In the last few decades, the use of digital tools has transformed the way archaeologists excavate, research, present their data, and teach (see, for example, Graham et al. Reference Graham, Gupta, Smith, Angourakis, Reinhard, Ellenberger, Batist, Rivard, Marwick, Carter, Compton, Blades, Wood and Nobles2020; Heath Reference Heath2020; Kansa et al. Reference Kansa, Kansa and Watrall2011). Digital games, however, have yet to be embraced as a tool by the archaeological community in general, despite recent scholarship regarding the potential that such media present for both research and teaching (for example, Politopoulos, Ariese, et al. Reference Politopoulos, Ariese, Boom and Mol2019; Reinhard Reference Reinhard2018; Rollinger, ed. Reference Rollinger2020). I use the term “digital games” to refer to all games played on consoles with a screen, on a digital handheld device, or on a computer. The VALUE Foundation, a group of scholars who study archaeology and digital games, have demonstrated that even archaeologists who enjoy playing these historical or archaeologically related games generally do not consider them to be of significant merit for presenting or researching archaeological topics (Boom et al. Reference Boom, Ariese, van den Hout, Mol, Politopoulos and Hageneuer2020; Mol et al. Reference Mol, Ariese-Vandemeulebroucke, Boom, Politopoulos and Vandemeulebroucke2016:12–13). Many seem to view these games purely as play, and dismiss these resources due to their overly simplistic, violent, or inaccurate representations of historical topics or the practice of archaeology (McCall Reference McCall and Rollinger2020:107; Politopoulos, Ariese, et al. Reference Politopoulos, Mol, Boom and Ariese2019:164; Rollinger Reference Rollinger and Rollinger2020a:2). Discussions with colleagues have revealed that although a few are open to the concept, most are not prepared to consider using this medium in the classroom. The exception seems to be scholars who work closely with digital laboratories and projects, and who—more often than not—discuss modifications to games and the redesign of virtual ancient environments with students and the public (Boom et al. Reference Boom, Ariese, van den Hout, Mol, Politopoulos and Hageneuer2020; Champion Reference Champion2011:111–116; Majewski Reference Majewski, Mol, Ariese-Vandemeulebroucke, Boom and Politopoulos2017; Morgan Reference Morgan2009; Politopoulos, Ariese, et al. Reference Politopoulos, Mol, Boom and Ariese2019). Relatively unaltered games, however, could also be used to inspire and enhance discussions in a variety of courses, with—in most cases—a relatively minor financial investment. With the rise in popularity of digital games, such discussions are becoming increasingly important.

A recent survey by the Entertainment Software Association (2019) found that 65% of American adults play digital games. As a major source of entertainment, the public—which includes undergraduate archaeology students—is engaging with this medium and learning from it, whether scholars find it valuable or not. Instead of ignoring this resource, archaeologists can instead use this popular medium to their advantage in the classroom, as a few scholars have already demonstrated (Boom et al. Reference Boom, Ariese, van den Hout, Mol, Politopoulos and Hageneuer2020; McCall Reference McCall2011). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, digital teaching materials are increasingly in demand, causing digital games to be even more useful.

In this article, I discuss the potential of unmodified digital games for engaging students and encouraging a critical examination of new media. I review the manner in which games can be used as simulations to help explain historical and archaeological processes and systems, and in which games set in historic contexts can spark debates about popular representations and reconstruction choices for different audiences. I then review my own experience of teaching about ancient Egypt with help from Ubisoft's Assassin's Creed: Origins.

CRITICAL ENGAGEMENT AND DIGITAL GAMES

In Canada and the United States, many of the undergraduate students who take our courses are not archaeology majors. They are using these classes to fill “General Education” or “Outside Program” requirements. These students, as well as those beginning their study of archaeology, often cite Indiana Jones, The Mummy, or Assassin's Creed itself as the inspiration behind their course selection. Many of these undergraduates are often disappointed to discover that the subject matter is not as dramatic as it is portrayed on screen. Keeping students engaged while fostering critical discussions of archaeological theory and method, or reconstructions of ancient architecture, is therefore frequently a challenge.

