1 Introduction

The study of belief and its norms of rationality is a central part of contemporary epistemology. But belief is just one of many doxastic states. When it comes to the class of doxastic states, epistemologists commonly distinguish between our outright doxastic states and our degreed doxastic states. The outright doxastic states include believing that p, thinking that p, having the opinion that p, being sure that p, being certain that p, and doubting that p. Our degreed doxastic states include degrees of confidence, credences, and certain degreed phenomenal states.

However, in addition to the outright doxastic states mentioned above we also have conviction, that is, the state of being convinced (simpliciter) that something is the case. And in addition to the degreed states mentioned in the previous paragraph we have degrees of conviction, that is, being more or less convinced that something is the case. The concept of conviction was central to Kant’s way of thinking about our doxastic states. However, conviction has not been regarded as a distinctive doxastic mental state in recent philosophy of mind and epistemology. The aim of this Element is to locate and defend the distinctive place of conviction and its degrees among our doxastic states.

When it comes to our doxastic states there are two kinds of questions we can ask. We can ask questions about their nature:

Nature Question. For any agent S and doxastic state D, what is it for S to be in state D?

But we can also ask questions about their structure:

Structural Question. For any doxastic states D1 … Dn, how are D1 … Dn related to each other?

Section 2 begins with a suggestive Kantian answer to the Structural Question. It then provides evidence for a version of a Kantian picture on which we have at least three outright doxastic states, where thinking is the logically weakest state, certainty is the logically strongest state, and conviction stands between them. A version of Foley’s (Reference Foley1992) reductive Lockean approach to our outright doxastic states is considered. On this view, we can account for all our outright doxastic states in terms of confidence thresholds. This view is rejected, owing to the psychological possibility of having a very high degree of confidence in p while failing to believe, or think, or be convinced that p.

Section 3 provides an alternative view. It demonstrates the foundations for thinking that conviction comes in degrees and shows how degrees of conviction provide what is needed for a distinctive Kantian Threshold View of our outright doxastic states. For some readers, the Kantian Threshold View will not appear very different from its Lockean counterpart. This is likely owed to the following presupposition:

Conviction–Confidence Identity. Degrees of conviction just are degrees of confidence.

But this presupposition is plagued with problems. However, to appreciate these problems we first need to answer the Nature Question in regard to degrees of conviction. Section 4 does this, arguing that one’s degree of conviction in p is, roughly, the strength of one’s disposition to rely on p.

Section 5 defends the sui generity of degrees of conviction. In particular, this section explains how and why degrees of conviction separate from degrees of confidence (credences) and other degreed doxastic states, including felt degrees of confidence, the feeling of conviction, and degrees of revisability. It also provides an ecumenical suggestion about how best to understand talk of ‘degrees of belief’.

Section 6 uses facts about masking dispositions to explain how and why we can simultaneously believe (/think, /be convinced, /be certain) that p while also suspending these very states. This is a significant result as it’s usually assumed that suspending an attitude necessarily involves lacking that attitude; that is, believing that p and suspending belief that p are incompatible. This incompatibilist idea is central to many epistemic problems and has been used to motivate dilemmas of rationality. But if belief and the suspension of belief are compatible states, then once-paradoxical cases arguably cease to be paradoxical.

Section 7 turns to historical questions about the extent to which Kant was himself a ‘Kantian’ in our sense. It turns out that Kant’s theory of doxastic states was surprisingly Kantian as he prominently discusses conviction simpliciter and occasionally comments on degrees of conviction. Further, there is some evidence that Kant thought about states such as opinion and certainty in terms of degrees of conviction. Lastly, Kant’s concept of degrees of conviction is open to (or at least not in tension with) the dispositional analysis of degrees of conviction.

2 Conviction and Its Doxastic Neighbourhood

Belief is the paradigmatic outright doxastic state, and many studies of our outright doxastic states start with belief. This study is different. It begins with a summary of Kant’s views about the outright doxastic states, which motivates an exploration of a body of linguistic evidence for the idea that we have at least three distinct outright doxastic states that involve taking a positive stance towards a proposition: thinking, conviction, and certainty. Reflection on Kant’s theory of assent motivates the idea that these are strength-ordered in the following way: thinking is the logically weakest state (entailing none of the others), certainty the logically strongest state (entailing all of the others), and conviction stands between (entailing only itself and thinking). We explain why a Lockean Threshold View cannot account for these structural facts, and in the following section we introduce a Kantian Threshold View.

2.1 A Kantian Approach to the Doxastic Attitudes

This section quickly introduces one interpretation of Kant’s understanding of our fundamental doxastic states that stands out to us for the simple reason that it provides the starting point for a promising way of approaching the nature of the outright doxastic states and their relation to degreed doxastic states in philosophy of mind and epistemology.

When it comes to our doxastic states Kant introduces a central and organizing doxastic concept that he calls Fürwahrhalten, which literally means ‘holding to be true’, but is more commonly translated as ‘assent’. Assent, as a genus, should be thought of as a purely doxastic state and one that sits atop a gothic taxonomy with many species and subspecies that are individuated by various further characteristics (A820–31/B848–59).Footnote 1 To begin to get a grip on this taxonomy, consider any arbitrary case in which an agent assents to p. Kant suggests that of any case of assent we can ask at least the following questions:

Normative Questions. Is the agent’s state of assent justified by the agent’s grounds/reasons to any degree? If so, is there a sufficient degree of justification for being in that state? Is the justification in question provided by evidential and/or non-evidential grounds/reasons?Footnote 2

Voluntaristic Questions. Did the agent come to assent to p just by choosing to do so? That is, is the agent’s state of assent within their direct voluntary control?Footnote 3

Doxastic Question. How strong is the agent’s state of assent? That is, how strongly does the agent take p to be true?

Kant derives different species of assent based on how these questions get answered. For example, knowledge (Wissen) is a species of assent for Kant that requires assenting to p in response to sufficient evidential grounds, where these grounds force one to assent to p and thus put one’s assent outside of one’s direct voluntary control.Footnote 4 And knowledge, for Kant, additionally involves the strongest degree of assent. Faith (Glaube) is another species of assent for Kant, which requires assenting to p on sufficient non-evidential, practical grounds. Unlike knowledge, faith is within one’s direct voluntary control. But, like knowledge, faith for Kant requires the strongest degree of assent.Footnote 5

However, while most species of assent respond to all three questions, Kant occasionally also identifies instances of assent that only respond to the Doxastic Question. These species of assent involve purely doxastic attitudes that can be characterized by differences in their strength. Put differently, Kant seems to have recognized that agents can assent more or less strongly, and that this feature of a state of assent can be described independently of its normative and voluntaristic features. These doxastic states have been largely ignored in the recent literature on Kant’s theory of assent, mainly because they don’t feature prominently in the standard taxonomy. Yet they are the ones we’ll be focusing on.

Kant identified three kinds of assent in relation to how strong one’s state of assent could be. First among these is certainty (Gewissheit) or more precisely what Kant calls ‘subjective certainty’ (24:437). Subjective certainty arguably aligns with what we now call ‘psychological certainty’ and indicates the strongest state of assent.Footnote 6 Next is Kant’s notion of conviction (Überzeugung), specifically his notion of ‘subjective conviction’ (A824/B852). This consists of a strong – Kant uses the term ‘firm’ (A824/B852) – state of assent. Weaker than both of them is opinion (Meinung). Opinion is a bit tricky because Kant also defines it with reference to the Normative Question and its degree of evidential support (A822/B850). But insofar as the strength of opinion is proportional to its evidence,Footnote 7 we can bracket this normative dimension and focus entirely on opinion as a weak state of assent, which one might call ‘subjective opinion’ to keep with Kant’s naming scheme. On Kant’s account, there is no weaker state of assent than subjective opinion.Footnote 8 Since what follows is just about our doxastic states, we will drop the ‘subjective’ qualifier. Putting a picture to these strength-ordered states of assent, we have Figure 1.

Figure 1 Taxonomy of strength-ordered assent.

