Foreword

I remember exactly how I first began this research. I was moving through a list of book recommendations with asexual characters, screening each one in preliminary research to ensure the asexual character in question was a main character in the narrative. It was this pursuit which led me to a blog post by Karen Healey, author of Guardian of the Dead (Healey Reference Healey2009). In this post, Healey argues for her minor asexual character, Kevin, to be removed from online user-made recommendation lists of asexual characters in literature for young adults (Reference Healey2017). She reasons that Kevin is not the focus of the story, and that the representation his character provides has more or less been a stepping stone toward the more intricate, community-driven representations seen in the Young Adult (YA) fiction published since, largely by authors who self-identify as asexual themselves:

Kevin’s coming out is too much like a confession, my terminology inaccurate and out of date, my explication of his sexuality too glib and misleading. He disappears from the narrative at the halfway point, which works fine for the plot, but is terrible for representation purposes … Kevin’s writer isn’t ace.

Healey’s reasoning is sound. She is aware of Kevin’s shortfalls while simultaneously aware of how important her character was, regardless of them, to a representation-starved asexual audience. She goes on to recommend Every Heart a Doorway (Reference McGuire2016) by Seanan McGuire, a Hugo Award–winning YA fantasy novella starring an asexual main character. I saw no fault in this mature self-reflection, until I reached the comment section:

Reccing Every Heart a Doorway is EXACTLY why [non-asexuals] shouldn’t rec asexual content. Members of the asexual and aromantic communities have been hurt by that book’s representation with matters like linking asexuality with death yet again.

This, to put it lightly, surprised me. The comment makes no mention of the levelheadedness and support I felt Healey had displayed by asking to retract Kevin. All goodwill seemed to have evaporated when she mentioned Every Heart a Doorway, a book which I had personally read and been delighted by. I struggled to see the offense. Like a lot of people, Every Heart a Doorway was the first book I had ever read with an asexual main character. To see my identity spelled out for the first time in fiction was revelatory.

Every Heart a Doorway is a post-portal fantasy starring Nancy, a girl who has returned from her own personal wonderland, a place she refers to as the Halls of the Dead (McGuire 2016). Nancy’s struggles to readjust to life in the mortal world act as a metaphor for the asexual struggle to find personal peace in a compulsorily sexual society. For example, Nancy’s narration describing what it is like to be an asexual person on the romantic spectrum, alienated from sexual traditions and rituals, rings true for many real-life asexuals in the same state: ‘She liked holding hands and trading kisses … It wasn’t until puberty had come along and changed the rules that she’d started pulling away in confusion and disinterest’ (2016:121; emphasis in original). And notably, at the end of the novella, in a moment of empowerment, Nancy gets her happy ending. She returns to the Halls of the Dead, the one place where she has ever felt truly accepted: ‘Like a key that finds its keyhole, Nancy was finally home’ (2016:168–169). This is perhaps the most noteworthy moment in the book, because Nancy has complete control over her future. She has the agency to make her own choice, and she chooses the Halls of the Dead. Suggesting that McGuire somehow equated asexuality and death seemed ridiculous to me, especially since Every Heart a Doorway reframes death as a positive force to the protagonist. Additionally, death more generally is a staple of YA. Roberta Seelinger Trites, a pioneer of this theory, links the commonality of death as a theme in YA to how adolescent readers in the intended age bracket are beginning to understand for the first time the inevitability of death as ‘another biological imperative’ (Reference Seelinger Trites2000:117). In this line of thought, death acts as a rite of passage, typically marking a step toward adulthood. So how could there be something wrong with Nancy’s storyline? What could be upsetting about Nancy’s happy ending – in a novel targeted toward young adults, primed to accept role models through their fiction – where she abandons the world of the living, the world of her family and friends, to become the still, breathless, thanatoid girl she has always longed to be? What was so wrong about an asexual calling a death world ‘home’?

And then I started to understand.

1 Introduction

Asexuality encompasses a range of identities describing people who do not experience sexual attraction, or who do experience this attraction but at low or negligible levels. Like many sexualities, asexuality is a spectrum. While asexual people experience sexual attraction to no one, they may still experience romantic attraction, often desiring romantic relationships which de-emphasise sexual intercourse. Aromantic people, by contrast, are the other way around, experiencing romantic attraction to no one. Likewise, aromantic people may experience sexual attraction in its stead, often desiring sexual relationships along these lines.

This research investigates the overwhelmingly negative trend in asexual character representations, presenting the first academic investigation into depictions of asexual characters as Other in YA fiction. As a concept, the Other dates back to Lacanian discourse of the unconscious Other (Reference Lacan1977) and Foucauldian condemnation of the othering perpetuated by mental institutions and early psychiatry (Reference Foucault1975), with these efforts solely devoted to the making of ‘“abnormal” people normal’ (Nodelman Reference Nodelman1992:35). Put more plainly, the Other is ‘that which is opposite to the person doing the talking or thinking or studying’ (Nodelman Reference Nodelman1992:29): ‘The people more written about than writing, more spoken about than speaking … the culturally invisible or diminished … powerless to take part in the conversations of cultural and other forms of political activity’ (McGillis Reference McGillis1999:xxi). The Other, then, is the voiceless: the invisible. A rich body of scholarship has turned this concept toward reading women as Other, particularly women of colour (Varga-Dobai Reference 92Varga-Dobai2013); reading the migrant as Other; and even reading the child as Other. Perry Nodelman writes on both of these latter examples at once in ‘The Other: Orientalism, Colonialism, and Children’s Literature’ (Reference Nodelman1992), ruminating on how diminutive language around children follows the same imperialist Othering standards as language on people of Asian ancestry (Reference Nodelman1992).

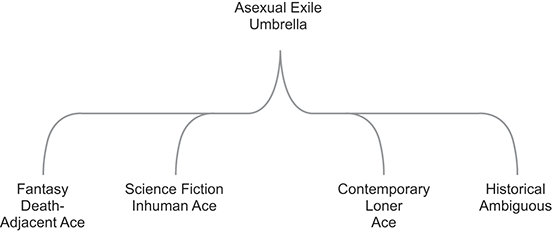

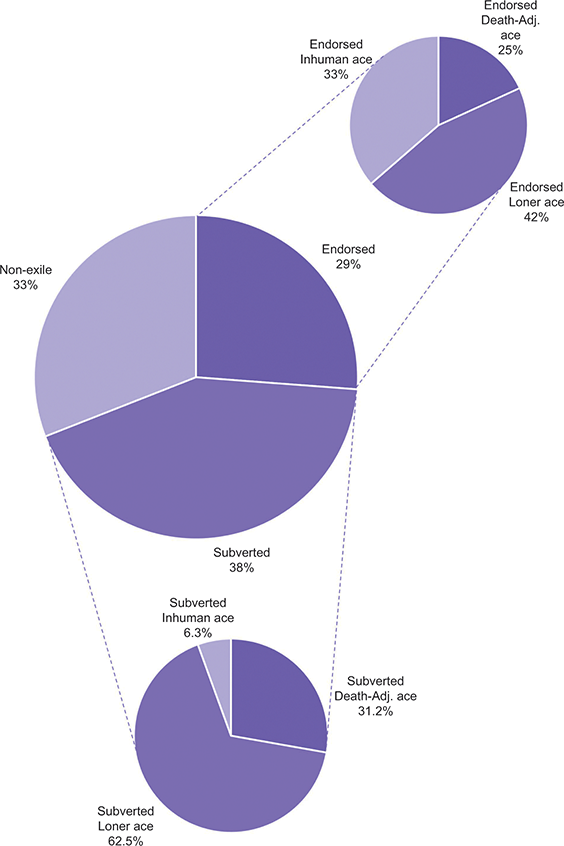

As one means of directing attention toward a theoretical asexual Other in turn, asexual researchers such as Claudie Arseneault (Reference Arseneault2017) and Lynn O’Connacht (Reference O’Connacht2018, Reference O’Connacht2019) have given portrayals of asexuality-as-lifelessness a formal name: the Death-Adjacent Ace trope. It is this same lifelessness that Kennon alludes to in ‘Asexuality and the Potential of Young Adult Literature for Disrupting Allonormativity’ (Reference Kennon2021), noting the trope of asexuals ‘estranged from society and … somehow bound to/with death and being dead’ (Reference Kennon2021:16), though not properly attributing the originators of this critique. Here, I interrogate the frequency, sources, consequences, and potential future of the Death-Adjacent Ace trope, expanding O’Connacht’s existing theory that this is but one branch of a broader representational tree: that of Asexual Exile (Reference O’Connacht2018). In Asexual Exile tropes, asexual characters are separated out of ‘normal’ society. This is achieved not only through depictions of lifelessness but through equivalent depictions of ostracisation, which typically take distinctive forms depending on the genre in which they are located. In the contemporary genre, for example, an asexual character may appear as a friendless social pariah, constituting the Loner Ace trope. In science fiction, the same trend takes the form of the robot or alien asexual character; this exile from personhood is the key feature of the Inhuman Ace trope. My research provides the first ever academic review of Asexual Exile tropes in YA, particularly as they manifest in the fantasy genre in the Death-Adjacent Ace trope. I argue that this is the most severe Asexual Exile trope, demonstrating an exile from life itself.