The inclusion of multiple media resources alongside traditional text-based lectures and readings is a well-established means of engaging students, and it has been shown to improve knowledge retention and comprehension (see Haarstad Reference Haarstad and Strawser2017:84–86; Mayer Reference Mayer2001). Although images and videos are frequently integrated into coursework for this purpose, digital games have the potential to take these experiences further. As Jeremiah McCall (Reference McCall2011:19) states, “Video games are multimodal, communicating through visual, tactile, and auditory channels. They engage a learner through more than one or two channels of normal classroom instruction.” The ability to actively explore and interact with these media immerses the student as a player in a way that film and television, for instance, do not. Digital games allow students to take an active role in exploring and interpreting archaeological concepts and environments (Chapman Reference Chapman2016:33; see also Gee Reference Gee2003:13–50).

The use of digital games in the classroom also helps students connect the material to interests in their personal lives. Although this is valuable for students who are already interested in archaeology, this is especially important for those who are new to the subject and who might not otherwise perceive significant value in the course content (Ambrose et al. Reference Ambrose, Bridges, DiPietro, Lovett and Norman2010:69–75). Branching out into this popular medium can therefore help encourage students who feel less comfortable with the more formal elements of the course to participate in class discussions, potentially drawing on a different area of their expertise (see case study below).

These engaging activities can then be used to frame critical discussions about not only historical and archaeological content and systems but also how to interact with and assess new media. “New media” is generally defined as media that is associated with digital communications (for discussion, see McCall Reference McCall2011:92–93). Encouraging students to think critically about the use of new media is widely considered a significant goal of modern education (McCall Reference McCall2011:11; National Council for the Social Studies 2009), and it is particularly relevant for the field of archaeology. As a number of scholars have demonstrated, popular depictions of archaeology in film, television, and digital games are full of inaccurate, pseudoscientific, racist, and colonial portrayals of ancient and modern cultures as well as archaeological practice (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Card and Feder2013; Card and Anderson Reference Card, Anderson, Card and Anderson2016:3; Reinhard Reference Reinhard2018:71–75; Wade Reference Wade2019). Discussing these media in class can help to correct misinformation that a student may have unwittingly absorbed while engaging with these sources previously, and it will provide them with a more stable foundation of knowledge as they continue to learn (see Ambrose et al. Reference Ambrose, Bridges, DiPietro, Lovett and Norman2010:14).

Encouraging students to consider different approaches to studying and portraying historical topics critically can also help them to not only reassess more traditional interpretations but also question the validity of a single, “correct,” historical or archaeological narrative (see Chapman Reference Chapman2016:9; Uricchio Reference Uricchio, Raessens and Goldstein2005). The hope is that after critiquing these sources in the classroom students will continue to think carefully about the use of other media they encounter in both their professional and personal lives. The wide variety of digital games currently available can enable and enhance critical discussions related to a number of topics surrounding archaeology and its popular representation.

DIGITAL GAMES AND “CONCEPTUAL SIMULATIONS”

In the selection of games for use in the classroom, it is best to consider first what type of discussions you hope to have with your students. Although there is significant overlap in game types, and different ways of classifying games, I have found it helpful to begin by considering two broad categories that are effective for discussing historical and archaeological topics: those games that can be considered primarily “conceptual simulations,” and those that are primarily “realist simulations” (as defined by Chapman Reference Chapman2016; see also Uricchio Reference Uricchio, Raessens and Goldstein2005; for alternatives, McCall Reference McCall2016). Conceptual simulation games are those that use a complex set of rules to model historical and archaeological processes. Such games might include, for example, Age of Empires or the Civilization series, in which players must build up communities by prioritizing different “technologies”—such as forging, construction, or warfare—in order to create a prosperous civilization (see Flegler Reference Flegler and Rollinger2020). These are games that lend themselves more easily as models to help engage students in discussions of anthropological theory and the process of archaeological interpretation. The visual realism of the games and their references to specific historic events or monuments are therefore not as important as the “procedural rhetoric” of the game design (Chapman Reference Chapman2016:71). McCall promotes these types of games for use in secondary history courses, noting that they are able to “model complex real-world relationships and systems in ways that are nearly impossible for static words and images” (Reference McCall2011:1, Appendix A). Scholars in the small but growing subdiscipline of archaeology referred to as “archaeogaming” have provided a number of examples of how such games can model interactions between people, places, and materials.

Meghan Dennis has defined archaeogaming as “the utilization and treatment of immaterial space to study created culture, specifically through video games” (as quoted in Politopoulos, Ariese, et al. Reference Politopoulos, Mol, Boom and Ariese2019:165). This goes beyond the study of popular realist simulations, which I discuss below, and includes the testing of archaeological theories and concepts in a digital landscape and through the consideration of the systemic construction of game design and mechanics (see Politopoulos, Ariese, et al. Reference Politopoulos, Ariese, Boom and Mol2019:165–167; Reinhard Reference Reinhard2018:2–3). Tara Jane Copplestone, for instance, has drawn on the networks involved in game design to explore how to communicate the process of archaeological interpretations.