There is much more to say about this interpretation of Kant’s theory of assent and its relation to contemporary ways of thinking about our doxastic states. We’ll return to this in Section 7. For now these quick remarks on Kant inspire new ways of approaching the structural relations that obtain among our doxastic states. First of all, it is somewhat uncommon for epistemologists to theorize about opinion, but opinions are among our doxastic states. Second, it is especially uncommon for epistemologists to theorize about conviction, that is, the state of being convinced. But it too is among our doxastic states. Third, it is somewhat uncommon to seek to organize our outright doxastic states as standing in something like a genus–species relation (or, at the very least, a generality relation), where the most general outright state entailed by all the other more specific states involves the idea of ‘holding a proposition as true’. But in what follows we will argue that this broadly Kantian picture of our outright doxastic states is correct.

2.2 Natural Language on Thinking, Conviction, and Certainty

Linguistic evidence supports the Kantian idea that our folk theory of mind references at least three distinct outright doxastic states that admit a strength-ordering involving opinion/thinking, conviction, and certainty. This idea runs contrary to an emerging line of thought that natural language (or at least English) makes no reference to any outright doxastic state that stands between thinking and certainty.Footnote 9 If correct, there is no outright doxastic state that stands between thinking and certainty in terms of strength.Footnote 10 But what has been overlooked is conviction. And it is not hard to see that conviction has a distinctive place in our economy of doxastic states.

To begin to see this, take the following expressions, which ascribe outright doxastic states to agents:

(1) S thinks that p. / It is S’s opinion that p.

(1′) S denkt, dass p. / Es ist S’ Meinung, dass p.

(2) S is convinced that p.

(2′) S ist (davon) überzeugt, dass p.

(3) S is certain that p.

(3′) S ist (sich) gewiss, dass p.

Expressions (1)–(3′) are a familiar part of everyday thought and talk. The task to follow is to explore their relational features.

The first thing to highlight is that ‘S thinks that p’ (‘S denkt, dass p’) and ‘It is S’s opinion that p’ (‘Es ist S’ Meinung, dass p’) are expressions that seem to refer to the same doxastic state in both English and German. Consider separating them:

(4) ?He thinks that she arrived, but it’s not his opinion that she arrived.

(4′) ?Er denkt, dass sie angekommen ist, aber es ist nicht seine Meinung, dass sie angekommen ist.

(5) ?It’s his opinion that she arrived, but he does not think that she arrived.

(5′) ?Es ist seine Meinung, dass sie angekommen ist, aber er denkt nicht, dass sie angekommen ist.

These strike us as not only odd-sounding, but also as semantically infelicitous. Should that be so, we will have strong evidence for the following identity:

T=O Necessarily, S thinks that p iff it is S’s opinion that p.

Notwendigerweise gilt, S denkt, dass p, genau dann, wenn es S’ Meinung ist, dass p.

But not all are happy with T=O. Some informants report that ‘It’s her opinion that p’ carries information about the weakness of one’s evidential position in regard to p. We think this is a pragmatic implicature where the term ‘just’ is typically heard implicitly and is taken to convey something about the weakness of one’s evidential position, as in ‘It’s just her opinion that p’. This implicature can also be provoked by adding ‘just’ to thinking claims, as in ‘She just thinks that p’. Arguably, hearing the silent ‘just’ is a result of an expectation that speakers conform to the Gricean maxim of quantity: be as informative as one can, and give just as much information as is needed for current conversational aims. For, typically, if one is as informative as is relevant and one is convinced/certain that p, one will not indicate only that it’s one’s opinion that p. Further, the sense of evidential weakness associated with opinion comes from the expectation that rational agents proportion their doxastic attitudes to their evidence. Thus, if one just has the opinion (/just thinks) that p, this would suggest that one’s evidence isn’t strong enough for being convinced or certain.Footnote 11 We emphasize: nothing turns on T=O in Sections 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. So we’ll sidestep the issue of T=O by privileging ‘thinks that’ in what follows. We leave it to those who disagree with T=O to say what opinion is and how it differs from thinking-that.

When it comes to discussions of certainty it is standard to distinguish epistemic certainty from psychological certainty, where ‘psychological certainty’ refers to whatever doxastic state is implicated by the expression ‘S is certain that p’. In contrast, ‘epistemic certainty’ is widely used to refer to whatever condition the expression ‘It is certain that p’ refers to. In what follows we are only concerned with psychological certainty.

It is clearly possible to think that something is true while not being certain that it is. We think a friend will visit today because they said so. But we aren’t certain that they will since transportation strikes are not unusual in Cologne. Thus, we have:

T1 It is possible that S thinks that p, but S is not certain that p.

Es ist möglich, dass S denkt, dass p, aber S (sich) nicht gewiss ist, dass p.

Additionally, we may observe that certainty entails thinking. That is:

T2 Necessarily, if S is certain that p, then S thinks that p.

Notwendigerweise gilt, wenn S (sich) gewiss ist, dass p, dann denkt S, dass p.

Were T2 false, statements like the following should sound fine:

(6) #I’m certain that he arrived, but I don’t think that he arrived.

(6′) #Ich bin (mir) gewiss, dass er angekommen ist, aber ich denke nicht, dass er angekommen ist.

(7) #She’s certain that he arrived, but she doesn’t think that he arrived.

(7′) #Sie ist (sich) gewiss, dass er angekommen ist, aber sie denkt nicht, dass er angekommen ist.

But they sound far from fine, and T2 explains their infelicity.

Let’s bridge conviction and thinking. By ‘conviction’ we always mean to be referring to the state of being convinced. This is not unnatural. For when the noun ‘conviction’ is used with a sentential complement – ‘conviction that’ – it tends to be used to refer to the same state that the adjectival expression ‘convinced that’ does. Some dictionaries inter-define these expressions.Footnote 12 It does not matter for the present purposes whether the noun phrase ‘conviction that’ has other uses in natural language that refer to some other kind of doxastic state. For we will always work with the adjectival expression ‘convinced that’ and we use ‘conviction’ as a convenient noun to refer to the state of being convinced.Footnote 13

In regard to conviction and thinking, it is evident that conviction entails thinking:

T3 Necessarily, if S is convinced that p, then S thinks that p.

Notwendigerweise gilt, wenn S (davon) überzeugt ist, dass p, dann denkt S, dass p.

As evidence for T3 consider claims like:

(8) #I am convinced that he arrived, but I don’t think that he arrived.

(8′) #Ich bin (davon) überzeugt, dass er angekommen ist, aber ich denke nicht, dass er angekommen ist.

(9) #She is convinced that he arrived, but she doesn’t think that he arrived.

(9′) #Sie ist (davon) überzeugt, dass er angekommen ist, aber sie denkt nicht, dass er angekommen ist.

These don’t make sense. Plausibly, this is because conviction entails thinking.

The last entailment we wish to highlight is that certainty entails conviction:

T4 Necessarily, if S is certain that p, then S is convinced that p.

Notwendigerweise gilt, wenn S (sich) gewiss ist, dass p, dann ist S (davon) überzeugt, dass p.

Again, we find evidence for T4 by considering the oddity of instances that run contrary to it:

(10) #I am certain that he arrived, but I am not convinced that he arrived.

(10′) #Ich bin (mir) gewiss, dass er angekommen ist, aber ich bin nicht (davon) überzeugt, dass er angekommen ist.

(11) #She is certain that he arrived, but she is not convinced that he arrived.

(11′) #Sie ist (sich) gewiss, dass er angekommen ist, aber sie ist nicht (davon) überzeugt, dass er angekommen ist.

The readiest explanation for the contradictory sound of these is T4.

Thinking is not just logically weaker than conviction and certainty (in the sense that it entails neither); it seems normatively weaker (in the sense that it’s less evidentially demanding). Let’s illustrate this:

Track Race. Take a three-horse race. You know that horse A is more likely to win than horses B and C. You know the probability of A winning is 52%, and of B winning is 24%, and of C winning is 24%. When asked who you think will win, you answer: ‘I think horse A will win’ – all the while knowing that there is a very good chance that A will not win.Footnote 14

Cases like Track Race are quite ordinary and quite easily constructed:

Diagnosis. Dr House is treating a patient Sarah in New York with symptoms that are common to five different diseases: A–E. However, House knows that A is not uncommon in New York, but B–E are somewhat uncommon in New York – they are diseases that are usually contracted outside city environments and Sarah rarely travels outside the city. The probabilities of A–E are: Pr(A) = 0.52, Pr(B) = Pr(C) = Pr(D) = Pr(E) = 0.12. When asked to identify Sarah’s disease, House answers: ‘I think she has disease A.’Footnote 15

Many have argued that one need not speak falsely nor need one manifest any irrationality when claiming that ‘I think horse A will win’ or ‘I think she has disease A’ so long as these outcomes are sufficiently more likely than all their competitor outcomes. Indeed, some think that the probability of the accepted outcome can be less than 0.5.Footnote 16 But here lies a controversy we need not engage. We will limit ourselves to the following lesson:

T5 There are at least some cases where it is rational for S to think that p even if S knows that: while p is more likely than ¬p, ¬p is almost as likely as p.

