Significant outcomes

Decreased CSF Aß42 levels were associated with impaired cognitive performance.

Intrinsic functional connectivity was not altered in mild cognitive impairment patients.

CSF biomarkers seem to be more closely related to cognitive function than resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging.

Limitations

Since there are no longitudinal data available, the prognostic value of the biomarkers assessed in this study is limited.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s Dementia (AD) is a neurodegenerative condition that results in a progressive clinical syndrome that is characterised by an impairment in memory and other cognitive functions (Hodges, Reference Hodges2006). Amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is considered as the prodromal phase of AD (Dubois & Albert, Reference Dubois and Albert2004). This prodromal phase is characterised by the accumulation of beta-amyloid (Aß) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles that lead to neuronal death and deteriorating neurocognitive function (Jack & Holtzman, Reference Jack and Holtzman2013). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of these neurodegenerative processes are the 42 amino acid form of amyloid protein (Aß42), total tau (T-tau) and hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) (Andreasen & Blennow, Reference Andreasen and Blennow2005). The effect of these three CSF biomarkers on neurocognitive function has been investigated by several studies. It has been shown that lower levels of cerebral Aß42 are closely associated with impaired memory performance in MCI patients (Hedden et al., Reference Hedden, Mormino, Amariglio, Younger, Schultz, Becker, Buckner, Johnson, Sperling and Rentz2012; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Lim, Abbott, Galluzzi, Marizzoni, Babiloni, Albani, Bartres-Faz, Didic, Farotti, Parnetti, Salvadori, Muller, Forloni, Girtler, Hensch, Jovicich, Leeuwis, Marra, Molinuevo, Nobili, Pariente, Payoux, Ranjeva, Rolandi, Rossini, Schonknecht, Soricelli, Tsolaki, Visser, Wiltfang, Richardson, Bordet, Blin, Frisoni and Pharmacog2017). Elevated levels of total tau and hyperphosphorylated tau seem to be related to impaired memory (Malpas et al., Reference Malpas, Saling, Velakoulis, Desmond and O’brien2015; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Lim, Abbott, Galluzzi, Marizzoni, Babiloni, Albani, Bartres-Faz, Didic, Farotti, Parnetti, Salvadori, Muller, Forloni, Girtler, Hensch, Jovicich, Leeuwis, Marra, Molinuevo, Nobili, Pariente, Payoux, Ranjeva, Rolandi, Rossini, Schonknecht, Soricelli, Tsolaki, Visser, Wiltfang, Richardson, Bordet, Blin, Frisoni and Pharmacog2017) and executive function (Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Lim, Abbott, Galluzzi, Marizzoni, Babiloni, Albani, Bartres-Faz, Didic, Farotti, Parnetti, Salvadori, Muller, Forloni, Girtler, Hensch, Jovicich, Leeuwis, Marra, Molinuevo, Nobili, Pariente, Payoux, Ranjeva, Rolandi, Rossini, Schonknecht, Soricelli, Tsolaki, Visser, Wiltfang, Richardson, Bordet, Blin, Frisoni and Pharmacog2017).

Aß42, total tau and hyperphosphorylated tau have been proven useful in distinguishing MCI patients with a high risk of conversion to AD from those with a low risk (Riemenschneider et al., Reference Riemenschneider, Lautenschlager, Wagenpfeil, Diehl, Drzezga and Kurz2002; Zetterberg et al., Reference Zetterberg, Wahlund and Blennow2003). Additionally to the well-established CSF biomarkers, resting state connectivity has also been proposed as a possible biomarker for the prodromal stages of AD (Sorg et al., Reference Sorg, Riedl, Muhlau, Calhoun, Eichele, Laer, Drzezga, Forstl, Kurz, Zimmer and Wohlschlager2007). Resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) allows analysing regional interactions of brain regions in a resting state when no task is performed. Previous rs-fMRI studies have shown that functional connectivity is already altered in the early stage of AD (Greicius et al., Reference Greicius, Srivastava, Reiss and Menon2004; Rombouts et al., Reference Rombouts, Damoiseaux, Goekoop, Barkhof, Scheltens, Smith and Beckmann2009) as well as in MCI patients (Ishii et al., Reference Ishii, Mori, Hirono and Mori2003). One of the most investigated resting state networks is the default mode network (DMN). The DMN is a set of interacting brain regions that are typically active during rest, while being deactivated when engaged in a cognitively demanding task (Raichle et al., Reference Raichle, Macleod, Snyder, Powers, Gusnard and Shulman2001). Evidence from functional neuroimaging studies suggests substantial topographic overlap between the DMN and networks underpinning episodic memory processing (Buckner et al., Reference Buckner, Snyder, Shannon, Larossa, Sachs, Fotenos, Sheline, Klunk, Mathis, Morris and Mintun2005; Spreng et al., Reference Spreng, Mar and Kim2009; Sestieri et al., Reference Sestieri, Corbetta, Romani and Shulman2011). Activity in the DMN during resting state seems to predict episodic memory performance in healthy adults (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Bossmann, Schiffhauer, Jordan and Immordino-Yang2012) and in neurological patients (McCormick et al., Reference Mccormick, Quraan, Cohn, Valiante and Mcandrews2013). Besides their role for episodic memory processing, the regions of the DMN also show a striking overlap with regions with high amyloid depositions (Buckner et al., Reference Buckner, Snyder, Shannon, Larossa, Sachs, Fotenos, Sheline, Klunk, Mathis, Morris and Mintun2005; Sperling et al., Reference Sperling, Laviolette, O’keefe, O’brien, Rentz, Pihlajamaki, Marshall, Hyman, Selkoe, Hedden, Buckner, Becker and Johnson2009; Sheline et al., Reference Sheline, Raichle, Snyder, Morris, Head, Wang and Mintun2010). Aß42 load has been proposed to have a direct effect on functional connectivity. Clinically healthy subjects with high Aß42 load have been shown to have decreased connectivity in the DMN (Sperling et al., Reference Sperling, Laviolette, O’keefe, O’brien, Rentz, Pihlajamaki, Marshall, Hyman, Selkoe, Hedden, Buckner, Becker and Johnson2009). This has also been shown in patients with MCI (Drzezga et al., Reference Drzezga, Becker, Van Dijk, Sreenivasan, Talukdar, Sullivan, Schultz, Sepulcre, Putcha, Greve, Johnson and Sperling2011). On the contrary, Adriaanse et al. (Reference Adriaanse, Sanz-Arigita, Binnewijzend, Ossenkoppele, Tolboom, Van Assema, Wink, Boellaard, Yaqub, Windhorst, Van Der Flier, Scheltens, Lammertsma, Rombouts, Barkhof and Van Berckel2014) did not find an association between amyloid load and DMN connectivity in healthy elderly, MCI patients and AD patients. Thus, the role of Aß42 load in the brain on DMN connectivity is still unclear. For the current study, we investigated alterations in intrinsic functional connectivity associated with MCI. Furthermore, we investigated the association between the three major CSF biomarkers (Aß42, total tau and hyperphosphorylated tau) and cognitive function in MCI patients. We hypothesised that lower concentrations of CSF Aß42 and higher concentrations of CSF total tau (T-tau) and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) would be associated with greater cognitive decline and that DMN connectivity would be altered in MCI patients.

Materials and methods

Participants

We examined a subset of 68 participants (MCI group: mean age 66.9 ± 7.1 years; control group: mean age 66.4 ± 4.1 years) drawn from a larger cohort of 250 subjects. The larger cohort includes 117 young (age 20–39 years) and 153 old participants (age 55–80 years) without any history of neurological or psychiatric disease. Participants were recruited through various advertisements in local and national newspapers. MCI patients were recruited via cooperation with the Memory Clinic at Goethe University Frankfurt am Main. The selection of the 68 participants analysed here was based on the cognitive status. 38 participants fulfilling the diagnosis of an MCI were selected together with 30 cognitively healthy controls, matched for age and education. The local ethics committee of Goethe University Frankfurt approved the study. All subjects declared that they understood the experimental procedure and signed a written informed consent. The study was undertaken in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki; Rickham, Reference Rickham1964). The CSF samples were collected by lumbar puncture. The samples were stored in polypropylene tubes at −80°C until analyses. The measurement of CSF, Aß42, T-tau and p-tau was done by the laboratory of Dr. Fenner and colleagues. Commercially available colorimetric enzyme immunoassays (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium) were used for the quantitative determination of Aß42, T-tau and p-tau following the manufacturer’s protocol. The measurements were done blinded to the diagnosis. Verbal learning and memory were assessed using the German Version of the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT, Delis et al., Reference Delis, Kramer, Kaplan and Ober1987; German version by Niemann et al., Reference Niemann, Sturm, Thöne-Otto and Willmes2008). Additionally, attention was assessed using the Trail Making Test A (Spreen & Strauss, Reference Spreen and Strauss1998). The CERAD–NP (Consortium to Establish a Registry for AD) (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Mohs, Rogers, Fillenbaum and Heyman1988) was done to capture cognitive decline. MCI was diagnosed, if participants met the following criteria: (1) subjective memory impairment and (2) a score of at least 1.5 standard deviations below the norm (adjusted for sex, age and education) in any of the CERAD’s subtests. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the German Version of the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1996, German adaptation by Hautzinger et al., Reference Hautzinger, Keller and Kühner2006). Each participant was assessed by an experienced psychiatrist or a psychologist to rule out concurrent causes for cognitive deficits such as sleep disorders, depression or other psychiatric disorders (e.g. alcoholism and psychosis).

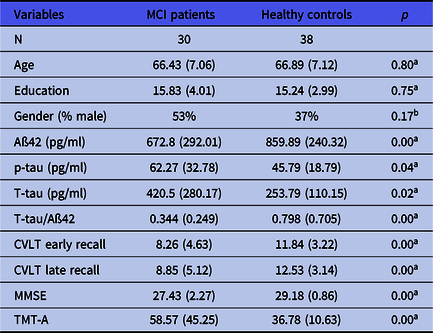

Group characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

Values denote mean raw scores (s.d.). MCI, mild cognitive impairment; p-tau, phospho-tau; T-tau, total tau. CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; TMT-A, Trail Making Test A.

a Mann–Whitney U-test.

b Chi-squared test.

Analysis of neuropsychological and CSF biomarker data

Statistical analysis of behavioural and CSF data was carried out using SPSS 25 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). A Kolgomorov–Smirnov test was used on all cognitive variables to test for the assumption of normality. To test for group differences (MCI vs. healthy controls) in normally distributed variables, a two-sample t-test was used. Group differences in variables that did not meet the assumption of normality were tested with a non-parametric test, the Mann–Whitney U-test. For all neuropsychological test scores that were significantly different between MCI patients and healthy controls, we examined the relationship between these scores and Aß42, T-tau and p-tau concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid. Associations between CSF biomarkers and cognition were investigated with Spearman’s partial correlation as variables were not normally distributed. In the first step, a Spearman partial correlation between neuropsychological test scores and CSF biomarker concentrations, adjusted for age and years of education, was calculated for a pooled total group consisting of both MCI patients and healthy controls. In the second step, the partial correlation coefficients were computed for each group separately. Initially, we had aimed to analyse the association between CSF biomarkers and intrinsic functional connectivity in the DMN. Since there were no significant differences in posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) resting connectivity between MCI patients and healthy controls, this analysis was not performed.

MRI hardware and procedure

All MR images were acquired using a Trio 3-T scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a standard head coil for radiofrequency transmission and signal reception. Participants were outfitted with protective earplugs to reduce scanner noise. For T1-weighted structural brain imaging, an optimised 3D modified driven equilibrium Fourier transform sequence (Deichmann et al., Reference Deichmann, Schwarzbauer and Turner2004) with the following parameters was conducted: acquisition matrix = 256 x 256, repetition time (TR) = 7.92 ms, echo time (TE) = 2.48 ms, field of view (FOV) = 256 mm, 176 slices and 1.0-mm slice thickness. Functional resting state images were acquired using a blood oxygen level-dependent-sensitive echo-planar imaging sequence comprising the following parameters: 300 volumes, voxel size: 3 × 3 × 3 mm3, TR = 2000 ms, TE = 30 ms, 30 slices, slice thickness = 3 mm, distance factor = 20%, flip angle = 90°, and FOV = 192 mm. The resting state measurements were part of a larger fMRI study on episodic memory. After participants had to encode and recognise face–name pairs in the scanner, the resting state measurements were subsequently assessed. For the resting state measurements, all participants were instructed to keep their eyes open, to lie still, not to engage in any speech, to think of nothing special and to look at a white fixation cross presented in the centre of the visual field during the whole scan.

Selection of seed region

To analyse DMN connectivity, we used a seed region-based approach. Because we were specifically interested in DMN resting state activity and its relation to CSF biomarker concentrations, we investigated the intrinsic functional connectivity of a region anatomically co-localised with the major posterior hub of the DMN (PCC). The PCC is an anatomical/computational hub in the DMN and brain in general (Hagmann et al., Reference Hagmann, Cammoun, Gigandet, Meuli, Honey, Wedeen and Sporns2008; Greicius et al., Reference Greicius, Supekar, Menon and Dougherty2009). Additionally to being an important component of the DMN, the PCC seems to be especially vulnerable towards AD pathology. Studies using fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) have consistently shown diminished resting state glucose metabolism in the PCC of patients with early AD (Buckner et al., Reference Buckner, Snyder, Shannon, Larossa, Sachs, Fotenos, Sheline, Klunk, Mathis, Morris and Mintun2005), MCI (Ishii et al., Reference Ishii, Mori, Hirono and Mori2003) and also in cognitively intact (Reiman et al., Reference Reiman, Caselli, Yun, Chen, Bandy, Minoshima, Thibodeau and Osborne1996; Small et al., Reference Small, Ercoli, Silverman, Huang, Komo, Bookheimer, Lavretsky, Miller, Siddarth, Rasgon, Mazziotta, Saxena, Wu, Mega, Cummings, Saunders, Pericak-Vance, Roses, Barrio and Phelps2000; Reiman et al., Reference Reiman, Chen, Alexander, Caselli, Bandy, Osborne, Saunders and Hardy2004; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Ayutyanont, Langbaum, Fleisher, Reschke, Lee, Liu, Alexander, Bandy, Caselli and Reiman2012) elderly persons, possibly reflecting synaptic decline in this region. The vulnerability of the PCC towards AD pathology and the fact that it is a key component of the DMN made it an ideal candidate region for investigating associations between intrinsic functional connectivity and its relation to CSF biomarkers of AD.

Image processing

Image processing Brain Voyager QX 2.3 (Brain Innovation, Maastricht, the Netherlands) was used to analyse the fMRI data (Goebel et al., Reference Goebel, Esposito and Formisano2006). Anatomical data were pre-processed with intensity inhomogeneity correction and transformed into Talairach space. Pre-processing of functional data included 3D motion correction to overcome minor head movements during the scan, slice scan time correction, spatial smoothing with a 4-mm Gaussian kernel (full-width at half-maximum) to accommodate inter-subject anatomical variability, temporal high-pass filtering to remove low-frequency non-linear drifts of three or fewer cycles per time course (cut-off = 0.0075 Hz) and linear trend removal. Quality assurance measures of head motion showed no group differences. The complete set of functional data of each subject was co-registered to the anatomical scans, transformed into Talairach space and resampled to an iso-voxel size of 3 × 3 × 3 mm3. We computed a seed-correlation analysis with a seed region localised in the left PCC. The seed location that was used for the resting state analysis (Fig. 1(A); Talairach coordinates: x = −2, y = −56, z = 18, 134 anatomical voxels) was derived from an event-related fMRI analysis of the same participants: it showed the strongest task-related deactivation during retrieval of face–name pairs and has been reported in the literature as a major hub of the DMN (Hagmann et al., Reference Hagmann, Cammoun, Gigandet, Meuli, Honey, Wedeen and Sporns2008; Buckner et al., Reference Buckner, Sepulcre, Talukdar, Krienen, Liu, Hedden, Andrews-Hanna, Sperling and Johnson2009; Greicius et al., Reference Greicius, Supekar, Menon and Dougherty2009). The analysis of intrinsic functional connectivity with the PCC as seed region was done using MATLAB software (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) version 2016a and freely available toolboxes and custom-written routines (https://vincentvandeven.weebly.com/my-own-software.html). The computation of group differences of intrinsic PCC functional connectivity comprised a two-level random effects analysis (Fox et al., Reference Fox, Snyder, Vincent, Corbetta, Van Essen and Raichle2005; Oertel-Knochel et al., Reference Oertel-Knochel, Knochel, Matura, Prvulovic, Linden and Van De Ven2013). At the first level, we first regressed out fMRI nuisance signals from the functional time series, which included the z-normalised signal sampled from the lateral ventricles, white matter, six motion correction parameters (Birn et al., Reference Birn, Diamond, Smith and Bandettini2006) and the global brain signal. We then sampled and z-normalised the temporal profile from the PCC seed region and correlated (Pearson’s r) it with the nuisance-corrected time series (residuals) in a voxel-by-voxel manner. The correlation values were normalised using Fisher’s Z and were then entered into the second level of the random effects analysis using an analysis of covariance with group as between-subjects factor, and age, sex and education as subject-level covariates. We performed a one-sample t-test to obtain a multi-subject map of overlapping spatial distributions of PCC-related connectivity across all subjects (one-sided to include only positive effects), and the results were visualised using a false discovery rate (FDR) of q = 0.05 (Genovese et al., Reference Genovese, Lazar and Nichols2002). Nuisance-corrected between-group effects were also corrected for multiple comparisons using an FDR of 0.05. FDR corrects for the expected proportion of false positives among those tests for which the null hypothesis was rejected. It has been shown to reliably reject false positives, albeit being less conservative than family-wise error correction (Genovese et al., Reference Genovese, Lazar and Nichols2002).

Fig. 1. Functional connectivity maps of the entire cohort (n = 68) showing blood oxygen level-dependent fluctuations during rest correlated with the left posterior cingulate cortex seed region (depicted in violet) demonstrating the default mode network (p < 0.001).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the MCI group and healthy controls are shown in Table 1. The Mann–Whitney U-test revealed no significant group differences in age and years of education (p > 0.05). There were also no significant group differences with regard to gender distribution (chi-squared test, p > 0.05). With regard to different subtypes of MCI, the group showed the following distribution: 15 patients with amnestic MCI, multiple domain (performing 1.5 standard deviations below the norm in two different cognitive domains, one of them memory), 13 patients with amnestic MCI, single domain (performing 1.5 standard deviations below the norm only in the memory domain) and 2 patients with non-amnestic MCI (performing 1.5 standard deviations below the norm in at least one domain and no memory impairment). MCI patients showed significantly lower concentrations of CSF Aß42 (p < 0.001) and higher concentrations of p-tau (p = 0.04) as well as T-tau (p = 0.02) than controls. Furthermore, MCI patients showed a much higher T-tau/Aß42 ratio than healthy controls (p = 0.004). The MCI group performed significantly worse than healthy controls in all neuropsychological tests.

Relationship between cognitive performance and CSF biomarkers

There were significant associations between CSF biomarker concentrations and cognitive performance in the MCI group (Table 2). Lower levels of Aß42 concentrations were associated with worse performance in verbal episodic memory (CVLT early recall r s = 0.51, p = 0.013, CVLT late recall r s = 0.44, p = 0.37, Fig. 2) and global cognitive functioning [Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) r s = 0.54, p = 0.008]. Similarly, a higher T-tau/Aß42 ratio was also associated with worse performance in verbal episodic memory (CVLT early recall r s = −0.52, p = 0.011; CVLT late recall r s = −0.48, p = 0.022, Fig. 1) and global cognitive function (MMSE r s = −0.55, p = 0.006). Higher levels of T-tau were associated with lower MMSE scores (r s = −0.47, p = 0.026). We did not find a relationship between CSF biomarker levels and cognitive performance in healthy controls (see Table 2).

Table 2. Relationship between cognitive performance and CSF biomarkers

MCI, mild cognitive impairment; CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; TMT-A, Trail Making Test A; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; p-tau, phospho-tau; T-tau, total tau; r s, Spearman’s correlation coefficient.*: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01

Resting state correlation analysis

Seed-correlation analysis of resting state signal fluctuations for a pooled total group consisting of both MCI patients and healthy controls (one-sample t-test, n = 68) revealed regions of significant connectivity [q (FDR) < 0.05], with the PCC seed region comprising extended areas of bilateral PCC and precuneus, bilateral medial frontal gyrus, bilateral superior frontal gyrus, bilateral parahippocampal gyrus/hippocampus, bilateral nucleus mediodorsalis and bilateral medial temporal gyrus (Fig. 1). This pattern largely resembles cortical regions of the DMN in cognitively normal elderly individuals (Greicius et al., Reference Greicius, Srivastava, Reiss and Menon2004; Spreng et al., Reference Spreng, Mar and Kim2009). The nuisance-corrected between-group comparison showed no significant differences in intrinsic functional connectivity between the PCC seed region and other areas of the brain [q (FDR) > 0.05].

Fig. 2. Relationship between CSF biomarkers and cognitive performance. Model predicted scores adjusted for age and education. MCI, mild cognitive impairment. Early recall and Late recall were assessed with the California Verbal Learning Test.

Discussion

Extending the findings of previous studies on the relationship between altered AD specific biomarker profiles and cognitive performance, we found that decreased Aß42 levels and elevated T-tau levels are closely associated with cognitive decline. MCI patients did not differ from cognitively normal controls with regard to intrinsic functional connectivity.

Our finding that Aß42 concentrations are closely associated with cognitive decline is in line with previous studies on the relationship between CSF biomarkers and cognitive performance. Several studies also found worse performance in different measures of memory to be associated with Aß42 burden in MCI patients (Hedden et al., Reference Hedden, Mormino, Amariglio, Younger, Schultz, Becker, Buckner, Johnson, Sperling and Rentz2012; Lim et al., Reference Lim, Ellis, Harrington, Kamer, Pietrzak, Bush, Darby, Martins, Masters, Rowe, Savage, Szoeke, Villemagne, Ames and Maruff2013; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Lim, Abbott, Galluzzi, Marizzoni, Babiloni, Albani, Bartres-Faz, Didic, Farotti, Parnetti, Salvadori, Muller, Forloni, Girtler, Hensch, Jovicich, Leeuwis, Marra, Molinuevo, Nobili, Pariente, Payoux, Ranjeva, Rolandi, Rossini, Schonknecht, Soricelli, Tsolaki, Visser, Wiltfang, Richardson, Bordet, Blin, Frisoni and Pharmacog2017). Unlike previous studies (Malpas et al., Reference Malpas, Saling, Velakoulis, Desmond and O’brien2015; Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Lim, Abbott, Galluzzi, Marizzoni, Babiloni, Albani, Bartres-Faz, Didic, Farotti, Parnetti, Salvadori, Muller, Forloni, Girtler, Hensch, Jovicich, Leeuwis, Marra, Molinuevo, Nobili, Pariente, Payoux, Ranjeva, Rolandi, Rossini, Schonknecht, Soricelli, Tsolaki, Visser, Wiltfang, Richardson, Bordet, Blin, Frisoni and Pharmacog2017), we did not find a significant association between T-tau levels, nor p-tau levels and memory performance. This finding might indicate that MCI patients who were included in our study were just at the beginning of the disease trajectory. It is assumed that amyloid accumulation precedes neocortical T-tau accumulation and neurodegeneration (Andreasen & Blennow, Reference Andreasen and Blennow2005).

Thus, at the beginning of the AD trajectory, there might be stronger associations between amyloid levels and cognitive performance in comparison to other CSF biomarkers (T-tau and p-tau). Since accumulation of Aß42 in the brain already begins before any cognitive symptoms are present and is closely associated with accelerated cognitive decline, Aß42 has been suggested to be a sensitive CSF biomarker for prodromal AD (Doraiswamy et al., Reference Doraiswamy, Sperling, Coleman, Johnson, Reiman, Davis, Grundman, Sabbagh, Sadowsky, Fleisher, Carpenter, Clark, Joshi, Mintun, Skovronsky, Pontecorvo and Group2012; Rowe et al., Reference Rowe, Bourgeat, Ellis, Brown, Lim, Mulligan, Jones, Maruff, Woodward, Price, Robins, Tochon-Danguy, O’keefe, Pike, Yates, Szoeke, Salvado, Macaulay, O’meara, Head, Cobiac, Savage, Martins, Masters, Ames and Villemagne2013; Lim et al., Reference Lim, Kalinowski, Pietrzak, Laws, Burnham, Ames, Villemagne, Fowler, Rainey-Smith, Martins, Rowe, Masters and Maruff2018). We found the T-tau/Aß42 ratio to show the strongest associations with memory decline and global cognitive functioning. This is in line with a study by Nathan et al. (Reference Nathan, Lim, Abbott, Galluzzi, Marizzoni, Babiloni, Albani, Bartres-Faz, Didic, Farotti, Parnetti, Salvadori, Muller, Forloni, Girtler, Hensch, Jovicich, Leeuwis, Marra, Molinuevo, Nobili, Pariente, Payoux, Ranjeva, Rolandi, Rossini, Schonknecht, Soricelli, Tsolaki, Visser, Wiltfang, Richardson, Bordet, Blin, Frisoni and Pharmacog2017) that also found associations between CSF biomarkers and cognition to become stronger, affecting broader cognitive domains when levels of both CSF tau and Aß42 are considered together. Thus, the T-tau/Aß42 ratio might be an even more sensitive biomarker for prodromal AD than Aß42 alone. However, this hypothesis should be further investigated using a much larger prospectively followed sample before definite conclusions can be drawn.

Our finding that intrinsic functional connectivity was not significantly different between MCI patients and cognitively healthy controls contradicts a number of studies that either found hyperconnectivity (Jin et al., Reference Jin, Pelak and Cordes2012; Esposito et al., Reference Esposito, Mosca, Pieramico, Cieri, Cera and Sensi2013) or hypoconnectivity (Sorg et al., Reference Sorg, Riedl, Muhlau, Calhoun, Eichele, Laer, Drzezga, Forstl, Kurz, Zimmer and Wohlschlager2007; Cha et al., Reference Cha, Jo, Kim, Seo, Kim, Yoon, Park, Na and Lee2013; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Risacher, West, Mcdonald, Magee, Farlow, Gao, O’neill and Saykin2013) in the DMN of MCI subjects. However, consistent with our study, a number of studies have also shown no alterations in resting state functional connectivity in the DMN of MCI patients (Binnewijzend et al., Reference Binnewijzend, Schoonheim, Sanz-Arigita, Wink, Van Der Flier, Tolboom, Adriaanse, Damoiseaux, Scheltens, Van Berckel and Barkhof2012; Zamboni et al., Reference Zamboni, Wilcock, Douaud, Drazich, Mcculloch, Filippini, Tracey, Brooks, Smith, Jenkinson and Mackay2013; Adriaanse et al., Reference Adriaanse, Sanz-Arigita, Binnewijzend, Ossenkoppele, Tolboom, Van Assema, Wink, Boellaard, Yaqub, Windhorst, Van Der Flier, Scheltens, Lammertsma, Rombouts, Barkhof and Van Berckel2014).

The lack of significant differences in DMN connectivity between MCI patients and healthy controls might be due to the heterogeneity of the MCI group investigated in this study. MCI patients differed with regard to their CSF profiles. Thus, 50% (n = 15) of MCI patients in this study showed a CSF Aß42 profile that was in line with the assumption of prodromal AD (<560 pg/ml), whereas Aß42 CSF profiles of the other MCI patients were within normal range. There is some evidence that amyloid load in the brain rather than MCI diagnosis is associated with alterations in intrinsic connectivity within the DMN. For instance, Adriaanse et al. (Reference Adriaanse, Sanz-Arigita, Binnewijzend, Ossenkoppele, Tolboom, Van Assema, Wink, Boellaard, Yaqub, Windhorst, Van Der Flier, Scheltens, Lammertsma, Rombouts, Barkhof and Van Berckel2014) found that functional connectivity within the DMN was reduced in subjects with high cerebral amyloid load, independent of diagnosis (AD, MCI or healthy controls). Similarly, Yi et al. (Reference Yi, Choe, Byun, Sohn, Seo, Han, Park, Woo and Lee2015) found reduced DMN functional connectivity in MCI subjects with high amyloid load compared to cognitive healthy controls. Interestingly, this pattern was reversed in MCI subjects with low cerebral amyloid load. Thus, MCI subjects with very little or low Aß42 deposition in the brain (measured with Carbon-11-labelled PiB (11C-PiB) PET) showed increased functional connectivity within the DMN compared to cognitively healthy controls and MCI subjects with high Aß42 deposition in the brain.

The big variation in resting neuronal activation patterns within the DMN depending on amyloid load might explain the lack of significant findings regarding DMN connectivity in our study. Since the MCI subjects in our study showed no consistent pattern of amyloid load in the brain (only 50% showing a pathological reduction of Aß42 in CSF), there might have been hypoconnectivity as well as hyperconnectivity within the DMN of our MCI subjects, thus showing no consistent pattern when the group was analysed altogether. In order to investigate the hypothesis of reduced DMN connectivity in MCI subjects with high amyloid load, we performed an additional analysis of resting state fMRI data. Only MCI subjects showing pathological Aß42 levels were included into this analysis. Moreover, cognitively healthy controls showing pathological Aß42 levels (n = 3) were excluded from the analysis. In contradiction to previous studies (e.g. Adriaanse et al. Reference Adriaanse, Sanz-Arigita, Binnewijzend, Ossenkoppele, Tolboom, Van Assema, Wink, Boellaard, Yaqub, Windhorst, Van Der Flier, Scheltens, Lammertsma, Rombouts, Barkhof and Van Berckel2014; Yi et al., Reference Yi, Choe, Byun, Sohn, Seo, Han, Park, Woo and Lee2015), subjects with high amyloid load in the brain (low CSF Aß42 concentrations) did not significantly differ from subjects with low Aß42 concentrations with respect to DMN functional connectivity. The lack of significant results [q (FDR) > 0.05] might have been due to the reduction of statistical power by analysing only half of the MCI group (n = 15).

A possible limitation of this study is the lack of an adjustment for multiple comparisons. We decided against an adjustment for multiple comparisons since we had a priori hypotheses regarding the CSF biomarkers for AD and their relationship with cognitive outcomes reported here.

A clear limitation of this study is the lack of longitudinal data. Our results indicate that CSF biomarkers are more closely related to cognitive impairment than alterations in resting state activity. However, longitudinal data would be needed to make assumptions about the ability of CSF biomarkers to predict cognitive decline. In the end, information on the progression of the cognitive impairment would be needed to state with certainty that the aberrant CSF biomarker profiles of our patients were a sign of incipient AD.

Taken together, our findings indicate that a decline in CSF Aß42 and an elevation of T-tau are related to changes in cognitive performance in MCI and might be a more reliable indicator of neurodegenerative processes than intrinsic functional connectivity. This assumption is in line with a study by Bertens et al. (Reference Bertens, Knol, Scheltens and Visser2015) which showed that Aß42 levels are abnormal already in incipient stages of AD before any cognitive symptoms are present. Their study also included measures of hippocampal volume and glucose metabolism (FDG-PET) that did not show any abnormalities in incipient AD.

Conclusion

We suggest that CSF biomarker profiles constitute a more robust marker of neurodegenerative processes underlying cognitive decline than intrinsic functional connectivity. Alterations in resting state functional connectivity do not seem to be consistent in MCI patients and are not likely to be closely related to cognitive function.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Neurodegeneration & Alzheimer’s disease research grant of the LOEWE program ‘Neuronal Coordination Research Focus Frankfurt’ (NeFF), awarded to J.P and D.P. The authors certify that there is no actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.