Through a literary survey of forty-two novels featuring asexual protagonists, I analyse the presence of Asexual Exile tropes across a broad corpus, particularly analysing the negative trends and positive potentialities of these representations. Ultimately, I distinguish the difference between instances of exile that are endorsed by the text compared to those that are subverted, making this assessment through a key query of each case: Does the asexual character enter into an exile, or do they instead exit out of that exile? And as I discuss at length in Chapter 2, are there characters for whom there was never an exile at all? By paying careful attention to each character’s narrative and which side of these questions they fall under, I was able to determine the rates of these trends, appraising the ratio of Asexual Exile subversion narratives compared to endorsement narratives. I have found that overall, 38 per cent of this corpus contain Asexual Exile tropes which are subverted; meanwhile, 29 per cent are left unquestioned, going on to perpetuate Asexual Exile tropes without attempting to reclaim them. On the heels of a deeper examination of these figures, I then provide a reading of the Death-Adjacent Ace trope through the political theory of necropolitics, analysing the dark and unconscious implications of Asexual Exile tropes through their most severe form.

Ultimately, my work here investigates how Asexual Exile tropes operate and what they suggest asexual people are believed to be deserving of under a regime of compulsory sexuality. I argue that these tropes act as a canary in the coal mine: an early portent of an insidious acephobia eager to witness our erasure not only from cultural representations but from society altogether. I go on to explore the ways Asexual Exile can be interrupted, contending that these tropes are fundamentally defeatist. By justifying my interpretation of the potential necropolitical motives behind the popularity of Asexual Exile, interrogating the commonalities of these tropes and theorising potential reclamations of them, it is my hope that this work may provide the beginnings of a path away from the toxic standard of our representation.

1.1 The Community on the Page

There has not been a lot of attention paid to asexuality in seminal works of critique and theorisation about Young Adult literature and its queer inferences. This is largely because these seminal works significantly predate awareness of asexuality entering the mainstream. Patricia Kennon writes on this phenomenon as it pertains to landmark publications by Michael Cart and Christine A. Jenkins, particularly The Heart Has Its Reasons (Reference Cart and Jenkins2006) and its revisions:

The existence or terms of asexual or asexuality are not recognised or included in that influential publication. The same authors’ updated and expanded 2018 version, Representing the Rainbow in Young Adult Literature, does contain a reference to Julie Sondra Decker’s Reference Decker2014 non-fiction text, The Invisible Orientation: An Introduction To Asexuality. However, there is no mention of asexuality in fiction in Representing the Rainbow.

Several years on, we remain in a position where despite Cart and Jenkins using ‘“GLBTQ” as an inclusive short-hand term’ (Reference Cart and Jenkins2006:xv), asexuality has not made the cut. The same is the case in Robert Bittner’s ‘Queering Sex Education: Young Adult Literature with LGBT Content as Complementary Sources of Sex and Sexuality Education’, which overviews the presence of ‘a spectrum of sexualities’ in YA literature, ‘including gay, lesbian, and trans sexual experiences’ (Reference Bittner2012:362). Another example is Logan et al.’s ‘Criteria for the Selection of Young Adult Queer Literature’ (Reference Logan, Lasswell, Hood and Watson2014). Here, the authors’ representation categories extend to gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning, once again omitting asexuality from the conversation. Published in 2014, the excuse no longer exists that asexuality had not yet entered the nomenclature. At the very least, we might say it had not yet become common knowledge and verbiage. The privileging of sexual relationships under the banner of ‘sexual expressiveness’ (Reference Logan, Lasswell, Hood and Watson2014:34) here remains alienating to asexual people regardless:

Adolescent literature that focuses on sexual expressiveness is viewed as relevant, current, and authentic. Sexuality and gender expression is a de facto part of the human explicitness and expressive of those of typical adolescent literature.

It is a difficult space to occupy. While queer critique of YA investigates how young people questioning their identity ‘turn to the “community on the page” that is found in books’ (Cart and Jenkins Reference Cart and Jenkins2006:xvii), the asexual community is nowhere to be found in these conversations. Instead, these conversations highlight again and again the importance of sexual exploration: ‘It is crucial that young people see evidence that a positive future, complete with sexual fulfillment, is possible’ (Bittner Reference Bittner2012:371).

I am often asked, ‘Why Young Adult?’ – a question to which my answer is twofold. For one, YA is a category of literature where asexual characters disproportionately appear – and for another, it is a category of literature where critique has historically left us by the wayside, even though that critique is somewhere we urgently belong. Asexuality may not be mentioned by name, but it feels present thematically. ‘Educators should choose literature’, advise Logan et al., ‘that discourages false images of queer persons and influences healthy perceptions about sexual orientations and gender expression … books that offset stereotyping’ (Reference Logan, Lasswell, Hood and Watson2014:33). This heralds an earlier call made by Cart and Jenkins: ‘we believe that what is stereotypic, wrongheaded, and outdated must be noted and what is accurate, thoughtful, and artful must be applauded’ (Reference Cart and Jenkins2006:xvii). As I will go on to expose, the oversaturation of harmful stereotype in asexual-spectrum YA is critically overdue for this kind of intervention, especially when delaying any longer in bringing these issues to the fore can have fatal consequences. Cart and Jenkins may not name asexuality in their work, but they do name ‘the power of books to help teen readers understand themselves and others, to contribute to the mental health and well-being of GLBTQ youth, and to save lives – and perhaps even to change the world – by informing minds and nourishing spirits’ (Reference Cart and Jenkins2006:xvii). In other words, visibility can have a life-changing impact to isolated youth desperate for an escape. There is power in a name, as Gabrielle Owen advises: ‘The more we feel we can choose our meanings and name ourselves, the more authentic we feel’ (Reference Owen2023:14). However, it is not hyperbole to say that this power can work just as effectively in reverse, condemning readers in the formative years of their identity development to envision themselves through distorted lenses, slowly corroding their self-esteem and will to live. To intervene, we need to say the name. We need to bring asexuality into the conversations which have heretofore omitted us.

1.2 Positionality Statement

There is a lot of ground that this research does not, and cannot, cover. This pertains most significantly to the pervasion of whiteness in asexual literature, both fictional and non-fictional alike (Kennon Reference Kennon2021; Guz et al. Reference Guz, Hecht, Kattari, Gross and Ross2022). This whitewashing is regrettably in line with trends across children’s literature: ‘In 2015, an alarming 73.3 percent of books for young people centered White characters; the nonprofit and grassroots organization We Need Diverse Books was launched in 2014 in an attempt to address this longstanding deficiency’ (Mason Reference Mason2021:21). In the asexual sphere specifically, the ‘privileging of White asexual people’ (Kennon Reference Kennon2021:17) is best interrogated by Guz et al.’s ‘A Scoping Review of Empirical Asexuality Research in Social Science’, an article which provides an ‘inventory of the current empirical literature’ (Reference Guz, Hecht, Kattari, Gross and Ross2022:2135). The authors provide damning findings regarding the sampling of participants in asexual-centric studies:

Descriptive information about the participants included in the literature demonstrates a trend that is presumably cis, overwhelmingly White, and more highly educated … intersectional approach was not commonplace in the included empirical literature.

This is a troubling indicator for asexuality studies which, as a result of this saturation, ‘neglects to interrogate White as a privileged racial category that likely impacts one’s experience identifying as asexual and participating in online asexual communities’ (Guz et al. Reference Guz, Hecht, Kattari, Gross and Ross2022:2142). With this in mind, there is something discomforting about the heavily Westernised list of explicitly asexual protagonists in YA literature, despite the racial and cultural diversity of the characters contained therein. The distant reading this work relies upon is printed almost exclusively between the United States and the United Kingdom, save for one Swedish outlier (Kirchner Reference Kirchner2020). This being the case, I would not be comfortable attempting to apply to this corpus the ‘theoretical and methodological attunement to the ways race structurally interlocks with sex, gender, disability and other visible or invisible identities’ (Reference Guz, Hecht, Kattari, Gross and Ross2022:2141–2142) called for by Guz et al. It is my personal belief that I occupy too privileged a position to properly interrogate ‘allonormativity’s complicity in racist regimes’ (Kennon Reference Kennon2021:18) with any kind of authority.