Es gibt zumindest einige Fälle, in denen es für S rational ist, zu denken, dass p, selbst wenn S weiß, dass p zwar wahrscheinlicher ist als ¬p, aber ¬p fast so wahrscheinlich ist wie p.

Cases like Track Race and Diagnosis not only provide evidence for the normative weakness of thinking, but also its logical weakness relative to conviction. For example, an agent in Track Race might well think that A will win without being convinced that A will win. It would not be incoherent or surprising to hear an agent say in such a case: ‘I think that A will win, but I’m not convinced.’ This suggests:

T6 It is possible that S thinks that p, but S is not convinced that p.

Es ist möglich, dass S denkt, dass p, aber S nicht (davon) überzeugt ist, dass p.

An additional piece of evidence for T6 stems from the phenomenon of neg-raising associated with weak mental state terms. When we say ‘S doesn’t think that p’ we tend to provoke the implicature that ‘S thinks that not-p’. For example, uses of ‘You don’t think that she’s home’ suggest that ‘You think that she’s not home’. In contrast, this doesn’t occur with strong mental state terms like ‘certain’ and ‘sure’: stating that someone isn’t certain that p does not suggest that they are certain that ¬p.Footnote 17 ‘Convinced’ functions like ‘certain’ in regard to neg-raising: uses of ‘You’re not convinced that she’s home’ does not suggest that ‘You are convinced that she’s not home’. If the neg-raising behaviour of ‘thinks’ and the absence of such behaviour with ‘certain’ is evidence that thinking can separate from certainty, then we have the same kind of evidence for the idea that thinking can separate from conviction.

While intuitions about the rationality of thinking in cases like Track Race and Diagnosis provide some evidence that thinking is normatively weak, they provide no evidence that conviction or certainty are normatively weak. We cannot, without introducing a significant degree of irrationality, add to Track Race that you are either convinced or certain that horse A will win:

(12) While the evidence ensures that A is more likely to win than to lose, it also ensures that A is almost as likely to lose. So I’m convinced (/certain) that A will win.

(12′) Die HinweiseFootnote 18 stellen zwar sicher, dass A wahrscheinlicher gewinnt als verliert, aber sie stellen auch sicher, dass A fast genauso wahrscheinlich verliert. Ich bin also (davon) überzeugt (/(mir) gewiss), dass A gewinnen wird.

These statements sound problematic. Not because they represent psychological impossibilities, but because they each involve a non-trivial measure of irrationality. This suggests:

T7 It is irrational for S to be convinced that p or certain that p if S knows that: while p is more likely than ¬p, ¬p is almost as likely as p.

Es ist irrational für S, (davon) überzeugt zu sein, dass p oder (sich) gewiss zu sein, dass p, wenn S weiß, dass p zwar wahrscheinlicher ist als ¬p, aber ¬p fast so wahrscheinlich ist wie p.

Lastly, we note that conviction can separate from certainty:

T8 It is possible that S is convinced that p, but S is not certain that p.

Es ist möglich, dass S (davon) überzeugt ist, dass p, aber S (sich) nicht gewiss ist, dass p.

Examples are not hard to provide here. I am convinced that the Phoenicians were skilled sailors because I seem to remember my Roman history professor, Gary Ferngren, asserting this. But reflecting on the fallibility of historical evidence for events long past and my very limited historical knowledge, I would also say that I’m not certain of this. Similarly, I’m now convinced that my bike has not been stolen from my apartment basement. But knowing that all kinds of people have access to my apartment basement I would not say that I’m certain of this.Footnote 19 In general, when we are inclined to explicitly note that our evidence for p is very strong and yet fallible in a way that is worth not completely ignoring, statements of the following form sound just fine:

(13) ✓I am convinced that p, but I am not certain that p.

(13′) ✓Ich bin (davon) überzeugt, dass p, aber ich bin (mir) nicht gewiss, dass p.

Let’s now take stock. We’ve said nothing about belief. We’ll get to that. About thinking, conviction, and certainty, the following set of claims are well supported:

T1 It is possible that S thinks that p, but S is not certain that p.

T2 Necessarily, if S is certain that p, then S thinks that p.

T3 Necessarily, if S is convinced that p, then S thinks that p.

T4 Necessarily, if S is certain that p, then S is convinced that p.

T5 There are at least some cases where it is rational for S to think that p even if S knows that: while p is more likely than ¬p, ¬p is almost as likely as p.

T6 It is possible that S thinks that p, but S is not convinced that p.

T7 It is irrational for S to be convinced that p or certain that p if S knows that: while p is more likely than ¬p, ¬p is almost as likely as p.

T8 It is possible that S is convinced that p, but S is not certain that p.

There are a few final issues to note before moving on. We’ve said little about doubt. Three options arise in the present context: treat doubt (simpliciter) as the contradictory of thinking, or of conviction, or of certainty. Perhaps, when it comes to propositions one has considered, one doubts that p just in case one is not convinced that p. Given the way in which thinking separates from conviction, this leaves room for doubting that p while thinking that p. This can sound odd in the abstract, but it’s less odd in the kinds of cases where thinking and conviction separate from each other, that is, Track Race and Diagnosis. However, we suspect some readers may prefer to treat doubt as the contradictory of thinking or certainty. This raises questions we cannot here consider, and nothing will turn on one’s preferred account of doubt in what follows.Footnote 20

The concept of surety is also among our outright doxastic concepts. But how is surety related to the other outright doxastic states? Goodman and Holguín (Reference Goodman and Holguín2023:640) have it that in English ‘S is sure that p’ means the same as ‘S is certain that p’. Lassiter (2017:123) identifies a similarly tight semantic connection between ‘sure’ and ‘certain’. If correct, then the place of surety just is the place of certainty. We find this connection between certainty and surety intuitive. We have additional questions about surety, but we set them aside,Footnote 21 for the semantic evidence for theorizing about conviction and degrees of conviction is reasonably clear and tractable. Further, by advancing our understanding of the relationships between believing, thinking, conviction, and certainty we will aid those seeking to advance our understanding of surety.

2.3 The Failure of the Lockean Threshold View

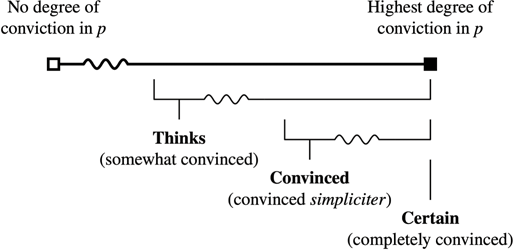

What could explain T1–T8? Foley (Reference Foley1992,Reference Foley1993) has defended a pair of influential ‘Lockean’ claims that can easily be extended to explain T1–T8. Here’s that extension. Start with the widely shared idea that we have degrees of confidence in various claims. Next, identify each kind of outright doxastic state with different threshold-exceeding levels of confidence. For example, on the scale representing our degrees of confidence, let us just specify different thresholds: a thinking threshold that requires some non-trivial degree of confidence, followed by a conviction threshold that requires a higher degree of confidence, and a certainty threshold to be identified with the highest level of confidence. Add to this the further normative thesis that one should proportion one’s confidence level to one’s evidence and you’ll be able to derive T1–T8. Putting all of this into a picture we have Figure 2.

Figure 2 Lockean Threshold View.