In several publications, Copplestone (Reference Copplestone, Mol, Ariese-Vandemeulebroucke, Boom and Politopoulos2017a, Reference Copplestone2017b) notes that the traditional use of linear narratives in written reports oversimplifies much of the archaeological process. As archaeologists excavate, they are constantly interpreting the evidence and making subsequent choices about how to proceed based on those interpretations. The full process of analysis—and the different systems that have been consciously connected, selected, or ignored—cannot be adequately communicated though a linear narrative. Through video game construction, however, Copplestone argues that it may be possible to communicate how different choices might change the ultimate interpretation of the evidence, just as selecting different options in games produces different results. As she states, “Creating, processing, and communicating through the video game media form means taking a distinctly systems based approach whilst, due to the necessity of player agency, allows for multivocality, multilinearity, and reflexivity at the point of play” (Copplestone Reference Copplestone, Mol, Ariese-Vandemeulebroucke, Boom and Politopoulos2017a:94). In this way, by using game design and play as an analogy for the process of archaeological interpretation, students may be better equipped to consider its subjective nature and to question and critique the linear conclusions they read both in their textbooks and during their research. In other instances, the “microworlds” created in certain games can be used to assess different aspects of human and object interactions (see also McCall Reference McCall2011:18, 23–30). This is the approach taken, for example, by Angus Mol.

Mol has completed considerable research related to archaeology and digital games, including the use of digital worlds to test and reconsider archaeological methodology. In one such project, he examined the creation and movement of objects in the role-playing games The Lord of the Rings Online, DayZ, and Diablo III in order to reflect on “the ‘socio-material’ dynamics of online social networks” (Mol Reference Mol2014:144). Mol tracked the movement of digital objects in the game and noted associated social interactions. This helped to simulate the long life spans of objects, the networks through which they can move, and the different types of relationships they can foster. The study of these virtual universes can, as Mol states, “make significant contributions to our understanding of how society and material culture form interdependent systems” (Reference Mol2014:161). Encouraging students to use games to model how objects, cities, and civilizations are created and changed, and the interactions involved between players and objects, may help to clarify and reinforce complicated topics in ways that reading thick theoretical papers cannot.

As these few examples show, digital games can be used alongside more traditional lectures and readings as tools to engage students in discussions of archaeological theory and methods. For this, there is considerable flexibility in game choice, depending on the discussion you wish to promote in your classroom. As demonstrated by these examples, however, playing the games should be used as a starting point for more critical discussions. Although games are better at modeling complex relationships than linear texts, they cannot simulate the full complexity of the real world, but they are still bound by programed rules (McCall Reference McCall2016:528–529). Students should therefore be encouraged to consider the weaknesses or oversimplifications that remain in the games, which is in itself a valuable learning opportunity (see McCall Reference McCall2011:14–17).

DIGITAL GAMES AND “REALIST SIMULATIONS”

On the other side of the spectrum of historical games are those that Adam Chapman (Reference Chapman2016) refers to as “realist simulations.” These are games in which an attempt has been made to create an “authentic” representation of the past “as it appeared to historical agents of the time,” usually through audiovisual elements (Chapman Reference Chapman2016:61, 64). These games—such as the Call of Duty series, Medal of Honor series, or Assassin's Creed series—all take place in a specific time period and usually make reference to historic events, people, and monuments. Consequently, the main narrative of such games is usually more structured (Chapman Reference Chapman2016:66). These types of resources are more valuable for encouraging discussions of specific events, monuments, and choices in visual reconstructions.

Historians seem to be divided on the value of realist simulation games for education, with merits usually discussed on a case-by-case basis. McCall (Reference McCall2016:519), for instance, notes that Call of Duty, in which the player takes on the role of an infantry soldier in World War II, is more valuable than the Assassin's Creed (AC) games, in which the player is an “unhistorical agent” (see also McCall Reference McCall2011:28–30). The AC games, in particular, are controversial. Each game in the series focuses on a group of assassins that is trying to save the world from an opposing group of conspirators, which both includes and affects historic personalities from various periods and global regions. Although each game involves major events in history, the player interacts with them somewhat infrequently and is instead usually working on the sidelines to assassinate largely fictional enemies. As Politopoulos, Mol, Boom, and Ariese (Reference Politopoulos, Ariese, Boom and Mol2019:321) state, “The violent story of the player as protagonist is disconnected from any historical reality.” In general, these types of games also incorporate additional fictional and fantastical elements that can veer significantly from the history constructed from scholarly consensus, including the ability to play following an alternative historical narrative.

Despite the validity of these criticisms, Chapman and others have argued that historical digital games should still be considered valuable as an alternative means of engaging with history. He argues that “counterfactualism, anachronism, and the loss of historian's authority, do not necessarily indicate a lack of useful discourse ” (Chapman Reference Chapman2016:47; emphasis in original; see also Copplestone Reference Copplestone2017b; Elliot and Kapell Reference Elliot, Kapell, Kapell and Elliot2013; Uricchio Reference Uricchio, Raessens and Goldstein2005). History students can benefit from playing through and discussing historical alternatives. I would also argue that for archaeologists, who are concerned with how to visualize and reconstruct ancient natural and constructed environments, a detailed assessment of the historic backdrops of these games can lead to significant critical discussions. These can go beyond a simple identification of errors in representations so that students can instead discuss why game designers make certain decisions, how they “go about producing ‘authenticity’” (Rollinger Reference Rollinger and Rollinger2020a:6), and how this can affect the resulting image of the past. For these discussions, the detailed and well-researched reconstructed worlds of realist simulation games are valuable, as demonstrated in particular by the AC games.

The AC games are frequently lauded by scholars for their vast, open, explorable, and detailed reconstructions of ancient environments (for instance, Casey Reference Casey2018; Rollinger Reference Rollinger and Rollinger2020b:38). These are created based on considerable research and with the help of academic advisors. With respect to AC: Origins, which was released in 2017 and set in Ptolemaic Egypt, Maxime Durand—a historian working for Ubisoft—has discussed some of the choices the production team made in reconstructions. He noted that they incorporated, in particular, the work of Egyptologist Mark Lehner to help visualize the sphinx and ancient Giza; however, they also included elements of other theories in their reconstructions (Nielsen Reference Nielsen2017). The ancient world they create is therefore a synthesis of scholarly opinion (Rollinger Reference Rollinger and Rollinger2020b:38), with creative additions to enhance gameplay. In addition to famous sites, the game designers have also researched the flora and fauna of the time, religious and mundane objects, craft traditions, and diverse cultural practices and languages, adding in these elements—what Chapman (Reference Chapman2016:123) would refer to as “lexia”—to ensure that the game environments are more authentic, if not absolutely historically accurate (Nielsen Reference Nielsen2017; see also Elliot and Kapell Reference Elliot, Kapell, Kapell and Elliot2013:13–14; Serrano Lonzano Reference Serrano Lonzano and Rollinger2020:56). All of these elements can be explored and discussed with students. Ubisoft has also enhanced the educational value of the most recent Assassin's Creed installments by adding the Discovery Tour.

The Discovery Tour is a version of the game that allows players to walk through the re-created open ancient worlds without the violent battles. Players can also follow curated tours about different ancient sites or social and religious practices. In the tours, a voice-over describes the different elements and mentions a number of the discrepancies between what is seen in the game and what the evidence suggests—specifying where additions have been made to enhance gameplay. This means that such resources can be used as, in Ubisoft's own words, “a virtual museum” (Ubisoft Reference Ubisoft2021). With the violence removed, the game can safely be used in the classroom to explore the carefully reconstructed monuments and additional tours, although admittedly at the expense of the more interactive narrative elements (Mol Reference Mol2018; Politopoulos, Mol, et al. Reference Politopoulos, Ariese, Boom and Mol2019).

As with the conceptual simulations, realist games are much more valuable for undergraduate teaching when they are used to supplement more traditional lectures and readings (see also Porter Reference Porter2018). The tours and additional selections can help students visualize the ancient context under study, and they can foster engaging discussions about various topics—such as inaccuracies in representations, different reconstruction choices, if and how these models are better suited for popular audiences, and how scholars may have approached these models differently.

