Nomenclature

- m2

-

square meter of area

- lbf/ft2

-

Pound Force Per Square Foot on wing

- N/m2

-

Newtons/Square Meter (weight to surface ratio)

- hp

-

horse power of power plant

- N/m

-

Newton-metre

- cc

-

cubic capacity of transport engine

- Wh/m2

-

watt per square meter is radiative fluxes in geophysics

- Nm

-

Nautical mile

- Kg

-

Kilogram

1.0 Introduction

Emerging economies are defined as those that are in the process of becoming developed economies [Reference Mody1]. According to Haque, emerging economies in the next wave include the United Arab Emirates, Chile, Malaysia, Vietnam, Philippines and Bangladesh [Reference Haque2]. We choose Bangladesh to obtain raw data because this is one of the promising economies on the edge of joining an emerging market with several challenges, ranging from policy, poverty, Gross Domestic Product (GDP), life expectancy, social security and climate.

On November 6, 2018, the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) hosted a workshop on “Transportation in Emerging Economies.” The Chatham House Rule event convened representatives from government, international organisations, think-tanks, academia and private businesses. There were five main takeaways [Reference Tsafos3] from that wide-ranging conversation. The major point derived was that, as population grows, demand for urbanisation and transportation grows exponentially. By 2030, we will have 43 megacities with more than 10 million inhabitants [4], which will significantly increase demand for transportation. There is no single pattern for urban development, energy and transport if one compares Africa, Latin America and Asia [Reference Tsafos3]. Their transportation services will thus require a holistic approach, considering factors such as the urban environment, cost, safety, population density and sustainability [Reference Tsafos3]. There is a significant drive towards electrification in the transport sector by using renewable energy, which creates many opportunities and challenges [Reference Tsafos3]. In conclusion, the study by CSIS agreed on a holistic policy that is required to shape the future of transport, where consumer demand is met by innovative and pragmatic solutions. Part of such an innovative solution would be the use of different modes of transport, amongst which General Aviation (GA) aircraft appear to be lacking in terms of recognition and utilisation, specifically in emerging economies such as Bangladesh, which is a river-based country with a high population index.

Moreover, this study based on emerging economies leads to several research tools for obtaining data and analysing them to come up with a final implementation. The commercial success of a product depends on the degree to which it fulfils user’s needs and creates a need in the consumer. Fulfilling user needs by designing a purposeful solution requires a group of (technical and non-technical) personnel working hard in relation to the different stakeholders of a particular project. Generally, product development starts with requirements engineering, of which requirements elicitation is a fundamental part. Requirements are not readily available but must be elicited and adjusted as per the needs of the design, because come from customers, who are not as organised as designer, hence the designer cannot start designing immediately at the start of a project.

To illustrate this dilemma, in 1796, Joseph de Maistre highlighted in his Considérations sur la France that “it is much less difficult to solve a problem than to define it”, where requirements play the main role when identifying the real scope of the problem [Reference Micouin and Pomerol5]. In the context of aircraft design, it is challenging to come up with a set of specific requirements that could fit the design goals, since a good number of variables influence the design decisions in different directions. Although the future is uncertain, the race is on to consciously predict customer needs.

This study concluded that almost all current GA aircraft in production are designed for use in developed countries with the following roles in mind: training, touring and recreational use. Some such aircraft have been pressed into different roles in emerging economies, albeit with a sacrifice in terms of performance or efficiency. In terms of aircraft shape, material and manufacturing techniques, the changes seen since the 1950s have not been as drastic as in other industries such as the automotive industry, which is subject to continuous change to accommodate its wide range of user needs as well as to maintain its position as an industrial leader. Whereas the aviation industry has not paralleled the automotive industry, some excellent developments including the morphing wing, blended wing body, etc., have been achieved, although still in the research incubator stage with potential commercial applications under development.

Burt Rutan, one of the leading innovators and enigmatic aircraft designers of the 21st century, highlighted that he “thought there would-be competition that would drive costs down to an absolute minimum and push speed to the technological maximum”. He also claimed to be “just shocked that somebody didn’t take the research that had already been done and build a modern general aviation aeroplane” [6]. We thus believe GA is the correct platform to introduce something new, innovative and efficient to the world. As soon as mass production starts, the cost of such aircraft will decrease, but of course, legislative constraints should be adjusted in relation to such changes.

It is important to note that there is no precise and universally accepted definition of general aviation, and indeed the generic name GA remains imprecise [7]. Such aircraft require certification, although small aircraft with a single engine (with a maximum take-off weight of 5,670kg) according to CS 23 are considered to be GA aircraft for the sake of this work. The CS 23 is the certification standard set by the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and by the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) of the USA, setting out aircraft performance and safety factors. Hence, any design specification originating from customer requirements must comply with such CS 23 regulations. The main purpose of aviation regulation is to ensure passenger and public safety.

The remainder of this manuscript is organised as follows: In Section 2, we survey different requirements elicitation methods/processes, identifying three viewpoints that serve our research needs. In Section 3, we propose a requirements elicitation process based on the viewpoints determined in Section 2, as we did not find a relevant process similar to that targeted herein. Based on the proposed process, we collect large amounts of information targeting the emerging economy context. In Section 4, we demonstrate the raw requirements and analyse their feasibility in terms of engineering applications by using the Quality Function Deployment (QFD) approach. To visualise the functional scenarios of the system (GA aircraft) in relation to users, a SysML use-case diagram is formulated. Some raw requirements are then verified through constraint analysis and cost examination to present an exemplary approach demonstrating the transformation from raw to final requirements, which is the main goal of requirements engineering in the systems engineering domain. Section 5 examines all our claims and the limitations of this work. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and provides a brief outlook.

2.0 Literature survey

This section discusses several methods that are commonly adopted when performing Requirements Engineering (RE). If we consider the left-hand side of the Systems Engineering (SE) ‘V’ life cycle model, RE represents the first step of the process; for instance, the ISO 15,288 standard also describes RE (not explicitly requirements elicitation) as part of the life cycle process [8]. Requirements elicitation is one of the first parts of RE, and other parts such as analysis, specification and validation [Reference Marcelino-Jesus, Sarraipa, Agostinho and Jardim-Goncalves9] are developed based on it. According to Hooks, a good requirement should define the needs, attainability, clarity and verifiability [Reference Hooks10]. The goal of the current paper is thus to achieve all of the above-mentioned conditions to formulate good requirements for the target market.

Before jumping into the requirements elicitation process, it is essential to know which types of requirements we will focus on. According to Novorita and Grube [Reference Novorita and Grube11], requirements can be classified into: (i) user requirements, (ii) business requirements and (iii) systems requirements. User requirements are obtained from end-users and customers of the system, thus representing the market needs, which are not stable [Reference Novorita and Grube11]. Business requirements are a formal instrument to help to refine the enterprise requirements and corporate partnerships in parallel with the product requirements [Reference Novorita and Grube11]. System requirements fulfil volatile user/market requirements by establishing key attributes, which requires technical guidance [Reference Novorita and Grube11]. The current unique research approach and product avoids the omission of any useful requirements that are relevant to the specific market. The approach and product are unique in the sense that GA aircraft are usually designed to target developed countries and wealthy individuals. In contrast, our target demography and socio-economical context are different from these usual norms.

According to Marcelino (2014), the requirements elicitation stage includes three steps: understanding the project, brainstorming based on scenarios and accumulating raw requirements [Reference Marcelino-Jesus, Sarraipa, Agostinho and Jardim-Goncalves9]. Boota (2014) proposed four steps for requirements elicitation: defining product technical environment, eliciting through interviews (questionnaires and team meeting etc.,) to engage experienced people and understand their opinion, recording elicited requirements and creating a use-case diagram based on the study review [Reference Boota, Ahmad and Masoom12].

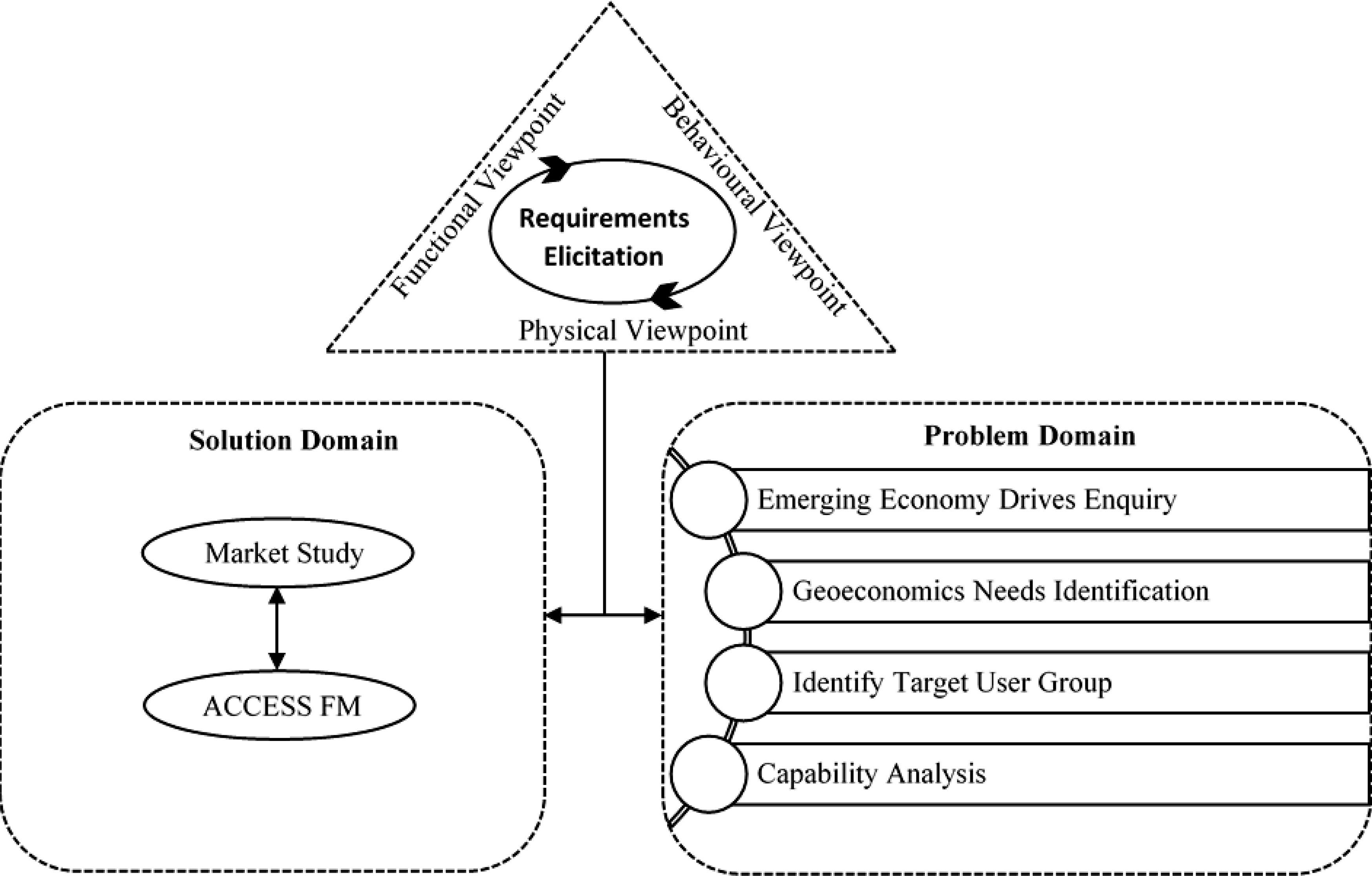

Nevertheless, requirements elicitation can be carried out by following various methods, namely goal-oriented [Reference Adikara, Hendradjaya and Sitohang13], data-driven [Reference Adikara, Hendradjaya and Sitohang13], ontology-based reasoning [Reference Dzung and Ohnishi14], model-driven prototyping-based [Reference Fu, Bastani, Yen, Paech and Martell15], scenario-based requirements elicitation [Reference Haumer, Heymans and Pohl16, Reference Watahiki and Saeki17], etc. Unfortunately, none of these is an accurate fit to unique problem. We thus used existing requirements elicitation knowledge to propose a new process (Fig. 1) that matches particularly well with our specific market, users and product. Note that it may or may not be applicable to other circumstances. This approach focuses on the functional, behavioural and physical viewpoints of the GA aircraft. Here, ‘function’ defines the action of the system, ‘behaviour’ how it performs its functions while ‘physical’ defines the effects of the combination of ‘function’ and ‘behaviour’ on the physical structure of the target system (i.e., a specific GA aircraft) (Fig. 1). This approach helps us to address several unforeseen problems associated with requirements elicitation in this scenario and unpack many deeper features, while also avoiding more time-consuming methods such as stakeholder interviews with questionnaires, focus-group interviews, requirements workshops and surveys. In addition, it is difficult to find specific end-users or customers who might have an overview of the whole scenario and use-cases of emerging economies in relation to GA aircraft. The approach proposed herein (Fig. 1) could thus mitigate all these kinds of stumbling block.

Figure 1. Requirements elicitation process.

3.0 Methodology

Requirements elicitation starts with an elicitation activity, which identifies the purposes of the system under development; this stage determines what to build, why to build it and where to build a particular system [Reference Ramingwong18]. Indeed, the prime goal of requirements elicitation is to gather raw requirements [Reference Farfeleder, Moser, Krall, Stålhane, Omoronyia and Zojer19]. As requirements elicitation depending on the market needs of emerging economies is our main concern herein, we propose the process illustrated in Fig. 1 to help understand, execute and evaluate useful raw requirements for GA aircraft design. To improve this analysis, the requirements elicitation process is divided into two parts, corresponding to the ‘problem domain’ and the ‘solution domain’. The problem domain determines the ‘what’ while the solution domain identifies the ‘how’ of the requirements elicitation process. The Methods part of this paper is exclusively dedicated to explaining this requirements elicitation process in detail.

In the proposed approach, requirements are elicited based on the functional, behavioural and physical viewpoints, as defined in the literature survey described above. These three viewpoints help to reveal the scenarios of the target system, realised using a market study. However, the large amount of information yielded by a market study must be fine-tuned with a specific boundary to make it measurable for the selection of raw requirements; this boundary can be drawn by using the Aesthetic, Cost, Customer, Environment, Size, Safety, Function, Material, Manufacturing (ACCESS FM) tool [Reference Hassan Shetol, Moklesur Rahman, Sarder, Ismail Hossain and Kabir Riday20]. Moreover, this tool enables one to fashion many research questions that will help to perform the market research in a controlled fashion, and these questions will be a useful basis for the investigation during the conceptual development phase for the system and subsystems as part of the architecture strategy. The problem domain expresses the problem using the assigned attributes to help with the market research activities, and the market research is combined with the ACCESS FM approach to construct measurable requirements. In general, the three sections of Fig. 1 operate in a regulated, collaborative mode to yield purposeful raw requirements, which will then induce a purposeful GA aircraft design, the main goal of this study. One of the known frameworks for requirements engineering is the Performance, Information, Economics, Control, Efficiency and Services (PIECES) framework [Reference Febriani and Dewobroto21]. This framework provides an excellent outline of problem areas by exploiting problem categories rather than solving them. Therefore, in the proposed process, especially in the problem domain (Fig. 1), we have used some of the attributes of the PIECES framework to identfiy and classify problems, viz. economy, performance and service [Reference Febriani and Dewobroto21].

All the attributes in the solution domain in Fig. 1 do not explicitly function as solutions but rather help to derive solutions and make better decisions. The problem and solution domains are thus inter-reliant. To solicit the attributes related to the problem domain, the next part of the study is initiated in a systematic way with the help of the solution domain attributes, which are broadly discussed below.

3.1 Market study

To design the extrinsic and intrinsic goals of a product, the user needs must be known implicitly [Reference Zeman, Azad, Scheidl, Jungreitmayr, Khandoker, Wahl, Buchegger, Haas, Hoffelner, Boschert, Rosen, Aschpurwis and Wanner22]. To achieve this, a market study should obviously be carried out before starting the product design process. However, particularly for this research, it is essential to identify the relevant requirements that could fit with emerging economies. Aircraft are not a usual mode of transport in developing countries, and potential users may not be aware of it. In addition, it is hard to assess who the end-user is. Therefore, to trace the requirements of every single user in different layers of the socioeconomic system, a navigating approach is essential. Meanwhile, a market study helps to gather data in an organised fashion with the aim of helping to extrapolate the analysis boundary to interpolate fine-tuned decisions rather than an academic guesstimate. Carrying out a market study also helps to reduce risk by providing better understanding of customers and market situations. However, it will identify not only ‘what’ the problems are but also ‘why’ they are problems. As soon as this ‘why’ is known to the product development team, development a productive solution might become comparatively less challenging. We thus perform a market study based on the problem domain constituents, which are presented broadly in the next part of this paper.