First, the hollow box on the left marks the zero-degree point on the scale, while the filled-in box marks the maximum. The exact placement of the thinking and conviction thresholds is not relevant for our purposes. So we use the squiggly segment in each line to indicate our silence on the geometrical distances, and thus to discourage readers from drawing inferences about the proportion of the confidence scale that the thinking and convinced braces include. The structure being defended is an ordinal one, and thus the braces can be moved as readers like. What matters are the relative thresholds: that thinking can involve a weaker degree of confidence than conviction, and both can involve a weaker degree of confidence than certainty.

The Lockean approach is elegant in its simplicity. However, the dominant view these days is that outright doxastic states cannot be reduced to confidence thresholds. The reason for this, as has frequently been pointed out, is that it’s psychologically possible to be very confident that p even in the absence of a belief that p.Footnote 22 These lessons about the separability of belief and high confidence extend to thinking, conviction, and certainty.

To see why many have regarded the separability of belief and high confidence as a datum to be accommodated, consider the following illustrative case:

Lottery. Sam knows that the objective chances (L) that his lottery ticket is a loser are 0.999. Knowing these odds, his confidence that his ticket is a loser is high (but not maximal). But Sam also knows that there would be nothing abnormal should his ticket turn out to be a winner (Smith Reference Smith2016) and that this could easily happen (Williamson Reference Williamson2000). In light of this, Sam is not at all inclined to assert that his ticket is a loser (not even to himself in his head), and Sam is not at all inclined to act on the claim that his ticket is a loser (e.g., by burning it or throwing it away), and Sam is not at all inclined to treat that claim as a premise in deliberation (at most he deliberates on the basis of the high probability of it being a loser). So there is, simply, no standard way in which Sam is inclined to treat L as true. So, Sam does not believe L. Nevertheless, when Sam learns that his ticket is a loser based on a news report, he is utterly unsurprised. And he is utterly unsurprised because he was extremely confident that that possible outcome – his having a losing ticket – would be the actual outcome.

Narratives such as this are intended to draw attention to a psychological possibility: high confidence states and belief states can come apart. Indeed, the case for separating belief and high confidence is provable, conditional on certain ways of characterizing both states. We’ll discuss this further in Section 5.1.

Given that Lottery concerns the relation between belief and confidence levels, what relevance does this case have for theorizing about thinking, conviction, and certainty? Much. Recall that the judgement that Sam fails to believe that his ticket is a loser stems from the observation that Sam has no inclination to assert it, no inclination to act on it, and no inclination to use it in deliberation. But if Sam has no such inclinations, it’s not only intuitive to think that Sam doesn’t believe it, it’s also intuitive to think that Sam doesn’t think that it’s true, is not convinced of it, and is not certain of it. We can add an argument to this intuition. For thinking, conviction, and certainty each entail belief (Section 7.2), and Sam’s absent inclinations (dispositions) in Lottery preclude him from believing L on leading accounts of belief (Section 4.1). If right, then the absence of a belief in L entails the absence of these other outright doxastic states despite the presence of high confidence. If that’s right, then the Lockean Threshold View should be rejected. Fortunately, T1–T8 are not without an explanation. A distinctively Kantian alternative awaits.

3 Degrees of Conviction and the Reduction of Outright States

The previous section examined the place of conviction simpliciter in relation to various outright doxastic states. But conviction also comes in degrees. This is something that seems to have been overlooked as a theoretically useful insight, for on the few occasions where epistemologists talk about ‘degrees of conviction’ they seem to use it synonymously with ‘degree of belief’, ‘degree of confidence’, or ‘credences’.Footnote 23 This is a mistake. The concept of conviction is distinctive and holds the key to an alternative threshold view: a view of our outright attitudes characterized as threshold-exceeding states on an underlying scale that tracks degrees of conviction as opposed to degrees of confidence. The motivation for this is relatively straightforward: once we’ve seen that conviction comes in degrees, it’s very hard to avoid the conclusion that being convinced simpliciter is just a matter of being convinced to a sufficient degree. Given what we learned in the previous section about how conviction simpliciter is logically related to thinking and certainty, a new threshold view presents itself.

3.1 Degrees of Conviction

Why think that there are degrees of conviction? Answer: our way of thinking and talking about conviction presupposes that there are degrees of conviction. We can easily make this point by considering cases. For context, assume that a trial is underway and you’re a jury member assessing the evidence. In response to your growing body of evidence, you might well say any of the following in the course of the trial:

(14) As the evidence increased, I became increasingly convinced that Morrison was guilty.

(14′) ✓Je mehr sich die Hinweise häuften, desto mehr war ich (davon) überzeugt, dass Morrison schuldig ist.

(15) ✓The more the evidence is overturned, the less convinced I become of Morrison’s guilt.

(15′) ✓Je mehr Hinweise widerlegt werden, desto weniger war ich von Morrisons Schuld überzeugt.

(16) ✓I was almost convinced that Morrison was innocent, but then the cross-examination began.

(16′) ✓Ich war fast (davon) überzeugt, dass Morrison unschuldig war, aber dann begann das Kreuzverhör.

(17) ✓I am (slightly) less convinced than I was that Morrison is guilty. However, I remain convinced that he’s guilty.Footnote 24

(17′) ✓Ich bin [ein bisschen] weniger (davon) überzeugt, als ich es war, dass Morrison schuldig ist. Trotzdem bleibe ich (davon) überzeugt, dass er schuldig ist.

(18) ✓I was convinced by the original evidence that Morrison committed the crime, but after his confession and the deep remorse he displayed while confessing, I became completely (/totally/fully) convinced that he committed the crime.

(18′) ✓Ich war aufgrund der ursprünglichen Hinweise (davon) überzeugt, dass Morrison das Verbrechen begangen hat, aber nach seinem Geständnis und der tiefen Reue, die er während seines Geständnisses gezeigt hatte, war ich ganz [/total/vollkommen] (davon) überzeugt, dass er das Verbrechen begangen hat.

The felicity of these statements tells us that ‘convinced’ is semantically gradable and connected to an underlying scale that tracks degrees of conviction.

Notice that (17) and (18) indicate that one can be convinced simpliciter and yet become more or less convinced, and also that one can be convinced simpliciter without being completely convinced. For a comparison consider ‘wet’: something can be wet simpliciter and become more or less wet. A shirt that has been splashed with a very large cup of water will be considered ‘wet’ by most ordinary standards. But if the shirt begins to dry it can become less wet without ceasing to be wet. Alternatively, if the shirt is splashed again with water it will become wetter, and if it’s slowly submerged in water it will become even wetter. Whether a shirt has transitioned from being merely wet to being completely wet will depend on the contextually salient standard of precision.Footnote 25

Notice also that the conviction scale has an uppermost point: being completely convinced. And this uppermost point is naturally identified with certainty. In evidence, consider separating them:

(19) #He’s certain that she arrived, but he’s not completely convinced that she arrived.

(19′) #Er ist (sich) gewiss, dass sie angekommen ist, aber er ist nicht ganz (davon) überzeugt, dass sie angekommen ist.

(20) #He’s completely convinced that she arrived, but he’s not certain that she arrived.

(20′) #Er ist ganz (davon) überzeugt, dass sie angekommen ist, aber er ist (sich) nicht gewiss, dass sie angekommen ist.

Once again, these sound awful.Footnote 26 And they sound awful, we think, because ‘S is certain that p’ refers to the highest degree of conviction,Footnote 27 and vice versa.

Lastly, recall (16). Notice that the expression ‘almost convinced’ implies ‘not convinced’, just as ‘almost dressed’ implies ‘not dressed’ and ‘almost wet’ implies ‘not wet’.Footnote 28 To say that one can be almost convinced despite failing to be convinced (simpliciter) is to say that one’s degree of conviction can fail to be high enough to count as being convinced (simpliciter). A further observation about ‘almost convinced’ is that it implies ‘at least somewhat convinced’. After all, if one were not at least somewhat convinced, one would be either: not at all convinced or close to it (=almost not at all convinced). And if one is either not at all convinced or close to it, one would not be almost convinced.Footnote 29 What would a situation look like where one is almost/somewhat convinced? Recall Diagnosis. There we observed a case where a doctor thinks that a patient has disease A because that is the most likely disease (52%) and also because it is the most typical disease for a patient to have in the given circumstances. We could easily imagine the same doctor saying: ‘I’m at least somewhat convinced that the patient has disease A.’

At this point we are in a position to summarize the observations concerning natural language thresholds on the scale of conviction. They include:

● being completely convinced

● being sufficiently convinced to count as being convinced (simpliciter)

● being at least somewhat convinced

● being not at all convinced

All of these will become relevant in Section 3.2, and we’ll say more about the nature of degrees of conviction in Sections 4 and 5.

3.2 The Kantian Threshold View

We can take each of the aforementioned regions on the degree of conviction scale and connect them to the outright doxastic states discussed in Section 2.2, as indicated in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Kantian Threshold View.

Section 3.1 provided semantic motivations for identifying certainty with being completely convinced, that is, the state picked out by the endpoint on the conviction scale. Similar semantic motivations are available for identifying conviction – that is, the state of being convinced – with having a sufficiently high degree of conviction. After all, it makes no sense to think of oneself or others as being convinced that p, while not being convinced that p to a sufficiently high degree. Moreover, since one can be convinced without being certain (Section 2.2), the degree of conviction required for being convinced must be a degree that falls short of complete conviction.

Where does thinking lie on this scale? Well, we saw that one can think that p without being convinced that p (Section 2.2). So if thinking has a place on the conviction scale, its lower boundary must be below the lower boundary required for being convinced. Further semantic considerations suggest that thinking’s lower-boundary lies with being at least somewhat convinced. In favour of this, consider the questionable felicity of the following conjunctions:

(21) #She thinks that p, but she is not even somewhat convinced that p.

(21′) #Sie denkt, dass p, aber sie ist nicht einmal ansatzweise (davon) überzeugt, dass p.

(22) #She’s somewhat convinced that p, but she doesn’t think that p.

(22′) #Sie ist einigermaßen (davon) überzeugt, dass p, aber sie denkt nicht, dass p.

Try and imagine yourself saying such things. For example: ‘I think she’s on her way, but I’m not even somewhat convinced that she’s on her way’, or ‘I’m somewhat convinced that she’s on her way, but I don’t think she’s on her way’. These sound bizarre. And we cannot easily interpret such statements just in terms of sentence meaning.

The neg-raising behaviour of ‘thinks’ (Section 2.2) may provide additional evidence for connecting thinking and being at least somewhat convinced, for the expression ‘at least somewhat convinced’ seems to neg-raise. For example, uses of ‘he is not even somewhat convinced that she’s home’ tends to suggest that ‘he is somewhat convinced that she’s not home’. Altogether, we have non-trivial evidence for the following explanation of these facts:

T=SC Necessarily, S thinks that p iff S is at least somewhat convinced that p.

Notwendigerweise gilt, S denkt, dass p, genau dann, wenn S wenigstens einigermaßen (davon) überzeugt ist, dass p.Footnote 30

Figure 3, in addition to encoding T=SC, also represents the idea that thinking’s lower boundary should not be too close to the zero-degree endpoint. But remember that the absolute placement of these thresholds is irrelevant to our purposes. They can be moved. What does matter is their relative location: thinking can involve a lower degree of conviction than being convinced, and both can involve a lower degree of conviction than certainty.

Notice how the scalar structure in Figure 3 helps model the facts of Section 2.2:

T1 It is possible that S thinks that p, but S is not certain that p.

In the model, every point within the thinking region that is shy of the endpoint is a point that represents thinking without certainty.

T2 Necessarily, if S is certain that p, then S thinks that p.

In the model, to be at the certainty endpoint just is to be at one point within the thinking region.

T3 Necessarily, if S is convinced that p, then S thinks that p.

In the model, every point in the conviction region is a point within the thinking region.

T4 Necessarily, if S is certain that p, then S is convinced that p.

In the model, the certainty endpoint is always within the conviction region.

T6 It is possible that S thinks that p, but S is not convinced that p.

In the model, there are points within the thinking region that are not within the conviction region.

T8 It is possible that S is convinced that p, but S is not certain that p.

In the model, there are points within the conviction region that fall short of the certainty endpoint.

This is all very tidy. And just as with the Lockean Threshold View, the Kantian Threshold View provides an equally tidy explanation of T5 (=thinking is normatively weaker than conviction) and T7 (=conviction and certainty are not as normatively weak as thinking). We need only avail ourselves of the epistemological principle that we are required to proportion our degree of conviction to the strength of our evidence.Footnote 31

4 The Metaphysics of Belief and Degrees of Conviction

The previous section provided reasons for thinking that there exist degrees of conviction and that we can reduce thinking, conviction, and certainty to degrees of conviction that exceed certain thresholds. The central project of this section is to develop a metaphysical account of degrees of conviction. The account of degrees of conviction to follow stems from the connection between conviction, belief, and a prominent body of research that takes belief to be, at least partially, a dispositional state. We’ll explore a well-motivated framework in which one’s degree of conviction just is, roughly, the degree to which one is disposed to rely on p.

4.1 What Is Belief?

Recent analytic philosophy has had a lot to say about the nature of belief. While there is a good bit of controversy here, there is a widely shared idea that believing that p is at least partially connected to reliance-dispositions: dispositions to rely on p in certain ways when it comes to situations in which one takes p to be relevant.

In evidence, consider the widely endorsed representationalist–functionalist model of belief in the philosophy of mind. As Lyons (Reference Lyons and Lyons2009:71) describes this view: believing that p is ‘a matter of standing in a certain functional relation to a representation, R, which has the content that p,’ where the relevant functional relation involving the representation R is such that ‘R is poised to have [=disposed to have] the causal role definitive of belief: R is used as a premise for inference, for practical syllogisms, and the like (Field Reference Field1978; Fodor Reference Fodor1990)’ (emphasis added). Further connecting belief to reliance-dispositions, Stalnaker (Reference Stalnaker1984:15) says that ‘to believe [p] is to be disposed to act in ways that would tend to satisfy one’s desires, whatever they are, in a world in which p (together with one’s other beliefs) were true’ (emphasis added). Zimmerman (Reference Zimmerman2018:1) writes: ‘To believe something at a given time is to be so disposed that you would use that information to guide those relatively attentive and self-controlled activities you might engage in at that time, whether these activities involve bodily movement or not’ (emphasis added). Ross and Schroeder (Reference Ross and Schroeder2014:267–8) argue that ‘at least part of the functional role of belief is that believing that p defeasibly disposes the believer to treat p as true in her [practical and theoretical] reasoning’ (emphasis added; cf. Frankish Reference Frankish, Huber and Schmidt-Petri2009; Wedgwood Reference Wedgwood2023). Also emphasizing the dispositional character of belief, Weisberg (Reference Weisberg2020:4) writes of two principal characteristics of belief: ‘First, [in believing p] we become disposed to rely on p – to use it as a premise in future reasoning, to assume it in decision-making, and to assert it. … Second, we become resistant to [=disposed to resist] reopening deliberation – we treat the question whether p as settled’ (emphasis added). Schwitzgebel (Reference Schwitzgebel2002) characterizes belief as a dispositional state involving certain behavioural dispositions (dispositions to act and assert), certain cognitive dispositions (dispositions to infer), and certain affective dispositions (the disposition to feel surprise should one’s belief turn out false). There are also knowledge-first characterizations of the dispositional nature of belief: Hyman (Reference Hyman2017:284) writes that ‘we can define the belief that p … as the disposition to act (think, feel) as one would if one knew that p’ (emphasis added; cf. Williamson Reference Williamson2000; McGrath Reference McGrath2021b:175). Leitgeb (Reference Leitgeb2017:70–2) points out that this broadly dispositional vision of belief is not only a credible commitment of contemporary epistemology and philosophy of mind, but it’s also attested to in the history of philosophy, especially in Hume. Section 7 provides evidence that Kant too would have been amenable to a broadly dispositional theory of belief.