Though there is a level of intersectionality I cannot claim, I maintain that this work is fundamentally #OwnVoices research. #OwnVoices, a term originally coined by Corinne Duyvis (Reference Duyvis2015), describes works where the under-represented or marginalised characters are written by authors who share in those specific identity categories – as Gabrielle Owen summarises, ‘a call for more diverse characters and diverse authorship in publishing’ (Reference Owen2023:5). In the context of this research, #OwnVoices refers to authors and scholars of asexual characters who self-identify as asexual-spectrum themselves. As is the case in many communities, there has been a push in the asexual community for increased recognition of #OwnVoices works – that is, for works by authors who understand how best to represent asexuality, often incorporating their own lived experience.

Despite these good intentions, #OwnVoices has been a troubled concept since its inception. The condemnation of non-#OwnVoices authors has repeatedly led to ostracisation, gatekeeping, and – at its most serious – the forced disclosure of identity status (Albertalli Reference Albertalli2020; Pulido Reference Pulido2021). ‘The difficulty with the concept of #OwnVoices’, Owen muses, ‘is that it invites questions about who is authorized to write about certain kinds of experiences rather than focusing on the stakes and consequences of the representations themselves’ (Reference Owen2023:7). Treating #OwnVoices authors as immune to fault, able to write representations as they please, compounds these complexities further. I make no secret of my own asexual identity; more specifically, I identify as a homoromantic asexual person on the non-binary gender spectrum. This renders my research project an inherently #OwnVoices endeavour, with my analysis and evaluation being open to the same pitfalls and concerns as any of the novels I critique. That being the case, my research is fundamentally underpinned by the existent field of academic literature into asexuality, particularly sociological research into lived asexual experiences such as accounts of acephobic discrimination and emerging resistance against it. Wherever possible, this research is not a personal outcry tethered to my own instincts and impressions as an #OwnVoices scholar. Rather, it is a project born of what academic literature suggests, and what it would suggest to anyone, regardless of sexuality, should they only care to look. This is not to say that I will erase my asexuality from this discussion by attempting to write clinically about phenomena which fundamentally impact me as part of an asexual collective. Throughout this writing, I use inclusive language to reiterate the innate subjectivity of this research: this is our representation, impacting us. I have not done this to denigrate non-asexual people from this conversation, but rather to remind at all times that this is an asexual conversation, for asexual people, written by an asexual person.

On this note, it is worth dwelling on the fact that Every Heart a Doorway is an #OwnVoices novella itself (McGuire Reference McGuire2017). Nancy is not so easily explained away as an unintentionally problematic attempt at representation by a well-meaning allied author. Instead, that character was written by a biromantic demisexual woman who has presumably experienced firsthand many of the issues facing our community (McGuire Reference McGuire2017). It is not unusual to locate asexual stereotypes in #OwnVoices work in this way, much in the same way that women can write misogynist stereotypes or queer authors can perpetuate homophobia. Again, to reiterate, #OwnVoices authors are by no means somehow rendered immune to representational critique, nor to perpetuating the stereotype so many asexual-spectrum works go on to rally against. Perhaps Owen puts it best: ‘an ethical politics of representation does not rely on #OwnVoices authors’ (Reference Owen2023:1).

This leaves us in an uncomfortable position regarding the impact of Every Heart a Doorway and its representation. Asexual authors and creators sometimes write or favour exiled representations of asexual characters like robots and aliens precisely because they are able to see aspects of themselves in those characters, ‘[looking] toward actual robots in solidarity’ (Brandley and Dehnert Reference 82Brandley and Dehnert2024:1572). After all, it is these desexualised aspects society has labelled us with from the beginning (Sinwell Reference Sinwell, Cerankowski and Milks2014). Perhaps these #OwnVoices exiled representations are a clear response to a ‘boxing-in’ by asexual stereotype categories. In other words, these characters could be an attempt at reclamation by the home team. Nancy might exist in a similar sphere: a girl who removes herself from compulsorily sexual society in order to take back her agency. Whether this self-removal should be taken as a reclamation of agency by an #OwnVoices author, or a surrender toward the negative stereotypes facing our community, is among the thornier questions Asexual Exile tropes ask of us. To address this quandary, I have made a key assessment of whether each instance of Asexual Exile in this corpus goes either endorsed or subverted by the narrative’s end, arguing that these results imply a societal belief that asexuality threatens human futurity and must, therefore, be displaced.

1.3 Acephobia and Death-Adjacent Ace

The Asexual Exile trope I am most interested in is the Death-Adjacent Ace trope, given it is Asexual Exile’s most severe form. To contextualise these death-centric asexuality representations, not to mention the ways in which they have seeded their way into asexuality’s public perception, it is important to first comprehend the conflation of asexuality with lifelessness in a broader cultural understanding.

The Death-Adjacent Ace trope is specific to the asexual community, and is fundamentally distinct from other death-related queer media tropes such as the Bury Your Gays trope (Hulan Reference Hulan2017), wherein queer characters are treated as disposable to a plot. Often perpetuated by straight authors, Bury Your Gays features the killing of queer characters as an implicit punishment for queerness and a bid for ‘shock value’ (Reference Hulan2017:20). Cart and Jenkins describe this same phenomenon when they write of homosexual characters ‘pictures as unfortunates doomed to either a premature death or a life of despair lived at the darkest margins of society. Others are portrayed as sinister predators lurking in the shadows of sinister settings’ (Reference Cart and Jenkins2006:xvi). Bury Your Gays and the Death-Adjacent Ace trope may seem similar because they relate to the discrimination of queer people more broadly. But by comparison, the Death-Adjacent Ace trope, as a form of Asexual Exile, sees asexual characters not necessarily killed off but separated from society altogether. We are reconstituted as lifeless husks who do not belong in ‘normal’, ‘healthy’ society. As far as this trope is concerned, asexuals, much like corpses, have never belonged with the living at all.

The Death-Adjacent Ace trope is born from the asexual death association skewing public perception. As previously explored, the asexual community grapples with associations of inhumanity, coldness, and immaturity, with these perceptions pervading right through to fantasy fiction in the form of the Death-Adjacent Ace trope. This leads me to my main research questions underpinning the present exploration: What does the Death-Adjacent Ace trope signify regarding the state of asexual representation in YA? How do Asexual Exile tropes work to Other asexual characters? What might reclaiming these tropes look like?

Cara MacInnis and Gordon Hodson’s ground-breaking study, ‘Intergroup Bias toward “Group X”’ (Reference MacInnis and Hodson2012), suggests that asexuals are viewed negatively by heterosexual respondents. Their findings indicate that asexuals are also viewed as less capable of experiencing emotion – even, at the most extreme form of this prejudice, perceived as the least ‘human’ of other sexual minority groups (Reference MacInnis and Hodson2012:731). The authors point toward a social obsession with sexual attraction as the key rationale behind this prejudice: ‘Asexuality is operationalized as the absence of sexual attraction, and rationally speaking, should not be linked to strong bias … it is not overly surprising that asexuals are regarded as more mechanistic and lacking some key qualities of human nature’ (Reference MacInnis and Hodson2012:739; emphasis in original). This perception of asexuality as an ‘absence’ or a ‘lack’ of some important, universal feeling is precisely what enables real-world discrimination against asexuals, more commonly referred to as acephobia. With sexuality and desire seen as innately human characteristics in the modern world, asexuals are viewed as defective, broken, and in need of correcting.

Asexual activist Julie Sondra Decker has spoken out on the sexual harassment she has experienced online, where strangers have told her she ‘just [needs] a good raping’ (Mosbergen Reference Mosbergen2013:para.6). She speaks further on surviving an attempted sexual assault by a male friend, who claimed to be able to ‘fix’ her (Reference Mosbergen2013:para.1), telling her ‘I just want to help you’ (Reference Mosbergen2013:para.5). This kind of sexual violence against asexuals is enabled by a media and cultural obsession with sex, one which frames intercourse as an essential human need in a cultural staple known more commonly by the name ‘compulsory sexuality’. This term describes an automatic assumption that all healthy human beings experience sexual attraction as a fact of life. I expand on this theory at length in my first chapter, properly establishing the theoretical context underpinning my work, before turning my attention toward the current research interrogating compulsory sexuality: in particular, how its magnitudinal impact on asexual lives has led to a trickle-down effect on asexual character representations. We can see the product of this trickle-down most clearly in Asexual Exile tropes, which take these cultural perceptions of asexual people as emotionless, inhuman, and cold, and ingrain them into asexual-spectrum YA. The Death-Adjacent Ace trope is the most severe version of this, and though it does not exist in isolation, its instances are rife. To supplement Every Heart a Doorway, another example of the Death-Adjacent Ace trope in action is Clariel by Garth Nix (Reference Nix2014). Here, the aromantic asexual eponymous protagonist loses everyone she loves before losing herself to villainy and undeath. Similarly, in What We Devour by Linsey Miller (Reference Miller2021), the Gods of the world setting force main character Lorena to continue living in order to punish her, denying her the escape into undeath she so craves.