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS AND POTENTIAL CHALLENGES

Although a variety of digital games can lead to excellent, engaging experiences in the classroom, there are, of course, a number of additional practical considerations and challenges. If you have little experience with digital games, there will be a necessary period of adjustment while you experiment with different options. You may want to start by reading through the lists of simulation games and descriptions prepared by McCall (Reference McCall2011:133–172, Appendix A), review the list of games set in the ancient world by Rollinger (Reference Rollinger and Rollinger2020b:27, Table 1.1), or explore the Discovery Tours in Assassin's Creed: Origins or Assassin's Creed: Odyssey (set in ancient Greece). Also, you should carefully consider those games with explicit content or those rated “M” (for mature audiences). In these cases, you should determine which scenes are inappropriate to show in class and/or warn your students about any possibly upsetting content in advance.

Once you have selected a game, you will need to consider the platforms to which you, your department, and your students have access. If you plan to explore the games together in class, you should check the system requirements, ensure that you have access to the hardware and software required, and verify that they can be connected to your classroom projection systems. If you are planning to play the games in a computer lab, check in advance that the computers will support your selection. If you select a game that is accessible online and you plan to ask your students to play at home, it is best to choose one that can be played on Microsoft, Apple, and Linux operating systems without advanced graphics cards. This ensures greater accessibility for your students (see further logistical considerations in McCall Reference McCall2011:173–184, Appendix B). If in doubt, you can always reach out to your IT department for assistance and advice.

The question of cost is also always a central concern. Many games can be played online or downloaded as phone applications for free. Although the Discovery Tours are included in the full versions of AC: Origins and AC: Odyssey, they can also be purchased separately at a significantly reduced price. Ubisoft also offers selected games for free on rotation, which in May 2020 included the Discovery Tours (for the current selection, go to https://free.ubisoft.com/ ). There are several ways to avoid the need for students to purchase the games themselves. If you are teaching in person, you can hold additional office hours or ensure computer lab access to give students the opportunity to play the games on their own time. If you are teaching an online course, you may want to consider (1) the freely available games, (2) screen-sharing or streaming options, or (3) recording different elements of gameplay that can be shared with the students (see Etienne and Faulkner [Reference Etienne and Faulkner2020] for additional advice and instructions for streaming game sessions). With options 2 and 3, however, the students will miss out on some of the interactive qualities of these resources.

As with all pedagogical tools, as instructors experiment with these activities in the classroom, additional challenges and opportunities will surely arise. This was the case in my own experience of teaching with AC: Origins.

CASE STUDY: ASSASSIN'S CREED: ORIGINS IN THE CLASSROOM

My decision to integrate AC: Origins into the classroom was born out of both a long-standing interest in playing digital games and a desire to engage my students in critical discussions with new media. I started by showing several of the Discovery Tour tours in a course on ancient Egyptian religion. I chose to play the game on a PlayStation 4 (PS4) console because it has a wireless controller that the students could pass around, which would offer better opportunities to share the immersive and interactive aspects. Because the PS4 has an HDMI connection I was able to plug it directly into the classroom computer system and display the game through projectors for the class members to watch together.

I was surprised by the success of this activity. Many of the students taking this course had little or no previous experience with ancient history, but most students did participate regularly. When discussing the game tours, however, several students who were usually quite reticent enthusiastically added to the discussion, and they brought in other experiences from AC: Origins and other games they had played. We discussed the differences between religious practice in Pharaonic and Greco-Roman history, and we questioned some of the details on mummification that were portrayed during the tour. I found that the previously reserved students participated more frequently in subsequent classes as well, and one noted a new interest in taking additional ancient history courses. In the anonymous course reviews, students noted that they enjoyed the integration of multiple media in class, and one specified the AC activity as a particular favorite.

I was subsequently asked by a colleague to give a guest lecture on the topic of digital games for a class on Egyptian and Near Eastern archaeology. I received permission to survey the students after the lecture. Based on the positive response in my religious studies class, I believed that archaeology students would also find the integration of digital games valuable, and a survey would help to test this assumption. This would also allow the students to voice any additional suggestions or concerns. Because I was not their regular instructor and would not be grading their work, I hoped that they would be encouraged to give honest feedback.

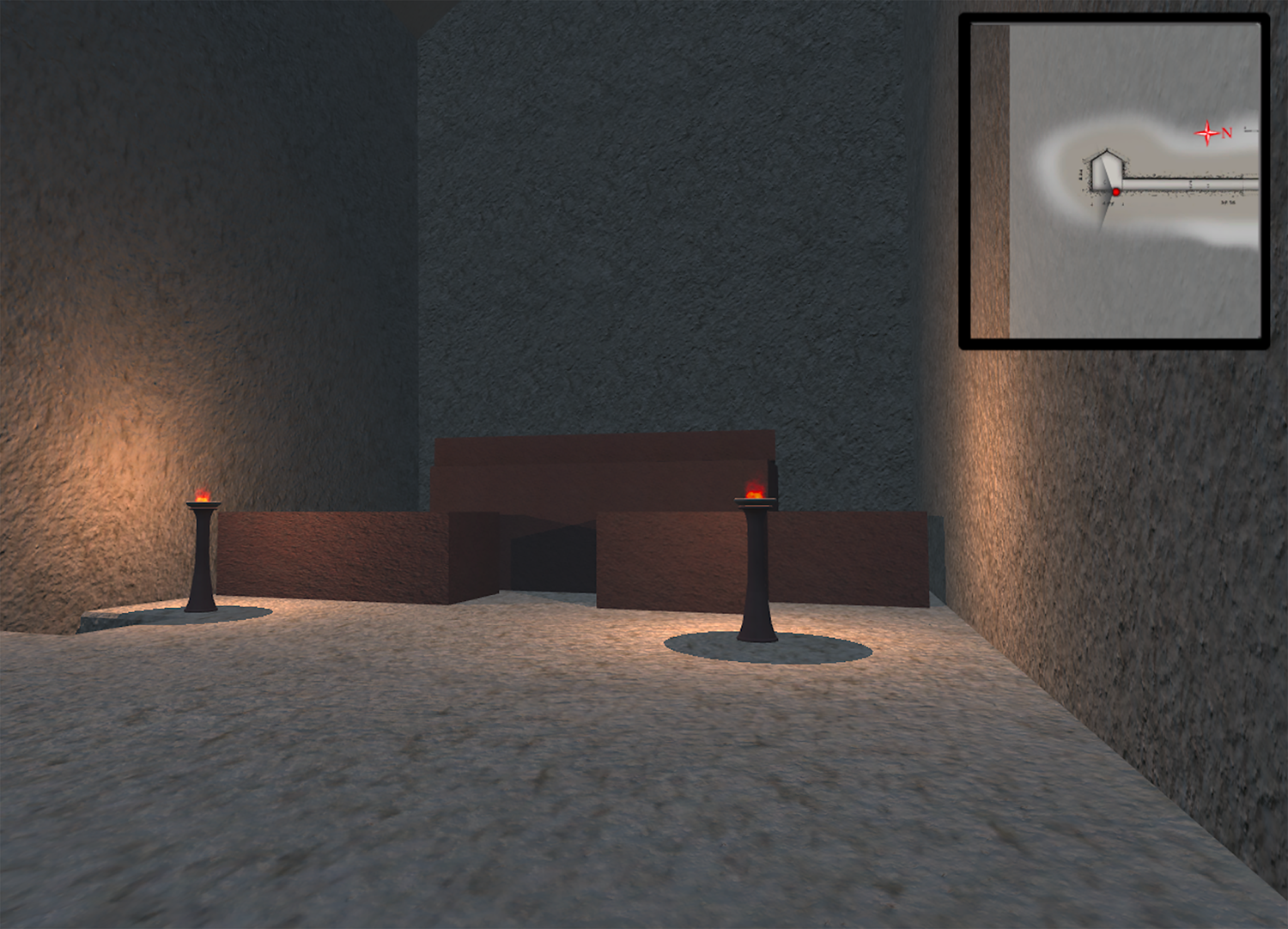

During the lecture, we discussed digital games and historical systems, including the previously mentioned work of Tara Jane Copplestone and the use of digital game design to explore the subjective nature of archaeological interpretations. The focus of the lecture, however, was on AC: Origins and the Giza pyramids. The students had already been introduced to the pyramids in previous classes, so they had some background knowledge. I began by leading the students through the in-game tour of the Giza plateau. We then focused on the pyramid of Khafre, a monument for which there is no curated voice-over tour in the Discovery Tour. After looking at a 2D diagram of the internal structure of the pyramid, along with photographs of the interior, I showed a comparison of two interactive digital models. I had created my own video walkthrough of the Khafre pyramid in AC: Origins (Figure 1) using an in-game recording and sharing option. I paired this with a screen recording of a similar route through Khafre's pyramid created by the online Digital Giza (2017) project by Harvard University (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Screenshot showing the interior of Khafre's pyramid from Assassin's Creed: Origins. (Taken by author.) © 2020 Ubisoft Entertainment. All Rights Reserved. Assassin’s Creed, Ubisoft, and the Ubisoft logo are registered or unregistered trademarks of Ubisoft Entertainment in the U.S. and/or other countries.

Figure 2. Screenshot showing the interior of Khafre's pyramid from Harvard's Digital Giza. (Taken by author. Courtesy of The Giza Project, Harvard University.)

After the reconstruction walk-throughs, I asked the students to consider which of the resources they found most effective: the 2D diagrams, photographs, or one of the two models. We then discussed the errors and additions to the game version, the benefits and drawbacks of each approach, and which audiences were likely to prefer the different options. After this, I gave the students the opportunity to take turns exploring the AC: Origins pyramids. While they were doing this, I handed out an optional and anonymous survey with the following open-ended question: “As students, do you think video games are / would be a valuable teaching tool? Why or why not?” I encouraged them to be as honest as possible, explaining that it would help with teaching decisions in the future.

Thirty-one students answered the survey. Every respondent believed that digital games offered some value for teaching. Twenty-five made reference to the ability of games to engage students in the subject matter, and two specified that it would help connect to interests outside of school work. One stated that such activities could “even trick you into learning.” Nine noted that games provided a more immersive, sensory experience of the past. Eight students brought up the need to talk about the historical inaccuracies in discussions. Of these, one noted that if the inaccuracies were not discussed, then playing historical games could actually be “harmful” to future learning. Three individuals also noted that digital games would only be valuable for teaching if they were selected appropriately, especially in relation to the amount of violence depicted. Three noted that they were more likely to remember details they interacted with in games. Two discussed the use of games to help learn about historical processes. One student noted that games would be very valuable, as long as students were given the opportunity to play them in the department, but added that students should not be asked to buy the games themselves. Finally, four students stated that although digital games were useful for inspiring discussions, they had doubts about using them for more in-depth projects. Of these, two respondents did not believe that games could help explore research questions better than written resources. Another noted, “I think most profs would be skeptical if I listed ‘Assassin's Creed’ in my works [cited] list.”

Although this was a simple and limited survey, I was impressed by the thoughtful responses. I had expected most students to agree that digital games would be a valuable teaching tool, but I was surprised that the class members were unanimous in their overall support. One student who mentioned never playing video games at home still agreed that they would be helpful to inspire discussions. I also found it interesting that students brought up both the need to discuss historical inaccuracies and the potential difficulties encountered by absorbing misinformation through popular media. The fact that a student also believed that instructors would be dismissive of digital games for student research reflects the prevalent attitudes noted above. I also found the comments regarding a lack of interest in in-depth projects based on digital games particularly interesting. These responses helped to guide the design of my subsequent lesson plans.

A few months after completing the survey, I taught a course on ancient Egyptian archaeology. During the term, I included many of the elements given in my previous lecture on digital games. This included tours from the Discovery Tour and a comparison of the interactive models of Khafre's pyramid by AC: Origins and Harvard's Digital Giza (2017). Again, we discussed the inaccuracies in the game version and the value of these different approaches for reconstructions. As with the previous survey, the students seemed to agree that the AC version may have been less accurate, but it was also more immersive and engaging. It can also be difficult to impress on students the immense time depth of ancient Egyptian history. AC: Origins is set in Greco-Roman Egypt, thousands of years after the pyramids were built. The Giza pyramids and associated monuments are therefore depicted partly covered in sand, and ancient looting tunnels have been incorporated into the models. Comparing these with the Digital Giza (2017) models, which show the pyramids in their newly completed state, was particularly effective. A few students came up after class to express how much they enjoyed the activity and to share a number of other archaeology-themed games with me. I then offered to let students come back to the department to explore other sites represented in the game. A few students chose to show up on their own time to explore several additional sites in the Discovery Tour for an hour. This again attests to how interested students are in exploring these popular representations, even with the violent elements of the game removed.

Given the success of the in-class discussions based around AC: Origins, I decided to incorporate a digital-game-based question as one of four options for the students’ term papers, noting also that students could design their own question if they so desired. I hoped that this would allow students enough flexibility to pick a topic that aligned with their research interests. Students who were uninterested in completing larger projects based on digital games would therefore be able to select another topic. The suggested options included writing an object biography, discussing specific archaeologists and their contribution to the field, and considering some of the different approaches to studying ancient Egyptian craft technologies. The final option asked, “Are digital reconstructions in popular media useful for archaeological projects or pedagogy?” The students were prompted to select a specific monument or site and compare the popular representations to plans and reconstructions from more traditional scholarly sources. They were asked to identify inconsistencies, suggest why different reconstruction options were chosen, and consider how/if the representation could be improved. They were also encouraged to supplement their written work with additional media.

When I initially discussed these different topics, a number of students expressed interest in the popular reconstruction option; however, when students submitted their papers, I was surprised to find that only 5 of my 48 students had selected this topic. Based on the class discussion and subsequent conversations, I have no doubt that many students found the topic engaging. I believe that students were too uncomfortable with the idea of working with new media and completing research based on their own analysis. In other courses in which my students were required to design simple online databases, I found a similar initial reticence to work with new resources and unfamiliar tools. Other scholars have described comparable experiences (Agbe-Davies et al. Reference Agbe-Davies, Galle, Hauser and Neiman2014:844). McCall (Reference McCall2011:20) even discusses how students working with digital games may feel “discomforted by the different approach to learning about the past,” especially if they have already mastered how to get good grades through traditional research methods (see also McCall Reference McCall2016:532–533). I had hoped that by showing my own comparison of the models of Khafre's pyramid and critiquing this media as a class, the students would feel confident in their ability to complete their own analysis; however, I believe I underestimated the discomfort that students would feel in writing a less traditional paper that integrated digital tools and required their own evaluation of the evidence.

To overcome these challenges in the future, I plan to require students to complete an additional, short group assignment focused on analyzing a specific construction within the AC: Origins universe. After the class lecture on digital games and Egyptian archaeology, which requires the completion of a selection of readings (Nielsen Reference Nielsen2017; Uricchio Reference Uricchio, Raessens and Goldstein2005), I will share a recorded video walk-through of a monument that all students will be able to access online. As groups of three to four students, they will then work together to analyze the monument and answer a selection of discussion questions either together in person or online through collaborative programs such as Google Docs. If the class is in person, the students will also be encouraged to book time in the department to explore the game as a group in order to benefit from interactive exploration. Students will then be asked to share their thoughts with their peers.

I hope that this additional, low-stakes group assignment will give students the space and time they need to become more comfortable engaging with these resources on a deeper level. This will allow them to experiment with original analysis, without risking a significant proportion of their grade. As noted previously, digital tools are becoming an increasingly important aspect of archaeology, and thinking about different ways that reconstructions can be used to engage different audiences may be useful for the students’ future careers. I also want to encourage students to gain experience adapting to less traditional assignments so that they might consider different approaches in their future research. Nevertheless, I still plan to give students additional research options for their larger term papers so that they have the opportunity to pursue topics that align with their individual interests. I hope that I will see more students selecting the popular media option—and more original analysis and thought in submitted papers as a whole—thanks to the incorporation of the short assignment. The short assignment and an updated term paper prompt for this topic have been included as Supplemental Text 1.

CONCLUSIONS

Digital games are an accessible and immediately available resource for teaching undergraduate archaeology courses—either in person or online. When integrated alongside traditional lectures and readings, they can inspire critical discussions of both archaeological processes and historic monuments and landscapes in popular media. In my own experience, I have found the Discovery Tour version of Assassin's Creed: Origins particularly useful for engaging students in discussions of popular historical reconstructions, and the long time depth of ancient Egyptian history. A limited sample survey of students involved in these discussions suggests that students themselves see these activities as valuable and engaging.

More in-depth projects involving digital games will require additional scaffolding and time as students adapt to these less traditional challenges. I believe, however, that it is important to encourage students to not only work with and critique new media but also experiment with new approaches to research. In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is becoming increasingly important to find new ways of utilizing the digital tools that are available for archaeological instruction to create captivating online and hybrid learning environments. Just as we need to challenge our students, instructors should also be prepared to constantly research and experiment with new media and new approaches to teaching.

Supplemental Material

To view supplemental material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2021.1.

Supplemental Text 1. Teaching materials.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Aris Politopoulos, Andrew Reinhard, Duncan MacLeod, and additional anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions for improving early drafts of this article. Thanks also to Karime Castillo for providing assistance with the Spanish abstract translation. A certificate of approval was obtained from the Behavioural Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia to discuss in-class experiences and the student survey data. No other permits were required.

Data Availability Statement

The results of the survey are in the Department of Asian Studies at the University of British Columbia, but they are not available per the terms of the human ethics application.