We’ll capture the idea that some set of reliance-dispositions are, at least partially, constitutive of belief as follows:

Minimal Nature. At least part of what it is to believe that p is to have a disposition to rely on p in the ways required for belief when p is taken to be relevant.Footnote 32

A few points of clarification. First, the intended idea of relying on p is not simply the idea of using the proposition p. One can use the proposition p in suppositional reasoning even while rejecting p. One can also use the proposition p in at least a derivative sense when one uses the proposition that p is very probable in one’s reasoning. But when one relies on p by, for example, asserting that p, acting on p, and treating p as a premise when aiming to form beliefs about what one ought to do and think, one is relying on p as though it were true. It is unsurprising, then, that we find many characterizing believing that p as: treating /holding /taking /regarding p as true.Footnote 33

Second, the idea of ‘taking p to be relevant’ is what we think the relevant stimulus condition is for triggering a belief’s constitutive dispositions. For an analogy take fragility: the disposition to break when struck. Not every fragile glass breaks. It’s the striking that triggers its disposition to break. In what follows, ‘taking p to be relevant’ is the stimulus condition for belief and it will be left unanalysed. For however it is analysed, it’s very clear that we do take some propositions, and not others, to be relevant when it comes to what to do and to think on particular occasions.Footnote 34

Lastly, the expression ‘the ways required for belief’ is to be filled in with the sorts of ways talked about here in regard to assertion, action, or deliberation. Since different theorists may have different preferences here, we’ve elected to use the neutral ‘ways required for belief’ that you may fill in as you like. But to give us something concrete to work with we will sometimes make reference to the following instance of Minimal Nature:

Minimal Nature + Assertion + Action + Deliberation (MAD): At least part of what it is for an agent S to believe that p is for S to have a disposition to assert that p, or to act on p, or to treat p as a premise in deliberation when S takes the proposition p to be relevant.

MAD is a sane characterization of belief. As noted above, the reliance-dispositions connected to belief are often thought to involve action, assertion, and deliberation. After all, it would be entirely natural to characterize someone as believing that the train station is nearby, if, when taking that claim to be relevant, one had a disposition to assert that claim, to act on it, and to rely on it in deliberation. Furthermore, if someone lacked all three of those dispositions, it would be entirely odd to claim that they believe that the train station is nearby. Many of those cited earlier in this section would agree. But there are subtleties here. For example, clearly one might have a stronger disposition to assert p than to act on p. One might also have a disposition to assert that p while lacking a disposition to deliberate with p. Such dispositional misalignments are probably not uncommon. So we could get more fine-grained than MAD. But MAD is nice to work with. It lets us count someone as a believer just so long as they are disposed to have at least one of the noted responses when taking p to be relevant. Perhaps that’s too low a bar for belief. So bear in mind that MAD is being put forward only as a toy instance of Minimal Nature. Readers unsympathetic to MAD are welcome to substitute their own instance of Minimal Nature in what follows.

4.2 From Belief’s Dispositions to Degrees of Conviction

What is belief’s relation to assent, thinking, conviction, and certainty? Here are four ways of connecting belief to these states:

B=Cert Belief just is certainty.

B=C Belief just is conviction.

B=T Belief just is thinking.

B=A Belief just is assent (Fürwahrhalten, i.e., holding for true).

B=Cert is manifestly implausible. We know none who defend it. Some have explicitly argued for B=T.Footnote 35 In his work on Kant’s epistemology, Chignell (Reference Chignell2007a, Reference Chignell2007b) has argued that contemporary uses of ‘belief’ shouldn’t be taken to refer to assent or opinion, and he comes close to explicitly endorsing B=C.Footnote 36 Crane (Reference Crane and Kriegel2013:164) has advocated B=A and Schwitzgebel (Reference Schwitzgebel2023) suggests that this is the dominant position among contemporary philosophers of mind.Footnote 37 We’ll provide arguments that favour B=A in Section 7.2. But so long as at least one of these views is true and the Kantian Threshold View is correct, we can leverage insights about the dispositional nature of belief to provide us with insights about degrees of conviction.

Here’s the logic of this move. The Kantian Threshold View tells us that thinking, conviction, and certainty are just sufficiently strong degrees of conviction. So any deep metaphysical connection between belief and these threshold states will license some inferences about the nature of degrees of conviction from information we have about the dispositional nature of belief. B=Cert, B=C, and B=T identify belief with some degree of conviction threshold, and thus provide a strong metaphysical basis for theorizing about degrees of conviction in terms of belief’s dispositions. Leveraging B=A requires collateral premises because the Kantian Threshold View says nothing about assent. Recall ‘assenting to p’ expresses the concept of taking p to be the case/holding p as true. Next, notice that thinking, being convinced, and being certain that p seem to constitutively involve the idea of taking it to be the case that p; that is, at least part of what it is to think, be convinced, or be certain that p is to take it to be the case that p. So if both B=A and this partial constitutive claim are true (Section 7.2), then there are metaphysical reasons to move from facts about the dispositional nature of belief/assent to facts about degrees of conviction.

As we aim to unpack degrees of conviction in terms of degreed facts about belief’s dispositions, we need to say something about the structure of dispositions in general. Part of what is involved in having a disposition is for one to respond in a certain way across a given set of possibilities. This is true whether or not one prefers a counterfactual account of dispositions or a version of the modal-proportional approach. The latter approach has become an increasingly prominent approach to the modal structure of dispositions and can be presented thus:

Dispositional Proportionality Principle: Necessarily, x has a disposition to φ when stimulus condition c obtains if and only if x φs in a sufficiently high proportion of the relevant worlds where c obtains.Footnote 38

As has been pointed out by advocates of such accounts, the right-hand side of this principle needn’t be understood as providing a reductive analysis of dispositions nor as providing grounding conditions that partially explain why an object has a given disposition. It is perfectly fine, and surely more intuitive, to treat the left-hand side as more fundamental. What is important for our purposes is that having a disposition tells us something about the structure of modal space.

Notice that when it comes to assessing whether x has a disposition to φ, the Dispositional Proportionality Principle has us focus on the relevant worlds where x exists and its stimulus condition c obtains. So which worlds are relevant? Manley and Wasserman (Reference Manley and Wasserman2008) and other disposition theorists suggest that the relevant worlds should be restricted to worlds where the laws of nature remain the same. They also argue that the relevant worlds should be restricted to worlds where all the intrinsic properties of x remain the same. For example, they write that when it comes to determining an object’s dispositions, ‘we consider what objects would do under various extrinsic conditions in which they are (at the outset) as they actually are intrinsically’ (76). This particular restriction generates a potential disconnect between how at least some advocates of versions of the Dispositional Proportionality Principle would have us understand dispositions and how moral philosophers and epistemologists have thought about the dispositions associated with prominent moral and epistemic virtues (generosity, love, reliability, and so forth). The problem is superficial, but requires attention. We’ll come back to this later in this section.

Let’s first look at the mechanics of the Dispositional Proportionality Principle. Take fragility. A fragile glass is a glass that is disposed to break when struck. What does that involve? According to this principle, it involves the glass breaking in a sufficiently high proportion of worlds where: (i) it is struck, (ii) the laws of nature remain the same, and (iii) all of the glass’s intrinsic properties remain the same. The ‘sufficiently’ qualification is important because breaking in some very small proportion of worlds is not enough to be fragile. The proportion has to be sufficiently high, where ‘sufficiently high’ is determined by the kind of object in question, the kind of disposition in question, and contextually salient standards that can shift the sufficiency threshold.Footnote 39

Among the advantages of modal views of dispositions is that they can be easily leveraged to explain the fact that dispositions come in degrees. As Manley and Wasserman (Reference Manley and Wasserman2007) point out: it is clearly possible for there to be two fragile glasses, g1 and g2, such that g1 is more fragile than g2. That is, g1 has a stronger disposition to break when struck than g2. On modal views, this amounts to saying that the proportion of relevant worlds where g1 is struck and breaks is larger than the proportion of such worlds where g2 is struck and breaks.Footnote 40

Back to belief. Take a normal, mature, human thinker, Sam, in the following possible situation:

PS: At time t, Sam looks into his wallet and sees only ten euros in it.

Does Sam believe the proposition (M) that he has only ten euros in his wallet? To answer this, let us consider situations that seem relevant for whether or not we ascribe to Sam a belief in M:

PS1: Shortly after t, Sam runs into his mother who asks to borrow five euros and Sam thereby comes to take M to be relevant. To what extent does Sam rely on M (e.g., in terms of assertion, action, and deliberation) across (relevant) possible worlds where this situation occurs? For example, does he rely on M across a large, or medium, or small, or very small proportion of these possible situations?