When viewed through the lens of compulsory sexuality, the insidious problem at the core of these novels begins to emerge. At every turn, difference is seen as something in need of repair. Asexual people are Othered in society, as are the characters created to represent us; emerging awareness of this phenomenon served as the catalyst for initial identification of the Death-Adjacent Ace trope to begin with. While Kennon claims ‘the aphobic association of asexual and acespec characters with death’ as ‘particularly deep-rooted’ (Reference Kennon2021:16), she was by no means the first researcher to identify this stereotype. Claudie Arseneault was the first researcher to take the momentum behind compulsory sexuality and use it to interrogate the high rate of asexual characters who ‘belong with the dead’ (Reference Arseneault2017:para.31). She identifies how a pervasive trend in literature associates asexuality with inhumanity, thereby cementing the perception that asexuals are unfeeling and not truly alive, a perception which becomes all the more rampant given compulsory sexuality primes society to view sex as non-negotiable. Lynn O’Connacht expands this theory, interrogating Arseneault’s ideas, even giving the trope its formal name (Reference O’Connacht2018). She proceeds to identify how death and belonging with the dead act in literature as an Asexual Exile trope, ultimately separating the aberrant, Othered asexual character away from ‘normal’ compulsorily sexual society: ‘at their heart, these stories put forth the idea that the aromantic and/or asexual protagonist is something that is not alive’ (Reference O’Connacht2018:para.26).

1.4 The Multiple Genres of Asexual Exile

Exile representations affirm that if we cannot be cured, then we must be contained. The Death-Adjacent Ace trope is just one method through which this occurs and it is paralleled by a cast of asexual characters either written to be alone, or written to be non-human. O’Connacht suggests that, like a chameleon, Asexual Exile mutates in literature to match genre conventions (see Figure 1). In the fantasy genre, this takes the form of the Death-Adjacent Ace trope; in science fiction, asexuals might instead be Othered as a robot, alien, or some other type of the Inhuman Ace trope (Reference O’Connacht2018). In contemporary writing, exile often manifests in the Loner Ace trope, wherein a socially isolated asexual character struggles to connect with their peers: ‘The trope draws these stereotypes to their extremes to explore the ways in which asexuals are not an active part of our societies’ (Reference O’Connacht2018:para.19).

Figure 1 The Asexual Exile trope umbrella

These other forms of Asexual Exile are important when dissecting the overall effect of how these tropes operate. What constitutes all of these variants is a marked separation of the asexual character from a society which refuses to accommodate their difference. This is presented as an ideal solution to asexual difference, usually by asexual characters who, like Nancy, welcome their exile as a happy ending.

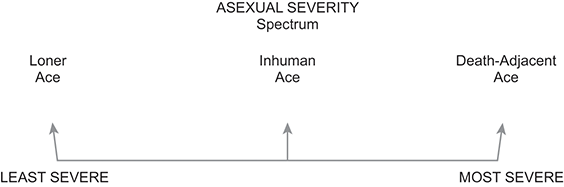

I want to be clear: Asexual Exile is not an exile in the usual sense. Rather than being an expulsion or expatriation from a home country, it is instead an intense social alienation serving to sever all community ties between the asexual character and the world around them – as O’Connacht words it, a ‘social exile as the character removes themselves, voluntarily or not, from … society’ (Reference O’Connacht2018:para.14). The overall impact of Asexual Exile tropes is that they cement and perpetuate a social understanding that asexuals do not belong. The most severe and violent Asexual Exile trope is the Death-Adjacent Ace trope (see Figure 2), which ‘[allows] writers to make this separation from society literal … after all, what is more removed from life than death?’ (O’Connacht Reference O’Connacht2018:para.13). For this reason, my research is most dedicated to understanding, investigating, and reclaiming this Asexual Exile trope in particular. By taking existing research into asexual representations and applying it to the under-critiqued reading category of asexual-spectrum YA, I argue that asexual death-adjacency in this body of literature reaches far beyond the page.

Figure 2 The Asexual Exile severity spectrum

1.5 Chapter Overview: Mapping the Asexual Exile Trope

Through the explorations of my research, I make the argument that Asexual Exile tropes are a portent of an asexual slow death (Berlant Reference Berlant2007), in which an establishmentarian disregard for asexual life and a rank contempt for our frequent childlessness manifests in the persistent messaging that we do not belong, and that our lives do not matter. In Chapter 2, I conduct a literature review to contextualise my research, expanding and deepening the initial points made in this introduction. I define the key term of compulsory sexuality, and establish how it dominates media, culture, and literature as a social framework. From this discussion, I narrow in to summarise the current scholarship into asexual literary representation, particularly critiquing Elizabeth Hanna Hanson’s literary theory of asexual narrative (Reference Hanson, Cerankowski and Milks2014).

Chapter 3 focuses on a literary survey of asexual representation in YA, closely inspired by the distant reading methodology pioneered by Franco Moretti (Reference Moretti2000, Reference Moretti2005). Distant reading aspires to examine trends across a comprehensive corpus of work broadly, rather than by close analysis: ‘fewer elements, hence a sharper sense of their overall interconnection’ (Moretti Reference Moretti2005:1). My investigation delves into how Asexual Exile tropes have impacted asexual representation across YA and what these representations convey to intended young readers. This undertaking necessitates a methodological strategy able to broadly review the field of YA asexual representation as a complete picture, rather than by a close reading of two or three novels in an isolated case study. My literary survey inspects forty-two YA novels with asexual protagonists represented explicitly. I analyse how they engage with Asexual Exile, utilising a selection of key texts to achieve a deeper analysis. To this end, I especially scrutinise the messages communicated to the audience about the place of asexuals in society, determining whether each instance of these Asexual Exile tropes is either subverted or left unquestioned.

With the Death-Adjacent Ace trope being the most severe Asexual Exile trope – not to mention the form with the clearest interplay with existing social conceptions of asexuals as less alive (MacInnis and Hodson Reference MacInnis and Hodson2012) – I examine this specific sub-trope in my third chapter, analysing its critical complexities through the lens of Achille Mbembe’s necropolitics (Reference Mbembe2003) and Lee Edelman’s death drive (Reference Edelman2004). Necropolitics is a political theory identifying how people who hold social and political power are able to dictate which groups are worthy of living and which groups must die (Mbembe Reference Mbembe2003). As depictions of asexual characters as lifeless outliers now saturate literary representations aimed at adolescent readers, it is more crucial than ever to interrogate these stereotypes condemning asexuals to a mass grave. I interrogate the excuses used to justify widespread discrimination against asexuals – for example, a biopolitical connection equating sex-aversion with voluntary childlessness. I argue that asexual sex-aversion is seen primarily as a rejection of human reproductive function and that alienation from this ‘compulsory reproduction’ (Franke Reference Franke2001) thus encompasses asexuals firmly within Edelman’s understanding of future-negating queers (Reference Edelman2004:75). I examine whether this constitutes part of why asexual representations are so often connoted with death – because we are connoted with death – because the fundamentally queer choice many of us make not to procreate is viewed as a gun to the head of human longevity.

Asexuals deserve better than a legacy of discrimination and disrespect. We deserve more than to have drummed into us and our non-asexual peers at every turn that we do not belong – can never belong – and, therefore, should consign ourselves to the very margins of society in the form of isolation, non-humanity, and undeath. We deserve stories and representation custom-made to intervene into our ongoing social exile, one happening not just in our fiction but, as I go on to demonstrate, in our lived realities, too.

2 Compulsory Sexuality and the Tensions We Inherit

Before we can understand exile, we must understand the aspects of society asexuals are being exiled from. In the introduction, I gestured toward the biases against asexuals, the violence of acephobia, and how these attitudes are enabled by the primacy of sexual attraction in everyday life. This primacy has gone by different terms, such as ‘a society of sex’ (Foucault Reference 84Foucault1976), ‘sexusociety’ (Przybylo Reference Przybylo2011), and ‘the sexual assumption’ (Carrigan Reference Carrigan2011). However, it is most commonly termed ‘compulsory sexuality’ (Emens Reference Emens2014; Gupta Reference Gupta2015, Reference Gupta2017; Vance Reference Vance2018). It is this term that I will go on to use throughout my research.

Compulsory sexuality theory fundamentally informs asexual media critique. This is because compulsory sexuality wields a constant oppressive influence over asexual lives, and thus, over the asexual lives represented in stories about us. Whether an asexual storyline features a surrender to the negative impacts of sex-obsessed culture or a fierce upheaval of these impacts by asexual characters who refuse to conform, these asexual storylines are all foregrounded by the compulsory sexuality asexuals have no choice but to navigate in the real world. This chapter reviews the existent literature into compulsory sexuality, narrowing in on asexual representation in fiction and the commonality of stillness among these representations. Finally, I dispute Hanson’s reading of stillness in emergent asexual literary theory (Reference Hanson, Cerankowski and Milks2014), condemning its harmful impact and latent acephobic connotations.

2.1 A Brief History of Compulsory Sexuality

Compulsory sexuality, a relatively emergent way of understanding societal preoccupation with sexual intercourse, draws from the pre-existing theory of compulsory heterosexuality first identified and examined by Adrienne Rich. Rich (Reference Rich1980) argues that the default assumption of women as heterosexual beings, and the simultaneous assumption that women who are not heterosexual are abnormal, operates as a form of social control: ‘compulsory heterosexuality, through which lesbian experience is perceived on a scale ranging from deviant to abhorrent, or simply rendered invisible’ (Reference Rich1980:632). Similarly, compulsory sexuality assumes that the default human being is a sexual being, an underpinning which not only disadvantages asexual people but disadvantages everyone. Take, for example, a young person not comfortable experimenting sexually but forcing themselves to do so because that is what all their friends are doing. Similarly, we might imagine someone hesitant to leave an abusive relationship because they have been conditioned to believe that any love, no matter how cruel, is better than no love at all.

Compulsory sexuality prioritises sex, thereby creating expectations around sex as an essential aspect of a romantic relationship and pathologising any absence thereof. This falsely renders sex as an essential part of individual life, a foundational building block of human experience, and people who do not partake of it are thereby seen as wrong, deficient, or even pitiful. This is objectionable for a myriad of reasons, not least because it places sexual attraction on a pedestal, gearing young people toward unhealthy expectations around romantic relationships. This societal refusal to acknowledge or respect romantic relationships not predicated upon sex gestures damningly toward the collapse of sex and love into the same ‘inextricable’ force (McAlister Reference McAlister2020:12). If no-strings-attached sex can be commonplace, then why not no-strings-attached romance?

Studies into compulsory sexuality have been adapted in interesting sociological ways. For example, Elizabeth Emens (Reference Emens2014) tracks the ways through which compulsory sexuality pervades the American legal system, privileging sex and disadvantaging asexuals. Ela Przybylo (Reference Przybylo2011), by contrast, considers compulsory sexuality from a radical perspective, viewing asexuality largely in terms of its disruptive potential. She argues that discourse surrounding asexuality represents a fundamental attack on dominant social understandings of sexual control, likening the asexual struggle against compulsory sexuality to the struggles of feminists against patriarchy (Reference Przybylo2011:446). Przybylo goes on to dissect the repeating patterns of a society where sexuality is omnipresent and used to subjugate: ‘The impetus to pathologize those who are not sexual enough, or who do not repeat sexuality faithfully to ‘the norm’, is indicative of which repetitions are favoured by sexusociety … [this] embodies sexusociety’s interest in maintaining a society that repeats along sexual lines’ (Reference Przybylo2011:449). These assertions, while political and labelled ‘unempirical’ elsewhere (Dawson et al. Reference Dawson, Scott and McDonnell2018), have been validated by subsequent research. For instance, Kristina Gupta (Reference Gupta2017) corroborates Przybylo in her landmark interrogation of compulsory sexuality’s impact on asexual people. She identifies and dissects the four main ways through which asexual-identified individuals from her study saw themselves as disadvantaged by compulsory sexuality: (1) pathologisation by medical professionals, usually by falsely identifying asexuality as a symptom of a health disorder, (2) isolation and invisibility due to a lack of representation in the media, contributing to public ignorance about asexuality as a valid sexual orientation, (3) unwanted sex and relationship conflict stemming from misunderstandings around attraction, particularly the false belief that sex is an essential component of a romantic partnership, and (4) a denial of epistemic authority – the removal of asexual agency by non-asexuals who cast doubt on individual asexual knowledge and self-understanding. This final means of disadvantage is particularly insidious. The asexuals interviewed in Gupta’s study reported that they were told ‘that they could not know that they were asexual – they were told that they could be late bloomers, they had not met the right person yet, or they were repressing their sexual desires’ (Reference Gupta2017:1000). This mirrors Gupta’s first point of disadvantage, medical pathologisation, albeit with one key difference. Here, we can infer a handing down of this asexual minimisation from medical professionals to everyday peers, whose scepticism in the fact of asexual self-actualisation is given with as much well-meaning cruelty as that by any doctor; the misconceptions of the health system are now reaching into community-level stereotypes. Taken together, we can see that compulsory sexuality ingrains a truth into us, until we know it like we know breathing. If you are not having sex, then you are not truly alive.

Gupta’s study also uncovers ample evidence of violent discrimination such as sexual assault (Reference Gupta2017:1010), with several more respondents describing engaging in ‘consensual but unwanted sex’ due to expectations by society or by a partner (Reference Gupta2017:998). These represent some of the more traumatic manifestations of acephobia in modern life, the impacts of compulsory sexuality having rendered asexuality so alien and unnatural that sexual assault, unthinkable at any other time, is understood by some to be justified (Decker Reference Decker2014; Gupta Reference Gupta2015). If asexuality is a defect, then sexual intercourse, whether you desire it or not, must be the correction. Consensual unwanted sex is a world away from the more serious response of corrective rape. However, it remains violent in a quieter way. Both can only occur when asexual voices are ignored – more specifically, when non-asexuals believe that asexuality is something which can be ‘fixed’. Responses of doubt to asexual self-identifications are made with the same justification. Tiina Vares documents accounts of social isolation as a result of asexual media invisibility, particularly the myriad reactions to asexual self-identification they result in: ‘it doesn’t exist; it’s just a phase; you’ll grow out of it; and you just haven’t found the right person yet’ (Reference Vares2018:526).Footnote 1 Here, we can see some of the ways asexual voices are silenced and spoken over, with the right to self-identify and diagnose one’s attractions or absence thereof fundamentally undermined. Like branches of the same tree, these discriminations lead back to the same violence, one which is always rooted in taking away asexual agency. Overall, from the discrimination and biases against asexuals on a cultural stance to the attitudes evidenced from both inside and outside of the LGBT community (Gupta Reference Gupta2017:1000), recent research has taken the implications of ‘Intergroup bias toward “Group X”’ (2012) and further verified them. This justifies these implications as an area deserving of closer cross-disciplinary attention, including in literary studies, to which I now turn.

2.2 Asexual Representation in Fiction

Challenging compulsory sexuality can only be done by identifying its controlling impacts in culture and media. One way of achieving this is by adapting compulsory sexuality critique into new areas of research, such as what Emens has done in legal studies (Reference Emens2014). Inspired by this, I examine compulsory sexuality in fiction aimed at young readers, given that asexual characters commonly critique compulsory sexuality on-page. These characters often rally against these social pressures, struggling to carve out a place for themselves in a compulsorily sexual society which typically serves as a one-to-one import of our own.

It is logical to turn our attention toward YA, where many of these asexual representations are located (O’Connor Reference O’Connor2019). However, this is not to say that there is an overwhelm of asexual representations from which to choose. Indeed, the low rate of asexual representation in the mainstream has a well-documented isolating effect on real-world asexuals. Several of Gupta’s respondents spoke about feeling isolated due to a lack of asexual visibility, as well as feeling directionless as a result of no asexual role models to compare themselves to: ‘it’s hard to figure stuff out just because there’s no examples’ (Reference Gupta2017:998). This link has been corroborated by subsequent research, such as an exploratory study by Erin Hampson in which ‘all participants alluded to the invisibility of their asexuality identity’ (Reference Hampson2020:32), equally noting the burdensome nature of having to ‘explain asexuality and justify their identity due to the lack of visibility and understanding of others’ (Reference Hampson2020:33). It comes as no surprise that scholarly interrogations of the few existing asexual representations in media are sparse. What interrogations do exist unanimously scrutinise the harmful messages these representations often convey (Cerankowski Reference Cerankowski, Cerankowski and Milks2014; Przybylo Reference Przybylo, Fischer and Seidman2016; Osterwald Reference Osterwald2017). As the regime of compulsory sexuality in white Western cultures dictates that a life without sex is unacceptable, this cultural messaging seeps through into representations of asexuality. Perhaps the best interrogation of this is Sarah Sinwell’s (Reference Sinwell, Cerankowski and Milks2014) critique of asexuals depicted as desexualised social aliens onscreen, examining the eponymous, asexual-leaning character Dexter – notably aligned with death, as a killer of other killers (Reference Sinwell, Cerankowski and Milks2014:169) – to suggest that compulsory sexuality’s Othering of asexuals reaches not just real-world asexuals but even our imaginary counterparts on television.

