Significant outcomes

Chronic administration of 1-methyl-tryptophan (1-MT) (added at 2 g/l to the drinking water) shows anxiolytic properties.

Chronic oral administration of the indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase inhibitor 1-MT (2 g/l) is successful in lowering kynurenine and the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio following administration of lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

Blockade of tryptophan 2,3 dioxygenase by 680C91 (15 mg/kg) did not prevent LPS-induced anxiety or cognitive dysfunctions, nor did it affect LPS-induced increases in kynurenine and the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio and should thus not be the first therapeutic target considered in paradigms involving LPS-induced neuroinflammation.

Limitations

The effect of pair versus group housing was not explicitly tested.

Timing of lipopolysaccharide administration in the fear conditioning paradigm targets memory consolidation of the tone–shock association and not memory formation or recall. It is possible the inhibitors used in this study would rescue other types of cognitive deficits.

Only one concentration of 1-methyl-tryptophan and 680C91 was tested, and conclusions on their efficacy should be interpreted only in relation to those particular doses.

Introduction

Sustained immune activation in humans has been linked to development of depression and cognitive dysfunction (Dantzer et al., Reference Dantzer, O’Connor, Lawson and Kelley2011). Disturbances in the kynurenine pathway (KP) of tryptophan metabolism have been implicated in the pathogenesis of post-operative cognitive dysfunction (Yi et al., Reference Yi, Yang and Duan2015) and in the cognitive impairments reported after serious bacterial infections such as tick-borne encephalitis (Holtze et al., Reference Holtze, Mickiené, Atlas, Lindquist and Schwieler2012) and in murine sepsis models (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Kan, Wang, Yang and Zhang2016). In particular, elevated brain levels of the kynurenine pathway metabolite kynurenic acid (KYNA) have been linked to cognitive dysfunctions (Stone and Darlington, Reference Stone and Darlington2013; Sellgren et al., Reference Sellgren, Kegel, Bergen, Ekman, Olsson, Larsson, Vawter, Backlund, Sullivan, Sklar, Smoller, Magnusson, Hultman, Walther-Jallow, Svensson, Lichtenstein, Schalling, Engberg, Erhardt and Landén2016; Erhardt et al., Reference Erhardt, Pocivavsek, Repici, Liu, Imbeault, Maddison, Thomas, Smalley, Larsson, Muchowski, Giorgini and Schwarcz2017a; Erhardt et al., Reference Erhardt, Schwieler, Imbeault and Engberg2017b). Indeed, diminished synthesis of KYNA in rodents and primates is associated with improved cognition (Chess et al., Reference Chess, Simoni, Alling and Bucci2007; Potter et al., Reference Potter, Elmer, Bergeron, Albuquerque, Guidetti, Wu and Schwarcz2010; Kozak et al., Reference Kozak, Campbell, Strick, Horner, Hoffmann, Kiss, Chapin, McGinnis, Abbott, Roberts, Fonseca, Guanowsky, Young, Seymour, Dounay, Hajos, Williams and Castner2014).

Administration of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in mice leads to peripheral immune activation, neuroinflammation, and development of depression- and anxiety-like symptoms, long after the acute-sickness behaviour has ended (Yirmiya, Reference Yirmiya1996; O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Lawson, André, Moreau, Lestage, Castanon, Kelley and Dantzer2009), and disruptions in contextual fear conditioning (Terrando et al., Reference Terrando, Rei Fidalgo, Vizcaychipi, Cibelli, Ma, Monaco, Feldmann and Maze2010), a paradigm used to assess learning and memory (Kim & Fanselow, Reference Kim and Fanselow1992). LPS causes increases in cytokines [interleukin (IL)-1β, tumour necrosis factor-α, interferon-γ, IL-6, etc] in both periphery and brain (Dantzer, Reference Dantzer2001; Lawson et al., Reference Lawson, Parrott, McCusker, Dantzer, Kelley and O’Connor2013a; Skelly et al., Reference Skelly, Hennessy, Dansereau and Cunningham2013), which, in turn, increases expression of indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase (IDO1) (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Lawson, André, Moreau, Lestage, Castanon, Kelley and Dantzer2009), the rate-limiting enzyme of the kynurenine pathway that converts l-tryptophan into N-formylkynurenine (Shimizu et al., Reference Shimizu, Nomiyama, Hirata and Hayaishi1978; Takikawa et al., Reference Takikawa, Kuroiwa, Yamazaki and Kido1988; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Charych, Lee and Möller2014). N-formylkynurenine is then turned into l-kynurenine by kynurenine formamidase and is further metabolised either into KYNA via kynurenine acetyltransferase enzymes, anthranilic acid via kynureninase, or is processed via kynurenine monooxygenase down a pathway leading to production of quinolinic acid (QUIN). In the brain, downstream processing of l-kynurenine is compartmentalised with KYNA production in astrocytes and QUIN production in microglia (Amori et al., Reference Amori, Guidetti, Pellicciari, Kajii and Schwarcz2009). These downstream metabolites are neuroactive. Thus, in low micromolar concentrations, the neuroprotective KYNA is an antagonist at the glycine site of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor and a non-competitive antagonist of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (Hilmas et al., Reference Hilmas, Pereira, Alkondon, Rassoulpour, Schwarcz and Albuquerque2001). In higher concentrations, it also blocks kainate and alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazoleproprionic acid receptors (Perkins & Stone, Reference Perkins and Stone1982). Conversely, QUIN, being an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) agonist (Stone & Perkins, Reference Stone and Perkins1981), is considered neurotoxic. Exogenous administration of low doses of l-kynurenine, presumably through induced production of QUIN, is known to cause depression-like behaviour in the forced swim test (FST), tail suspension test (TST) (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Lawson, André, Moreau, Lestage, Castanon, Kelley and Dantzer2009), and sucrose preference test (Agudelo et al., Reference Agudelo, Femenia, Orhan, Porsmyr-Palmertz, Goiny, Martinez-Redondo, Correia, Izadi, Bhat, Schuppe-Koistinen, Pettersson, Ferreira, Krook, Barres, Zierath, Erhardt, Lindskog and Ruas2014).