PS2: Shortly after t, Sam goes shopping and is asked to pay for an item costing nine euros and thereby comes to take M to be relevant. To what extent does Sam rely on M across (relevant) possible worlds where this situation occurs?

PS3: Shortly after t, Sam starts thinking about unrelated issues and randomly considers the question whether M is true and thereby comes to take M to be relevant. To what extent does Sam rely on M across (relevant) possible worlds where this situation occurs?

PS4: Shortly after t, someone juggling and wearing a bear costume asks Sam if he has any money and he thereby comes to take M to be relevant. To what extent does Sam rely on M across (relevant) possible worlds where this situation occurs?

PSn: … and so on …

The set of possible situations is vast and involves situations stranger than PS4. But, provided Sam’s apparent evidence for M does not change across PS1–PSn we have the clear sense that if Sam is a typical human with only typical levels of irrationality, he will rely on M in assertion, action, and deliberation across a reasonably large proportion of those possible situations, including PS1–PS4. And if we were convinced otherwise, we would tend to reject the idea that Sam believes M. In this way, believing p is like loving your spouse. Loving your spouse is partially a matter of being disposed to act on behalf of your spouse. But we would never say that you love your spouse if you act on their behalf only when in a very narrow range of circumstances, for example, only when you’ve had two cocktails, and you’re in a good mood, and you’re well rested, and you have absolutely nothing pressing on you mind, and you believe it’s a leap year. The disposition to act on behalf of your spouse that we intuitively associate with loving them involves acting on their behalf across a much broader range of possible circumstances. So too with our ordinary concept of belief.

This point about the range of circumstances associated with belief’s dispositions requires that when it comes to assessing whether an agent believes p at t we do not look only at how they behave in cases where their intrinsic states – for example, their mental states – are exactly as they are at t. For example, in each of PS1–PS4 there are all kinds of mental states of Sam’s that change as he becomes perceptually aware of the many changes in his immediate environment. What this demands is a more inclusive account of the relevant worlds than we find in Manley and Wasserman (Reference Manley and Wasserman2007,Reference Manley and Wasserman2008), whose view involves holding all of an individual’s intrinsic features fixed. That the relevant worlds for many agential dispositions should be more inclusive by allowing for some changes to an agent’s intrinsic features is an entrenched presupposition when thinking about the dispositions associated with our knowledge-producing capacities.Footnote 41

What, then, might the relevant worlds be when it comes to assessing whether someone holds a belief? There is room to disagree over optimal answers to this question. But to get the conversation going let’s note a heuristic for answering this question. First, consider paradigmatic cases where we would ascribe a belief to an agent at a time t. Next, look at the sorts of possible changes to an agent’s intrinsic properties that would or would not make a difference to whether or not we would continue to ascribe the belief to the agent at t. With that as a guiding idea, here is an answer that attracts us:

Belief’s Modal Base of Worlds (BMW). The relevant worlds for assessing whether or not S believes that p (/has a disposition to rely on p in the ways constitutive of belief) at time t in a world w, are the worlds where:

(i) S takes p to be relevant, and

(ii) the laws of nature remain as they are at t in w, and

(iii) S’s internal cognitive processes are as they are at t in w, and

(iv) S’s apparent evidence for p includes the apparent evidence S has for p at t in w, and

(v) S’s apparent evidence for p appears to support p at least as much as it does at t in w.Footnote 42

The need for conditions (i) and (ii) have been noted. Condition (iii) has us exclude worlds where S processes incoming information very differently than she does in w at t. For example, it has us exclude cases where S in w at t processes information like we do, but then later endures psychological conditioning or manipulation that causes her, say, to treat occurrent smells as evidence of facts about ancient history or to treat tautologies as conclusive evidence for arbitrary contingent claims. Intuitively, worlds where one processes information very differently from how one actually does in w at t seem irrelevant to whether or not one believes p in w at t. Perhaps some small differences in one’s cognitive processes should be allowed here. If so, this will be one dimension along which borderline cases can be developed. But borderline cases are inevitable.

Condition (iv) has us hold fixed, for example, an agent’s apparent memories in so far as they seem to have an evidential bearing on whether p. But this condition allows the agent to undergo new experiences and acquire new apparent memories. The motivation for this condition is the obvious fact that a loss of apparent evidence for p can change whether we believe p. So we want to hold one’s apparent evidence fixed when looking at the worlds relevant for assessing whether or not one believes that p at t.

Condition (v) screens off worlds where newly acquired apparent evidence appears to undermine p. For example, suppose at t Sam sees that he’s in a room and comes to believe (R) that he’s in a room. But just after that, at t+, Sam walks out of the room into broad daylight. After walking out of the room he will have no disposition to act, assert, or deliberate on R. But his newly acquired apparent evidence has also shifted as he’s now having a normal perceptual experience of being outside in the sun. Sam now has a very different body of evidence bearing on R: a body of apparent evidence that no longer seems to him to support R. But we would not count Sam’s failure to rely on R upon walking outside against the idea that Sam believed R before walking outside when his apparent evidence continued to appear to support R.

All together, conditions (i)–(v) only ask us to hold fixed a proper subset of an agent’s intrinsic properties across worlds where they exist. We want to emphasize that what follows depends on Minimal Nature (and not MAD) and a version of the Dispositional Proportionality Principle (and not the particular way of identifying the relevant worlds found in BMW). We offer MAD and BMW because they seem reasonably close to correct. Unsympathetic readers are free to refine both MAD and BMW as they see fit.

Now we are in a position to provide an account of degrees of reliance:

Degrees of Reliance. An agent’s degree of reliance on p is determined by the proportion of relevant worlds (e.g., as specified in BMW) in which the agent relies on p in whatever ways are required for belief (e.g., as specified in MAD). The stronger the proportion of relevant worlds in which the agent relies on p, the stronger the degree of reliance.

One advantage of this proposal is that one’s degree of reliance can be represented as a rational number expressed as a fraction n/m, where n is the set of relevant worlds where one relies on p when one takes the proposition p to be relevant, and where m is the total set of relevant worlds where one takes the proposition p to be relevant.Footnote 43 We will not get into the business of assigning numerical values, or measures over infinite sets of relevant worlds. We are here piggybacking off the yeoman work of modal theorists of dispositions who have explicitly analysed dispositions and their degrees in terms of proportionality over infinite sets of worlds. Further, the challenges of fixing numerical values here are no more daunting or more demanding than they are in familiar Bayesian frameworks.

The Kantian Threshold View sketched in Section 3 reduces the outright doxastic states of thinking, conviction, and certainty to degrees of conviction. But that does not itself tell us what degrees of conviction are. So what are degrees of conviction? Provided that ‘belief’ as used in contemporary philosophy of mind and epistemology refers to either assent, or conviction, or thinking, we suggest the following:

Degrees of Conviction (DoC): S’s degree of conviction in p just is the proportion of relevant worlds in which S relies on p in whatever ways are required for belief when S takes the proposition p to be relevant.Footnote 44

That is, degrees of conviction are just degrees of reliance. It is difficult to find reason to reject this without either rejecting (i) the idea that ‘belief’ (as standardly used) refers either to assent, or to thinking, or to conviction, or else rejecting (ii) Minimal Nature, that is, that belief constitutively involves reliance-dispositions.Footnote 45

One thing to bear in mind is that this account of degrees of conviction papers over the psychological complexity noted at the end of Section 4.1. For if belief is associated with multiple ways of relying on p, then we can contrast the proportion of worlds in which one relies on p in one way, w1, with the proportion of worlds in which one relies on p in other ways, w2 or w3. So if belief involves a disposition to rely on p in multiple ways, then there can be a further measurable qualitative difference between agents who, according to DoC, are both convinced of p to the same degree. This point merits exploration that we cannot provide here.

