Significant outcomes

The prefrontal cortex volumes possibly involved in suicidal ideation are related to the neuropathological changes seen in MDD.

The left DLPFC reductions correlate with MDD and suicidal ideation, and diminished GMV reductions in the right DLPFC and right VLPFC correlate with suicidal ideation.

Limitations

Several limitations in this study cannot be ignored. First, the effects of medications on brain structure and function were not ruled out. Although medications did not differ significantly with respect to the groups with MDD with and without suicidal ideation, it is unclear how antidepressants affect the risk of suicide (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Bschor, Franklin and Baethge2016). Thus, additional studies are needed to examine brain damage in medication-free MDD with suicidal ideation. Second, the diagnosis of MDD can be changed to bipolar disorder (BD), and this could affect the accuracy of the diagnoses, despite all included patients with MDD being followed up by telephone regularly for 1 year to determine whether their diagnosis had changed to BD. Longitudinal, large-sample experiments that explore the dynamic structural alterations in patients with MDD and suicidal ideation are needed to verify the findings of this study. Furthermore, we failed to explore the correlations between 17-item HAMD-17 scores and gray matter volumes, and future studies combining neuropsychological data are necessary to investigate structural brain alternations in individuals with MDD and suicidal ideation.

Introduction

In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) released a world health report that estimated that there are 322 million cases of depressive disorder in the world (WHO, 2017). Depression is predicted to become the second most common disease after heart disease by 2020 (WHO, 2001). Furthermore, as many as 15% of all patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) end their lives by suicide (Bland, Reference Bland1997), and the lifetime suicide risk of patients with MDD is estimated at approximately 30% (Radomsky et al., Reference Radomsky, Haas, Mann and Sweeney1999). Suicidal ideation, which is one of the main risk factors for suicide death (Gliatto & Rai, Reference Gliatto and Rai1999; Mann et al., Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier, Haas, Hegerl, Lonnqvist, Malone, Marusic, Mehlum, Patton, Phillips, Rutz, Rihmer, Schmidtke, Shaffer, Silverman, Takahashi, Varnik, Wasserman, Yip and Hendin2005), is generally associated with depression. Patients with MDD and suicidal ideation have a higher risk of suicide than the general population according to a research study that followed patients over 34–38 years (Angst et al., Reference Angst, Stassen, Clayton and Angst2002). In previous studies of suicide behaviour in depression, more researchers indeed indicate that many forms of suicide death may along a development path from suicidal ideation to completed suicide (Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010; Klonsky et al., Reference Klonsky, May and Saffer2016). Suicidal ideation is seen as a early indicator of evaluating suicide risk which is different from suicide attempts (Mann et al., Reference Mann, Waternaux, Haas and Malone1999; Klonsky et al., Reference Klonsky, May and Saffer2016). To date, many studies have shown that the presence of suicidal ideation in patients with MDD is associated with structural and functional abnormalities in multiple brain regions (Minzenberg et al., Reference Minzenberg, Lesh, Niendam, Cheng and Carter2016; Du et al., Reference Du, Zeng, Liu, Tang, Meng, Li and Fu2017), which suggests that neuroimaging methods can be used clinically to assess suicide risk. Unfortunately, the neurostructural alterations in MDD with suicidal ideation are not clear.

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) has been implicated in decision-making (Rushworth et al., Reference Rushworth, Noonan, Boorman, Walton and Behrens2011), impulsiveness (Bari & Robbins, Reference Bari and Robbins2013), and suppression of emotional responses (Goldin et al., Reference Goldin, McRae, Ramel and Gross2008), which generally constitute risk factors for suicidal behaviour (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang, Qiu, Xu and Jia2017). Moreover, extensive lines of evidence implicate that this brain region is also linked to depressive disorder. Several functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have linked abnormalities in PFC activity to patients with MDD (Walter et al., Reference Walter, Wolf, Spitzer and Vasic2007; Hsu et al., Reference Hsu, Langenecker, Kennedy, Zubieta and Heitzeg2010; Nixon et al., Reference Nixon, Liddle, Worwood, Liotti and Nixon2013). A structural MRI study has also indicated that, compared with comparison subjects and patients with schizophrenia, patients with MDD are more likely to have increased volume in the posterior subgenual PFC (Coryell et al., Reference Coryell, Nopoulos, Drevets, Wilson and Andreasen2005). Furthermore, studies of MDD with suicidal ideation have reported abnormal structures and/or activity in the PFC, mainly involving the striatal-anterior cortical midline circuits (Marchand et al., Reference Marchand, Lee, Johnson, Thatcher, Gale, Wood and Jeong2012), and the left and right ventrolateral PFC (VLPFC) (Minzenberg et al., Reference Minzenberg, Lesh, Niendam, Cheng and Carter2016). These results suggest that damage to brain areas such as the PFC, which is linked to emotions and cognition, contributes to poor decision-making and impulsivity in patients with MDD and might be key for understanding the underlying neuroanatomical differences in MDD with suicidal ideation or thoughts. Furthermore, even if recent neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that MDD with suicidal ideation is closely related to the PFC, few studies have specifically compared the structural differences in the PFC between patients with MDD with and without suicidal ideation to understand the function of different partitions within the PFC in MDD and suicidal ideation.

