Salaam’, Survey and Mapping Divisions, United Republic of Tanzania, 1995)

Figure 2 Dar es Salaam, showing urban and peri-urban farming areas in 1998–9 (Source: Dar es Salaam City Commission, Sustainable Dar es Salaam Project for Urban Vegetable Promotion Project, 1999)

Figure 3 Northern Kinondoni, showing major non-residential uses of the area