There are further types of degreed doxastic states that we need to discuss to help us see the distinctiveness of DoC. This is the topic of Section 5. Before turning to that there are some final matters to discuss concerning the regions near the extreme ends of the degree of conviction scale. First, recall Figure 3 from Section 3.2. You’ll notice a gap between thinking’s lower boundary and the zero-degree endpoint. You may begin to wonder whether there’s anything worth calling a ‘degree of conviction’ in that gap, especially as one gets close to the zero point. We think so. Again, following Manley and Wasserman (Reference Manley and Wasserman2007:73), let fragility be our model. Consider two non-fragile concrete blocks, that is, both blocks lack a disposition to break when struck. Even though both blocks lack fragility simpliciter, one may yet be ‘more fragile’ than the other in the sense that one breaks in more striking cases than the other. So while we should not think that in that gap in Figure 3 there is a disposition to rely on p simpliciter, there are in that gap degrees of that which makes (or at least marks) such a disposition: possible cases where one takes p to be relevant and then relies on p. The more such cases, the stronger the degree of reliance/conviction. It is only when the proportion is large enough that one will count as having a disposition simpliciter to rely on p when p is taken to be relevant (cf. Vetter Reference Vetter2015:ch.3).

Second, when it comes to degrees of conviction, how large a proportion of worlds is needed to reach a degree of conviction sufficient for being certain (=completely convinced)? It’s a good question, and a hard one. Certainty is, as Unger (Reference Unger1975:ch.2) argued, an absolute term. You are certain, said Unger, just in case you are ‘not at all in doubt’, or as we’ve been putting it ‘completely convinced’. Does that mean that psychological certainty requires that there exist no relevant worlds where you fail to rely on p? Unger would have said ‘Yes’. But Lewis (Reference Lewis1979:353–4) argued that we should not expect a fixed upper bound with many absolute terms; rather, we should expect a flexible upper bound. To see the motivation for a flexible Lewisian account consider the absolute term ‘flat’. To call something ‘flat’ is to say, roughly, that it’s not at all bumpy, bent, or crooked. What do we regard as standard cases of ‘flat’ objects? The desks that populate our libraries and offices, the screens of our computers, and many other ordinary objects. But zoom in close enough to any of these and you’ll find some bumps, bends, and crookedness. So these are not flat objects? ‘No!’ says Lewis. They are flat … according to a somewhat undemanding, contextually salient standard of precision. Many linguists agree with Lewis.Footnote 46 Arguably, then, certainty doesn’t require one to rely on p in every relevant world where they take p to be relevant. One need only do so in enough relevant worlds, where the proportion of worlds required to be ‘enough’ can expand or shrink depending on the contextually salient standard of precision.

Third, the previous point about degrees of precision concerned the upper end of the conviction scale. But what about degrees of precision and the bottom end? Again, we should allow for some flexibility there too as the contextually salient standard of precision might allow one to count as being not at all convinced that p while still relying on p in a sufficiently small proportion of worlds.

Lastly, it should be noted that lacking a disposition to rely on p need have no impact on whether one has a disposition to rely on ¬p. One can lack both dispositions. So being not at all convinced that p does not entail thinking/being at least somewhat convinced that ¬p.

5 The Sui Generity of Degrees of Conviction

Sections 2 and 3 argued that thinking (opinion), conviction, and certainty should be understood in terms of thresholds on a scale that tracks degrees of conviction. Section 4 provided a metaphysical theory of degrees of conviction in terms of degrees of reliance. But how do degrees of conviction relate to other degreed states such as degrees of confidence (credences), degrees of felt conviction, degrees of revisability, and usual characterizations of degrees of belief? This section explains the distinctiveness of degrees of conviction in relation to each of these other states.

5.1 Degrees of Conviction Are Not Degrees of Confidence (Credences)

Degrees of confidence are among our doxastic states. Sometimes we refer to these with the term ‘credences’, though at other times the term ‘credences’ is used to refer to representations of an agent’s mental states in a formal model, for example, in a Bayesian model.Footnote 47 We are not here concerned with formal representations of our mental states, but relations among the states themselves. Additionally, ‘degrees of confidence’ will always refer to non-phenomenal degrees of confidence. That is, we are not concerned with the experience of feeling confident, but with confidence states that are connected to behaviour.

To get a sense of behavioural ways of understanding confidence, consider Greco’s (Reference Greco2015) distinction between asserting that p and hedged assertions of p:

We can distinguish outright, unqualified assertions from assertions that are ‘hedged’ in various ways. Consider the following schematic examples:

1. More likely than not, p

2. Very probably, p

3. With at least 99% probability, p

4. p

Whatever sentence we plug in for p, 1–4 will [when asserted] naturally be heard as expressing increasing levels of confidence.

Assertions of 1–3 are speech acts that put forward ¬p as a possibility at the same time as they put forward p as the dominant possibility. In addition to hedged assertion we have hedged deliberation, that is, deliberation that treats only qualified claims like 1–3 as premises in deciding what to do or to think. Further, we have hedged actions. For example, suppose one’s sole desire is to make as much money as possible by risking up to 100 euros on whether outcome o obtains. Then, bets short of 100 euros (but greater than zero euros) on o may be thought of as ways of performing a hedged action, where the more one will bet on o the more confident one is in o.

These characterizations of hedged activities help us understand the functional role of (non-maximal) confidence. But note: it’s not yet a full theory, much less an analysis, of what degrees of confidence are. We will not provide such a theory in what follows. Rather, we will rely on facts that confidence theorists have widely taken to be obvious about degrees of confidence and then use those facts to distinguish degrees of confidence from degrees of conviction.Footnote 48

Could degrees of conviction be the very same thing as degrees of confidence (credences)? This question brings us back to the following idea:

Conviction–Confidence Identity. Degrees of conviction just are degrees of confidence.

The first problem with this stems from the Lottery case of Section 2.3. There we highlighted how many maintain that there are possible cases in which the following two conditions hold:

High. S has a high, but non-maximal, confidence that p at t.

No. S does not believe that p at t.

Now, if S fails to believe that p, then S must have a low degree of conviction. This follows from the idea that belief is to be identified with either thinking, or conviction, or assent (Section 4.2), and that these states are just a matter of having a sufficiently high degree of conviction (Section 3.2). So from No we get:

Low. S has a low degree of conviction that p at t.

Clearly, we cannot identify degrees of conviction with degrees of confidence if Low and High are jointly possible.

Further problems arise for Conviction–Confidence Identity because we can go lower than Low. For it’s a logical, and surely a metaphysical, possibility that one can have an extreme disposition to rely always and only on the proposition that p is very probable. That is, one’s disposition is so extreme that in no relevant world does one rely on p; rather, in relevant worlds one relies only on the proposition that p is very probable. According to DoC, one would count as being not at all convinced, that is, having no degree of conviction. But even so, one might well have a very high confidence in p if, for example, they have a high degree of conviction that p is very probable. So not only is a high confidence in p compatible with a low degree of conviction in p, high confidence in p is also compatible with no degree of conviction in p.Footnote 49

Section 2.3 noted the widespread view that standard lottery cases are cases where it is rational to be highly confident (L) that one’s ticket is a loser, but it’s not rational to believe it. If it’s not rational to believe L, then it’s not rational to have a degree of conviction in L sufficient for believing L is true. So one’s rational degree of conviction must be reasonably low. So lottery cases are a kind of case where High and Low are rational. A surprising implication of this is that degrees of conviction do not appear fit to be modelled probabilistically, for if one’s rational degrees of conviction are probabilistically coherent, then they do not violate the rule of negation: Pr(¬p) = 1 − Pr(p). But for one’s degrees of conviction to obey this, one’s low degree of conviction in L would require a correspondingly high degree of conviction in ¬L, that is, that one’s ticket is a winner. But it’s absurd to think that in a standard lottery case it is rational to have a high degree of conviction that one’s lottery ticket is a winner. This suggests that even for ideal agents degrees of conviction are not required to be probabilistically coherent.Footnote 50

But what of identifying our outright doxastic states with a maximal degree of confidence? The leading idea here involves identifying outright belief with maximum confidence (‘credence 1’) in a context, where one has maximum confidence in p in a context c just in case one relies on p in assertion, action, or deliberation in c in a way that does not take the possibility of ¬p into account. The role of the contextual parameter, c, is to make sense of the fact that agents often seem to lack maximum confidence in p given the wide range of nearby situations in which they would rely on p in a hedged or qualified way that actually takes the possibility of ¬p into account.

Following Clarke (Reference Clarke2013:10) and Greco (Reference Greco2015), we’ll call this view sensitivism.Footnote 51 Greco (Reference Greco2015) nicely illustrates the mechanics of this approach: