Introduction

Affecting an estimated 5–20% of the out-patient epilepsy population Reference Benbadis and Hauser(1), non-epileptic attacks are clinical events in which changes in movement, sensation or experience resemble the changes occurring during epileptic attacks. These non-epileptic attacks, however, do not arise from the specific central nervous system dysfunction underlying epilepsy. Non-epileptic attacks may be physiological or functional in nature. The former may have underlying causes that may include transient ischemic attacks, narcolepsy, hemiplegic migraine, paroxysmal vertigo, cardiac arrhythmia, hypoglycaemia or syncope Reference Aldenkamp and Mulder(2). Functional non-epileptic attacks (FNEA), on the other hand, are psychogenic in aetiology and represent approximately 90% of the non-epileptic attacks. FNEA may arise from the accumulation of stressful, negative life events Reference Tojek, Lumley, Barkley, Mahr and Thomas(3), especially in patients who are not conscious of Reference Bowman(4), or able to speak about Reference Griffith, Polles and Griffith(5), their negative emotions. Acute anxiety disorders (e.g. panic disorder), depressive disorders, somatoform disorders, conversion/dissociative disorders and personality disorders have been reported to be aetiologically linked to FNEA Reference Bowman(4,Reference Bowman6). Traumatic events, physical, sexual and childhood psychological abuse have also been claimed to be associated with the development of FNEA (Reference Bowman6–Reference Salmon, Al-Marzooqi, Baker and Reilly8), although this remains controversial.

FNEA is commonly encountered in neurological settings, often without associated somatoform spectrum disorders. In this it tends to differ from other conversion/dissociative disorders. Moreover, FNEA is episodic, panic constitutes a common trigger and clinical experience suggests that outcome for this patient group may be better than other somatoform spectrum disorders. Therefore, this paper will focus on FNEA, specifically.

Several different psychological treatment approaches for FNEA are currently in use, which reflects lack of consensus about the most useful intervention. Moreover, outcomes for this condition remain often poor, with considerable economic and personal costs. Thus, in order to guide clinical practice and future research in this area, we have performed a systematic review of the published literature on the psychological treatments of FNEA.

Background

FNEA were first described by the ancient Greeks, and since that time a range of treatments for FNEA has been tried. LaFrance and Devinsky Reference LaFrance and Devinsky(9) describe some of the treatments used in the 18th and 19th centuries. These include use of physical exercise by Mandeville in a case of ‘hysterical seizures' and Gower's use of aversive therapies such as electric shock or blocking the nose and mouth. The French neurologist, Charcot, used physiological treatments, including ovarian compression, and also experimented with the effects of suggestion upon hysterical attacks Reference Krumholz(10).

The early 20th century saw the development of two opposing views of FNEA Reference Trimble(11). On one hand, numerous authors have distinguished between FNEA and epilepsy. On the other hand, Freud, followed by Clark in the 1920s and Krapf in the late 1950s, emphasised the connection between hysteria and epilepsy. Freud also noted the influence of suggestion upon the course of FNEA. Unlike Charcot, however, he concluded that hysterical attacks were not organic neurological disorders, but were emotional in nature, resulting from repressed energies or drives situated in the unconscious mind. As the split between psychiatry and neurology widened, epilepsy came almost exclusively into the domain of neurology, while treatment of ‘hysteria’ came into that of psychiatry. This dichotomy in clinical service provision perpetuated the dearth of studies looking into appropriate treatments for FNEA.

Today FNEA are classified within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition text revision (12) as a subtype of conversion disorder within the group of somatoform disorders. However, this is considered unsatisfactory as there is recognition that FNEA may occur as a result of a range underlying psychiatric processes. They may be associated with conditions such as anxiety disorders (including post-traumatic stress disorder), depression, somatoform disorders or dissociative disorders, although the demarcation between these conditions is often not clear cut. Moreover, as Bowman Reference Bowman(4) warns, FNEA may in fact be misdiagnosed panic attacks, dissociative trance episodes or flashbacks of trauma. A number of other classifications have been proposed for FNEA, none of which is currently universally accepted (Reference Bowman4,Reference Krumholz10,Reference Alper, Devinsky, Perrine, Vazquez and Luciano13–Reference van Rijckevorsel, Lennox, Fouchet, Indriets and Sylin15).

Nomenclature for FNEA also continues to be subject to debate. ‘Non-epileptic seizures', ‘psychogenic seizures', ‘hysterical seizures' and ‘pseudoseizures’ are a few of the names that have been used. Many clinicians today feel that these terms are, for the most part, inaccurate, as well as carrying pejorative connotations. Research has shown that patients find ‘functional’ to be the most acceptable term to describe disorders of non-organic aetiology Reference Stone, Wojcik and Durrance(16). For this reason, we prefer FNEA as the term to describe this condition. It is important to emphasise that, although not caused by neurological dysfunction, it would be an error to think that these attacks are ‘fake’ and FNEA is not a ‘real’ disorder.

The personal, social and economic impact of FNEA can be devastating. Many FNEA patients are unable to pursue education or employment, and thus represent a considerable drain on family or public resources. They make repeated visits to emergency and other medical services, often receiving inappropriate and sometimes fatal medical interventions Reference Reuber, Baker, Gill, Smith and Chadwick(17), running at an estimated annual cost of $110–920 million, in the USA alone Reference Martin, Gilliam, Kilgore, Faught and Kuzneicky(18). In another study, follow-up at 1 year showed that patients of control physicians had mean health care charges 21% higher than experimental condition physicians who were provided with treatment recommendations Reference Rost, Kashner and Smith(19). Thus ensuring the best treatment for FNEA is a matter of considerable importance.

One theme in recent literature is that the choice of treatment approach should be based upon the underlying or comorbid psychiatric condition Reference Betts and Boden(14). However, in practice, this is not always straightforward because of the lack of strict symptomatic demarcation between these conditions. Moreover, not all FNEA patients present with psychiatric co-morbidity Reference Jawad, Jamil, Clarke, Lewis, Whitecross and Richens(20). For this reason, therapeutic interventions are most often tailored to the needs of the individual patient and designed to address more than a single problem. Although reports of treatment programmes tend to group approaches into categories, these distinctions frequently reflect the clinician's theoretical orientation rather than mutually exclusive, rigorously operational differences in actual client work Reference Williams, Spiegel and Mostofsky(21).

Cognitive behavioural, cognitive, behavioural, psychodynamic, systemic, hypnosis and psychoeducational interventions (and various combinations of these) have been used in individual and group therapy settings. Psychopharmacology has been used as an adjunct, as well as with patients who refuse talking therapy. The literature to date provides the beginnings of an empirical foundation to guide treatment decisions. However, choice of specific treatment modality has depended as much on the theoretical leanings of the clinician, as upon underlying or comorbid conditions. A systematic review of the literature is thus relevant and timely for moving the treatment of this group of patients forward.

Methods

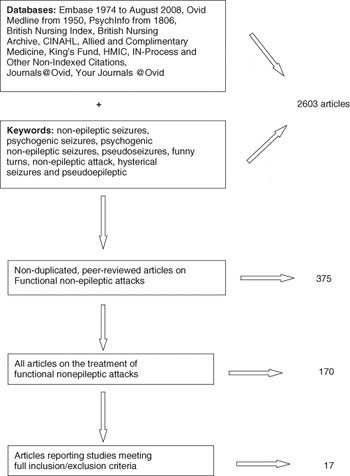

A comprehensive literature search of the following electronic databases was conducted: Embase from 1974; Medline from 1950; PsychINFO from 1806; British Nursing Index from 1994; Allied and Contemporary Medicine from 1985; CINAHL from 1982; Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC); King's Fund from 1979; In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations; Journals@Ovid Full Text and Your Journals @Ovid, all through August 2008. Key words: non-epileptic seizures; psychogenic seizures; psychogenic non-epileptic seizures; pseudoseizures; funny turns; non-epileptic attacks; hysterical seizures; and pseudoepileptic were used. From the combined lists thus obtained, duplicates were eliminated. Unpublished studies, including conference proceeding abstracts were included, but only if a full peer-reviewed published version of the same study could not be found. If same patient sample seemed to be described in two overlapping studies, then the study with the smaller sample was excluded. Reference sections of relevant articles and reviews were examined to ensure a comprehensive review of available literature.

Studies were included when consensus was reached between two authors (DG and NA) that they met the inclusion criteria. To be included in the systematic review, papers had to describe one or more psychological treatment modalities for FNEA and to have been published in English language peer-reviewed journal. Studies of patients having the specific diagnosis of FNEA (rather than the more general conversion disorder or somatisation disorder) were retained. Studies were excluded if they used samples of patients with epileptic or other organic seizures, or with comorbid epilepsy, unless patients with these conditions constituted a control sample. Studies of patients with learning disabilities were also excluded. Reports were then categorised according to level and type of evidence. Single case studies, opinion papers, reviews, books, book chapters, dissertations and non-English language articles were excluded.

Outcome data focusing on seizure frequency were extracted. In order to quantitatively compare the results between the studies, outcomes were categorised into four groups: attack free; partial reduction; no change or worse. In cases where data were not available, intention to treat analysis was applied; missing data were grouped with the least favourable outcome category (worse).

Results

Figure 1 summarises the results of the systematic literature search. 170 articles were identified, which covered psychological treatment of FNEA. These encompassed 10 treatment approaches: cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), behavioural, psychodynamic, cognitive, paradoxicalFootnote 1, family, group, hypnosis or suggestion, ‘presenting the diagnosis' and mixed/other interventions.

Fig. 1 Flowchart of results systematic literature search for treatment of functional non-epileptic attacks.

Full application of the inclusion criteria yielded only 17 studies, the majority of the published literature being single case reports, opinion and non-systematic review articles. Of these 17 papers, four are conference abstracts for which no subsequently published peer-reviewed articles have been found. Characteristics of the 17 studies are summarised in Table 1. We came across only one randomised controlled trial (RCT) that looked at the treatment of FNEA specifically. Other study designs that have been used include open trials (nine studies) and case series (six).

Table 1 Studies of treatments for functional non-epileptic attacks

FNEA, functional non-epileptic attacks; RCT, randomised controlled trial; EEG, electroencephalography; vEEG, video electroencephalography; EMDR, eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing; CBT, cognitive behaviour therapy; PT, placebo therapy; N, total participants; T, treatment condition; C, control condition; AF, attack free; PR, partial reduction; NC, no change; W, worse; AEDs, anti-epileptic drugs.

* Modification of Shen et al. (1990), described as a ‘psychoeducational presentation of diagnosis'. # Conference abstract. No subsequent publication.

For purposes of consistency, we have used the term FNEA for our patient description. Individual authors have used other terms

A recent Cochrane review Reference Brooks, Baker, Goodfellow, Bodde and Aldenkamp(39) has flagged two other RCTs that tested hypnosis-based treatment. However, these RCTs tested treatments for conversion disorder or somatisation disorder in general and do not provide specific data on FNEA. As such, these two studies did not meet our inclusion criteria and were excluded.

Seven treatment categories were studied in the papers included in this review (see Table 1). Mixed modality interventions are the best represented, with seven studies using varied designs. Another five studies tested ‘presenting the diagnosis'. One RCT tested paradoxical therapy. One open trial tested CBT. Behavioural therapy, individual psychoeducation and group psychoeducation have also been explored in one study each.

A wide diversity of outcome measures has been used; the most commonly reported being attack frequency. This is also likely to be relevant in terms of individual disability, social and healthcare costs. Thus, we have focused on this measure for comparison across studies and treatment modalities. Table 2 describes six relevant treatment studies that were excluded as attack frequency outcome figures were not provided, which would have made it impossible to extract data for comparison.

Table 2 Relevant Function Non-Epileptic Attack treatment studies subsequently excluded

N, total participants; T, treatment condition; C, control condition; PDT, Psychodynamic Group Therapy; CBT, Cognitive Behaviour Group Therapy; #, conference abstract.

FNEA diagnoses were made or confirmed using video electroencephalographic (vEEG) telemetry in at least 283 of the 452 total cases. This diagnostic method has been used more consistently as the technology has become more widely available and affordable. Other diagnostic methods included ictal EEG, inter-ictal EEG and clinical impression.

The majority of studies examined small population samples. Of the 17 studies, 7 included 30 or more participants and only 4 had N of 50 or more participants. The study of paradoxical therapy had 30 FNEA patients randomly divided between experimental and control groups. Two open trial investigations of ‘presenting the diagnosis' modality used control groups, which were non-randomised. One of these Reference Farias, Thieman and Alsaadi(32) compared outcomes for FNEA patients and epilepsy patients following the presentation of the diagnosis. Vojvodic et al. Reference Vojvodic, Ristic, Sokic, Jankovic and Sindjelic(34) compared two different methods of presenting the diagnosis to two groups of FNEA patients.

Study outcomes for adult treatment condition FNEA patients (measured as attack frequency) were compared and are presented in Table 3. Paediatric studies, all of which examined mixed modality treatments, are summarised in Table 4.

Table 3 Overview of functional non-epileptic attack frequency outcomes for adults

DO = drop-out; LFU = lost to follow-up; T = treatment condition; C = Control condition

Table 4 Overview of paediatric functional non-epileptic attack frequency outcomes

DO = drop-out; LFU = lost to follow-up

Duration of treatment and follow-up was poorly reported and was widely variable in length. The shortest period was 24 h (for an investigation of ‘presenting the diagnosis') and the longest was 5 years for a case series that looked at mixed modality treatments.

Discussion

Results from this systematic review suggest that, in terms of attack reduction, psychotherapeutic interventions may be helpful for FNEA patients. However, a number of methodological issues should be highlighted in order to put these results into perspective. The main difficulty we encountered in drawing together information for this review stems from the heterogeneity of studies undertaken. Variation in study design, numbers of studies per treatment modality, population sample sizes and inclusion of control groups, duration of follow-up and standardisation of outcome measures compromise the confidence with which we may make comparisons between treatment modalities. Within group differences were also found in the operationalisation of treatment modalities from one study to another. The most homogeneous group was composed of those studies investigating ‘presenting the diagnosis', largely thanks to the early availability of a detailed protocol Reference Shen, Bowman and Markand(30). In contrast, mixed modality treatment studies examined the effects of widely varied combinations of the 10 treatment categories we identified in the overall literature base. Moreover, with the exceptions of those studies based on the Shen et al. protocol Reference Shen, Bowman and Markand(30) and of the CBT study Reference Goldstein, Deale, Mitchell-O’Malley, Toone and Mellers(35), it is not clear that the remaining studies examined manualised therapeutic programmes. Few of the other papers describe the details of the interventions studied. It cannot, therefore, be ascertained whether patients within each study received identical treatment.

Finally, it is difficult, if not impossible, to evaluate any of these modalities independent of other overlapping or concurrent therapeutic influences Reference Williams, Spiegel and Mostofsky(21). For all of these reasons, we believe that meta-analysis of the data could be misleading. Instead, we have presented summary data, with some synthesis between studies where possible. Of note, because we interpreted unreported outcomes as ‘worse’, the outcome data in Table 3 represent the most conservative efficacy estimate.

The only RCT that met our inclusion criteria suggests that paradoxical therapy is more effective than treatment with anxiolytics Reference Ataoglu, Ozectin, Icmeli and Ozbulut(22). However, the numbers are small, and whereas the control group received medication as outpatients, those in the experimental group were treated as in-patients and received considerable attention from the treating team. Whether the reported outcomes truly reflect efficacy of the paradoxical therapy itself is uncertain.

Mixed modality interventions have been the most widely studied and appear to be relatively successful across adult and paediatric populations, with between 41 and 75% of patients, respectively, showing complete remission of their attacks. This might be expected. As Williams et al. Reference Williams, Spiegel and Mostofsky(21) point out, the environmental and intrapsychic triggers of attacks are often complex and multidimensional, so that treatment programmes frequently need to be designed to address more than one single problem. While mixed or eclectic treatment approaches may be difficult to operationalise and compare across different studies, they may be closer to the clinical practice and be more successful because of their individualised focus. This will need further attention in the future research.

It would appear that two sessions of individual psychoeducation were helpful, with 58% of patients reported to be attack free at 12 months following the diagnosis Reference So, Bennett and Smith(37). A 10-session group psychoeducation programme, however, did not fare so well, with only 14% of patients achieving attack remission at the end of treatment Reference Zaroff, Myers, Barr, Luciano and Devinsky(38). This should be interpreted cautiously as only 7 patients completed the group programme, in contrast to 71 in the individual study. In a relatively large study of patients previously diagnosed with epilepsy, then correctly identified as having FNEA Reference Carton, Thompson and Duncan(46), the majority showed a lack of clear understanding of the new diagnosis. Of respondents, 38% reported feeling confused, not least because of the lack of obvious temporal relationship between stressful events and the occurrence of FNEA. The authors speculate that this confusion may be because of inadequate or inappropriately delivered information at the time of diagnosis. In the Shen et al. Reference Shen, Bowman and Markand(30), study all patients accepted the diagnosis. Of these, 50% were attack free at follow-up, whereas the other 50% suffered from fewer attacks than before the intervention. Likewise, Wilder et al. Reference Wilder, Marquez and Farias(33) found that patients who ‘responded’ to treatment were significantly more likely to have believed the diagnosis than those who did not respond to the intervention. Hence, enhancing patient understanding and acceptance of diagnosis through psychoeducation may be an important therapeutic goal.

‘Presenting the diagnosis' has been commonly studied and, in many ways, effectively represents a single session of psychoeducation. This modality similarly gave good overall results, with 45% of open trial patients and 50% case series patients achieving attack remission. In these studies, 38 and 50% of patients respectively also benefited in terms of partial reductions of attack activity.

It is perhaps of interest that a higher percentage of patients became attack free following these single session interventions compared with the Goldstein et al. Reference Goldstein, Deale, Mitchell-O’Malley, Toone and Mellers(35) patients who received 12 sessions of CBT (25%). It is likely, however, that in addition to the relatively small numbers and different entry criteria, differing durations of follow-up may be skewing the results.

The claim has been made that children tend to have better outcomes than adults, in terms of attack remission Reference Gudmundsson, Prendergast, Foreman and OxCowley(27). Collective results from studies reviewed here appear to support this claim (72 vs. 46% respectively), although methodological issues limit the confidence with which this can be concluded. Wyllie et al. Reference Wyllie, Friedman, Lüders, Morris, Rothner and Turnbull(45) have also examined this question, although not within the framework of a systematic investigation of treatment outcomes. 78% of their paediatric patients received counselling, as did 50% of the adults. Although the authors report that this factor was not associated with outcome, they did not provide attack frequency results for these patients. They do, however, discuss two possible explanations for their findings. One suggestion is that different psychological mechanisms may be associated with different ages at onset. Another possibility is that younger patients usually have shorter duration of FNEA before definitive diagnosis.

Conclusions

A large number of FNEA intervention studies have been reported in the literature, representing the beginnings of an empirical foundation to guide treatment. However, the quality of the current evidence base leaves much to be desired. Nonetheless, the emerging theme apparent from this systematic review is that a range of psychological treatments can be effective in this patient population.

Treatments that might hold the best promise in the future include psychoeducational approaches including presenting the diagnosis and mixed modality or eclectic treatment approaches. Paradoxical therapy and other behavioural approaches perhaps deserve further study. The role of CBT for this patient group has been relatively understudied, but is not well supported by the little information we have.

The heterogeneous nature of this patient group may mean that a combination of treatments based on the underlying problems may be required. Traditional CBT approaches may be less successful in this patient group than a combination of treatments incorporating CBT principles. One such combination could include presentation of diagnosis, further psychoeducation and subsequent individualised treatment using different psychotherapeutic techniques based on underlying psychological issues. However, this will need to be studied systematically in the future.

Any future research will need to be based on large multi-centric RCTs as a cornerstone. There is an urgent need for consensus on more clinically relevant outcome measures. Figure 2 outlines possible outcome measures that may be used more consistently in the future. An adequate duration of follow-up, which ideally should be at least 1 year will need to be built in. Balance will need to be struck between eclectic and modular strategies to individualise the treatment versus operationalised and manualised treatment to ensure uniformity. While empirical foundations are beginning to be laid, there is a long way to go till a clear structure is visible.

Fig. 2 Alternative outcome measures following psychological treatment for FNEA.