Chronic inhibition of IDO1 using 1-methyl-tryptophan (1-MT) eliminates the anxiety and depression observed following LPS-induced inflammation in mouse, partly through reduction of the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Lawson, André, Moreau, Lestage, Castanon, Kelley and Dantzer2009). However, IDO1 is not the only enzyme capable of converting tryptophan into kynurenine. Tryptophan 2,3 dioxygenase (TDO2) is predominantly expressed in liver and brain and can also produce kynurenine, especially under stress conditions and/or when activated by corticosterone (Gibney et al., Reference Gibney, Fagan, Waldron, O’Byrne, Connor and Karkin2014) or pro-inflammatory cytokines (Sellgren et al., Reference Sellgren, Kegel, Bergen, Ekman, Olsson, Larsson, Vawter, Backlund, Sullivan, Sklar, Smoller, Magnusson, Hultman, Walther-Jallow, Svensson, Lichtenstein, Schalling, Engberg, Erhardt and Landén2016). 680C91 is a selective TDO2 inhibitor shown to increase brain tryptophan, serotonin (5-HT), and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) after acute per os administration in the rat (Salter et al., Reference Salter, Hazelwood, Pogson, Iyer and Madge1995); however, there is a paucity of information concerning its effects in mice.

Aims of the study

Here, we first determine the acute effects of TDO2 inhibition by 680C91 on kynurenine pathway metabolites and monoamines in mice. We then test the effect of chronic TDO2 inhibition or chronic IDO1 inhibition with regard to cognitive deficits and anxiety following LPS-induced neuroinflammation.

Materials and methods

Animals

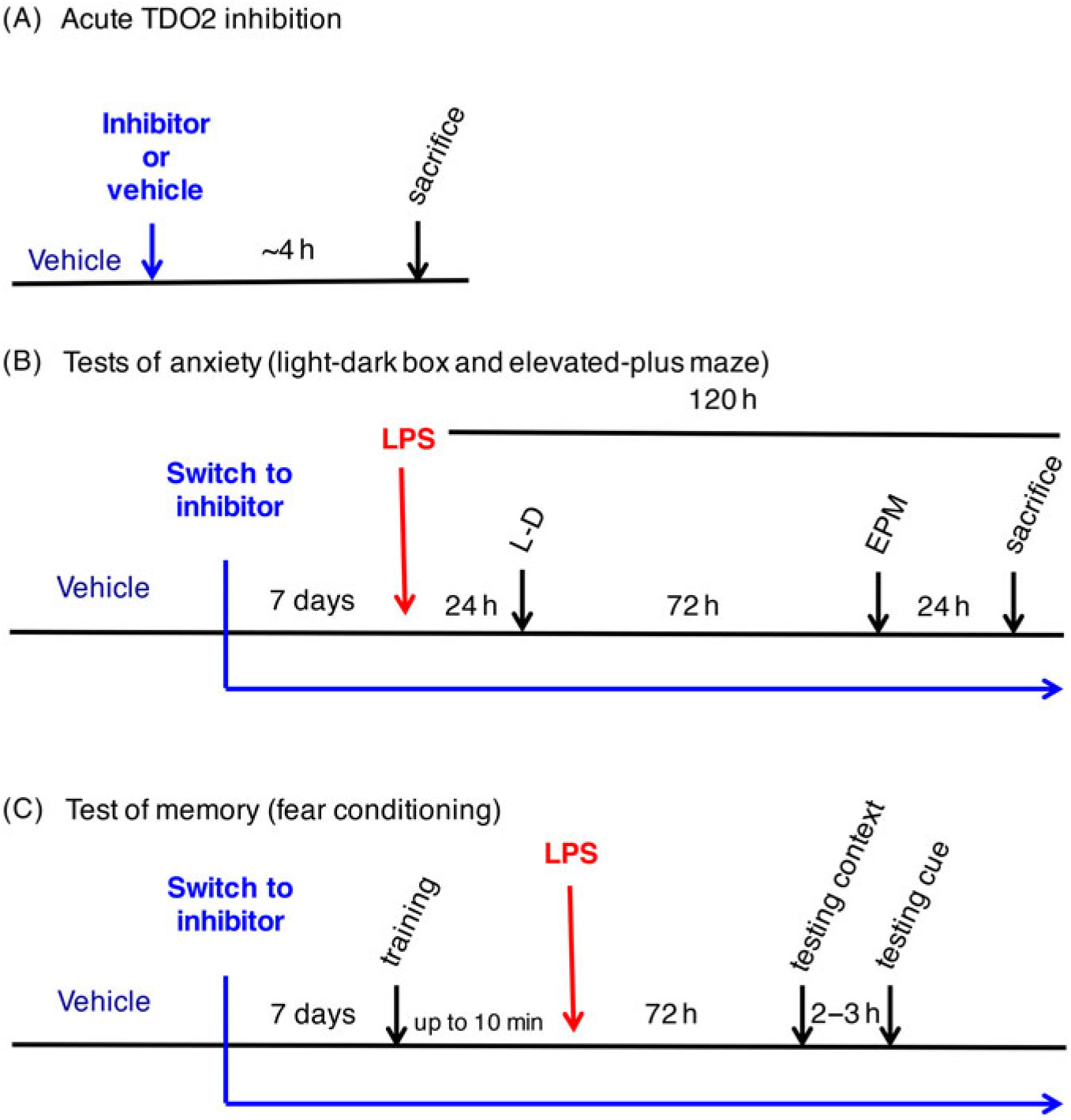

Male C57Bl6/NCrl mice aged 13–18 weeks were used in this study. Mice were group-housed (n = 2–6) on a 12-h light–dark cycle (lights on 06:00) with food and water provided ad libitum. To minimise possible fighting upon voluntary consumption of drug pellets, animals receiving 680C91 were housed in groups of 2. Experiments were carried out during the light phase (08:30–16:30). Experiments were approved by and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethical Committee of Northern Stockholm, Sweden. These guidelines do not allow for individual housing of animals and mandate a minimum of 3 days between behavioural tests, and thus animals first tested in the light–dark box were re-tested in the elevated plus maze 3 days later. There were four groups (vehicle/saline, vehicle/LPS, drug/saline, drug/LPS) each containing n = 6–8 mice, a number within the standards reported for this field (Miura et al., Reference Miura, Shirokawa, Isobe and Ozaki2009; Salazar et al., Reference Salazar, Gonzalez-Rivera, Redus, Parrott and O’Connor2012; Lawson et al., Reference Lawson, McCusker and Kelley2013b). All animals were habituated to being handled by an experimenter for at least 7 days prior to behavioural testing and were allowed to habituate to testing rooms for 30 min before the start of testing. Animals were tested according to the experimental designs depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Schematic representations of the experimental design. (A) Experiment 1 – Acute 680C91 administration. (B) Experiment 2 – light–dark box and elevated plus maze testing of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced anxiety-like behaviours. (C) Experiment 3 – Trace fear conditioning paradigm of LPS-induced cognitive deficits.

Tissue collection

Collection took place 24 h following behavioural testing or approximately 4 h following drug administration in the case of acute 680C91 administration. Animals were anaesthetised using isoflurane until loss of tail pinch reflex, decapitated, and trunk blood collected. Brains were dissected and rapidly frozen in isopentane on dry ice and stored at −80°C until further use.

High-performance liquid chromatography

KYNA, kynurenine, and tryptophan

Stored brain tissues were placed in threefold volume of (w/v) 0.4 M perchloric acid (PCA) + 0.1% sodium metabisulfite + 0,05% EDTA. For serum, a onefold volume of the above was used. Brains were then homogenised using a mechanical homogeniser (Ultra-Turrax; IKA, Stauffen, Germany). Brains and serum were spun at 21 000 × g for 5 min. Supernatants were transferred to a new tube, and 70% PCA was added at 10% volume (e.g., if supernatant is 400 µl, 40 µl 70% PCA is added). Samples were again centrifuged at 21 000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatants collected in a new tube for analysis. Aliquots of 20 µl were injected on an isocractic reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system. The mobile phase consisted of 50-mM sodium acetate + 7% acetonitrile (adjusted to pH 6.2 using acetic acid) and was pumped by an LC-10AD VP device (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min through a ReproSil-Pur C18 column (4 × 150 mm; Dr. Maisch GmbH, Ammerbuch, Germany). For detection of kynurenine and tryptophan, samples passed through a spectrometer (SPD-10A UV-VIS; Shimadzu Corporation) set to wavelengths of 360 and 240 nm, respectively (change performed at 5 min). A second mobile phase consisting of 0.5 M zinc acetate in water was then added at a flow rate of 10 ml/h with a Pharmacia P-500 unit (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden). KYNA was detected on a fluorescence detector (FP-2020 Plus; Jasco Ltd., Hachioji City, Japan) set to an excitation wavelength of 344 nm and an emission wavelength of 398 nm. Signals from the detectors were analysed using Datalys Azur (Grenoble, France). Retention times for KYNA, tryptophan, and kynurenine were 7, 7.3, and 4 min, respectively.

Dopamine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, homovanillic acid, 5-HT, and 5-HIAA

Aliquots (20 µl) of the supernatants collected above were neutralised and diluted by adding 160-µl dH2O and 20-µl NaOH. Samples were injected into a reverse-phase HPLC with a mobile phase consisting of 70-mM sodium acetate (pH 4.1, 20% methanol) +1.5-mM octanesulfonic acid + 0.01-mM disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid pumped through a C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm, ZORBAX Eclipse XDB-C18; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at a flow rate of 0.68 ml/min by an LC-20AD pump (Shimadzu Corporation). Samples were electrochemically quantified by sequential oxidation/reduction in a high-sensitivity analytical cell (ESA 5011; ESA Inc., Chelmsford, MA, USA) controlled by a potentiostat (Coulochem III; ESA Inc.) with applied potentials of 600 and −400 mV. Signals from the detector were analysed using Clarity chromatography software (DataApex, Prague, Czech Republic). Retention times were 4 min for 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), 6 min for dopamine (DA), 7 min for homovanillic acid (HVA), 5.5 min for 5-HIAA, and 11.5 min for 5-HT.

Drugs

1-MT (Aldrich cat no. 860646) was administered at 2 g/l in sweetened drinking water for 1 week prior to LPS injection and throughout the behavioural experiments. Animals in the vehicle-treated groups received only sweetened tap water. This administration method has previously been shown to be effective in distributing 1-MT into the blood and to have effects on the cardiovascular system and tumour progression (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Muller, Sharma, DuHadaway, Banerjee, Johnson, Mellor, Prendergast and Munn2007; Polyzos et al., Reference Polyzos, Ovchinnikova, Berg, Baumgartner, Agardh, Pirault, Gisterå, Assinger, Laguna-Fernandez, Bäck, Hansson and Ketelhuth2015). The racemic mixture of 1-MT has previously been used to alleviate LPS-induced anxiety- and depression-like symptoms (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Lawson, André, Moreau, Lestage, Castanon, Kelley and Dantzer2009; Salazar et al., Reference Salazar, Gonzalez-Rivera, Redus, Parrott and O’Connor2012) and shown to pass the blood-brain barrier (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Lawson, André, Moreau, Lestage, Castanon, Kelley and Dantzer2009).Vehicle- and 1-MT-treated groups consumed a similar amount of fluid (trace fear conditioning experiment: vehicle 3.7 ± 0.3 ml/day, 1-MT 3.9 ± 0.3 ml/day; light–dark box/elevated plus maze experiment: vehicle 3.9 ± 0.3 ml/day, 1-MT 3.6 ± 0.4 ml/day). The TDO2 inhibitor 680C91 was purchased from Tocris Biosciences (cat. no. 4392) and administered at 15 mg/kg per os in 1 : 1 sweet condensed milk (SCM) in water (Tørsleffs, Thalfang, Germany). Dose was modified from that used in Salter et al. (Reference Salter, Hazelwood, Pogson, Iyer and Madge1995) (7.5 mg/kg per os in rat, the maximally effective dose shown to increase brain Trp, 5-HT, and 5-HIAA) according to equivalent body surface area conversion from rat to mouse. As TDO2 is a stress reactive enzyme, gavage stress wanted to be avoided. Therefore, drug or vehicle (1 : 1 SCM in water) was pre-measured and administered as ‘pellets’ in the cap of 1.5-ml microfuge tubes and placed in the cage where animals fed themselves. Animals received one pellet of vehicle or drug per day for 1 week prior to LPS injection and throughout the behavioural experiments for chronic TDO2 inhibition. For acute treatment, animals recived a pellet ~4 h prior to sacrifice. Each animal received a ‘pellet’ to minimise fighting. Animals were initially observed to ensure that they consumed all the contents.

LPS administration

Freshly prepared LPS (from E. Coli; Sigma L-2630, serotype O111:B4) was administered intraperitoneally at a dose of 0.83 mg/kg in physiological saline. This dose of LPS has been used extensively in similar experiments by us (Larsson et al., Reference Larsson, Faka, Bhat, Imbeault, Goiny, Orhan, Oliveros, Ståhl, Liu, Choi, Sandberg, Engberg, Schwieler and Erhardt2016) and others (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Lawson, André, Moreau, Lestage, Castanon, Kelley and Dantzer2009; Painsipp et al., Reference Painsipp, Köfer, Sinner and Holzer2011; Salazar et al., Reference Salazar, Gonzalez-Rivera, Redus, Parrott and O’Connor2012) and been shown to increase brain IDO activity (Lestage et al., Reference Lestage, Verrier, Palin and Dantzer2002). Lot #011M4008V was used throughout except for a subset of 680C91-treated animals in the light–dark/elevated plus maze experiment where lot#091M4031V was used because the previous lot ran out. Body weight was measured at 6-, 24-, 48-, and 72-h post-injection to monitor the effect of LPS. A humane end point was defined as a loss of more than 15% of the body weight but this was never encountered.

Trace fear conditioning

Trace fear conditioning (TFC) was carried out as in Terrando et al. (Reference Terrando, Rei Fidalgo, Vizcaychipi, Cibelli, Ma, Monaco, Feldmann and Maze2010) and Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Holtze, Powell, Terrando, Larsson, Persson, Olsson, Orhan, Kegel, Asp, Goiny, Schwieler, Engberg, Karlsson and Erhardt2014) using the fear conditioning chamber from MedAssociates and VideoFreeze software (version 2.5.5.0; MedAssociates Inc., Fairfax, VT, USA). Three rooms were used for holding the animals before, during, and after the test. Animals were individually brought from the first holding room to the testing room in a carrying cage (containing soiled bedding from their homecages) and placed in the conditioning chamber. Upon completion of the session, animals were placed in a new holding cage (also containing soiled homecage bedding, food pellets, cardboard hut, and water bottle) in a different room. All animals within one cage were tested with individuals tested at random during each session (training, cue, and context). The cage order for testing was also randomised. The training session lasted 310 s and consisted of two tone–shock pairings. The tones were 20 s in length (90 dB) and placed at 100 and 240 s within the session. The foot shock (2 s, 0.5 mA) was initiated 18 s following the end of the tone and finished 20 s following the tone. LPS was given within 10 min of the end of the training session. Contextual and cued fear conditioning were examined 72 h later, in that order, to ensure that sickness behaviour did not interfere with the assessment. The context session consisted of the animals being placed in the chamber for a similar amount of time as the training without presentation of tone or foot shock. The cued session consisted of the same timing for tone presentation as in the training session with no foot shock. The conditioning chamber had also been modified by placing two inserts (a white floor over the grid bars and a black pyramidal ‘roof’) in order to provide a different context. In training and cued sessions, the first 60 s were considered habituation time.

Light–dark box

The light–dark box test was performed 24 h following LPS administration similar to that in Erhardt et al. (Reference Erhardt, Pocivavsek, Repici, Liu, Imbeault, Maddison, Thomas, Smalley, Larsson, Muchowski, Giorgini and Schwarcz2017a). The box is made of Plexiglass (50 × 25 × 25 cm) and is equally divided into two compartments (one black and one white) separated by a partition with a 10 × 5 cm opening in the centre. Each mouse was placed in the centre of the wall facing away from the partition in the light section and allowed to explore the box freely for 10 min while being recorded with an overhead digital video camera. Urine and faeces were removed and the box cleaned with 70% EtOH between subjects. Illumination in the centre of the light side was 460–500 lx, while the dark compartment was covered with a lid. Since animals are initially placed in the light compartment, the voluntary time spent in the light is used. Videos were recorded for 10 min and analysed using Noldus EthoVision XT software (version 11.5; Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, the Netherlands).

Elevated plus maze

The elevated plus maze was performed 96 h following LPS administration in concordance with methods in Erhardt et al. (Reference Erhardt, Pocivavsek, Repici, Liu, Imbeault, Maddison, Thomas, Smalley, Larsson, Muchowski, Giorgini and Schwarcz2017a). The maze consists of two open (30 × 5 cm) and two enclosed (30 × 5 × 15 cm) runways in a ‘plus’ shape and is elevated 50 cm above the ground. Illumination on the open arms was 260–290 lx and <5 lx in the closed arms. Animals were started in the centre of the maze facing towards an open arm. The maze was cleaned with 70% EtOH between subjects. Animals were recorded via a ceiling-mounted video camera for 5 min. Videos were recorded and analysed using Noldus EthoVision XT software (Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, the Netherlands).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Mann–Whitney U-test was used when comparing two groups of data. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post hoc Sidak or Tukey, as indicated, was used to assess the impact of LPS administration (saline or LPS) and drug (vehicle or 1-MT or 680C91) on behaviour and kynurenine pathway metabolites. When appropriate, such as in measurements of the same animal, repeated measures two-way ANOVA was used. Results with p < 0.05 were considered significant.

Result

Acute TDO2 inhibition elevates tryptophan in brain

We investigated the acute effects of a dose of 15 mg/kg of 680C91 on the kynurenine pathway of tryptophan metabolism and levels of monoamines (Table 1). Animals were habituated to consume the vehicle for 2 days prior to drug administration to combat neophobia. On the test day, animals were given either vehicle or 680C91 and sacrificed, on average, 250 min following consumption (vehicle 248 ± 5 min, 680C91 250 ± 4 min). Inhibition of TDO2 caused a significant increase in brain tryptophan (p = 0.018, Mann–Whitney) but not in kynurenine (p = 0.081), KYNA (p = 0.83), kynurenine:tryptophan (p = 0.89), 5-HT (p = 0.96), 5-HIAA (p = 0.68), 5-HIAA:5-HT (p = 0.96), DA (p = 0.21), HVA (p = 0.54), DOPAC (p = 0.68), HVA:DA (p = 0.46), and DOPAC:DA (p = 0.96) at this timepoint following 680C91 administration.

Table 1. Kynurenine pathway metabolite and monoamine levels in brain following acute administration of 680C91

5-HIAA, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; 5-HT, serotonin; DA, dopamine; DOPAC, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid; HVA, homovanillic acid; KYNA, kynurenic acid.

* p < 0.05, a p = 0.08.

Different effects of chronic IDO1 and TDO2 inhibition on LPS-induced anxiety

We used the light–dark box and elevated plus maze tests to investigate levels of anxiety. The tests were performed 24 and 96 h following LPS administration, respectively, to avoid possible crosstalk between the tests [Fig. 1(B)]. LPS caused a significant reduction in the time spent in the light compartment of the light–dark box in both 1-MT experiments [Fig. 2(A), ## p = 0.002] and those with 680C91 [Fig 2(B), # p = 0.047]. LPS also reduced the number of light entries in these experiments [Fig. 2(C), # p = 0.012; Fig. 2(D), # p = 0.010]. Together, these parameters indicate increased anxiety-like behaviours 24 h following LPS administration. Neither chronic blockade of IDO1 nor chronic blockade of TDO2 was able to rescue the increased anxiety produced by LPS in these animals (LPS × 1-MT interaction: time in light p = 0.40; number of light entries p = 0.92; LPS × 680C91 interaction: time in light p = 0.15; number of light entries p = 0.76). Likewise, there were no significant effects of the drugs on anxiety parameters (1-MT: time in light p = 0.46; number of light entries p = 0.32; 680C91: time in light p = 0.69; number of light entries p = 0.76). Three days following the light–dark box, animals were tested in the elevated plus maze [Fig. 2(E) and (F)]. In the 1-MT experiments, LPS had lost its anxiogenic effect by this time [Fig. 2(E), p = 0.47]. In the experiments with 680C91, LPS caused a significant decrease in the time spent in the open arms [Fig. 2(F), # p = 0.024]; however, the anxiogenic effects of LPS were not abrogated by this chronic treatment with the TDO2 inhibitor (p = 0.48) nor did 680C91 have effects of its own in this paradigm (p = 0.78). There were no significant LPS × drug interactions in the 1-MT experiment (p = 0.16). However, 1-MT showed general anxiolytic properties by significantly increasing the time spent in the open arms [Fig. 2(E), # p = 0.013] with especially significant differences between vehicle- and 1-MT-treated animals that never received LPS (*p = 0.016, post hoc Sidak).

Fig. 2. Inhibition of indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase or tryptophan 2, 3 dioxygenase differentially modulates anxiety parameters. (A) Amount of time (s) spent in the light compartment of the light–dark box test 24 h following lipopolysaccharide (LPS) administration in 1-methyl-tryptophan (1-MT)-treated mice (two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), **p < 0.01 post hoc Sidak vs. saline-treated condition). (B) Amount of time (s) spent in the light compartment of the light–dark box test 24 h following LPS administration in 680C91-treated mice (two-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 post hoc Sidak vs saline). (C) Number of entries into the light compartment in the light–dark box test in 1-MT-treated animals. (D) Number of entries into the light compartment in the light–dark box test for 680C91-treated animals. (E) Time spent in the open arms of the elevated plus maze for 1-MT-treated animals (two-way ANOVA, *p < 0.05 post hoc Sidak vs. vehicle-treated animals). (F) Time spent in the open arms of the elevated plus maze for 680C91-treated mice. # p < 0.05 and ## p < 0.01 represent main effects of drug or LPS, as indicated. n = 6 vehicle/saline, n = 6 vehicle/LPS, n = 7 1-MT/saline, n = 8 1-MT/LPS; n = 7 across all groups in 680C91 experiments.

Effects of chronic IDO1 and TDO2 inhibition on LPS-induced cognitive deficits

Cued- and contextual fear conditioning were examined as depicted in Fig. 1(C). It should be noted that LPS was administered within 10 min of the training phase of the trace fear conditioning paradigm, while memory recall of the tone and context pairing with the foot shock was examined 72 h later as in Terrando et al. (Reference Terrando, Rei Fidalgo, Vizcaychipi, Cibelli, Ma, Monaco, Feldmann and Maze2010). Chronic drug treatment with 1-MT or 680C91 did not affect the pairing of the tone and context with the foot shock [Supplementary Fig. S1(A) and (B)]. During the recall phase, no effect was seen on conditioning in response to the cue in either condition [Fig. 3(A) and (B), 1-MT: effect of LPS p = 0.52, effect of drug p = 0.15, LPS × drug interaction p = 0.40; 680C91: effect of LPS p = 0.11, effect of drug p = 0.26, LPS × drug interaction p = 0.67]. Regarding conditioning to context, LPS caused a significant reduction in freezing in both experiments [Fig. 3(C), ### p = 0.0003; Fig. 3(D), # p = 0.011]. This effect was not abrogated by this concentration of 1-MT [Fig. 3(C), LPS × drug interaction p = 0.94] or this dose of 680C91 [Fig. 3(D), LPS × drug interaction p = 0.94]. In fact, chronic administration of 1-MT decreased freezing overall [Fig. 3(C), # p = 0.019], while chronic administration of 680C91 increased freezing [Fig. 3(D), # p = 0.015] suggestive of effects of these drugs on anxiety-like behaviours.

Fig. 3. Neither indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase or tryptophan 2, 3 dioxygenase inhibition rescue lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced cognitive deficits in trace fear conditioning. (A) Amount of freezing (%) induced by the cue in 1-methyl-tryptophan (1-MT)-treated cohorts. (B) Amount of freezing (%) induced by the cue in 680C91-treated cohorts. (C) Amount of freezing (%) observed in the context phase of the trace fear conditioning paradigm in 1-MT-treated cohorts [two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, post hoc Sidak]. (D) Amount fo freezing (%) observed in the context test phase of the TFC paradigm in 680C91-treated animals. # p < 0.05, represents main effects of drug or LPS, as indicated. (E) Changes in body weight in 1-MT-treated cohorts following LPS injection (two-way ANOVA with repeated measures, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 post hoc Tukey vs. saline-treated controls, #p < 0.05 post hoc Tukey vs. the vehicle + LPS-treated group). (F) Changes in body weight in 680C91-treated cohorts following LPS injection (two-way ANOVA with repeated measures, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ***p < 0.001 post hoc Tukey vs. saline-treated controls). n = 6 vehicle/saline, n = 7 vehicle/LPS, n = 8 1-MT/saline, n = 8 1-MT/LPS, n = 8 across all groups in 680C91 experiments.

Effects of chronic IDO1 and TDO2 inhibition on LPS-induced body weight changes

Body weight following LPS injection was monitored throughout the behavioural testing. LPS caused a significant change in body weight compared to saline-injected controls peaking at 24 h following injection. At this time, the average change in body weight in the 1-MT experiment was 0.2 ± 0.2 g in vehicle/saline, −0.5 ± 0.2 g in 1-MT/saline, −2.3 ± 0.2 g in vehicle/LPS, and −3.2 ± 0.4 g in 1-MT/LPS-treated animals [Fig. 3(E), effect of LPS p < 0.001, effect of time p = 0.0002, LPS × time interaction p < 0.001]. In animals treated chronically with the TDO2 inhibitor 680C91, the average was similar: −0.4 ± 0.3 g vehicle/saline, −0.4 ± 0.3 g 680C91/saline, −2.9 ± 0.2 g vehicle/LPS, and −2.6 ± 0.2 g 680C91/LPS [Fig. 3(F), effect of LPS p < 0.001, effect of time p < 0.001, LPS × time interaction p < 0.001]. However, 1-MT seemed to exacerbate weight-loss compared to vehicle-treated mice, which was most pronounced 48 h following LPS injection [Fig. 3(E), 0.0 ± 0.3 g in vehicle/saline, −0.6 ± 0.3 g in 1-MT/saline, −1.6 ± 0.3 g in vehicle/LPS, and −2.6 ± 0.3 g in 1-MT/LPS, #p < 0.05 post hoc Tukey], whereas TDO2 inhibition did not aggravate weight-loss compared to vehicle-treated counterparts [Fig. 3(F), 0.1 ± 0.3 g vehicle/saline, 0.0 ± 0.2 g 680C91/saline, −2.9 ± 0.4 g vehicle/LPS, and −2.5 ± 0.3 g 680C91/LPS].

Kynurenine pathway metabolites following chronic blockade of IDO1 or TDO2

Brains were collected 120 h after LPS administration and 24 h following performance in the elevated plus maze [Fig. 1(B)]. At this time point, there were no significant effects of LPS on brain levels of tryptophan (Table 2; p = 0.80), kynurenine (p = 0.36), KYNA (p = 0.72), kynurenine:tryptophan (p = 0.20), 5-HT (p = 0.40), 5-HIAA (p = 0.76), 5-HIAA:5-HT (p = 0.19), DA (p = 0.73), HVA (p = 0.14), DOPAC (p = 0.85), HVA:DA (p = 0.13), or DOPAC:DA (p = 0.48) in the 1-MT cohorts. However, in serum, there was a significant effect of LPS on the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio (p = 0.017). Serum tryptophan (p = 0.84), kynurenine (p = 0.062), and KYNA (p = 0.70) were not significantly changed at this time. No significant LPS × drug interactions were detected in this set of experiments for tryptophan (p = 0.47), kynurenine (p = 0.41), KYNA (p = 0.069), kynurenine:tryptophan (p = 0.44), 5-HT (p = 0.90), 5-HIAA (p = 0.67), 5-HIAA:5-HT (p = 0.70), DA (p = 0.25), HVA (p = 0.14), DOPAC (p = 0.48), HVA:DA (p = 0.080), and DOPAC:DA (p = 0.25) from brain or in serum tryptophan (p = 0.72), kynurenine (p = 0.59), KYNA (p = 0.24), or kynurenine:tryptophan (p = 0.94). However, chronic administration of 1-MT significantly decreased the level of brain kynurenine in both saline- and LPS-injected animals (p = 0.011) compared to those receiving vehicle (sweetened tap water). The effect is especially pronounced between vehicle/saline and 1-MT/saline groups (p = 0.040, post hoc Sidak). Chronic inhibition by 1-MT also significantly decreased the brain kynurenine:tryptophan ratio in both saline- and LPS-injected mice (p = 0.012) with a significant decrease in the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio between 1-MT/LPS-injected mice compared to vehicle/LPS-injected mice (p = 0.042, post hoc Sidak). There were no significant effects of 1-MT on brain tryptophan (p = 0.77), KYNA (p = 0.29), 5-HT (p = 0.35), 5-HIAA (p = 0.93), 5-HIAA:5-HT (p = 0.24), DA (p = 0.99), HVA (p = 0.12), DOPAC (p = 0.47), HVA:DA (p = 0.12), and DOPAC:DA (p = 0.29). Chronic 1-MT administration had no effect on serum tryptophan (p = 0.64), kynurenine (p = 0.87), KYNA (p = 0.49), or kynurenine:tryptophan (p = 0.22). In the experiments using 680C91, LPS significantly increased brain levels of kynurenine (Table 3; p = 0.008, 680C91/sal vs. 680C91/LPS p = 0.014 post hoc Sidak) and the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio (p = 0.006, 680C91/sal vs. 680C91/LPS p = 0.012 post hoc Sidak) but not that of tryptophan (p = 0.21), KYNA (p = 0.085), 5-HT (p = 0.63), 5-HIAA (p = 0.82), 5-HIAA:5-HT (p = 0.88), DA (p = 0.86), HVA (p = 0.58), DOPAC (p = 0.79), HVA:DA (p = 0.47), or DOPAC:DA (p = 0.57). In serum, significant LPS-induced increases in kynurenine (p < 0.001), KYNA (p = 0.020), and the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio (p < 0.001) were detected. Serum tryptophan remained unaffected (p = 0.24). No significant LPS × drug interactions were detected for tryptophan (p = 0.12), kynurenine (p = 0.21), KYNA (p = 0.30), kynurenine:tryptophan (p = 0.22), 5-HT (p = 0.12), 5-HIAA (p = 0.10), 5-HIAA:5-HT (p = 0.55), DA (p = 0.28), HVA (p = 0.056), DOPAC (p = 0.059), HVA:DA (p = 0.79), and DOPAC:DA (p = 0.64) in brain. There were also no significant LPS × drug interactions in serum levels of tryptophan (p = 0.50), kynurenine (p = 0.20), KYNA (p = 0.33), and kynurenine:tryptophan (p = 0.14). Chronic administration of 680C91 significantly increased brain levels of tryptophan (p = 0.012, Veh/sal vs. 680C91/sal p = 0.011, post hoc Sidak) and 5-HIAA (p = 0.023, veh/LPS vs. 680C91/LPS p = 0.015, post hoc Sidak) but not those of kynurenine (p = 0.14), KYNA (p = 0.25), kynurenine:tryptophan (p = 0.58), 5-HT (p = 0.31), 5-HIAA:5-HT (p = 0.10), DA (p = 0.46), HVA (p = 0.63), DOPAC (p = 0.27), HVA:DA (p = 0.32), or DOPAC:DA (p = 0.63) nor of serum tryptophan (p = 0.14), kynurenine (p = 0.62), KYNA (p = 0.098), or kynurenine:tryptophan (p = 0.22).

Table 2. Kynurenine pathway metabolite and monoamine levels following LPS-induced inflammation and chronic indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase inhibition

1-MT, 1-methyl-tryptophan; 5-HIAA, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; 5-HT, serotonin; DA, dopamine; DOPAC, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid; HVA, homovanillic acid; KYNA, kynurenic acid; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

a Significant effect of drug (1-MT), b Significant effect of LPS, two-way ANOVA; *p < 0.05 versus respective control condition (vehicle for 1-MT, saline for LPS) post hoc Sidak.

Table 3. Kynurenine pathway metabolite and monoamine levels following LPS-induced inflammation and chronic tryptophan 2, 3 dioxygenase inhibition

5-HIAA, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; 5-HT, serotonin; DA, dopamine; DOPAC, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid; HVA, homovanillic acid; KYNA, kynurenic acid; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

a Significant effect of drug (680C91), b Significant effect of LPS, two-way ANOVA; *p < 0.05 versus respective vehicle condition, # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 versus respective saline condition post hoc Sidak.

Discussion

The results of the present study show that, in line with existing literature, administration of LPS induces cognitive deficits and anxiety in mice and that this effect was accompanied by an increased brain and serum kynurenine:tryptophan ratio. Chronic administration of the IDO1 inhibitor, 1-MT, or of the TDO2 inhibitor 680C91 could not rescue these behaviours at these doses. Chronic administration of 680C91 was found to have slight anxiogenic properties by itself, while chronic administration of 1-MT on its own shows anxiolytic properties. Chronic 1-MT reduced both the basal and LPS-induced levels of kynurenine and the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio in brain. Conversely, chronic treatment with 680C91 had no effect on LPS-induced increases in brain and serum kynurenine, kynurenine:tryptophan ratio, and in serum only, KYNA levels. However, acute or chronic inhibition by 680C91 of its own, at this dose, increased brain levels of tryptophan and modified serotonergic metabolism.

Our experiments show that chronic administration of 1-MT (2 g/l) or chronic administration of 680C91 (15 mg/kg/day) is not effective in mitigating the cognitive deficits in contextual fear conditioning induced by LPS. There are three stages of memory involved in fear conditioning: initial formation of the tone/context–shock association, memory consolidation, and memory retrieval. When injected following training (initial memory formation of the tone/context–shock association) as we have done here, LPS disrupts memory consolidation of this association (Pugh et al., Reference Pugh, Kumagawa, Fleshner, Watkins, Maier and Rudy1998). Our results suggest that activation of IDO1 and TDO2, and the increased activity of the kynurenine pathway following LPS, either does not play a role in memory consolidation and that deficits observed in contextual fear memory are due to another factor or that the increase in KP metabolites that might interfere with learning and memory processes occurs after consolidation has already taken place. For example, it is known that brain KYNA levels are tightly linked to cognitive performance, and as an NMDAR antagonist, KYNA can disrupt learning and memory processes but previous data from our laboratory has shown that KYNA begins to rise in brain after 8 h following LPS administration (Larsson et al., Reference Larsson, Faka, Bhat, Imbeault, Goiny, Orhan, Oliveros, Ståhl, Liu, Choi, Sandberg, Engberg, Schwieler and Erhardt2016), past the window for conslidation processes. Furthermore, LPS-induced neuroinflammation elevates levels of multiple cytokines, many of which have signalling functions in healthy brain (Priteo & Cotman, Reference Priteo and Cotman2017). Of particular interest is IL-1β, which, at elevated levels, disrupts contextual fear conditioning (Pugh et al., Reference Pugh, Kumagawa, Fleshner, Watkins, Maier and Rudy1998; Terrando et al., Reference Terrando, Rei Fidalgo, Vizcaychipi, Cibelli, Ma, Monaco, Feldmann and Maze2010). It is possible that IL-1β or another cytokine is having effects independent of the kynurenine pathway and for which inhibiton of IDO1 and TDO2 would not be effective.

Chronic inhibition of IDO1 by this dose of 1-MT surprinsingly did not abrogate the anxiety-like behaviour seen in the light–dark box following LPS-induced neuroinflammation even though 1-MT still significantly reduced the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio in LPS-injected animals compared to vehicle-LPS controls at tissue collection. Behavioural differences in measures of anxiety between our study and others (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Lawson, André, Moreau, Lestage, Castanon, Kelley and Dantzer2009; Salazar et al., Reference Salazar, Gonzalez-Rivera, Redus, Parrott and O’Connor2012) may be related to differences in mouse strain, light-phase testing, serotype of LPS, route of administration (subcutaneous following surgical implant of a pellet or repeated subcutaneous injections vs. per os voluntary consumption), or social status of animals. Indeed, we used group-housed animals, while the majority of previous studies have examined individually housed mice. Isolation stress has been shown to alter several aspects of mouse behaviour, and it is sometimes used to model aspects of schizophrenia, a serious neuropsychiatric disorder. Tryptophan metabolism along the kynurenine pathway and levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are also influenced by isolation stress in mice (Miura et al., Reference Miura, Shirokawa, Isobe and Ozaki2009; Möller et al., Reference Möller, Du Preez, Viljoen, Berk, Emsley and Harvey2013). Consistent with LPS-induced depressive-like behaviours reported by many laboratories, work by Painsipp et al. (Reference Painsipp, Köfer, Sinner and Holzer2011) demonstrates that individually housed C57Bl/6 mice administered 0.83-mg/kg LPS show increased immobility time in the FST compared to saline-treated controls 24 h following LPS injection. However, group-housed animals tested in the same paradigm show a reduction in immobility even though the measured biochemical parameters (plasma corticosterone and IL-6) were similar in both groups following LPS (Painsipp et al., Reference Painsipp, Köfer, Sinner and Holzer2011). This indicates social housing can significantly change depression-related behaviours following LPS-induced neuroinflammation without concomitant differences in biochemical parameters. Furthermore, it has been shown that low social support is also a risk factor in human cytokine-induced depression (Capuron et al., Reference Capuron, Ravaud, Miller and Dantzer2004). It is therefore possible that the social housing in our experiments imparts a resistance to the effects of IDO1, and possibly TDO2, inhibition on the behavioural readouts of anxiety and cognitive deficits elicited by LPS despite, at least for the 1-MT experiments, a reduction in levels of brain kynurenine and the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio, a biochemical parameter also changed in other experiments (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Lawson, André, Moreau, Lestage, Castanon, Kelley and Dantzer2009). Furthermore, in the 680C91 experiment, where the animals were paired-housed, we saw prolonged effects of LPS on anxiety [96-h post-LPS administration, as seen in Fig. 2(F)] and biochemical parameters (brain kynurenine and kynurenine:tryptophan ratio, serum kynurenine, KYNA, and kynurenine tryptophan ratio, data presented in Table 3) in both 680C91/LPS-treated and vehicle/LPS-treated mice, while no such effects were observed in the group-housed vehicle/LPS-treated mice from the 1-MT experiments [data presented in Table 2 and Fig. 2(E)]. While this is an anecdotal observation from our study, the direct effects of single versus group housing require further testing. Interestingly, chronic inhibition of IDO1 in 1-MT/saline-treated animals resulted in levels of kynurenine that were half of those in vehicle/saline-treated animals in brain but the serum levels of kynurenine were unaffected. This suggests that regulation of IDO1 activity may be different in periphery and brain. We find here that kynurenine levels are significantly elevated in animals displaying anxiety in the elevated plus maze and that they are decreased in animals showing anxiolytic behaviour in this test. These data are in accordance with reports that administration of l-kynurenine results in increased anxiety-like behaviours in mouse (Salazar et al., Reference Salazar, Gonzalez-Rivera, Redus, Parrott and O’Connor2012; Varga et al., Reference Varga, Herédi, Kànvàsi, Ruszka, Kis, Ono, Iwamori, Iwamori, Takakuwa, Vécsei, Toldi and Gellért2015) although whether l-kynurenine itself triggers the anxiety-like behaviours or if a downstream metabolite, such as QUIN, might be responsible has yet to be concretly determined. However, KMO knockout mice, which have elevated levels of brain kynurenine and KYNA but lower levels of QUIN than wildtype mice (Giorgini et al., Reference Giorgini, Huang, Sathyasaikumar, Notarangelo, Thomas, Tararina, Wu, Schwarcz and Muchowski2013), also display increased anxiety behaviour as well as other behavioural deficits (Erhardt et al., Reference Erhardt, Pocivavsek, Repici, Liu, Imbeault, Maddison, Thomas, Smalley, Larsson, Muchowski, Giorgini and Schwarcz2017a).

The timing of acute TDO2 administration was based upon the work of Salter et al. (Reference Salter, Hazelwood, Pogson, Iyer and Madge1995) indicating increased brain tryptophan and 5-HIAA 1 to 6 h and increased 5-HT 2–6 h following 680C91 administration per os in rat. We report here that 680C91 at a dose of 15 mg/kg also raises tryptophan levels in mouse following acute administration and that increased levels of tryptophan are sustained when the same dose of 680C91 is chronically administered. Whereas we did not detect a short-term elevation of 5-HT or 5-HIAA, elevation of 5-HIAA was observed after chronic treatment in the above experiments. Differences in short-term effects between our work and Salter’s could be due to type of administration (gavage vs. voluntary consumption) or different pharmacokinetics between species. However, in mice constitutively lacking TDO2, increases in brain Trp, 5-HT and 5-HIAA were also observed (Too et al., Reference Too, Li, Suarna, Maghzal, Stocker, McGregor and Hunt2016), and taken together with our and Salter’s study, it would seem loss of TDO2 shifts tryptophan metabolism towards the serotonergic pathway. At the dose used here, we observed a small effect of 680C91 that manifested itself as increased freezing during memory recall in contextual fear conditioning. Such a result can be interpreted as increased anxiety and could be caused by increased serotonergic activity (Frick et al., Reference Frick, Åhs, Engman, Jonasson, Alaie, Björkstrand, Frans, Faria, Linnman, Appel, Wahlstedt, Lubberink, Fredrikson and Furmark2015). However, 680C91 showed no anxiogenic effects of its own in the light–dark box and elevated plus maze, more traditional tests of anxiety-like behaviours in rodents. It is not surprising that one inhibitor can have differential effects on anxiety-like behaviours in different tests as anxiety can have many facets (Wiedemann, Reference Wiedemann, Smelser and Baltes2001; Campos et al., Reference Campos, Fogaça, Aguiar and Guimarães2013). However, it is possible that a different dose of 680C91 would have produced different effects and our results should be interpreted with caution as a dose–response curve was not performed. Nevertheless, considering the elevation of Trp and promotion of serotonergic signalling by 680C91 with little impact on behaviour, perhaps inhibition of TDO2 in the context of antidepressant action should be revisited.

Overall, this work shows that chronic oral administration of the IDO1 inhibitor 1-MT is successful in lowering kynurenine and the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio following LPS. Our study supports previous studies showing that IDO1 is a major player in kynurenine synthesis following LPS challenge. Furthermore, we show that TDO2 is likely not involved in this process and that TDO2 inhibition is not a viable option as concerns abrogating LPS-induced cognitive deficits, anxiety-like behaviours, and reducing kynurenine and the kynurenine:tryptophan ratio. Importantly, our results using group-housed mice suggests immune modulation from single-housing conditions as a possible contributing factor to previously observed behavioural effects.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2019.44

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Markus K. Larsson for help with tissue collection and Martina Andersson for excellent animal care.

Author’s contributions

SI planned and performed experiments, analysed data, and wrote the mauscript; MG performed HPLC, analysed the data, and edited the manuscript; XL performed experiments; SE planned experiments, edited the manuscript, and provided financial support.

Financial support

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Medical Research Council (2017-00875), the Swedish Brain Foundation, Märta Lundqvists Stiftelse, Petrus och Augusta Hedlunds Stiftelse, Torsten Söderbergs Stiftelse, and the AstraZeneca-Karolinska Institutet Joint Research Program in Translational Science.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Experiments were approved by and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Ethical Committee of Northern Stockholm, Sweden and in agreement with Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes.