Wilson's disease (WD) is an autosomal recessive inherited disorder of copper metabolism due to mutations in the ATP7B gene. The disease usually manifests in the first or second decade of life, either as a liver disease or with neuropsychiatric disturbances.

We present a 45-year-old female with general anxiety disorder as a first manifestation of WD with profound abnormalities on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

A 45-year-old female was admitted to Psychiatry Department because of severe anxiety and fear of death. On examination she was oriented in time and place, restless and had a feeling of keyed-up, she was easily fatigued, had difficulty concentrating, showed increased irritability and muscle tension and had sleep disturbance. Her family members and co-workers noted in the couple of previous months that she was very irritable, had poor concentration and was forgetful. Standard laboratory findings revealed leucopenia and thrombocytopenia. Abdominal ultrasound showed diffuse hypoechogen nodules in the liver. Because she was noted to have short-term memory disturbance, brain MRI was performed to reveal T2 hyperintensities in the medulla, pons and both thalami.

On admission to our department, neurological examination showed that she was oriented in time and place, her minimental state examination (MMSE) was 24/30 (−2 points on short term memory and −4 points on serial subtraction), the 3′ paced auditory serial addition test (PASAT) was 17/60, the clock drawing test was 8/10 and face recognition test was 18 in the first 90 s (5 s per face), and in 5 min was 51 (6 s per face) but she could not finish the test till the end. Cranial nerve examination was normal except saccadic pursuit eye movements and positive Kaiser-Fleischer rings bilateraly. She had brisk reflexes (3+), negative Babinski and truncal ataxia.

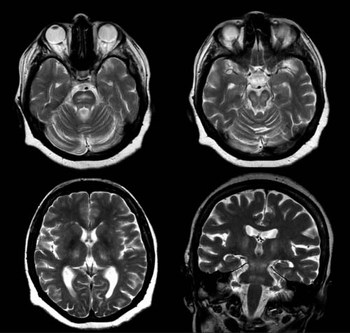

Laboratory examination revealed leucopenia, elevated liver enzymes, serum copper levels and ceruplasmin levels were normal, but 24-h urin copper level was elevated. Repeated brain MRI showed T2 hyperintensities in the pons, crura cerebri and thalami bilaterally, which were hypointense in T1 sequences and did not show diffusion restriction (Fig. 1). Multi-sliced computed tomography of the liver showed numerous hypodense zones without contrast enhancemet, dilated portal and lineal veins and tortuous collateral veins on the gastric greater curvature. Liver biopsy was performed to show macrovesicular steatosis with vacuolated hepatocytes nuclei. Copper level in the dry liver was 806 μg/g (pathologic values >90).

Fig. 1 Magnetic resonance imaging and T2-weighted images. Hyperintensities are present in pons, mesencephalon with relative sparring of supstantia nigra, and bilaterally in thalami. Pronounced atrophy of brain parenchima is more evident in brain stem and cerebellum.

The patient was started on penicillamin therapy (initial dose of 300 mg 2 times per day (BID) with gradual increase of the dose). Upon treatment, she developed transient tremor of the right hand. On follow up she had no more psychiatric symptoms, but still had cognitive decline.

It was generally believed that WD does not occur in patients older than 40 years. However, recently published series suggested that it may become symptomatic in patients older than 40 years Reference Ferenci, Czonkowska and Merle(1). Approximately 3.8% of WD patients present after age of 40, and most of them have neuropsychiatric symptoms Reference Ferenci, Czonkowska and Merle(1). It is interesting that majority of these patients come from Eastern and Central European countries, the basis of this discrepancy still remains unclear.

Psychiatric manifestations of WD may occur in any stage of the disease. The key psychiatric symptoms are excessive talkativeness, aggressive behavior, loss of interest in the surroundings, and abusiveness, and some of these patients fulfil the diagnostic criteria for syndromic psychiatric illnesses like bipolar affective disorder, major depression or dysthymia Reference Shanmugiah, Sinha and Taly(2). In one prospective study, it was noted that two-thirds of all WD patients had psychiatric symptoms at the time of diagnosis Reference Akil and Brewer(3). However, true psychiatric syndromes as a initial manifestation of WD have seldom been reported Reference Machado, Deguti, Caixeta, Spitz, Lucato and Barbosa(4,Reference Srinivas, Sinha and Taly5). The cause of psychiatric symptoms in WD patients is still unclear. Some authors have found deficit of D2 receptors in the basal ganglia Reference Keller, Torta, Lagget, Crasto and Bergamasco(6). On the other hand, brain MRI abnormalities which are encountered in WD patients can also, in some extent, explain psychiatric and cognitive symptoms. Our patient had bithalamic T2 hyperintesities on brain MRI, and it is known that bithalamic lesions can produce psychiatric and cognitive symptoms, because thalamus have connections with frontal lobes, limbic system and activating reticular formation of the brainstem which are directly related to the mechanisms of behavioural control, emotions and memory Reference Habek, Brinar, Mubrin, Barun and Zarković(7,Reference Carrera and Bogousslavsky8). Even treated patients have significant deviations in personality traits, especially in aggressivity-hostility-related scales and psychix anxiety Reference Portala, Levander, Westermark, Ekselius and Von Knorring(9).

MRI studies in WD have shown numerous abnormalities. The most frequent signal alterations are encountered in putamen and caudate (80%), globus pallidus (60%), deep cerebral whitematter (53%), brainstem (47%), thalamus (40%) and cerebral cortex (40%) Reference Page, Davie and MacManus(10). Rarely, basal ganglia and thalamic lesions are hypointense on T1-weighted sequences Reference Page, Davie and MacManus(10). MRI spectroscopy studies have shown specific reduction of N-acetylaspartate (NAA) in patients with neuropsychiatric manifestations Reference Das, Misra and Kalita(11). These morphological changes are located in the regions responsible for emotion, memory and other cognitive function, and thus could, at least partly, explain the symptoms.

In conclusion, patients older than 40 years with mainly psychiatric symptoms should be screened for WD, even if there are no other neurological and systemic symptoms. Slit lamp examination for Kaiser-Fleischer rings can be very useful and is easy to perform. This is of outmost importance, because early treatment is life saving.