To examine the PFC volume in MDD with suicidal ideation, this study used a voxel-based morphometric analysis of T1-weighted images. We compared the differences in the gray matter volume (GMV) of the left and right PFC among individuals with MDD with and without suicidal ideation, and age- and gender-matched healthy controls (HCs). Our hypotheses were that (1) patients with MDD exhibit structural changes in the PFC and (2) several brain regions changes are present only in MDD with suicidal ideation and not in MDD without suicidal ideation.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 116 participants aged 15–46 years included 35 with MDD with suicidal ideation, 38 with MDD without suicidal ideation, and 43 matched HCs. The patients with MDD were recruited from the inpatient department of the Shenyang Mental Health Center and the outpatient clinic of the Department of Psychiatry of the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China. All patients with MDD were evaluated by the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV Axis I disorders for those 18 years and older and by the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version in those younger than 18. All patients were recommended for the group by two clinical psychiatrists and assessed as determining the presence or absence of Axis I psychiatric diagnoses by a trained psychiatrist. Patients were excluded if they had epilepsy, a history of alcohol/drug abuse or dependence, head trauma, history of a major physical or nervous system disease, any electroencephalography abnormalities, diabetes, thyroid disease, other medical history, or any MRI contraindications.

The HC subjects were recruited by advertisement and matched to the MDD group for age, gender, and academic year. The HC subjects did not have a current Axis I disorder, that is, history of psychotic mood, or other Axis I disorders in their first-degree relatives according to a detailed family history, or any abnormalities on brain images.

All participants signed a written consent form. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the first affiliated Hospital of China Medical University.

Clinical assessment

The severity of suicidal ideation (defined as fleeting thoughts, extensive thoughts, detailed planning, and/or incomplete attempts) was evaluated using the 19-item Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (for both ‘most severe ideation’ and ‘most recent ideation’) (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Kovacs and Weissman1979). All patients with MDD were divided into an MDD with suicidal ideation group and MDD without suicidal ideation group based on their scores on the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation. Any healthy subject who reported suicidal ideation was excluded from the HC group. Depression severity was assessed using the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-17). The total defined daily dose (http://www.whocc.no/) was calculated separately for antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilisers, and antianxiety drugs.

Handedness was assessed using the 10-item Chinese Handedness Inventory (writing, chopsticks, throwing, toothbrush, scissors, striking a match, putting thread through the eye of a needle, hammer, racket, washing used a towel) (Xin-tian, Reference Xin-tian1983). Answers were provided on a 2-point scale: 1 – always right to 0 – always left. An individual who is the preference for the right hand (the left hand) for the first six items and uses either hand for any of the last four items is called right handedness (left handedness), and one who uses one hand to do one to five of the first six items and uses the other hand to do the rest is said to be mixed handedness.

Image acquisition

The structural MRI scanning was conducted on a Signa HDx 3.0T superconductive MRI system (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) at the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China. Three-dimensional, high-resolution, and T1-weighted images were acquired using a three-dimensional fast spoiled gradient-echo sequence with the following parameters: repetition time/echo time, 7.2/3.2 ms; flip angle, 13°; image matrix, 240 × 240; field of view, 240 × 240 mm2; 176 contiguous 1-mm slices with a gap; and voxel size, 1.0 mm3. The subjects were required to stay awake, be quiet, remain in a prostrate position, relax with their eyes closed, and try not to think.