3.1.1 Emerging economy drivers

With the rapid changes in the global economy, emerging economies have been placed in the driving seat due to their significant contribution to the world economy. Between 2008 and 2013, emerging economics contributed approximately 80% to the growth of the world economy [Reference Marina23], whereas during that time frame, an economic recession took place. On the one hand, emerging economies have great potential in terms of growth and diversification in most business sectors; on the other hand, many risk factors could block their potential. In most cases, the risk factors are political instability, internal policy changes, high inflation or deflation, unregulated markets, currency devaluation, etc. Therefore, the current paper evaluates the challenges and opportunities of emerging markets in regard to setting up a GA aircraft manufacturing industry through requirements elicitation to facilitate design decisions.

Globalisation has added a new dimension to social life, driving various communication media to develop to the next phase, and this momentum has influenced the economy, causing it to change similarly. Against this background, both emerging and developed economies have prospects to exploit the related benefits of this changing economy. Therefore, there is a comparatively lucrative opportunity for entrepreneurs to enter emerging markets to obtain high gains. However, understanding the culture and priorities of customers’ burning needs within this field is of prime importance when a new company starts to include emerging markets in their upcoming business endeavours. Similarly, we analyse herein the needs related to aviation transport and the specific geo-economic cultures related to communication systems, which can be found in a later section of this paper.

3.1.2 Geoeconomics must be identified

To identify geoeconomic needs, the specific demography must first be considered. According to the Economics and Monetary Union, Bangladesh is a country with an emerging economy [Reference Ciravegna, Fitzgerald and Kundu24], offering stable economic conditions over the last decade with GDP growth above 6%. Moreover, according to the World Bank, in the year 2019, the GDP growth rate was 8.2% [25]. For this reason, we consider Bangladesh as our target research territory, and due to our field knowledge obtained over a period of time in the aviation sector in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh is a South Asian country with an area of 147,570km2 [26]. It has a subtropical monsoon climate characterised by wide seasonal variations in rainfall, high temperatures and humidity. There are three distinct seasons in Bangladesh: a hot, humid summer from March to June; a cool, rainy monsoon season from June to October; and a cool, dry winter from October to March [27]. It is also known as a riverine country because of the numerous rivers flowing through it. Therefore, regarding the transportation system, waterways have always played a significant role in the country. Other modes of transportations are roads, rail and air, as described in the following sections.

Transport is one of the important catalysts to stimulate any country’s economic growth, and this also applies to Bangladesh. Since the liberation of the country, the development of infrastructure has progressed rapidly, and a number of new land, water and air transport modes came into existence. Among the various modes of transport, the road transport system has played a significant role in transporting passengers and goods. Currently, the Roads and Highways Department (RHD) manages approximately 20,948km of roads, 4,659 bridges and 6,122 culverts [28]. In the last decade, the Local Government Engineering Department (LGED) has constructed a total of 150,677 roads with a total length of 133,514km (comprising approximately 64,691km of dirt roads and 68,823km of paved roads) [28]. Apart from fast movement of goods and passenger traffic, roads and bridges also facilitate the transmission of electricity and natural gas and have integrated telecommunication links [28]. Moreover, several massive road development activities are underway in both urban and rural areas to accommodate the sharp increase in the number of vehicles. However, traffic congestion and fatalities due to road accidents are common phenomena on most urban roads. The cost of public transport by road is continuously multiplying. Additionally, one of the dream projects of the country, Padma Bridge, is under construction and is planned to open for traffic in mid-2021. When commissioned (2014), it was expected to boost the GDP of Bangladesh by as much as 1.2% [29]. However, the current overall picture of road transportation reveals an inadequate supply against vast demand.

Regarding water transportation, according to the World Bank, in 2016, the inland water network of approximately 3,900km remained the only mode of transport for 12% of rural communities in the country, supporting the transport of around 194 million tons of cargo and representing approximately 25% of the traffic load in the country per year [30]. Locally made watercraft such as Sampan, Balam, Teddy, Bajra, Jali, etc. are the most widely used on waterways to carry large numbers of passengers and cargo. Other large-sized watercraft such as launches and ferries provide transport services to several major cities (Dhaka, Chandpur, Ashuganj, Barisal, Narayanganj, Khulna, etc.) for carrying passengers and goods. According to the Bangladesh Economic Board Authority, approximately 250 major rivers in the country are used as major transportation systems [26]. Chittagong, Mongla and Payra Ports are considered to be the major seaports in Bangladesh, although the Sonadia small seaport and Matarbari deep seaport are also under construction [Reference Islam31]. In addition, there are around 15 major river ports operating in Bangladesh [Reference Islam32]. However, due to mismanagement and health and safety risks, overcrowding and long journey times make the inland water transportation system unpopular, although the cost of such transportation is very cheap compared with other modes of transport.

Like waterways and roads, trains also play a vital role in the Bangladeshi transportation system, using a network with a total length of 2,853.04km [26]. There are around 489 stations, which cover most of the major cities in the country [26]. About 32% of the total area of Bangladesh is reached by the rail network [26]. Several new train lines are under development to service new destinations. Due to its cheap ticket prices, this is a popular transportation medium for people in the country. However, the quality of the service offered has not been improved significantly. Schedule delays and train ticket fraud marketing are common on the Bangladeshi railway system, thus train travel has still not become a reliable transport system in Bangladesh. However, one glimmer of hope is that, in parallel to the massive digitalisation activities underway throughout the country, Bangladesh Railway is also trying to modernise, which is starting to be reflected in a substantial change in the rail transport ticketing and information management systems. Notwithstanding, the overall effect of this change will take some time to appear and have a real impact.

Air transportation is one of the least popular transportation systems in Bangladesh. The Bangladesh Civil Aviation Authority (CAAB) maintains, supervises and controls all the airports and aviation-related rules and regulations in the country. According to CAAB data, the combined annual market size of 2014 was worth USD 440 million, with 5.8 million passengers and 230,000tons of cargo [Reference Sultana33]. There are three international, five domestic and five Short Take-Off and Landing (STOL) airports in operation, albeit with no scheduled flights available at the latter.

One new domestic airport named Bagerhat Airport is also under construction [34]. The national carrier, Biman Bangladesh Airlines, flies to around eight domestic destinations. Other commercial airlines including US-Bangla Airlines, Regent Airways and Novoair offer flights between different domestic airports. Detailed information from all the airlines is presented in Table 1. Some companies also provide helicopter and GA aircraft services, with an hourly charge. Details of these alongside other necessary information are presented in Table 3. Although it is well known that travelling can save time, it costs far more than the popular modes of transport. One major disadvantage of the existing air transportation system in Bangladesh is its limited destinations. For example, a passenger wishing to travel from Dhaka to Rangpur must first fly to Rajshahi, then travel to Rangpur by road, which adds extra hours to the journey as well as extra cost to the traveller. Passengers may also face difficulties during travel (Table 2). This is therefore one of the main reasons why air transportation is not very popular in Bangladesh due to the airports and cities are not co-located (Fig. 2).

Therefore, based on the above discussion, it is observed that there are many modes of transportation in the territory, but their availability is limited compared with the exponential demand. However, of course, there are new additions to the existing transportation system. The government expects that, by 2025, this imbalance between supply of and demand for mass transportation infrastructure will be eliminated.

3.1.3 Identify the target user group

The economic prosperity of a country relies heavily on the transportation systems developed in its socio-economic context. Meanwhile, economic activities cannot be accelerated without proper infrastructure. Most service-oriented functions in the economy are dependent on the transportation system, which relies on the infrastructure that is available. Therefore, the development of infrastructure and of the transportation system are two sides of the same coin. Moreover, one cannot be established without the other. However, infrastructure development is time-consuming and takes a long time to plan. According to the local newspaper The Daily Star, various mega-projects are under construction in Bangladesh, including Karnaphuli Tunnel (an underwater tunnel), the Dhaka Metro Rail Project, the Payra Deep Sea Port and many more, which will take a few years to open for traffic [38]. However, a certain group of customers will still not use this category of transportation due to their different needs [28]. GA aircraft would thus be a suitable fit for a certain group of customers in this territory, offering a fast, safe but slightly expensive option. The question that then arises is who this group of customers would be. On the one hand, regarding into account, we performed a field survey via general discussion with aviation personnel and potential users. Meanwhile, an intensive literature survey was conducted to understand the socio-economic activities of the territory. Based on the results, the following use cases were identified as explained below:

Table 1. Domestic flight frequency at different airports in Bangladesh (Flightradar24, Reference Farfeleder, Moser, Krall, Stålhane, Omoronyia and Zojern.d.) (Source: based on our field survey)

1Passenger capacity depends on aircraft type currently operated (January 2020)

Table 2. Journey time comparison by different modes of transportation (Source: based on our field survey)

ICtg. = Chittagong.

IICommon traffic conditions.

IIIWithout considering weather or signal failure.

IVBest road traffic condition and airport check-in and check-out time (add 2:30 h.)

VHSIA = Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport.

Table 3. Different GA aircraft users in Bangladesh (Source: CAAB aircraft operators BD based on our field survey)

a. Personal/executive/leisure transport

According to the World Bank, the Ready Made Garments (RMG) sector makes the largest contribution to the country’s exports [39, Reference Yunus and Yamagata40]. However, the agriculture and pharmaceuticals sectors also make an important contribution [39, Reference Yunus and Yamagata40]. Moreover, tobacco, printing and publication as well as re-rolling sectors help to accelerate the overall economy of Bangladesh [Reference Yunus and Yamagata40]. In some cases, factories operating in those industries are located in remote parts of the country, while the headquarters is situated in the capital or other megacities such as Chittagong, Khulna, Sylhet, etc. Meanwhile, most foreign investment companies are located in the specialised Export Processing Zones (EPZs), which are also typically situated in remote areas [Reference Yunus and Yamagata40].

Therefore, it is often the case that executives/higher officials working in these industries must visit factories via scheduled flights to nearby cities. As mentioned above, due to the lack of flights and destinations, such journeys by business executives suffer from considerable turmoil. However, considering this problem to be a business opportunity, Youngone Corporation Bangladesh has started an aviation business called Arirang Aviation to support their RMG business transportation needs. This aviation platform provides charter, air ambulance and flying school services, and this company is a success story, as demonstrated by its successful track record over more than 17 years in the Bangladeshi aviation industry. Following in its footsteps, various other companies (Table 3) have also started aviation business based on different aircraft/helicopters extensions of their mainstream business. However, they have yet to build notable businesses. This can be attributed to the fact that most of them have limited their services to helicopters.

To understand the current situation on the ground regarding costs and journey times from major cities to the capital Dhaka, a comprehensive study was first carried, considering different modes of transport and travel times (Table 2), thus demonstrating unsurprisingly that the actual journey time by air is quickest. However, all the airports are located outside of the city, while the commercial hub lies at the heart of the city, where there is no point-to-point option with direct links and airport formalities (check-in, security, baggage collection and check-out). Current commercial flights take two-thirds of the road journey time, with the additional stress due to airport formalities, reliability issues and high cost, whereas the use of GA aircraft for point-to-point travel would be faster, reliable and stress free. Overall, in the long term, this will also save money due to increasing efficiency.

According to the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA), there are around 4,500 RMG factories in Bangladesh [41]. Considering as little as 0.50% of these factories’ owners who can buy and maintain a GA aircraft, there is market demand for approximately 225 aircraft. Moreover, their price is supposed to be similar to that of a luxury car, roughly $120,000 to $1,000,000 (Table 4), based on intensive discussion and study of this question with potential customers. Thereupon, one can assume that a price range for a GA aircraft around $120,000 to $160,000 would be tempting to potential buyers and possible fractional ownership (see below)

Table 4. Common luxury car prices (Source: based on field survey)

Figure 2. International and domestic airports in Bangladesh [37].

Moreover, the manufacturing cost of such aircraft would be lower, as already demonstrated for other transport vehicles in developing countries, because of reduced labour costs and various tax relief advantages from the government to drive down unit prices.

b. Transport for tourism

Remote areas of countries with emerging economies could be potential tourism and business destinations. Generally, remote regions are isolated due to the lack of proper modes of transportation; for this reason, the considered country Bangladesh with an emerging economy is one of the least popular tourist destinations in the world, according to the World Bank [Reference Haines42]. However, it is a beautiful country in South Asia bordering India and Myanmar. The main modes of transport in Bangladesh are by land and water. The air transportation system in Bangladesh is not very popular due to its high price and the low frequency of flights. Most tourist destinations in Bangladesh are remote and challenging to reach from the main cities (Dhaka, Chittagong, Khulna and Sylhet), so either tourists are afraid to go by usual transportation systems or do not want to experience the chaotic journey. Therefore, an air transportation system with small aircraft could open a new opportunity for tourism and cargo transportation by connecting such remote and isolated areas.

Some areas that are remote from the capital such as Saint Martin, Kuakata, Boga Lake, Cox’s Bazar and Sundarban are popular tourist destinations. However, the typical modes of transportation to these destinations are incredibly time consuming and difficult. The only route available from the main cities to these destinations (except Saint Martin and Sundarban) is by road and water. So, amphibious aircraft could be a means to boost tourism in the mentioned areas. Other fascinating tourist destinations such as Rangamati, Khagrachari, Bandarban, Sri-Mangal, Bagerhat and Barisal are also quite distant and troublesome to reach via usual modes of transport. Overall, to enhance the tourism sector in Bangladesh, GA aircraft could be an appropriate option with remarkable diversity. In other emerging economy countries such as the Philippines, “A thriving aviation industry is helping them to drive forward for a comprehensive tourism plan” [Reference News43]. This could be taken as a prime example to develop tourism in Bangladesh based on the tourism strategies applied in the Philippines.

c. Small cargo transport/airmail or fast courier service

There are many other financially stable companies in this field related to different industries that could afford such an aircraft, whose multipurpose uses are expected to support different business requirements. A common experience is that high-value but perishable items such as crabs, shrimps and various agricultural products are spoiled or devalued due to improper post-harvest supply chain systems. Pharmaceuticals is another promising industry sector that can be impacted by improper supply chain management in terms of raw materials and the supply of life-saving drugs. Most factories in this sector are located too far from export/import seaports. There is also good potential in the field of tourist travel using GA aircraft, as discussed in detail below. To attract the abovementioned different types of customer, the projected aircraft is supposed to be capable of both amphibious and multipurpose use, including cargo, air ambulance and executive travel, and this ability to accommodate so many different types of requirements is the most significant design challenge.

In Bangladesh, various businesses have developed in remote rural areas, including fisheries, garments, nuclear power plants, gas fields, etc. An analysis by Lightcastle Analytics Wing stated that “Bangladesh’s agricultural sector contributes 14.2% of GDP, employing 47% of the working population, with 17 million people (1.4 million women) depending on the fisheries sector for their livelihoods through fishing, farming, fish handling, and processing” [Reference Sultana44]. This analysis reveals the significant contribution made by fisheries. Most shrimp hatcheries are located at Cox’s Bazar, while shrimp cultivation areas are mainly at Bagerhat and Satkhira, so shrimp fry (tiny shrimp; caught by eye) must be transported from Cox’s Bazar to Jessore daily. To target this golden opportunity, cargo airlines including Bismillah Airlines dedicate aircraft to this route during the picking season. Unfortunately, it takes around 2h to reach the shrimp cultivation areas by land transport such as trucks. Hence, a good number of shrimp fry die due to transportation difficulties.

Small amphibious GA aircraft could thus facilitate this business by transporting baby shrimp to the exact location, i.e., Bagerhat, Satkhira from Cox’s Bazar, without requiring an airport. Fish farmers generally arrange transportation on a community basis, because a single fish farmer does not have sufficient capital to afford to transport shrimps alone. As a result, an individual fish farmer must wait for others to have enough shrimp fry to transport from Cox’s Bazar to the specific shrimp farming destination. This delay impacts on the fish farmer’s business model. Therefore, small amphibious GA aircraft would be the right fit with their (fish farmers) business requirements.

In another example, 90% of the supply of dry fish for export is dependent on Cox’s Bazar, Kuakata, Sundarban and Teknaf, but due to the lack of proper means of transportation, the supply chain management by the associated companies is complex. Moreover, the usual mode of transport decreases the quality of the product. However, by using GA aircraft, a proper supply chain and export timing could be maintained efficiently. Bangladesh produces 70–80% of the world’s supply of its national fish, the Hilsa [Reference Sultana44], which is in great demand for export. Therefore, transportation of Hilsa from all coastal and river areas to export locations could be eased by the use of GA aircraft. On the one hand, this could increase the export volume, and on the other, also decrease the substantial amount of wastage of this perishable good.

d. Remote mines or production facilities

In addition, “Natural gas played a vital role as one of the main energy sources to the rapid development of Bangladesh, production and consumption have increased drastically during the last decades” [Reference Hassan Shetol, Moklesur Rahman, Sarder, Ismail Hossain and Kabir Riday20]. A total of 27 gas fields have been discovered so far in Bangladesh, most of them located in remote areas [Reference Hassan Shetol, Moklesur Rahman, Sarder, Ismail Hossain and Kabir Riday20]. Due to communication obstacles, many scheduled maintenance tasks are delayed, resulting in reduced gas production and having a direct impact on the national economy. In the near future, the same effect may be seen at the Rooppur nuclear power plant, which is still under construction. Therefore, GA aircraft could provide a proper mode of transportation for maintaining schedules and have a positive impact on the national economy, which is one of the critical requirements to stabilise the emerging economic growth in Bangladesh.

e. General aviation (GA) airlines

Based on the results of our survey, another good idea would be to develop a GA airline business for passenger transportation to different islands of Bangladesh where a good number of tourists are interested in travelling; Cox’s Bazar to Saint Martin would be a good example route. Tourists can currently only travel by small ships from Cox’s Bazar to Saint Martin, and it is hard to visit Saint Martin Island and come back to Cox’s Bazar on the same day because, with small ships, it takes a long time. Many tourists would not take the risk of travelling on these small ferries due to their instability under sea conditions and long journey times. Furthermore, everything in Saint Martin Island is expensive, including accommodation. Therefore, small GA aircraft could be a perfect fit to meet this demand, although of course, many other factors should be considered before jumping into these kinds of new business model. In other cases such as air ambulance, marketing services, emergency medicine raw materials transport, agriculture and transport of police Quick Response Team (QRTs), etc., GA aircraft could also play an important role. Nevertheless, to fulfil these requirements, the aircraft range, price, maintenance and operation cost would be the prime selection criteria.

f. UAV conversion

In the age of exponential technological advancement, widespread adoption of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) is observed in many sectors such as agriculture, defence, fire service, surveillance, Three-Dimensional (3D) mapping, disaster relief, product delivery, Research and Development (R & D), reconnaissance, hobbies etc. In UAV systems, an autopilot system controls an remote-controlled aircraft platform. It is thus possible to convert any aircraft into a UAV if it meets the specific requirements in terms of manoeuvrability, payload capacity and stability as well as the specific mission layout. It would indeed be great if aircraft manufacturers could consider this scenario in advance, thus facilitating their conversion into a multi-use platform.

Bangladesh defence and other governmental and non-governmental organisations face new challenges during their development due to the varying demography and geoeconomic factors. In the near future, UAV conversion or multifaceted use is thus expected. As an example, the Bangladesh Army already added around 36 Bramor C4EY UAVs in 2018 for reconnaissance purposes [45] and more are under procurement according to the Directorate General Defence Purchase (DGDP) website [https://dgdp.gov.bd]. Therefore, consideration of this potential use-case and integrating it into the final design decision would be a wise step.

g. Disaster emergency rescue

As per the United Nations (UN) Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), “Asia and Pacific are the world’s most disaster-prone region” [Reference Zafar46]. Indeed, it has been considered that human life is at four times greater risk than in Africa and 25 times more than in Europe or North America [Reference Zafar46]. Bangladesh is susceptible to natural disasters because of its geographical location, environmental and climate change, and dense population [Reference Zafar46]. Therefore, in 2012, it had the fifth position in the world risk index as a country. Moreover, research has found that 68% of the country is vulnerable to flooding [Reference Zafar46].

Considering these facts, it is found that, before, during or after disasters such as floods or cyclones, insufficient effective systems have been developed to inform and manage such situations. As an example, cyclone warnings are broadcast on radio, television and mobile SMS networks and civil defence stations are informed by the central government to take action, part of which is to inform local inhabitants via loudspeakers about the cyclone so they can take shelter at cyclone centres (built by the government). Indeed, the availability of dedicated aircraft in such natural-disaster-prone areas could enable and facilitate informing people by dropping leaflets or the supply of emergency material as a precaution as well as for rescues. As a result, many innocent lives would be saved each year. Therefore, amphibious aircraft could be a solution, if they have the capability to operate in extreme environmental conditions.

3.1.4 Capability analysis

An indispensable feature of this study is that the selected emerging market should have sufficient resources and workforce to carry out the aircraft manufacturing project. There are many prerequisites for establishing a thriving aircraft industry. Most importantly, this requires infrastructure, skilled labour, government support and public acceptance. Environmental concerns are also becoming increasingly important. Let us look at what is currently available in Bangladesh and what improvements are underway to underpin aircraft manufacturing competence.

Recognising that infrastructure development is a prerequisite for transportation development, the Bangladeshi government has adopted several initiatives in different transportation sectors. Consequently, the aviation industry is receiving the highest priority due to the significant development of its market. According to the senior sales director of Airbus customer affairs, the Bangladesh aviation market has doubled over the last 7 years [Reference Islam31]. Undeniably, the Ministry of Civil Aviation has planned to develop a few airports in the country to meet the growing demand of the aviation industry. Several projects such as the development of Barisal Airport and the terminal building at Cox’s Bazar Airport, the construction of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib International Airport, the expansion of the existing runway at Osmani International Airport and the upgrade of Saidpur Airport to an international airport are already on the development roadmap [38]. A large-scale airport named Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib International Airport (BSMIA) has been proposed by the Bangladeshi government, having three long runways of 4,420m each in a total area of 8,000acres; it is expected to be completed in 2025 at a cost of 6.4 billion USD [47].

Surprisingly, there is no tax free/reduction allowance for domestic air transportation in Bangladesh. Conversely, the national carrier Biman Bangladesh Airlines is still in operation due to its government subsidy. Meanwhile, the Bangladeshi government is aiming to increase subsidies from 2019, with a target of earning 50 billion USD by 2021 to achieve higher growth and generate employment. Garment sectors are already receiving 2–4% subsidies in four categories [48]. At present, 26 category products are receiving subsidies ranging from 2–20% cash [48]. On the other hand, there is no clear roadmap for subsidies or government participation in home-grown aviation-related industries. However, the activity of the air transportation sector is significant to the local economy. The IATA evaluated three parts of the economy in 2018, viz. the labour, trade and tourism sector [49]. Resulting from the support of the air transportation industry of Bangladesh in 2018, around 129,000 jobs were located in the country by aircraft manufacturers, service providers, local services providers to air transportation and foreign tourists [49], hence supporting 769 million USD of Bangladesh’s GDP in 2018, representing 0.3% of the total [49].

To develop the aviation sector and bring the benefits of air transportation to the grassroots level, the Bangladeshi government has taken several initiatives: instituting an effective aviation safety net and an efficient cargo handling system, expansion of the tourism sector, increasing the number of domestic and international flight routes, increasing the number of airports, re-opening unused airports using innovative technology, i.e., Area navigation (RNAV) and remote airfield operation, modernising existing domestic and international airports as well as aviation-based education facilities. Moreover, the CAAB and International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) are working together on several projects to ensure safe and efficient aviation services.

However, in 2011, the Bangladesh government selected the Arial Beel in Munshiganj wetland area for the above-mentioned BSMIA airport, but the project was cancelled at that time due to protests from local farmers and fishers [Reference Husain and Kallol50]. This happened because of the local people’s lack of awareness of the economic advantages associated with an airport. However, it was the duty of the CAAB to engage local people through dialogue and other awareness-improving activities so they could understand and appreciate the need for aviation. However, this was not done in the right manner by the responsible authority, which is why the local people protested about the project. Consequently, the government had to pay twice the cost to a survey and feasibility study company Nippon KoE [36] Co Limited, and the project was delayed until 2025. It can thus be suggested that the CAAB requires appropriate action plans and activities in terms of engaging at the grassroots level.

Regarding the availability of skilled labour, the Ministry of Education has already adopted an initiative to institute an aerospace university, which will be the first aviation-related university in the country. Moreover, carious aviation colleges have been operating since 2008, already generating a substantial number of skilled workers, most of whom have been absorbed by the local airlines. However, it is frustrating that most of the workforce is not very familiar with aircraft manufacturing and design, despite having good aircraft maintenance knowhow. A substantial amount of training is thus required to prepare them for this specific industry.

Regarding the prospect of optimal usage of the limited air space, implementation of Performance-Based Navigation (PBN) through the CAAB could attenuate schedule disruption, passenger inconvenience, inefficient flight operations and higher environment pollution by improving operational facilities and reducing operational costs via fuel savings, noise reduction and a smaller CO2 footprint [51]. In view of the above-mentioned facts, the CAAB has already initiated new regulations and standards based on ICAO PBN standards since 2011 [51]. The new regulations cover the following criteria [51]:

-

• Standards for RNAV [51]

-

• Required Navigation Performance (RNP) and RNP AR routes/approaches [51]

-

• Route planning and flight procedure design criteria and validation procedure [51]

-

• On-board equipment standards for aircraft [51]

-

• Aircraft capability [51]

-

• Aircrew qualifications [51]

-

• Operation procedures [51]

-

• Certification and approval procedure [51]

-

• Monitoring and inspection [51]

-

• Air traffic command [51]

-

• Training standards for personnel (flight crew, maintenance, air traffic control etc.) [51]

It is strongly recommended that new aircraft manufacturers in the country consider the above-mentioned standards during their new aircraft design process. Moreover, Environmentally Conscious Manufacturing (ECM) is one of the key strategies in modern manufacturing industry. The adoption and implementation of ECM depend on multiple important enablers (e.g., economic, environmental and social enablers) and effective understanding of their interdependencies [Reference Ma, Song and Zhou52]. However, countries with emerging economies face additional challenges regarding the implementation of ECM compared with developed countries because of the improper implementation of environmental law, lack of awareness and indifferent mentality about sustainability as well as inadequate personnel trained on ECM. It is thus vital to establish a concrete sustainable plan beforehand to establish a GA aircraft manufacturing industry in emerging economies.

The use of renewable energy sources is an important effort to reduce carbon dioxide emissions and natural resource depletion and thus ensure environmental safety. The global direct carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from energy-related processes in the industry sector are projected to grow by 24% from 2014 to 2050 according to the latest International Energy Agency (IEA) Reference Technology Scenario (RTS) [36]. The identification of promising renewable energy sources and ensuring their proper utilisation would thus represent a milestone for emerging economies. In the aviation manufacturing industry, renewable energy sources such as sunlight with the aid of the latest technologies would assist in reducing carbon emissions and increasing the energy efficiency of countries such as Bangladesh. Bangladesh is located between 200° 30’ and 260° 45’ N and has a total area of 1.49 × 1011 m2 [Reference Mahmud53]. The average solar radiation is considered to be 5kWh/m2 over 300 solar days per annum [Reference Mahmud53], which could be regarded as suitable conditions to generate electrical energy from this enormous solar source for use in manufacturing plants. However, it is not always true that sustainability can be achieved by integrating renewable energy sources into the manufacturing process. Indeed, a viable waste management strategy also needs to be considered, as this is one of the biggest hurdles to emerging economy industries.

Based on the discussion above, it can thus be forecasted that the aviation economy of Bangladesh will observe a substantial improvement in the near future if the projected plans are implemented in a transparent manner. Moreover, we do not see many gaps in terms of resources and the workforce. If an entrepreneur comes up with innovative ideas and dogged determination, they could set a milestone in the history of aircraft manufacturing in emerging economies such as Bangladesh.

3.1.5 Price analysis

The greatest challenge and most significant part of a product is to come up with feasible pricing that could fit with customers’ purchasing power while also achieving the profitability targeted by the manufacturer. This decision model depends on many parameters. Therefore, to come up with a satisfactory anticipated price, we considered the cost of a luxury car in Bangladesh, because customers who buy luxury cars would be potential customers for the targeted GA aircraft. In other words, personal aircraft are mostly considered a status symbol, so we target the luxury car price as a baseline for aircraft manufacture. It is, of course, a challenge to meet a price tag similar to a luxury car.

One of the most common luxurious cars used in Bangladesh is the Toyota Prado, which has an average cost of 250,000 USD. Another popular model is the Nissan Patrol, which costs around 680,000 USD (based on our field survey). Some other popular models and their prices are listed in Table 3. One of the main reasons that these car prices are so high is the high taxes in Bangladesh (Table 4). Hence, it is important to note that the import tax for GA aircraft would not be as high as for luxurious cars (Table 5). Indeed, this would be another challenge for domestic aircraft manufacturers, as imported aircraft will be cheaper. Still, there is a chance for regional GA aircraft manufacturers to penetrate the existing market if they could offer five- to six-seater aircraft as a minimum like a luxurious car. However, the price of new GA aircraft will be comparatively higher on the international market compared with luxury cars. For argument’s sake, we assume a base price of 300,000 USD for an aircraft (in the range of a 5- to 9-seater) in this particular marketplace. Indeed, this assumption is thoroughly tackled in the “Results” section (Table 8), in addition to a confirmation that it meets the elicited raw requirements (cf. Table 4, section 4.4).

Table 5. Import tax on luxury cars [54]

Table 6. Import tax on aircraft and accessories [54]

3.2 Access FM

In the product design field, in most cases, requirements come from customers. Then, based on these requirements, designers or an engineering company perform the product design. For this paper, it is hard for our research team to implement this practical life scenario. Therefore, we tried to carry out the whole process the other way around: we first tried to understand the specific demographic needs through a market study based on ACCESS FM [Reference Hassan Shetol, Moklesur Rahman, Sarder, Ismail Hossain and Kabir Riday20]. To perform ACCESS FM, we define each letter in the abbreviation using a set of questionnaires (Fig. 3) that will provide a foundation for the raw requirements. In other words, this will deliver an outline of what to pick as raw requirements based on market research. After gathering this information based on the ACCESS FM aprpoach, we realised that some other important attributes of requirements were identified in the market study but not covered by the ACCESS FM questionnaires. It thus became necessary to include these important requirements using suitable platforms to enable their evaluation and verification in different regards. To achieve this, Quality Function Deployment (QFD) is applied below (“Results” section).

Figure 3. ACCESS FM questionnaire.

4.0 Results

In the book Materials-Enabled Design, Pfeifer claims that the development of design requirements depends on whether a product is designed by a type I or II company [Reference Pfeifer55]. In a type [36] company, design requirements are developed based on the wants and needs of the intended customer in relation to the intended product [Reference Pfeifer55]. These wants and needs must be identified by the company making the product, and often the captured needs are non-technical and sometimes vague [Reference Pfeifer55]. Type I [36] companies sometimes transform these vague needs into a measurable technical requirement and send to a type I [36] company to design the product accordingly [Reference Pfeifer55]. In some cases, the type I [36] company may also manufacture the intended product [Reference Pfeifer55]. In the aviation industry, this type of company is often known as an Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM). On the other hand, the activities of type [36] I [36] companies may sometimes be carried out by the same company. In the current context, the activities of type [36] companies can be supported by the discussion in the sections above. Indeed, the list of raw requirements and the development of technical requirements based on them are still lacking. Therefore, in this section, we collate the raw requirements and analyse their fitness using QFD. Moreover, a use-case diagram is also developed to help designers understand the diverse functions in relation to the diverse users in an emerging economy while establishing the final design specification. Thereafter, some of the key technical requirements are specified by using constraint analysis and factual cost examination throughDevelopment and Procurement Cost of Aircraft (DAPCA) IV method, discussed below [56]. Additionally, this will help designers evaluate different views and define appropriate requirements.

Figure 4. Quality Function Deployment (QFD).

4.1 Quality Function Deployment (QFD)

The “good requirements” (Fig. 4) [47] identified by the ACCESS FM technique and market study according to the IVY Hooks method [Reference Hooks10] then had to be analysed to determine their feasibility in engineering applications. To evaluate those customers’ requirements, technical measures were generated based on our understanding, and QFD was performed (Fig. 4), essentially providing a rank order of the technical measures. These technical measures are very important to the engineering design team in terms of design analytics as well as to deliver a purposeful solution to the particular problem. To understand and analyse competitors against these design decisions and effectively use them in the QFD approach, relevant data were collected from manufacturer websites (Diamond Aircraft, CTLS, Sling4, Icon, Cessna and Piper). These data were used to perform the ‘customer competitive assessment’ part of the QFD. However, a description of the whole application process and the attributes of the QFD lies beyond the scope of this study, as this tool is familiar in the engineering design realm. Indeed, only the most important parts of this tool are described in the next section.

The dominant part of the QFD technique is known as the House of quality (HOQ) matrix, consisting of six main features: (A) customer requirements (WHATs), (B) assessment of competitors, (C) technical measures (HOWs), (D) relationship matrix between WHATs and HOWs, (E) technical correlation matrix and (F) technical matrix, as presented in Fig. 5 [Reference Alrabghi57]. To perform QFD, the customer requirements are selected in relation to the market study and ACCESS FM as well as analyses of available similar types of aircraft. The technical measures for the QFD are considered as per our research team’s knowhow and expertise in the field of aircraft design. In other words, the customer requirements are translated to form the basis of the engineering measures. The relationship matrix of WHATs versus HOWs is then used to identify the degree of relationship or linkage between each customer requirement and the technical measures. It is situated in the centre of the HOQ and is populated by the research team. It is considered to be the principal part of the QFD process since the final analysis stage profoundly depends on this relationship between WHATs and HOWs.

Figure 5. Different active parts of the QFD [Reference Alrabghi57].

As we are not designing a real-life product but considering real-life scenarios, we analysed our aircraft (code name BBRG-20) and compared it with competitors in the ‘competitor assessment’ stage. The relationship matrix is constructed using no, weak, moderate and strong relation, indicated by weights of 0, 1, 3 and 9, respectively. A technical correlation matrix was built based on this analysis in the field of engineering, showing positive, negative and no correlations. However, this is the least important part of the QFD process because it has no effect on the final result. The purpose of the ‘technical matrix’ is to afford an initial rank order of the relative importance of the technical measures extracted from the user information in different parts of the HOQ, enabling the engineering design team to map and propagate the design solutions.

4.2 Use-case diagram

The analysis above reveals that requirements elicitation is one of the central elements of requirements engineering, mostly being employed to research and discover the requirements of a particular system from its stakeholders [Reference Sommerville and Sawyer58]. Although it is important to note that requirements elicitation is not simply a collection process in this case because we also tried to remove unnecessary requirements. Nevertheless, before declaring some requirements to be unnecessary, it had be verified that the customer requirements articulated in the QFD (Fig. 5) are justified in relation to the use cases. However, to visualise the functional scenarios of a given system (GA aircraft) in relation to its users, a SysML use-case diagram must be constructed. Indeed, “[a] use-case diagram shows communications among system transactions (use-cases) and external users (actors) in the context of a system boundary (Subject; notation: rectangle); actors may represent wetware (persons, organizations, and facilities), software systems, or hardware systems, which, defining relationships between the system subject and the system actors is an effective informal way to define system scope” [56], which may help one to re-evaluate the customer requirements considered in the QFD as described in the “Results” section. Therefore, a SysML use-case diagram (Fig. 6) was formed, providing a higher-level functional view of the system in relation to its potential customers in a simplified graphical representation to demonstrate the actual functions of the system. The use-case diagram reveals that the customer requirements revealed through the QFD are more or less related to the different types of customers. Indeed, ‘posh look’ and ‘comfortable’ are applicable for use case no. 1, while ‘safe’, ‘reliable’ and ‘less operational cost’ apply for all the considered user types (Fig. 4). One can thus deduce that the elicited requirements are in accordance and ready to play their part in a harmonised design process. Additionally, this use-case diagram can be used when defining the final requirements as a verification scenario.

Figure 6. Use-case diagram of the projected GA aircraft.

According to the QFD technique, use-case diagram and ACCESS FM questionnaire analysis, our research team agreed to focus on a six-seater aircraft as the target configuration. On the one hand, based on our initial examination, a nine-seater aircraft would be suitable, but above six seats the cost tends to increase non-linearly in every respect (based on the cost analysis, not presented herein as it lies beyond the scope of this work), which is not in line with our projected intrinsic and extrinsic goals. On the other hand, configurations with fewer than six seats could not cater for all the use-cases. The targeted use-cases derived from the market study are shown in the use-case diagram in Fig. 6.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to find a suitable range for the projected aircraft because different criteria are involved. Bangladesh measures 442nm from north to south and 324nm from east to west [26]. After considering overall safety measures and covering the maximum range, 700nm was set as the initial target range for an amphibious GA aircraft. To verify this decision, we cross-checked against similar types of aircraft and found this assumption to be in the right order of magnitude. For the projected aircraft, the payload is the pilot plus five passengers with baggage, corresponding to 165 + (200 × 5) = 1,165lbs or 528kg, with the possibility of increasing the maximum payload to 600kg. Similarly, the maximum take-off weight and empty weight are calculated to be approximately 1,322kg and 650kg, respectively. Nevertheless, the access door type, size and clearance above the ground are challenging to select due to the different use-cases considered. This will be dealt with in the detailed design phase, but for now and based on the specifications described above, a constraint diagram using the Gudmundsson approach [56] was constructed (“Results” section) to re-evaluate and make these decisions. This may lead to further design steps such as preliminary design and detail design.

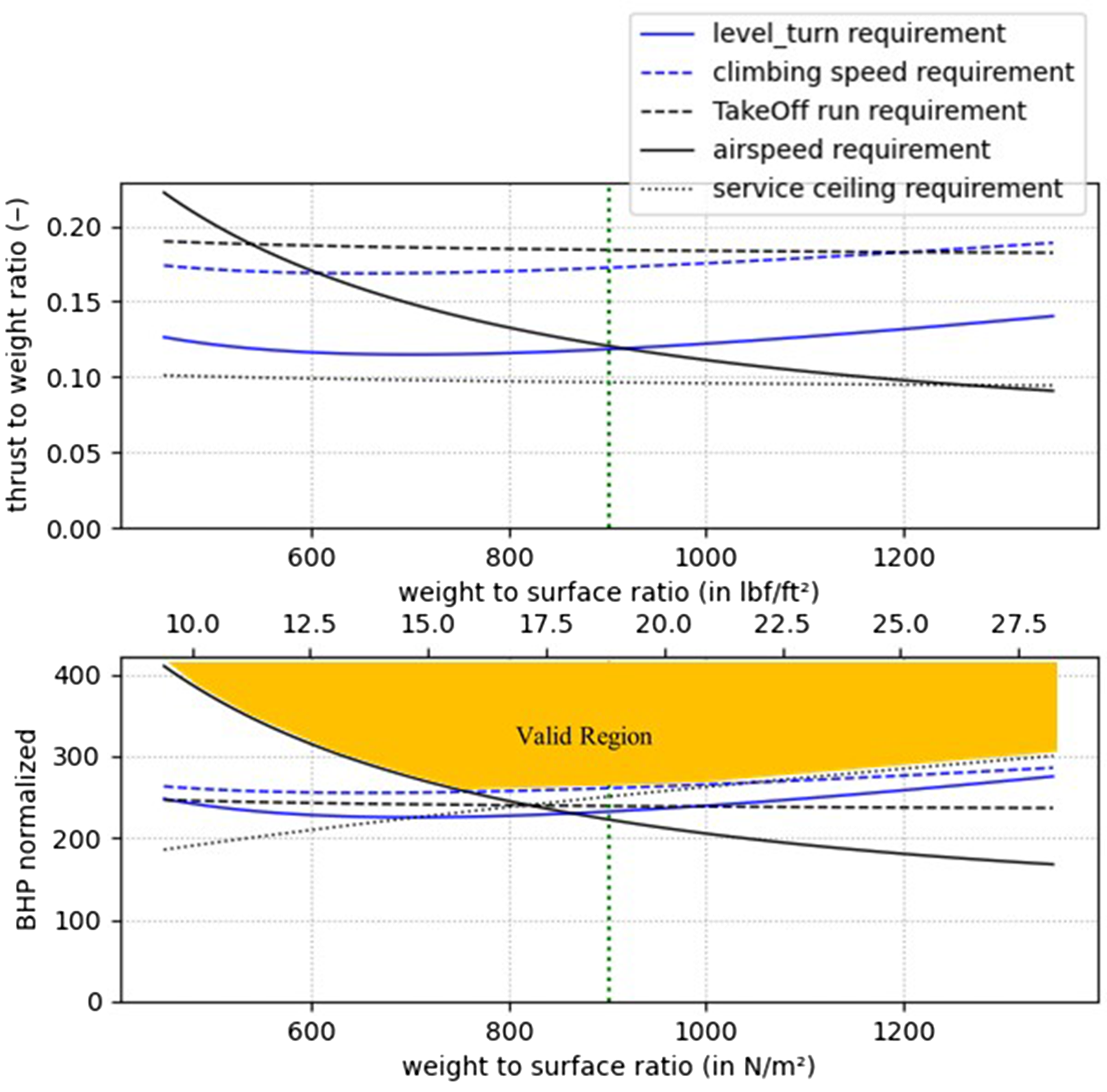

4.3 Constraint analysis

Constraint analysis is one of the first steps when designing a new aircraft. It enables an estimation of the required wing area and power plant based on multiple performance requirements. Each constraint is plotted as a separate line, with the axes typically being the thrust-to-weight ratio and the wing loading (i.e., the weight per surface area). Since we considers a propeller-driven aircraft, it is best to convert the thrust to engine power. Furthermore, the performance of the engine may change significantly with altitude. This must be accounted for by using a slightly modified diagram in which the equivalent engine power at sea level is plotted against the wing loading, although the basic principle remains unchanged.

As shown by this example, the conversion from thrust to equivalent engine power at sea level changes the constraint lines slightly. On the one hand, this occurs because the power is the product of the force and speed, and these flight phases have different speeds. On the other hand, the altitude also affects the power output of the engine itself, with the greatest impact being observed at the service ceiling.

Any point in this two-dimensional design space with all conditions above the constraint lines is in the “valid region” (yellow area in Graph 2) based on the individual requirement scenario. Selecting a specific solution is a design decision. Usually, it is expensive to exceed the requirements, so a solution that caters for all the requirements adequately but without exceeding them is preferred (i.e., remaining at the lower edge of the valid region). To compare our considerations against existing solutions (i.e., other aircraft), we calculate their thrust-to-weight ratio and wing loading (Table 7) and simply draw each solution as a point on this graph (Graph 2). We can also interpolate some of the specifications of other aircraft (e.g., the climb rate from Table 7) onto our constraint line for a comparison and to observe the deviations.

Table 7. Six-seater aircraft’s key specifications [source: manufacturer’s websites]

Table 8. BBRG-20 cost calculation through DAPCA IV

Graph 2 shows the chosen constraints. If the weight-to-surface ratio is anywhere between 700 and 1,200N/m², an engine of about 270 or 280hp will be needed. It is probably no coincidence that most aircraft in this class (from different manufacturers) have engines with about this power. In Graphs 1 and 2, the green line represents a weight-to-surface ratio of 900N/m, which is based on our currently targeted design constraints. This constraint analysis is coded using Python and included in Appendix A1.

4.4 Factual cost examination

In the QFD, in the customer requirements part, we devised one requirement, viz. cheap. Unfortunately, that does not define “cheap” in terms of monetary value. However, in the price analysis section, we proposed a base price of 300,000 USD, which provides the essence of the projected price. Evidently, we could not verify this proposal. Therefore, we calculated our imaginary aircraft BBRG-20 by following the DAPCA IV method, finding that our guesstimate is indeed in the right ballpark [Reference Gudmundsson and Gudmundsson59]. The DAPCA IV (revised) method was applied, targeting 1,000 units of aircraft production in 5 years. The calculation was conducted based on two different materials, namely aluminium and composite, yielding a development cost (only applicable for conventional aircraft) of 177,519 USD and 233,772 USD, respectively. Adding a 20% profit margin, the base selling price for the aluminium and composite aircraft becomes 213,023 USD and 280,526 USD, respectively. The partial calculation is presented in Table 8. We do not describe all the features of this cost calculation, which would result in additional discussion beyond the scope of this study. Interestingly, this cost examination part is taken as an avenue for future research. Furthermore, another requirement in QFD is ‘less direct operating cost (DOC)’, which could also be examined by applying the DAPCA IV method for operating cost, although we have not targeted this herein.

Graph 1 Constraint diagrams.

Graph 2 Constraint diagram with aircraft specification for comparison (coded with Python, see A1).

5.0 Discussion

This study demonstrates the requirements elicitation process for a GA aircraft for an emerging market by considering all the potential variables and analysing the limitations of current modes of transport. However, it could be proposed that GA amphibious aircraft would provide a stepping-stone for Bangladesh’s chaotic transportation system, which might be one of the important routes for further economic development. An amphibious aircraft could travel to most places in the country in a short time (considering all safety requirements) despite the regular flooding and sea-level rise along coastal areas. This would thus provide an innovative instrument for commerce within the country as well as opening a new horizon for consumer travel by connecting inaccessible destinations.

However, this would only be possible if the aircraft has a lower price, less maintenance and less operating costs compared with the same type of aircraft currently available on the market. In this context, in the “Result” sections (QFD) of this paper, the technical measure ‘production cost’ has the highest value (489) and exhibits an influential relationship with all the customer requirements identified in the QFD. Furthermore, ‘weight’, ‘materials’ and ‘dimensions’ were ranked in the second, third and fourth positions with 464.5, 443.4 and 392.6 points, respectively. All these rankings are relevant, describing the correct fit for the aircraft design and manufacturing process. As an example, if one wants to keep production cost low, one must consider the correct material. Meanwhile, the materials selection also depends on the weight and manufacturability, thus the weight is also related to the dimension of the aircraft. Engineering common sense thus indicates that the rank order in terms of technical importance is logical, with substantial dominance over one another and the same chronological dependence up to the last rank. This will help potential future manufacturing companies to re-evaluate their significant needs in relation to the QFD approach to achieve purposeful solutions. It can thus be deduced that the requirements emerging from the market study exhibit strong logical engineering dependences that could help to define a viable Product Life Cycle (PLC) for the design and manufacturing process of the GA aircraft.

Although the difficulties and dependences could be measured through the QFD process, the difficulties in the operation and maintenance part of the aircraft PLC could not be analysed. The market study section thus focused on a deeper inspection of the current state of aircraft operations in the country. This reveal that many existing aircraft owners struggle with the heavy maintenance activities (e.g. C & D checks) due to a lack of capable Maintenance, Repair, and Operating Supplies (MRO) companies for deep maintenance. Nevertheless, the price of aviation fuel in the USA is almost twice that in Bangladesh. These facts must also be considered beforehand, rather than using a target selling point that could never be reached because consumers buying low-cost aircraft will be disgruntled if their operation cost is then too high. Companies should include this in their business strategy to ensure that buyers are satisfied and will attract new buyers.

One of our main claims in the literature review section is that the proposed requirements elicitation process can be carried out while avoiding more time-consuming methods, such as stakeholder interviews with a questionnaire, focus-group interviews, requirements workshops and surveys. However, this claim can only be verified if a company attempts to implement it in a practical aircraft design and finds it to be correct. Even if this claim is confirmed in an actual application, we recommend that stakeholder interview with questionnaires still be performed to confirm the real scenario of the product in the marketplace.

Based on the “Results” section, we have defined a set of raw requirements based on the specific demographic and socio-economic characteristics. These raw requirements are then transformed to measurable specifications by applying constraint analysis and cost examination. In this transformation, a few raw requirements such as the number of seats, range, weight, cost, engine power, wing area, etc., are considered to illustrate the application of this process. Indeed, this transformation is the ultimate goal of requirements engineering. Undoubtedly, the current work successfully demonstrates that the described procedure for requirements elicitation can be used in an unknown and volatile market for a unique product as an integral part of requirements engineering. Consecutively, in the literature review section, we set our goal to achieve good requirements according to Hooks [Reference Hooks10], which has also been proven by demonstrating the transformation from the raw to final requirements. The identified requirements indeed define the needs, attainability, clarity and verifiability [Reference Hooks10]. Most importantly, we now explicitly know the answers to the following questions: Why have we chosen these requirements? Are they quantifiable? Is it possible to attain them? What is their origin? Who are the potential users? For clarity, the quantifiable requirements are presented in Table 9.

Table 9. Summary of the discussed quantifiable requirements

It is no surprise that we may have missed some factors that might impact on the overall requirements. As emerging economies are volatile and this study was carried out based on the present situation, it is hard to prescribe the change in such requirements in the future. Since aircraft development cannot be achieve in one or two years, it is also not certain that the characteristics of all emerging markets around the world will be similar. Hence, this study might not be appropriate for other emerging economies as the socio-economy and geopolitical situation will differ from region to region.

It is thus recommended that new aircraft manufacturers should consider all of these scenarios and identify an effective solution before starting aircraft manufacturing. Further consideration may be required in terms of changes in legislation in line with international standards and a certain level of customisation required to address local needs. The government can provide tax relief and financial packages to promote home-grown products for domestic customers, and this may kick-start aircraft manufacturing in the country.

6.0 Conclusions

In general, the source of each final or key requirement is the raw requirements, which themselves originate from the system’s operational perspectives. Therefore, this comprehensive study is carried out by analysing the targeted system, users and organisational context, encompassed within the diverse scenarios of an emerging economy. All these contexts and scenarios are guided by the functional, behavioural and physical viewpoints. The results show that this holistic approach can be used to (i) elicit GA aircraft design requirements for the targeted emerging market and (ii) generate the main end-user requirements. Hence, GA aircraft can be designed from a blank drawing board, as already demonstrated in the “Results” section. The proposed process outlined in the “Methods” section also helps us to carry out this study systematically.

In addition, current (in-service) GA aircraft are not appropriate to fulfil the diverse use-cases considered, which are essential to fit emerging economies. Moreover, the GA aircraft design and manufacturing process is out of date, expensive and environmentally unsustainable compared with the revolution observed in road transport. Therefore, immense opportunities await the right motivation, removing this as an obstacle and as demonstrated throughout this paper.