However, there is little corresponding study into fiction, with media and television asexualsFootnote 2 analysed far more often than their literary counterparts. This seems disproportionate, given that the number of asexual characters in literature vastly outweighs the amount onscreen. My previous research has examined how these literary asexual characters are disproportionately found in the YA fantasy genre; of a list of YA titles with asexual main characters compiled by Quiet YA (Reference Quiet2016), 43 per cent are primarily shelved under ‘Fantasy’ by Goodreads users (O’Connor Reference O’Connor2019). Nonetheless, there is a second notable coterie of literary asexual representations in contemporary YA – 26 per cent of the same Quiet YA list – many of which act as fictional mirrors of real-life asexual coming-of-age stories (O’Connor Reference O’Connor2019). For instance, Alex Henderson (Reference Henderson2019), a self-identified #OwnVoices asexual researcher, examines the coming-of-age narrative parallels in Tash Hearts Tolstoy (Ormsbee Reference Ormsbee2017) and Let’s Talk about Love (Kann Reference Kann2018), two YA novels with asexual main characters. They note how their tropes and structures help ‘to normalise asexuality as simply another way to experience adolescence’ (Reference Henderson2019:2). Likewise, Brittney Miles, another #OwnVoices asexual researcher, examines Let’s Talk about Love and its value for Black asexuals seeking agency in their representations (Miles Reference Miles2019). These #OwnVoices contributions to the field endorse positive representations, encouraging additional work to come forward in the same vein.

While it is affirming to see asexual YA critiqued by #OwnVoices research, it is less encouraging to see the harmful commonalities these representations contain more generally. I have already established that asexual representations trend toward social exile, with characters often misrepresented as callous or unfeeling as a justification for their aggressive alienation from the compulsorily sexual ‘human’ sphere set on rejecting them. Regardless of the content of these representations, their overall frequency remains worryingly low as well. O’Connacht’s overview of the current state of asexual representation provides some disheartening figures, including that the approximate overall amount of asexual representation in American science fiction/fantasy fiction is just 0.00007 per cent, and that this figure only rises to approximately 0.43 per cent when looking at speculative fiction specifically (Reference Miles2019:para.29). It is worth noting that the methodology behind these statistics is tenuous. O’Connacht arrives at this figure by a potentially inaccurate averaging of available data, admitting that this is at best an estimation, casting some doubt over her further analysis. She indicates that the Death-Adjacent Ace trope may not actually be overwhelmingly pervasive – instead, it may simply be present in many of the most well-known fantasy titles with asexual characters, causing it to be disproportionately visible in the mainstream (Reference Miles2019). Despite these methodological issues, what O’Connacht’s figures indicate is a dearth of accurate data into the frequency and visibility of the Death-Adjacent Ace trope and its sibling tropes beneath the banner of Asexual Exile. Without this evidence, it is difficult to gauge at present how endemic these tropes might be. In later chapters, my research provides the first formal academic investigation into the rates of Asexual Exile in YA. By conducting a literary survey examining asexual characters in this reading category, particularly their traits, storylines, and exile status, I go on to make clear assertions about the frequency of Asexual Exile tropes in YA fiction, especially the Death-Adjacent Ace trope. I also assess the subversive representations to be found in this same corpus and how these healthier alternatives to exile can spearhead change in the ways asexuals are perceived, and the ways we come to perceive ourselves. Cart and Jenkins once wrote of ‘novels [which] told readers how gay/lesbian people were viewed by others, but did not tell readers how gay/lesbian people viewed themselves’, pondering whether ‘this literature is finally beginning to be written’ (Reference Cart and Jenkins2006:171–172). It was being written, and it continues to be written. And now, introspective asexual literature lines the shelves alongside it.

2.3 Stillness and the Asexual Narrative

The intersection of asexuality and its inferences in literary studies is not entirely unbroken ground. To foreground my own research into this area, I will now analyse a piece of previous scholarship which ultimately did more harm than good by reinforcing the lifeless asexual stereotype: ‘Toward an asexual narrative structure’ by Elizabeth Hanna Hanson (Reference Hanson, Cerankowski and Milks2014). Hanson supplies the first – and to date, the only – academic theorisation of an asexual narrative structure, pondering what an asexual narrative might resemble. She argues that an asexual narrative is a storyline which is stagnant, lifeless, and ‘stands still’ (Reference Hanson, Cerankowski and Milks2014:349), reliant upon a ‘tendency toward stasis’ (Reference Hanson, Cerankowski and Milks2014:347), and ‘more or less a story in which nothing happens’ (Reference Hanson, Cerankowski and Milks2014:348). The chapter troubles me on a personal level, as it has done for many other asexual and allied researchers. Nathan Snaza surmises Hanson’s reading of asexuality as a ‘threat to narrative structure’ (Reference Snaza2020:126; emphasis in original), and KJ Cerankowski disputes Hanson’s claim that ‘asexual narrative is absent of desire’ (Reference Cerankowski, Rhodes and Alexander2022:237), arguing that these stories are full of desires should the reader only look beyond compulsory sexual expectations. Several of Hanson’s passages are troublingly reminiscent of acephobic gatekeeping:Footnote 3

What asexuals hide is the fact that they have nothing to hide; their sexual secret is that they have no sexual secret. The asexual closet, then, is empty, is not even a closet – although to position asexuality as a sexual secret, as the content of a secret, as a depth concealed by a surface, is to give the asexual nothing the shape of a something.

Hanson’s claims continue in the tired tradition of taking the identification of sex as a human motivator (Foucault Reference 84Foucault1976), then taking this theory a step further by framing sex as a storytelling motivator, too: ‘Sex … has become the Big Story’ (Plummer Reference Plummer1995:4). But by reversing this argument, bypassing the idea of sex as narrative catalyst and instead implicating asexuality as narrative stagnation, Hanson entwines asexuality and lifelessness in the only existing experimentation with asexual literary theory. She makes a slight clarification to justify this language – ‘By “nothing,” I don’t mean literally nothing … What I mean is something nearer to “nothing of consequence”’ (Reference Hanson, Cerankowski and Milks2014:357; emphasis in original). This is hardly reassuring. Hanson is not discussing asexual representation, or even asexuality itself. Instead, she is taking what she sees as the idea of asexuality – the idea of asexuality as a lack of something essential, an asexuality rendered through the lens of compulsory sexuality – and transposing this absence into the core of a theoretical narrative structure: ‘Asexually structured narrative [opposes] forward movement, closure, and intellectual mastery and embodies stasis, the suspension of desire, the non-event, and indifference to the meaningful narrative end’ (Reference Hanson, Cerankowski and Milks2014:367).

Hanson’s chapter acts as a further indicator of how pervasive the association between asexuality and lifelessness continues to become. Her work here – again, the foundational work exploring implications of asexual literary theory – gives us a clear picture of how asexuality is often understood: static, still, and anticlimactic. In turn, her endorsement of asexual narratives as ‘stories of stasis’ only makes the asexual-death box all the harder to break out of (Arseneault Reference Arseneault2017:para.10). It is these same assumptions which underpin MacInnis and Hodson’s findings explored previously, being that asexuals are publicly understood as emotionless and less human than other people (Reference MacInnis and Hodson2012). This leaves us with clear questions. If asexually structured narrative is most easily seen as a non-event, then what does this mean for how asexuality is understood overall in fiction? What follow-on effect do these biases have for young readers? How does this impact the representations we consume, and the representations we create? In order to clarify the problem before us and the mechanics of how it operates, the next chapter begins the work of answering these questions by analysing the Asexual Exile tropes previously described. I overview the key features of each one and their saturation rates in this corpus, determining which percentage of Asexual Exile tropes are endorsement and subversion narratives, respectively.

Constant asexual dehumanisation justifies ongoing acephobic discrimination, contaminating our public opinion and the discourse it generates. Not only do I present academic statistics into the Asexual Exile phenomenon but I scrutinise how it is being perpetuated and how these perpetuations can be interrupted – how they must be interrupted, even, in order to break this repeating pattern between representations of asexual exile and the lived experience of asexual exile happening in real time as a result. Before anything else, we are known as Other. It is in all of our stereotypes and all of our pain. And because this Othering is all people know about us, it overbearingly appears in stories about us, which primes readers to accept these stories as truths and go on to perpetuate them in turn. What emerges is an ouroboros of exile, reigning from reality to representation and back again, a snake forever eating its own tail. The only way to make it stop is to cut off the head of the snake.

3 Death, Exile, and Possibilities in Asexual YA Fiction

I begin this chapter by detailing the methodology behind my literary survey, summarising the inclusion and exclusion criteria informing my selections. With this process established, I go on to outline the typical qualities of each exile variant, presenting statistics on whether they are more commonly endorsed (wherein the asexual character is socially exiled without question) or more commonly subverted (where the exile trope is written through a self-aware lens, instead of having the asexual character avert or return from their social exile). This discussion leads me to present the field of asexual representation in YA fiction as one which is by no means unanimously hostile nor unanimously encouraging. Instead, it is complicated, nuanced and rife with the possibility for constructive change.

3.1 Methodology

As outlined in the introduction, the literary survey I conducted follows in the footsteps of Moretti’s distant reading methodology (Reference Moretti2000, Reference Moretti2005), with my survey corpus containing forty-two YA novels. In each one, asexual protagonists are represented explicitly on-page. All of these novels were published between 2013 (with the appearance of the first explicitly asexual main character in YA fiction) and 2021, with 2018 being the most prolific window for asexual main characters in YA. Twelve of the novels under examination were published in this single year (29 per cent), with nine following in 2019 (21 per cent), and a further seven in 2020 (17 per cent). Combined, this three-year period accounts for 68 per cent of the novels in my corpus. This peak period of asexual-spectrum YA parallels existing research by Ellen Carter (Reference Carter2020). Carter identifies 2016 as the peak publishing window for asexual-spectrum romance novels, with the consequent petering-off by publishers in following years a likely indicator of unsatisfactory market performance (Reference Carter2020:5). It is worth noting that my study inspects multiple genres of asexual-spectrum YA, whereas Carter’s research examines asexual-spectrum romance novels encompassing adult markets and YA. For this reason, our findings are not completely in lock step. My research indicates 2018 as the major publishing period for asexual-spectrum YA, some two years after asexual-spectrum romance peaked previously (Carter Reference Carter2020). Taking our findings in tandem, this suggests a longer range of the asexual ‘boom period’ in YA compared to in romance. This could indicate that asexual characters are better received by younger audiences. It could also suggest a similar asexual ‘experiment’ as publishers tested in the romance genre two years beforehand, but with a longer petering-off period to match a longer period of experimentation.

The scarcity of asexual representation in fiction, much like the scarcity of ‘GLBTQ content’ in decades previous (Cart and Jenkins Reference Cart and Jenkins2006:169), has resulted in a marked difficulty locating these representations unguided. For this reason, there is an online community dedicated to documenting and sharing these representations when they occur. The two most notable sources I consulted when compiling my corpus shortlist were the AroAce Database created by Claudie Arseneault (2021–) and the ‘Books with Asexual Main Characters’ master-list compiled and maintained by Quiet YA (Reference Quiet2016). I refined this shortlist based on my own personal interpretation of each novel as I read them, excluding from the corpus the instances where I deemed the asexual character’s role in the story either too minimal to be considered a main character, or where the representation itself was minor enough that it would likely go overlooked by potential readers.

While I am confident that this corpus is a reasonably comprehensive sample of the existent state of asexual representation in mainstream YA, I by no means make the claim that this sample is all-encompassing. One inclusion criterion I employed was that the novels needed to be traditionally published rather than self-published or solely available online. My rationale for this is that, when analysing the representational lessons young readers might derive from this literature, it seemed sensible to limit this analysis to the representations young readers could easily encounter. This ensures the integrity of this research as a study into asexual representation specifically in the traditionally published YA fiction scene. The result of this stipulation is that some of the publishers in my corpus are more recognisable than others, ranging from imprints of ‘Big Six’ publishing houses such as HarperCollins and Simon & Schuster all the way to boutique small presses such as Snowy Wings Publishing and Gurt Dog Press.

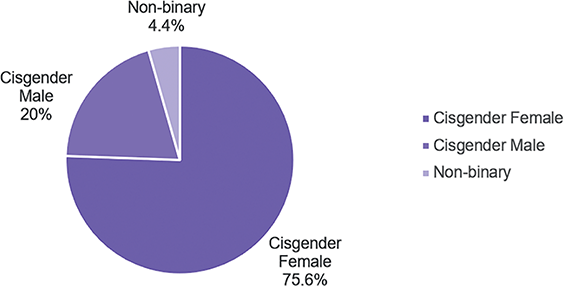

For each of the forty-two novels under study, I tabled objective data such as title, author, publisher, year of publication, genre, tense, perspective, and focalisation of the work. In addition, I assessed more subjective elements of the works such as the gender identity and sex-aversion status of the asexual characters, most prominently including: the degree of explicitness in the asexual representation, the romantic orientation of the asexual characters under study, whether the work features an Asexual Exile trope and which one if so, and finally, whether that trope is endorsed or subverted by the text. The resultant data from this literary survey gives sorely needed statistical evidence on Asexual Exile tropes. Drawn from a broad sample, my conclusions from this data are strongly suggestive of exile rates across asexual-spectrum YA, reasonably answering the question of just how endemic Asexual Exile tropes truly are in this literature. I made my determinations of whether a work endorses or subverts these tropes by assessing each instance through close reading and applying my own deductive reasoning. I identified which novels included these tropes by referring back to O’Connacht’s explications of how each exile variant appears and functions (Reference O’Connacht2018), then assessing each novel against this framework. As for the nature of these representations, the distant reading method allowed me to definitively conclude the ratios of endorsed-versus-subverted representations within the field, supported by clear and demonstrable evidence, a rigour which has been heretofore absent from discourse surrounding this subject. Admittedly, there is an inherently personal nature to the issue at hand. I cannot objectively examine a literary trend which serves to equate asexuality with unbelonging, most severely unbelonging as lifelessness. It is worth noting that I have drawn from my own experience and knowledge as an #OwnVoices asexual researcher and academic in order to make my appraisals regarding the corpus at hand, meaning my conclusions are not altogether free from bias. However, I would argue that, given the complex nature of the Death-Adjacent Ace trope and the equivalent tropes it exists alongside, a subjective critique of this phenomenon is the only accountable path forward. These dangerous tropes are an inherently #OwnVoices issue; they implicate us, they were contributed to by us, and it is us alone who can intervene into them and stop them in their tracks.

3.1.1 Explicit Representation

My research analyses and diagnoses the representational pitfalls of asexual representation in YA fiction in order to make the argument that Asexual Exile tropes, most severely among them the Death-Adjacent Ace trope, contribute to an asexual slow death (Berlant Reference Berlant2007). Therefore, it seems prudent to ensure that the asexual characters under consideration in my corpus must be ‘explicitly outed within the text by authors’ (Bittner Reference Bittner2016:202) – that is, that their asexuality is textual rather than subtextual, and not something a reasonable reader could misunderstand or fail to recognise. For this reason, I have ruled out from my literary survey any novels where characters were only confirmed as asexual paratextually by the author after publication, such as Afterworlds by Scott Westerfeld (Reference Westerfeld2014) and No More Heroes by Michelle Kan (Reference Kan2015).

Of the forty-two novels in my literary survey, thirty (71 per cent) represent asexuality explicitly by using the word ‘asexual’ on-page. I made this a primary inclusion criterion of my literary survey, unless there was a reasonable rationale behind non-usage of the term. The remaining twelve novels in my corpus have such justifications. Four of these twelve instances (33 per cent) appear in works of historical fantasy that omit the term ‘asexual’ as the time setting of the work predates its common usage. But in seven others (58 per cent), the word ‘asexual’ is absent because of a worldbuilding detail, with the term not existing in the fantastical lexicon of the fictional world. An additional one instance (8 per cent) substitutes the term ‘asexual’ for an equivalent word specific to the setting, but for the same reasoning as the previous; that is, that the term does not exist in this immersive fictional setting. I find this to be a perplexing omission considering that other terms from the real world can be imported without question – for instance, words used to describe gender, animals, and body parts. It is my belief that terms describing sexuality can – and should – be imported into fantasy narratives just as readily. With these justifications in mind, it should be noted that in all twelve of these instances, the characters’ asexuality is inarguable even without being explicitly named. These characters verbalise their absence of sexual attraction either through narration or dialogue, and often their absence of attraction is a driving force of the narrative journey, character arc, or both of these things combined.

The forty-two novels of my corpus contain forty-five asexual characters, with the mismatch between these figures occurring as there are multiple asexual characters in some of the novels under consideration. In some cases, these ‘extra’ asexual characters are in supporting roles to the asexual lead. For example, in Alice Oseman’s Loveless (Reference Oseman2020), aromantic asexual protagonist Georgia meets two other asexual people over the course of her journey to self-acceptance, both of whom help her to overcome her internalised negative beliefs about her sexual and romantic orientations. In others, there are two asexual main characters who steer the narrative side by side. In Calista Lynne’s We Awaken (Reference Lynne2016), Victoria first learns of asexuality when she enters a romantic partnership with asexual deuteragonist Ashlinn. Victoria quickly realises she is also asexual, and the two girls go on to renegotiate their boundaries with their shared orientation in mind. Three of the asexual characters in this corpus – Katherine from the Dread Nation duology by Justina Ireland, and Nadin and Isaak from Lyssa Chiavari’s Iamos series – appear in more than one novel. In these cases, I have tabled novel-specific information for each instance but have only counted character-specific data once. As an example, Katherine appears in both Dread Nation (Reference Ireland2018) and its sequel Deathless Divide (2020). Rather than table Katherine twice, I have included her character information just once, with the justification that these instances of asexual character are in fact the same character. In other words, it would be disingenuous to make character-specific claims when this data is skewed by duplicate entries, something I have taken pains to sidestep wherever possible.

3.2 Genre Breakdown and Exile Permutations

Assessing Asexual Exile as a complete picture means assessing each trope cumulatively, rather than in isolation. The Death-Adjacent Ace trope, for instance, can be found in six of the forty-two novels (14 per cent) under examination.Footnote 4 However, this statistic is hardly a fair representation of the broader problem at hand, given that the Death-Adjacent Ace trope is just one form of Asexual Exile. Examining Asexual Exile tropes broadly and across genre, then, is the only accurate means of making a proper assessment of its impact overall.

In literature, the term ‘genre’ broadly describes the styles and categories of works, grouped by common features such as storylines, settings, or character archetypes (Mays Reference Mays2019). As I have identified, Asexual Exile tropes loosely correspond with genre, with distinct qualities to match the works in which they appear (O’Connacht Reference O’Connacht2018). My literary survey corpus contains works of YA in the contemporary, science fiction, historical, and fantasy genres. To ensure my methodology is indeed clear, I will now provide a working definition for each of these genres, foregrounding my discussion of each genre’s typical Asexual Exile trope.

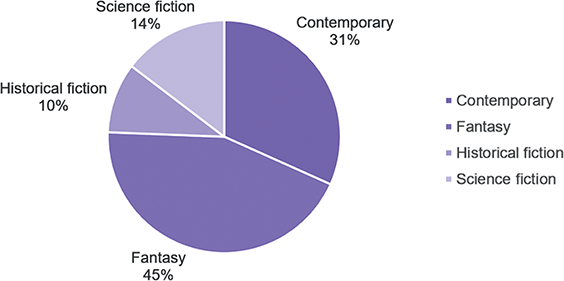

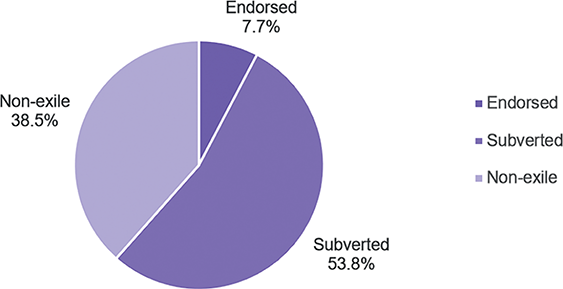

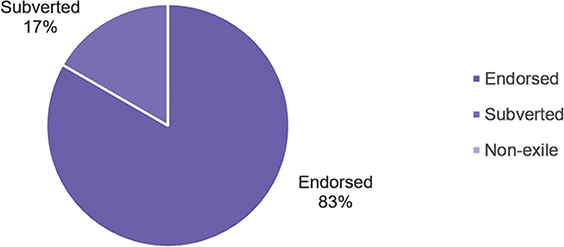

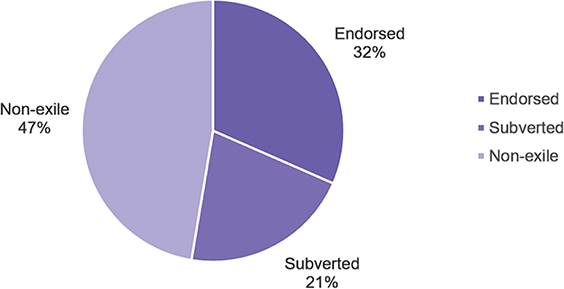

As stated, the forty-two novels within my corpus are a mixture of genres, including contemporary (thirteen), fantasy (nineteen), historical fiction (four), and science fiction (six) (see Figure 3). The fantasy genre is the most popular among these by far, accounting for 45 per cent of works studied, or almost half of works that met my inclusion criteria. This is an understandable commonality; fantasy, characterised by the impossible being made real (Clute and Grant Reference Clute and Grant1997), tends to be a prime target for queer representation since disbelief is already suspended. This makes this genre in particular a ‘safe space’ for characters who identify outside of cisgendered heteronormative expectations (Balay Reference Balay2012), more so than any other. That being said, it is encouraging that the next most popular genre for asexual representation is contemporary fiction, with thirteen instances accounting for 31 per cent of works studied. Contemporary fiction is known for its close resemblance to our real world, meaning no suspension of disbelief is required here to explain away the presence of asexual characters.

Figure 3 Genre breakdown of corpus

It is in this intersection of genres that we discover another point complicating the issue. When analysing Asexual Exile tropes, it is important to remember that while these genre-based distinctions are common, they are not unanimous. There are several cross-genre trope appearances, most commonly surrounding the Loner Ace contemporary genre trope, which appears in fantasy, science fiction, and historical fantasy genres as well. There is clear value in interrogating these tropes as they occur typically to genre, but it is apparent that these genre-defying instances must still be interrogated to properly understand the true saturation of Asexual Exile tropes overall. For this reason, I will go on to provide commentary not just on the frequency of genre-typical tropes – such as the Death-Adjacent Ace trope which is typical of fantasy, and the Loner Ace trope which is typical of contemporary – but of the broader rates of Asexual Exile for each genre, regardless of variant.

In the typical narratives of these exiles, three things tend to happen to asexual characters, regardless of the specific exile trope being employed. Characters either (1) are Exiled Alone, cast out of society in isolation, (2) are Exiled Together, with a significant other joining them in that exile, or (3) refuse to be exiled and instead remain a part of society in an Exile Refutation. These different permutations are analogous to the two major outcomes of exile representations, being that they either go endorsed without question as a narrative conclusion, or they go subverted, with exile instead a narrative complication for the protagonist to overcome. It is common for the latter representations to reclaim Asexual Exile tropes by directly centring characters who heal from their exile. These characters return to society and forge meaningful relationships, solidifying their place in our world.

3.3 Contemporary Genre and Loner Ace

Contemporary literature is best understood as a somewhat ephemeral means of describing recent writing ‘in our particular contemporary moment’ (Martin Reference Martin2017:20); ergo, what was contemporary in the 1800s is considered classical literature now. The contemporary fiction of the modern day most closely resembles what we might call ‘chick lit’: reflecting real life, grounded in realism, most commonly overlapping with romance (Cahill Reference Cahill and Reynolds2020). In my research, the contemporary genre refers to works which explore realistic portrayals of everyday life and adolescent experience, showcasing for young readers ways of ‘exploring their own identities and of discovering their place in the contemporary world’ (Knickerbocker, Brueggeman and Rycik Reference Knickerbocker, Brueggeman and Rycik2012:5; emphasis omitted).

The contemporary genre is a largely positive space for asexual representation, with the vast majority of exile storylines ending in an Exile Refutation (see Table 1 and Figure 4). Eight of the thirteen (62 per cent) constitute largely refuted depictions of the Loner Ace trope, with the remaining five of the thirteen (38 per cent) containing no exile tropes. Of the eight instances of the Loner Ace trope, only one of these is an endorsed instance of the Exiled Together permutation, with the remaining seven being Exile Refutation narratives.

Table 1 Exile in contemporary genre corpus

| Loner Ace | Other exile | Non-exile | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endorsed | 1 | 0 | N/A | 1 |

| Subverted | 7 | 0 | N/A | 7 |

| Non-exile | N/A | N/A | 5 | 5 |

| 8 | 0 | 5 | 13 |

Figure 4 Exile in contemporary genre corpus