Data preprocessing

All structural MRI data were preprocessed using the voxel-based morphometry (VBM)8 toolbox (http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/vbm8/), which were incorporated into the Diffeomorphic Anatomic Registration Through Exponentiated Lie algorithm in the Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) software (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm8/; Welcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK) under the MATLAB R2011a platform (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). We used the standard procedures suggested by Ashburner and Friston (Reference Ashburner and Friston2000) to process the structural MRI data. The images were spatially normalised to the Montreal Neurological Institute space according to the default VBM8 parameters to obtain images with 1.5-mm3 voxels. The modulation process was performed using nonlinear deformations that are employed for normalisation and that allowed comparison of the absolute amount of tissue that was corrected for individual brain sizes. Finally, all images were smoothed with an isotropic Gaussian kernel of 8-mm full width at half maximum. Briefly, SPM8 was used to divide the regions into grey matter (GM), white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. The GM processed images were then used for the subsequent VBM statistical analysis.

Regions of interest definition

The Wake Forest University PickAtlas (http://fmri.wfubmc.edu/software/PickAtlas) was used to define the regions of interest of the PFC, including the Frontal_Sup, Frontal_Sup_Orb, Frontal_Mid, Frontal_Mid_Orb, Frontal_Inf_Oper, Frontal_Inf_Tri, and Frontal_Inf_Orb, in the left and right hemispheres based on an Automated Anatomical Labeling template in a digital human brain atlas that has been used in fMRI-based research and described by a French research group (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., Reference Tzourio-Mazoyer, Landeau, Papathanassiou, Crivello, Etard, Delcroix, Mazoyer and Joliot2002).

Statistical analyses

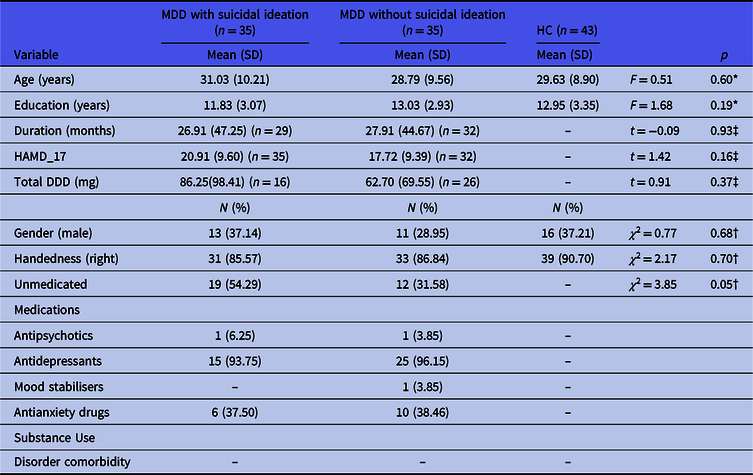

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (Armonk, NY, USA). Student’s t-tests, one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA), or Chi-square tests were used depending on the normality of the distribution and type of data. Categorical variables were described using frequencies and proportions. Continuous variables were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the three study groups

MDD, major depressive disorder; HC, healthy control; N/A, not applicable; HAMD_17, 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; DDD, defined daily dose.

The data are presented as n (%) or mean (standard deviation).

* One-way analysis of variance.

† Chi-square test.

‡ Student’s t-test.

The GMVs of the left and right PFC were compared among the groups by one-way ANOVA using SPM8. Group differences were considered significant for p values less than 0.001 [corrected, Gaussian random field (GRF) correction] and an extent threshold of 45 voxels. To further examine the differences between two groups, we extracted the GMVs for each cluster with significant differences for the three groups and then corrected for multiple comparisons (p < 0.05, least significant difference test).

For checking the effect of medication, a Student’s t-test was set up to detect the structure difference between medicated (taking medications for at least 8 weeks prior to scan) and unmedicated (medication naïve or no medication use for at least 4 weeks prior to the scan) individuals in the MDD with suicidal ideation group; similar analysis was to be done in the MDD without suicidal ideation group.

Results

Demographic and clinical results

The detailed demographic and clinical data of the participants are displayed in Table 1. The MDD with suicidal ideation group and MDD without suicidal ideation group did not differ significantly for medication (χ 2 = 3.85, p = 0.05), duration (t = −0.09, p = 0.93), and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score (t = 1.42, p = 0.16). In addition, age (F = 0.51, p = 0.60), gender (χ 2 = 0.77, p = 0.68), and educational years (F = 1.68, p = 0.19) did not differ among the three groups.

Comparisons within the three groups

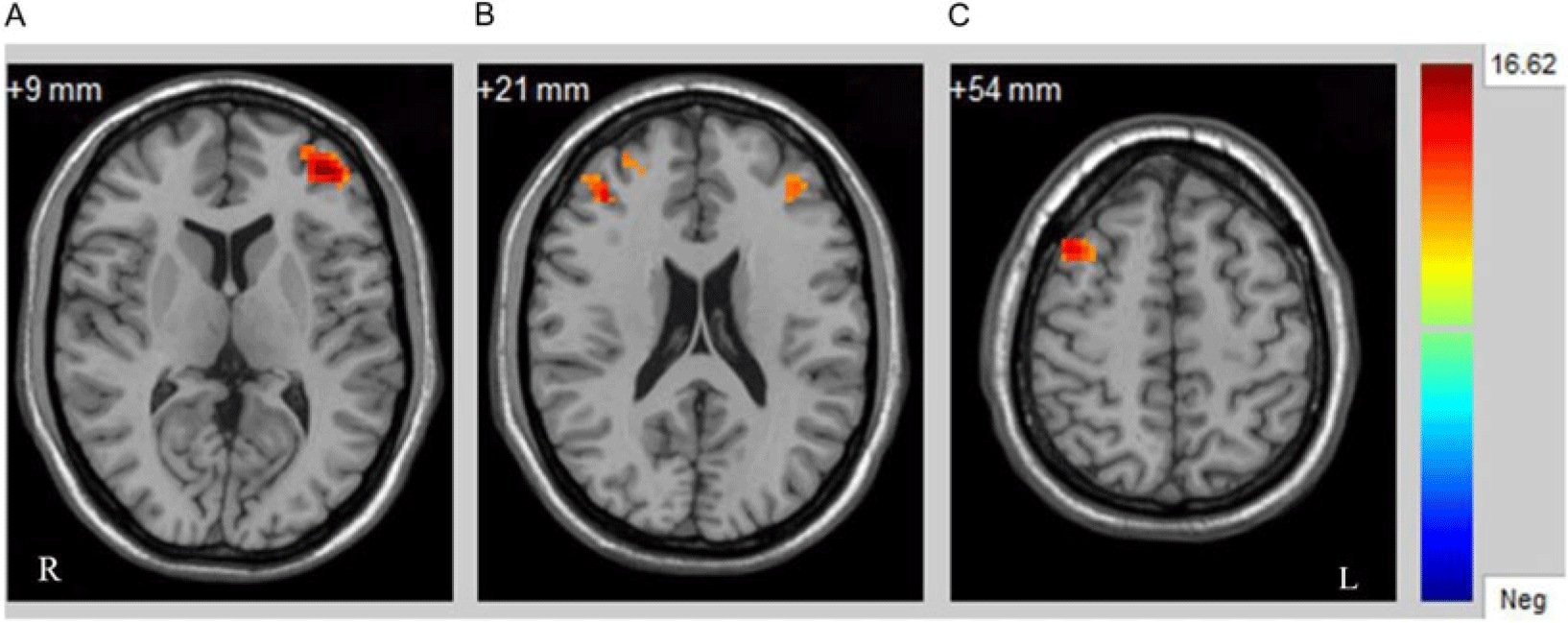

Significant differences in the GMV were found among the three groups in several regions, including the left and right dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC) and right VLPFC following a one-way ANOVA (p < 0.001, corrected; Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Table 2. Brain regions showing significant differences in volume in the three-group comparison

MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; DLPFC_L, left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; VLPFC_R, right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex; DLPFC_R, right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

Fig. 1. Significant differences in the GMV of the left and right PFC among the three groups. p < 0.001, GRF corrected. (A) Left dorsolateral PFC; (B) right ventrolateral PFC; (C) right dorsolateral PFC. Abbreviations: R, right; L, left.

To further determine which two groups differed significantly, we extracted GMVs from each cluster with significant differences for the three groups and compared them in pairs. The post hoc analyses showed that, in the left DLPFC, the MDD with suicidal ideation group had significantly decreased GMV compared with the GMVs of the MDD without suicidal ideation and HC groups; furthermore, the MDD without suicidal ideation group had significantly decreased GMV compared with the GMV of the HC group. For the right VLPFC and right DLPFC, the MDD with suicidal ideation group had significantly decreased GMV compared with that of other two groups, which was expected. However, no significant differences were found in these two brain regions between the MDD without suicidal ideation and HC groups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Post hoc analysis of the brain regions with significant differences among the three groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, least significant difference test.

Within the MDD with suicidal ideation group, no significant difference could be detected between medicated and unmedicated (p > 0.001, GRF correction); there were also no significant differences regarding this parameter in the MDD without suicidal ideation group (p > 0.001, GRF correction).

Logistic regression models supported decreased GMVs in the left DLPFC and were related to predicting the presence of suicidal ideation. But, these associations between GMVs in the right DLPFC and right VLPFC and suicidal ideation were not confirmed using logistic regression models. Other confounders including severity of depression and medication statues did not have a significant impact on the presence of suicidal ideation (Supplemental Materials).

Correlations between GMV and symptom scores

Furthermore, the present study could not find any significant correlations between the HAMD-17 scores and the GMV in regions that showed significant differences both in the MDD with suicidal ideation group and in the MDD without suicidal ideation group (p > 0.05, Pearson correlation analysis).

Discussion

This study was designed to analyse and compare the GMV of the left and right PFC in patients with MDD with and without suicidal ideation. Our analysis showed that, compared with HC subjects, those with MDD with suicidal ideation had significantly decreased GMV in the left and right DLPFC and right VLPFC, but only the GMV of the left DLPFC, and not the regions in the right hemisphere, was significantly decreased in patients with MDD without suicidal ideation. With regard to these data, we found no significant correlations between GMV reductions in these regions and HAMD-17 scores, likely for the reason that our sample size was not large enough. Further research with larger samples is needed to more definitively investigate the association between neuroimaging parameters and symptoms.

In addition, after controlling for confounding such as severity of depression and medication status in the logistic regression analysis of the present study, we did not find confounding have an impact on our result. However, the interpretation of confounding is too complicated to explain clearly in a simple adjustment because there is also a risk of ‘residual confounding.’ Still, these results suggest powerful neuropathological changes for structural alterations of suicidal ideation in patients with MDD.

We found that MDD with suicidal ideation exhibited decreased volumes in the right DLPFC and right VLPFC compared with those of MDD without suicidal ideation and HCs; but the two brain regions did not differ significantly between the group with MDD without suicidal ideation and HCs. The right DLPFC is involved with negative emotional judgement (Ueda et al., Reference Ueda, Okamoto, Okada, Yamashita, Hori and Yamawaki2003) and cognitive control (Nitschke & Mackiewicz, Reference Nitschke and Mackiewicz2005), and generally, abnormal activation and alterations of the right DLPFC would contribute to a disability in emotional processing (Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Rubinsztein, Sahakian and Dolan2002; Nitschke et al., Reference Nitschke, Heller, Etienne and Miller2004). In addition, the role of the right VLPFC is response inhibition (Aron et al., Reference Aron, Robbins and Poldrack2014). Accordingly, we speculated that the subjects with decreased GMV in the right DLPFC and right VLPFC inefficiently process negative emotions and respond poorly to dangerous behaviours, which results in hopeless thoughts and acts in these subjects when something terrible happens. Therefore, patients with MDD who have decreased GMVs of the right DLPFC and right VLPFC are at a greater risk for suicidal ideation. These findings are consistent with the results of a quantitative electroencephalographic study (Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Leuchter, Cook and Abrams2010) with the conclusion that right frontal lobe injuries are closely linked to MDD with suicidal ideation. Another fMRI study of combat-exposed war veterans reported that suicidal ideation is associated with increased frontal error-related activation (Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Spadoni, Knox, Strigo and Simmons2012). Network-based statistics and graph theoretical analyses have shown that the white matter connectivity in frontal–subcortical circuits in the left hemisphere is related to the intensity of suicidal ideation and impulsivity (Myung et al., Reference Myung, Han, Fava, Mischoulon, Papakostas, Heo, Kim, Kim, Kim, Kim, Seo, Seong and Jeon2016). These studies support the usefulness of our analyses, which confirmed that GMV reductions in the two regions may be linked to the presence of suicidal ideation, and consequently produces strong evidence of the importance of the frontal system in suicidal ideation.

We additionally observed that all patients with MDD had significantly decreased GMV in the left DLPFC, which plays an important role in positive emotional judgement (Ueda et al., Reference Ueda, Okamoto, Okada, Yamashita, Hori and Yamawaki2003). Furthermore, the MDD with suicidal ideation group had a greater decrease in the GMV of the left DLPFC compared with the MDD without suicidal ideation group, which indicates that the left DLPFC may not only be closely associated with the disorder, but also is related to suicidal ideation. Studies have shown impairments in this region in patients with MDD and individuals at high risk for MDD (Hugdahl et al., Reference Hugdahl, Rund, Lund, Asbjornsen, Egeland, Ersland, Landro, Roness, Stordal, Sundet and Thomsen2004; Frodl et al., Reference Frodl, Reinhold, Koutsouleris, Reiser and Meisenzahl2010; Amico et al., Reference Amico, Meisenzahl, Koutsouleris, Reiser, Moller and Frodl2011). Moreover, an fMRI study has reported that further decreased GMV of the left DLPFC represents weak positive emotion, which might be why patients with MDD have smaller GMV in the left DLPFC (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Mao, Wei, Yang, Du, Xie and Qiu2016). We therefore thought that the decreased GMV in the left DLPFC might have resulted from the pathogenesis of MDD, which was consistent with the discussion in a previous critical review (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Drevets, Rauch and Lane2003). In the studies about suicidal behaviour, prior fMRI studies also have suggested that abnormalities in the left DLPFC are associated with that behaviour. For instance, a recent neuroimaging replication study found that 15 euthymic suicide attempters with a history of depression had a decreased response to risky versus safe choices in the left dorsal PFC (DPFC), which might have resulted from a dysfunctional DPFC receiving inadequate information, which then led to adverse choices (Olie et al., Reference Olie, Ding, Le Bars, de Champfleur, Mura, Bonafe, Courtet and Jollant2015). A large-sample study directly compared the brain structures of euthymic suicide attempters with a history of mood disorders and suicidal behaviour (N = 67), patient controls with a history of mood disorders but not suicidal behaviour (N = 82), and healthy subjects without a history of a mental disorder (N = 82), and found decreased measures in the left DPFC in suicide attempters (Ding et al., Reference Ding, Lawrence, Olie, Cyprien, le Bars, Bonafe, Phillips, Courtet and Jollant2015). More importantly, both repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and deep transcranial magnetic stimulation studies have confirmed that targeting the left DLPFC stimulation site significantly decreases suicidal ideations (Berlim et al., Reference Berlim, Van den Eynde, Tovar-Perdomo, Chachamovich, Zangen and Turecki2014; Desmyter, et al., Reference Desmyter, Duprat, Baeken, Bijttebier and van Heeringen2014). The above studies support the importance of the involvement of the structure of the left DLPFC in suicidal ideation and MDD. However, it is not clear whether the abnormal left DLPFC GMV reductions in MDD with suicidal ideation are a pathological change in different subtypes of MDD, and therefore, this merits further study.

Nonetheless, the study is different from others in some findings. Wagner et al. observed GMV and cortical thickness separately using the same data in 2011 (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Koch, Schachtzabel, Schultz, Sauer and Schlosser2011) and 2012 (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Schultz, Koch, Schachtzabel, Sauer and Schlosser2012) and reported alterations in the left DLPFC and VLPFC in patients with MDD with suicidal ideation, but failed to observe significantly decreased GMV in patients with MDD without suicidal behaviour compared to the HC group, partly in conformity with our study. One possible explanation is the different clinical and demographical features from different countries. Diffusion tensor imaging from China (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Wang, Huang, Kuang, Wu, Lui, Sweeney and Gong2014) confirmed that the alteration in the orbitofrontal cortex and thalamic regions in patients with suicide attempts may reflect abnormalities related to both MDD and suicide attempts, which further supports the present study. Thus, even if a few studies were inconsistent with our findings, our study presents new evidence to support the hypothesis that structural abnormalities seen with neuroimaging are associated with MDD and suicidal ideation. Furthermore, combining volumetric methods and cortical thickness or other flexible algorithms is necessary to explore the specific changes in patients with MDD with suicidal ideation, and this will become a study emphasis in our further research.

There are available sources indicated that both biological and environmental factors impact on the aetiology of suicidal ideation in patients with MDD. Some studies approved that the aetiology of suicidal ideation is related to gene expression including involvement of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor-neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase-cAMP responsive element binding protein pathway (Pulay & Rethelyi, Reference Pulay and Rethelyi2016; Bozorgmehr et al., Reference Bozorgmehr, Alizadeh, Ofogh, Hamzekalayi, Herati, Moradkhani, Shahbazi and Ghadirivasfi2018), the level of heterotrimeric G proteins (Gonzalez-Maeso & Meana, Reference Gonzalez-Maeso and Meana2006), low central nervous system serotonin level (van Heeringen, Reference van Heeringen2003), and high triglyceride level and elevated fasting plasma glucose level (Ko et al., Reference Ko, Han, Shin, Lee, Han, Kim, Yoon and Ko2019). In addition, recent epidemiological investigation also showed that environment factors may be at work in the aetiology of suicidal ideation such as unhealthy family environment, low standard of living, and stressful life events in the preceding 12 months (Dutta et al., Reference Dutta, Ball, Siribaddana, Sumathipala, Samaraweera, McGuffin and Hotopf2017). To date, there has been no consistent conclusion about the aetiology of suicidal ideation in patients with MDD, so that the clinical manifestations of suicidal ideation are also complex. Suicide ideation manifests a variety of behavioural phenomena such as overaroual (Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Tucker, Law, Michaels, Anestis and Joiner2016), anhedonia, and pain avoidance motivation (Xie et al., Reference Xie, Li, Luo, Fu, Ying, Wang, Yin, Zou, Cui, Wang and Shi2014).

Indeed, suicide ideation is resulted from multidetermined factor. The importance of biological, psychodynamics, and social factors as determinants of suicide is well established (Botsis et al., Reference Botsis, Soldatos and Stefanis1997). In a psychological perspective, Horwitz and colleagues have suggested that patients with MDD and suicidal ideation tend to show hopelessness (Horwitz et al., Reference Horwitz, Berona, Czyz, Yeguez and King2017). Another recent study supports that anhedonia is useful for predicting suicidal ideation (Winer et al., Reference Winer, Nadorff, Ellis, Allen, Herrera and Salem2014). Besides, observed findings also confirmed the links between negative emotions (Kiosses et al., Reference Kiosses, Gross, Banerjee, Duberstein, Putrino and Alexopoulos2017), problem solving (Abdollahi et al., Reference Abdollahi, Talib, Yaacob and Ismail2016), rumination (Teismann & Forkmann, Reference Teismann and Forkmann2017), and suicidal ideation. Secondly, the social factors that are closely related to suicidal ideation in depression include demographic factors, family characteristics and childhood experience, and environmental factor (e.g. stress and frustration in life) (Aaltonen et al., Reference Aaltonen, Naatanen, Heikkinen, Koivisto, Baryshnikov, Karpov, Oksanen, Melartin, Suominen, Joffe, Paunio and Isometsa2016; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Xu, Gu, Lau, Hao, Zhao, Davis and Hao2016; Buckner et al., Reference Buckner, Lemke, Jeffries and Shah2017). From a biological perspective, abnormalities in the serotonergic (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) system (Picouto et al., Reference Picouto, Villar and Braquehais2015), dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (Ghaziuddin et al., Reference Ghaziuddin, King, Welch and Ghaziuddin2014), and a genetic contribution (Kang et al., Reference Kang, Bae, Kim, Shin, Hong, Ahn, Jeong, Yoon and Kim2017) to the risk of suicide have been found. Based on neuroimaging perspective, the present study observed that the left DLPFC GMV reductions as a biological factor may play a role in suicidal ideation in depression.

In summary, we showed that alterations of the right VLPFC and right DLPFC are related to suicidal ideation, while the left DLPFC GMV reductions may reflect abnormalities related to MDD and suicidal ideation; this further provides strong evidence showing that structural abnormalities in the PFC may disrupt emotional processing and inhibition, leading to a high risk of suicide and MDD.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2019.45.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants who took part in this study. The support to recruitment by personnel in Shenyang Mental Health Center and the Department of Psychiatry of the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University is acknowledged. In addition, we thank Elsevier service for professional language editing.

Authors contributions

RZ conceived, designed, and coordinated the study and drafted the manuscript. SW supported data collection and contributed to drafting the manuscript. MC and XJ collected data. YT and FW supported data collection and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81701336 to SW, 81571311, 81071099 and 81271499 to YT, 81725005, 81571331 to FW), National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFC1306900 to YT), the Liaoning Education Foundation (L2015591 to SW), Liaoning Education Foundation (Pandeng Scholar, FW), National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFC0904300 to FW), and National High Tech Development Plan (863) (2015AA020513 to FW).

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.